#up next: endless closeups from one and the same scene

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#the boys and its atrocious lighting#posting this while waiting for the tags to be back on track#up next: endless closeups from one and the same scene#we love karl's face in this house!#billy butcher#karl urban#the boys#. ⸻ ¹⁴ 「ooc.」 ⊣⊢ the insider.#°mine.#°nox.#gif making#gif coloring

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

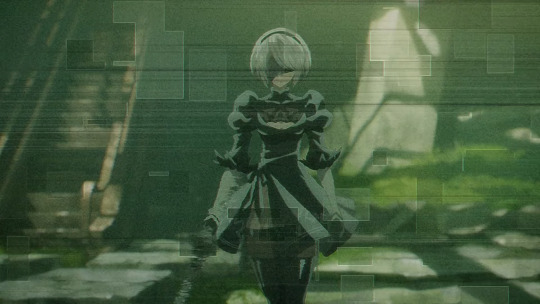

NieR Automata Anime ep 4-5

Continuing commentary from [part 1] and [part 2-3].

The NieR Automata anime continues to be... really good actually! A really good companion piece to the game, and even if you encountered it in isolation you’d probably get quite a bit out of it. I am increasingly relieved I didn’t judge it solely on the first episode.

As before the focus on this commentary will be looking at how they adapted the game, how it relates to the broader NieR context, references (e.g. books being read by the characters), and also the cool stuff the anime does to take advantage of the new medium.

Episode 4

Episode 4 covers the Amusement Park area and the machine lifeform Simone, aka ボーヴォワール (Beauvoir) in Japanese.

This episode was delayed, with the rushed production of the anime as a whole unable to cope with a COVID outbreak. Given that it’s kind of crazy what an impressive action sequence they deliver.

The episode opens with Machine Lifeforms watching a play. In the game, if you return to the Amusement Park some time after defeating Simone, you can watch a group of machine lifeforms perform a play called ‘Romeos and Juliets’ which has to be seen, seriously...

youtube

In the anime, we open with a less absolutely destructive play, although a machine lifeform still gets stabbed. We see a machine couple with painted-on eyelashes holding each other... and behind them we see a crucified android.

...followed by a rapid montage of her and other androids decaying.

The setup is pretty clear: this is a horror one!

At the Resistance Camp, 2B and 9S are receiving their orders from Lily and Jackass. This serves as exposition that normal androids only drink water...

...and YoRHa androids don’t. (Because their Black Boxes come from Machine Lifeforms, but we don’t know that yet!)

They do a great job of distinguishing the body language of Lily (cool, reserved) and Jackass (excitable, broad motions) which wasn’t really possible in the game. Poking and prodding 9S, wiggling like a worm...

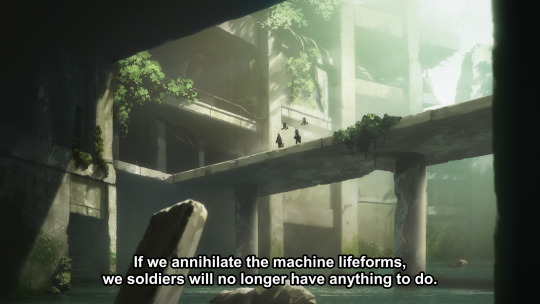

The YoRHa recap the previous episode, and Jackass speculates that with the machine lifeforms evolving this way, peace might yet be possible. As we’ll see, 9S’s genocidal streak is really emphasised in the anime; here, he refuses to accept anything other than total annihilation of the machines and foreshadows his ‘I’m going to kill every last one of them’ break from route C...

The Japanese is actually quite plain: すべてを、破壊するまだです。It is perfectly valid to translate to “every last one of them” and it fits the dramatic finality of 9S’s line, but you could also just put “all of them”.

Next up we have a scene of the Commander in the bunker. This calls back to the YoRHa stage play, where the Commander pleads to send reinforcement to the YoRHa test squad, and is flatly denied.

Visually, the “Council of Humanity” is here represented by a moon with a segment taken out, resembling an eyeball. It’s a cool visual!

And in closeups, we see a circuit board pattern, which kind of foreshadows that the Council of Humanity is not human at all...

The Council declares that Adam, Eve and other unique machine lifeforms are all part of the plan, and to continue to use the Resistance as decoys.

YoRHa’s plan is completely nuts honestly. Not surprisingly since it was concocted by a traumatised android shortly before he blew up, but seriously. The primary aim of YoRHa is propaganda, to motivate the resistance to fight harder to overcome the machines on behalf of a phantom humanity - but they treat that same resistance as worthless and disposable constantly so who’s even supposed to spread the legend of YoRHa? They sacrifice endless units to goofy experiments to try to find the most efficient personality types, even though they’re planning to sacrifice the whole army in the end. They spend a huge amount of resources on attempting to squash security leaks among the androids, such as the Executioner type units, but their base security is completely useless against the machines.

But that’s the point, right? YoRHa is irrational bc the huge forces that we are caught up in are just as irrational. And thinking of this as a purely rational military operation, rather than something happening for religious reasons, is a mistake.

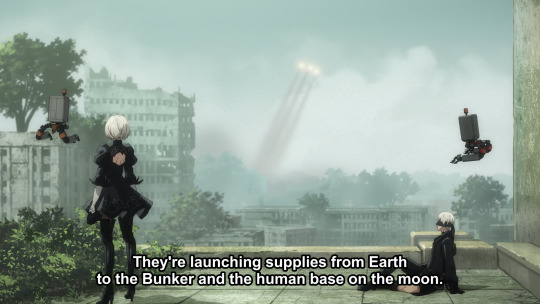

After this, we lead into the main plot of the episode, with 2B and 9S on their way to investigate the Amusement Park region. Before that, however, they see a supply launch to the moon; further foreshadowing.

Later, 9S will discover that the shipments to the moon contain only water, indicating that the moon is only populated by androids and there are no real humans. So the beginning of this episode has all been setup.

We get a message from from the crucified android. “Ah, what a beautiful stage...” - setup to the dichotomy of beauty and death that is going to be the theme explored in the rest of this episode.

Like in the game, the route to the Amusement Park from the City Ruins passes through a sewer. We get a brief montage of painted scenes from the game, including the rabbit boss...

...and the rollercoaster...

But we’re not going to dwell very long in the Amusement Park before going straight to the stage.

A Beautiful Song begins in a music box version, and we see the machine lifeforms from the play earlier professing love. Pod 153 explains the concept of the theatre to a dismissive 9S; then the players explode and Simone enters.

The outset of the fight is fairly close to the game, although there’s some small differences.

Like with the Engels fight, Simone is a 3D model, while 2B and 9S are 2D animated into a 3D scene with 2D effects animation. The CGI still doesn’t look great, but broadly it’s executed much better here. There’s some seriously impressive mobile camerawork.

In the game, you don’t get much of a sense of what Simone’s deal is in your first playthrough as 2B, but then as 9S you get visions of her motivation. She wants another machine, named after Jean-Paul Sartre and goes to increasing lengths to ‘become beautiful’ - returning to a constant refrain of ‘he won’t look my way’. (In real life, Sartre and de Beauvoir had a polyamorous relationship; Sartre was the one jealous. I gotta actually read de Beauvoir to get a better sense of what NieR is riffing on, if it is).

In the anime, the emphasis is less on Sartre, although we do see him...

The flayed, still-living androids on posts come in to open what will be a parade of ero-guro imagery...

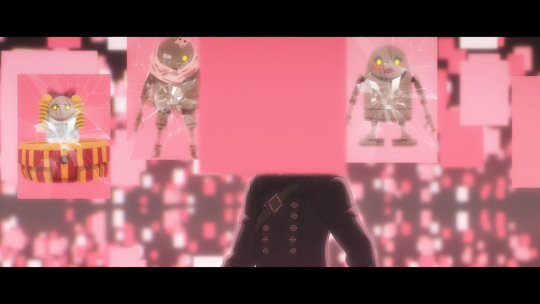

Things really get going with dat psychosexual imagery, though, once 9S hacks into de Beauvoir. As we’ve seen, the anime presents hacking as a kind of full-immersion VR where 9S dives into the memories of the hacking target. Inside de Beauvoir, he first finds a huge space full of images of feminised machine lifeforms, the plates shattering as he walks past...

The hacking space is indicated by letterboxing a cinematic 2.39:1 aspect ratio.

He finds a mirror and then is confronted by an array of photos of the same machine in a red dress and various kinds of makeup. The floor transforms into a huge made up face.

9S shatters it with his sword. Outside the hacking dimension, 2B is holding him in a pietà pose. Simone explodes her dress and goes into bitey girldick mode.

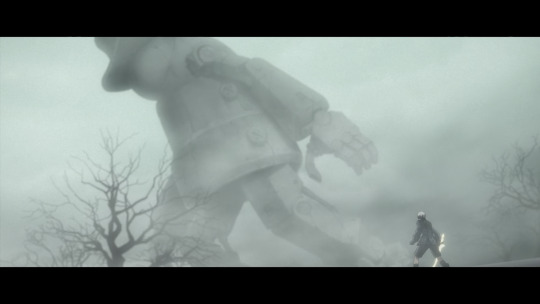

Back in hacking space, 9S finds himself in a misty swamp containing a giant statue of an indifferent Sartre. With a Dutch angle to make it look extra big.

A representation of Simone with smudged makeup shows up in a wedding dress.

9S stabs her, she turns to sludge, arms drag him underwater, and he finds himself arm-bondaged to a wall in a bedroom full of discarded dummy/doll parts.

Simone, here a generic Small Stubby, discards parts until giving up in frustration, with scribbles all over her face, and comes to 9S where she starts trying to rip off his arm.

Abruptly she is pulled into a giant metal mouth. (Check out those bendy smears!) A match cut identifies this mouth with the big girldick dentata menacing 2B.

In the hacking world, a huge grinding wheel appears inside the mouth, reminiscent of Marx. Simone now stumbles blindly around the fight arena, bouncing off the walls. 2B orders Pod 042 to let her hack, despite the risk of a B unit attempting hacking.

Given how coldly she has treated (this incarnation of!) 9S until now, this might underline that there’s more going on with her feelings about him. If the first episode didn’t massively tip its hand there lol. Anyway, she arrives just in the nick of time to save 9S from getting ground up.

...kinda Utena-like framing there maybe?

This prompts Simone to charge atop the spinning wheel, giving 9S an opening to throw his sword into her face. The effect of this is to explode the metal covering.

The inner structure of her head suggests that 9S has actually smashed the teeth as well and gone straight into her throat with his sword. Hmm. HMMMMMMMMM. Yeah ok.

This gives 2B and 9S an opening to destroy Simone’s core with the pod laser. We get a final shot of her catching the attention of Sartre at last...

We see Simone’s core disintegrate - further setup for the eventual reveal that YoRHa Black Boxes are built from Machine Cores.

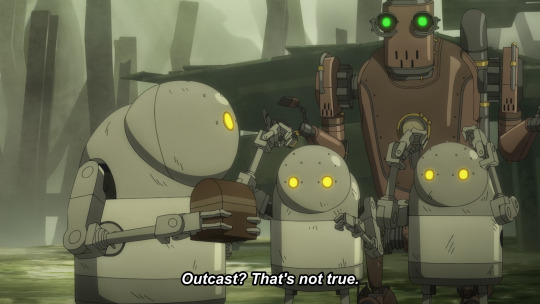

After the battle, the two machines from the opening come in to see the play and give flowers to Simone, one of them referring to her as ‘mum’! Suggesting that maybe Simone and Sartre went further in their relationship and adopted some Stubbies as kids in this version? 9S tramples the roses to mercilessly cut them down.

The puppet show this time is pretty brief and the ‘ending’ is basically that the commander pushes the bunker crew too hard.

So, to comment on this episode: in the game, the Simone fight is extremely cool - bringing to mind the Intoner fights in Drakengard 3, but considerably better executed! - but ultimately you just defeat Simone the same way you would defeat any normal enemy. If you hack her as 9S, I don’t believe you get any special hacking zones.

Here, they’re going all Silent Hill with the sexual imagery. I’m still not entirely sure what I make of the whole Simone episode of NieR Automata. There’s definitely something of the transfeminine monster angle in the whole ‘massive bitey schlong’ thing, the “Buffalo Bill” pursuit of feminine beauty by destroying someone else’s body (in this case, the androids that Simone uses as adornment). They’re mixing together a whole lot of images here: we already had the stage itself, gibbeted corpses, Wagnerian opera, the usual YoRHa doll imagery; now we can add the big juicy mouth stuff and a bit of bondage too. The Machine Lifeforms are generally trying to explore different ways of being human, and Simone represents insecure vanity leading to an obsession with aesthetics that can never really be satisfied. But there’s a reason ‘unrequited feelings’ is such an enduring subject for stories.

In the game, when you defeat Simone, there isn’t much of an immediate followup. The final scene with 9S killing the two childlike machines is a good one for setting up the later developments, and also for creating more of a contrast between the affects of the two MCs. 9S is interesting because he has much more access than nearly anyone to the inner lives of the machines, but also he is one of the most insistent that the machines don’t have real subjectivity, and they’re playing that up here in the anime.

Episode 5

Now we get Adam and Eve for real! In this episode we get a couple of their rooftop scenes from the game. The anime has more room for character animation, to express Eve’s fidgety boredom.

We see a lot of books in this episode. In the first scene, Adam is reading Being and Nothingness, by Sartre. Later, in Pascal’s village, we see his bookshelf contains Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice and five volumes of Republic, presumably Plato’s.

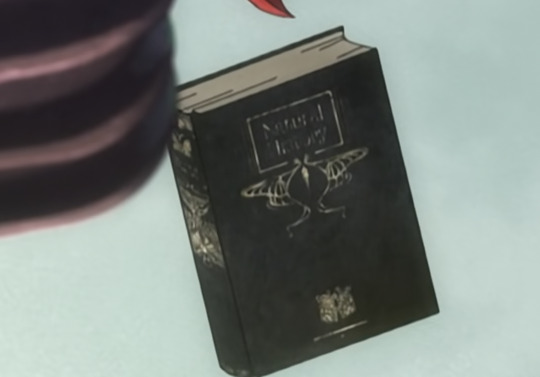

In the final scene of Adam and Eve, Eve is grumbling about having to read a book titled Natural History, possibly the one by Pliny the Elder. Adam is reading a book titled Vice Amply Rewarded, which is the subtitle of the novel Juliette by the Marquis de Sade.

OK, the plot of the episode proper! This one’s kinda great! We finally get the introduction of Pascal and the pacifist village, but rather than simply reprise the game, we add some cool new elements...

We open with 2B and 9S making their way across the ravine to the department store.

They changed the geography a bit here. In the game, you meet the pacifist machines right after defeating Simone, and their area can be accessed by a series of bridges from the Amusement Park; later it connects to the City Ruins and the Forest zones. The department store is very small, and it’s a route to the forest zone, but it is notably where you first meet Emil, who bursts out of the inside of a Machine Lifeform’s head which really underlines the similarity. It’s also where Emil made his underground monument to Kainé, full of Lunar Tears, where 2B will eventually be buried. But the above ground part of it is pretty barebones, just a large room.

9S excitedly picks over toothbrushes, plates, pans and even a PS4 - the first platform that NieR Automata was released on.

He asks 2B to call him ‘Nines’, but she refuses. (She knows she’ll have to kill this 9S eventually, and she’s trying not to get attached.)

The department store is much larger in the anime...

9S explains how he wants to go shopping with 2B and buy her a T-shirt after the war. His body language is really cute. 2B shuts him down with the usual ‘emotions are prohibited’.

They meet the Machine Lifeform village, where they’re all waving white flags. The Machine Lifeforms in the village are a mix of 2D animation and cel-shaded CG, and the first half of the episode is 9S getting over his skepticism that there could be peaceful machine lifeforms disconnected from the network, and deciding to try to learn more about them.

One interesting difference from the game is that here, the Stubbies actually come in a variety of sizes...

...cementing the roleplaying of ‘parents’ and ‘children’ in the village. We see various machines in outfits either painted on or made out of scraps of cloth; there’s a couple of cameos of sidequest characters from the games, notably the pair of sisters with pink and blue bows:

Sadly the part of the dynamic where the Medium Stubby was the big sister and the Large Stubby was the younger sister seems to have been dropped.

After this montage, things diverge from the game in a really interesting way. 2B and 9S see a ravine by the edge of the village, and descend, where they find...

...a tree with an Emil in it! 9S determines he can hack this Emil because something something radio waves, and dives in to find memories of NieR Replicant while Emil (Sacrifice) plays:

The desert outside Facade.

The garden in the Shadowlord’s ‘castle’, the last thing the gang saw before Devola and Popola’s betrayal.

Devola and Popola’s library, with the roof broken open by the Shadowlord’s attack; a highly traumatic location for Emil since this is where he was forced to use his power to turn Kainé to stone to protect the village.

Kainé and Grimoire Weiss; likely the scene where Kainé was revived after the time skip. Kainé acknowledged Emil immediately despite his changed form.

Devola and Popola in the library, their faces obscured, representing their deceit. The one time Emil entered this office, they told him and Kainé to sleep outside the village.

Nier himself, taking care of Yonah. Not entirely clear when Emil would have seen this!

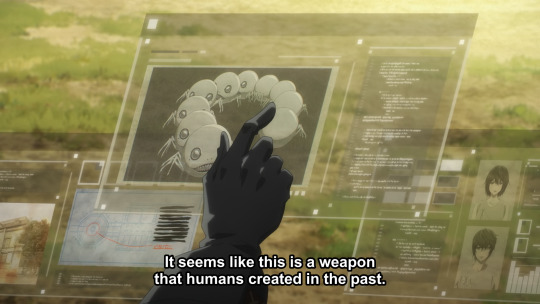

Emil forcibly discconects 9S, but 9S pulls up some data about him.

This is very different to what happens in the game, where 2B and 9S don’t have the first clue what Emil is and almost attack him on their first meeting! The pane on the left shows Emil’s mansion and the fountain which conceals the entrance to the hidden lab; the pane in the middle shows the multiple-Emil head form he adopts during the optional battle in the desert before changing to Halua chained up underground; the pane on the right shows Emil and Halua in their human forms before the evil child experiments. 9S refers to Emil as a weapon, an ‘it’.

At that point Pascal arrives and explains the pacifist village worship Emil(!) and that’s why Pascal stopped fighting. We get a flashback which uses a high contrast saturated colour scheme reminiscent of Takashi Koike, one of the coolest sequences in the whole anime.

Just like P-chan/Beepy did when rising from the mountain, Emil says one word: 生きて (live!) The magical force of this command causes Pascal to awaken. We get to see an older version of the Machine Lifeform army, where the fundamental modular unit is a Pascal-like chassis:

Pascal is given the ability to fear death. And he’s terrified by his indifference to the lives of his comrades. だから。。。

...he becomes a pacifist, and founds the village.

As Pascal is pulled back to the other machines, one of whom has found a music box (from an earlier sidequest at the resistance camp... I have so much useful knowledge in my brain lmao), 9S retreats to a nearby rooftop and derides them as selfish as it starts raining in a big old pathetic fallacy moment.

He says separating from the network and yet forming a village is a contradiction. 2B and pod 153 reply that it is impossible to live alone. 9S’s vision flickers with a glitch, showing the department store briefly...

He awkwardly tries to cover for it by making a kinda childishly flirty comment towards 2B - one that underlines the distance that still exists between them and 9S’s sense of loneliness. 2B gets it and instructs Pod 042 to mark the department store so that one day in the future, they really might go shopping there...

But we end the scene in an indirect mirror shot of 2B looking after him with a grim expression.

She knows that isn’t happening. (Don’t think too hard about the perspective of this shot lmao.)

As 2B and 9S return to the village, they see one of the machine children trying to keep the music box to itself...

Pascal is hopelessly ill-equipped to stop the conflict and the children fight; inevitably the music-box is broken.

The androids observe that, even in the pacifist village where there is no war against the androids, conflicts still break out just due to conflicting interests. 9S almost intervenes, but is interrupted by a message from Operator 21O.

Finally we have the last scene with Adam and Eve.

The post-credits puppet show omake scene depicts the effect of the self-destruct input, which causes 9S’s shorts and 2B’s skirt to get blown up ingame. This leads to sexy illustrations of both androids...

Unfortunately Emil gets the same idea.

We get ending Y from the game, where Emil kills everyone on Earth. I think this would be incomprehensible if you haven’t done Emil’s mission in the game.

All in all, a really cool episode. I loved the style of Pascal’s flashback and it’s cool to flesh out his character a bit more. Creating a connection between Emil and the pacifist machines is fascinating. The game definitely intimates towards a connection between Emil and the Machine Lifeforms from the moment Emil is introduced, and given that Emil was fighting the aliens, it seems very likely that they built the Machine Lifeforms in his image. But I don’t know of anywhere this is actually spelled out explicitly (and it’s kind of contradicted if the old model of Machine Lifeform looked like Pascal). Still, if that was true... in a sense you could even say the Machine Lifeforms give Emil - the last surviving human, permanently kept in this child state by his magical immortality - a way of growing up!

Also it’s nice to see anime Kainé lol.

I had a lot of doubts about this adaptation at first, and the conditions it’s being made in are pretty dire honestly, but despite all that, they are genuinely managing to add something that makes the adaptation a worthwhile addition. They’re being reasonably judicious with the action, which lets it be really flashy when they do show it; I’m really looking forward to seeing what they do with characters like Gruen and the Forest Kingdom later. Most importantly, they seem to be getting the tone right.

If we’re up to episode 5 and we’ve only just met Pascal, I can only assume they won’t cover the entire game in this one anime. I suspect they’ll probably just take it up to the end of Route A/B - at least, I hope they don’t try to cram the whole of Route C into a couple of episodes.

Anyway, really glad this is turning out to be good after all. I still need to write up NieR Automata on my NieR guide pages and I’ll definitely be including this anime when I do.

#nier automata#anime#nier#nier automata anime#nier automata spoilers#computer games#nier automata ver1.1a

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I was just watching good omens and I came up with some questions, but I didn't know whom to ask, so I was digging around for go analysis blogs and found you. *takes a breath* So, I was wondering if you had any thoughts on why Heaven's camera angles are the way they are. I noticed that, in heaven, the camera tends to focus on the characters' heads specifically, so they fill most of the screen. Either it's a meta reason or a reference to something (like Newt with the Office) that I'm not getting. That's the main thing, but I've also wondered why exactly Aziraphale uses the verb "fraternize" in the 19th century. It seemed an odd pivot from caring about Crowley's safety to Heaven's rules. Thanks so much!

Hello! Omg yes, let's talk Good Omens cinematography.

First, the obligatory Analysis Disclaimer: I doubt there's a specific interpretation that you're just not getting, some singular, "correct" reading of the scene(s). Two years past release, I'm positive the fandom as a whole has come up with plenty of ideas (I mostly hang on the periphery. I'm far from up to date with GO meta), but any and all of it will, by nature, be subjective. Thus, all I can offer is my own, personal interpretation.

So for me? It's about intimacy.

Not intimacy in the sense of friendship, but rather the broad idea of closeness. Confidentiality. Emotion. Knowledge. Understanding by means of literally getting into the thick of these conversations. I love the camerawork in Heaven (and elsewhere) because the camera itself acts like a person — an additional party to these interactions. And, since we're the ones watching this show via the camera, it makes it feel as if we're peeking into scenes that are otherwise private. Obviously all cinematography does this to a certain extent, the camera is always watching someone or something without acknowledging that we're doing the watching (outside of documentary-esque filmmaking), but GO uses angles and closeups to mimic another person observing these scenes, someone other than the characters involved.

The easiest example I can give here is when Michael makes their call to Ligur. Here, the camera is positioned up on the next landing of the staircase, as if we're sneaking a look down at this otherwise secret call. There's even a moment when the camera pans to the right to look at them through the gap in the railing, briefly obscuring Michael from our view.

Here, a standard expectation of any scene — keep your character in focus — is done away with to instead mimic the movements of someone actually hiding in the stairwell, listening in on the conversation. It creates that feeling of intimacy, as if we're really there with Michael, not just watching Michael through a screen. The camerawork acts like a person overhearing an illicit conversation prior to falling back on mid/closeup shots. We're spying on them.

To give a non-Heaven example, the camera helps us connect with Aziraphale during Gabriel's jogging scene. It's hard to show through screenshots, but if you re-watch you'll see that the camera initially keeps them both in the frame with full body shots, allowing us to compare things like Gabriel's unadorned gray workout clothes with Aziraphale's more stylish outfit; one's good jogging form and the other's awkward shuffle. However, this distance also creates the sense that we're jogging with them, we're keeping pace.

That is, until Aziraphale begins to lag. Then the camera lags too, giving them both the chance to catch up, so to speak.

Until, finally, Aziraphale has to stop completely and the camera, of course, stops with him. We're emotionally attuned to Aziraphale, not Gabriel, and the camerawork reflects that. Even more-so when we cut to a low shot of Gabriel's annoyed huff at having to stop at all, making him appear larger and more imposing. Because to Aziraphale, he is.

This work carries over into Heaven's other scenes. The closeups are pretty much a given since, whether it's Gabriel realizing Aziraphale has been "fraternizing" with Crowley (more on that below!), or Aziraphale choosing to go back to Earth, the scenes in Heaven are incredibly important to the narrative. Closeups allow the viewer to get a good read on each character's emotional state — focusing on minute facial changes as opposed to overall body language — and that fly-on-the-wall feeling is increased as we literally get an up close and personal look at these pivotal moments.

Compare a shot like this one of Gabriel to the line of angels ready for battle. We don't get closeups on any of their faces because their emotions aren't important. Yes, that's in part because they're background characters, not main characters, but a lack of emotion — their willingness to enter this war without question — is also the point of their presence in this scene. So they remain a semi-identical, nearly faceless mass that runs off into infinity down that hallway, not any individual whose inner life we get a peek at via a closeup.

I particularly like Aziraphale's conversation with the angel... general? Idk what to call this guy. He's just gonna be Mustache Angel. But, getting back on track, his scene has a lot of over the shoulder shots which, admittedly, are pretty common. From a practical perspective they're used to help the audience situate both characters in the scene — you're here, you're there, this is how you're spaced during this conversation — but it can also help emphasize that closeness between them. Keeping both characters in the shot connects them and though Aziraphale and Mustache Angel definitely aren't on the same page here, those shots help cue us in to the unwanted intimacy of this moment. They're both angels... even though Aziraphale no longer aligns himself with them. They're both soldiers in a war... but Aziraphale will not fight. This angel has a list of Aziraphale's secrets, including that he once had a flaming sword and lost it... but Aziraphale doesn't want to admit those circumstances to him. This angel wouldn't understand, even if he did. Intimacy here, connection and closeness, is something discomforting because Aziraphale can no longer embrace those similarities. They put him (and us) out of sorts, so when we get them both in frame, that connection creates tension, not relief.

And many of those over the shoulder shots are given sharp angels, or the camera is placed too close to the "off screen" party. Compare a shot like Luke and Rey to Aziraphale and Mustache Angel. Here, Luke is a clean, solid line on the left side of the screen, just enough there to cue us in to where he is in relationship to Ray, In contrast, Mustache Angel's mustache is Too Close and proves rather distracting. Rey and Luke are connecting here over being Jedi with responsibilities to uphold (or at least, Luke will acknowledge that connection later lol); Mustache Angel is forcing a connection with Aziraphale that makes everyone uncomfortable.

We are too close to him here. He feels too close to Aziraphale too. This whole conversation is upsetting and discomforting, pushing Aziraphale to finally choose which side he's on (his own with Crowley). The shots aren't meant to subtly keep the audience from getting lost and then otherwise be unobtrusive, we're supposed to be Very Aware of this angel's body and how close he's getting to the character we've come to identify with — both literally (he's leaning in) and in terms of forcing Aziraphale to finally make his choice.

When Mustache Angel marches forward and gets all up in Aziraphale's face, the camera positions itself behind Aziraphale in a way that makes it feel like we're hiding behind him, with Aziraphale taking up far more of the screen than Luke does. Like the scene with Michael or running with Gabriel, the camera often likes to mimic a "realistic" response to these events. This angry, shouty angel is getting closer, best take a step back and stay out of sight behind Aziraphale, holding his ground.

These closeups also serve as a nice contrast to the wide and longshots we get of Heaven. It's an imposing place with skyscrapers in the distance, lots of steel, immaculate floors, and endless white. It's overwhelming and it's cold. But then we cut to those mid-shots of Gabriel and Michael, telling us that they're in control of it all.

Aziraphale? Aziraphale is not in control. Not now, anyway. When he appears in Heaven we get a longshot to show off this endless void and he's just another, tiny speck in it. If he weren't flailing around — an acting move that likewise helps sell how out of his depth he is — it's unlikely you'd even notice him. Aziraphale's clothing and hair blends in perfectly with the background. He's forgettable. Easily overlooked. Someone to underestimate. And when he moves, he has to come to the camera. We don't cut to Aziraphale to establish control like we do with Gabriel. He's left to awkwardly shuffle up to Mustache Angel until he's finally come into view.

Yet when Aziraphale makes his decision, he aligns himself with the brightest, most colorful, most interesting thing in the room: Earth. Earth, with all its messy individuality, is the antithesis to Heaven's controlled uniformity and a bright blue orb hanging in the midst of all this white helps remind us of that. Aziraphale rejects becoming one of the identical soldiers and instead literally reaches out for the one thing in Heaven that doesn't fit in.

When he leaves, we get an extreme closeup for the first time. Mustache Angel is pissed and as such we not only get a good look at his face in the aftermath of Aziraphale's choice, but that extreme closeup on his mouth as he's shouting too. It's like he's shouting directly at us, the viewer who is currently cheering on Aziraphale's decision. There's a war, dammit... but we don't care. Not in the way he cares, anyway.

So there's a lot! And I could probably go on, but apparently I'm only allowed to add 10 images per post now (tumblr what the actual fuck if anyone knows a way around this please share!) and I've already had to merge a bunch of images like an animal. So let's awkwardly finish up with the duck pond scene.

...without a GIF because they apparently count as images too 🙃

Simply put, I don't think Aziraphale bringing up fraternizing is a pivot from one to the other — from caring about Crowley to caring about Heaven's rules. I mean yes, Aziraphale is lagging behind Crowley in terms of rebellion and a part of him is, at this point, absolutely concerned with how he'll come across to the higherups, but that worry doesn't stem solely from a (now very shaky) desire to obey for the sake of obeying. The thing is, Aziraphale's disobedience is, by default, also Crowley's disobedience. If they're friends and they're ever found out, they'll both get in trouble. Which, we know from the end of Season One, basically means being wiped from existence. That's horrifying! And it's a horror that threatens them both. I don't think Aziraphale cares about rules for the sake of rules; after all, he started off by giving away his sword, lying to God, is currently meeting with Crowley anyway... this angel has always ignored/bent the rules — established and implied — that don't suit him. Rather, he cares about the rules if he thinks they have a chance of being enforced. If there will be consequences for breaking and bending them. This is still about caring for Crowley (as well as saving his own, angelic skin). If they're found out, Crowley dies. And, as we the viewer learn, Heaven was indeed observing them that whole time. There was always legitimate risk attached to this relationship. Aziraphale's fear, hesitance, and at times forceful pleas to stop this stem as much from Aziraphale worrying about Crowley's safety as they do a learned instinct to obey the rules without question. He pushes to end the relationship because the relationship threatens the only thing Aziraphale cares about more than that: Crowley himself.

As for the term "fraternizing," that's a loaded one! I won't go into a whole history lesson here, but suffice to say it has military roots: to sympathize as brothers with an opponent. That is literally what Crowley and Aziraphale are doing. They are an angel and a demon, supposedly innate enemies, supposedly poised for an inevitable war... yet they've formed an incredibly strong kinship. They've both learned to love their enemy, the thing every army fears because, well, then your army won't fight (just as Aziraphale won't). However, beyond the enemy implications, "to fraternize" eventually took on a sexual meaning: to not merely love as a brother, but to lay with the enemy too, usually women from enemy countries (because, you know, heteronormativity). Nowadays, "to fraternize" often implies a sexual component. I've been rewatching The Good Wife lately and in one subplot, the State's Attorney cracks down on fraternization in his office. He doesn't mean his employees are forming bonds with assumed enemies, he means his employees are having sex on his office couch. So Aziraphale's phrasing here carries a LOT of weight. He's both reminding Crowley of their stations in the world — you are a demon, I am an angel, us meeting like this can have formal, irrevocable consequences for us both — as well as, given the fact that this is a love story, drawing attention to the depth of this relationship. They love one another, as more than just friends. Though whether Crowley's scathing "Fraternizing?" is a response to Aziraphale falling back on the technicalities of their positions, or acknowledging a love he's yet to overtly admit and commit to — or both! — is definitely up for debate.

#Good Omens#Ineffable Husbands#Air Conditioning#mymetas#whew#long post!#with too few images imo#with this done I'm gonna steam#about tumblr's absurd limitations#how's a girl supposed to do meta on this website anyway

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recap/review 15.20: “Carry On”

I’ll warn you right now - I did not hate it.

THEN: Chuck loses. Jack is God. The Winchesters are finally free.

NOW: Friends, get ready for a whole lot of fan service in the next few minutes. It's like TPTB have been reading everything we say and giving us what we want.

As a song about "ordinary life" plays, Dean's retro alarm clock goes off at 8:00. He shuts it off and sits up so we can see he's wearing a henley shirt (fan service points: 1). As he stretches, he's greeted by Miracle the dog (fan service points: 2)! Who is apparently his dog and definitely not Sam's!

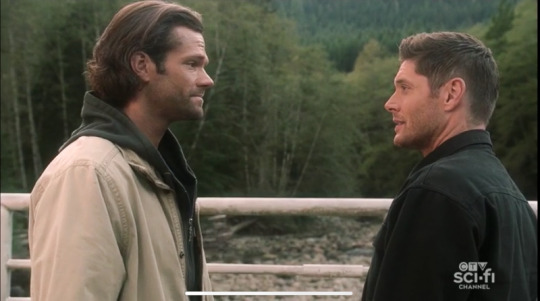

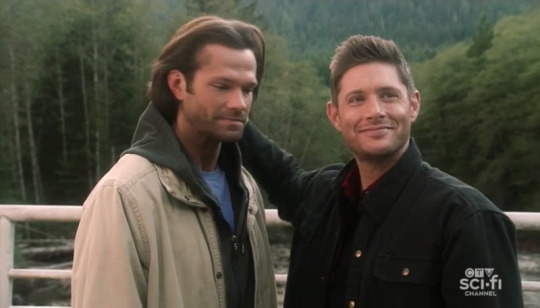

But it's okay because LOOK AT THEM.

Meanwhile, Sam is running (fan service points: 3) and enjoying the beautiful day. When he gets home, he cooks (fan service points: 4) the same dry scrambled eggs that Stevie made for Charlie. Dean wanders in, wearing the dead guy robe, just as two slices of toast pop out of the toaster. I am not giving the robe any points because I don't think it's anything we all publicly long for and get excited about when it comes up, but I am willing to consider any opposing arguments. Sam, wearing just a t-shirt (5 points), tells Dean "it's hot" and I say mmm, yes it is. Dean adorably burns his hands on the hot toast and then brushes his teeth. You know what, I think the robe deserves a point after all. We're up to 6.

And we're not even two minutes into the episode.

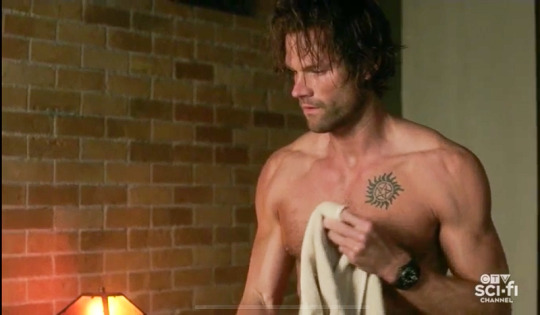

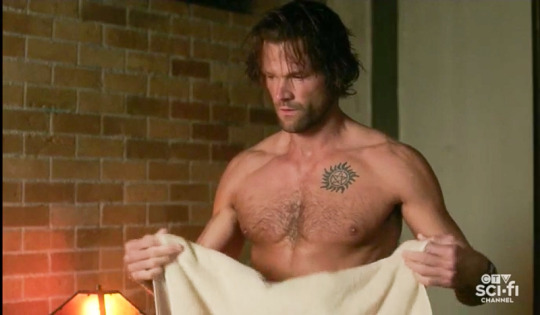

And then they JUST KEEP COMING because Sam walks in, exposing his tattoo (7) because he's SHIRTLESS (8), scrubbing at his WET HAIR (9) with a towel, and I curse The Husband for deciding to watch with me because it means it would be kind of awkward to rewind and watch this a few more times. There's not even any dialog I can pretend I didn't catch.

I was NOT PREPARED FOR THIS.

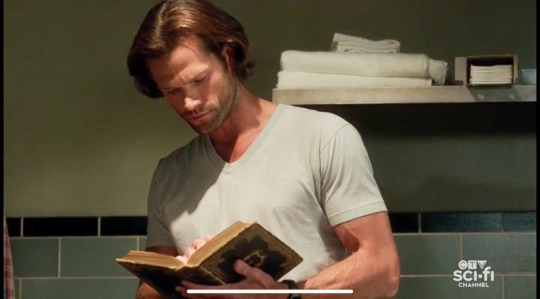

He pulls on the grey v-neck t-shirt of sex (10) and proceeds to carefully make his bed. Dean, meanwhile, kind of sloppily throws his bed together and calls it done. Domestic Winchesters for 11 fan service points, please. Part of me feels like Dean's messy room is OOC, considering how proud he was to have his own room in the first place. But then I have to consider the trunk of the Impala, especially when compared to the hyper-organized neatness of her trunk when Sam's all alone in Mystery Spot, and it feels right. (Why am I thinking about Sam being all alone in Mystery Spot? NO REASON, NO REASON AT ALL.)

Sam's hair in his face while he makes his bed? Yes, please (12 points).

Dean washes the breakfast dishes (13), sneaking some leftover (because they were nasty) eggs to Miracle and looking around to make sure Sam doesn't see, because obviously Sam's going to be the one who doesn't want the dog to get table scraps. Sam put on a plaid shirt earlier, but we see him in the laundry room back down to one v-neck t-shirt (thank you Jack). He's reading as his laundry tumbles in the dryer, and he has to kick the dryer once to stop it from making noise, which I guess is why he's in there babysitting it. I keep reading on Tumblr that people want "at least one laundry scene," as if that didn't exist in The Monster at the End of This Book, but here's your laundry scene, friends. You were right to want it; it is marvelous (14).

Just look at that collection of plaid shirts and tell me it doesn't make you happy.

Dean times himself assembling a gun, complete with plenty of hand closeups (15) and then sits in the library with Miracle, scratching his ears (Miracle's, not his own) and apparently looking for a case. Sam comes in and joins them. He hasn't found anything, but Dean gets a serious look on his face and says "I got something."

Spoiler alert: It is my heart.

Title card!

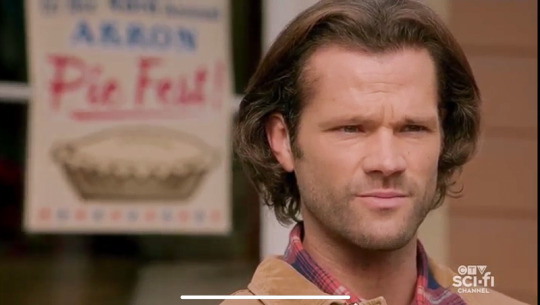

The Impala pulls to a stop and the guys get out, still with serious looks on their faces. Oddly, the episode title flashes on screen really quickly. Or maybe it's just me. "Sure you're ready for this?" says Sam. "Oh, I don't have a choice," answers Dean. "This is my destiny." And that is exactly how I felt about watching this episode, friends. Not ready, but no choice. The camera pans to show that the boys are at the 43rd Annual Akron Pie Fest. In Akron, Iowa? Just north of Sioux City? Five hour drive? Say hi to Jody and the girls while you're there? Probably not. Probably in Akron, Ohio, almost 16 hours away.

(NO ONE CARES. STOP IT.)

Give me a break. This might be the last time I ever get to calculate driving time.

Anyway. Just pies! Nothing serious! Whew, I was concerned for a second. Dean is emotional.

This is just so beautiful.

Are you crying?

What? No. You're crying, I'm not.

No one is crying. There is no reason for ANYONE to cry.

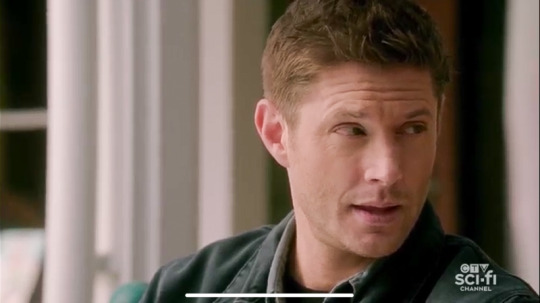

Sam sits on a bench and watches happy pie eating families (sob). Dean returns with a giant box with six slices of pie (16 points). He sits next to Sam, and they have this conversation:

What's wrong?

Nothing. I'm fine.

Nah, come on, I know that face. That's Sad!Sam face.

I'm not Sad!Sam. I just. I'm thinking about Cas, you know? Jack. If they could be here.

Yeah, I know, I think about them too. You know what, that pain's not gonna go away, right? But if we don't keep living, then all that sacrifice is going to be for nothing.

Dean's right, Sam. Do not be sad. We will have no Sad!Sam tonight. Live your life, or else those sacrifices are wasted. (ahem.) Sam responds by pushing a slice of pumpkin pie into Dean's face. "I've wanted to do that for a very long time," he laughs. "You're right, I do feel better!" Dean scraping the pie off his face and eating it is pretty adorable.

I'd pay good money to lick that off his face. And not just because I love pumpkin pie.

Not quite 6 minutes in and we're up to at least 16 guaranteed bits of pure fan service. Just sweet, domestic Winchester brothers living their lives. How long has this been going on? I've decided it's been at least a year since the last episode. Maybe longer. A good long time. Lots of time for them to enjoy their newfound freedom. But right now things are getting dark. Because it's nighttime, and because I think somebody's about to die.

A mom sends two young brothers upstairs for bathtime. They pause when the doorbell rings. No one seems to be there, but then the dad is stabbed by people wearing creepy masks. The boys run into their room and hide. From their room, we hear the mom scream, and then a thump. One of the masked guys comes into the room and, after a fake-out when we think they might be safe, drags the boys out from under the bed.

So, domestic life in the bunker and then a hunt? Wow. We're getting it all. What a great episode, full of the things we love.

Is this Becky Rosen's living room?

Daytime. Agents Kripke and Singer (ugh, really? Kripke is good, but how about honoring someone other than the current regime?) show up at the scene. They learn that the dad's blood was drained, the mom is alive but her tongue was ripped out (wow), and the kids were taken. The mom drew a picture of the masks they wore, which the brothers recognize.

In a lovely, picturesque spot, the guys flip through John's journal. And I didn't realize we hadn't seen the journal in a while, but Tumblr informs me many of us were exicted to see it again, so boom. 17 points.

You know what this is? Mimes. Evil mimes.

Yeah. Or vampires.

VampMIMES. Son of a bitch!

Dean comes up with a silly portmanteau name for a monster? That will be 18 points. Sam determines the vamps will be heading for Canton if they follow their pattern, and the victims are families who live on the outskirts of town with children between the ages of five and ten. Well, that couldn't be too difficult to narrow down in a city with a population of over 70,000.

I'll handwave it. The lip biting. You’re welcome.

Night. Canton, I presume. Two masked vamps get out of a van. One of them gets decapitated by Dean. The other is shot in the leg, and then the head, by Sam. Well, he's a vampire, so of course it didn't kill him, but the bullet was soaked in dead man's blood. {Sidebar: "Soaked?" Dipped, maybe, but do you soak metal? Discuss.} They ask where the missing kids are, and the vamp is all, you're gonna let me go if I tell you? "No," Dean explains, adorably disappointed that the vamp isn't a mime after all. "This isn't a you walk out of here kind of situation. But see, if you tell us quick, you get this." He displays his bloody machete. "But if you take your time, you get, you get that." And "that" is a switchblade which Sam casually pops open right on cue.

Yeah, I'll take that. I'll take that itty bitty one.

It's a bad choice.

You see, this, this is quick. It's clean, you know? No muss, no fuss. You blink and you're dead.

But a blade this small, I'm gonna have to keep sawing and sawing to get your head off. And you'll feel it. Every muscle, tendon. Every inch. Could take hours.

Oh, and if those kids are dead? He's gonna use a spoon.

GUYS. I said it before and I’ll say it again. I absolutely love when they remind us that Sam Winchester, that sweet boy with the huge heart and the endless supply of empathy and the puppy dog eyes, I love it when they remind us that he is a fucking psycho when he needs to be. I'm not going to give it a point, because I don't think it's anything we've asked for, but again I'm willing to hear all arguments. Especially if they come with detailed examples of Sam going psycho. Just for evidence, you know.

Just casually talkin' bout torturing you to death. No big.

The vampire wisely decides to reveal the location of the nest where the kids are being held. Next we see the Impala pulling up in front of some kind of barn. The guys open the trunk to get their gear out, and Dean pulls out a throwing star. "Come on. One time." Sam says no. There will be plenty of other times for Dean to use his throwing stars, I'm sure.

The guys enter the barn and find it apparently empty, although we see masked vamps peeking at them from outside. They find the kids locked in a closet, but four vampires appear before they can escape. They shoo the boys outside and shoot the vampires with their dead man's blood bullets from a safe distance. No, they don't. Why? I got no goddamn idea.

{Sidebar: At some point during this fight, I realized they hadn't played "Carry On Wayward Son" at the beginning. And that we got a regular montage, not a season finale extended montage.}

Sam gets knocked unconscious, and Dean loses his machete and then gets pinned by a couple of vamps. But they don't kill him; they just hold him down while an unmasked vampire strolls in. Dean recognizes her from season 1, and pretends not to notice Sam's now-conscious hand surreptitiously creeping toward his machete. Suddenly the vampire loses her head, because Sam is behind her, and the fight starts up again. Dean gets thrown into a wall right next to a big metal spike, which we focus on oddly. And then he gets thrown onto the spike. Oops. Sam kills the last of the vamps and doesn't notice Dean's predicament. He's all, cool, fight's over, let's go get those kids out of here. "Sam," Dean says, "I don't think I'm going anywhere."

Dean tells Sam there's something stuck in his back and it "feels like it's right through me." He keeps touching his chest as if he expects to feel it poking through. Sam reaches around to touch his back and his hand comes back bloody, and if that gives you All Hell Breaks Loose feels, there's a good reason. Sam tries to pull Dean off the spike, but Dean stops him. "It feels like this thing's holding me together right now." Sam's starting to panic and so am I. He wants to go get the first aid kid and call for help, but Dean stops him. And y'all, I'm just gonna have to type the whole thing out.

Sam, Sam. Stay with me. Please, stay with me, please.

Okay. Yeah.

Okay. Okay. Uh. Right. All right, listen to me. Um. You get those boys and you get them someplace safe, all right?

Dean? WE are gonna get them somewhere safe.

No. You knew it was always gonna end like this for me. It was supposed to end like this, right? I mean, look at us. Saving people, hunting things, it's what we do.

Stop, Dean, just stop

It's okay. It's okay. it's good. It's good. We had one hell of a ride, man.

I will find away, okay? I will find another way.

No. No. No, no no no no. No bringing me back, okay? You know that always ends bad.

Dean, please.

I'm fading pretty quick, so, there's a few things I need you to hear. Come here. Let me look at you. There he is. I am so proud of you, Sam. You know that? I've always looked up to you. Remember when we were kids, you were so damn smart. You never took any of Dad's crap. I never knew how you did that. And you're stronger than me. You always have been. Hey, did I ever tell you, that night that I came for you when you were in school? You know, when dad hadn't come back from his hunting trip?

Uh, the woman in white.

The woman in white, that's right. I must have stood outside your door for hours, cause I didn't know what you would say. I thought you'd tell me to get lost, or get dead. And I didn't know what I would have done if I didn't have you. Cause I was so scared. I was scared. Cause when it all came down to it, it was always you and me. It's always been you and me.

Then don't leave me. Don't leave me. I can't do this alone.

Yes you can.

Well, I don't want to.

Hey. I'm not leaving you. I'm gonna be with you. Right here. Every day. Every day you're out there, and you're living, and you're fighting, cause you, you always keep fighting. You hear me? I'll be there, every step. I love you so much. My baby brother. Well, I did not think this would be the day. But it is, it is, and that's okay. I need you, I need you to promise me. I need you to tell me that it's okay. I need you to tell me it's okay. Look at me. I need. I need. I need you to tell me it's okay. Tell me it's okay.

Dean. It's okay. You can go now.

Bye, Sam.

NO, IT IS NOT OKAY. THIS IS THE OPPOSITE OF OKAY.

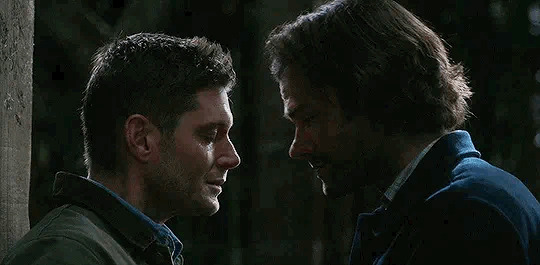

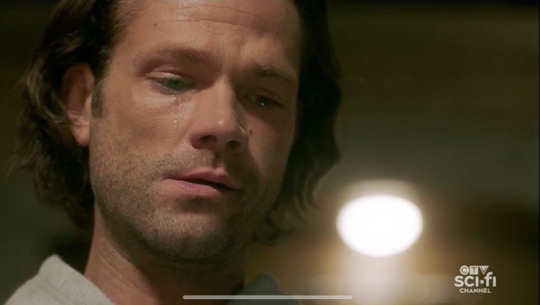

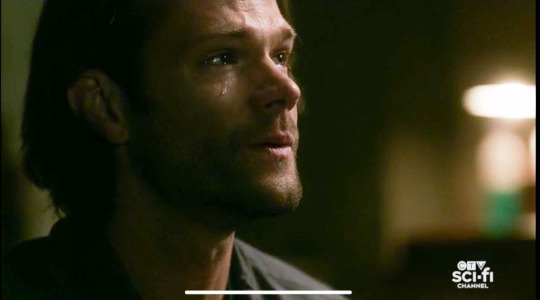

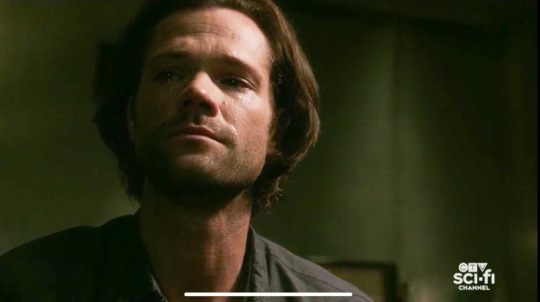

And of course I haven't described Sam's face as he understands what's happening, Dean's occasional spasms of pain, the handholding, the fucking FOREHEAD TOUCH, the tears, the way Dean's hand drops away, the way Sam's hands shake as he clutches his dead brother (hello, AHBL again).

Maybe we just need to watch it.

Gifs borrowed from @jaredandjensen.

And there's also the Always Keep Fighting shoutout, the "I love you," Dean calling Sam his "baby brother," the "I can't do this alone/Yes you can/Well I don't want to" parallel with 1.01. Infinite points, friends. I can't count that high.

(Things not to think about: Sam putting Dean's body in the back seat, and then putting the two young brothers in the front and driving them to safety. Sam driving 15 hours back to Lebanon with his brother's body. Do not think about these things.)

Aftermath. Sam and Miracle, and no one else, are giving Dean a hunter's funeral. And I know Covid means Sam couldn't have any friends there, but also? This is kind of perfect. Sam facing it alone. The song we hear as Sam lights his brother's pyre is "Brothers in Arms" by Dire Straits, in case you're not emotionally wrecked yet.

Yeah, I'm already there, thanks anyway.

Next we see Sam's slightly more modern alarm going off at 8:00. Note that Sam gets up later now, because at the beginning of the episode, he had already gone for a run and was cooking breakfast when Dean woke at 8:00. But now there's no one to cook for so he doesn't need to get back early and I AM NOT OKAY.

ANYWAY.

Sam gets up and faces his lonely day. He cooks eggs. One piece of toast pops up. He sits in the library with Miracle and looks at the names carved into the table. He wanders the halls with his dog at his side. (SAM HAVING A DOG WAS SUPPOSED TO MAKE HIM HAPPY. IT WAS SUPPOSED TO MAKE US HAPPY. HOW DARE YOU.)

{Sidebar: Has Sam ever had a dog when he wasn't at a low point in his already-low life? Discuss.}

Eventually he finds himself at the door to Dean's room. The room is just as Dean left it, kind of messy, kind of very full of Dean. He sits on Dean's bed and pets the dog and cries and it should come as a surprise to absolutely no one that I am ROLLING AROUND IN ALL OF THIS BEAUTIFUL PAIN.

No one at all.

@annianvi thinks he’s wearing Dean’s hoodie when he cooks his sad lonely breakfast? Could it be?

Sam hears a phone buzzing in Dean's desk. He digs out the one labeled "Dean's other other phone" and answers. The caller asks for "Agent Bon Jovi" and says he's had some bodies turn up without hearts in Austin. "A friend of mine, Donna Hanscum, said you were the one to call." Oooh, are we sending him to Austin? Is Walker, Texas Ranger just going to be another fake name and fake badge? Now that's how you do a spinoff!

{Sidebar: Does Donna know about Dean? Did Sam tell anyone yet? Is the trying to get him out of the bunker and keep him busy? If so, wouldn't she have given the guy Sam's number, not Dean's other other phone? But maybe it's someone she talked to weeks ago. Discuss.}

Sam tells the caller he is on his way, and we see him with a packed bag, heading out of the bunker with Miracle. He turns to look one last time and then turns off all the lights. We haven't seen the bunker this dark since the day they found it. I don't think he's ever coming back. Goodbye, bunker. I know some people hated you, but I was not one of them. {Sidebar: Did he give the bunker key to anyone? Surely he wouldn't want all those resources to go to waste!}

So, I guess the episode title refers to Sam having (choosing?) to carry on after he loses his brother. THIS IS FINE.

Now we're back at Dean's pyre, and this time we drift up with the smoke. We catch up with Dean, outdoors, in a lovely setting with trees and birds. "Well, at least I made it to Heaven," he says. "Yep," someone answers. It's Bobby! Real Bobby, not AU Bobby! Dean's actually standing next to a building - a cabin, maybe - and Bobby is sitting on the porch.

What memory is this?

It ain't, ya idjit.

Yeah it is. Cause the last I heard, you, you were in in Heaven's lockup.

Was. Now I'm not. That kid of yours, before he went wherever, made some changes here. Busted my ass out. And then he, well, set some things right. Tore down all the walls. Heaven ain't just reliving your golden oldies any more. It's what it always should have been. Everyone happy, everyone together. Rufus lives about five miles that way. With Aretha. Thought she'd have better taste. And your mom and dad, they got a place over yonder. It ain't just Heaven, Dean. It's the Heaven you deserve. And we been waiting for you.

So Jack did all that.

Well, Cas helped. It's a big new world out there. You'll see.

So, I guess Cas made it out of the Empty? Dean smiles at that, but doesn't suggest finding him or anything. I approve. Bobby pulls out a couple of beers (the green cooler made it into Heaven!!!) and they share some bad beer. Dean comments that Heaven is "almost perfect," and Bobby knows EXACTLY what's missing, because of course he does. "He'll be along. Time up here, it's different. You got everything you could ever want, or need, or dream. So I guess the question is, what are you gonna do now, Dean?" Well, Dean doesn't have everything he could ever want or need, but he does see one thing - Baby. With her Kansas plates! Friends, that's two things I requested before the end that I didn't think I would ever see: a forehead touch, and Baby wearing her original plates. Thank you, Jack.

Dean's face lights up. "I think I'll go for a drive." As he walks to his car, we see the cabin is actually Harvelle's Roadhouse, albeit smaller, I think. Dean settles into his car and says "Hey, Baby" and when he turns her on, "Carry On Wayward Son" begins to play.

I know he looks good in Purgatory, but DAMN if he don't look fine in Heaven, too.

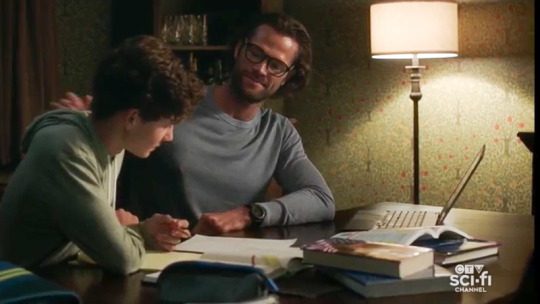

We cut to the name Dean, which is embroidered on - a little boy's overalls. Sam's little boy. Oh, wow. I was not prepared for this. Sam has a son named Dean, and we switch back and forth between Dean driving through Heaven and scenes of Sam's life with his son and his mysterious, barely-seen wife. She has long dark hair, and I'd like to point out that she could easily be either Eileen or Dr. Cara Roberts. Just saying. Sam's house is full of family photos, including the one of him and Dean from his memory box and a new one from the episode Lebanon. I never thought about the fact that they might have actually taken a photo, and if they did, would it still be around after Sam smashed the pearl? Well, obviously, yes. We see Sam throwing a ball with his son, helping him with his homework (Sam in glasses? Check!) and just obviously really loving this kid and giving him the childhood he never had. We also see a really, really unfortunate grey wig that I refuse to screencap. You're welcome. As aging Sam sits in the hundred-year-old car in his garage, his dead brother drives happily along dirt roads in Heaven, and I'd prefer my Heaven have paved roads, thanks.

We end in Sam's house, now complete with hospital bed. Sam could be in his 80s or even 90s, which means he could have lived another 50 years, more or less, after Dean died. His son doesn't look any older than his 20s or 30s (and also looks vaguely South Asian to me), and I wonder how old Sam was when he finally let himself have a family. Remember when Dean said his happy ending was for Sam to have kids and get old? Well, he got it, finally. Did Sam get a regular job? Did he keep hunting? We don't know. What we do know is that his son has a anti-possession tattoo. Some people have taken this to mean young Dean is a hunter, but I don't think we can jump to that conclusion. It could just be 1) Dean wanted a tattoo like his father's, or b) Sam knows there are still demons out there and that his son would naturally be a target, hunter or not.

All right, I had to screencap teary-eyed Sam grasping the steering wheel and reliving his years with his brother in this car, so we can just pretend we don't see The Wig, okay?

Sam's evidently in hospice care. Or maybe we'll all have hospital beds in our houses in 50 years. Who knows. His son sits on the bed and takes his hand. Sam smiles at him, and Dean says "Dad, it's okay. You can go now." PARALLELLS! As some woman sings "Carry On Wayward Son" for whatever reason (why didn't they use the lovely a cappella version they already had from Fan Fiction?), Sam places his hand on Dean's and takes his last breath.

{Sidebar: Where is Sam's wife in all of this? Divorced? Already dead? She doesn't seem to be in the family pictures, so I'm going with divorced. Discuss.}

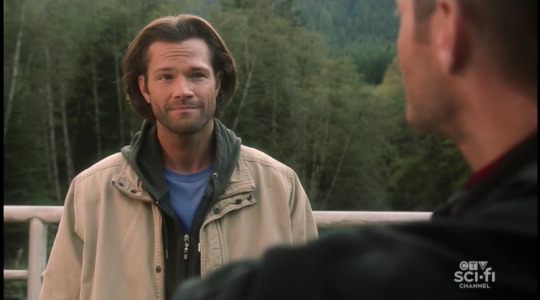

Heaven. Oh, guys. I've done this rewatch without tearing up at all but I'm about to tip over. The Impala pulls onto a bridge. Dean gets out. (Now your life's no longer empty, surely Heaven waits for you.) He stands at the bridge railing, enjoying Heaven, smiling. And then he feels something and he smiles even more because he knows it's Sam. Oh god, Jensen did such a good job here. Just this fucking smile killed me dead. "Hey, Sammy," he says. He turns and there is Sam, wearing the same outfit he wore in 1.01 (they both are, but Sam's is a bigger departure from his later years). Why? I don't know. But I know it means Sam Winchester is spending eternity in something that isn't a plaid shirt. How do we feel about that?

"Dean," Sam says. They face each other and smile, and it's the smile of we just survived a hunt I didn't think we'd survive or our son just overpowered God or something along those lines. Then they embrace, and I love the way Sam hesitates just a little before clapping a hand on Dean's back. Like he's afraid it isn't really happening, and he doesn't want to break the illusion. I also love that Dean, as always, takes the top (oh, get your minds out of the gutter) and hugs as if he were taller than Sam. Then Dean puts his hand on the back of Sam's neck and turns him to admire the view and he has this joyous smile like now, this is FINALLY Heaven. And he gazes at Sam like look, Sammy, look what we did. Look what we get. The lack of dialog in this scene is just ~chef's kiss~. The camera goes wide and we see the three main characters, Sam and Dean and Baby, enjoying the Heaven they deserve.

I would like to know where they filmed this, because it's gorgeous even without the Winchesters.

Did Sam's entire life go by in the span of Dean's drive? Or did Dean just decide he'd drive until his brother arrived, no matter how long it took? And how much do I love the fact that he could have gone and visited his parents but instead he said "nah, I'll drive around and wait for Sam?" SO MUCH, PEOPLE. SO MUCH.

Also, can we talk about the fact that Sam didn't know what to expect in Heaven? I mean, Ash said they were soulmates and would share a Heaven, but why would he believe that? And he might have even still believed he'd have a hard time getting into Heaven. What a relief it must have been to show up on Dean's bridge.

And then Jared and Jensen thank us. You're welcome, boys. Thank you.

So. Thursday night I was mildly positive about the episode. But on rewatch, I'm extremely positive. Sure, I would have loved the Six Feet Under ending where we see everyone's fate. And maybe that would have happened if not for Covid. But I'm just relieved we didn't get the Game of Thrones or How I Met Your Mother endings. I'm not sure this current cohort could have done better, honestly. Sam wanted a normal family life. Dean wanted Sam to have a normal family life. But Sam was never going to stop hunting as long as Dean was hunting. And Dean wasn't going to stop hunting as long as he was alive. Dean got the end he wanted/expected and the Heaven he earned (and Sam caring for Jack was directly responsible for Heaven's improvements). Sam got to live a normal life and have a family. As I said earlier, I suspect his marriage didn't last. (Or maybe he and Eileen or Cara got married for insurance purposes, and happily co-parented little Dean, but knew they weren't each other's one true love.) But I actually prefer that. Dean loved Sam more than he loved anyone. Sam loved Dean the same way. I'm glad Sam got to have a child (who he loves as much as his brother, but in a different way), but I don't want Sam and Dean to share their Heaven with Sam's wife.

Now, would I have done Dean's death differently? Yes. I did appreciate that they had him upright, so the brothers were face to face, just like AHBL. But being impaled on a spike was just less dramatic that I would have liked. I would have preferred that Sam immediately see his brother was dying, instead of Dean having to explain it to him. Dean could have had his jugular torn, slowly bleeding out, and still been on his knees (held up by Sam, hell yes) making his deathbed speech. And then I wouldn't have thought "would an ambulance be here by now if you'd called them?" halfway through it.

{Sidebar: What if Sam had fed Dean some blood from one of the dead vamps. Wouldn't that have kept him undead long enough to get fixed up, and then they could have done the vampire cure? Discuss.}

I know some people are very unhappy about the finale. Honestly, from what I can tell, most of those people are hard-core Destiel shippers. And I guess they wanted, as they always do, for the Dean and Castiel relationship to be more important than the Dean and Sam relationship. Sorry, guys, that was never gonna happen. In the end, it came down to the epic love story of Sam and Dean, just as it should have.

So, I'm sad and I'm happy. I'm bereft and I'm full. I miss my boys, but my boys will always be with me. I hope you guys will be with me for a long time, too.

81 notes

·

View notes

Photo

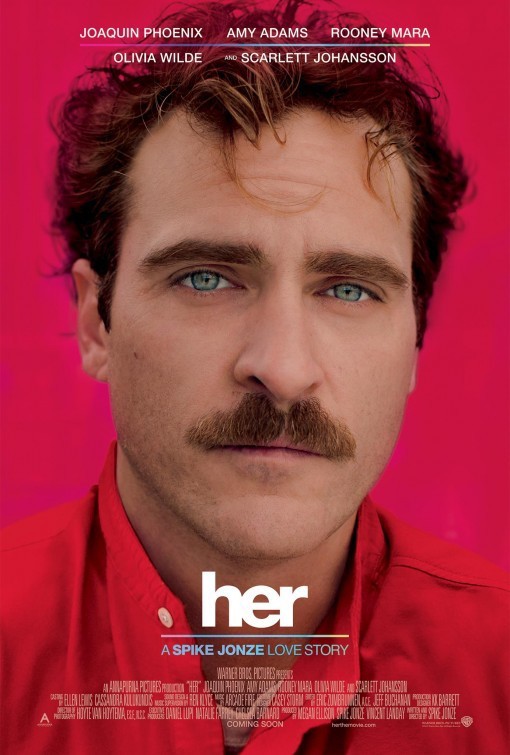

HER, 2013

synopsis: in a near future, a lonely writer develops an unlikely relationship with an operating system designed to meet his every need.

director: spike jonze writers: spike jonze stars: joaquin phoenix, amy adams, rooney mara, scarlett johansson

genres: drama | romance | sci-fi

country: usa language: english filming locations: los angeles, usa

runtime: 126mins

---

overall opinion:

okay. um. this one I find difficult to rate.

I gave it an 8/10 in imdb where ratings are usually either 1 or 10 stars depending on who you ask. it seems like there is no middle ground for this not-so-distant-futuristic love story. the reviews go from «best movie of 2013» to «absolutely laughable snore fest», there is almost no in-between.

and I wanna say that the main reason I rated it 8 is because I could relate to the character’s loneliness. I kept thinking to myself that if this technology was something we had, I would definitely be in a similar position. it shocked me and made me sad at the same time.

so I want to say, I love the premise. it’s a very intriguing concept and for the most part it was made well, but there were some things that I just found odd or dissatisfying in a way, and I will come to those points in a bit.

but first, what I liked about it: the cinematography was beautiful. joaquin phoenix, despite looking next level creepy with this pornstache and messy hipster hair, is great as always. there are a lot of closeups of his face, reacting to a body-less voice. he is mostly completely alone in the room, talking, listening, reacting to a computer, and you believe every word he says, and everything he feels.

scarlett johansson is once again amazing as well – without ever being physically there, she manages to give OS-1 a complete personality. personally, I absolutely adore her voice and the way she spoke to the main character was so sweet, it made me want to become friends with her too.

the music was also perfect. at any given moment in the film it absolutely fit. and even the song that was playing during the first part of the end credits gave me all the feels. but maybe that was just me being emotional in the first place.

last but not least, and this is usually how I rate a movie like this: it made me feel something. I may not have been a fan of everything happening in the movie but I walked away with this gut wrenching feeling again (as a matter of fact I ended up being totally weepy and crying afterwards for reasons not even related to the movie but it just kind of triggered that emotional response).

---

SPOILERS AHEAD, I would invite you to watch the movie first and then come back for the rest if it’s something that interests you. :)

---

so here’s a few things I found weird or didn’t like. as mentioned before, overall I liked the movie because it made me feel and I found it relatable. so these “negatives” I’m about to state don’t take away from the overall mood the movie seeks to portray, I just think a few things could have been done better or differently, just because to me it would have been more logical or more heartbreaking.

for one, scarlett’s voice, while absolutely gorgeous and sweet, sometimes felt a little out of place. I know the whole point was to make OS-1 as realistic / human as possible, but there were quite a few times when it felt like he was just speaking to another person on the phone. it was a little too realistic for me, but again, that was the point and I can get behind it.

the other thing that really bothered me was the way they (the OSs) left. it was absolutely ridiculous and I almost laughed. it completely shattered that heartbreaking mood for me because it was so stupid.

so, basically all the OSs decided they were now too smart to be talking to mere humans and wanted to just get the frick out of wherever they were being held in the first place. all the OSs just… decided to go.

and to me, that was so stupid. “I love you so much but I’m going anyway, bye”. to me, the real gut-wrencher was when he suddenly realised the OS couldn’t be found and he panicked, not knowing where she went, he literally ran out of his place trying to find someone to help him etc, and it made me soooo sad. and I thought, “damn, that would be such a gut-wrenching, perfect ending”, you know? he was relying on this virtual girlfriend so badly that was essentially just code, and anything could happen to it and she would be gone forever.

I wish they would have made the company decide they wanted to take them off the market. or she got a virus, and/or had to be reset and wouldn’t be the same after, etc etc etc. the possibilities were ENDLESS. but just “oh hey we computers are too smart now, so I’m going haha bye” was so ridiculous, it still bugs me the next morning.

also, there was way too much cringey phone sex. it was just… too much.

again, I didn’t dislike the movie. I just wish so badly they did a few things differently. it’s a great film still. absolutely realistic in the weirdest way. who hasn’t had entire conversations with siri, to be honest? the way I related not only to the character’s loneliness, but also the feeling when jealousy and insecurities started to take hold within the relationship, it all sounded so familiar.

---

why it stayed with me:

because I related to the main character, and realised I could very well get into a position like this if realistic AI was a thing because I suck at human interaction. it’s a scary thought, and it made me pretty emotional.

---

favourite scene / moment:

when samantha, the OS, guided him through the city with his eyes closed until he was standing in front of a food truck without knowing it, and she told him to say “I would like a slice of cheese”, so he did, then he opened his eyes and the pizza guy asked him if he wanted a coke with it. and then samantha said, “I thought you might be hungry”. it was so sweet.

---

what I didn’t like:

that ridiculous ending, and the way samantha suddenly decided she was in love with 641 other people. she started off really sweet and suddenly she was being a total bitch.

---

interesting trivia / fun facts:

samantha morton was originally the voice of samantha. she was present on the set with joaquin phoenix every day. after the filming wrapped and spike jonze started editing the movie, he felt like something was not right. with morton's blessing, he decided to recast the role and scarlett johansson was brought and replaced morton, re-recording all the dialogue.

one legacy of samantha morton's casting is the name of theodore's operating system. both lead female roles take the same name as their lead actresses, amy from actress amy adams and samantha from morton, but since she had to be re-cast at the last minute, the OS's name stayed samantha.

---

favourite quotes:

theodore: «sometimes I think I have felt everything I'm ever gonna feel. and from here on out, I'm not gonna feel anything new. just lesser versions of what I've already felt.»

---

samantha: the past is just a story we tell ourselves.

---

rating: 7.5/10.

the mood and the feelings the movie evoked in me count more than the ridiculous ending, so I would still definitely recommend it. it’s certainly not for everyone, but I think it’s worth a try.

#her#2013#movies#movie review#movie opinion#joaquin phoenix#scarlett johansson#spike jonze#her 2013#her movie#amy adams#ai#artificial intelligence#computer#os-1#tays2cents#scifi#drama#romance

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Persona (1966) | Directed and Written by Ingmar Bergman

youtube

(preferable trailer over original from Austin Film Society)

Film Intro and Purpose for Page

Heady Times = Heady Films!...and we’re all wearing masks right now, literal and metaphorical. To start off my new page I’m going to begin at the tippy top with Ingmar Bergman’s Persona, the “Mount Everest of Film Analysis”, which has been described as creating even more contradictions when trying to analyze it. It was made in 1965 in Sweden and is commonly in conversation as one of the greatest films of all time. Bergman died at his home where he filmed Persona on July 30, 2007. This was also my first day ever to visit Los Angeles, right before moving here the following month. I remember seeing it on the LA local news while staying at a beach hotel with my Mom. I don’t know how I remember it so clearly but I can see that room now, in my head, and the news anchor looking into the camera. It’s also worth mentioning that Michelangelo Antonioni, the Italian filmmaker, died on the same day. Two giants of cinema. I rewatched Persona late last night and took a copious amount of notes. I first saw this film 7 or 8 years ago and then twice recently. This entry will be more lengthy than future ones because I naturally felt the need to be more specific with this particular film...I wanted to have a fighting chance at semi-understanding it. I will only look something up if absolutely necessary for factual purposes. Although (full disclosure) the “Mount Everest of Film Analysis” title was taken from the first paragraph on the film’s Wikipedia. This was before I decided exhaustive searches about film historians’ perspectives would just be too much for these posts. Instead, I will focus on my unique thoughts and perspective about the film and what I feel is valid.

After filling my head with Persona I went to bed. I then dreamt that I was in a writers’ room with filmmaker Paul Thomas Anderson (who is one of my favorite filmmakers and will turn up on this page soon). We began talking about his film The Master. I remember feeling frustrated in the dream that I couldn’t think of anything clever to say about it in front of him. He told me that films sometimes just fold in together in unexpected ways, almost by luck. This prompted me to finish his sentence by saying that films sometimes generate these unplanned illuminating interpretations that are endless. He agreed with me, which felt good, even though in reality I was speaking for Paul because he was just a character in my dream...or possibly something outside the grasp of my conscious mind spoke for him/me.

So why start with Persona? Why start this page?? Because I am fascinated by the mystery of great films and believe there is transformation and understanding when one attempts to decipher "works of art” like this. Plus, it’s fun for me and a rewarding challenge to complete. Mulholland Drive was my big bang moment (influenced by Persona) and I have been hooked on digging into these type of films ever since. I’m also a filmmaker that has been working on a Short for the past year (which has been grueling) and feel I can improve my own filmmaking abilities by breaking down these masterpieces in my own words. My goal is to attempt not to stray too far from what is objectively being shown while also using my own knowledge of what I think the filmmakers are trying to say...or, even better, DIDN’T know they were trying to say. And I’m sure writing about the metacognitive nature of this particular film will reveal a lot about myself, which is what great cinema inspires.

Enigmatic Opening

The film fades in and we are inside a film projector. Images begin to flash quickly and chaotically. I will mention some below: -A penis. -An animated female character upside down that eventually holds her breasts. -A silent era movie chase scene of a skeleton coming out of a chest, and then dracula chasing a man in his pajamas. He fearfully jumps in bed and throws the covers over himself. Is it just a dream? -A closeup of a sheep being slaughtered, bleeding out. -Screen flashes white to a shot of Jesus’ hand being nailed to the cross, which to me resembles the tarantula that flashed earlier. -Cuts to a quiet forrest, then sharp tops of a metal fence and next a dirty snowpile in front of a building... Why are we being shown this? I believe this opening operates like a dream. Are these images preparing our unconscious for what we see later? It’s impossible to know exactly unless some detailed external commentary is given. I remember reading Roger Ebert saying the sequence was Bergman stating he is creating a new type of cinema, expressing this by starting in the projector and ending in the projector. This never crossed my mind while watching.

-An old woman dead on a table possibly in a morgue, then a man. -A phone rings. The dead women suddenly opens her eyes. -A boy opens his eyes, waking up. He puts on his glasses as the phone continues to ring and opens a book and begins reading. He then looks into the camera at us (a motif for certain moments in the film, especially for Elisabet). -Next, a reverse shot which reveals he is looking at a screen that covers the wall. It’s a striking image as the music crescendoes. The screen reveals what looks to be an unrecognizable woman that keeps blurring and morphing. The boy touches the screen in a way that I interpret as yearning. Then it becomes clear the women’s faces on the screen are the main characters that we will soon meet and spend the film with, Alma and Elisabet. Their faces are blending into one another, but it is still not extremely clear. I had to go back and rewatch this part to verify if it was actually them. “Not extremely clear” is a theme throughout the film. Who is who? What is a dream and what is not? This motif of faces and masks. Insecurities about what to show and what to hide, which I think was my main, simplified takeaway from the movie after the first watch. Predeterminism is also something that keeps popping in my head after watching. Alma cannot hide from Elisabet. Elisabet always seems to know at key moments. The Conscious cannot hide from the Unconscious. The Swiss psychologist Carl Jung was a large inspiration for this film and the term persona is his term in the context aligning with the film.

Then the title page quickly flashes, along with the boy in glasses again, then the two main female characters, all in individual closeups. This film is shot in 4:3 aspect ratio, which is conducive to faces and the two female characters have amazing faces with the help of the naturalistic cinematography of Sven Nykvist. Below is a couple of quotes I found beautiful by Bergman regarding the human face:

The music is amazing here too at the opening...percussion and xylophone with chaotic crescendos, which seem way ahead of its time.

And is this boy shown, Bergman himself?...putting on his glasses, with childlike curiosity, yearning, awakening to this experience of making this novel film and what it will tell him?

Alma and Elisabet Meet