Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Chocolate Consumption in Europe and Colonial America

In 1492, the world was fundamentally changed with Christopher Columbus’ discovery of the Americas. With this discovery came a wide exchange of diseases, flora, fauna, people, and most relevant to this blog entry, food. Chocolate first arrived in Europe in 1544 as gifts from the Maya; the first official shipment of cacao to Europe was in 1585. With cacao’s introduction came a crisis of identity and morality for Europeans; Europeans viewed chocolate as primitive or as sinful. In order to consume chocolate, Europeans would use a number of justifications. The integration of chocolate into European societies is a prime example of the processes of colonization and what happens to material objects after they’re appropriated by colonizers.

Europeans would first be exposed to chocolate via the conquistadores’ interactions with the Mexica and the Maya, who revered chocolate as an elite, valuable good. Explorers then returned to Europe with chocolate; chocolate was still seen as an elite, revered good, but without the ritualistic and religious value that it held among the Mexica and Maya. Cacao first arrived in Europe in 1544, with a delegation of Maya natives; during this time, chocolate was an exotic luxury. As time went on, chocolate became more common, and by the 17th century, chocolate and the tools used in its consumption were regularly shipped to Europe. Initially, chocolate was consumed in much the same way it was in the Americas. It was nearly a century since its discovery before Spain introduced chocolate to the rest of Europe. The first evidence of chocolate consumption outside of Spain comes from Tuscany; it then spread through France to Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. In the U.K, chocolate grew in the second half of the 17th century, appearing in cookbooks in the 1650s. Although chocolate was very expensive in the U.K, it was more accessible than it was on the rest of the continent; the first chocolate house was opened in London, and chocolate became an established part of the 18th century breakfast in France and England. Over the course of the 18th century, chocolate consumption in Europe grew from 2 million to 18 million pounds.

To be accepted by European society, chocolate had to be changed. The first transmutation of chocolate was that Europeans would only drink it hot; the second was the addition of sugar or honey, and the third was spices more familiar to Europeans, like cinnamon and black pepper. To create the foam, Spaniards used tools called molinillos. Most importantly, Europeans stripped all of the spiritual meaning chocolate held, and it was primarily a recreational food.

Initially, chocolate acted as a status symbol due to its expense and labor intensive production; consuming chocolate implied that one had the means to get chocolate and a large amount of leisure time. Europeans internalized the association between chocolate and nobility made by the Mexica, but eliminated the spiritual meanings from it; chocolate was the official status of wealth in Baroque Europe. Chocolate didn’t become widely accessible for the lower classes until around the Industrial Revolution with the creation of large chocolate manufacturers.

However, as chocolate became an increasingly popular leisure food, the Church became concerned. The Church associated chocolate with sinful habits and the devil. Sins associated with chocolate included gluttony, lust, and greed. There was a particular connection between gluttony and lust with women who consumed chocolate. The Church also believed women used chocolate to control men; chocolate became associated with female disorder including witchcraft, murder, and sorcery.

Chocolate consumption was also frowned upon because it was believed to make European consumers “go native”. One story tells of women in Chiapas that stopped attending mass after a bishop had prohibited chocolate consumption at church. The women stopped going, and the bishop passed away; according to this anecdote, one of the women had been sending the bishop poisoned chocolate every day. This anecdote offered “evidence” of the addictive nature of chocolate. This anecdote also points to the fear of Europeans losing the cultural identity that had brought them to power in the first place.

In order to make chocolate consumption more socially acceptable, Europeans began categorizing chocolate as medicine. However, before Europeans could adopt chocolate as a medicine, they first had to integrate it into their understanding of medicine, which was the theory of the 4 humors. The idea at the time was that the human body had a balance of 4 substances, or humors: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. The quality of these humors were dry or wet, and cold or hot; for example, blood was hot and moist. Different foods were thought to contain different traits that would correlate to these attributes. Chocolate would eventually be made to fit into the four humors theory. In the 1570s, Francisco Hernandez stated that cacao was cold and moist, and in the 1620s, Santiago Turices distinguished that chocolate was dry and hot. Chocolate was portrayed as a near cure all in a 1631 medical treatise; chocolate was supposed to cure coughs, inflammation, and obstruction, aid in digestion, clean one’s teeth, and induce conceptions and easier births in women. With this medical treatise, there was irrefutable support for chocolate, therefore permitting its consumption and making the native food acceptable for Europeans. This treatise illustrates a large shift in the view of chocolate, from an exotic luxury, to a sinful commodity, to a widely accepted medicine.

The introduction of cacao created an existential and morality crisis for Europeans. Due to the relationship between Europeans and the indigenous populations of the Americas, chocolate was viewed as immoral and primitive. Once chocolate consumption gained popularity in Europe, Europeans had to wrestle with the fear of losing their cultures that made them globally dominant, and in order to consume chocolate, Europeans had to create an acceptable reason for it. Chocolate is a great example of what happens to a good that is appropriated by colonizers. It is stripped from its cultural context, viewed negatively by the colonizing culture due to societal fears held about the colonized culture, and then eventually made acceptable and integrated into the colonizing culture through various justifications. The physical good is also exoticized and made into a status symbol.

Works Cited

Juarez-Dappe, Patricia. “Chocolate in colonial times: consumption.” YouTube, August 27, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z79RNMcJ5cY

0 notes

Text

Chocolate Encounters

When Christopher Columbus accidentally discovered the Americas in 1492, a new world was opened up, literally. Only two years later, Spain and Portugal had divided the Western Hemisphere between each other with the Treaty of Tordesillas. By the turn of the 16th century, the Columbian Exchange, as well as colonization, was fully underway. Using chocolate as a lens of study, one is able to examine the nature of the Columbian Exchange, as well as the effect it had on the natives and their European colonizers. Even though Europeans colonized the indigenous peoples of Central and South America, Europeans were themselves colonized by the natives. Europeans were colonized by natives through taste, with the adoption of chocolate being a good example.

As stated above, while Europeans were colonizing the natives of the Americas, Europeans themselves were colonized through taste. However, before discussing the colonization of European taste by natives, we must first discuss the context of European conquest of the Americas, as well as the Columbian exchange. The conquest of the Americas was the result of a series of long term developments in Europe, the two most important being the Spanish Reconquista and commercial expansion. The Reconquista was a long lasting fight between the Iberians and the Moors who had invaded the peninsula in the 8th century, and the commercial expansion is when Spain and Portugal sought to expand trade by gaining access to spices in the east. Following the discovery of the Americas, conquistadors came to the New World for God, glory, and gold. The conquest of the Americas had profound consequences; there was demographic decline, the imposition of new authorities and economic systems, and the development of the castas system, as well as massive biological changes. The biggest effect of the conquest was the Columbian Exchange, the widespread transfer of plants, animals, and germs between the Americas, West Africa, Europe, and Asia during the 15th and 16th centuries. According to historian Alfred Cosby, who coined the term “Columbian Exchange” in the 1970s, it was nature that produced the most destructive and creative processes that refashioned the New World after the conquest; he argued that the profound ecological transformations that overtook the World in the 16th century was the single biggest revolution in history caused by human agency. Organisms of all types were transferred to and from the Old and New Worlds, with cacao being one of them.

Europeans first “discovered” cacao in 1502 with Ferdinand Columbus, Christopher Columbus’ son. While in Guanaja, Ferdindand observed cherished almonds that were traded in a similar way to currency. “The Spaniards captured a trading canoe that included cotton, garments, war clubs, axes and bells, and what they thought were almonds; when some beans fell to the bottom of a canoe, Ferdinand described the men as scrambling to retrieve them as if ‘one eye had fallen out’”. These beans, or “almonds” were believed to be valueless by the Europeans.

Europeans would not realize what cacao was until 1519. When Hernán Cortés was staying in Tenochtitlan, chocolate was one of beverages included at banquets organized by the emperor for his guests. Cortés found the drink bitter, strange, and almost undrinkable. However, Cortés quickly realized that cacao beans were used as currency and tribute; in a letter to king Charles of Spain, Cortés described cacao as “a fruit, like an almond, which they grind, and hold to be of such value that they use it as money”. After discovering the value of cacao, Cortés was quick to establish cacao plantations; cacao was one of the first cash crops produced in the new world, possibly even before sugar.

The first documentation of cacao in Europe was in 1544 with a delegation of Maya natives in Spain; this delegation brought gifts, with chocolate and cacao being among them. Chocolate was exotic and a luxury. 40 years later, in 1585, the first official shipment of cacao would arrive in Europe. During this early period of the 16th and 17th centuries, chocolate was consumed in Europe in much the same way it was in the Americas, that being a liquid form with the traditional species of vanilla, chili, and ear flower. In order to counteract the bitterness, the Spaniards added sugar or honey. The initial response to chocolate in Europe was mixed. The Italian historian Girolamo Benzoni described chocolate as “ a drink for pigs” in 1575; however, 40 years later, Jesuit José de Acosta wrote that “chocolate disgusts those who are not used to it, for it has a foam on top, or a scum like bubbling, and the Spanish men, and even more, the Spanish women, are becoming addicted to it here.”

During the early years of chocolate consumption in Europe, many Europeans were disgusted by it; for these Europeans, adopting the habit of consuming chocolate was the equivalent of becoming “uncivilized” or “going native”. As seen with chocolate consumption in Europe and the fears around it, colonization wasn’t merely affecting native societies in the Americas. Europeans were also becoming colonized, though to a lesser degree, by adopting native tastes and trends. In the 16th and 17th century, chocolate consumption in Europe would become more widespread and accepted, with chocolate being produced in homes and coffeehouses alike.

Works cited

Juarez-Dappe, Patricia. “Chocolate Encounters.” YouTube, August 26, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G8BW-HHWI88

National Geographic, “June 7, 1494 CE: Treaty of Tordesillas”, NationalGeographic.org, October 13, 2023. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/treaty-tordesillas/

0 notes

Text

Cacao in Mesoamerican Society

Chocolate is arguably the most popular confection in the western world. The Swiss alone consume an average of 19.8 pounds of chocolate per person annually. However, chocolate wasn’t always a mass produced confectionery. For centuries, chocolate was produced in small quantities for a select group of people. Cacao’s botany resulted in cacao and chocolate being used to reinforce social hierarchies and connect humans with the gods.

Cacao’s botany had unique social, political, economic, and societal implications for Mesoamerica. However, before discussing cacao’s effects on Mesoamerican societies, it is important to understand the origin of cacao cultivation and nature of cacao production. Cacao was first cultivated by the Barra people of Soconusco, Mexico, a civilization that predates the Olmec; the Olmec then perfected the processing of chocolate, and this process spread to other civilizations. Cacao is particularly difficult to cultivate. For starters, cacao only grows within 20° of the equator in a temperature range of 60℉ and 95℉; furthermore, cacao trees can only grow in shade, and must be planted under larger trees for protection against the Sun. After some time, cacao trees will start to produce flowers; only 3 of every 1,000 flowers on a cacao tree will become cacao pods. Once the cacao pods are mature, they must be delicately harvested by a large workforce, using machetes to carefully separate the pods from their roots. After being harvested, the cacao pods are cut open, revealing the cacao beans, the component used to make chocolate. Cacao beans must undergo a series of steps to be consumable, including fermentation, drying, roasting, and winnowing. First, cacao beans are left to ferment for several days to remove the pulp from the beans. Next, the beans are dried out in the Sun; the length of this drying period depends on the weather. After being dried, the beans are roasted. Next, the beans are winnowed; winnowing is the process in which the edible cacao nibs are separated from the inedible shells. Finally, the nibs are ground and blended; this resulting liquid, called chocolate liqueur, is molded into the desired shape, creating chocolate. The limited growing region and intensive processing of cacao meant that chocolate in Mesoamerica was a limited commodity.

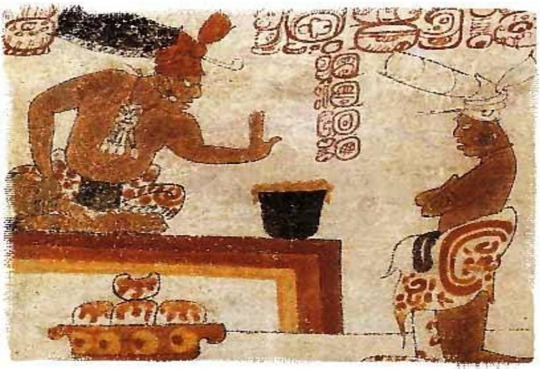

As stated earlier, cacao’s botany led to it being a limited good in Mesoamerican societies. This, in turn, resulted in cacao being used to reinforce societal hierarchies. As cacao was a limited good, only nobles could readily afford it. Chocolate was also difficult and time consuming to prepare; instead of producing the chocolate themselves, nobles had servants prepare their hot chocolate beverage. To further show off their wealth, nobles had their chocolate drinking vessels intricately decorated with images depicting cacao being served to nobles and the gods. The image below is an example of how chocolate was used to reinforce social hierarchies. In the painting, the man serving the chocolate is kneeling, while the man consuming the chocolate is sitting on a throne, showing a class difference between the two. Historians know this beverage is chocolate due to the foam on the top of the drink, as various accounts describe Mesoamerican chocolate as being a frothy drink.

Additionally, the Mexica, also known as the Aztecs, used cacao beans as a form of currency. According to the Codex Mendoza, 4 1⁄2 hours of work was equivalent to 1 cacao bean. When a Mexica noble drank a cup of chocolate, they were literally drinking money, reinforcing their status as the elite.

Not only was cacao used to reinforce social hierarchies, but it was also used to connect mankind to the gods. In the Maya myth of origin, cacao was one of the primary ingredients used by the gods to create mankind, along with yellow corn, white corn, and paxtate. This link between humans and the gods was strengthened further with cacao’s importance in the continuation of the life cycle. In the Madrid Codex, the gods are displayed as watering cacao trees with their blood; when humans consume cacao, they are nourished by the gods. In order to nourish the gods in return, humans would offer chocolate and other foods to the gods during festivals like the Five Dangerous Days; these ceremonies were key in continuing it. Cacao trees also featured in the pantheon of sacred trees, trees which were responsible for holding up the sky and connecting it to the earth, acting as a pillar between the two realms.

Cacao held great significance in Mesoamerican society. As a result of cacao’s limited growing region and labor-intensive cultivation process, cacao was a limited commodity. This led to cacao being used to reinforce social hierarchies and connect mankind with the gods.

Works Cited

Castillo, Lorena. “The Most Surprising Chocolate Statistics and

Trends in 2024.” Gitnux.org, December 16, 2023.

Juarez-Dappe, Patricia. “Cacao Origins.” YouTube, August 21, 2020.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y3NoKpG2PtU

Juarez-Dappe, Patricia. “Chocolate Encounters.” YouTube, August 26, 2020.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G8BW-HHWI88

1 note

·

View note