Text

Assignment 4 - Africa beyond the west: visuality, politics, identity

This essay attempts to contextualise advertising in context of modernity during the 19th and 20th centuries in Europe and Africa. For purposes of framing, modernism and colonialism will be discussed. How these concepts linked to African art, imagery and advertising will also be considered. Finally, specific examples of advertising which entrenched and dislodged the colonialist agenda in Britain and Ghana respectively, will be compared.

Modernity was conceived in 17th century Europe and describes the revolutionary concepts and technological advances which changed the structure of society (Van Robbroeck 2006: 29). A prominent theory was that European exploration and discovery was imperative to creating a “modern Western self-consciousness” (Van Robbroeck 2006: 31). Begam and Moses argue that modernism and colonialism are inextricably linked since modernism calls for rethinking issues which, at that time, included territorial expansion (2007: 3). With Modernism came the need to scientifically classify and explore the unfamiliar; the ‘mysterious’ continent of Africa was “the right kind of challenge” (Khapoya 2010: 101). Scientific exploration as well as imperialism and egotism all led to Europe imposing colonial rule upon Africa (Khapoya 2010: 104).

In Edward Said’s Orientalism (1987), he explains that the West divided the social framework of the world into the mutually dependent ‘us and them’ (Sankar and Suresh Kumar 2016: 210). Europe established itself as progressive and scientific while identifying Africa as under developed (Van Robbroeck 2006: 50). By the nineteenth century, Europe had formed a limited and biased image of Africa which benefited the West’s agenda (Landau 2002: 2). Western Europe used ‘science’ to justify racism and prejudice; portraying Africa as dark, wild and mystical (Landau 2002: 4). The West’s alienation of Africa as the Other became a justification to conquer the continent.

Ania Loomba defines colonialism as “the conquest and control of other people’s land and goods” (2005: 8). Although colonialism occurred all over the world and throughout human history, the native people of the colonised country were always violently conquered (Loomba 2005: 7). Specifically in Europe and Africa, the West gathered information about Africa and used their understanding of science to draw racist conclusions that African people were inferior (Landau 2002: 4). The aim of colonisers was to dominate the colonised by stripping them of their identities since they were regarded as small and insignificant (Sankar and Suresh Kumar 2016: 210). Africans were dehumanised and had their authority taken from them (Sankar and Suresh Kumar 2016: 211). This dehumanisation occurred in various ways, including violently instilling a mental and physical culture of obedience among native people (Sankar and Suresh Kumar 2016: 211). Europeans discouraged African cultural practices and languages, and even changed their names to Christian ones (Khapoya 2010: 102). The African people were given a Western education in an attempt to ‘civilise’ them, and although this intellectually benefited young Africans, Khapoya (who attended a colonial school), explains how it ultimately removed them from their cultural traditions (2010: 103). The practice of disrespecting culture and rituals also occurred with the appropriation of African art.

European artists’ first experience of African art occurred when colonisers brought pieces to western museums and galleries (Crawshay-Hall 2013: 19). Objects, including masks and sculptures were initially regarded as artefacts which the West used to form an understanding of African cultures (Landau 2002: 7). Crawshay-Hall argues that the exposure of Western artists to African cultural art permanently changed the modern-art landscape (2013: 19). Van Robbroeck links the concept of curation and authorship by explaining how curators make connections through the display of work which gives them control of the narrative and the ability to change the works’ meaning (2006: 9). Western artists directly copied African art styles and subject matter, and the curation of African museums encompassed the mindset of colonialists in terms of appropriation and removal of agency (Landau 2002: 7).

The concept of agency is defined as the ‘socially determined’ ability to actively effect change (Barker 2012: 496). Colonisation relied on the false idea of African culture being unchanging (Crawshay-Hall 2013: 3). Europeans claimed that Africans were not fully conscious subjects because they were not aware of their existence as humans (Van Robbroeck 2006: 64). This colonial mindset aligned with the idea of Africa being a place full of unthinking barbarians with a lack of civilised culture (Van Robbroeck 2006: 64).

Colonisers created a homogenous image of Africa which showed all African people as dangerous (Sankar and Suresh Kumar 2016: 212). Europeans described their travels in Africa as if they were “traveling from civilised lands to uncivilised ones, from humanity to savagery, from logic and knowledge to ignorance, and from peace to war.” (Sankar and Suresh Kumar 2016: 213). Africa’s existence in Europe was mainly image based and that African people had no say in the creation or distribution of these images (Landau 2002: 5). Africa was portrayed in an entirely one-dimensional way through visuals of weaponry, wild animals, landscapes and witch-doctors (Landau 2002: 5). This inaccurate portrayal of Africa manifested itself in visual media such as advertising.

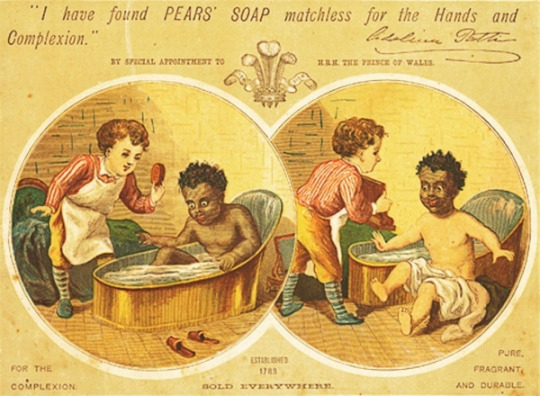

Cocks acknowledges that advertising in Britain in the 19th century was a product of modernity and the Western self-consciousness (2004: 6). The field began to be used to navigate the opportunities and problems of the new modern world which Britons lived in and advertising became a tool to spread the white colonial agenda (Cocks 2004: 6). Imagery which portrayed black people as savages, thus entrenching racism, appeared on commodity items such as biscuit tins, alcohol bottles and soapboxes (Barker 2012: 272). Soap, in particular, which carried connotations of cleansing and purifying, became a metaphor for colonisation which aimed to domesticate and clean Africans of their barbaric ways (Barker 2012: 272).

Figure 1 is an advert for Pears’ Soap which was printed in the 1890’s (Stern 2008: 207). The blatantly racist advertisement depicts Africa as a black child who is being washed clean of his ‘blackness’ by the whites (Stern 2008: 206). The depiction of a black child goes together with the colonial concept of Africans as undeveloped and immature (Van Robbroeck 2006: 65). The child is first fearful of the water and then ecstatic with his now white body which supports the aim of colonialists to transform and civilise African society, but misrepresents the general response to colonialism again removing African authority (Khapoya 2010: 107). Repeated in figure 1 is the effectiveness of Pears’s soap on the “complexion”. The specific use of the word “complexion” and its repetition further equates colour to culture and emphasises the idea that black culture is undesirable and should be ‘cleaned off’ as it is is literally dirty (Stern 2008: 208). The black child is stripped of identity and is naked which communicates vulnerability. This mirrors how the West viewed Africa, as a commodity which they could conquer.

In 1821, Britain colonised the Gold Coast in West Africa and exploited them for their various natural resources such as gold, diamonds and pepper (Miller and Vandome 2009: 1). The West used their control of African colonies to farm specific commodities like coffee, tea and cotton (Khapoya 2010: 131). Ghana was especially well suited for growing coffee and cocoa and was thus exploited through the cash crop system which resulted in massive famine across the country (Khapoya 2010: 131). After the Second World War however, colonised countries around the world were beginning to gain independence and it was in 1957 that Ghana won its independence from Britain (Miller and Vandome 2009: 1).

Postcolonial visuality in Africa had appeared to have progressed from ‘traditional’ to ‘modern’ (Unknown 2018: Online). However there is the argument that tradition, like modernity, is also “an active process of handing on” which goes against the view that the colonists had of a static, backward Africa (Unknown 2018: Online). Africa’s newfound modernity manifested itself in visual media like advertising.

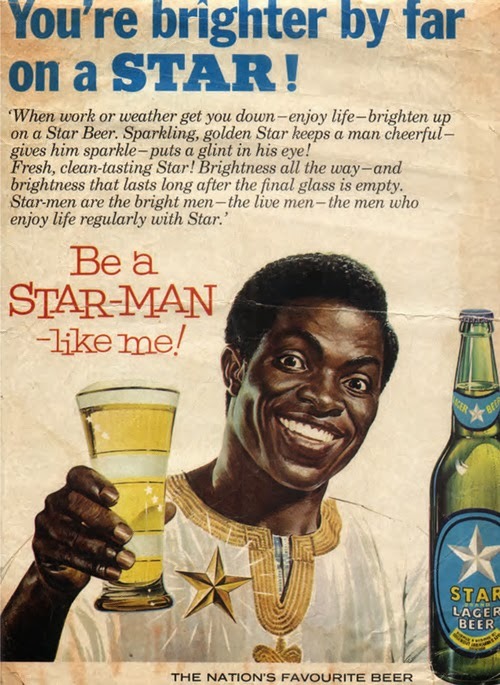

Figure 2 is an example of an African advert which shows that Africa, by example Ghana, reclaimed its modernity after gaining independence. Van Robbroeck writes that modern Africa was no longer considered static and this is evident in the advert through the choice of energetic phrases like “live men” and “gives him sparkle” (2006: 91). The advert shows a contemporary setting which is far from the rural aesthetic which encompassed Africa’s identity during colonial times (Van Robbroeck 2006: 92). However, African modernity also resulted in cultural hybridity and figure 2 shows the subject in cultural dress thus visually combining the modern and traditional (Van Robbroeck 2006: 92). The advert does not entrench the alienating ‘us and them’ narrative which allows for “transnational understanding” (Van Robbroeck 2006: 92). The African man dominates the advert, looking straight at the viewer while smiling, which communicates confidence and pride as opposed to figure 1 where the black child is portrayed as vulnerable in its nakedness. The black man is also clean and words like “fresh” and “clean-tasting” are used in the advert. This contrasts figure 1 where Africans were portrayed as dirty and uncivilised. Figure 2 is unframed, unlike figure 1 which was enclosed in a kind of bubble. The framing of the adverts alludes to Britains control and then to Ghana’s autonomy. The text at the bottom of the advert “The nations favourite beer” portrays Ghana as an independent country with the self-determination to make choices.

To conclude, advertising in Britain was a tool which was used to promote white colonialism and promote racist ideologies. Once Africa gained its independence, countries like Ghana clearly communicated an African modernity through print advertisements which portrayed Africa as autonomous and with agency over its identity.

(1593 words)

0 notes

Photo

Fig 2. Star Beer. ca 1970. Street art advertisement in Ghana. (Osei Kwadwo 2014: Online).

0 notes

Text

Assignment 3 - Modernity: Inventions and Expressions

This essay attempts to place the artistic field of photography within the greater context of nineteenth century modernism. Various advances within photography as an artistic medium will be discussed in terms of technology, art, science, motion, landscapes and cities. These developments are all based on the principles of the modernist era within which they occurred.

Modernism is described by Van Robbroeck as the philosophical and political development of ideals from medieval to modern times, beginning in the 17th century (2006: 29). Various developments in the scientific field led to the questioning of the superstitious practices and feudal structures in which the medieval world was rooted (Van Robbroeck 2006: 30). According to Giddens, modernity signalled an emphasis on the rational and scientific with all systems and concepts being open to revision and change (1991: 214). The focus on the rational led to urbanisation which artists responded to by using the medium of photography (Stokoe 2014: 18). As Irvins said, ‘The nineteenth century began by believing that what was reasonable was true, and it would end up believing that what it saw a photograph of was true’ (Verdon 2016: 68).

When cameras were first invented, they were initially only used by the wealthy and high class since they were expensive and difficult to operate (Sontag 1977: 7). The Industrial Revolution, which took place between the 1700’s and 1800’s, marked the shift from an agricultural society to one which made use of machinery and technology (Roberts s.a.: Online). The way camera technology so quickly developed mirrors the swift changes in philosophy during the era of modernism (Clarke 1997: 19). The industrial revolution led to improvements and advances in the camera; this ultimately resulted in the democratisation of human experiences through the act of photographing them (Sontag 1977: 7). The eventual accessibility of the camera also blurred the line between the upper and lower classes, which aligns with the sense of equality that modernism advocated (Clarke 1997: 53). The photograph became the ‘ultimate democratic art form’ by giving all people the opportunity to record their lives (Clarke 1997: 19). This democratisation of photography found ground in portraiture in that it allowed ordinary people to take pictures and to have their pictures taken (Clarke 1997: 104). Portraits captured the individuality of the subject and the camera treated all as equal (Clarke 1997: 107). The act of photographers choosing people from all social classes as subject matter further emphasised the values of autonomy which modernism advocated (Clarke 1997: 107).

Towards the beginning of the modernist era, photographs were viewed in relation to how one would view a painting, and so photographers used similar subject matter like portraits and still-life’s (Clarke 1997: 42). Art-photography was developed through the same principles and values which paintings were conceived (Clarke 1997: 42). This is evident in figure 1; a photograph which shares many of the formal elements of a still-life painting (artnet s.a.: Online). However, unlike paintings, what the photographs depicted was ‘real’, since they were capturing things that were palpable, and photographers were intrigued by the idea of the camera being an actively curious part of the process (Clarke 1997: 45). The act of photographing as opposed to painting or drawing something aligns with the modernist shift towards rational and scientific thought (Clarke 1997: 45).

Photography had an immense effect on the artist (Roberts s.a.: Online). Photographs were regarded as a new, academic art which could capture things exactly as they were (Clarke 1997: 43). This threatened painters since photographs could do their jobs faster and, in some cases, better (Roberts s.a.: Online). Industrialisation also aided artists by allowing them to travel via railroad and thus source new subject matter (Roberts s.a.: Online). Photography also enabled painters to capture fleeting moments which would otherwise be impossible to reproduce (Roberts s.a.: Online). As said by Hoppé of photography, ’Here is a blending of art and science, or art and mechanism, that can meet the subject on its own ground’ (Stokoe 2014: 18).

In the modernist period, there was an attempt to explain reality through science and photography was able to observe in a simple, objective manner (Van Robbroeck 2006: 35). Photography is, by definition, ‘light-writing’ because of its dependence on light and energy (Clarke 1997: 11). This name is fitting due to photography’s purpose of documenting nature and scientific processes (Clarke 1997: 55). The scientific revolution during the 1800’s placed focus on proof and documentation to establish a system of order and knowledge throughout the world (Van Robbroeck 2006: 35). Sontag explains how industrialisation allowed for photography to become valued by society as a medium of evidence (Sontag 1977: 8). ‘Photography is, broadly, the first mechanical inscription technique that claims to objectively represent reality.’ (Verdon 2016: 69). This idea of everyday realities being considered art was a revolutionary step in the modernist era (Meecham & Sheldon 2005: 24). The concept of capturing actuality is clearly shown in figure 2 which is a photograph from the book How The Other Half Lives by Jacob Riis (International Centre of Photographer: Jacob Riis s.a.: Online). His photographs depict the ghettos of New York and draw focus to the horrific conditions the underprivileged had to live in (Clarke 1997: 147). Because photographs could, to a certain extent, mimic reality, they were used to portray a realistic record of the world (Sontag 1977: 22). This shows the greater frame of mind at the time of wanting to control scenarios by preserving them (Clarke 1997: 45).

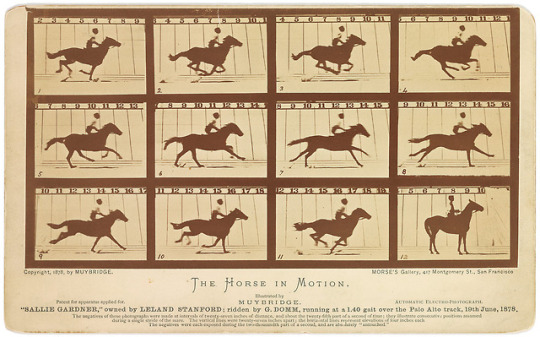

With the technological advances in photography came the creation of stereoscopic imagery (Verdon 2016: 72). This is when multiple photographs are put together to create the illusion of a moving image (Verdon 2016: 72). Eadweard Muybridge used stereoscopes to gain insight into the movement of animals (Atkins 2017: 511). The overall aim of recording this movement was to be able to ‘improve understanding’ and ‘settle debates’ both of which align with rational and scientific thought (Atkins 2017: 511). Figure 3 shows an example of a stereoscope by Muybridge (Time: 100 Photos s.a.: Online). The purpose of this study was to find out whether all of a horse’s legs are suspended in mid air while it runs (Time: 100 Photos s.a.: Online). This use of the camera was groundbreaking in that it would shortly lead to another revolutionary invention, namely, motion pictures (Time: 100 Photos s.a.: Online). But overall, stereoscopes show that people were interested in investigating natural processes; a key principle of the modernist era (Van Robbroeck 2006: 32).

Core principles of modernism included the domination of the natural world (Van Robbroeck 2006: 32). Photography became a tool during this time of discovery and just as settlers were conquering new lands, photographs were visually capturing and recording these scenes in the form of landscape photography (Clarke 1997: 55). The technological advances that came from the industrial revolution included new modes of transport which gave photographers the opportunity to shoot new territories (Clarke 1997: 55).

Industrialisation signalled the move from farm to city life. Cities were thus seen as new and modern (Clarke 1997: 80). The growth of urban areas provoked a photographic response which captured the complex nature of city life (Clarke 1997: 75). Photographers followed the modernist way of seeking visual opportunities by using cities as subject matter (Stokoe 2014: 3). Since cities were constantly changing with new developments emerging everyday, photography allowed for cities to be documented for future generations to see which aligns with the mindset of documentation during the nineteenth century (Sontag 1977: 16).

The field of photography was heavily influenced by the shift in thinking which occurred in Europe between the 17th and 19th centuries. This essay considers the technological advancements and general values attributed to modernism which led to various advances in photography.

(1305 words)

0 notes

Photo

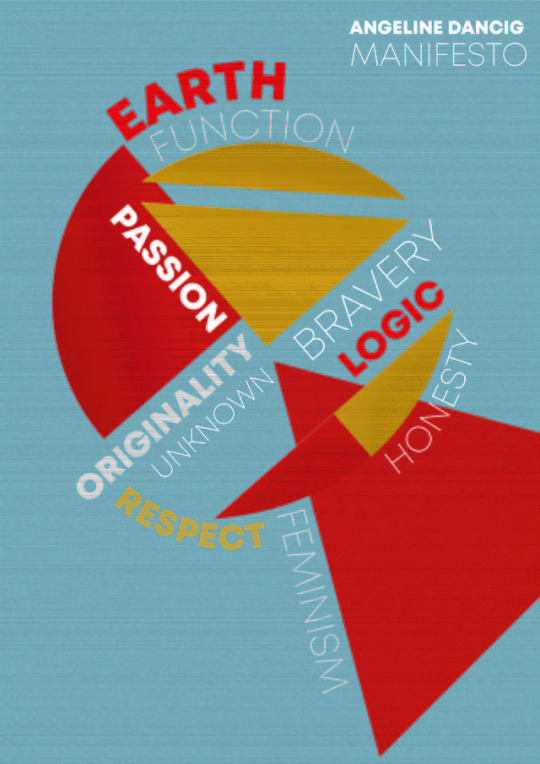

Bauhaus inspired manifesto poster by Angeline Dancig

I will care about the environment. I support vegetarianism because I know that animal agriculture is not sustainable. I will continue to educate people on the detrimental effects of farming on the earth in the hopes that our carbon footprint will one day disappear. I will also use eco-friendly techniques in my artistic practice.

I will be inspired by science and the unknown. While many fear what may or may not be beyond our world, I find the universe and astronomy fascinating. I will continue to learn about the planet and space in order to better understand where we came from and where we could go. The unanswered questions I have about the universe are a limitless source of inspiration for me.

I want to create functional and beautiful design. I do not want the things I create to further clog the oversaturated visual world we know. I want my designs to be meaningful and to be innovative solutions to the everyday problems people face. However, I also love beauty and I believe that practicality and artistry are not mutually exclusive.

I will not let fear hold me back. I often do not attempt things because I am afraid that I will fail or that I am not good enough. I will work on believing in myself and my abilities. I will not hold myself back for fear of not being accepted. This applies to my work and social life.

I will be original. I have never been the type of person who completely aligns herself with a particular trend. Rather, I will take trends and make them my own. I will continue to not let what is popular dictate what I wear, create or how I behave.

My work will push limits, but will not unnecessarily offend. I believe that work can be risqué and singular while still being respectful. I will be provocative only when it is necessary or creates value. I want to create content which people can relate to and I will strive to focus on my audience when creating.

I will use my passions and interests to guide my career decisions. I realise that I may have to do work that I do not necessarily love, however, overall, I aim to turn my talents and interests into jobs. I think that work is imperative to life and I want to enjoy whatever job I do one day.

My outlook will be open to changing, but I will not sacrifice logic and reason. My outlook on the world is heavily influenced by science and I want to continue to believe in the things that I can see and which can be proved. I am not religious or spiritual and I will not allow arrogance or ego to guide my beliefs.

I will be honest, but still kind. I will express my opinions as honestly as is possible in the particular situation. I will not allow what other people think to influence how I should feel. However, I will also keep in mind how I would want to be treated in every situation and make sure that what I say is purposeful and necessary.

I will never let my gender restrict me. Society still favours men, but this will not stop me from achieving my goals. I will not allow myself to be bullied or harassed and I will report sexist behaviour when I see it. I believe in the values of feminism and I will maintain behaviour which promotes equality and peace.

(587 words)

0 notes

Photo

Fig 1. Music video still, Fast car (Green Light 2017: 1:09)

0 notes

Photo

Fig 2. Music video still, Club bathroom (Green Light 2017: 2:20)

0 notes

Text

Analysis of Lorde’s ‘Green Light’ music video

This essay will discuss the music video of Lorde’s song, ‘Green Light’ (Lorde 2017: Online). A general background of music videos will be discussed. The lyrics of the song in relation to the video and the personal circumstances of the artist as inspiration will also be considered. Finally, the essay will elaborate on the cultural context it was created in, as well as the reception of ‘Green Light’.

The music video originated in the 1980’s and 1990’s (Mundy 1999: 27) which Berg claims brought “prosperity to a slumping record industry” (1984: Online). According to Vernallis, “music videos function in the form of narrative film”, meaning they tell stories (Vernallis 2004: Online). She also says that the artist first produces the song, and then the music video which indicates that the video is in response to the music (Vernallis 2004: Online). According to Goodwin, the direction of the music video depends on the genre of the song (Valdellós, López & Acuña 2016: 336). The importance of music videos can be illustrated by Aufderheide who called them trailblazers in terms of video expression (1986: 57-78).

When ‘Green Light’ was featured on the album Melodrama, it was the first time Lorde had released new music in three years (Shorey 2017: Online). Lorde has stated that the song is about her “first major heartbreak”. In an interview with Vanity Fair she said that she is “an introvert, a writer—just trying to translate what’s inside (her) chest” (Robinson 2017: Online), which illustrates that she writes about her own experiences. She has said that the record is an ode to the emotions felt around nineteen years old; being on her own for the first time and experiencing a multitude of very grown-up things (Robinson 2017: Online). It represents a new era of Lorde’s music which came as a result of entering a different phase of her life (Shorey 2017: Online).

According to Mcconnell, although the song is about a failed relationship, it also speaks to the overall message of Melodrama, growing up (2017: Online). Bradley interprets the song’s lyrics as the artist expressing unfamiliar feelings brought on by a new chapter (2017: Online). Lorde has also said that she was out of her comfort zone while creating it as it is not what she generally writes about (Donnelly 2017: Online). The evolution of her videos from her first at 16 years old, to the more visually in-your-face ‘Green Light’ at 20 years old, show Lorde’s personal growth as an artist (Trendell 2017: Online).

The director of the music video, Grant Singer, and Lorde met a few months prior to shooting it (Hogan & Pearce 2017: Online). Lorde has said that she and Singer were both “kindred spirits” and shared a connection (Shorey 2017: Online). The making of the video was a collaboration between the artist and the director (Hogan & Pearce 2017: Online). It was shot on 16mm film which Singer claims “has a thickness to it, and... feels timeless” (Hogan & Pearce 2017: Online). Although digital is cost-effective, film allows for a richer colour and more of a contrast, which most producers prefer (Phipps 2001: 8). “Film looks better because of grain, depth of field and emotion which video does not have.” (Phipps 2001: 8).

Many of the shots in the video were not scripted and portray Lorde improvising, something Singer describes as happy accidents (Hogan & Pearce 2017: Online). This method of improvisation appears to be used by many directors, including art director Adam Levite (Hanson 2006: 27). Levite has said that he creates a framework for “beautiful accidents” to happen which he then uses to make his videos (Hanson 2006: 27). As this was Lorde’s first video in a few years, Singer wanted for there to be a clear artistic distinction between her old and new work (Kaufman 2017: Online).

The video was filmed in Los Angeles’ MacArthur park (Shorey 2017: Online). Singer did not include any known landmarks as he did not want to restrict the video to a particular city (Hogan & Pearce 2017: Online). The video portrays her in the back of a car speeding through a city, which could represent how she has had to grow up quickly (Donnelly 2017: Online). Donnelly describes the video as Lorde moving into adulthood through heartbreak (2017: Online). Jack Antonoff, a collaborator of Lorde’s, makes a cameo playing piano in the bathroom of a nightclub in the video; a scene which Lorde said was “very important” (Trendell 2017: Online) since she has credited Antonoff with helping her channel her emotions through her music throughout Melodrama (Robinson 2017: Online). According to Lorde, the song alludes to someone who is broken and has lost control, which is clearly depicted in the video (Mcconnell 2017: Online).Throughout the video, Lorde’s dancing is co-ordinated with the vocals of the music which creates an “interconnected” performance, according to Singer (Kaufman 2017: Online). Donnelly describes the video as “a completely relatable scenario” (Donnelly 2017: Online).

In terms of the cultural context of Lorde’s video, the writings of Stuart Hall can be applied. Hall argued that culture cannot only be defined by the “educated élite’s” of society (Hsu 2017: 1-2). According to him, culture is “experience lived, experience interpreted, experience defined” (Hsu 2017: 1-2). Lorde used her experiences of loneliness and heartbreak to inspire ‘Green Light’ (Bradley 2017: Online). Having started making music as a teenager, Lorde had always written from the perspective of a young person (Robinson 2017: Online). Hassan and Katsanis propose the idea that teenagers internationally share a similar culture in terms of their lifestyles, including their appreciation of music (Kjeldgaard and Askegaard 2006: 231). Lorde wanted the culture of young people who listen to her music to be able to relate to the video, which is an honest interpretation of her life (Trendell 2017: Online). Lorde’s ‘Green Light’ video is a powerful example of her work as it speaks to the “universal truth” of moving on (O’Neill 2017: Online).

The music video, which was released on YouTube in 2017, received more than 60 million views in under 3 months (Shorey 2017: Online). There were people who interpreted ‘Green Light’ as a reference to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, but Lorde responded on Twitter by saying it referenced a traffic light more than the novel (Stumme 2018: Online). The video currently has almost 113 million views (Lorde 2017).

In conclusion, this essay attempts to explain the meaning behind Lorde’s music video for ‘Green Light’ by expanding on music videos in general. It illustrates that Lorde used the video to communicate her personal experiences in the context of youth culture and it elaborates on Lorde’s audiences’ reaction to her music video.

(1118 words)

Reference:

Green Light, 2017. Music video. Directed by Grant Singer. Universal Music New Zealand Limited.

0 notes

Text

A Biography of Lorde

This essay will discuss the life of singer/songwriter, Lorde. It will consider her early life and influences, the beginning of her career as a musician and her subsequent success. Finally, it will conclude with why Lorde is a creative inspiration.

Named Ella Maria Lani Yelich O’Connor, she grew up in a suburban area in Auckland, New Zealand (Shapiro 2014: 17). She was born to parents Victor and Sonja in 1996 and has two sisters and a brother (Shapiro 2014: 21-22). At ten years old, Ella was reading “grown up books” by Silvia Plath and Kurt Vonnegut and short fiction by Tobias Wolfe (Shapiro 2014: 30-31). She recalls being influenced by the minimal, sparse writing style of Raymond Carver which taught her that lyrics need to be sharp and potent (LordeVEVO 2016: Online). Her early musical influences, introduced to her by her parents, were artists like Cat Stevens, Fleetwood Mac and Neil Young (LordeVEVO 2016: Online). She was also influenced by soul artists Etta James and Otis Redding, and electronic musician James Blake (Recording Academy / GRAMMYs 2013: Online). According to Shapiro, she began performing in school competitions and at cafes around town (Shapiro 2014: 37-38). A video of Ella performing at a school talent show led to her getting a development deal with Universal at the age of 12 (Morris 2017: Online).

Through Universal, she began to collaborate with producer Joel Little and started writing and recording her own music (Shapiro 2014: 53-54). He “was able to help translate her razor sharp lyrics and melodic sensibilities into something truly special” (Author unknown [s.a.]: Online). Ella was inspired by her teenage years in suburbia “just hanging out” and, according to Sledmere, she developed a “brand of adolescent melancholia” ([s.a.]: Online). She has said that her lyrics were inspired by her friends, social situations and feelings of loneliness as a teenager (LordeVEVO 2016: Online). She chose her stage name, Lorde, inspired by the aristocracy and royals which had always fascinated her (Ray [s.a.]: Online). Lorde released The Love Club EP in 2013 (Permatasari 2015: 2). Her chart-topping single, ‘Royals', was inspired by materialism in American popular culture and “became an international hit” when it was released in mid-2013 (Permatasari 2015: 2-3). It charted at number one in the US making her the youngest solo artist to do so in history (Permatasari 2015: 2-3). Using her “voice of teenage cynicism” she would write a full-length album called Pure Heroine, featuring a new kind of pop (Sledmere [s.a.]: Online).

The album Pure Heroine was released in 2013 (Permatasari 2015: 2) and earned her four Grammy nominations (Shapiro 2014: 114). It was described by Morris as “spare electronic beats overlaid with... smoky, syncopated vocals, creating a sound that was part pop, part hip-hop, part jazz and entirely hypnotic” (2017: Online). In addition, ‘Royals’ won Lorde two awards at the 2014 Grammys for Best Song Of the Year and Best Pop Solo Performance (Ray [s.a.]: Online) and one of her upcoming US tours sold out in a few days (Shapiro 2014: 132). “… Lorde was hailed far and wide as pop’s antidote to its own artifice.” (Morris 2017: Online).

Then, after conquering the music world, Lorde took a hiatus (Morris 2017: Online). She went home to New Zealand and “slowed the pace of her life” (Lamont 2017: Online). She spent the next few years working with producer and Bleachers front man, Jack Antonoff, on her second studio album (Morris 2017: Online). According to Antonoff, while Pure Heroine was minimalistic in sound, her second album would include a broader range of instruments like acoustic guitar (Morris 2017: Online). She released Melodrama in 2017 and “was greeted with an overwhelmingly positive critical reception” (Ray [s.a.]: Online). Lorde stated that Pure Heroine was meant to immortalise her teenage years and that Melodrama is about “what comes next” (Lorde 2016: Online). While writing Melodrama, she was inspired by the “timeworn wisdom” of musicians Don Henley and Phil Collins (Morris 2017: Online). The album was ultimately about heartbreak but in a different way to musicians like, for example, Pete Wentz of Fall Out Boy (Sledmere [s.a.]: Online). “Lorde never falls into that masturbatory, masculine trap of complete self-deprecation”, which supports Lorde’s reputation as an unorthodox and original artist (Sledmere [s.a.]: Online).

It is this unconventional and alternative quality which makes Lorde‘s work extraordinary; evident by how her music falls into multiple genres including dream-pop, rock and indie-electro (Permatasari 2015: 2). She “concocted her own brand of sophisticated, observational and distinctive pop music” (Lorde [s.a.]: Online) which led musician David Bowie to say that listening to her felt like listening to tomorrow (Shapiro 2014: 110-111).

Lorde was able to “bring a fresh sound to the music industry” which she did from the age of sixteen (Deihl 2013: 8). “In 2013, she was named among Time 's ‘most influential teenagers in the world” (Permatasari 2015: 2). Lorde refused to let other people control her music; she wanted to have a unique, authentic voice (Morris 2017: Online) which allowed her to go from “a completely unknown” teenager from New Zealand to a pop star (Mitchell 2016: 51-70).

Lorde’s universal appeal is honed from her creation of a new style of pop music through experimentation and being influenced by a multitude of musicians. She drew on her experiences as a teenager and as a young adult to inspire two widely celebrated albums, which have successfully established her in the ranks of renowned musicians and as a modern-day creative hero.

(939 words)

photograph via weheartit.com (https://weheartit.com/entry/299895901)

1 note

·

View note