Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

ASOS: A Surveillance Of Size

ASOS (AsSeenOnScreen). Where do we begin?

If you were like me, it may have just been brought to your attention that ASOS can be translated into this acronym. In fact, many customers of the brand are not aware of this.

ASOS is an online British fashion and cosmetic retailer, which was founded in 2000. Selling around 850 brands and shipping to over 200 countries worldwide.

For me, ASOS is my holy grail online shopping outlet. If I’m bored? You’ll find me scrolling through ASOS. Distracted in a lecture? (shameful, I know). I’ll probably be weeping at the expense of all the items in my ‘saved items’ list. In desperate need of something to wear for a night out? ASOS will sort me out, for sure. And the wedding I haven’t been invited to yet? You’ll always find me admiring the pretty dresses.

What I love about ASOS is that they have such a broad range of clothing, from swimwear to fancy dress inspiration, and even HOMEWARE. You can’t go wrong.

I suppose I could be described as a ‘serial scroller’ when it comes to online shopping. An innocent addiction which quite frankly my bank account takes the hit from. Time. And. Time. Again.

It is almost like ASOS knows how much I want that new summer co-ord with pretty flowery detailing from the latest “summer range drop”, saved in a size 8. And I suppose they also know how many times I’ve put that sparkly pink jumpsuit into my basket, and how long I spend staring at the total before coming to the conclusion that maybe, just maybe, £150 is too much to spend on one item of clothing that I’ll probably only wear once, and then Depop later in the year.

You mean they do know?

Damn right! Your edit is where we have put together a collage of your top pics.

You mean they purposefully target my Instagram and Facebook feed with my saved items (or similar) in order to entice me to go back and purchase them?

Oh yes. Subtle, right?

What about my sizing? Surely they haven’t got that figured out too?

Correct! We know you usually fit into a size 8 in tops, an 8 in trousers/skirts and well, jumpers? 12-14. We know you love them oversized!

So, what you’re saying is, I just need to enter my details of my preferred payment method and that’s it?

No way! We aren’t time wasters. We’ve remembered your card details from before (and your boyfriend’s, just in case he ever feels like being extra generous again). No faffing around here.

If you think you’re that smart, what about my delivery address? This girl travels…

No problem. So, you’re normally in Reading, right? We mainly deliver there, but it seems your impulsive purchasing isn’t just restricted to Reading. Because of this, we’ve saved your home address for these occasions. Oh, and when you’re desperate and no one is home. Your mum’s work isn’t shy of a few parcels every now and again, is it?

As demonstrated in the narrative above, ASOS are well and truly the experts at keeping check of our online shopping activity. However, it is important to use the phrase “keeping check” loosely, as the proper term for this type of behaviour analysis can be defined as “surveillance capitalism”. By storing information such as our addresses, card details and most frequently searched items, ASOS is able to create a more efficient process of online shopping for its consumers, meaning that online shopping can be as easy as 1 (finding the items you like), 2 (purchasing these items), 3 (having them delivered to your doorstep).

Lehtiniemi (2017) outlines that “surveillance capitalism encompasses mass dataveillance”, which aims to “regulate and govern” behaviour of individuals engaging in a specific platform, such as the likes of ASOS. Within this platform, technology developers have the power to turn people from “data sources” into “active data subjects”, however at the same time promise to “empower people to take control of processing of personal data”. Here, it could be argued that it perhaps isn’t the case that customers of ASOS are in control of their personal information, in the way that this information is extracted in order to manipulate the routine behaviour of its customers through “targeting” and “personalisation”. Despite ASOS encouraging its customers to give their personal information away in order to receive a better service, ultimately, this is a “profit-turning” exchange which benefits the back pockets of the technology developers within ASOS. This digital economy therefore extracts any personification of these individuals, essentially transforming them into “quantified data”.

So, when we receive emails such as “happy birthday! Here’s a 10% off code” or advertisements on our Facebook feeds, could it be argued that at this point we are no longer viewed as human beings behind a screen? Or a respected customer of ASOS? Are we just contributing to the database of numbers? Numbers which contribute to the “datafication” as well as their profit margins?

When ASOS revamped their website in late 2018, personally, it came as a shock to me that out of nowhere, ASOS seemed to know my sizing, and this fluctuated for different types of clothes, so I was impressed that it could recommend all these different sizes. However, what baffled me the most about this concept was that I had never given ASOS any of my measurements. But this was the thing. It was then that I realised that ASOS was pretty much guessing my size on each occasion, and it just happened to be that 9 times out of 10, they matched the size I would most likely buy. UNTIL… when writing this, I checked again.

So, you want to buy this dress?

Let’s say you’re a new customer to ASOS. You haven’t ordered from there before and you average around sizes 8-10 in most items of clothing. You aren’t aware that in order for this sizing match feature to be most effective, you need to enter not only your ‘tummy’ measurements, but your bust, waist and lower hip (whatever that’s supposed to mean). However, you are often very conscious of your body shape, regularly feeling like summer clothes like this will look silly on you. Nevertheless, feeling confident that you can definitely rock this look, you click ‘add to basket’. But not too fast! Before ASOS holds this in your basket for you, you are faced with a size recommendation. Oh, a size 12. You’ve never bought a dress in a size 12 before and you feel slightly bemused. You love things to be oversized, but not a DRESS? This knocks you back even further, resulting in you feeling even more body conscious than you did before.

This can be deceiving until you enter your personal details. As someone who doesn’t keep track of their weight, when entering my details to demonstrate this feature, I was surprised to feel extremely vulnerable. Who is seeing this information? And how will it be used?

And this was the outcome...

The point I am trying to make here is that this feature can either make online shopping a hassle-free, more efficient process, or alternatively in some cases, a very daunting and humiliating procedure. Here’s why. In today’s society where women and men often find themselves being defined by their appearance, I was left feeling what I can only describe as frustratingly stunned when Victoria Secret welcomed Barbara Palvin as their new ‘plus sized’ model to their ‘Angel’ community.

You can make a judgement for yourself about whether you agree to this label of ‘plus sized’.

Although an extreme link, which may only apply to very few of ASOS’ customers, it is estimated that 1.7% to 2.4% of the world’s population suffers with Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD). That’s 1 in nearly every 50 people. This disorder is characterised by negative thoughts about one’s perceived flaws, which burdens them every day. These thoughts have potential to interfere with the daily functioning of one’s life, leaving them feeling extremely distressed, often resulting in isolation from friends and family in fear that people around them may notice these ‘flaws’. However, the reality of this disorder is that no amount of convincing or reassuring can encourage someone to believe that these thoughts are irrational, and that no one else is thinking the same as them.

So, despite ASOS asking for your age, your height and your weight, with the innocent intention of improving your online shopping experience through a more personal approach, why can shopping online now feel as though we are having a routine check up at the doctors every time we sign in? Is it essential that ASOS withholds all of this information about us? It is unearthly that a computer calculates these numbers every time we want to do some shopping?

I took to Twitter to see what people thought about this new size recommendation feature, and this is what I found:

What do you think?

Has this sizing feature hindered or enhanced your shopping experience with ASOS?

References:

Lehtiniemi, T. (2017). Personal data spaces: An intervention in surveillance capitalism. Surveillance and Society, 15 (5), 626-639.

Cherrington, R. (2017). ASOS Is Guessing What Size Its Customers Are, And They're Not Happy About It. Retrieved from: https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/asos-size-recommendation_uk_58871c69e4b02085409924c3

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

No offence, but...

youtube

You may say this two, maybe three times a day without actually thinking about the statement you’ve followed it up with. For example:

No offence, but�� I think I should drive.

No offence, but… I prefer the other outfit.

No offence, but… maybe it’s best you order a salad?

You could argue that these are much more subtle ways to approach being honest with someone, without hurting their feelings, but what purpose exactly does “no offence” serve?

I remember in my primary school days, saying “no offence” was by the far the sassiest thing you could say to someone, in which you would almost certainly cause offence. Of course, this would only be about something petty, like, “no offence, but my mum makes better packed lunches than your mum”, “no offence, but I don’t want to play with you today”, or, “no offence, but my mum said you’re not allowed to come for dinner because you’re a fussy eater”. However, the age to which we used this discourse marker spoke volumes. What we were saying didn’t elicit any permanence to these friendships in school, probably because they were my friends and more often than not, the next day everything would be right as rain again.

However, is it fair to say that social media has changed the “no offence” game?

Now? Using “no offence” seems to have people under the illusion that using this before insulting someone softens the blow? Countless times I have seen trolls commenting on celebrities or influencers’ photos stating their unwanted opinion, proceeded by “but no offence, yeah”, as if this is a justification to be rude. It is almost certain that celebrities, such as the likes of Kim Kardashian or high-profile figures like Donald Trump, will not take personal offence to these comments. Not an eyelid battered. So, in that case, if the sole purpose of trolling is to cause offence, why are trolls hiding behind this shield?

Is there a desire to always appear polite online, even in situations when we have intentions to be rude? What about when we DON’T have any intentions to be rude?

Perhaps this is a similar concept to teenagers smiling at elderly people in order to reassure them that they’re not complete and utter thugs?

However, not only has social media opened a gateway for people to be outwardly rude to other social media users, it seems that social media has created an army of sensitive souls. Why is it that we like to take offence to almost everything? We all know that “sticks and stones may break our bones but words can never hurt us”, but what about the power of a photo? Are children growing up in today’s society being taught strategies to avoid taking offence to everything they scroll past? Let’s be honest, they won’t be throwing sticks and stones, they don’t play outside anymore!

Let’s give it a try, which of these images do you find the most offensive?

1. Kim K posing in the nude on Instagram?

2: A pug in fancy dress?

3: Women belong in the kitchen meme?

4: Theresa May impersonating Pinocchio?

Even if you didn’t take offence to any of these images, someone, somewhere in the world would have. But why? What triggers someone to take offence?

The “foundations of morality” could help explain this a bit better. Parvaresh states that although research has demonstrated that “our actions, behaviours and judgements are ‘situationally constructed’, they are also ‘morally informed’. This therefore suggests that what leads us to take offence to something is encouraged by a “set of expectations” proposed by society based on a “coherent set of notions of what is right and what is wrong”. So, this is fairly self explanatory; if someone believes that Kim K posing in the nude for her 130 million followers is wrong, then this opinion is based on the ideals and assumptions that they think other members of society should abide by. Their moral reasoning could have originated from any of these moral judgements:

For example, if we were to go through the list:

Image 1:

Fairness and cheating could be one of the underlying reasons as to why someone may think this is offensive. A mum of the same age as Kim may strongly believe that Kim has cheated the system of motherhood. They do not think it’s fair that they have achieved such a perfect body after having 2 children.

Image 2:

This as offensive due to potential concerns of any harm brought to the dog during the process of it being photographed. Extreme ideals may believe that this is a mild form of animal abuse.

Image 3:

Degradation. It doesn’t just take a feminist to agree that this attitude is outdated in modern day society.

Image 4:

This photo-shopped image of Theresa may ultimately undermines her leadership and what our government stands for. Here, someone is likely to take offence if they hold views that authority should not be mocked.

SORRY, NOT SORRY...

But what about this? Is this the sort of sass today’s kids are using? OR, is Demi Lovato to blame for this one?

I suppose it’s no secret that us Brits like to be over-the-top polite, throwing “sorry” around like its confetti. We love it. It makes us feel good. We like to let strangers know we’re sorry, even if we’ve got nothing to be sorry for. Trying to get past someone in a busy aisle in Tesco? You say sorry. You’re early to a meeting? You will probably apologise. You apologise to the homeless man you pass on the street for having no change, and you apologise at least 3 times to the man from the call centre when you say you’re not interested in their car insurance deal. We can’t help ourselves.

But what does “sorry, not sorry” mean? We’re sorry for not being sorry? Why are we apologising for this? Again, this is another example of being over polite, even in contexts where we do not need to justify our behaviour. So, is “sorry not sorry” the new sorry? Is it now more appropriate to say “sorry, not sorry” when someone bumps into YOU in the street, or when you get to a car parking space before the person behind you does?

UNPOPULAR OPINION: Are we becoming too sensitive?

If you’re an avid user of Twitter (some may say with a good sense of humour), tweets that start with “unpopular opinion:” are COMEDY GOLD. Inserting this before giving your unpopular opinion essentially justifies this opinion. By letting everyone know that you are aware that this may not sit well with everyone you follow, you have bagged yourself a “get out of any controversial debate” FREE card. For example:

Someone tweets: “Unpopular opinion”: IKEA is overrated.

As someone who LOVES IKEA, I take offence to this. BUT, because this person acknowledges that not everyone will agree, they have therefore stripped me of my entitlement to take offence. So, it is almost like “unpopular opinion” is the modern day version of “no offence”.

So, what measures need to me taken in order to avoid causing offence online?

It is necessary to consider how your language/interactions online resonate with others, and more importantly how your beliefs and opinions may not universally match the beliefs and opinions of those you follow on social media. Although it is crucial to be mindful that there is permanence to what you share online, on the other hand, I believe that there is nothing wrong with sharing the real ‘you’ online. Whether that be sharing your opinion on your favourite chocolate bar, or how much you love a particular football team. Regardless of what you post, not everyone will ‘like’ it on Instagram, ‘share’ it on Facebook or ‘retweet’ it on Twitter.

So, the 2012 days are over, where “no offence” belongs! This is 2019. If you’ve got something to say, be OUTSPOKEN, be BRAVE. But make sure you begin EVERYTHING with “unpopular opinion”, just in case. Also, don’t forget to sign it off with “sorry, not sorry”. We don’t want anyone to throw their toys out the pram, do we?

youtube

References:

Barrow, R. (2005). On the duty of not taking offence. Journal of Moral Education, 34 (3), 265-275.

Parvearesh, V. Forthcoming. Moral Impoliteness. The Journal of Language Aggression and Conflict.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snowflake or sNOdrama?

Apart from the obvious definition, in the social media world, the definition of ‘snowflake’ has been redefined to refer to “an overly sensitive person” who ultimately believes they have the “right to be protected from anything unpalatable”. With the term deriving from the phrase “special snowflake”, used to refer to anyone who is easily offended and is unable to deal with opposite opinions, it appears that social media is becoming a breading ground for these “snowflakes”.

In recent news, it seems that celebrities often find themselves in the firing line from snowflakes, whether that be because their tweet was too controversial, or their Instagram post breaks the ‘so called’ defined “social norms” and “expectations” of what is acceptable to post online.

How could multi-modality have a role to play in all of this?

“IF A MEANS FOR MAKING MEANING IS ‘MODALITY’, THEN WE MIGHT SAY THAT THE TERM ‘MULTI-MODALITY’ IS USED TO HIGHLIGHT HOW PEOPLE USE MULTIPLE MEANS OF MEANING MAKING” (Jewitt et al, 2016).

With multi-modality being defined as “the use of multiple semiotic modes, such as visual, aural, spoken and written communication, in a text to create meaning”, is it fair to say that snowflake behaviour is the product of “meaning” no longer being shared amongst a specific online community? Do the lines become blurred between being creative online and causing offensive?

Stacey Dooley is one celebrity in particular who knows all too well about the cultivation of snowflake behaviour online. More importantly, how a simple miscommunication of meaning on one Instagram post in particular lead to such misfortune.

How would you interpret this photo? What is your first thought?

My thoughts:

1. Being renowned for filming documentaries in third world countries, it is not out of character for Stacey to be pictured in this setting.

2. This Instagram post was a way for her to express her gratefulness to be invited out to Uganda in order to raise money for Comic Relief.

3. A very raw and natural photo (she has been stripped of the glitz and the glam (unlike the photos shared during her Strictly Come Dancing journey).

4. By captioning the photo “OB.SESSSSSSSSSED<3”, it appears that this child holds a special place in her heart. A child she has met during filming?

5. A very ‘real’, genuine photo. Sharing the relationship she has built with the members of the Ugandan community.

And the media?

1. Labelled as a “white saviour”. This photo comes across as boasting about her opportunity to rebuild the lives of those living in underprivileged Ugandan communities.

2. A child was chosen for this photo to entice greater sympathy from her audience. She had simply whisked this child off their feet, taken the photo and then walked away.

3. “Look what I’m doing, isn’t this just wonderful”

4. She believes she is “helping” a community without fully understanding the history or causes of the poverty.

5. She is painting herself as an educator.

6. This photo promotes “poverty porn”. The caption describes a likening to a new pair of shoes. Such language should not be used to describe a child.

7. Of course the child isn’t looking at the camera or posing. This child does not know what an iPhone is, let alone a “selfie”.

8. Privileged white woman attempting to play the role of a heroine.

9. Offensive and uncomfortable.

Are the media wrong for making these assumptions?

If a judgement is there to be made, especially with the help of freedom of speech, is it fair to say that everything we post online is open to interpretation?

How can this one case of meaning miscommunication result is such animosity?

Is this an attack on Stacey for being naive? Or did she simply not take enough care when posting this?

Is it even more important that celebrities take extra care when posting online?

Do figures in the public eye immediately get more stick for their posts as a result of having a greater following? Is it harder to please a large audience?

Does this highlight the importance of considering alternative interpretations that could be derived from your Instagram posts, prior to posting them?

Let’s give it a go...

Picture 1:

My thoughts:

1. Cute?

2. A summer memory I wanted to remember

3. Witty caption - funny?

4. Dogs are undoubtedly Instagram worthy, right?

Other interpretations:

1. Trying desperately to be funny

2. Animal abuse - against the dogs will to be picked up and photographed like this!

3. Pointless content

Picture 2:

My thoughts:

1. Having a fun time - wanted to share this with my friends and family

2. OOTD? (I liked my outfit that night)

3. Sarcastic comment, emphasised by the ‘x’ - light hearted?

Other interpretations:

1. Showing off

2. “We get it, you’re on holiday” (I definitely over-posted on this holiday)

3. Annoying sarcasm

4. Stupid pose - Self- obsessed (ANOTHER SELFIE!)

5. Try hard!!!

Picture 3:

My thoughts:

1. Yummy food

2. Aesthetically pleasing (colourful)

3. Meal out with my boyfriend - wanted to document the moment

5. Again, another witty caption

6. Food is always Instagram worthy

Other interpretations:

3. Greedy! “Is all that food for you?”

4. Generic white girl photo of food

5. Uncultured - westernised South American food

6. Expensive - “So you eat out all the time?”

So, now what? What is the answer to all of this? Are we just meant to stop posting online in case there’s an off-chance that we might offend someone?

I think not.

Although it is important to think twice about what you share on online, social media sites do not come with an “everyone will approve” guarantee. I suppose that’s the beauty of being able to choose who you follow and who follows you? Despite posting the most innocent of photos, for example your dog, just like I did, there will always be someone who disapproves or has juxtaposing thoughts to you, despite the intended meaning. So, are we all doomed? Do features of multi-modality ultimately leave us feeling like we’re stuck between a rock and a hard place?

What do you think?

Is it a YES to being ‘snowflaked’ online? (do you think it is important to allow these snowflakes to monitor social media content, therefore calling individuals out for misusing social media for either being too controversial or by going against what is considered “acceptable” to post online?).

Or

Is it a YES to no drama? (Should we be free to post whatever we like online, supposing it doesn’t have intent to harm? Is it important to take what people post online with a pinch of salt?).

References:

Jewitt, C, Bezemer, J., & O’Halloran, K. (2016). Introducing Multi-modality. New York: Routledge.

Harrison, J. (2019). What does ‘snowflake’ mean, who are ‘generation snowflake’ and what’s the origin of the term?. Retrieved from: https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/5115128/snowflake-generation-meaning-origin-term/

5 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Do we really know who we follow online?

This definition was provided by a 52 year old male (parent) when asked to explain what he associated with the term ‘following’.

With the Oxford Dictionary defining ‘following’ to be the action of “coming or going after a thing or person (proceeding ahead)”, it would seem to be that he is correct. However, in recent years, this definition has been twisted and redefined by social media, now connoting the action of interacting - via liking, retweeting and sharing - with other social media users. But what about the definition of a ‘friend’? It could be argued that Facebook has distorted this definition of what defines someone as a friend. In real life? Someone who you can trust, a companion who you can relate to exclusively from family relations. Someone who can keep you company. Someone who doesn’t judge you for being you. And online? Mostly people you know, people who occasionally like your posts, but overall, perhaps people you know… but don’t really know? The girl that sits in front of you in one of your lectures? Yep, her. That guy you met on a night out who you exchanged Snapchats with. Him too. Despite having thousands of followers or hundreds of friends, could you confidently argue that your social network is a space free of judgement? Or a welcoming community which rids you of your loneliness? Perhaps not. If you were given a list of all the faces you have befriended online over the years, could you put a name to these faces you supposedly know? What criteria needs to be met in order for you to truly ‘know’ someone?

So, does this concept of ‘friending’ and ‘following’ replace maintaining relationships in real life? You meet someone once and now you follow them on Twitter, you’ve requested to follow them on Facebook, and you’ve assessed how ‘follow worthy’ they are on Instagram. You know all you need to know… and more! It makes you wonder how in the ‘olden days’ people put a name to a face. Let’s say you pass someone in the street, in your local town, minding your own business. They smile at you, and you smile back. However, you’re puzzled by this familiar face. An hour passes and you’ve searched for this face across all social medias, and hey presto, it turns out she’s a friend of a friend you met last summer. Thank God you sent this her a friend request all that time ago. Within the depths of our ‘followers’, we provide people, ultimately strangers, with front row seats to spectate our lives. The familiar stranger knows about your holiday to Greece in the summer, she undoubtedly read the twitter spat you had with one of your besties last week, and by the looks of things, she was one of the first people to watch your Instagram story this morning and knew exactly where you were off to - thanks to the beauty of Snapmaps.

It seems that an apology may be in order to our parents as those valuable ‘stranger danger’ lessons appear to have gone out the window at this point. Do we really know someone’s intentions online? What about our own intentions?

In order to get a better idea of the online networks people are affiliated with, I reached out to my Instagram followers through an online survey, and this is what I found.

When designing these questions, this result was most expected, but how can this be explained? Well, with Boyd and Ellison (2008) defining and considering a social network site to allow it’s users to “articulate a list of other users whom they share a connection”, it could be argued that it doesn’t matter who makes up this list, as long as you’ve got one. Is it not ‘cool’ to only have a few hundred followers? Or is it simply a case of social media users not being particularly bothered about who watches and interacts with their ‘content’?. So, could we agree that following someone on Instagram isn’t “all that deep”? Is a follow just a follow? But is it the connection that is the greater deal? How can a ‘connection’ be defined? For example, if a follower and I (who I have followed since activating my account in 2013), mutually and consistently like each other’s posts each time one of us uploads, is this a connection? Does having a connection with someone NEED to take place in real life, or can a connection be as effortless and shallow as liking a Facebook post?

Next up, the awkward unfollow. Some say they won’t unfollow someone, despite not necessarily being friends, because they like to “see what people are doing”, or feel they are particularly “nosey”. It was also made apparent that having “shared interests” with their ‘list’ of connections meant following someone can be sparked by curiosity and the desire to be inspired. On the other hand, it became clear that people are ‘likely’ to follow someone, despite their interests/values not appealing to them, because they “can’t be bothered” to unfollow others. Who knew unfollowing someone was such a gruelling process? More controversially, another respondent claimed to unfollow people, (even FRIENDS!!) if they were negative posters or found themselves becoming disengaged with their content. However, could it be argued that perhaps having ‘weak ties’ with other social network users has its perks? They aren’t high maintenance followers, and they open doors to other networks consisting of diverse modes of thought, without requiring you to actively expand your social network horizons. Is this a savage approach, or simply a logical way to filter and customise your feed to appeal to your interests?

And finally, can social networking sites easily manipulate its users in brainwashing them to believe they know someone through the content they post and the mutual friends they share? Let’s start by explaining this using Kylie Jenner as an example. Would you consider to ‘know’ her? You may be thinking, “but why wouldn’t I?”. She shares her daughter, Stormi, with her followers, and we know she has an extremely tight bond with her sisters. She’s dating Travis Scott, alongside owning a million-dollar beauty range. She promotes the tea she drinks, the hair vitamins she takes, and recently how her best friend created turmoil amidst cheating rumours with Khloe’s boyfriend, Tristan. So, if we know all this, is it no surprise then how invested people can become in her life, or just celebrities in general?. Are the lines blurred between an Online Network and an Online Community? Just because you actively engage in Kylie’s content, for example, liking her posts and watching her SnapChat stories, does this mean you know her? Or does this simply mean you share a common interest/goal with her and her other followers?

Perhaps we are worrying about nothing. So what if someone wants to have 3000 followers and interact with strangers every day? That is THEIR community. Alternatively, if someone else wants to have a minimum of 80 followers, and only share content online with a small network of people, then that is THEIR chosen network. But, what about YOU. No, not you personally, but the Netflix series ‘YOU’. This series outlines how social media can be used as a powerful tool in ultimately providing strangers with a search engine to your life. Through sharing your social media content publicly, you actively invite other social media users to learn all there is to know about YOU. Have you ever thought about how your friends and your followers may know you just as well as you know yourself? Have we become obsessed with oversharing our lives or is this just the norm? Maybe we all have a burning desire to be visible online? Let me know what you think.

youtube

References:

Jones, R. H., & Hafner. C. A. (2012). Understanding Digital Literacies. London: Routledge.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Digital Footprints: Put YOUR stamp on it.

It’s Monday morning. A new day. Another week of school. You turn off your alarm and head straight over to Twitter. “Monday already !!!!!!! (Crying emoji X10) Can’t w8 to get back into bed”. Your phone pings. It’s Lizzie. Your BFF. She never lets you down. Except not today it seems. “Soz bbe. Sooooo ill. Grab any hw sheets for me plzzzz (blowing kiss emoji) xxxx”. Mum shouts up the stairs “Are you getting up at any point today? The dog needs walking and you need to take your brother to school!” You slam your phone into the duvet, roll your eyes and take a deep breath. You’re annoyed and the day has only just begun. Toast in one hand and dragging your brother out the door by the other, you smile at the postman. “Morning”, you say. Knowing full well he loses your packages ALL THE TIME. Be nice mum always tells you. Manners cost nothing.

You get to school. The mean girls stare you down as you walk to your English lesson. You try to look cool. You tell yourself that one day they’ll take you in as one of their own, but maybe today just isn’t that day. You find your seat, unpack your books, your pencil case, tucking your phone under your hideous plaid skirt. Silly really. Illuminating skirts aren’t exactly the school uniform market’s latest innovation. You’re top of your class. You know you shouldn’t be scrolling through Instagram in a lesson, but everyone else does, and you for sure don’t want to stick out any more than what you already do. You get A’s in nearly every assignment and you compete in nearly every extra-curriculum sport in the school, but you can’t help but fantasise about that Instagram #gymbod. Your parents are immensely proud, and your teachers? You can’t do enough to please them. You love school. Never too shy to raise your hand in class, never too eager to stand in front of the WHOLE of year 11 to deliver a speech about the school’s litter policy, and never too embarrassed to admit to your friends that you’ve not even kissed a boy.

It’s lunchtime. You and your best friends of 12 years gather around the canteen table.They tell you about their exciting weekends. How their heart throb boyfriends distracted them from getting any work done. How they got ridiculously drunk at a family party and how their mum grounded them for coming home at 10:33 – 3 minutes later than expected. And you? You just listen. For the most part, you spend your break and lunch times talking in the hockey team WhatsApp group chat. They’re a laugh. Sometimes you tell the girls about your boring weekend, or even fluff it up slightly by telling them you actually got out of your pyjamas. They would never believe you. You’re well and truly the plain Jane out of the bunch. The new boy in your year asks if the seat next to you is taken. The girls think he’s a nerd but you think he’s quite cute. You say no. The girls sigh as if to say “you’re such a loser”, but you don’t care. You have to pretend you don’t know his name, that you don’t have an unhealthy obsession with checking his Facebook. You know his cat goes by the name of Clive, but you pretend you don’t know that. You know he plays for the local rugby team, but you’re not supposed to know that either. You don’t know that his birthday is the 6th of June, and most importantly, you must NOT show any bitterness towards his girlfriend of 3 years.

Home time at last. You’re loosening your tie as you get closer to the front door, eager to jump straight back into bed. PING. It’s the girls group chat. “House (girl dancing emoji) Sat nite. 8.30. B there or b (square emoji)”. NOOO. You promised mum you’d have a film night with her. Saturday night rolls around. You’ve been plotting all week how you could get away with this one, but she’s a mum. They find out everything. Not this time. You divert from the party situation. It’s now a revision sleepover situation with the girls. You ask to go and of course you’re allowed. School first, partying second. It’s 10pm. You’re having the best time but you assured mum updates on the revision sesh. So, as promised, you load up Instagram stories. On your second Instagram account, obviously. By second, you mean the only Instagram account your mum thinks exists, right? You locate the photo album named “revision”. You browse this until you find the most colourful, most mind-map-ful, most hard working-esque photo you can find. And voila! A little later, in comes a text from mum. “Wonderful stuff. Looks like you’re really working hard. See you in the morning :)” . Little does she know, over on what might as well scream @yourerliar101, several stories and photos were posted of your amazing night with your besties. In the morning it seems the party was a huge success. Tweets and Instagrams raving about the night – “Can’t believe Josh taught every1 to do the (worm emoji) (cry laughing emoji)”. “Had the best nite EVAAAAAA (tongue out emoji)”. “Me and the gals last night!!!!!!! (cocktail emoji) (heart eye emoji) #lovethem”.

Sound familiar? Well, this may not be too dissimilar to a day in the life of your late teenage years. (Millennials, this one is for you!) Through this artificial account, we learn that in just 24 hours, you are likely to perform a variety of different roles. You’re a reliable friend and a caring sibling. You’re also studious, a potential lover and occasionally a liar. But sometimes it’s for the best, right? So, quite literally, how can these personalities become transparent online?

Just like this teenager, the average social media user, whatever you may define this to be, can be traced online. Social media can speak volumes about a person. Not just what they get up to on the weekend, but the finer details. For example, they’re obsession with their house rabbits, how much they can’t stand their boss, and more recently, how they’ve jumped on-board Facebook’s latest bandwagon, “rate my meal”.

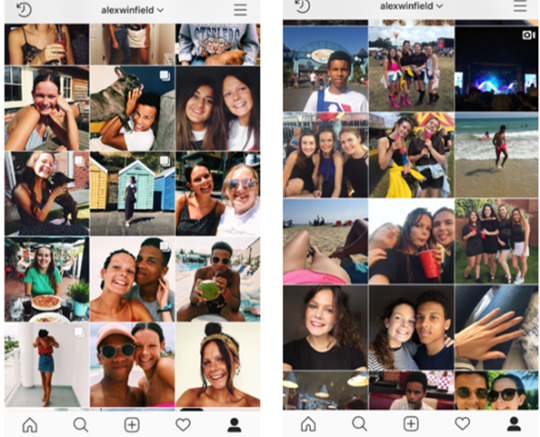

Social media, such as Instagram and Twitter allow me to present the most favourable, or sometimes least favourable, versions of myself. If you were to rewind to old school Alex on Twitter, you would definitely find tweets containing homophones, such as “u”, with my favourite acronym, still to this day, being “lol” – only used sarcastically of course. As well as this, I was a sucker for, and admittedly still am, a cluster of exaggerated punctuation, but mostly “!!!!!!!”. Although Crystal (2008) claims that young users of social media, especially in SMS, will use abbreviations such as “GTGMIW” (Got to go, mum is watching), this wasn’t necessarily the case when I was growing up with social media. Nowadays, it’s all about filtering what you put online. This screening allows you to hide your online activity, for example by disguising your wild Friday night shenanigans by deselecting your mum from viewing your Snapchat story. Or, creating a separate Instagram just for your friends’ entertainment. You can be as embarrassing as you like and you won’t have 800 followers judging you.

Goffman (1974) refers to this online social interaction as “audience segregation”. We ultimately filter aspects of our lives from certain people in order to curate and maintain a multitude of personalities depending on the context we are in. So, for me, this means presenting a sensible, family-friendly Alex on Facebook, an interesting and good-humoured Alex on Twitter, and an exciting, adventurous Alex on Instagram. Let’s take a look…

So, 2017 A-Level Results day. Here, we’ve got a definite exaggerated use of punctuation and excitable capitalisation. Not only this, I clearly thought the use of the extreme smiley emoji X2 wasn’t enough, resulting in going the extra mile with a #. What am I doing here? Looking back on this, this for sure could have been Facebook worthy. This could have bagged me a gushing army of comments from overjoyed family members bursting with pride. But why Twitter? My friends would see this. People I know, but don’t really know, would see this. Those 23 likes - those 23 people thought this was worthy of a tweet and that’s all that mattered. In this moment, I. Was. Clever.

Evidently, over the years, I desired to either be desperately funny or desperately embarrassing. You decide this one.

Would I have found any of these tweets to be bland if I weren’t to use homophones? Or exaggerated punctuation? Or hashtags? Were these attempts for me to moan about how busy my life was? Did I want sympathy or just someone to relate to?

Here’s Instagram Alex. Holidaying in the Dominican Republic, Lanzarote and Greece. Eating Wagamamas at least once a week. Being overly obsessed with a French Bulldog, attending fancy-dress parties and the occasional festival. This is what I choose to share online. Not very exciting, but a fairly accurate representation of me. You can guarantee nearly every other caption incorporates an excessive use of emoticons, sarcasm and most definitely a little too much of this “!!!!!”.

What do these linguistic features allow me to achieve?

If I asked a complete stranger to read my Twitter, browse my Facebook and scroll through my Instagram, they would probably argue that my presence across these social media platforms doesn’t really differ that greatly. You could say that for the most part, I present the most authentic version of myself online. I’m not one to shy away from no-make up selfies, or tell the world about how groggy I feel after waking up from that 3- hour nap, or in fact how much I moan about going to my 20 hours a week part-time kitchen job.

However, for some people, this is not the case. Without audience segregation there would be a context collapse. Employees would start saying “lmao” when their boss asks for a coffee. Students would use inappropriate emoticons to sign of their “sorry I can’t make it to the lecture today, I’m ill” email. Parents would text, or even worse, tag you in their FB status announcing “#DINNERISREADY” instead of actually calling you down for dinner, and we definitely don’t want to live in a world full of parents who hashtag EVERYTHING.

So, what can we learn from this?

For both professional and personal matters, it’s important to present yourself online in a way that is consistent. You don’t want people to think you have 25 different personalities. Keep this for the real-life stuff. No one likes a catfish. After all, if 70% of employers screen candidates’ social media before they consider hiring, it’s important to avoid branding yourself as a fool online. Keep those drunken night out videos OFFLINE and maybe consider deleting those 2012 “Like for a rate <3” cringey Facebook statuses. However, don’t go erasing yourself offline completely in fear that you’ll never get a decent job. After all, 47% of employers argue that having an online presence allows them to learn a bit about who they’re hiring. So, be open, but not TOO open. Be YOU. However, if “you” means writing Facebook statuses about how much you love playing Angry Birds at work, or how you’re easily persuaded to go clubbing on a Monday night, maybe it’s best you don’t share the real you online. Be mindful about the digital footprint trail you’re leaving behind.

References:

Driver, S. (2018, October, 7). Keep It Clean: Social Media Screenings Gain In Popularity. Retrieved from: https://www.businessnewsdaily.com/2377-social-media-hiring.html

Jones, R. H., & Hafner. C. A. (2012). Undersatnding Digital Literacies. London: Routledge.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

There’s a ‘Price’ to pay for meme trolling.

There is no doubt that the social media world are lovers for a good ol’ meme. Need a conversation starter? A witty reply? Or cheering up on a gloomy day? A meme will guarantee you a laugh. However, what constitutes a well-curated, humorous meme? Well, as we all know, humour is subjective. What you and I find funny will differ, of course. But what criteria needs to be met in order for a meme to go viral? What do the creators of memes set out to achieve when sharing them online? Most importantly, is there a line to be crossed? At what point can we agree that a meme no longer has a shared meaning?

I want to look closely at the memes created online targeting Harvey Price, but firstly, let’s get to grips with what we mean by a ‘meme’. Dawkins (2006) describes the practice of ‘memeing’ to involve “participating in the creation or distribution of a powerful, original idea”. He also proposes that a meme is a “unit of cultural transmission”, an idea or collective conscience that a community share. We share this culture like we share genetic characteristics. Like “biological organisms evolve based on the natural selection of genes, cultures evolve based on the natural selection of memes”. Despite what this wishy-washy, too-poetic-to-be-true analysis may suggest, memes speak volumes about the humour and beliefs within society. Remember these?

With the relationship between the image the caption having no etymological meaning, the caption of a meme can be chopped and changed depending on the intention of the creator. Examples which spring to mind are “Cash me Outside” and the compilations of Arthur memes, in which the captions are often quite predictable. Nonetheless, the meaning of a meme is not always required to be clear and linear. Most of the time they are abstract and nonlinear, in fact. Above all, the most important function of a meme is to depict ‘coolness’.

Virality and Memes: the good, the bad but mostly the ugly.

Kim Kardashian, or more specifically her career, is a perfect example of how virality can change a life for the better. All thanks to a leaked sex tape in 2007. You can guarantee that this certainly wasn’t one of her finest, most glamorous moments, but I’m sure she’s never looked back. This scandalous footage landed her a career of fame. And now? Over a decade later we spend our lives Keeping Up With The Kardashians. Most recently, with her half-sister Kylie Jenner competing with an egg to get the most liked photo of all time on Instagram, and her step-father Bruce Jenner’s latest transition in becoming Caitlyn, there is no doubt that this family are familiar with being the centre of media attention. With what seemed to be the world going crazy over an egg, this was an attempt, an extremely successful attempt, to promote mental health, specifically how the pressures of social media can make us ‘crack’. Harmless virality, right? What may have once been perceived to be attacks on the Kardashian family, have ultimately led these stars up a path of wealth and success. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I don’t see roaring headline complaints about them loathing this lavish lifestyle?

But it isn’t always this rosy…

What is the first thing that comes to your head when you think of a troll?

This one?

What about this one?

Or perhaps this one?

Both through her own career as a supermodel and TV presenter, and since the birth of her son in 2002, Katie Price has experienced, first hand, the ugly truth of virality, specifically in the form of trolling. Tweets, memes, death threats, you name it, attacking her son for the colour of his skin as well as his disabilities. Unlike the Kardashians, Harvey is blissfully unaware of the extremes to which he is taunted daily online. But why do we live in a world which allows people to get away with such disgusting behaviour? On a mission, not only to protect Harvey from this online abuse, but anyone who has ever been subject to trolling, in 2017, she started a petition. This eventually received over 200,000 signatures in a bid to make online trolling illegal. Despite her best efforts at exposing these trolls herself, she discovered there to be little, if any, law enforcement in place to protect victims such as Harvey. Being what Goldhaber (1997) describes to be a “star”, fortunately, she was equipped with the tools to attract mass media attention about the issue of online trolling, to which she appeared on many day time TV programmes informing people about ‘Harvey’s Law’.

In spite of her good intentions, it was no shock that trolls not only continued to fire hate filled tweets about Harvey, but curate memes mocking things he has said on TV appearances, as well as taking content Katie had uploaded to her own social media of Harvey as inspiration.

Any mum would agree that just because she’s in the public eye, it should not mean that she should be deterred from posting photos of her children on social media to protect them from being targeted by trolls.

A clip which many may be familiar with is their appearance on Loose Women, in which he swears on live TV. Although trolls immediately took to photoshop to mock this display of innocence, many could argue that this is part of the viscous cycle of attention economy (Goldhaber, 1997). In order for trolls to give Harvey attention, they need a source to retrieve it from. Contrary to her pledge to protect Harvey from the doom and gloom of social media that we all know and love, she was recently slammed for ‘baiting trolls’ (The Sun, 2019) by setting Harvey up with his own Instagram account. Is this ultimately an invitation for trolls to attack him? Does it provide trolls with the ‘new’ and ‘original’ content they so desperately desire? What do we think, is she now responsible for the trolling Harvey will now be exposed to online?

youtube

A more recent adaptation of memes, known as GiFs, has also been a platform explored by trolls in order to attack Harvey further. During my research into this topic, from simply typing into my search engine “Harvey Price”, this result appeared…

As if memes weren’t exhilarating enough to fulfil the trolls in their cyber-attacks, GiFs of Harvey can now be generated through this site, ultimately allowing people to express themselves in online conversation through indirectly mocking Harvey. But to them it’s nothing serious. Just a passing comment. What angers me the most about this GiF generator is the use of the term “popular”, suggesting that people visiting this site will have access to nothing but the best GiFs - what the trolls would label to be most successful in terms of their virality. First and full most, who is spending their time designing these websites, and secondly, are they proud? Are they THAT disconnected from their emotions that they don’t view this young man as a human being?

But do these memes live up to the definition of ‘memeing’ proposed by Dawkins (2006)?

Are they powerful?

Definitely not.

But perhaps in one way? They’re powerful for delivering the message that no matter what your race, your sexual orientation, your disabilities or your religion, there will always be people in the world who disagree or are opposed to it. Sure, trolls can hide behind their twitter username, but can they hide from their own insecurities? This is important to consider. What is the need for them to create this content? For how long is it funny? A day? A couple of hours?

Are they original?

Most certainly not. If anything, they lack originality. Well, put it this way, I can’t hear anyone applauding these creators for their outstanding pieces of work…

Is it cool?

You must be joking?

The creators of this content might have themselves fooled that they are some- what inspirational to the rest of the nation, or that they’re admired by their fellow meme-ers for their hardcore memeing. But the rest of the nation? The decent human beings of the nation? Disgraceful. Unintelligent. Bullies. A valuable point to be made here is that creators of memes believe they’re in a superior position to those they are ‘memeing’ about, hence why when these memes are shared and distributed online, they appear ‘funny’ to those who perceive Harvey as inferior to them.

And this is why we can’t have nice things…

Phillips (2015) argues that essentially, trolls “are the reason we can’t have nice things online”. He suggests that the online space is meant to be a community where people can feel safe in sharing their thoughts; through tweeting, or sharing snapshots of their life via Instagram. It appears that sadly, this is no longer the case. Trolls are “born and embedded” within dominant institutions. As a result, the saddest, and most frustrating thing of all about meme trolling, is that as long as trolls have the community to support them, and until social media platforms build stronger, much more stable networks which block out these trolls, there will be no end to trolling. This “unapologetically racist humour and legitimate corporate punditry” will only seize to exist online if the threat of the law was to stand between the troll and the ‘send’ button. Why, in those “golden years” between 2008-2011 in which the trolling subculture became “crystalized”, did establishers of these social networks make a stand for this unwanted behaviour? Why is a mother, regardless of whether she’s famous or simply just the mum next door, forced to make a pledge for this internet craze to be wiped from our screens?

How can we make a difference?

It is important to not turn a blind eye to this kind of behaviour online. Although it may not directly affect you, there will always be someone else is in the firing line. Avoid retweeting, sharing and even posting content online which may later come back to bite you. As someone who has been a present, and an active user of social media since my early teens, during this time, I was extremely naïve to the content online. I’m sure there have been posts which I would look back on now and think how my online presence has changed. My humour has changed. What I like and post about has definitely changed, but most of all, social media as a 20-year-old seems a much scarier place to be than when I was 13. Do you agree?

References:

Phillips, W. (2015). This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship Between Online Trolling and Mainstream Culture. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Dawkins, R. (2006). The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gibb, J. (2019, January 28). Katie Price accused of ‘baiting’ trolls. Retrieved from: https://www.thesun.co.uk/tvandshowbiz/8300554/katie-price-accused-of-baiting-trolls-by-giving-son-harvey-his-own-instagram-account-and-failing-to-protect-him/

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Plato on Zoella and the McCanns.

With Plato’s philosophy regarding knowledge and wisdom to hold greater significance over writing, what would he say about the modern-day interpretations which express such knowledge and wisdom through the medium of reading and writing online?

Let’s start with Zoella. If “wise men speak because they have something to say; fools because they have to say something” (Plato), what exactly is her approach to writing? What can we learn from her blog? How is the ‘blogsphere’ world becoming so evidently corrupted and fuelled by consumerism?

Well, just a little under a decade ago, Zoe Sugg, also known as Zoella, set up a blog orientated around fashion, beauty and lifestyle. Since then, she has published a sequel of 3 fiction novels, with her most recent publication “Cordially Invited”, offering advice on how to host the perfect party. Alongside being an avid book worm, and having a passion for fashion, she documents her day to day life though the notion of video blogging, better known as ‘vlogging’. Although Plato would commend her eagerness to write, he would argue to what extent does her content focus on “moving from opinion through to knowledge” (Sherman, 2013).

In recent years, Zoella has openly admitted to have lost touch with her blog, often feeling uninspired to write, resulting in more visual documentation of her life via her YouTube channel and Instagram. Why? I mean, the most obvious guess, especially from a millennial’s perspective, is that it requires much less effort to whip out a camera and film a few hours-worth of footage than to sit down and write (or more typically, type). What she may consider to be a ‘subtle’ approach, her blog (AND Instagram) is undoubtedly a gateway for brands and companies to promote their services and products, to which Zoe declares to only work with brands she feels passionate about, or believes her viewers will benefit from. In 2017, Zoe honestly reviewed (referred to as an #Ad) some beauty products gifted to her by the well-known beauty brand ‘Benefit Cosmetics’.

Through incorporating a hyper-textual structure of hyperlinks (Baehr, 2007) within this blog post, she was able to send her readers in the right direction to browse, but most importantly purchase these products. You might be thinking “so what, that’s her job!”, but here, Zoella is cashing in on her ability to persuade her audience that buying the specified brow pencil will create the “professionally styled” brows we apparently all desire. Is this educational? No. Does she allow her readers to access knowledge which only she once possessed? Not really. So, to what purpose does this discourse serve? Although many of her fans would disregard this post as being click-bait, arguing that we all have to make a living some way or another, is her blog essentially just a platform for her to express her entitlement in the up and coming influencer world? Does it provide her with opportunities to show off the excessive amounts of products she is gifted and the amazing holidays her fans can only dream of? If her writing does not share wisdom nor knowledge, would Plato consider this to represent a voice in society who speaks because they feel obliged to stay something (for example, in order to be paid), not because they have something important to say?

Alternatively, if “wise men speak because they have something to say; fools because they have to say something”, how would Plato’s philosophy take prominence in the evaluation of the concept of blogs such as NetMums?

With NetMums being considered as the largest parenting website offering information and advice in the form of blog-style chat rooms, competitions and recipes, how does this style of read-write web illustrate the collective intelligence of wisdom and knowledge that Plato so desperately seeks out over writing? Well, NetMums is free for anyone to access, most obviously parents, where pending questions about parenthood can be shared. Worried about what to expect during labour? Not sure how to approach talking to your child about mental health? What are the symptoms of pregnancy? NetMums has got you covered! All in all, a place for parents to learn about the many wonders of parenthood. Reassurance for single parents. Advice for new parents. A warm hug for grieving parents. THE portal of wisdom and knowledge that can be attained only through experience.

“For by telling them many things without teaching them will make them seem to know much while for the most part they know nothing, and as men filled, not with wisdom but with the conceit of wisdom” (Plato).

Unlike Zoella’s blog, NetMums offers a platform which has the ability to teach its readers, instead of simply ‘telling’. Zoella ‘tells’ us about her travels to Mykonos, ‘tells’ us about her new beauty launch, and ‘tells’ us how to throw the most incredible picnic party. But what are we taking away from these reads? Plato defines these readers to be the product of conceit of wisdom. Are we fuelling this egotism?

How can we compare this to traditional modes of writing?

Alternatively, if “wise men speak because they have something to say; fools because they have to say something”, how would Plato’s philosophy examine the motivations behind the publications of autobiographies? Such as the likes of Michelle Obama. How does she use her platform to inspire others?

In her biography ‘Becoming’, published in 2018, she shares her triumphs as well as disappointments amidst her journey of becoming the first African-American First Lady of the United States. She used this platform to not only inspire but to educate her readers about the importance of living an active and healthy lifestyle, but to take stand against the many wrongs in the world. With women’s educational rights, both in the U.S and all around the world, being a cause close to her heart. Whilst being the centre of an unavoidable media glare, she has undoubtedly shaped a unique sized hole for those wishing to follow in her footsteps. With her story defying all expectations, she is truly an empowering force to be reckoned with. But what would Plato say? Well, there is certified wisdom – she oozes intelligence, being once a lawyer, but not only within her professional network, but her skilfulness in utilising her “author’s intelligence” (Sherman, 2013) in order to empower wider communities, instigating a change in humanity. But what about knowledge? If power means knowledge (and knowledge means power), and we all know this is not something she once lacked, this must surely tick all of Plato’s boxes?

Similarly, but on a more controversial level, if “wise men speak because they have something to say: fools because they have to say something”, how could Plato’s philosophy be applied to Kate McCann’s non-fiction publication, following the disappearance of her daughter Madeleine?

A statement provided by Kate outlines the reason for this publication being to “give an account of the truth”. As many celebrity biographies set out to achieve, the element of story-telling and use of emotive language serves the purpose of closing the gap between the author and the reader. However, 10 years down the line, we are still none-the-wiser about Madeleine’s disappearance. What is the purpose of this book? How does it enable those involved in the investigation in discovering the truth? Is it a decoy? To distract the real truth from being uncovered perhaps? Or, did they see this as an opportunity to profit from this tragedy?

Plato’s response on the other hand? No wisdom. No knowledge. Merely an example of writing which has be publicised by an author who needed to say something. Whether that was due to the pressure of being in the public eye, or simply to keep the memory of Madeleine alive, it is not clear. Cynically, Plato’s philosophy would define this as a text which does not contribute a wealth of substance to the already existing views of the world. Would Plato consider Kate McCann’s publication to be of higher value if it were to explicitly console other parents who have experienced the same heart break of losing a child? Or, more practically, teach other parents the importance of keeping their children safe abroad?

So, what relationship can we identify between Plato’s philosophy and reading and writing online?

You might be thinking that this philosophical view comes across as a bit hasty or blunt? However, philosophers like Plato have extreme views and opinions on experiences which occur within the world in which they use to argue about different matters. This short YouTube video may give you a better understanding of Plato’s philosophical assessment of reading and writing, specifically the linguistic terminology used by philosophers to define terms such as knowledge and truth value.

youtube

9 times out of 10 we take something at face value, but does that mean we are gullible? No, not necessarily, but it does mean our knowledge and experiences of the world are not always reliable. We believe the sky is blue because we experience this through first person observation. So, why are we under this illusion that just because someone is a published author or blog writer that their knowledge is in fact reliable? Zoella is some-what an expert in the realm of make-up, but her excitable promotions about how wonderful these products are can be perceived by Plato to be nothing but testimonies. We take this knowledge and shape it to suit our beliefs. If you want that mascara to be as amazing as she says it will be, you will create this impression for yourself that it truly is the best make up product on the shelves in Boots.

And the McCanns? Well, with there being no doubt that the nature of some events which occur in this world can be so evidently cruel, should we take what is said about the disappearance of Madeleine to express a propositional attitude of disbelief or belief? Do parents who read and write Netmums essentially give and take advice on parenting which are fundamental beliefs of those who have gained knowledge from elsewhere? For example, their parents, parenting masterclasses, books or google?

So then, if knowledge can be defined as “justified true belief”, what can we learn about reading and writing online?

All in all, reading and writing is a medium for people to use their free will in order to express their opinions and experiences. However, for as long as the online world exists, reading and writing online will continue to create a vulnerability for people to construct their own beliefs based on what could be argued to be a bed of lies. The notion of googling our symptoms to find out if we are dying is perhaps one of the most accurate examples of how reading and writing online does not provide people with wisdom nor knowledge. So, always take what you read online with a pinch of salt. Unless you have first-hand knowledge, then knock yourself out.

Although Plato argues that we should not rely on which is written to sustain these valuable human qualities, but instead exercise the memory, new media platforms as well as traditional methods of writing such as publications, cannot exist independently from the modern-day world. With Plato claiming that writing seizes to offer “no true wisdom” but only its “semblance”, the texts examined here undoubtedly showcase how writing merely strengthens the wisdom and knowledge people can possess through sharing this with others. What do you think? Is Plato’s philosophy outdated in today’s society or does it provide a valuable contribution to our understanding of reading and writing online?

References:

Jones, R. H., & Hafner, C. A. (2012). Understanding Digital Literacies. London: Routledge.

Sherman, D. (2013). Soul, World and Idea: An interpretation of Plato’s “Republic” and “Phaedo”. Plymouth: Lexington books.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

They’re listening.

It is not a recent phenomenon that our every move is being traced. You can’t do many things or go many places these days without being watched. Via CCTV in public spaces or home surveillance systems emplaced within our local communities, someone is watching you. Our phones also enable us to track our location, as well as the contacts we choose to follow, through the ‘Find Friends’ app on iPhones, as well as Snapchat’s adapted version of ‘SnapMaps’. We have become OBSESSED with keeping tabs on people. As if following them on social media wasn’t enough, parents can now keep tabs on their children, couples can keep tabs on their partners and the most bizarre thing of all, we can’t function without this. Is this an unhealthy obsession? Are these instalments meant to keep us safe? Or are they too exposing?

With the algorithms of Instagram and Facebook tailoring our feeds to suit our every need, we often don’t question where this information comes from. Why on the daily am I exposed to ad pop ups trying to sell me short mini breaks to Edinburgh or student discounted tickets for the cinema? Despite the social filters which reassure me that my information is being stored and analysed to curate a social media that represents my best interests, why is it that I am so engulfed in paranoia that tells me I’m always being listened to? Why is it when I look around in my lectures that nearly every other student has covered their web cam with blue-tack or a torn up post-it-note? Understandably, the student budget may not stretch as far as purchasing anti-spy software, but what is it that we are so afraid of? It used to be the older generations (such as the likes of my mum) that feared the exposure of their personal information online, but now it seems that increasingly more young social media users are taking a leaf out of their book…

Advancements in technology such as the Amazon Alexa and Siri exist to make our lives that little simpler (or arguably lazier). “Alexa, play my revision playlist”, “Siri, what’s the weather like today”, “Alexa, turn the TV on”. Without the lift of a finger. So why on Earth are we complaining? Despite Facebook insisting that it doesn’t eavesdrop on conversations in order to target users for adverts or content, why have the designers of the new Huawei P20 phone incorporated a pop-up notification that warns their users not to cover the top of the screen? Are the conspiracy theories true? Is there really a burning desire for the government to listen and observe our every move?

My main concern surrounding this Hunger Games-like concept is that I often receive ad pop ups for content which I haven’t physically engaged with via Google searches or conversations with people through messenger apps. Although I often catch myself making jokes like “oh Theresa May must be listening” or “don’t google that, you’ll look like a weirdo”, this must surely suggest that I am consciously aware of what I interact with, what I google and what I discuss with my friends. Might using key words trigger audio recognition of information that could be used against me? Extreme but rational.

youtube

After watching this short trailer of the film ‘Searching’, it could be interesting to examine how the data processed by external agencies or “collective intelligence” could be used to trace our identity. For example, to gain an insight into my whereabouts in a time of crisis, similar to that displayed in this film. Alternatively, it is worth considering how it could be just as easy to create a false identity based on my google searches, online conversations and social media interactions. Could I create a filter bubble which is so different to my real interests that I can become unrecognisable online?

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

How can Instagram act as a mediator between the online world and ‘real-life’ relationships?

Instagram is a blessing in many ways. It is a communication medium which allows you to form relationships and interact instantly with people online, as well as be creative with content. However, affordances like these can encourage people to view Instagram through rose tinted glasses, with it being so easy to get caught up in the falsities of Instagram – checking who is following you, who is liking your photos and what your friends are up to. But how do we know what is real life and what is curated for those who follow you online? Of all the social media apps I interact with, I spend the majority of my time on Instagram. I AM A SERIAL SCROLLER.

The most notable constraint when it comes to my usage of Instagram is how increasingly lazy I become with communicating. I often find myself going weeks, sometimes even months without contacting long distance friends, for example school friends back home whilst I’m at university. You can become so comfortable with liking or following content posted by your friends or family that this can replace the effort made in your real life relationships.

Through conducting a small online survey questioning “why does it hurt to be unfollowed?”, shared amongst friends and my followers on Instagram, 28% of respondents agreed that Instagram can ruin real life relationships. This is due to the immense “pressure to live and look a certain way”, as well as Instagram users “thinking other people look better or happier”. As a result, it is no surprise that Instagram has the power to distort people’s perceptions of body image.

Instagram can trap you within this illusive bubble, allowing you to convince yourself that you really know someone, when in fact they are just a stranger, with one respondent commenting that Instagram followers can presume “to know all your business”. You believe that you are in tune with people through a screen, when in fact this couldn’t be further from the truth. Instagram is a double-edged sword. Although only 14% of respondents honestly agreed to never post authentic representations of their life, it is common for people to feel such pressures to document a perfect lifestyle online, and in return, this is exactly what all your followers are doing. Is it a trend? A competition? Are we all competing for the most followers? The most likes? What actually is it that we want to gain from Instagram? I spend HOURS scrolling through the Instagram explore page admiring all the aesthetically pleasing accounts of girls who gym, couples who travel, and friends who lunch, but why? Surely everyone can see straight through these filters. Surely everyone knows how set up these posts are? Are we all striving for this unattainable perfect life? Cynically, yes. Without generalising, 42% of respondents agreed that there is an immense pressure to regularly document aspects of their life on Instagram, even if they don’t feel like what they’re posting is necessarily exciting.

I remember the days when I was 13, when Instagram first came about. It wasn’t about likes or followers but about using the wackiest of filters (what even was an editing app in those days?) and reaching 11 likes. This was the peak of popularity. You’d made it in the Instagram world. Instagram WORTHY. Now? You have to get a least 100 likes to feel like a photo is worthy of keeping. Just over 30% of respondents agreed that they usually feel like a post isn’t good enough if it doesn’t exceed a certain number of likes. No need to worry though, you can almost guarantee that you’ll have the support of your friends and family. 66% of respondents agreed they would like your photo even if they didn’t necessarily ‘like’ it. Disheartening, right?

So, the question is, what does it mean to be ‘unfollowed’? 21% of respondents agreed they probably would unfollow someone who didn’t interact with their Instagram, through liking, viewing or commenting on their posts. Also referred to as ‘ghost followers’. However, 53% of people said its not so important to have lots of followers, with only 3% stating that it is. 35% of respondents agreed that there is a strong relationship between the number of followers you have and popularity, concluding that perhaps not everyone has this desire to be popular. However, nowadays it is not unreasonable to assume that an account with 10,000+ followers must be some kind of influencer, being paid to post photos of their #OOTD or their summer holiday of a lifetime to the Maldives.

Ultimately, there is a fine line between what it means to have social MEDIA and a social LIFE. Instagram is a mediator between what is real and what is notional for the purpose of popularity. It provides a platform for people to create an identity which differs from the real version of themselves. The most important question that this phenomenon provokes is whether Instagram promotes positive messages for its users. With there being a very close trend between those who agree that Instagram is positive (32%), neutral (28%) and negative (25%), it is fair to say that Instagram is a way for people to be accepted within society and those outside this circle are to be defined as ‘anit-social’. Has the ‘instantness’ of Instagram been extracted in recent years? Does this platform of social media convey much deeper meanings than just simply posting photos?

6 notes

·

View notes