Text

The continental United States in an alternate history where Andrew Jackson was never president. Jackson dies late during the 1828 campaign; John Quincy Adams wins a second term, which is fraught with difficulties, and is succeeded by Martin van Buren, who wins election in 1832 and 1836. The next twenty-five years proceed more or less as they did historically, including the rising sectional tensions over slavery, with some differences:

Most notably, the policy of Indian removal is not pursued against the "Five Civilized Tribes" in the American south. This angers many in the southern states who resent what they see as Adams' leveraging of federal power to protect the native nations, and a secondary goal of the Civil War will become driving them out of Confederate territory.

The Second Bank of the United States lasts a bit longer--its charter is renewed for another ten years in 1836--but is still defunct by the mid-1850s.

With no Trail of Tears the western part of the Arkansas Territory is not converted into the Indian Territory, and joins the Union with the rest of Arkansas in 1836.

The whole Minnesota territory is admitted as a single state in 1858.

During the Civil War, the native population of the South opposes secession, despite indifferent to the question of slavery; viewing them with suspicion, the Confederate army begins a campaign against them almost immediately after the war breaks out. As Union forces progress down the Mississippi River and into Georgia, they are supported by the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw in particular; meanwhile, a Fourth Seminole War breaks out in Florida. By the time the war concludes, de facto independent governments of Native Americans and freed slaves exist in northern Mississippi, southern Alabama, and central Georgia. Abraham Lincoln survives an attack by Confederate partisans in 1864, but his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, is killed by the assassin's bullet. Perhaps because of this, or perhaps because the campaigns of terror by the former southern slaveholders against the newly freed slaves, he and the Radical Republicans set about fundamentally restructuring the South.

On the precedent set by West Virginia's admission to the Union in 1863, five new states are created, recognizing preexisting governments in Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia; these are Tumbigbee, in northern Mississippi; South Alabama, in Alabama; Etowah in eastern Alabama and northern Georgia; and Oconee in central Georgia. Later, an additional state of Tampa is carved out of central Florida, and the state of Tidewater is created out of portions of southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina. The purpose here is unabashed gerrymandering of the post-slavery political system: while an absolute majority of freedmen in the population of Mississippi, Louisiana, and South Carolina lends support to their Reconstruction governments, the Radical Republicans seek to disperse and diminish the power of the former slaveholding class and their supporters as much as possible. All five new state governments have majority non-white populations, except Tampa, and all five are staunch supporters of the Republican party.

The former confederates respond with multiple risings against federal troops and campaigns of terror against what freedmen and natives they can get their hands on. Due to lack of progress on Reconstruction in Texas specifically, the governor of the Fifth Military District, Philip Sheridan, recommends in 1869 that Texas be subdivided into as many as six or seven states, and accomodationist policies be pursued with native Americans in the western parts of the district to reduce the difficulties of pacifying the region. Texas will be divided twice; first, the western part of the state will be split off as West Texas in 1873, and then in the 1880s, West Texas will be divided into Pecos in the south, and Canadia, in the north.

The pattern of western colonization is, alas, not too different from our own history, either; outside the South, the federal government remains pretty hostile to native tribes, and there are frequent conflicts with white settlers. But Nevada is not rushed into the Union in 1864; the vast expanse of territory between Kansas and California will be divided into only two states, Utah and New Mexico; and after Idaho is admitted as a state in 1890, the last territorial region of the contiguous United States will be the rump of the Nebraska Territory, now called Dakotia.

In this timeline, the 1870s turn out rather differently for the Republicans: the Coinage Act of 1873 is not passed, no end to Reconstruction is negotiated in 1876, and without a nearly as severe economic depression (and with the memory of Confederate postwar atrocities in the previous decade still quite fresh), there is no desire to negotiate a premature end to Reconstruction in 1876, nor a willingness to abandon Reconstruction state governments to the Redeemers. Republicans are also assured support from the new states of the South, and remain a relatively popular (and populist) party. It is the Democrats who will try to turn to business interests to gain support in the late 19th century, as their former base of power in the South rapidly dies out. They largely fail; instead, the party ceases to exist entirely. The Fourth Party System is inaugurated in 1892 by the election of William McKinley on the Progress Party ticket, supported by a coalition of progressives, business interests, and imperialists in the Teddy Roosevelt mold.

One side effect of these changes is that the Republicans do not attempt to split the rump territorial region into as many states as possible to increase their advantage in the Senate; instead, Dakotia is rather neglected by the federal government, which shoves defeated Indian tribes into it while making only halfhearted attempts to maintain order. This region will not become a state until the 1920s (admitted at the same time as Hawaii), though it won't be the last state--that will be Washington D.C. and Alaska in 1962.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yet another selection of some of the better names I've come across in Regency era newspapers recently.

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

this is a really interesting firsthand account. thanks! being 50k less in debt is certainly nothing to sneeze at, but it definitely seems like the kind of finding that doesn't get discussed too much in the context of these studies.

i find this article really weird and bad. the argument seems to be that because cash transfers don't help with a lot of proxy metrics for poverty and wellbeing, they do not help with poverty? but poverty is strictly a function of income; there is literally no way that cash transfers do not help with that, except in situations like the conservative hypothetical of people immediately spending the entire transfer on lottery tickets, booze, and drugs (which we have robust evidence does not happen). like, if the question is "how do we eliminate poverty?" then "does this intervention reduce stress levels" is just... completely the wrong question to ask! we are concerned about poverty, not stress. stress might be one negative outcome of poverty, but "how do we eliminate stress?" is in fact a completely different problem!

for sure social science has spent many years trying to show that poverty has lots of other negative side effects like increasing stress, and this is in a sense an argument that people should care more about poverty elimination. but saying "our poverty elimination program eliminates poverty but not stress" is (in the most charitable interpretation i can think of) getting mixed up and reframing secondary negative effects as the only reason to care about poverty.

luckily the same outlet published a pretty solid rebuttal by matt bruenig, arguing that the focus on proxy metrics comes from the idea of human capital development which, again, is not the same thing as eliminating poverty:

Piper’s conclusions are wrong because her method of arriving at them is wrong. Her piece and subsequent comments under the piece make it clear that Piper first became aware of cash benefits in the context of development programs in low-income countries. Those programs are designed as alternatives to other development strategies and thus focus on various developmental measures. This has nothing at all to do with cash benefit programs in high-income welfare states, which exist for completely different purposes. Had Piper actually looked into the long literature on Western welfare states, rather than clumsily apply certain effective altruist ideas about the developing world to America, she probably would have approached her argument much differently. As recounted in Gøsta Esping-Andersen’s The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, the social-democratic welfare state, which exists in the low-poverty Nordic nations, focuses on providing universal benefits — including cash — to its population in order to maximize equality and level living standards, provide workers refuge from the labor market, and promote individual autonomy by making people less reliant on family transfers to get by. Cash benefits do all of those things, even if they don’t lead to “human capital improvements.”

you can of course argue that human capital development is more important than poverty elimination stricto sensu, or even that we should do the former and not the latter. that is, however, a completely separate question from the empirical question of "do direct cash transfers reduce poverty," which we have a mountain of solid evidence that yes in fact they do. and seems predicated on the assumption that "the poor" are a static class and that, once uplifted from that state, society will never need anti-poverty interventions again. this is a very weird and very unrealistic view of poverty.

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

schmand, schlagsahne, saure sahne, yoghurt, creme fraiche. not to mention the endless varieties of fresh and cream cheeses. how many ways can you ferment cream. why do they all come in identical containers at the grocery store. what ancient conspiracy of pastoralists rules society from behind the scenes, atop their udder-shaped thrones.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

it would be great if the question piper had asked was centered on "does giving people more money impact problems we know are directly related to not having enough money, like food scarcity, housing precarity, or healthcare." she focuses on metrics like stress level, child development, BMI, self-reported relationship quality with children, and mentions food security in relationship to only one study. she talks about health outcomes, but that seems to me to be a more nebulous measure than healthcare access, in that it depends on more inputs (though it's easier to measure).

In other words, if you give someone $1000 a month without making much of change in their housing situation, food security, health, stress level, life satisfaction, or connection with their family, but you can now move them from the "in poverty" to the "not in poverty" column on a spreadsheet, is that money well spent or should you have done something else with it?

if your goal is poverty elimination, i think so? like i think poverty is intrinsically bad, and is a social ill, apart from any other second-order effects we might care to measure, and i think this is a point where bruenig and i agree. and it is sort of intrinsically an income problem. more conceptually, i am certain that not having enough money causes people problems, and much less certain that the indirect metrics which piper seems mostly concerned with accurately and completely capture the picture of why not having enough money causes people problems.

to put it another way, if there were evil gnomes that kicked poor people in the shins, and giving people $1500 bucks a month made the gnomes go away, but didn't improve their reported outcome on various survey metrics, i still think giving people money so the evil gnomes stopped kicking them in the shins would be a good intervention, and it would be permissible for us to say it was good on fairly obvious grounds. now, i don't want it to come across like i think survey data is useless and egghead statistics types don't know what they're doing. but at a certain point i think the anti-UBI position here misses the forest for the trees and ends up somewhere worrying close to "we can't even be sure if having money is good or not."

i find this article really weird and bad. the argument seems to be that because cash transfers don't help with a lot of proxy metrics for poverty and wellbeing, they do not help with poverty? but poverty is strictly a function of income; there is literally no way that cash transfers do not help with that, except in situations like the conservative hypothetical of people immediately spending the entire transfer on lottery tickets, booze, and drugs (which we have robust evidence does not happen). like, if the question is "how do we eliminate poverty?" then "does this intervention reduce stress levels" is just... completely the wrong question to ask! we are concerned about poverty, not stress. stress might be one negative outcome of poverty, but "how do we eliminate stress?" is in fact a completely different problem!

for sure social science has spent many years trying to show that poverty has lots of other negative side effects like increasing stress, and this is in a sense an argument that people should care more about poverty elimination. but saying "our poverty elimination program eliminates poverty but not stress" is (in the most charitable interpretation i can think of) getting mixed up and reframing secondary negative effects as the only reason to care about poverty.

luckily the same outlet published a pretty solid rebuttal by matt bruenig, arguing that the focus on proxy metrics comes from the idea of human capital development which, again, is not the same thing as eliminating poverty:

Piper’s conclusions are wrong because her method of arriving at them is wrong. Her piece and subsequent comments under the piece make it clear that Piper first became aware of cash benefits in the context of development programs in low-income countries. Those programs are designed as alternatives to other development strategies and thus focus on various developmental measures. This has nothing at all to do with cash benefit programs in high-income welfare states, which exist for completely different purposes. Had Piper actually looked into the long literature on Western welfare states, rather than clumsily apply certain effective altruist ideas about the developing world to America, she probably would have approached her argument much differently. As recounted in Gøsta Esping-Andersen’s The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, the social-democratic welfare state, which exists in the low-poverty Nordic nations, focuses on providing universal benefits — including cash — to its population in order to maximize equality and level living standards, provide workers refuge from the labor market, and promote individual autonomy by making people less reliant on family transfers to get by. Cash benefits do all of those things, even if they don’t lead to “human capital improvements.”

you can of course argue that human capital development is more important than poverty elimination stricto sensu, or even that we should do the former and not the latter. that is, however, a completely separate question from the empirical question of "do direct cash transfers reduce poverty," which we have a mountain of solid evidence that yes in fact they do. and seems predicated on the assumption that "the poor" are a static class and that, once uplifted from that state, society will never need anti-poverty interventions again. this is a very weird and very unrealistic view of poverty.

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

also, minor point, but if direct cash transfers work in finland but don't work in the united states, that is a fascinating problem worth considering in depth. certainly worth examining the studies that show that critically! i think shrugging and going "oh well, finland is an odd place" and moving on is very annoying!

#that is the kind of situation that should make you strongly suspect that one set of studies or other is wrong#(or both)#or that what were taken to be commensurate interventions were in fact not#or *some* bigger methodological or theoretical problem

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

piper's rebuttal to the rebuttal is also weird. it immediately moves away from the empirical questions and into policy strategy questions like how to spend the marginal dollar available for social spending and legislative strategy, and while these are also interesting questions, they are not the question originally being raised! the question originally being raised was "do cash transfers reduce poverty" and piper argued that they don't, by pointing to metrics that are not poverty metrics, and bruenig pointed out that they do.

also, just as a rhetorical tic, this bugs me:

I don’t think this is an accurate model of what holds back expansions of the social safety net. Instead, I suspect the opposite: Many people who would support the safety net if it were to succeed, oppose it precisely because they perceive it as failing — and perceive its defenders as lying. If we treat every conversation as primarily about advertising for programs rather than for figuring out what works and what doesn’t, we fail to get our politicians good information about which priorities they should pursue when in power.

clearly the implication here is that piper opposes the social safety net because she percieves it as failing and its defenders as lying, but by fobbing that view off onto an undefined third party she doesn't have to actually take that position, and instead frames the issue as one of dispassionate political strategy. a lot of columnists and opinion writers do this kind of thing, this "many people are saying, but not me, i'm not, don't argue with me," and i think it's cowardly! matt yglesias does this a lot. i think you should own your beliefs!

Bruenig laments the move in policy and development circles toward measuring outcomes and running studies.

this is just a lie? and a pretty snarky one at that. bruenig seems to be criticizing the use of proxy outcomes over direct outcomes. you cannot cite a statistic like "the U.S. began expanding the Social Security old-age pension in the middle of last century, the elderly poverty rate declined from 35% to 10%, around where it remains today" unless you care about measuring outcomes!

the alternative programs piper points to like building housing and improving education are all i think good things, but treating existing US welfare programs as being more or less the same as direct cash transfers baffles me. the whole reason i got interested in UBI as an idea was people like piper posting here on tumblr about how inefficient existing welfare programs, with all their means testing and barriers for qualification and indirect mechanisms are; we have not experimented with giving the entirety of the american gdp in 1969 to people in the form of direct cash transfers! we haven't even come close! so to act like the large size of current social programs (a lot of which does not go to the poor! you don't have to be poor to get social security!) is evidence direct cash transfers don't work is weird. i feel like 2015 kelsey piper would have objections!

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

i find this article really weird and bad. the argument seems to be that because cash transfers don't help with a lot of proxy metrics for poverty and wellbeing, they do not help with poverty? but poverty is strictly a function of income; there is literally no way that cash transfers do not help with that, except in situations like the conservative hypothetical of people immediately spending the entire transfer on lottery tickets, booze, and drugs (which we have robust evidence does not happen). like, if the question is "how do we eliminate poverty?" then "does this intervention reduce stress levels" is just... completely the wrong question to ask! we are concerned about poverty, not stress. stress might be one negative outcome of poverty, but "how do we eliminate stress?" is in fact a completely different problem!

for sure social science has spent many years trying to show that poverty has lots of other negative side effects like increasing stress, and this is in a sense an argument that people should care more about poverty elimination. but saying "our poverty elimination program eliminates poverty but not stress" is (in the most charitable interpretation i can think of) getting mixed up and reframing secondary negative effects as the only reason to care about poverty.

luckily the same outlet published a pretty solid rebuttal by matt bruenig, arguing that the focus on proxy metrics comes from the idea of human capital development which, again, is not the same thing as eliminating poverty:

Piper’s conclusions are wrong because her method of arriving at them is wrong. Her piece and subsequent comments under the piece make it clear that Piper first became aware of cash benefits in the context of development programs in low-income countries. Those programs are designed as alternatives to other development strategies and thus focus on various developmental measures. This has nothing at all to do with cash benefit programs in high-income welfare states, which exist for completely different purposes. Had Piper actually looked into the long literature on Western welfare states, rather than clumsily apply certain effective altruist ideas about the developing world to America, she probably would have approached her argument much differently. As recounted in Gøsta Esping-Andersen’s The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, the social-democratic welfare state, which exists in the low-poverty Nordic nations, focuses on providing universal benefits — including cash — to its population in order to maximize equality and level living standards, provide workers refuge from the labor market, and promote individual autonomy by making people less reliant on family transfers to get by. Cash benefits do all of those things, even if they don’t lead to “human capital improvements.”

you can of course argue that human capital development is more important than poverty elimination stricto sensu, or even that we should do the former and not the latter. that is, however, a completely separate question from the empirical question of "do direct cash transfers reduce poverty," which we have a mountain of solid evidence that yes in fact they do. and seems predicated on the assumption that "the poor" are a static class and that, once uplifted from that state, society will never need anti-poverty interventions again. this is a very weird and very unrealistic view of poverty.

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

those land crocodiles are the stuff of bad dreams lol

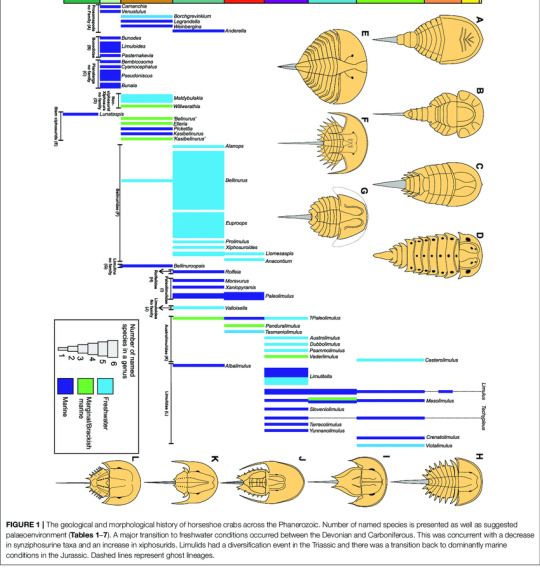

Other posts go into more detail on this, but if you ever find a meme-like claim that a certain taxon has "never evolved" since so and so millions of years, it's most likely that, just a meme.

Crocodiles? Land crocodiles were, at many points of history, as common as amphibious crocodiles. In South America when it was a island-continent, they were among the main predators.

Horseshoe crabs? They have a rather well documented evolutionary history.

Sharks? Buddy you aren't even ready to know how fucking weird prehistoric sharks were:

(in order: Helicoprion (ONE reconstruction, we still don't have any idea how it worked), Stethacanthus, Aquilolamna)

Yes, for sure, some life forms have been very successful, I won't pretend the amphibious crocodile body plan hasn't been very succesful and conservative since the mesozoic. Plants are also remarkably conservative (not as much as you'd think, though). But every time you see the "X hasn't changed at all for millions of years, it's the perfect creature!" it's just a meme that obscures real life evolution and diversity.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

as i understand it the self-mythologizing of some strands of neopaganism in the 20th century involved the idea that real practitioners of pagan traditions were often being persecuted during witch trials, which helped establish a link between modern neopagan traditions and the paganism of prechristian antiquity--if authentic pagan traditions had survived until the 1700s, then perhaps they had survived until the 1950s. iirc some of this speculation was based on some, uh, highly contested academic work?

anyway, in that framework, salem might be no different than any other site of martyrdom, and given the lack of any really ancient pagan sites in the united states that could be associated with wicca or related neopagan movements (vs like stonehenge or gamla uppsala or something), salem is the only place you'd have to work with when it comes to trying to create a physical connection to a mythologized past.

the modern town of salem has turned the 17th century witch trials--in a locale which is, since the 18th century, no longer even part of salem--into a hyperrealist vehicle for 20th century spiritual grifters and a glorified tourist trap, a kind of mecca for a fake tradition invented out of whole cloth by an englishman in the 1950s. which is just about the most american thing there is. as american as puritanism and witch hunts, as a matter of fact.

297 notes

·

View notes

Note

funny thing about german sandwich bread: a lot of it--at least as carried by the budget grocery store next to where i live--is advertised as American Style Toast ("toast" is the German word for sandwich bread). so the thing that much german sandwich bread calls back to is explicitly crappy american sandwich bread

personally my favorite brand of sandwich bread is Roman Meal, which i don't think i've seen in a grocery store since the Compton's near our house got replaced with a Harris Teeter. wikipedia says the brand has since been sold so who knows if it's even the same recipe anymore.

You've abandoned your American roots and become a European at heart. Only some bastard Euro would claim you can get good store-bought sandwich bread.

Surely it is the bastard Euro who sneers at all prepackaged sandwich bread?

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

You've abandoned your American roots and become a European at heart. Only some bastard Euro would claim you can get good store-bought sandwich bread.

Surely it is the bastard Euro who sneers at all prepackaged sandwich bread?

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

A lot of foods can be fun to learn to make yourself but there’s really no reason to—mayonnaise is a pretty generic product. If i just want to make sandwiches, i can get very good sandwich bread for very little money. But i have recently discovered that homemade guacamole and salsa are not only relatively easy but offer an extremely high deliciousness return ratio. I guess it helps that I don’t like any of the salsa brands the stores in my neighborhood carry.

48 notes

·

View notes

Note

Pre-telescope measurements in the 16th century were wild. Tycho Brahe my beloved

Dude had wicked good eyeballs!

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Don't forget that those guys had an advantage in that stars were way way way more visible before modern light pollution

I assure you i am not forgetting about light pollution, but even without it the human eye is a fairly limited (and variable quality) instrument. Especially for observing faint stars, which can do this nasty trick of vanishing when you look directly at them. Though apparently Ulugh Beg had a giant sextant built into his observatory in the 1430s, which is pretty cool.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

I mean, sure, I’m specifically thinking that even in dark sky conditions you can discern, what, a few thousand stars? And with good instruments you can measure their positions to maybe a tenth of a degree? Though that’s hampered by having poor clocks, low-quality catalogues (which is why you’re compiling your own) and having to do all the math (including trigonometry) by hand. Huge pain in the ass!

incredible that people managed to do moderately useful astronomy before the invention of optics. maybe this seems more wonderful to me because without glasses i would be blind as a bat. stars would be an entirely theoretical concept to me. and there were people in the middle ages writing whole ass star catalogues (pretty good ones!) just using their eyeballs.

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

incredible that people managed to do moderately useful astronomy before the invention of optics. maybe this seems more wonderful to me because without glasses i would be blind as a bat. stars would be an entirely theoretical concept to me. and there were people in the middle ages writing whole ass star catalogues (pretty good ones!) just using their eyeballs.

94 notes

·

View notes