Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

something i never understood about the ahs fandom: when i was like 14 on tumblr… everyone was out here romanticizing tate and violet. i was expecting this super grungy epic love story and then i watched it and my brain just went ???

like… this man literally:

ra*ped violet's smom (aka fathered her half-brother)

is a whole mass mu*rderer

gaslight violet into “loving” him

and y’all were out here putting them on your blogs with lana del rey lyrics over black-and-white gifs??? this relationship is so toxic omg.

and don’t even get me started on how no one took kit walker seriously in season 2. my boy was literally so cute and soft, just trying to hustle between his two wives and have a quiet life 😭 the way tumblr ignored him because he wasn’t a sad emo boy with a hoodie… unforgivable.

justice for kit walker forever.

#alternative#rotcore#southern gothic#dark aesthetic#ahs asylum#gothic#ahs fandom#ahs murder house#ahs tate#american horror story#tate langdon#tate and violet#kit walker#american horror murder house#mine#american horror coven#evan peters#film essay#film#ryan murphy#ethel cain

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

There’s a theory in psychology called Object Relations, which says that a child’s psyche is shaped based on their early experiences with their parents. Later on, the child’s expectations from the outside world are also influenced by these early relationships with mom and dad.

For example, if a child’s parents suddenly shower them with affection and then abruptly withdraw it, that child will grow up expecting that anyone who loves them will eventually leave them.

This theory was later expanded to cover other areas too. It turned out that it’s not just limited to parents. There’s a general internalization process in all humans where their first experiences of a certain kind of relationship become embedded in their psyche. In a way, this forms part of that person’s “self.”

It’s tied to the whole concept of being haunted — like in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, The Haunting of Bly Manor, or books like Beloved. We don’t analyze new people who enter our lives purely for who they are. We always go back to our past experiences — our heartbreaks, sorrows, and patterns — and then decide how we want to deal with people and relationships.

In a way, our relationships are haunted by many people from our past. And this isn’t just some superficial pop-psychology theory. We truly can’t erase our past experiences, whether good or bad, from who we are. In the end, those experiences become part of us and affect how we relate to others. And that, in itself, can feel even scarier than being haunted by ghosts.

#alternative#rotcore#southern gothic#dark aesthetic#dark art#gothic#daughter of cain#ethel cain#aesthetic#nicole dollanganger#tumblr girls#poem#spotify#inspired by ethel cain#mine#my essays#film essay#psychology#film#willoughby tucker#willoughby tucker i’ll always love you#phobe bridgers#i know the end

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

When we think about leaving childhood behind, we usually place ourselves as the one saying goodbye — to soft memories, safe spaces, and a time of innocence. We feel nostalgic. We long for it.

But what if it wasn’t just a one-sided goodbye?

What if childhood, too, had a heart — and missed us in return?

This tender, haunting idea is brought to life beautifully in Pixar’s Toy Story films — a world where toys are more than just objects. They are alive, loyal, feeling beings. But even more than that, they are living symbols of the moments, memories, and parts of ourselves we’ve left behind.

In Toy Story 3, Andy is all grown up and about to leave for college. His toys — Woody, Buzz, Jessie, and the rest — have spent years tucked away in a chest, forgotten. But when he opens that box, he pauses. He holds them gently, like he’s cradling a part of himself he didn’t realize he still missed.

The scene hits hard, because we realize:

Our childhood doesn’t just vanish — it waits. It stays. It still loves us.

The toys in Toy Story aren’t just characters. They’re representations of the inner child — the imaginative, loyal, hopeful part of us that never truly disappears. Woody, for example, stands for comfort, safety, and constancy. Buzz is the dreamer in us, the part that reached for the stars.

When we grow up, those voices fade. But Toy Story suggests: They’re never completely gone.

And so Woody, over and over again throughout the films, asks one painful question:

"What’s my purpose if no one plays with me anymore?"

It’s the same question our memories ask us:

"If you let go of me, do I still mean anything to you?"

We often think growing up is about us moving on. But what if the past has its own grief too?

What if the childhood we left behind still waits by the window, wondering if we’ll come back?

This way of thinking transforms nostalgia from a passive ache into something reciprocal. It’s not just that we remember our childhood — our childhood remembers us too.

When Andy gives his toys to Bonnie, it’s one of the most emotionally resonant scenes in animation. He says each of their names with love. When it’s time to give Woody away, he hesitates — and then finally lets go.

But this moment isn’t just a farewell.

It’s a resurrection. A passing of the flame.

Andy realizes that locking his toys in a box won’t preserve his childhood. He has to let them live again.

That’s the only way that part of him can continue.

The truth is, we never really leave childhood behind.

The toys, the laughter, the imaginary worlds — they’re still alive somewhere within us. Even if we can’t hear them anymore, they might still be whispering.

And maybe, if you glance out the window of your life one day,

you’ll see your childhood waving back at you — still waiting, still loving.

#alternative#rotcore#southern gothic#dark aesthetic#dark art#gothic#early 2000s#2000s nostalgia#toy story#movie review#nostalgia#2000s kid#mitski#personal#mine#my essays#daughter of cain#film#inspired by ethel cain#2000s#ethel cain#aesthetic#Spotify

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is a haunting clarity in Laura Gilpin’s poem The Two-Headed Calf — the quiet, devastating realization that something beautiful and alive is already doomed. It is not the death that shocks us, but the tenderness of the moment before it: the calf, lying in the field under the moonlight, unaware of what tomorrow will take. In just a few lines, Gilpin captures the fragility of life, and the profound, aching gift of being alive just before the world turns.

When I was eleven, I had my own two-headed calf moment.

It came not in a field, but in a classroom, when the topic of puberty was introduced. The adults spoke clinically, with diagrams and terms — “hormones,” “change,” “growing up.” But beneath their words, I heard something else: that everything I knew was about to vanish. That I would no longer be a little girl. That my parents would grow older, that my friendships would scatter, that my childhood home — the world as I knew it — would begin to dissolve.

I remember crying in my father’s arms that night for almost half an hour. It wasn’t a tantrum. It was mourning — mourning something that hadn’t even left yet, but I already knew would. I couldn’t grasp how people carried on so normally, knowing that the things they loved were temporary. That they would wake up one day and everything would be different, and there’d be no going back.

My father didn’t lie to me. He didn’t offer comfort in the form of denial. Instead, he told me the truth: that time can’t be stopped, that I would turn thirteen, sixteen, twenty-five. That life would bend and break and push in ways I couldn’t yet imagine. But then he said something else, something that has stayed with me like a thread in my chest:

"Right now, you are still eleven. This moment is still yours."

That moment of stillness — the recognition of now — is where my experience and Gilpin’s poem intertwine. The two-headed calf does not know it is a “freak,” does not know it will be found, studied, and pitied. All it knows is the wind in the grass, the moon rising over the orchard, and the strange magic of seeing twice as many stars. Its tragedy is real — but so is its wonder. And the wonder does not cancel the sadness. Nor does the sadness erase the beauty.

To be eleven and realize the world will end — not through fire or disaster, but slowly, through ordinary growing — is a kind of awakening most people experience in private, and too early. It is the moment when you stop simply being, and begin to understand loss. And yet, that night, in my father’s arms, I was still held in the warmth of the present. I had not yet become what I feared. I was still the girl who looked at people’s eyes and sensed their sadness before they even spoke.

Like the calf, I had one perfect night before the museum — before the forgetting, the aging, the changing. That night was mine. It didn’t save me from growing up. But it taught me how to hold time gently before it slips away.

#alternative#rotcore#southern gothic#dark aesthetic#dark poetry#gothic#dark art#daughter of cain#ethel cain#two headed calf#nicole dollanganger#my essays#poem#aesthetic#tumblr girls#spotify#preachers daughter#laura gilpin#freak of nature#love the unloved#inspired by ethel cain#i bet on losing dogs#mitski

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

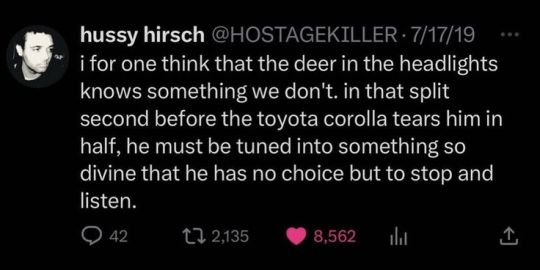

One of the cute little things I’ve always noticed is how, in Celtic and Arthurian mythology, deer symbolize transition and transformation into another world.

And I keep thinking about this idea—what if deer experience a kind of apotheosis right before getting hit by a car?

Because it’s such a recurring motif in media: right before something horrific happens, a car hits a deer.

It always reads like an omen—a sign that everything’s about to fall apart for the character.

The moment feels like an impossible movement: the deer sees the light, but then it’s as if it can’t move.

Biological reasons aside, what matters is how we interpret it as the audience.

Usually the character sees the signs too, but they’re somehow powerless to stop what’s coming.

And I’ve always had this personal theory in the back of my mind:

What if it’s not about shock or paralysis?

What if the deer is a Christ-like figure, embracing death as a form of ascension?

Because light is also a metaphor for God.

#alternative#rotcore#southern gothic#dark aesthetic#dark art#gothic#thought daughter#essay writing#deergirl#daughter of cain#ethel cain#nicole dollanganger#tumblr girls#poem#mine#my essays#writing#film#inspired by ethel cain#david lynch#deer#spotify

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

even the iron still fears the rot

#aesthetic#ethel cain#daughter of cain#gothic#poem#nicole dollanganger#rotcore#southern gothic#tumblr girls#art#ptolemaea#tw blood

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

˖ ݁𖥔 ݁˖ 𐙚 ˖ ݁𖥔 ݁˖ Kit Walker the things I'd for u ˖ ݁𖥔 ݁˖ 𐙚 ˖ ݁𖥔 ݁˖

#evan peters#ahs fandom#ahs asylum#american horror story#kit walker#music to watch boys to#lana is god#lana del rey#Spotify

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to make vampire girls:

It all starts in the swollen throats, choked with memories they never tell to any ghost. Mom doesn’t brush their hair anymore. Dad doesn’t tell stories.

They turn eleven and pretend that they don’t see the signs.

But they can't ignore that long.

Too curious for their own good.

Once they find out their loved one's secrets, they'll be bound to be the last ones standing on Earth.

And just like that the places that used to feel like home are now just big crawl spaces.

They'll tell another lie, and they'll buy themselves five more minutes of feeling.

Their friends disappear mysteriously one by one.

And one night, at fourteen, they wake up from chewing on their own wrists.

They all say they’ve changed. but isn't that what they say about all teenagers?

They stay up at night, freezing to their core—but it’s not the open windows.

It’s something inside that’s gone terribly rotten. And there’s no use in digesting it.

Mom says "it’s the food".

But one time they get so mad at their best friend they forget that they're not allowed to bite to her.

So they next time they see her face it's on the missing papers all over the walls of the town.

There’s this hunger that never ends, not even when they stop eating.

Mom says their legs are getting fat…

But what does she know about calories gained from the blood of the loved ones?

Maybe she hears the whispers that they're chanting while they're asleep

“You never should have given birth to someone you don't know their cravings"

So many cuts. So many scars.

And they’re still not even eighteen.

A long road trip, and they don’t even know how or when they have turned to this thing.

#alternative#rotcore#southern gothic#photography#morute#poem#vampire aesthetic#girl writer#ethel cain#daughter of cain#gothic#aesthetic#poetry#jennifers body#sadgirl

3 notes

·

View notes