mostly stuff involving sabres, horses, bayonets and muskets

Last active 60 minutes ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

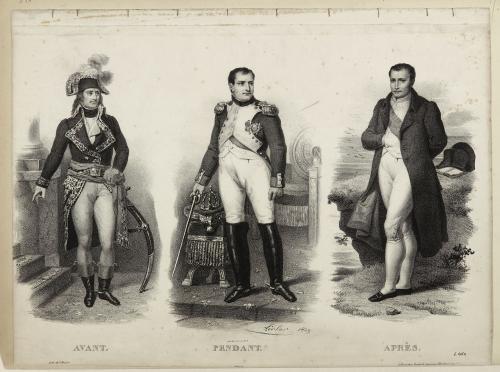

Photo

Napoleon at three moments of his life: the Egyptian campaign, the height of the Empire, and St. Helena. Carnavalet museum, Paris

60 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna // July 19, 2017

63K notes

·

View notes

Photo

French Hussar and Peasant Girl, 1810’s

I’ve been wanting to practice some 2D painting for a while, here’s the first of what I hope will be a number of historically themed pieces. Inspired by 19th century artists and my contemporary hero of historical military painting, Spanish master Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau. The rider is a Napoleonic French Hussar of the 11th regiment.

https://www.artstation.com/artwork/GXy8xV?fbclid=IwAR1MCaGls2sQkye16ItT4OdB0wv2Fc6K5lCViNPF4o5hqogS4KCr-582aAs

535 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Dutch Klewang (Maréchaussée sabel)

The Dutch klewang is a pretty famous type of sword and antique examples are often encountered. They were in use from before 1898 and until after WW2 and formed the basis for the US M1917 naval cutlass. Very useful thread with more detail: http://www.vikingsword.com/vb/showthr…

34 notes

·

View notes

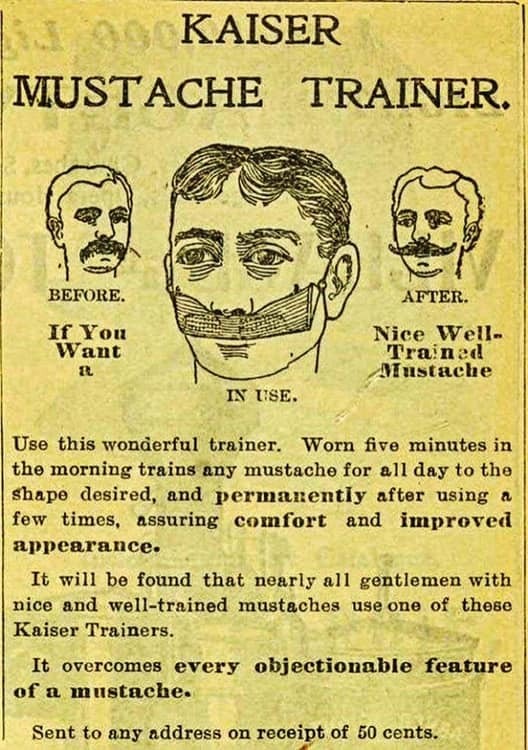

Text

Definitely something worth buying!

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Victory at Bermuda, the Capture of the HMS Dominica by American Privateer Decatur, by Maarten Platje 2018

Afficher davantage

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Russian Don cavalry horse in traditional costume

417 notes

·

View notes

Photo

WWI. A photo postcard showing Troopers of The City of London Yeomanry (Rough Riders) performing sword drill.

124 notes

·

View notes

Photo

British Military Swordsmanship on Foot, 1796-1821

Check out this incredible image by Nick Thomas of the Academy of Historical Fencing!

Nick says of the image;

“I’d like to see these weapons seen more as the family they are, and so here is a composite image created entirely from contemporary artwork of the period.”

131 notes

·

View notes

Link

By /u/400-Rabbits

The Spanish Conquistadors regularly expressed their respect of both native weaponry and armor. Bernal Díaz del Castillo gives us our most vivid descriptions of combat when engaging with Mesoamerican forces. For instance, this passage from the second time the Spanish and Tlaxcalans clashed:

When, therefore, the attack commenced, a real shower of arrows and stones was poured upon us; the whole ground was immediately covered with heaps of lances, whose points were provided with two edges, so very sharp that they pierced through every species of cuirass, and were particularly dangerous to the lower part of the body, which was in no way protected.

There’s really two aspects to both native and foreign arms and armor being demonstrated here. One thing to note is that the Spanish who accompanied Cortés were very rarely wearing anything resembling full-body steel armor. Spanish accounts confirm that the “infantry” would have had at least a sword and shield, but armament beyond that was up to the individual soldier to supply for themselves. The most common pieces of armor mentioned are helmets, gorgets, and cuirasses, though the presence of these were not universal to all soldiers, nor did the initial arms and armor of the Spanish always last through the rigors of the campaign. To quote Díaz del Castillo again, he remarks that when a group was traveling back to the Gulf coast to confront Narvaez:

We were altogether in want of defensive armour, and on that night many of us would have given all we possessed for a cuirass, helmet, or steel gorget.

Even the steel cuirasses of the Spanish were not always protection from Mesoamerican weaponry, as the first passage quoted indicates. Díaz del Castillo himself writes about one instance where his steel cuirass was pierced by an atl-atl dart, and he was saved from serious injury only by the cotton armor he had taken to wearing underneath it. Indeed, the Spanish often took to adopting some form of the quilted cotton ichcahuipilli, sometimes paired with a Spanish cuirass but sometimes not, because of the both the protection and comfort it afforded.

Whatever steel armor the Spanish could afford for themselves did provide a more effective defense, but rarely did it protect the whole body. Ross Hassig notes, in his Mexico and the Spanish Conquest:

Clubs and swords had their effect, but Spanish steel armor was proof against most Indian projectile, except perhaps darts cast from very close range. Indeed, Spanish wounds were typically limited to the limbs, face, neck, and other vulnerable areas unprotected by armor…

Those unprotected areas could find themselves very vulnerable given the rain of arrows that accompanied assaults, and reports of injuries and deaths from volleys of arrows (and sling stones) are not uncommon in Conquistador accounts. Hassig, however, points to an advantage in the missile weapons of the Spanish, noting their crossbows and harquebuses were most effective at close range, with the inaccurate latter weapon even more effective against closely masses troops, as Mesoamerican military doctrine at the time tended to provide. Nevertheless, we see native forces sometimes retreating back to a point where the guns of the Spanish were largely ineffective, but that the bows of the indigenous archers could rain arrows down on the Spanish at a much greater rate then the Spanish crossbows could reply. If the Spanish were unlucky, as in the case of the Cordoba expedition in a Maya town, the arrow/sling barrage could keep them pinned down until more Maya forces arrived and swamped the Spanish, resulting in the loss of about 50 of the 100 Spanish soldiers, including Cordoba himself later dying from injuries.

If the Spanish were lucky, they could maintain a defensive formation and withdraw, using cavalry charges or artillery to break the lines of the opposing force. These are the tactics Cortés used in his clashes with the Tlaxcalans. No matter the defensive advantage of steel armor or the offensive advantages of crossbows, guns, and artillery on massed troops, the Spanish quite often found themselves having to maintain a defensive position and execute strategic withdrawals in the face of more numerous and better supplied foes who were quite capable of enacting grievous harm on them. Only with the alliance with native groups would the Spanish (and their allies) see a distinct military advantage. To quote Hassig again:

Thus, while the Spanish enjoyed greater firepower, which prevented their enemies from engaging them in organized formations, and although they could disrupt the enemy fron much more easily than could Mesoamerican armies, they were too few to exploit these breaches fully. If they joined forces with large Indian armies, however, these allies could exploit the breaches created by the Spaniards, while maintaining the integrity of their own units, because other Indian armies lacked the Spanish edge in arms and armor. Together they could wreak havoc on the enemy.

Ultimately, if we look at the clashes between Spanish and indigenous groups in Mesoamerica, neither guns, steel, or horses (or germs, for that matter), were decisive. While it is tempting to crudely lump the Aztecs into the “Stone Age,” while putting the Spanish further along some imaginary and arbitrary tech tree, we must keep in mind that the macuahuitl and tepoztopilli were not “crude” weapons, but the result of centuries of refinement and practical tests in Mesoamerican warfare. The Spanish rightly feared and respected those weapons. So to were the tactics of the Aztecs refined for the opponents they faced. Prior to the Spanish, the Aztecs had enjoyed a century of almost ubiquitous military victories, and though we can absolutely see how their tactics were thrown for stumble by the addition of never before seen weaponry like artillery and cavalry, particularly at early encounters like Otumba, this was an intelligent and adaptive war machine. By the time the Spanish licked their wounds from La Noche Triste and returned in force with the Tlaxcalans, the Aztecs had autochthonously invented cavalry counter-measures with pike-like spears and ensuring the chosen field of battle with marshy or strewn with stones. They had adopted tactics to blunt the guns and artillery of the Spanish with breastworks and zig-zag maneuvers.

Bottom line, both the Spanish and the Aztecs respected each other as deadly opponents.

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Two non-commisioned officers of the Royal Dutch military constibulary (Koninklijke Nederlandse Marechaussee) in service dress with and without greatcoat around 1929. The mounted corporal on the left is wearing the Dutch cavalry sword M.1876. The sergeant on foot on the right is wearing the carbine M95 and the klewang-Marechaussee M.1913. This model klewang is recognisable for instance by its chromed steel scabbard and chromed blade. It is still in use today only as a ceremonial weapon.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Harry Pendrel Brittain, Army Service Corps Trumpeter, aged 15. 1914

Army Service Corps Trumpeter Harry Pendrel Brittain aged 15. Brittain joined the Army Service Corps in 1913 and this photograph was taken just before he, and his horse Grace, left for the Front in 1914. Although Grace was killed in action, Harry served through the War and died in the Cambridge Military Hospital at Aldershot in 1929 aged 31.

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

@vythodias

I bought it from Kult of athena. It goes for $183,95.

It's however not made by Cold Steel, but Universal Swords. It weighs 816 grammes or 1 lb 12.8 oz and the point of balance is about 17ish centimetres away from the hilt, which is about 6.7". It does have distal taper, starting off at 7mm (0.275") near the hilt to 4.15mm (0.163") at the tip

For a spadroon, it feels very beefy in the blade. I think it'd be a pretty decent cutter. I'm saying "think" because I haven't really cut with it yet.

I couldn't help myself and I just had to try thrusting on some cardboard boxes, which went very smoothly and it was really easy. The fine point (spear point tip) makes thrusting no problem at all!

I suggest you buy the Cold Steel version though, as it seems to be better balanced with the point of balance being about 5"

Guess what came in the mail today?

It’s the five ball spadroon by Universal swords!

I don’t know what it is about spadroons, but I’ve always loved them and owning one now made me appreciate them even more.

Historically speaking, spadroons have been in use for a long time. They’re a cut and thrust sword and models like this reproduction would have been used by French, American and British naval officers during the late 18th century.

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guess what came in the mail today?

It's the five ball spadroon by Universal swords!

I don't know what it is about spadroons, but I've always loved them and owning one now made me appreciate them even more.

Historically speaking, spadroons have been in use for a long time. They're a cut and thrust sword and models like this reproduction would have been used by French, American and British naval officers during the late 18th century.

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A selection of Zulu weapons actually used in 1879 including a regimental shield in the colours of the uThulwana regiment and an Enfield percussion rifle used at Hlobane and Khambula.

676 notes

·

View notes