Afangar (icelandic): To look forward and back. A stop in the road. To take it all in. Artists in conversation with artists.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Artist, Colleen Toledano

Meet in the Middle. 2012, Porcelain, balsa wood, rice paper, plexiglas mirror, 60"x24"x12"

Smoke Screen, 2012, Porcelain, balsa wood, rice paper, red LED light, 36"x14"X20"

Life Body Study #1, 2012, Porcelain, wood, plexiglas mirror, vellum, resin

36"x50"x15"

SLICE LIFE #2, 2012, PORCELAIN, WOOD, DECALS, HARDWARE

WALL FAT, 2010, Porcelain, plaster, paint, flocking, hardware, flocking

ENABLER AND DETAIL, 2008, PORCELAIN, PLASTIC, PAINT, HARDWARE

SMOTHER BLUSH, 2005, PORCELAIN, PEWTER, RUBBER, LEATHER, SYNTHETIC HAIR, GLITTER, 32"X4.25"X4.25"

NIPCURLER, 2005, PORCELAIN, PEWTER, SWARVOSKI CRYSTALS, 25.5"X4.25"X10"

Colleen Toledano is a mixed media artist with incredible ceramic skills. Her work deals with body, architecture and beauty vs prettiness. Colleen is also working on a project in Buffalo, NY that honors artists and craftsman making handmade objects. The project emphasizes the importance of community building by bringing together local farmers, artists, and other Buffalo natives to share ideas, get to know each other and learn about one and other's creative outlets. Learn more Here: https://www.facebook.com/BHBPROJECT/info https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1932051299/bhb-project-build-handmade-buffalo The interview below is a discussion between the artist and I about her meticulous and awe-inspiring work:

A: Your work calls to mind artists like Paul Thek, Alina Szapocznikow and some influence of Rococo flourish. Can you talk about your influences and art historical lineage?

C: I have always been influenced by opulence, excessiveness, and abundance. These are concepts that I think are both of personal importance when I make connections between one’s body and home. So making reference to the Rococo period and style only seemed natural. Maybe because I am a ceramic artist I seem to be more aware and influenced by other clay people, such as Nicole Cherubini’s work that I think also references abundance in our culture of mass consumption. Also Sara Lindley’s ceramic, skeletal furniture sculptures. I admire her work technically because I know how finicky porcelain can be, but also the consideration to this and how using the clay gives her pieces an undeniable vulnerability and fragileness that I seek to have in my pieces. But I attempt to simultaneously make them appear strong and in control. I have been influenced by artist, Damian Ortega’s sculptures that have made me think about my relationship of my own body with the material world around.

A: I love the way that you weave surface/exteriors into the visceral body of an object. The piece, Slice Life #2, for instance has this beautiful, subtle detail of a white and blue floral pattern that one might find on wallpaper or fine china, it runs in between a pink, marbleized shapes that are reminiscent of skin and tiles all at once; this all lives in a compact “slice” of a brick wall. I’m so drawn to this piece because it is so full of contradiction and unity all at once. The “decorative” flowery detail is also a network of veins breathing energy and life into the piece. I feel like this piece is talking about the inside and the outside existing as one and being on an equal plane - as if to say the icing is not a mere topping but it is integral to the cake. What is it that attracts you to surface details as well as the insides?

C: I consider the duality between the exterior and interior of my pieces to be co-dependent of each other. Without the other, one would not exist. I can never ignore the “insides” of the pieces because for me it’s what drives the power of what I am talking about. I enjoy assigning “decorative” elements to the context that can feel or can be considered as messy or grotesque. This contradiction gives importance to the necessary role that it plays in the overall concept. Creating beauty helps to draw the viewer into the piece and demanding consideration and introspective to the dialogue of the various concepts involved.

A: I notice that framing is a consistent element in your work. Pieces such as Smoke Screen, Wall Fat, Slice of Life, Lux Luggage III and more all have a defined perimeter. Calling attention to the fact that these pieces are on display creates a sense of distance while making them feel all the more tantalizing. What role does framing have for you?

C: This is my attempt to bring attention or give important presence to the piece. By “framing” or giving a “defined perimeter” I am asking the viewer to mentally and visually enter my pieces. This is allowing for investigation within a small and concentrated context.

I am also interested in the rigid structure of architecture, comparing it to the skeleton of our bodies. Without this integral component neither would be able to hold themselves up. Making the framework vital to the integrity and strength of both.

A: I notice your drawings have a “barely there” quality, delicate, yet precise like blueprints; while your sculptures have a real sense of weight. What are the differences and/or similarities in the two processes? How does one influence the other?

C: I spend a lot of time in my studio thinking and considering the various materials that I use and how they work together or against each other. I try to create a dialogue between the different materials that contribute to the overall concept of the piece. I enjoy pairing soft and delicate materials next to hard and sturdy materials because I believe they emphasize each other characteristics even more. I am concerned that my viewer can experience the feel of the materials with out touch them. That the weight of the material is apparent when considerably used. Lightweight, often translucent materials are used when I want to speak about a delicate, fragile, and/or sensitive situation. Heavy weighted materials are almost always about strength and power. Although there are times that I have tried to make contradictions, such as in the piece Meet in the Middle, the white paper fence is the component that demands attention and in the narrative is the most desired. But by using the delicate material it is also perceived as the most difficult to attain.

A: Some pieces with multiple components such as, Meet in the Middle, seem to be more narrative than a piece like, Life Body Study. Is narrative an important element in your work and does it manifest itself differently at different times?

C: Presently my work has become more narrative as I attempt to visually communicate the complicated relationships and events in my life. In the past I have discussed several ideas of how “control” plays a role in my life, but I was always concerned with talking about it universally in order to make it more accessible to my audience. As the work becomes more narrative I am interested in my viewer experiencing the way I handle control by conceiving of pieces that when in their presence an emotional and/or physically reaction occurs. I want to the viewer to feel how I felt.

A: I admire the way you defend “girliness” in your series Foxy Fuss, by embracing femininity while demonstrating an awareness of the sometimes wincingly grotesque means of attaining beauty. Can you talk about what beauty means to you and if it relates at all to question 1, in regards to surfaces.

C: In thinking about this question I remember using the word “pretty” often when I was making the Foxy Fuss series as opposed to the word “beauty”. The two words had different meanings and connotations to me and still do.

In my mind I assigned youth and delicacy, and maybe a little weak, to the term “pretty”. The series Foxy Fuss had much to do with how I could use my femininity as my power, giving me control in any situation. Acknowledging that “pretty” was not always seen as powerful or strong, I tried to play against these ideas by making objects that were usually seen as aggressive and masculine. I made these objects, such as weapons, ultra-feminine and desired by using qualities that were commonly associated with “pretty” like, curvaceous forms, soft pinks, and floral aesthetics.

This use of attaining “beauty” was more relevant in the two series that preceded Foxy Fuss; Bodily Trays and Sufficient Stitchery. Conceptually I was speaking about extreme actions that are done to attain beauty. I was thinking of “beauty” more in terms of aesthetics, what looks pleasing to the eye. Also how there is power associated in being able to make those decisions to attain this beauty and that one should feel good about it, never apologize for it. This is a very third wave feminist viewpoint. There was still use of soft pastel colors, but there were a variety of soft and hard materials within the same piece. I saw the use of a variety of materials gave more balance between masculine and feminine within the same piece.

0 notes

Text

Musician, Micheal Rider

Micheal Rider is a student in a class I worked as a teacher-assistant. He is a very artist and musician. He just released a new album, Hidden Treasure, which you can listen to here: https://myspace.com/michaelridermusic . Below, we discuss his creative process and influences:

A: you seem to be interested in power dynamics and the role of hero vs. victim. songs like “American Fighter” and “Sister’s Keeper” talk about staying strong even when you don’t think you can and dealing with pressures. What sparked you interest in these ideas?

M: Hero vs. victim has always been a big motif in my writing. I think it was a little more visible with my last album, Lighthouse, but it still remains a strong theme in these new songs as well. In my last album, I was very much a victim and I surely made it come across to the listener. Songs like “Hero”, “Moratorium”, and “Angel” I write in a persona of crying out for help, as a victim in search of safety or something. During that time I was going through a lot of personal changes, and a lot of struggles just being a teenager. I was also just very young. In those songs, the lyrics are very much in a point of weakness and sadness, bounded by longing. Songs like “Lovely Lady” and “Guillotine” I write in a persona of pain, lashing out as the victim. When being a victim for so long, you lash out in anger and rage, and those songs definitely do that for me. “American Fighter” and “Sister’s Keeper” are similar, but I think they are more mellow than those on Lighthouse. Lighthouse was so much about being victimized lyrically then dressing them up with drums, beats, and tons of voices to scare off whoever I was writing about. I dressed up those songs like I was putting on armor, trying to make myself seem powerful, a warrior ready to fight, or to protect me. In the new songs, I was so much about trying to appear wise. As a writer, I tried to put my perspective in the eyes of an old man – so the victim in the new songs is very much jaded, olden, and supremely wise. The first half of the album, Hidden Treasure, he is very much wise and jaded, but he is definitely mellow, but in the second half, he won’t be so mellow.

A: I love the vulnerability in your work. Your music is almost operatic and theatrical in the way that you belt out lyrics and have a sort of pleading, aching feeling in the piano. Is it difficult to be so open with others? How do you get to a state of mind where you can write and play music so freely?

M: I have to be honest as a writer. Writing lyrics is such therapy for me. Its funny probably because people who listen to my songs most likely think I’m a nut case, but I’m a pretty level-headed person. I think I take out my craziness in my music. My lyrics are definitely vulnerable, but like I said I dress them up with lots of drums, voices, and guitars to make it seem more powerful and confident. I think the people who enjoy my music really like that about my music, the honesty in the lyrics. My music isn’t for parties and raves, but more for laying in your bed alone in the dark. Everyone needs a few songs for that.

A: I can hear influence of the Dresden Dolls, Adelle with the roots in a gothic drama and pop melodies. What musicians influence you?

M: I love Dresden Dolls. I grew up listening to Amanda Palmer. She is such a strong composer and singer. Nobody dislikes Adele, I am very much a listener for her voice and lyrics, and she is such a pro and a legend, I love her. Everything musically really inspires me. It’s really important for me to keep an open ear for anything and everything because everything is inspiring if you just really listen. On this record specifically I was listening to a lot of The Reign of Kindo, Sucre, Ingrid Michaelson, Chelsea Wolfe, Kate Bush, Jesca Hoop, James Blake, Bright Eyes, and KT Tunstall. Those are just the names I remember. ;)

A: How do you get such a full sound in your music? How long have you been playing and what started your interest in

M: Full sound comes from the piano I think. The piano is such a milky instrument, alluding to such a wholesome energy. The piano is such a feminine, breathing instrument, it can scream in sadness and scream in anger – its perfect for my work I think. It’s a very dramatic instrument as well and really has a life of its own. But I think my other formula is my voice. In the recordings, I am a big fan of layering my voice in vocal harmonies and choosing dissonant chords on the piano and making the voice and piano wobble between major and minor chords to create a sense of moody volume and roundness.

A: What are your non-art related inspirations?

M: TV Shows! For sure. I am such a big fan of Netflix. Even though it is an art form, I’m going to say it anyway! Shows like Game of Thrones, Breaking Bad, House of Cards, Walking Dead, Pretty Little Liars, Downton Abbey, watching these shows and movies, at that, really inspire me. The drama is inspiring. Currently I am writing to a lot of TV shows as inspiration, so the music is coming out being more cinematic than theatrical, but both I love and both deeply fuel my work.

A: does your visual art inform or inspire your music, or vice-versa?

M: They go hand and hand. I don’t know what it is I am trying to say, as a creator or human being, but whatever it is, I’m trying to say it in both my music and art. Like I said, I don’t know what it is. It may be a mood, essence, or feeling, I have no idea. Once I’ve finally said what I needed to say, I guess I am ready to die.

0 notes

Text

Interview with Oona Stern

Oona Stern is a New York based artist dealing with concepts of nature, space and an awareness of one's surroundings.

deDomination (baroque); digital print on adhesive vinyl; 20 'one-sheets', 29 7/8" x 45 7/8" ea; 2008-9.

brick; neon; 29.5" x 33.5". 2009.

the sound of grass growing; carpet, sound; 14' x 76'; 2005. Sound designed in collaboration with Sara Stern. Long-term installation, commissioned by Art in General for Bloomberg, LP, NYC.

stone curtain wall (BZ); cast gypsum, steel cable, hardware; 8'6" X 8'6" X 2"; 1999. Galerie Reinhard Hauff, Stuttgart, Germany.

meander, grass and gravel; 12' x 50'; Huntington NY (Long Island), 2012

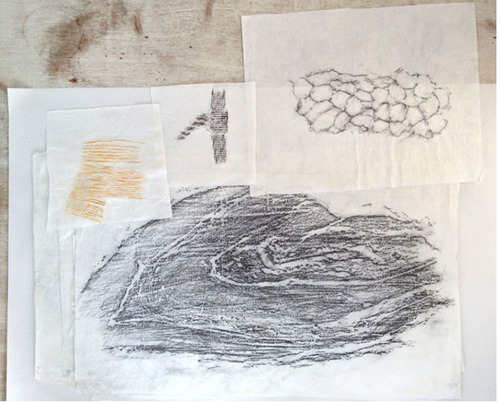

Arctic Drawings:

untitled (rock); mixed media on paper; 19" x 13"; 2012

rubbings; crayon on paper; 2011

Antarctic Drawings:

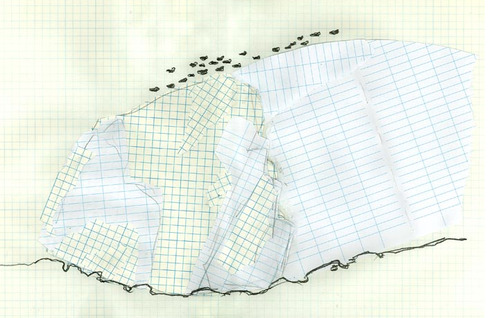

op glacier with gull; mixed media on paper; 10.75" x 16.25"; 2009

glacier plaid; mixed media on paper; 11" x 14"; 2009

skua egg; mixed media on paper; 4.675" x 7"; 2009

A: Your work has always had a strong sense of solitude and and contemplative humor; however, I feel like your recent drawings encompass those feelings even more so than before. Can you talk about some of the experiences that are inspiring you lately?

O: Many of my recent drawings come out of the trip I made to Svalbard in the Arctic Circle. This was part of a collaborative project with the composer and sound artist Cheryl Leonard. We sailed on a schooler for two weeks as part of the Arctic Circle residency, and we also explored the region on our own, winding up with an audio-video installation at the Insomnia Future Music and Techno Festival in Tromso, Norway.

A: Do you consider time, weather and space to be part of your mediums?

O: Well, I think time is different in the Arctic. I don’t know if it’s a medium but it must be a part of the narrative. I haven't figured out how to bring that more to the foreground in my work yet, but I think at some point I’ll address it more. My audio-video collaborations with Cheryl are making me pay attention to time, but I feel like I am just beginning to understand how time can play a role in my work. I’m also paying more attention to the relativity of time. Glacial time, for instance, is vastly different than human time. When things take eons to occur, it's not something we palpably comprehend. I want to make some translation of this phenomena into the vocabulary and medium of the art project..

I think of weather as time and materials together. As for space, I think in terms of structure. Space is definitely part of my tool box – whether as a function of the materials I choose, or as part of the site, or in the experience of the viewer. And now that I think of it, time is a function of space as well: how a physical space is experienced or revealed is a function of time.

A: I see your installations as drawings in space. Can you talk about how drawing on a rectangular flat surface like paper is different from drawing in a three dimensional space?

O: It’s the same. It’s just using a different material. Maybe it’s a bit more like a relief but the thinking is the same.

A: Do you find the restrictions in working on paper limiting?

O: I don’t think so, because I still think of it spatially. It’s not a limit, it’s a door or an ocean. There are two ways of thinking about it; just like you can imagine the coast as either a dead end or as an expansive gateway. When I’m drawing I think of it as a sample. Like an exploration of a little piece that talks about a bigger story. I draw and draw to think about things over and over again. Its a process, not a final state. And really rarely does a drawing become a finished piece.

A: I like the way you phrased that - very much on the opposite of abstract expressionists who proclaimed the flatness of the page. I like thinking of it as a deep, living space.

O: It’s also sculptural. It’s rare that I render something realistically but none the less, the imagery relates to space and form which is three dimensional. It’s still representation but in an abstracted space.

A: Can you talk about what it was like working alongside scientists? What were some of the differences and similarities between artists and scientists?

O: Well, here's an example: A couple of years ago I received a residency from the National Science Foundation to go to Antarctica. It costs them a lot of money to send people down there. While they could be putting that money towards hard edged scientific pursuits, they believe that bringing artists in, and allowing them to observe and think about whats going on in the natural world, and to observe what scientists do is worth the investment. Two things happen. One is that artists make their own observations, and create work as a kind of parallel to scientific research and findings. The other is that the projects created by artists have an audience which goes beyond the scientific community. And so it becomes a kind of outreach program. Maybe it’s not hard science but it’s a bridge between scientists and other people. Or maybe it is another valid way of processing the world. It’s more like poetry or meditation. Maybe it directs scientists to answers they wouldn’t have otherwise been able to come to. The NSF has supported artists' projects for years, and no matter how dire their financial situation is, they never just axe the program. They firmly believe that science should be intertwined with culture.

But to answer your question more directly, Artists' practice is similar to scientists' in many ways. We artists observe the world around us. I really see that as a kind of data collection. And then this information is translated into different mediums of communication. For scientists its papers, talks, hypotheses, predictions. For artists, its poetry, narrative, objects, imagery, theater....

A: What do you think the role of an artist is in culture? Or your role, anyway?

O: I have no idea. Honestly. Do you know the story of Frederick the mouse? It's a childrens' book by Leo Leoni, illustrated by Eric Carle. It’s fall and all the mice are collecting food for the winter and this mouse, Frederick, just sits in the sun and the others are calling him lazy and telling him he’s going to die if he doesn’t collect food. He replies that he is collecting sunny thoughts. When the winter comes they all share their food with him and say “ well, what are you going to share with us?” and he tells them stories about the sun and the colors and he enriches their lives during the bleak season. This may be an overly simplified parable, but I think we need art.

A: Life would be too boring if all we did was survive. I think the best things artists can do is go forth without knowing if there is even a step in front of them. It’s a demonstration in faith.

O: I completely agree that faith plays a major role in it.

A: On a slightly different note, I have a quote that I wanted to share with you. It’s from a book I read recently by Georges Perec called Species of Spaces and other Places: “What we need to question is bricks, concrete, glass, our table manners, our utensils, our tools, the way we spend our time, our rhythms. To question that which seems to have ceased forever to astonish us. We live, true, we breathe, true; we walk, we go downstairs, we sit at a table in order to eat, we lie down on a bed on order to sleep. How? Where? When? Why?”

I think part of your work is questioning the things we take for granted. You invert the grass between slabs of concrete but (by?) putting concrete between planes of grass. Or you zoom in on patterns on rocks, eggs, driftwood. Is there a process of training your eyes to seeing, really seeing and experiencing the oddness in the way we live but fail to take notice of?

O: Maybe not the oddness; rather, the ordinariness. It’s easy to see something special and unusual in something weird. You know, there are reasons why there is brick and then mortar and than another layer of brick on top of that .Most people pay no attention to that. The mortar is what gives a wall structure. If you just had loose bricks you wouldn’t have a structurally sound wall. There are conventions learned over time that we’ve stopped thinking about because our generation is privileged enough to have these problems solved for us. I like looking at ordinary stuff because it’s overlooked, but there is plenty to think about. Its just my habit to see the world that way. I think we should feel a little humility in the face of all the beauty which lies within the mundane.

A: I want to talk to you a little bit about making public art. It’s a tricky arena. There are plenty of public artists who dumb the work down to grant the viewer an easy reading. There are other artists who decide that they don’t care at all what the public thinks - i’ve read some interviews of public artists who are downright disrespectful of their audience and dub the public 'idiots' - all the while using the community’s tax dollars to fund their work. When I worked with you I noticed that you are very down to earth. You don’t dumb your work down but you welcome the many different readings from viewers with different backgrounds.

O: Well, they are the ones who will experience the piece, and what’s important is for that experience to be meaningful. Even if they don’t get exactly what I’m trying to say, hopefully I can think about what’s interesting to someone else, and create work where there is something for everybody. When we worked on that installation in Ellwood Park in Huntington, one of my favorite moments was when we saw a kid was playing at something like hopscotch. We had just returned from lunch, and the kids had discovered the piece, and were hopping and skipping all over it. It was so incidental, and not what I was thinking of when I was making the project, but nevertheless wonderful to see somebody experience the work with such joy. Now, in fact, I design similar garden installations with that “use” in mind. I've learned from the genuine experience of the passersby, and absorbed it into how I design the work.

A: I think one of the pleasures of art is opening it up to the public and not just talking to other artists - it can become very incestuous.

Does it change the way that you see your work when it’s made in a gallery or in a non traditional art space like a park?

O: I’m not sure if there is really a difference. The gallery is a public space after all. I’ve done pieces for people inside their own homes as well - even though it’s a private home it’s still a space that’s experienced and has to relate to the architecture and the people inside. The logistical details are different but the process is the same.

A: Have you been drawing all your life?

O: I think so. It’s telling that when my studio shrank down all that’s left at the moment is my drawing table - that’s the most important part.

A: And you're versatile. There are immediate process here like directly putting material on a surface, and there are more process oriented methods where you’re scanning an image, reworking it, doing a rubbing - scanning that, using one color as opposed to two, using texture or just line.

O: I’m familiarizing myself with the vocabulary. When I draw and redraw patterns or structures, and when I work over a print from a rubbing I am thinking about the imagery in two ways. From the source: What does this edge on the rock mean? What does it say about material, structure, history, geology, physics...? And from my mark-making: How do I want to draw it? Hard lines, gestural, representative, what color, what value...? I’ve figured out how to draw ice after maybe probably a hundred drawings. When I draw over a print of a rubbing I'm forced to confront the same marks over and over, and I have to think about what they really look like, what effect on the image, what impression on a viewer. The rock’s edge is always there and I have to deal with it every time I rework the print. I know the marks each of my materials make, and it’s a matter of choosing which to use.

A: It’s almost like having a prompt.

O: Yeah, and I have to respond to that prompt every time. I can choose to ignore it but that’s still a conscious decision.

A: It seems to me that there is a difference between your object oriented work as opposed to the drawings. The drawings are more explorative; whereas, the objects/installations you make seem to have already been determined before you made them.

O: The drawings exemplify a state of learning and the objects are decision making based on what I've learned from drawing. I do something over and over again in drawings to become familiar with, and understand the subject; if and when I decide to translate that to something other than a drawing I’m no longer learning, I’m acting purposefully and putting it out in a more determined fashion. Sometimes what happens is that after a series of drawings, and idea for a sculpture will present itself to me. A kind of “Aha!” moment that arises out of a somewhat meditative process. The forms and materials will often seem obvious. Maybe that's what you were touching on when you described the objects and installations as decisive or determined.

A: Do you identify with performance art? When people interact with your work does it become a performative object or a catalyst for performance?

O: I guess it does, but I’m not involved in that aspect of the piece. Maybe that interaction becomes performance, but who is the audience if the viewers are the performers? I made a piece in the New York City subway. I rented advertising space to put up my own posters. The idea was to 'erase' the advertising which is usually present, and to return the space to more neutral architectural functions. The ads in the subways are installed in public spaces, and you have to experience it whether you want to or not. Its actually a kind of theft of public space for use in private commerce...Anyway, I created an installation which was basically wallpaper. I chose to draw wallpaper because that’s a form of imagery and material which is associated with walls - It’s not what I think is pretty or some 'decorative' imagery - that would just be me advertising. I didn’t want to announce it as artwork by putting my name on it or anything. The work would be there for the passerby to notice - or not. Perhaps taking note of the quiet image that normally serves as ad space - or not. This piece requires and audience – it had no meaning otherwise. Does that make it performance, albeit one which may well be unconscious to the participant?

A: I’m fascinated by that idea. As an object maker myself I sometimes imagine myself drowning in my home from all the junk i’ve made and situated around me; so I like the act of making art by subtracting as opposed to adding.

On a different note, I notice now you’ve been making things that are fairly untouched by man; however in your earlier work you were making things that dealt more with the representation of nature as opposed to the reality of it. Can you talk about this a little bit?

O: I’m interested in how we apply faux wood finishes to plastic and other man-made materials - it seems so pointless. Design has changed recently, but before people were comfortable with plastics and steel we wanted those materials to look like something else, something natural and more familiar. Really, why make siding which looks like wood clapboards, or brick and mortar? Why not decorative patterns like the Greeks developed – abstracted foliage or even geometrical patterns...? The faux finishes are funny and theatrical too - like a stage set. There's some cultural coding which goes on that just fascinates me.

The residencies I’ve done in the Antarctic and Arctic have influenced me to shift my work away from man-made structures and cultural artifacts, towards nature in its more pure state of being. Many of the drawings that I’ve been doing lately are related to pattern and geometry. But instead of architectural patterns, they are drawn from nature. I was looking at the structure of ice in an almost architectural way - how its held together. We sometimes think of nature as a wild place but it is actually highly ordered. The waves in the sand or stripes on zebras are formed by organizing, scientific forces. Nature isn’t just pretty, it’s structured in the same way that a building is.

As these ice drawings developed, I had an idea of rendering glaciers as a kind of “ plaid.” It’s not really plaid, but the familiar pattern helps me see how the forms and planes and spaces of the material all come together. You asked before how I see artists' practice as similar, or dissimilar to that of scientists. Early explorers learned a lot by simply drawing ,and that’s what I’m doing too.

A: Is this the first time travel has been a part of your work?

O: Travel isn’t so much content as it is an opportunity. Because Antarctica is so far away and so special it becomes a different kind of experience. There are so few people and the space is so huge and meditative. The remoteness allows access to things I don’t get to experience in my daily life. Many people think of that climate as being harsh and unfriendly; for me it was incredibly relaxing to just sit in this monstrous, white, icy place and just be there.

*For those interested (and I can't imagine who wouldn't be) here are some links to learn more about Oona Stern and Cheryl Leonard's ongoing projects:

http://vimeo.com/user5988935

http://atlengthmag.com/art/ice-notes/

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bacchus!!

A couple of my talented friends put together an artist collective called Illegal Gallery, in which they exhibit art in unconventional ways such as meeting at certain subway stops and putting on mini exhibitions. On August 19th they are putting on a one night show in Dumbo, Brooklyn!! The theme of the show (as you may have guessed) is Bacchus - so it should be a fun and interesting night whether you're passionate about art or are more the type who attends openings for the free wine There will be sculpture, painting, installation, performances, music, and good times to be had!! Tickets are only $10 and you can boy them online or at the door. Visit the link here! Please come! Me and many great artists will be involved in this great exhibition!! http://igbacchus.tumblr.com

0 notes

Text

Interview With Katherine Bradford

Katherine Bradford is a painter and object maker living in New York. Her work demonstrates a human touch in both the handling of paint and the way that she shows a more humble and tender side of monumental symbols.

Liner Soft Iceberg Paint on wood, plaster and cloth, 20" x 12" 13", 2010

Man Under Water

Oil on canvas, 8" x 6", 2010

Night Divers

Parting of the Seas

Gouache on paper, 10" x 14", 2006

Ship Blue Harbour

Super Flight

Oil on canvas, 12" x 9", 2011

Super Flyer

Oil and collage on canvas, 48" x 36", 2011

Swim to the City

Oil on canvas, 20" x 16", 2009

Titanic Orange

Titanic on Piano

Plaster, cardboard and paint, 8" x 13" x 14", 2011

A: I think about narratives when I look at your work....not so much written stories but oral stories. Because of the way you repeat symbols. Symbols and phrases are used repeatedly in the telling of myths and stories that predate books so that they would be remembered and passed down. But even still the story changes a bit each time. Do you use repetition as a means of remembering and story telling?

K: Well, you’re right, I love repetition. I do use symbols. I started out as an abstract painter - what you might call a mark-maker, then, some of the marks I was making started to look like namable things. I took them out because I thought of myself as an abstractionist - which is kind of silly. As time went on I let the shapes come in. Faces, legs, smoke stacks. And I thought “Oh no now what do I do!”

A: Was there a certain sense of guilt in moving away from abstraction?

K: Not a sense of guilt but a sense of being in foreign territory because I didn’t want to have to contend with the history of figuration. We all start out drawing the figure and life drawing, and I wanted to get away from that. So I had to invent a way for me to get a person into my work. My big attraction to Superman is that you can describe him by painting a blue shirt, red underpants, red cape and boots and it just starts looking like Superman.

A: And we know those blocks of color so well for being Superman’s outfit that you can really play around with it and still have the association.

K: Yes. I imagine that true comic fans and people who revere Superman might not appreciate what I’m doing because I’m being a little bit subversive--taking what we know about Superman and turning it on its head .

A: Well, he doesn’t seem heroic for one thing. In some of the pieces where he is flying, it doesn’t necessarily look like he is rushing over to save someone; he’s just flying for the pure joy of flying.

K: Yes. You talk about narrative and story. Well, I wanted to stop short of telling a “Superman story” so I’ve gotten it down to just Superman flying through the air because that’s such a great thing to do on a painting. That is what I’ve had the most fun with: isolating him in space.

A: On that note, one of the things I wanted talk about was the idea of freedom. The two main ideas about freedom, one being that you are free when you can do what you want, the other being that you’re free when you have no desire for more than what you have. I’m wondering how you see Superman or painting in general. Is Superman free when he doesn’t want to save anybody - when he can just enjoy the fact that he can fly?

K: That’s a pretty radical thought, I never thought of Superman just tooling around in the sky not saving people. It’s not part of the legend. But it’s a great idea, why not?

I think anyone who makes a painting in a way is talking about the possibilities of paint. So, you’re right, I think all these things I paint about: the boats, buoyancy, flight are all traced back to making a painting and all of the possibilities that entails. What appeals to me is thinking I can do anything I want. Where else can you feel that?

A: Oh yeah! Even in sculpture it’s a different kind of freedom than painting because you have to worry about gravity and the limitations of the material. Whereas, in painting - it doesn’t have to obey the laws of physics - it works a certain way because you painted it to. So maybe there is a bit more freedom in painting in that sense.

K: Well, that would be an interesting debate wouldn’t it? Which has more freedom and limitations.

A: You make objects as well, right?

K: I do. And I call them “Objects” too.

A: Why is that?

K: Sculpture sounds so serious and I’m kind of playing around.

I made the little pieces because I wanted to do some videos and they were my props. But I had them lying around the studio and people said they liked them.

A: Have you been noticing the lines between painting, sculpture and other disciplines blurring over a long period of time or are you really feeling it the most now?

K: I have been feeling and seeing it a lot recently. I’ve been writing on some of my paintings “ The Golden Age of Exploration” because I feel we are in a time of exploration and experimentation - and that is a great value in of itself. And I think it’s a term coined by sea farers who were going out and looking for new lands. That was the Golden Age of Exploration, and now maybe we are sensing that in Brooklyn.

A: Exploration is the greatest thing about the art process. It’s hard for me to start working without any kind of idea in mind; but it’s definitely the best when the idea is a starting point and you completely stray from it during the process. I love surprising myself.

K: I love how that is very much in the air now. Intuitive art making as opposed to conceptual art making where you have an idea and then you make something to illustrate the idea.

Now I know what you’re going to say to me: Do you know what you’re going to paint before you start?

A: haha, I was going to ask that

K: it is an interesting question because I can say no, I don’t because I start painting by just putting paint on the surface. However, after you’ve been painting for a while you have a vocabulary of reoccurring shapes and themes. Even though I’m making it up as I go along I’m using the same symbols over and over again. That’s a very reassuring feeling; I can remember as a young painter that horrifying feeling of “ what to do?”

A: You don’t feel that anymore because of the symbols you use?

K: Much less because I have so many leftovers. It’s like being in a kitchen and you just have so many leftovers that you can throw together a whole soup.

A: I think it further illustrates the idea that it doesn’t always matter what the image is but how you make it because people are all so similar that the particulars of the story don’t always matter because at the core it’s all very much the same.

K: you think we’re all so similar?

A: I guess I’d like to think so...

K: well, a lot of art has been made that addresses the differences between races and genders. I don’t work with that at all.

A: You don’t?

K:...Well, maybe I do. ..the male/female thing. It wasn’t important to me to make Superman look male, and some people thought he looked female. And one reason I like making Superman is that because of his costume I don’t have to worry about his skin tone so much.

I do a lot of paintings of swimmers and I always think “Oh no, all these swimmers are the same skin color” And then I have to decide if I want to make them all different colors, and which colors, and it becomes a statement about race.

A: Well, you paint them all in a kind of pink color - and that’s not necessarily a real skin tone at all, it makes them funnier.

K: That was such a breakthrough to me -to realize I can use humor in my work.

A: It’s a relief to strive to make yourself laugh when you’re working. You can get a message across more clearly sometimes and with more delight for you and the viewer if you use humor - but it can still be incredibly serious underneath.

K: That’s a great word: delight!

A: That word really comes to mind in your work - I think it’s because of this incredible sense of light in your paintings. It’s so hopeful.

K: I’m so glad. I had a show at Edward Thorp Gallery in Chelsea and the review in the NY Times mentioned a sense of “joie de vivre” in my work. I hadn’t paid much attention to that or done it on purpose but now I’m thinking about it because I value it.

A: Are the paintings a struggle to make?

K: ha ha ha yeah...sometimes it can be pretty awful! Years ago, my younger sister told me that my paintings were really horrible - dark and serious. And she said to me, “Kathy, I really think you should sit and watch I love Lucy reruns before you start your day in the studio.” I never did do that, but I got her point - which is to get into a zone where life is ridiculous and absurd and funny!

A: One of the things I think is really funny about the work is in the pianos - I can’t stop thinking about in cartoons when there is a piano flying through the air and landing on someone’s head - the way it’s dramatic but O.K because they spring back up like an accordion. Is that kind of drama and comedy in your head when your working?

K: Hmm, my pianos aren’t flying through the air…

A: I was thinking of the object you made with a piano jutting out of the wall.

K: oh, yes! This one right here, it’s got a little ocean liner on it about to crash into an iceberg.

A: And that’s like taking the Titanic and making it comedic!

K: I know, my dealer did not like that. He didn’t want me to show these - he said “But Kathy, people died!!” He wanted me to stay away from it. I don’t know what I would say if someone asked me why I made it funny...

A: Well, what were you thinking when you did it?

K: Visually! I was thinking visually! The black piano, the black ocean liner, the white iceberg, the tension between the two, the beauty of the open sea at night.

A: And it’s so beautiful to imagine the black sea and black night sky looking like one endless shape.

K: Yes!

A: There is also a strong contrast between almost immanent peril and entertainment...

K: I see what you mean, like someone is about to get a pie in their face and that’s funny…

Oh God am I talking about that with the ocean liner? The Titanic disaster happened 100 years ago; but, in a way, it’s very close to 9/11 in the sense that something fell apart that was never supposed to fall apart.

A: But the obvious difference is that the Titanic is man vs. nature, as opposed to man vs. man.

K: or man vs. culture.

A: The boats you paint occupy space in a very different way than the swimmers, for instance. The boats are huge and frontal; whereas, the swimmers feel small and fragile. There is one piece on your website with a single swimmer with this orange skin against a beautiful blue sea. He looks so limp and delicate. He looks so weak as opposed to the structures we create to try to triumph over nature. I think it shows that without the things we’ve created to put between ourselves and nature, we are much more --

K: Vulnerable. I think vulnerability is a powerful emotion to bring out in art. I think the boats,the swimmers and Superman are all vulnerable in the way I’ve painted them.

A: They’ve all just had a dose of kryptonite.

K: Exactly. And the people who make art are vulnerable too. I like to see that. I like to stand in front of a work of art and feel that whoever made it had to make a series of decisions and wasn’t sure of what they were doing but persevered anyway.

A: I agree completely, I would much rather see an earnest artist fail than a more sly artist succeed without struggling. I prefer failure to feeling like someone is trying to outsmart me.

So you paint the sea and sky a lot in your work. I think those are such beautiful things to paint because they imply a kind of infinity. Plus there is so much mystery. I heard that supposedly we know more about outer space than we do about the deep sea. Is it the sense of mystery that attracts you?

K: Well, if you paint the sea or the sky it’s very forgiving. When I put the paint on it starts to quickly look like water or the sky. If you’ve ever tried to paint a cloud - you can almost do anything and it will look like a cloud - which goes back to the notion of freedom. I like being in an area that gives me a lot of room to experiment and invent. And that’swhy i don’t think I could be a portrait or figurative painter. It’s much more narrow in scope; although I’m sure someone like Alice Neel would disagree with me. But as far as I’m concerned I like to have my options wide open when I’m painting. That means having a wide open field where a mark can be anything.

A: So can you talk about your relationship to images? Some of the pieces I get the feeling that you paint directly from life.

K: You think I paint from observation? Hardly. I was never very good at painting from observation; I couldn’t stand life drawing. I would always start doodling instead. One thing I definitely paint from is other paintings. I tear images from books or print them out from the internet and I look at them while I’m painting.

A: What turned you on to making art?

K: I was living in Maine. It was the 70’s and I got to know other artists. I saw what they were doing which was amazing because I don’t think I really knew before that. I saw this intense relationship that artists have with their work and how all encompassing it is. I realized then that that was what I wanted.

A: I get a strong feeling of finding a sense of identity through a place, Is there any aspect of your work that is based on national identity or maybe just identifying with New York?

K: Well, certainly not an ethnic identity. Although there has been so much great work about that. But, I started to paint in Maine which is a very soulful, maritime place where there is a great deal of wonderful art that was made by people like Winslow Homer or more recently Alex Katz that has to do with water and boats and swimmers. I’m sure I was influenced by that. When I return to Maine in the summer I feel like it’s part of my identity, my home. It’s a very beloved place. There are about a million paintings of Maine because of this quality.

But you know I identify with Brooklyn and New York too.

A: Me too. I feel instantly at home in New York because mostly everyone came here from somewhere else, so you don’t feel like an outsider or a newcomer for long.

K: It’s very diverse which I like.

People often bring up children’s art, folk art and outsider art when talking about my work and I have to own that.

A: Do you identify with that?

K: I love folk art,that sits well with me. Outsider art is a misunderstood term - I’m not quite sure what it means. Children’s art is terrific but then you get into that murky area with contemporary art and the “my kid could do that” syndrome - which is tricky. But what is most important to me is a direct and simple expression going from me to the painting.

A: Well, that’s why outsider art actually didn’t come to mind because your work is incredibly rich with art history. So somebody who also knows art history can pick that out and enjoy the work from that angle, or someone who knows nothing about art can enjoy it simply because of the marks and image.

K: I identify with blunt. And awkward. Now there is another word I like. I remember a critic called my work awkward and my kids were rushing to my defense and I had to explain to them it’s not such a bad thing in visual art.

A: Well, its such a tense, embarrassing and wonderful place to draw work from. It’s easy to relate to but it is difficult to paint.

K: The situation of awkward is very rich. It implies a struggle. I think all artists identify somewhat with awkwardness and being a little outside the main stream. Maybe that’s why they originally became an artist.

A: On a different note, has having children changed your work at all?

K. I’d say being around children can bring out your sense of play and your sense of the absurd. It can also make you really value your work because when you are raising children your time to make art can be quite limited.

A: what did you study in college?

K: Art history and political science, so I came to making paintings later in life. I imagine that being an art student must be a lot of fun and I regret missing out on all of that. But there are many ways to become an artist. Maybe the most important thing, and I think many people would agree, is to surround yourself with a community, be they poets, musicians or visual artists and hopefully these people will keep you working and keep you honest and true.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview with Matthew Ronay

Installation view:

It Comes in Waves

Nils Staerk

Copenhagen, Denmark

September 1 – October 20, 2012

(*)(*)(*)(*)(*)(*)(*)(*)(*)(*)(*) Dilation Levels 2011 Walnut, basswood, lamb leather, cotton, steel, dye, shellac-based primer 74" x 77" x 38"

Observance 2007 - 2008 Walnut, sapele, clear pine, plaster, silk, plastic, leather, newspaper, polystyrene, paint and vinyl glue 96 x 180 x 47 inches

Front: Harvester 2011 Walnut, basswood, purple heart, cherry, ash, lamb leather, cotton, duvetyn, steel, dye, shellac-based primer, latex paint, cinefoil, plastic, wire, lightbulbs 108 x 56 x 25 inches Back: Abacus/Seed Pod 2011 Walnut, leather, cotton, shellac-based primer 78 3/4" x 64" x 74"

Eleven Levels Of Ecstasy 2011 Basswood, duvetyn, lamb's leather, steel, shellac-based primer 35 x 55 x 22 inches

Matt 2011

Walnut, basswood, lamb leather, cotton, steel, waxed cord, plastic, wax

26 1/4 x 45 x 49 inches

detail: Harvester 2011 Walnut, basswood, purple heart, cherry, ash, lamb leather, cotton, duvetyn, steel, dye, shellac-based primer, latex paint, cinefoil, plastic, wire, lightbulbs

108 x 56 x 25 inches

Virile Bleeding Horns / Menstrual

2011 Purple heart, basswood, lamb's leather, duvetyn, plastic, steel, dye, shellac-based primer 81 1/2" x 61 1/2"x 18"

Installation view:

is the shadow

Marc Foxx

Los Angeles, CA

September 12 - October 17 2009

Tabletop Arrangement 2002 MDF, wood, paint Dimensions may vary: 9 3/8 x 28 x 13 inches

detail: Emerging Pod 2011 Basswood, purple heart, birch, lamb's leather, electric wire, lightbulb, steel, duvetyn, shellac based primer, dye 129 x 102 x 48 inches

detail: The Tone 2012 Basswood, white oak, ash, plastic, dye, steel, cotton thread

40 x 38 x 15 inches

Repeat the Sounding

Luettgenmeijer Berlin, Germany February 23 – April 13, 2013

The Tone 2012 Basswood, white oak, ash, plastic, dye, steel, cotton thread 40 x 38 x 15 inches

detail: Luring Bells 2012 Basswood, purple heart, cotton, plastic,steel, dye

283cm x 49cm x 15cm

Portal Probed By Wand Terminating In Turquoise

2012 Basswood, purple heart, cotton thread, plastic, shellac based primer, dye, steel 129cm x 93cm x 47cm

Mountainscape Orifaces/Portals 2012 Basswood, dye, shellac-based primer, steel 59 x 78 x 31 inches

Nighttime Counting Standard

2012 Basswood, suede, cotton thread, plastic, foil, shellac based primer, dye, steel 172cm x 92cm x 38cm

detail: Nighttime Counting Standard 2012 Basswood, suede, cotton thread, plastic, foil, shellac based primer, dye, steel

172cm x 92cm x 38cm

detail:

Nocturnal Tuft With Testis 2012 Basswood, suede, cotton thread, plastic, dye, steel 179cm x 81cm x 70cm

Artist working in studio

detail: Portal Probed By Wand Terminating In Turquoise 2012 Basswood, purple heart, cotton thread, plastic, shellac based primer, dye, steel

129cm x 93cm x 47cm

Luring Bells 2012 Basswood, purple heart, cotton, plastic,steel, dye 283cm x 49cm x 15cm

Nocturnal Tuft With Testis 2012 Basswood, suede, cotton thread, plastic, dye, steel 179cm x 81cm x 70cm

A: What is your process? I notice in your earlier work the objects were toy like and very pristine - were those all handmade?

M: Yeah, everything I do is made by hand. I use tools but nothing is cast or anything like that. It was all MDF for the most part.

A: Is that labor intensive process a form of ritual?

M: I’m a really routine oriented person. I gain a lot of strength from my routine. Even the process of getting dressed to do certain kinds of work can be ritualistic; but, I think for me, depending on what kind of process I’m doing - if it’s a really repetitive process than I definitely get into a trance in order to endure the repetitive nature of the process. I don’t know if it’s so much ritual as it is meditative. Thoughts are flowing in and out of my mind while i work; but, I’m not dwelling on whether they are good or bad.

A: They just are what they are.

M: Yeah, I think a lot of the processes I use are now processes. They are not based on the future or the past - it’s just watching wood disappearing or something. I think with drawing I have a similar approach - you can call it doodling but I think it’s more of a process of watching something unfold and not judging whether its going to become something, like a great sculpture or finished drawing, or something that gets thrown away. Its a nonjudgemental area.

One kind of ritualistic aspect of working with tools is that tools have a tone. Like the same way that if you use the sounds of a bowl or a bell as a tool to meditate. Particular tools have a tone as well. As the tool touches the material it slows the process down and you get in this weird zone based around the tones and the tools.

A: That’s so great to think of the tools as a melody.

M: One process where you can see it happening is this particular piece that was made by creating lines back and fourth and back and fourth. As the tool goes down it creates this weird sound - some of my studio mates say it sounds like a lamb crying. It has this weird quality that it gets you into the zone and I find that comforting as the day passes. Especially if you have to do a lot of a particular kind of thing, maybe in the beginning you get a little panicked because you’re thinking “oh my god I have to fucking do three weeks of this” But then somewhere in the middle you build up a lot of strength.

A: And then you even look forward to the task.

M: Yeah. I think for me what is important about the handmade, I’ve heard this said, is that if you use a tool, not necessarily an art tool - maybe even like a pair of scissors that is made by hand, you are almost participating with the person who made it. For example, you can have a really nice handmade knife and as you’re using it you participate with the person who put their love and care into making it, while you’re putting your love and care into using for your own purpose.

I think its also true for art made by hand. Certain ideas benefit from some distance between the maker and the thing made; however, if your goal is less intellectual/theoretical and more intuitive and emotional than I think you can really benefit from a process where it takes all your energy, time and desires to make something. So when you experience looking at it, you bring what you bring to it as well but you feel the energy transference.

A: I want to go back to something you said about drawing - I am kind of blown away by having the ability to just let something be. Have you always been able to let go like that?

M: For one thing, when you work in a small sketchbook there is a lot less commitment. The commitment that it takes to make something good or bad is minimal in this form. So as you go from page to page you don’t feel like these pages ever have to come out of the book and be viewed by someone else. I think the physical form of a book is nice, if you don’t like what you've done you can just turn the page. If you can find a style that allows you to get your ideas onto the page quickly you can make 100 drawings in a day and you’ll probably have at least one good one. I think all forms of practice are based on the idea of failure. For example with happiness or fulfillment or spiritual completion a lot of people have the idea that there is a magical thing that will make you happy - a lot of consumerism is based on that idea. But the thing is with practice its 70% failure and that is what life is. Of course sometimes you succeed, but when you do you should know you’re going to fail again. And when you fail you should know that you can have another chance to succeed. I think drawing really encompasses that idea. All practices are based on that idea, it’s called practice because you don’t always get it right. You just have to believe that you’ll eventually get something right.

T: Do you show that part of your work? Are the failures a part of it or do you just focus on the finished piece?

M: I always try to have a little bit of ugliness within the beauty. I think it helps within a piece to have a contrast between the failures and successes. But for the most part I share what I think is most successful with the work. In the earlier more cartoonish work, the sculptures were almost replicas of the drawings. And when I changed my work I allowed the process to dictate a second round of decision making. I sometimes think the work gets more raw and less controlled. As I continue to work, especially when I’m cutting wood a lot of the times I’m trying to make this one shape, and then that piece that falls off the machine and I’m left with, this negative shape, and I find I’m usually really attracted to that piece. This isn’t exactly a mistake, but it wasn’t my intention. I think creativity always works that way. Its similar in terms of looking at yourself. You build up an idea of who you are and then you’re denying this whole other side. But if you could somehow step outside of yourself and look at that part you’re trying to ignore you might realize that it actually has a lot to do with your actions and views. I think it’s a good analogy for a lot of things.

A: A lot of you’re forms are reminiscent of forms from nature, some of them look like they could be homages to mountains for instance. I know I keep on coming back to the idea of ritual; but, I’m curious - what is the relationship between someone living in New York City, in the 21st century to nature or to spirituality?

M: I think it’s hard in New York. I have a very isolated lifestyle. Which helps me focus. I can be social sometimes, but I don’t really go out that much. I spend a lot of time in my studio by myself thinking and working. I think that isolation gives me a tiny bit of perspective on myself which is what spirituality is to me. Even if you practice in an organized way, I think the relationship is (or should) always be personal.

In terms of nature, I think it's really difficult. I often think about how a lot of artists in recent history have had a country house or some kind of retreat. I think being alone without being lonely is really important to the creative process. To be comfortable to be by yourself and not feel like you need someone else or an idea as a scratching post and to just be alone with your thoughts is really important. I isolate myself a little bit to get that but it can be hard in New York.

But with these kinds of mountain shapes to me it can be read many different ways. I can see a mountain or a setting sun. But, I also see these as orifices: like eyeballs and tears, or nostrils and mucous. I think that’s true in nature though too: a single image or form can have double or triple interpretations, really it can be infinite. As they multiply out and get bigger, they also get smaller. Like the Eames movie the Powers of Ten. As far as you go inward to see the veins and vascular networks, and then go out to see galaxies you see that everything mimics itself. From the smallest cell to the largest universe everything has similar geometry and balance. While it would be nice to have somewhere I could go to be with nature more, you can see the natural sense of order without that.

A: It provides a really great sense of comfort to think that what is outside in the whole universe can be found right inside yourself.

Can I ask about your relationship to color?

M: Well, I’m colorblind. I’m red green color blind, so anything with red or green is difficult to put a word to. I often have to ask someone “is this purple?” When I use color, like now I am using a lot of color but I go though periods where I don’t use much because its difficult. For that reason I tend to use a lot of saturated colors because they are easier to see. My relationship to color is complex, but I feel like it gives me a lot of respect for it. I think everyone sees color differently though. A lot of scientists are saying we aren’t actually sure what color is outside of our own minds.

I went through a 3-4 year period where I would only use the color of the material. Like purple leathers, pink or dark woods, things that weren't painted I should say. I really enjoyed that because I didn’t have to think about the color so much. But as much as you gain by having a natural or minimal palette, in terms of seriousness (like dark Caravaggio paintings that have a great weight) you lose a little bit of joy and openness of celebration - I think that’s why I brought color back.

A: There is a really wonderful lightness in your work. I don’t know if you want your work to be interacted with, but that fun quality makes the viewer want to go up and touch them or rearrange them or something which is really great.

M: When I changed up some things in my work I found that I was really attracted to works that are made not just to add to the discussion of art history, but works that were made for ritualistic use or just use in general, like maps, or a costume or musical instrument. Most of the things I got really excited about were things that people had to make because they were useful. I can’t necessarily make that kind of work because I don’t belong to that kind of longstanding tradition. When I use ritual or spirituality its fantasy based. Objects that are useful have a lot more weight than objects that are made just to add to the discussion of art - for me, anyway. Like a daybed by Donald Judd does more for me than the things that he’s more known for. Not to say that design is higher or better than anything, but there is something very personal about use that adds something.

A: I also love when utilitarian objects were crafted with a certain aesthetic. I feel like it shows that beauty has a use too. It’s weird because art is unnecessary and extravagant, but it’s something that people have never lived without.

In terms of language - do you see your objects as symbols or words?

M: At different times different ways. Sometimes I can interpret a work almost forensically like I look at it and think “this maybe means this when it’s in line with this” but that can be really tiresome. My goal with making things is to experience new thoughts and crack myself open. I think that if you expect to be able to explain your work when your are finished making it than there is non leverage to crack yourself open because you are just staying at the border of your mind. On one hand, I think if you want to infect someone with your disease it’s more effective to spread it with language, but visuals and symbols are nowhere near that level of efficiency. That kind of misunderstanding and slippage is one of the great things about making art - language is sort of the same way, but we can agree more on what words mean.

A: Is your process a method of escaping something or getting closer towards something - of course it can be both, I’m just curious how you see it?

M: It’s hard to say. I depends on my frame of mind. But if we open up the concept to be outside of me, personally - I like to think of it in terms of a witnessing, objectiveness. I don’t think of it as escaping as much as witnessing something happen. That doesn’t mean you don’t experience it - it just means you experience it without judgement. The reason why a lot of works I’ve made over the last couple of years have a mystical quality is because I feel lacking of that mystical quality within myself so I’m trying to create it. I feel disconnected and am looking to connect.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview: Elisa Lendvay

Conversation between One of Our blogs' founders, Ari Eshoo and artist, Elisa Lendvay.

http://elisalendvay.com

Tumble Brush Dirt (2009).

Sham (2007).

Drift (2012).

Chulel (1998).

A: I noticed that your objects’ surfaces and colors have a sun-bleached appearance as if they’ve been tossed in the ocean and washed up on a beach. I’m wondering if where you came from has any effect on your work?

E: It definitely does. I grew up in Texas with a lot of intense sunlight. And I’ve also spent a lot of time in desert landscapes and just outside in general. I’ve always been aware of how the elements can whether things and fade color. Actually, many of the things in the home I grew up in got sun bleached through the windows, including some of my own older art there that is almost now invisible. Also growing up in proximity to Mexico, I think the colors from that country have always interested me - faded murals on buildings. I think I intuitively find objects that have those faded colors and often work within that pallette.

A: Do you think of your sculptures as landscapes in themselves or are they more like artifacts from the landscape?

E: That’s interesting. Sometimes I see them as topographical landscapes and microcosms; especially some of the smaller pieces. I have thought about it that way - but i also see some of the forms existing on their own, and they could in a sense be a part of or within a landscape.

A: You place objects in such a way that they form groupings like cliques; other times they seem more distant - like friends losing touch. I’m wondering how you see human relationships. Are we essentially alone or are our relationships genuine?

E: I don’t try to specifically answer to that in my sculptures; but i think about that quite a bit. The pieces often do become these kind of personified entities. I’ve found that sometimes when I’m doing installations and I have a larger space to play with I really play with these kind of groupings. Since these are awkward, physical forms it’s almost easy to address issues of isolation or acceptance within a grouping, through placement. I’m always thinking of relationships and the body and what it means to be alive and physical in space.

A: There is definitely a certain sense of anxiety in relationships of any kind. You can know a person so well but really never truly know what they are thinking or feeling.Everything is so fragile and built on these precarious foundations. Even though I of course do have close relationships with people; I often feel like everything is in a state of perpetual flux because there is such a strong but delicate veil of emotions around everyone.

E: And there are these kind of philosophical questions that come in and ideas of perception and reality. Like trying to understand what other people might be thinking or feeling and who you even are. That always there. I think for me my art does try to answer some of those questions. Getting into that internal space of making, solving problems through process and formal issues; as your wrestle with material and ideas sometimes these things get answered or sometimes they just make you aware of your doubt and uncertainty. I was always very close to my family, very creative with my brother and sister. Although I moved around a lot, I was never trying to leave. Art can serve as a metaphor for figuring out who you are and who to open up to.

I’ve had I often have these pairing or clustering of random fragments. There are often different kinds of pairing and parts of wholes. I think about creating spaces with my forms but also having these self-contained objects. I’m always playing with relationships. and often the studio space becomes a big installation of all these forms because of economy and space; but when I separate them they have their own existence and a breath all on their own.

A: I notice that in Abacus it really looked like a whole universe in of itself. Is that a metaphor for an internal universe?

E: It could be - these parts within one structure that can move around and have their own life. I was thinking about the solar system and collections and pairings of things. The ideas that I faced when making abacus are still things that come up in my work, especially in these nets I’ve been making, its a way of suspending forms, and connecting disparate objects, made or found. I collect and connect objects in relationship to color scheme, tactility or materiality.

A: also just the name abacus, obviously has a connection to math. I find that interesting in relation to art. There is such a beautiful precision in the world - if everything wasn’t the way that it is - nothing could be. I think that is incredibly beautiful and in a way that precision invigorates me with a reason for being and gives such a great sense of purpose. I think math and science actually have a strong relationship to art. There is a certain precision in art even though for instance a DeKooning may seem chaotic – each stroke is precise and specific. Your work has a sense of specificity in terms of place, color and relationships - what are your thoughts on that?

E: Well, I think systems, the universe, geometry fascinates me, and it does make you wonder about all of the precision in how we are made and the world around us. It makes you wonder if that exists in the relationships and all the randomness of everyday life and what is meant to be. And in the studio, it’s like when you’re making things you’re kind of tapping into a deeper understanding of the way that things fit. And even though it‘s all your decisions, you’re all the more allowing intuitive things to happen that make sense and is specific by the act of letting go.

A: How do you approach the specificity of form in abstraction? To me they seem like they are abstracted from memories - like something that you are trying to piece together while its already wet and slipping through your hands as your trying to recall it. Or are they based on observed bodily representations?

E: They come from all sorts of things. I think about memory and time - I’ve been using my process as a metaphor for that. Like the strata of material or the repetition of form that i made in wire repeating itself like tree rings and growth. How someone can be so small and large. Or the echo of someone being in one space and not being in that space anymore. I think about the evolution of a moment and how I can represent that through forms. But I always go out to be in nature or people watch - I’m very observant and I think as artists we are porous and always trying to digest and do something with what we see and feel - I think that comes into play while thinking about abstraction. Also body memory. I’ve always danced and am very active, with a need to really move through space; I’ve realized that my forms sometimes look like the lower half of my body - like what the legs do in terms of weight and gravity -bending, arching, or in ballet, a plie or tendu. I’m realizing more and more that the body has a strong presence in my work and that leads to some narrative readings. I think I also develop my own languages I go in making work by repeating certain forms. Sometimes I’m specifically looking at things from everyday life because I think thats a healthy thing to do. I think i’m always starting from something but it gets very removed during the process. Then other times the material leads you to the form and you respond to what you make. But since I sometimes use found objects, I find these forms based on how they look and how they are weathered, and then respond to that.

A: I’m struck by how you brought up body memory. It makes me think of the way athletes improve partly because their body remembers how to move or hold their bats or gold clubs a certain way. The hand remembers.

A: What is your studio practice like? Do you work everyday?

E: Ideally its an everyday thing. I’m realizing this winter I’ve been working at home more at my kitchen table. But I sometimes ride my bike to the studio, or take the bus or the train - its close yet, far. I like my studio because of the way the light comes in. But its a beast of its own because its not quite working for me - i need a bigger space. And there are some basic logistics. I started teaching more classes than I normally do at Montclair state, so it depends on my routine. But i tend to make or think about ideas everyday. This winter has been a real thinking time for me. And the way I work I need quite a bit of energy. There is almost a burst of things that happen and I work on multiple things at once - small sculptures and drawings or larger sculptures. Lately I’ve been dividing my time between working in the studio and home.

A: There is something really nice about working from home. It’s intimate. There is something nice about seeing the piece in a home. I find that sometimes when I walk into a gallery I’m very aware of that cold space - for instance even if the work is great I can’t get lost in it because I cant disassociate the work from the white walls or someone making sure i’m not breathing too hard on the work. But some work really transcends and I wonder if that is affected by where the artist works. Like seeing the object you’ve made in relation to your chair or a coffee cup.

E: I think there is a strong relationship to where the artist works and the outcome. I’ve talked together artists about this. There is a period where I had my studio in my home and when my boyfriend was gone i would spread out everywhere and use every surface to work on including the ironing board. I had a few people over to the studio then and this one person really responded to how the work existed in the home. I had this library bench next to the couch with small sculptures on it in some sort of Freudian congregation. I had a sculpture next to my bed and it ended up becoming my nightstand. And i had an earplug left on the sculpture one day and it ended up fitting in this little nook in the sculpture - and that just blew me away! I kept it there. Then there was a period where I had these human scale sculptures and I took photographs of them in the apartment elevator. Like this experiment imagining they had a life of there own.

A: Like happenings in a way.

E: Yeah. There’s something exciting about that. Working at home is exciting and cozy. It’s a place where art and life can coexist more intensely.

A: There’s a certain level of guilt I feel sometimes in making things that are...essentially useless so its interesting to turn a sculpture into a nightstand or just seeing how we live with these objects.

E: I put that pressure on myself sometimes too - like “why am I making more things in this world?” but people have always made things to understand the world. Think about cave paintings and these rituals of beautifying the home. We need something physical to understand the world around us. I think as long as you're kind of aware of the materials you’re using I think its a poetic and important act to make. I see artists as kinds of shamans. Like experimenting beyond the conventional world and beyond consumerism. Even though there is a strange art structure system around money that doesn’t really make sense. But the pursuit of being an artist is different than the market.

A: It’s related to but more than tagging graffiti on the table. Yes, its leaving your mark and putting your little footprint in the world but in a way its also for the artist his or herself. Its more than a fossil because it lives with the artist - and... I don’t know if ii agree with what I’m about to say but its almost going to...die with you.

E: In a sense it does. But it still remains physically. You

know over the years one of my many odd jobs has been working at an artist’s estate with the wife of someone who is maintaing the estate and the art and the provenance of the pieces and the people who've purchased them - its so intense. And i think about that - if I’m not here anymore what will happen to the work? Will it be a burden to someone? That’s a whole other strange thing. Its something you always have to keep in check.

A: did you start out painting and drawing?

E: yeah, but always wanting to do more. even in high school. making wall reliefs and sculpture. But in college I just couldn’t allow myself to just paint though I loved it. I was questioning things. I thought i had to do something more - that painting was too simple. stretching canvas on a surface, I just had to go beyond it. I related to Luciano Fontana, before I even knew about him, opening through the canvas getting to the space beyond the wall. just all those other relationships around the space of a painting, in addition to the painting, are so important to me. But now i think when i make a painting its all the more informed by the way i’ve questioned it. But I’ve also wished I was just a writer sometimes so i wouldn’t have to deal with these issues of the physicality of the things I make - there’s a responsibility and it’s not easy.