Welcome to the Tumblr blog for Uncharted Territory. The goal of this site is to offer stimulating, challenging items for you to analyze, reflect upon and respond to. Visit this site regularly for new material. You’ll find diverse posts here that explore...

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Using Uncharted Territory to Study Authors’ Craft: The Power of Micro-Mentor Texts to Improve Reading and Writing

In her book Micro Mentor Texts: Using Short Passages from Great Books to Teach Writer’s Craft (Scholastic 2022), Penny Kittle offers useful and engaging ideas for new ways to use Uncharted Territory to deepen students’ study of the craft of reading and writing. In short, she encourages you to use the many different texts in Uncharted Territory as “micro-mentor texts.”

Matt de la Peña, author of Last Stop on Market Street, argues in his foreword to Kittle’s book that using such mentor and model texts “[extends] an invitation [to] teachers [that] changes the way…students engage with writing” (7). As de la Peña observes, “the best writing teacher in the world is great literature” (7). Using the texts from Uncharted Territory as a treasure chest of models, you can follow Penny Kittle’s example by “exploring with [your] students gorgeous passages” that you will find in the stories, essays, and other nonfiction texts of Uncharted Territory. Penny repeatedly emphasizes that such careful attention to the study of writers’ craft has the added benefit of improving not only students’ writing but also their reading skills.

Asking students to engage with the texts in this way places them in the role of writers, for it invites students to enter into the decisions that writers make when they choose one word or move over another. In other words, by using the texts in Uncharted as opportunities to study the authors’ craft, we give students room to discover and develop their own voice by showing them how many ways there are to write about a certain topic or genre such as the personal literacy narrative.

Penny breaks down her approach to the selection and use of mentor texts into a few short and intuitive steps:

Notice: Look for those moves the writer makes in a text that you can use as models with your students. Talk through with your students what you notice in this text so you can help them to see what the author is doing, how and why they might be doing that.

Imitate: Have your students imitate the moves the author makes by trying them out in the same way artists might make different sketches of a figure to see the different ways they could approach it. During this stage, Penny writes with her students, sharing her own process and choices about the moves she makes and how they relate to the mentor text.

Your Turn: Students now draw from a set of specific mentor texts that Penny (or you, I, or any other teacher) selects for reasons related to what the students are writing or need to learn. Here, students continue to imitate the models as they adapt the model texts to their own writing.

Their Turn: Finally, Penny invites students to seek out their own models to study and use as students continue to work on their own writing. In this case, you might let kids choose from a set of texts within one of the units of Uncharted Territory or direct them to choose additional texts from the titles listed by genre or theme in the appendices.

If, for example, I was sketching out a lesson sequence related to ways to open up or write a literacy narrative, I might ask students to use these readings from Uncharted as mentor texts to get them started:

“Blue-Collar Brilliance,” by Mike Rose, directing them to focus on the first two pages (20-21) as a model for one way to set up such an essay.

“To Keep It Holy,” from Educated, Tara Westover, suggesting they study page 72 and how it compares with the way Rose begins his narrative.

From Lab Girl, by Hope Jahren, paying close attention to pages 529-530, especially how she begins her story and how it compares with the other two.

From here, students could find many other texts, or excerpts from these micro mentor texts to study and use as models when it is time to write their own. Penny Kittle reminds us at the end of her wonderful book that “great writer’s craft is everywhere” (168). Good writing, as Penny might say, is wherever you find it, including in your own classroom.

Misc. Notes/Links/Resources

Penny Kittle’s Website (a wealth of wisdom and additional resources!)

“Teaching the Writer’s Craft with Micro Mentor Texts,” Penny Kittle (Edutopia)

Interview: Penny Kittle on Teaching Writer’s Craft with Micro Mentor Texts (Literacy Lenses podcast)

#reading#education#uncharted territory#author craft#biography#analyzing cause and effect#argument#persuasion#comparing and contrasting#describing#literacy narratives#instructional resources and recommendations#Mike Rose#Tara Westover#hope jahren

0 notes

Text

Creating Conversations Through And About Texts

Many of the stories, essays, op/eds, speeches, and articles you find on Viet Thanh Nguyen’s website or in his books are a bit like Swiss Army knives in the hands of a teacher trying to help their students make sense of the modern world. You can use many of his pieces in conjunction with each other or place them alongside other works by other authors as a way of extending the conversation a writer, such as Mohsin Hamid, is inviting us to have about anything from immigration to identity, obligation to relationships. (These are, from my perspective, two of the most relevant, interesting, and important writers when it comes to insights about our country, time zeitgeist, and the direction things seem to be going for America.)

In my own class, I use a number of different pieces by Nguyen in addition to his excellent essay “On Being a Refugee, an American—and a Human Being,” which appears in the second edition of Uncharted Territory. My students read a number of his essays during our inquiry into human migration when we are reading Mohsin Hamid’s amazing novel Exit West (which might be my favorite novel to teach these days). Nguyen is such a remarkable essayist because he has so many moves for students to watch and learn from. He writes in the same essays often about America as a refugee and immigrant and then, in the next sentence, jumps to the other side of the court and writes as an American about migrants and refugees, moving between identities and perspectives with the subtlest shift of a pronoun or tense.

In the last few years, I have brought his work into my junior class in a way that has proven both important and useful. In the past, our program had assigned Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried in the junior English class. It is an amazing book. However, my classes at Middle College High School the last few years have consisted of roughly 50% Asian students and roughly 75% girls, a profound shift for me after being at Burlingame High School for so many years.

In order to bring one author (O’Brien) into conversation with another (Nguyen) and ensure there are new voices and perspectives in the class, I applied to the district to get funding for Nguyen’s short story collection The Refugees (which has a few choice essays at the end). His essay, “On Being a Refugee, an American—and a Human Being” works perfectly as a bridge between the two books and helps me to extend the conversation the two longer works invite us to have. In addition, in his short story “On the Rainy River” (which appears in the Credo unit of the second edition of Uncharted Territory), O’Brien explores questions of fleeing one’s country in response to the Vietnam War. These two pieces in Uncharted Territory along with Emma Lazarus’s poem “The New Colossus,” (also in the Uncharted Credo unit), which Nguyen discusses in his essay, give you the foundation to start a conversation about some of these common themes through the texts. Alternatively, they can create a context to talk and write about the texts in a more analytical, rhetorical way if you prefer.

One additional benefit of using the work of Viet Thanh Nguyen: people do interesting things with his texts. For example, when my students read his essay “On True War Stories,” which is a direct response to Tim O’Brien’s story “How to Tell a True War Story,” from The Things They Carried, students can choose three different versions or formats of Nguyen’s essay:

“On True War Stories” (Original Essay/Clean Text)

“On True War Stories” (Illustrated Version by Matt Huynh)

“On True War Stories” (Annotated Version)

As I have many students who are obsessed with graphic novels, manga, and other variations on comics, they really enjoy having these choices.

This graphic option also creates one additional opportunity to extend the conversation and incorporate a wider range of genres into my class: I can link to and have my students read a portion of Thi Bui’s wonderful graphic memoir of her family’s journey to America from Vietnam from The Best They Could Do and ask them to compare her perspective and experiences with Nguyen’s.

#reading#education#uncharted territory#research#identity#biography#cultural analysis#memoirs and personal essays#comparing and contrasting#narrating#analyzing cause and effect

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Challenge of Teaching and Talking During Troubled Times

Teachers these days often find themselves caught up in what authors Peter Boghossian and James Lindsay call “impossible conversations,” which they define as “conversations that feel futile because they take place across a seemingly unbridgeable gulf of disagreement in ideas, beliefs, morals, politics, or worldviews” (2019, 3). For many years, teachers have embraced the idea of “entering the conversation” as though such encounters would inevitably take place around a nice round table in a café on a pleasant afternoon, each person engaging “in ongoing conversations about vitally important academic and public issues” as Graff and Birkenstein describe in They Say / I Say (2021, xxi). The problem, however, is that instead of developing their arguments “by looking inward…[and] listening carefully to what others are saying [about] and [how they are] engaging with other views,” students, parents, administrators, even colleagues and community leaders often “enter the conversation” these days as gladiators once did the coliseum or as Teddy Roosevelt urged us to enter the arena, in a state of what Amanda Ripley calls “high conflict”:

[High conflict] is the mysterious force that incites people to lose their minds in ideological disputes, political feuds, [or efforts to prevent certain books from being taught or instructional methods from being used]. The force that causes us to lie awake at night obsessed by a conflict with a coworker or a sibling or a politician we have never met. (2021, 3)

Whether we are classroom teachers, department chairs, or program coordinators tasked with deciding on whether to purchase the new edition of Uncharted Territory, add Toni Morrison’s Beloved to the curriculum, or teach a new unit in an American history course, we often find ourselves challenged not just from those on the conservative end of the political spectrum but from those on the progressive end of that same continuum. They increasingly oppose the texts, topics, or instructional techniques teachers choose with equal passion—but different concerns and rationales.

Over the years, I have witnessed, experienced, or heard of challenges to science, history, and even mathematics textbooks due to their content; to instructional methods or approaches in English, history classes, and most other classes; to topics discussed, topics omitted, topics twisted and transformed in ways that caused confusion or concern among various parties. I know teachers who have been applauded by students and parents for incorporating such elements of Marxist Theory into their curriculum yet simultaneously attacked by others in the same class whose families had fled Russia after being persecuted or having members of their families killed by Communists. These and other conflicts in the classroom, and within the culture at large, are examined with great intelligence and insight by Deborah Appleman in her new book Literature and the New Culture Wars: Triggers, Cancel Culture, and the Teacher's Dilemma (2022).

Within the last several years, exacerbated no doubt by the strains of the pandemic, I have watched such conflagrations of views and values erupt suddenly and with often fearsome intensity on local networks such as Nextdoor, community blogs, comments sections in local newspapers and community bulletin boards, school board meetings, text chats between colleagues, Twitter, Facebook, as well as department and faculty meetings.

What to do? How do we think about our work and the response of the various stakeholders to that work? How are we to honor our own professional knowledge and priorities while making room to listen to and consider those of students, parents, and anyone else who sees themselves as having a legitimate interest in what children study? Recently, I worked with teachers from all subject areas in Idaho to help them design curriculum units that incorporate, as mandated by the terms of their grant from the state educational agency, “impossible conversations” around “contended issues” that they were facing in their various schools and communities.

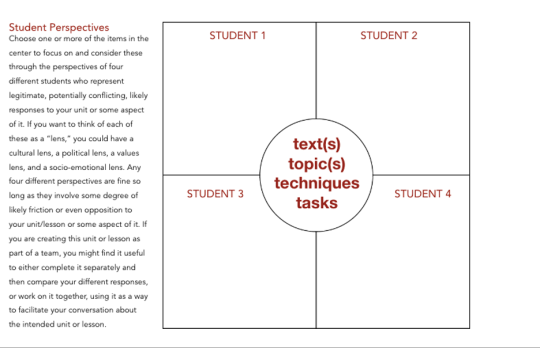

Instead of offering specific phrases or templates to help you find the words to navigate such potentially fraught discussions, I have included several tools below that we used in Idaho to help you think about how these various stakeholders would respond to a text, a topic, or an instructional technique in your class. When we apply the elements of design thinking, for example, any such process of choosing or creating content for our classes begins by considering the user, which is to say your students or whoever will be using the intended text or technique. Use the following three diagrams to help you think about how students or others might respond—and why; then consider whether you need to revise or refine the content without feeling compelled to replace it.

The first of the three diagrams asks you to do some thinking about four different ways adults—parents, guardians, administrators, or community members—might respond to your plans. The second one asks you to use a variation of the same diagram to think about how four students with different perspectives, needs, or values will likely respond. Finally, the third one asks you to think about likely points of friction with colleagues on your team, in your department, or in another context where tensions are likely to arise.

One last idea that might be useful and effective with a range of people who may resist or even reject your intended unit or lesson is empathy interviews. Shane Safir and Jamila Dugan describe these interviews as a way to “help us listen for how a person feels and perceives” whatever we are trying to teach or asking them to do (2021, 177). While they suggest doing these interviews one-on-one, I found this example I created to help me have a discussion with kids about reading worked just fine if all students fill them out and then I follow up as needed if I had questions.

While this sample empathy interview is not necessarily related to topics, texts, or techniques that are likely to devolve into serious tension, it provides a useful model to adapt for your own needs with your students, adult stakeholders, or colleagues about issues that are likely to become a source of trouble.

These controversies and coordinated assaults on teachers, departments, and districts over what they teach and how they teach it are not new. Such crises are often started or magnified by what Ripley calls “conflict entrepreneurs” (i.e., people who start or accelerate conflicts for their own personal aims). Yet they have been with us in this country for a long time. In the 1920s, censors came after D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and James Joyce’s Ulysses, which the judge said could not be obscene for he could not even understand it himself and thus could not imagine it posing any threat to young school-age children (Birmingham 2014, 194). In 1925, you had the Snopes trial over the teaching of evolution, a “conversation” that continues to this day and plays out in science classes and textbooks.

In his book Storm in the Mountains: A Case Study of Censorship, Conflict, and Consciousness (1988), James Moffett examined in depth a famous conflict in West Virginia in 1974 about issues related to the teaching of American history and the textbooks the school used. In a chapter titled “Race War, Holy War,” Moffett interviewed a staff member of the Kanawha County School District about the conflict, which became very heated. The woman said, “Textbooks weren’t the issue. No one will ever convince me. The major issue was a political one and had to do with the black-and-white issue” (94). The woman’s remark is a fitting example of what Amanda Ripley says is often at the heart of most “high conflicts”: an “understory,” which she defines as “the thing the conflict is really about, underneath the usual talking points” (xii).

So we might end here by saying that a good place to begin when you are in or think you could face any potentially high conflict situation with students or other stakeholders is to ask just what is the real issue, the understory that can help you as a teacher understand what those involved are actually upset about so you can better understand what is motivating their emotions, thoughts, and actions. In other words, seek first to understand—then to be understood.

Works Cited and Related Resources

Appleman, Deborah. Literature and the New Culture Wars: Triggers, Cancel Culture, and the Teacher's Dilemma. New York: W. W. Norton. (2022).

Birmingham, Kevin. The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce’s Ulysses. New York: Penguin. 2014.

Boghossian, Peter and Lindsay, James. How to Have Impossible Conversations: A Very Practical Guide. New York: Hachette. 2019.

Graff, Gerald, Birkenstein, Cathy, and Durst, Russel. They Say/I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing (with Readings). High School Edition. Fifth edition. New York: W. W. Norton. 2021.

Moffett, James. Storm in the Mountains: A Case Study of Censorship, Conflict, and Consciousness. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. 1988.

Ripley, Amanda. High Conflict: Why We Get Trapped and How We Get Out. New York: Simon and Schuster. 2021.

Safir, Shane and Dugan, Jamila. Street Data: A Next-Generation Model for Equity, Pedagogy, and School Transformation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. 2021.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Decisive Moment: “Who Am I and Why Am I Here?”

Vice presidential candidate James Stockdale famously began his 1992 debate with Dan Quayle by saying that the question on most people’s mind that day was: “Who am I and why am I here?” It was a decisive moment in the campaign. It is the sort of question we ask students to think about in relation to their own life and people they study in our classes. It is the sort of moment students are often asked to write about on a college application essay. It is often the pivotal moment in a novel or a play we ask students to read. (The French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson is credited with coining the term “decisive moment.”)

One person who was confronted with that question (“Who am I and why am I here?”) at a young age was U.S. Congressman and Civil Rights leader John Lewis. At the age of sixteen, he was faced such a moment not only when he asked this question of himself, but when he was also asked the same question by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. In the excerpt included here, which comes from his three-volume graphic memoir titled March, Lewis recounts his first meeting with Dr. King.

This is an engaging and powerful way to bring students into the discussion of education as we often experience it inside and outside of the classroom. As Mike Rose reminds us in his “Blue Collar Brilliance,” (in the Education section of Uncharted), learning in the workplace and the world outside of the classroom is no less important to students’ education. The story John Lewis begins to tell in this excerpt from his memoir marks the beginning of his apprenticeship into politics, signals the start of his real vocation, and initiates the process through which he would ultimately formulate the identity and reputation that made his life so worthy of study and his loss in 2020 so difficult to bear.

Whether your students are reading works related to civil rights in the United States or more personal moments such as the one Tim O’Brien explores in his short story “On the Rainy River,” in Uncharted, this graphic memoir by and about John Lewis and his decisive moment at sixteen makes for a substantive addition to your curriculum.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paper or Plastic? Reading Pages vs. Screens

We all find ourselves, both teachers and students, spending more time reading on screens than is good for us. And the new year only suggests we will continue to spend as much time as we did in 2021 reading electronically as we slowly work through the challenges that COVID continues to present to us.

We have all grown more accustomed to reading just about anything on a variety of screens: cell phones, iPads, eBook readers such as the Kindle, Chromebooks and their fancier cousin the high resolution laptop, and the big screens at the front of the class that many of us (including myself) associate with the period of hybrid teaching when we began to slowly return from teaching entirely online. To these, we might add the growing popularity of audiobooks, which might be compared to the voice we hear in “the dark cathedral of [our] skull,” as Thomas Lux describes it his wonderful poem “The Voice You Hear When You Read Silently.”

Several recent reports examine the reading experience on screens versus the paper page. The digital version of Uncharted Territory, which I have used on many occasions in my classes, is beautifully designed, mimicking a pristine page while adding useful functions and features. However, these three reports, linked below, raise important questions about how we read screens versus pages. Whether we are assigning kids eBooks, websites, or handouts rendered into PDFs to be read on screens, we should ask ourselves how we should structure the reading experience to ensure they read the material as we intend. My primary approach is to do what I can to prevent them from spacing out and going wide-eyed before the square of light they are pretending to read. This means asking them to stop at specific points in the digital text and respond to questions on paper, turn and talk to a neighbor, or join a full-class discussion about some detail before returning to the text to continue reading.

Further Reading:

https://hechingerreport.org/evidence-increases-for-reading-on-paper-instead-of-screens/

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/reading-paper-screens/

https://www.nngroup.com/articles/f-shaped-pattern-reading-web-content/

#research#reflection#instructional strategies#reading#education#Thomas Lux#Uncharted Territory e-book#text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Extending the Conversation Through Additional Texts and Media

While preparing to teach Frederick Douglass’s “To My Old Master, Thomas Auld” (see pg. 828 in Uncharted Territory 2e), I wanted to accomplish several things. I wanted students to learn about what open letters are and why people write them. I also wanted to continue our conversation about reading different types of texts, in this case primary source documents, online articles, and editorials. I hoped to ensure that my students saw the connection between what they were reading by Douglass and what they see in the world they live in today.

As I was preparing the lesson the night before, I encountered an incredible article in my feed from nationalgeographic.com: “This Is Not a Lesson in Forgiveness: Why Frederick Douglass Met with His Former Enslaver.” It offers students a rare opportunity to see how relationships evolve over time as the people themselves do. In other words, having them read this article from nationalgeographic.com asks them to compare how the relationship between the two changed and why, but also why it matters given what Douglass said about Auld in his Narrative.

Instead of writing about what we did in class that day with these texts, I thought it would be more useful and interesting to just include a link to my actual lesson plan (as kids saw it) from that day. My primary aim through this unit is to establish a culture of inquiry and rigor in my classroom in those early weeks, while also emphasizing that we are going to engage in discussions about the ideas that interest them and the skills they need to be ready to use to get off to a good start. We will, it is worth pointing out, return to Frederick Douglass and his story throughout the semester, as one of the questions on the final invite students to examine the ways in which Frederick Douglass and Jay Gatsby are similar.

#reading#education#reading recommendations#in the classroom: preparation#Frederick Douglass#To My Old Master Thomas Auld#National Geographic#text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Weekly Poem

This year I have brought back something I did for many years, but the chaos of the last two years has made difficult to do: having my students read the same poem every day for a week. Though I do not always use a poem from Uncharted Territory, the poem I will focus on here is Pat Mora’s gem of a poem titled “Two Worlds” (see page 478 in Uncharted 2e), which has a curious number of alternative titles it goes by (“Legal Alien” and “My Own True Name”) that can be interesting to have students consider.

The Weekly Poem has few constraints but the ones it does have, at least in my class, are important. If we are going to read it five times in a week, it needs to be substantive enough to warrant that sort of sustained attention. It should be demanding enough that it challenges them each day but requires little, if any, direct instruction since I am not “teaching” the poem but using it for different purposes than I might if I were actually teaching poetry. I think of it as a daily exercise of their attention. As the poet William Stafford defined it, "A poem is anything said in such a way or put on the page in such a way as to invite from the hearer or reader a certain kind of attention" (from Writing the Australian Crawl: Views on the Writer's Vocation). So, in short, the weekly poem must be short, interesting, accessible, but also demanding in useful, relevant ways.

Using Mora’s “Two Worlds” as a model, we did the following over the course of a week. First, why this poem? It satisfies all the requirements listed above. It was also Hispanic/Latino Heritage Month, so that was a nice bonus but not the main reason for choosing it. We were actually working on the material in chapter 7 of Uncharted, reading all the different texts by and about Frederick Douglass and his experiences of moving between different worlds, since he was biracial. It was a perfect selection for early in the year, during which I was still introducing the practice of the weekly poem.

Over course of the week, we followed a pretty consistent series of steps for the weekly poem, though it inevitably varies depending on the larger context of my class:

Monday: I read it straight through aloud, while they are looking at the text of the poem. I ask them to turn to a partner and simply discuss what they noticed and what questions came up for them. I emphasize that they should not try to figure out “what the poem is about.” We are just reading it to listen to it, to enjoy it, to get the sense and sound of it, use it to foster discussion in class. Total time: 5 minutes

Tuesday: We reread it aloud, using a video or recording of the poet reading it if available. Then I ask them to go through the poem to get the gist of it, to summarize it with a partner without trying to interpret it. In short, to tell their partner what they think is going on (i.e., what people are doing, what is happening, what is being described) in the poem. Total time: 5-6 minutes

Wednesday: I reread it aloud, then ask them to reread it to themselves, focusing this time on the language. When reading Mora’s poem, for example, I want them to look for all the words that have anything to do with the idea of two or division. So, for example, we discuss the prefix bi- and discuss what they noticed after they finish. Total time: 5-7 minutes

Thursday: We reread it—sometimes aloud, sometimes to themselves, other times using a video such as this one when they read sonnet 29 one week—and then I ask them to reread it for some other aspect that seems most accessible but important: imagery, structure, an idea. One week, we read four of Lucille Clifton’s poems to Superman, then finished the week on Friday with her poem “won’t you celebrate with me” (page 805 in Uncharted 2e), which I let Clifton read to us here.

Friday: On Friday, they come in and write about the poem in some way that is meaningful to them, usually in their notebooks. Here is what I asked them to do with Pat Mora’s poem:

In your notebook, write about this idea of passing between “two worlds.” You can write about your own experiences of this, Frederick Douglass’s, or the speaker in the poem here--or just people in general and the different worlds we inhabit, the different identities we inhabit. (I will not require you to share what you write with others…)

Students wrote with great success about the poem at the end of the week. Here’s a representative example from Julyssa Sandoval, a junior in my class:

I think that this idea about passing between “two worlds” relates much to the experience of not feeling like you fit into a certain category. Society today is still very confining and there are so many expectations about people being a certain way or fitting with a certain group. I think that the poet here was trying to convey how they feel isolated in a way. They have to keep switching between worlds, they’re worlds do not accept each other which is why they are separated. I feel like the poet describes her identity as being stretched out between these two worlds, she is constantly fighting both sides. In my personal experience, I can relate because I feel like there is this pressure to have to make your culture proud, but also assimilate to the dominant culture to be accepted. It is hard being able to do both, which is why many people with mixed cultures feel it is hard to be represented and understood. I think that there is very little awareness about how much of a struggle it is being able to be accepted by both sides. Moreover, this struggle is what causes one to feel like they don’t belong in either groups because they are being shunned by each side when they do not conform to either.

I love the weekly poem for many reasons. I start class with a nice poetry boost. I can take roll. I usually try to check in with a student or two who may have been out. I am able to bring in a wider range of voices, perspectives, and experiences. And, as we see from Julyssa’s response, the weekly poem allows me to invite my students to think about ideas important to them while also sharpening their reading skills and strengthening their attention muscles.

#reading#education#reading recommendations#in the classroom: preparation#poetry#poems#Pat Mora#Lucille Clifton#text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Reading Images

Throughout the new chapter “Reading as a Writer,” you find a series of different text types: fiction, nonfiction, primary sources, articles, poems, photographs, artworks, websites, and some that blend formats. The idea behind the chapter is fairly straightforward: each type of text makes its own unique demands of the reader, while sharing certain features with all other types of texts. In other words, while a poem like Robert Hayden’s “Frederick Douglass” asks readers to approach it as a poem that follows certain conventions specific to that format, it is also a text, which is to say a woven thing, just as a photograph is.

Periodically, when discussing concepts such as everything being a text of some sort, made of certain elements, I will put up an image like this, asking my students to think about all the different elements (threads) that make up and create the meaning of a text:

Source

As the American Heritage Dictionary makes clear, the etymology of the word text offers a useful reminder about what the texts we read (or create) consist of:

Middle English texte, from Old French, from Late Latin textus, written account, from Latin, structure, context, body of a passage, from past participle of texere, to weave, fabricate.

When teaching students how to read different types of texts, in this case, photographs, part of that discussion includes the reason why someone would choose one means, method, or medium over another. Why, for example, was Frederick Douglass the most photographed man in America during his time? And how was his use of photographs similar to or different from the way Martin Luther King, Jr. used them during the Civil Rights era nearly a century later?

To reinforce the reading skills emphasized in chapter seven of Uncharted Territory, I ask students to read articles such as this one from the New Republic (“Frederick Douglass’s Faith in Photography”) and compare it with this other article from the New York Times (“Dr. King’s Complex Relationship with the Camera”).

In addition to these two articles, I ask students to read or review "Every Photo Is a Story," an excellent guide provided by the Library of Congress about how to read photographs. If I want them to write about the photographs we are reading, I may have them read or direct them to this excellent resource at Duke University’s Writing Center.

Kids love images. They live in a very visual world to which they are always contributing on one app or another. Making them more critical viewers and producers of those images is one way we can help them be more critical readers and viewers of all texts.

#reading#education#reading recommendations#New York Times#Robert Hayden#text#in the classroom: preparation

0 notes

Text

Beginning Where They Are as Readers, Writers, and Students

Now is that time when we sit down to plot the story of the year ahead for our classes, our students, and ourselves. As with any great story, the year should have those conflicts and tensions that culminate at year’s end with our individual and collective growth. And certainly, our classes will come with plenty of characters to keep things interesting. Regarding plot, Kurt Vonnegut argues in “The Shapes of Stories,” included in the second edition of Uncharted Territory, that there are only so many shapes the story of our lives (and classes) can take. Finally, all great stories have certain themes their authors (or we as English teachers) explore in their quest for clarity and understanding about who we are and why we are here. It’s a challenging but important question to ask ourselves as teachers: What do I want this course I am creating to be about? What is the story I want myself and my students to tell about this course when it is over?

From the beginning of my year, before I have ever met my students, I keep in mind the great tennis player and civil rights leader Arthur Ashe’s admonition that one should “Start where you are. Use what you have. Do what you can.”

In keeping with Ashe’s advice, I devote my earliest efforts to finding out where my students are as readers, writers, thinkers. In response to the American History teachers with whom I collaborate, I developed a unit called “Foundations” that is anchored in the life and literacy of Frederick Douglass. This unit led me to create the chapter in the new edition of Uncharted Territory titled “Reading as a Writer,” in which I emphasize the connections between academic reading and writing. As we move through these different texts—reading, discussing, and writing about them—I am assessing where my students are, while at the same time working hard in those first few weeks to get them where they need to be by using techniques from Uncharted Territory and reading strategies such as those summarized here.

My students enter our program and my class in August needing to be ready not only for the high school classes I teach but the college classes in which they are simultaneously enrolled at Middle College. Many of them are first-generation college students such as I was, all of them juniors who are getting an early start on college through our program. However, as several of the readings in the new edition of Uncharted Territory make clear, just because one goes to college does not mean they know what to do once they get there. That was certainly true for me, as I describe in “My Personal Prologue,” in the new edition of Uncharted.

#education#reading#reading recommendations#kurt vonnegut#arthur ashe#frederick douglass#in the classroom: preparation

0 notes

Text

Personal and Professional Reading: Making Time for What We Love Most

The question I am asked most often by my fellow teachers, whether we are chatting in the halls at a conference, talking about teaching at the Norton booth while they look at a copy of Uncharted Territory, or trading ideas online is: How do you manage to read so much while still teaching full-time? It is a very important question.

Before I talk about HOW I do all that reading while still teaching (eleventh grade English the last few years, FWIW) let me say a few things about WHY I read so much and why I hope you will make time in your personal and professional life this year to read as much as you can. As you will learn when you read “A Personal Prologue,” my literacy narrative in Uncharted Territory, I read very little growing up. In fact, the only book I can honestly recall having read for high school was Bless the Beasts and the Children, which turned out to be a life-changing moment for me, though I could not know it then.

As you will see in other literacy narratives in the new edition of Uncharted Territory, first-generation college students such as myself, Mike Rose, Tara Westover, Jimmy Santiago Baca, and autodidacts such as Frederick Douglass often have some moment of intellectual awakening through an encounter with a book that they stumble upon. Once I began reading after high school, while fumbling my way through that first semester at a local community college and working in a printing factory doing the most menial tasks imaginable (collating the pages of books manually in the bindery, ironically), I became a reader. Once I began reading, I found myself caught up in the virtuous cycle of seeing myself more and more as a student, as a reader, as someone who thought and was curious about things—which led me to read about them, and so it continued.

Once Jimmy Santiago Baca began reading in the shadowy recesses of his prison cell, there was no way back to the person he had been; so it was for Mike Rose, so it was for Tara Westover, for Frederick Douglass, and for me. Years later, in my first years of teaching, I became friends with Carol Jago, who always asked if I had read the latest New Yorker or some novel by Pat Barker or Toni Morrison, or all the other authors she exposed me to. So I began reading to be able to be part of the conversation with colleagues about books, teaching, and so much more. She was the first of what would become my reading mentors—those people who guide us through the uncharted territory of other lives, worlds, and experiences. But what she really did, as did others along the way in those early years, was make me realize that I wanted to be someone who continued to learn alongside the students I taught, to not lose sight of the pleasure and passion that had led me to want to become an English teacher in the first place.

At the end of “A Personal Prologue,” I explain that when my students ask me what I believe in during those rich conversations we are always hoping to have with our kids, “my answer to this question has always been the same: I believe in education.” But the deeper, more personal answer is that I believe in reading, in that personal journey we must all undertake to become ourselves. As one of my three children said recently in response to my growing passion for fly fishing, “Oh, you know Dad is really into something when he starts reading about it.”

As for HOW I get all that reading done? I think it mostly comes down to curiosity. The other day, I listened to Ezra Klein interview Ta-Naheisi Coates and Nikole Hannah-Jones on his podcast. They talked about the texts they always teach in their classes for the quality of their writing. Coates went on at length about Kathleen Schulz’s essay about earthquakes titled, “The Really Big One”—I had to read that. And when Hannah-Jones talked about one of Coates’s essays, I went back and read that. This was actually a rare occasion when I listened to a podcast, for they are not texts that we can easily use in the classroom nor which I can include in Uncharted Territory. They are wonderful, but as I am trying to challenge my students through complex texts, they are not of much use to me. What are of great use to me and I highly encourage you to check out are audiobooks. Though I have used Audible for many years, Scribd is a tremendous value for teachers and is a bit more like Netflix for readers. There, for less than nine bucks a month, I can read widely—ebooks, audiobooks, magazines, and much more—in the quest for great texts to share with teachers and students in Uncharted Territory.

There are so many other resources I could share and which I find useful, but my point is that it has never been easier to be reading all the time—not out of a sense of obligation but a sense of joy and exploration. At the moment, as I prepare to return to school, I am reading Michael Lewis’s wonderful The Premonition in print in the evenings; listening to Davind Blight’s magnificent Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom as I make my breakfast and tend to various chores around the house; sipping from Phillip Lopate’s delicious The Contemporary American Essay; sneaking in an essay by David Brooks from the latest Atlantic on all the things he now thinks he got wrong about America in his previous books; spending time before returning to school to read and really think about Kate Murphy’s You’re Not Listening, which is so insightful and useful; and, finally, because she remains, after all these years, a good friend and constant guide to books, waiting to begin reading the book Carol Jago most recently said I had to read: The Undocumented Americans, by Karla Cornejo Villivicencio.

By the time I sat down to begin sorting and choosing texts for this newest edition of Uncharted Territory, I had about three times more to choose from than I had room to include. But this is what makes Uncharted a special book to me: I am always reading what seems interesting to me but would also be of interest and use to you and all my fellow English teachers. Even now, with this second edition finished and coming out, I am already on the hunt for new pieces for the next edition that will come out years from now. In the meantime, you will find me here, in this blog, thinking about the challenges we face together and doing my best to share what I think will help you navigate your way through them in the year ahead.

#education#reading#reading recommendations#frederick douglass#carol jago#ta nehisi coates#ezra klein#michael lewis#tara westover#jimmy santiago baca#kate murphy#karla cornejo villivicencio#david brooks#nikole hannah jones#in the classroom: preparation

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Past Is Never Forgotten

At first glance, it seems sad and strange to advise a young person such as yourself to read obituaries. Yet, what are obituaries but the stories of the lives we all hope to live—the things we accomplish, the people we love, the interests we develop. As the New York Times notes, around 155,000 people die each day in the United States, their lives largely going unnoticed in the newspapers. But, in an effort to create a more complete and fair record of the lives of noteworthy people, the New York Times launched a collection titled Overlooked, in which they write the obituaries of people whose deaths went unmarked but who, as time has passed, have grown in importance. The series focuses particularly on women and people of color, such as Henrietta Lacks, the subject of Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, who never had an obituary written about her, despite her importance to modern medicine and science.

Questions

1. First, scroll through the different obituaries in the Overlooked series, searching for one about a person you are reading about or whose life intrigues you.

2. After reading the obituary, identify and discuss what seem to you to be the most salient details and accomplishments of this person’s life.

3. What is the argument the writer of the obituary you chose is making regarding the meaning and importance of this person who was “overlooked”?

4. As a genre, obituaries offer an opportunity to honor and celebrate the life someone lived, the contributions they made, the lives they touched. Write a reflection about someone you either knew (a family member, friend, mentor) or whose life you have always admired (a musician, actor, leader, inventor).

#Identity#Education#Success#Decisions#Credo#Relationships#Power#Freedom#Memoirs and Personal Essays#Literacy Narrative#Argument#Cultural Analysis#Text#Images#A Lesson for the Dying#The Absolute True Diary of a Part-Time Indian#Invisible Man#Jane Eyre#Fences#Alice Walker#Love Medicine#Their Eyes Were Watching God

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Art of the Struggle

The artist Charles White offers a compelling visual record of the story of African Americans in the United States in the 20th century. Having lived through many of the events of the modern era, White chronicled the political and cultural history through a diverse array of portraits of people central to the country’s struggles. In Charles White: A Retrospective, we see a major artist trying to create social change through his art. In the exhibit, you will find images, text, and video examining White’s work and his response to the times during which he lived.

Questions

1. First, watch one or both of the videos that provide background about Charles White’s work. What are the key themes and impressions that emerge about White and his art?

2. View a number of White’s paintings from the exhibit. What elements of style, subject, and treatment run through the artworks you viewed? What do you think he is trying to say or accomplish through these paintings or drawings? How does his style support his artistic purpose?

3. What connections can you make between the work in this exhibit and works of literature you have read in your English class? Be specific about the common subject they address and compare their treatment of it.

#credo#identity#relationships#power#profiles of people and places#cultural analysis#visual analysis#audio#video#image#text#Invisible Man#their eyes were watching god#The Other Wes Moore#Fences#Black Boy#The Color Purple#The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks#Beloved#The Bluest Eye#Between the World and Me#My Beautiful Struggle

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Only You Can Write Your Story

We hear it said or say it to ourselves all the time: You are the author of your own story. But what do we mean when we say this? In this essay by Steph Curry’s mother when Steph was thirteen, emphasizes that “NO ONE gets to write your story but you.” Here we have one of the all-time greatest athletes talking about how pathetic he was when he was young, how underrated he was—even by himself. Yet, this is the very source of his power if you read what he says here. It is “feeling underrated” that fuels his success, keeps that chip on his shoulder, keeps him from ever believing he is as good as he is.

Questions

1. Explain why Steph Curry titled his essay “Underrated”—and why this is the perfect title. Cite the essay to support and illustrate your ideas as needed.

2. Reread Steph Curry’s mother’s comments from that night in the Holiday Inn in Tennessee when Steph was thirteen. Discuss what his mother says and why Steph thinks it was “the most important talk of [his] entire life.”

3. Examine Curry’s style in this essay. He does some interesting things with the Twitter posts throughout the essay, and makes some great moves that create a relatable voice in the writing. What are some of the moves you notice and what do they contribute to the writing? How do they help him to achieve his essay's purpose?

4. Explain what Curry means when he says one should “figure out how to harness” the feeling of being underrated. How does this idea explain his success, and how might it apply to you?

#identity#decisions#education#success#credo#memoirs and personal essays#profiles of people and places#literacy and narratives#text#Into The Wild#A Portrait of the Artist as A Young Man#The Other Wes Moore#THE ABSOLUTE TRUE DIARY OF A PART-TIME INDIAN#The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao#the catcher in the rye#the house on mango street#invisible man

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Becoming Yourself

In the early years of our adult lives, we have so much to learn when it comes to work, relationships, and our own identity apart from our past. Few people have had to grapple with such questions more than former first lady Michelle Obama. In the years before her husband became the president, Michelle Obama faced the same dilemmas most of us, especially women, encounter; however, as first lady, she has worked through challenges that are unique to her but yielded lessons that apply to us all. Though the text included here is not challenging, the ideas and examples offer important advice.

Questions

1. Summarize how Michelle Obama learned to be true to herself, according to this interview.

2. Identify one common theme that runs through the four lessons that Michelle Obama learned. Explain why that theme is important.

3. How does this interview reflect Michelle Obama's commitment to connect with and help as many people, especially women, as possible? How do the language, tone, and anecdotes help her achieve her goal of “serving society”?

#credo#identity#education#relationships#success#profiles of people and places#memoirs and personal essays#text#invisible man#their eyes were watching god#The Other Wes Moore#fences#Persepolis#In the Time of the Butterflies#scarlet letter#the immortal life of henrietta lacks#the awakening#hamlet

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What Is America to You?

America seems to be one of the few countries always asking what it is, what it could be. It is a country whose Constitution begins by insisting it is a work-in-progress: “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union . . . ." In other words, the very idea that it could be improved is part of its founding. As with so many Americans, it is a country intent on creating and re-creating itself as time passes. In his poem “Let America Be America Again,” Langston Hughes challenges us all, as individuals and as a nation, to “let America be America again.” What does that mean and how do we go about accomplishing such a goal?

Questions

1. Explain the argument behind the title—“Let America Be America Again.” What is Hughes saying about America? What is motivating him to make this argument? Why does Hughes choose to use the word "again"?

2. Throughout the poem, Hughes uses repetition. What is he trying to accomplish through this use of repetition? What effect does his use of repetition have on the meaning of the poem when you hear it performed aloud by Danez Smith?

3. What do you think it would mean for “America to be America again”? And how do you think we could make that happen?

#identity#power#relationship#freedom#argument#poetry#cultural analysis#profiles of people and places#image#video

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Power of Words—and Coaches

We all need coaches, even if we are not athletes. We find these people in many places—where we go to school, where we worship, where we play sports—but they all serve the same purpose: to show us who we are and what we can accomplish. Some coaches see things in us that we never knew were there. Some coaches act as parents to us at certain times in our lives. In this short documentary titled Lettermen, we see just what this sort of relationship can accomplish and how one coach used writing to accomplish it.

Questions

Summarize the story about the “Lettermen” and their experience with Coach Matsumoto. Be sure to include in your summary a discussion of the letters and their role in the story.

How is the documentary organized—and to what end? In other words, how did the director structure the story and why did he organize it that way?

How would you characterize the relationship between Coach Matsumoto and his players? How does the nature of that relationship explain the event at the end and how the young men respond to Coach Matsumoto’s news?

Discuss either the relationship between a coach and his or her players in general or tell the story of your own experience with such people in the context of sports, dance, music, academics, or other areas where you had a “coach.”

#credo#identity#education#success#relationships#profiles of people and places#reportage#cultural analysis#literacy and narratives#video#The Other Wes Moore#Into The Wild#Americanah#Frankenstein#Catcher in the Rye#To Kill a Mockingbird#A Lesson Before Dying#Stitches#The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Universe Is His Classroom

Poets have written that we should try to “see the world in a grain of sand.” Other people have declared “the world is your classroom.” But what about going to live in space for 500 days on the International Space Station as an astronaut, while back home your twin brother is subjected to the same tests and experiments you are doing up in space? This is the challenge that Scott Kelly (and, back on earth, his twin brother, Mark) took on. But what lessons are there to learn from such an adventure?

Questions

After reading this excerpt from Scott Kelly’s memoir in which he details the many lessons he learned over the course of the 500 days he spent in space, outline what the lessons have in common?

How would you describe Kelly’s style of writing? Given that he is an astronaut and writing for a general audience, why do you think he would choose to write this memoir in the style and voice he did?

Which of the many lessons Kelly learned is most interesting or important to you? Explain why, and discuss the implications of that lesson as they apply to you or people in general.

#education#success#credo#relationships#memoirs and narratives#reportage#text#The Other Wes Moore#Brave New World#Into The Wild#Siddhartha#The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao#Persepolis#Fahrenheit 451#Walden

1 note

·

View note