Ania (she/her) | 25 | Poland Multifandom BlogDeal with itGravity Falls, MCU, Star Wars, Mission: Impossible, Stargate, Supernatural, Steven Universe, Adventure Time, Portal, Red Dead Redemtion and more! -ART BLOG- Artanyan.tumblr.com

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

We've lost some of the greatest posters of our generation to employment

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

911 usually: firefighters dealing with extreme trauma both on the job and off

also 911 usually: how’s this group of gay people going to defeat the 22 MILLION BEES

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

The thing about 911 is that the shipping drama and discourse surrounding it completely belies how insane this show truly is. A man is attacked by a shark on the freeway. Ghosts are probably real, and so are curses. The most recent season opens with a bee-nado that segues into a plotline about an autistic half-orphan child landing a broken plan. The most dramatic moment between the fandom's favorite ship is one of the characters getting shot by a sniper in broad daylight in the suburban streets of Los Angeles. Buck's introductory scene of the entire show is him stealing a firetruck to have sex with a Tinder hookup. The fire captain's backstory is an addiction that led to the death of 148 people. He's best friends with his wife's ex-husband and once proposed to said ex-husband's boyfriend on his behalf while that boyfriend was performing brain surgery on a man in the middle of a burning building. There's a guy who sneezes every time he lies and then lies so hard he almost dies. One of the main characters gets rebar impaled through his skull and is back to work the next month with no lasting side-effects. They basically never fight fires.

#this show is crazy#this isn't even one twentieth of all that craziness#surreal reality#oh and it has insane directing choices#a lot of weird zoom and pans and crops#i love it#i was screaming at the tv every ten minutes

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

Would you like to take part in a survey on fandoms for my master’s thesis? It's completely anonymous. You just need to be 18 years old or older. Your participation would be a great help, thank you💙

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Never going to get over the fact that I went into the Mission Impossible films expecting Ethan Hunt to be this macho man that’s peak “made by men for men” and instead got absolutely slapped across the face by the fact that he’s in fact not that… he’s just this sad little guy who loves his friends a little too much and runs more than any one person should

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

@ghostbird-7 linked me to the GQ write-up about Christopher McQuarrie and I'm reeling. I'm losing my entire fucking mind.

I've felt an admiration and kinship for McQ's philosophy on creating art for years now and the specific way he does it, his journey from artist-first to the guy who is parachuted in to save movies from themselves to a tradesman and the back to an artist, the focus on methodology. I'm going to expire.

this one fucking bit:

McQuarrie began to notice patterns. Mistakes that were made, over and over again. Studios soon recognized this particular talent. Once, McQuarrie told me, in his capacity as a movie ER doctor, he was parachuted in on two separate films in distress, on which two totally different filmmakers both had an Apocalypse Now poster in their office. “And I said, ‘Let me tell you how to make Apocalypse Now. Let me help you because it’s so simple. First, make The Godfather, then make The Conversation, then make The Godfather Part II. Then take all of your personal capital and all of your professional capital and gamble that and your marriage and the life of your leading man and your sanity on a movie about a war that nobody wants to remember. And then spend years shooting it and put it in cinemas and no one will come and it will take decades before people recognize what it is. That’s how you make Apocalypse. Now let me tell you something: You’re not making Apocalypse Now.’ ”

because its so simple MCQUARRIE YOU MASSIVE BITCH. /fans face

ENTIRE ARTICLE UNDER THE CUT bc man that fucking paywall is a bitch to get around

When it comes time to start a new Mission: Impossible movie, the first thing that happens is Tom Cruise, the star of the franchise, and Christopher McQuarrie, its longtime writer-director, sit down together and they ask each other: What do you want to do? The answer is inevitably: something difficult and dangerous.

Years ago, when Cruise and McQuarrie were beginning to sketch out the plot of 2018’s Mission: Impossible—Fallout, Cruise proposed a helicopter chase: his character in the films, Ethan Hunt, pursuing a bad guy, played by Henry Cavill, while both of them were aloft. As a rule, in Mission: Impossible, stunts are real: meaning they are performed by the actual actors involved, at least when possible, and when they are being done by Tom Cruise, that means all the time. “He’s the only actor in the world who is actually going to do everything,” Fraser Taggart, the series’s director of photography, told me.

In the Mission: Impossible franchise alone, Cruise has climbed the shiny glass sides of the Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building; hung from the side of an A400 military transport plane as it took off; and ridden an actual motorcycle off the edge of an actual Norwegian cliff. He has a commercial pilot license. He is one of 36 people in history to be named an honorary US naval aviator. He can parachute and BASE jump and free dive. But one issue with this particular idea for Fallout was that Cruise, at the time, was not trained as a helicopter pilot. So Cruise and McQuarrie made inquiries, and they were told that at eight hours a day, seven days a week, it would take three months to get Cruise up to speed. Cruise asked: What about the other 16 hours in a day? A month and a half later, he was ready to fly.

The second problem with the idea was that it was so perilous that most countries wouldn’t allow Mission: Impossible to try it within their borders. This is the next conversation McQuarrie and Cruise have. “You’ve got to figure out: Where in the world are we going to shoot this?” McQuarrie said recently. “Well, we’re going to go (a) where Bond isn’t. And (b) where Fast and Furious isn’t. And (c) where Mission has never been. That Venn diagram says: Here’s where you’re shooting. Provided the State Department even allows you to go there.”

With the helicopters, McQuarrie and Cruise tried India first, but “when we told them what we were going to do,” McQuarrie said, “they were like, That’s not happening here.” Finally, they found a friendly government in New Zealand, which said, according to McQuarrie: “Shoot it away from population, and just know if you fly in this glacier and anything happens, there’s no one that can come and get you. You’ll be there forever. They’re going to fly over it and drop a plaque.”

With the location secured, McQuarrie and Cruise got to work. In the sequence they’d planned, Hunt is pursuing a turncoat named Walker, played by Cavill, who is holding the detonator to two nuclear bombs. To film the chase, McQuarrie and his cameraman followed Cruise in a second helicopter. Once in the air, the production followed a strict fuel countdown, meaning they only had so much time in the sky, but the shot was tricky to get right. McQuarrie, over the radio, would give Cruise direction: left pedal, right pedal, until Cruise had flown himself into the frame. “Tom is lining up the helicopter in a camera he can’t see,” McQuarrie recalled. “And I said, ‘That’s your mark. Maintain it.’ The reason it’s always in the frame is because Tom Cruise is both flying the helicopter, looking over his shoulder so the camera can see him, and acting. He’s doing all of that at the same time.”

Simon Pegg, who plays Benji Dunn, a member of the IMF, or Impossible Mission Force, in the series, told me he often feels “a sense of quiet dread” when the production is away attempting one of these sequences. For this one, Pegg said, “I remember when we said goodbye and Tom was going off to do all this stuff with Henry, I said, ‘See you in London. Or maybe not.’ ”

McQuarrie and Cruise have now been working together for nearly two decades, beginning with 2008’s Valkyrie, which McQuarrie wrote and produced, and Cruise starred in. Their partnership has become one of the most productive and lucrative in Hollywood history. And at its center is Mission, as everyone involved calls it—a franchise unlike any other. Based on the TV series from the 1960s, the basic ingredients are almost camp: Each time out, Ethan needs a mission, which will be relayed via a self-destructing device. At some point, someone will wear a latex mask of a face that is not their own. The plots will be baroque; the exposition will come in 40-foot waves.

And yet in its sheer scale, its locations, its dedication to practical effects, and most of all its star, Mission is unmatched. Since McQuarrie came aboard—first as an uncredited screenwriter on the 2011 Mission: Impossible installment Ghost Protocol—the series has also distinguished itself as the rare action franchise about, for lack of a better word, adults. One unofficial rule of Mission is that Ethan Hunt can’t want to do any of the insane things he has to do (ride a motorcycle off a cliff, hang off the side of a plane in midair, etc.), because what normal, mature person would? The primary emotions Hunt seems to feel are guilt, grief, and fear. Just like the rest of us.

To these movies, McQuarrie brings a unique and singular skill set: screenwriter (he won an Oscar, at age 26, for the second Hollywood film he ever wrote, The Usual Suspects), producer, star-handler, director, fixer, stuntman. The producer Jerry Bruckheimer, who worked with McQuarrie on Top Gun: Maverick, told me: “When you look at the town, there are maybe 10 really gifted writers, and maybe 10 really gifted directors, that you can rely on to make something that the audience is going to love.”

McQuarrie is on both lists. And though he tries not to talk about it much, he is also on a third list, as the guy you call when your movie, or your script, isn’t working but the train has left the station and the film is already in production. Sometimes he is credited for this work—as on Edge of Tomorrow or Top Gun: Maverick—and sometimes, as on World War Z, or Rogue One, he is not, which suits him fine.

For the one sequence in Fallout with the helicopters—a scene that would ultimately run around 12 minutes in the film—they shot about 80 hours of footage, Mission’s editor, Eddie Hamilton, told me. Eighty hours. While director and actor hovered in the air. In a canyon where if something went wrong, there would be no escape. “If you want to know why I’m working for Tom for 18 years and other people aren’t,” McQuarrie said, “lots of directors will do that once. They don’t ever want to fucking do that again.”

One day recently, McQuarrie was at home in London, where he lives in a two-story apartment near Hyde Park, racing to finish the latest and possibly last installment of the franchise, Mission: Impossible—The Final Reckoning. (McQuarrie and Cruise both remain coy about whether this is, in fact, the final Mission film.) It was a warm, quiet Saturday, and McQuarrie and Hamilton, his editor, were ensconced in an editing bay on the second floor of the apartment, working through the latest version of the iconic This message will self-destruct brief that more or less begins each Mission movie.

McQuarrie, who is called McQ by his friends, has an emphatic gray sweep of hair, clear-framed glasses, and the distinct and easily legible features of an iPhone emoji. He gestured at the scene on the monitors in front of him and Hamilton. “It’s a giant exposition dump,” he said. “And it’s always excruciating because information is the death of emotion.” Mission movies tend to be dense with plot that even the films’ creators don’t expect the viewer to fully retain. “I’m acutely aware of what I think you are and are not listening to,” McQuarrie told me. “I actually don’t rely on you to pay full attention. I kind of rely on you to drift in and out and get key things.”

McQuarrie began as a screenwriter: worshipful and intensely protective of the words on the page. But in time, and “as I started to understand my job as a director more, I started to understand, you got to let go of the word,” he said. Mission is made for massive global audiences. “Tom and I are talking all the time about the fact that every word you write is a word someone has to read in some part of the world. And that when they’re reading the subtitles, they’re actually not seeing the image. So my images have to tell the story and the words become music.”

McQuarrie had Hamilton cue up the sequence from the beginning and play it for me. “Good evening, Ethan,” intoned Angela Bassett, who plays the president of the United States in the film. Cruise silently watched a monitor as Bassett laid out his character’s history, where Hunt was now, and the stakes of his latest mission. Montages of destruction, nuclear warheads, scenes from past Missions played on the screen. “We’re motivating cuts based on specific words,” McQuarrie explained. “So even if you’ve tuned out, when you hear sacrifice, you might tune in for key words.”

The studio, Paramount, had recently screened Mission: Impossible—The Final Reckoning for a test audience in Paramus, New Jersey, a location chosen as a literal and cultural midpoint between London and Los Angeles. McQuarrie—unlike many directors, who fear getting feedback that might lead to the studio mandating changes to their film—loves a test screening. “Filmmakers are terrified,” he said, “and rightly so, because not all filmmakers have control of their movie.” But Cruise, who is also the lead producer on the Mission: Impossible franchise, has final cut. So they welcome the information, which they are then able to respond to as they see fit. In this case, audiences had been slightly confused by the mission brief, and so McQuarrie and Hamilton were trying to slow it down and leave them with the desired impression.

After McQuarrie played the sequence once for me, he turned and asked: “What did you take from what you just watched?”

I stammered out what I understood: “Artificial intelligence is trying to use nuclear stockpiles to destroy—”

McQuarrie gently cut me off. “Thanks. That’s all I need you to retain.”

Hamilton cued the scene again and they began going frame by frame, trying to make sure that the images were doing what they could not rely on the words to do. At one point, on a close-up of Cruise, McQuarrie asked Hamilton to pause the scene. “I don’t feel like he’s listening,” McQuarrie said, studying Cruise’s face. “I feel like he’s drifting.”

Hamilton, on another monitor, called up more footage from the scene. “So here now we enter the library of Tom Cruise’s reactions,” McQuarrie said. When this was originally shot, McQuarrie said, Cruise was listening to something else entirely. “It was completely different,” he said. “What we’ll do is, the camera will just drift and Tom will just interact with the camera. And he’ll give you this library of options because he knows full well it’s probably all going to get rewritten.”

Mission scripts are notorious for changing. “Tom likes to feel the film evolve, rather than have a set script and a schedule locked in,” Pegg told me. “It’s a very meta experience,” Erik Jendresen, who cowrote the last two, said. “Because as the screenwriter, me and Tom and Chris, we’re like the IMF team. We’re working under a ticking clock. The stakes couldn’t be any higher. And you’re needing to pivot constantly.” McQuarrie is sensitive to the impression this can leave. “We are not making it up as we go along,” he said. “But we are constantly pushing ourselves to make it better, to make it more immersive, more resonant, more engaging. We don’t trust that just because somebody says these lines on a piece of paper that you’re going to feel those things.”

But a lot can change in the pursuit of a feeling. One of the first things McQuarrie did when he joined the franchise, mid-production, on Ghost Protocol, was rewrite the entire backstory of a character named William Brandt, played by Jeremy Renner. The actor, who had already shot many of his scenes, was initially furious, according to McQuarrie. “Renner was saying, ‘I’m going to free-fall.’ He said to me, ‘But wait, I’ve been playing this whole other character.’ And I said, ‘But I watched all your dailies and all the emotions are the same. What motivated you in that scene doesn’t matter. The emotions you’re communicating are what matters.’ ”

Actors get used to it, McQuarrie said, but the learning curve can be harsh. “Once you start to see the results—Vanessa Kirby on Fallout, Rebecca Ferguson on Rogue Nation, they were all new to the process, and they were all in some way quite understandably destabilized,” McQuarrie said. “But then they see the beginning, middle, and an end. So when they come back for another movie, by the time Vanessa came back for Dead Reckoning, everything changed one day; we had an idea, we rewrote the scene that morning, and I said, ‘Look, I’m sorry, but you’ve got this big thing now.’ And she goes, ‘It’s Mission. I totally get it.’ ” Hayley Atwell, who joined the franchise on Dead Reckoning, told me that the “ever-changing, ever-expanding challenges” of doing things this way used the same muscles that she’d built, not in other movies, but in live theater.

Because of the constantly evolving nature of the Mission scripts, they usually shoot exposition in places they can return to—and not, for instance, on the top of a mountain. “Anytime you have big information scenes, anytime you have exposition, plot, you put them in small rooms, cars, phone booth, you put ’em into a place that you can easily repeat and go back to,” McQuarrie said, “because you’re always going to be changing the plot to accommodate the emotion, rather than the other way around.”

In the edit bay at McQuarrie’s home, Cruise’s face filled the screen in mid close-up, eyes darting, brow furrowing, head bobbing. Cruise is famous on Mission sets for knowing exactly where the frame is: He can indicate the top and bottom of a shot from 30 feet away. “See these very subtle movements he gives,” McQuarrie said. “He’s not doing a big thing. He knows the focal length of that lens and how much it picks up.” When a new actor joins the Mission: Impossible franchise, one of the first things McQuarrie does is sit them down and talk to them about lenses. “Now, when I’m directing Hayley Atwell,” McQuarrie said, “I don’t say, ‘I want your character to feel this, that, and the other thing.’ I point to the lens and say: ‘It’s a 75-millimeter.’ ”

Hamilton and McQuarrie started the scene again from the top. A few minutes later, McQuarrie’s phone rang and the letters TC appeared on the screen. “I’ll be back,” he said.

Before Mission: Impossible, before Tom Cruise, before he won a screenwriting Oscar at 26, McQuarrie was a security guard at a movie theater. “That was my film school,” he said. “I spent four years watching the audience. They were my focus group.” McQuarrie grew up in New Jersey and went to high school with the actor Ethan Hawke, the director Bryan Singer, and the musician James Murphy, of LCD Soundsystem. Because of this, a career in the arts never seemed all that far-fetched. “Bryan was always making movies. James was always making music. When Ethan got cast in Explorers, I was 14, Bryan was 16. James was 12. That made it real—that made it something that could happen. And frankly, it was more real to me than going to college.”

It was Singer who gave McQuarrie his first break in Hollywood when he commissioned McQuarrie to write what would become Singer’s first film, Public Access, in 1993. At the time, McQuarrie, who never did go to college, was doing odd jobs. Public Access screened at the Sundance Film Festival, and won a prize there, but the film never found a distributor. Then McQuarrie came back to Singer with an idea of his own, for a movie called The Usual Suspects, a film told primarily through the interrogation of a small-time criminal named Verbal Kint, played by Kevin Spacey, whose increasingly convoluted tale turns out to be—unbeknownst to his interrogator and the audience—an elaborate fiction.

McQuarrie wrote the first draft of The Usual Suspects in two weeks. The movie has an unorthodox structure; the film opens on the ending of the B-plot, about a group of criminals who are forced together to do a job, and then basically plays in reverse to hide the ending of the A-plot, the true identity of Verbal Kint, which is revealed in the film’s final frames. The end is the beginning is the end. “Suspects is pure structure, pure dialogue,” McQuarrie said. “It’s pure screenplay. Suspects is the rare example of a screenplay that is both readable and shootable. It’s also a script everyone in Hollywood passed on. Everyone. And it’s quite a fluke that the movie ever got made.”

There is an aphorism McQuarrie is fond of: “Writing is pushing a boulder up a mountain. Directing is running down the mountain with the boulder rolling after you.” In the decade after winning the best original screenplay Oscar for The Usual Suspects, he did a lot of pushing. “I thought the Oscar represented power that I could now make something that I wanted to make,” McQuarrie told me. “That wasn’t true. What it meant was I could get paid more money to write the movies they wanted. Nobody wanted my movies.”

McQuarrie had big ambitions and scripts of his own. But what he was actually doing was either joining ailing productions to help fix their scripts, or working in studio development, meaning he was being brought in to come up with ideas and treatments for projects conceived of by executives at various studios and production companies. In practice, very little of it ever saw the light of day. “I spent 10 years writing movies that were never going to get made,” McQuarrie said, “to finance the development of my scripts, which no one would ever make.”

In 2000, frustrated with his inability to make something of his own, McQuarrie wrote another crime film, The Way of the Gun, with plans to direct it, with Ryan Phillipe and Suspects actor Benicio Del Toro as his two leads. The Way of the Gun—about two bumbling criminals who abduct a surrogate mother and hold her and her unborn child for ransom—was deliberately antagonistic: It broke all the rules that McQuarrie had been forced to follow about sympathetic characters, about plot development, and about taking care of the audience, and when it came out, audiences summarily rejected it. “I directed an eight-and-a-half-million-dollar movie that I didn’t want to make,” McQuarrie said. “But it was my only opportunity. And I made it with both middle fingers extended, and the movie didn’t work, and the business said, ‘Thanks very much, that was your shot.’ And I was in director jail, and that’s where I remained for 12 years.”

While in director jail, McQuarrie worked on many movies, and was fired off of many movies. Screenwriting is a brutal business. “Writers, consciously or unconsciously, we are held in contempt,” McQuarrie said. “The movie can’t happen without us, but we are not why a movie happens. We’re not stars, we’re not directors. We’re the nerd at the party and we have the car. You’re not getting home without us. That breeds a kind of resentment.” McQuarrie even went so far as to quit the business at one point. But he was also developing a reputation as a troubleshooter and a fixer. (McQuarrie was once asked to write a script about the making of the Transcontinental Railroad, but for cheap, meaning, somehow, it would need to be shot inside, without showing all that much of the actual railroad—“And I figured out how to do it.”) McQuarrie, Pegg told me, “thrives with a problem. I think McQ loves a crisis more than he loves a blank page.”

What McQuarrie saw during his years in the wilderness were men and women—screenwriters, directors, producers—under duress, making unwise decisions, particularly on movies on the scale of Mission: Impossible. “A lot of these big tentpole movies,” McQuarrie told me, “how they work is you take a director who’s only made smaller films but has had success, and somebody does the math that says, ‘Hey, that person made a $5 million movie that made $50 million, now let’s give them $200 and they’ll make a billion.’ That’s actually not how it works. Because that person is leaping from an independent mindset into a massive commercial mindset without having had any education of the kind of movie they have to make at that number.”

McQuarrie began to notice patterns. Mistakes that were made, over and over again. Studios soon recognized this particular talent. Once, McQuarrie told me, in his capacity as a movie ER doctor, he was parachuted in on two separate films in distress, on which two totally different filmmakers both had an Apocalypse Now poster in their office. “And I said, ‘Let me tell you how to make Apocalypse Now. Let me help you because it’s so simple. First, make The Godfather, then make The Conversation, then make The Godfather Part II. Then take all of your personal capital and all of your professional capital and gamble that and your marriage and the life of your leading man and your sanity on a movie about a war that nobody wants to remember. And then spend years shooting it and put it in cinemas and no one will come and it will take decades before people recognize what it is. That’s how you make Apocalypse. Now let me tell you something: You’re not making Apocalypse Now.’ ”

(ARC NOTE: jesus fucking christ)

What McQuarrie would try to do instead was identify whatever the filmmaker had done that was unique to the genre or the franchise they were working on. Something that was their signature. And he would say, “ ‘That’s your stamp. Now you’ve got to make a billion dollars. Come with me if you want to live.’ And in both cases the directors did not listen. And in both cases the films were taken away from them. Other filmmakers came in and finished those films.” McQuarrie didn’t blame the directors. He blamed the system. “The problem is that they were given an opportunity, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” McQuarrie said, “before anybody sat down and educated them and said, ‘Listen, before you do this, here’s the reality of making movies like this. Are you sure you want to do it?’ And that’s what doesn’t happen. There’s not a system that educates those people.’ ”

McQuarrie knows this because he was one of those people. What changed that fact—and what got McQuarrie out of director jail and development hell—was Tom Cruise. McQuarrie and Cruise met in 2006, as Cruise was circling the lead role in Valkyrie, a movie about the failed assassination of Hitler that McQuarrie had written with the hope of being able to direct it. But Hollywood can be unforgiving. Singer, McQuarrie’s old classmate and collaborator, was also interested in directing the film, and so Singer—a more proven and financially successful filmmaker—became the director instead. (Singer has been accused of sexual assault in multiple lawsuits that were either settled or dismissed, and has maintained his innocence. He hasn’t directed a film since 2018. “My relationship with Bryan is pretty complex,” McQuarrie told me.) Cruise, according to McQuarrie, had two stipulations regarding Valkyrie. The first was that they spend more money on the film. “He said, ‘Guys, you’re blowing up the 10th Panzer division in the first 10 minutes of your movie; you need more money.’ And I said, ‘What’s the compromise?’ And Tom said, ‘There is no compromise. We’re making this movie. We’re going to make it for the widest audience possible. We’re going to make the most emotional version of this movie that we can.’ ”

The second stipulation was that McQuarrie, whom Cruise was growing to like and trust, join Valkyrie as a producer—a job he’d never done before. McQuarrie said yes anyway. “I went to work every day fully expecting to be fired,” he told me. He and Cruise are still working together 18 years later. “And it’s very important to point out that in between The Usual Suspects in ’95 and Valkyrie in 2006, a stack of movies this high, projects that I was called into rewrite, movies that never got made, not one piece of wisdom or applicable knowledge ever came from anyone in any of those meetings, ever,” McQuarrie said. “The truth of the matter is, other than what I brought to storytelling when I wrote The Usual Suspects, everything I learned about movies I learned by making movies with Tom.”

After Valkyrie, McQuarrie’s career was reborn. Suddenly, he was being brought on to write or help fix movies that were actually being produced: Edge of Tomorrow, World War Z, The Tourist, Rogue One, Top Gun: Maverick. In 2012, he directed Cruise in Jack Reacher; three years later, on the heels of doing the uncredited rewrite on Mission: Impossible—Ghost Protocol, McQuarrie became the director of 2015’s Mission: Impossible—Rogue Nation, after Cruise called the head of the studio and said that’s who he wanted in the chair.

Jerry Bruckheimer told me the secret to McQuarrie’s success in the latter half of his career was simple: “It’s because he loves it. He loves entertaining audiences. He loves big movies. You’ve got to love it. You bring in certain writers who want to write a big movie but don’t really care about it, you know, or understand what it is. They’re guessing.” McQuarrie is not guessing.

In London, over dinner, I asked McQuarrie to walk me through the making of a single stunt in the newest Mission: Impossible film. In Final Reckoning there is a sequence in which Cruise hangs from the side of a biplane, before leaping onto a second biplane, all in midair. An image from this scene is on the poster; pieces of it are in the film’s trailer. (This is the core of the Mission appeal: The thing the filmmakers care about most is the thing audiences care about most too. The movie is the marketing; the marketing is the movie.) The practice of going out onto the wing of a flying airplane is called wing walking, and that is who Cruise went to first: some wing walkers. “They said, ‘What do you want to do?’ ” McQuarrie told me. “And Tom said, ‘I want to be between the wings of the plane holding on to the tension wires, and I want to be in zero G between the wings.’ And wing walkers who do this for living said, ‘That will never happen. You can never do that.’ And Tom said, ‘All right, well, thank you very much for your time.’ ” And he and McQuarrie went and found some different wing walkers.

During the reporting of this article, I heard stories like this a lot. (Okay, one more: During the shooting of Fallout, McQuarrie told me, Cruise broke his ankle. “A doctor, a sports specialist, said to Tom, ‘It will be six months before you can walk. It’ll be nine months before you can run, if you ever run again.’ And Tom’s response was, ‘I don’t have time for that. I’ve got six weeks.’ And six weeks later, he was climbing Pulpit Rock on a shattered talus bone.”) If you’re wondering what Cruise has to say about all this, so was I. In time, I was invited to ask him a few questions via email. What makes Mission: Impossible…Mission: Impossible?, I wrote to him. Is it the process? The protagonist? The controlled chaos of the production? The stunts? The locations? The scale? “Dear Zach,” Cruise wrote back. “I don’t quite know how to answer this. Maybe it is all of these things and more.”

Mary Boulding, Mission’s first assistant director, told me Cruise has a saying on set: “Don’t be careful. Be competent.” So what the production did next, for the biplane sequence, was start building the stunt, piece by piece. They started with: Just get Cruise out on the wing. How far out could he get? How many G’s could he take once he was out there? “Now there’s a moment,” McQuarrie said, “where Tom’s laying across a cable and the plane goes into positive G’s, which means your whole body is being forced earthward. He’s laying on top of a cable, which means his organs are being pushed past either side of the cable. And if you go too far, the cable’s just going to cut you in half.”

It was at this point that I asked McQuarrie where his heart and mind typically were while shooting sequences like this one. During the A400 stunt, years ago, McQuarrie would sometimes black out from the stress as they waited to attempt it, he said. “If you want the summary, you’re the frog in the pan of water,” he told me. “You don’t realize the water’s boiling until you’re in it and it’s boiling. At which point you better figure out how to survive in boiling water or somebody’s going to be eating your legs and you develop a very thick skin.”

They decided to shoot the biplane sequence in South Africa, just after the rainy season there, because the land would be abundantly green. That also meant it was cold. “If the temperature changes two degrees Celsius, Tom will be hypothermic after 12 minutes on the wing,” McQuarrie said. Cruise had no radio in his ear. So he and McQuarrie, who shot the sequence from a helicopter that hovered so close to the plane that McQuarrie could read Cruise’s airspeed in the cockpit, devised a set of hand signals. “The wind is hitting him not only at the speed that the plane is flying but the wind coming off the propeller. It’s hitting him at well over a hundred-plus miles an hour.” At that speed, air is actually hard to breathe. “There were times when Tom would have to lay down on the wing to rest between takes,” McQuarrie said. “You can’t tell if he’s conscious or not. And unless Tom pats the top of his head”—their hand signal for stop —“it’s like, keep rolling.”

Cruise’s plane was also flying frighteningly low, McQuarrie said. “A plane flying at altitude, safely, is the most boring thing imaginable. You watch Top Gun: Maverick, the reason why we’re flying in that canyon, the reason why Star Wars flies in that canyon—planes are only cool when they’re flying low. No matter how fast they’re flying. Now in Top Gun, they were flying, at times, 50, 60 feet off the deck. When you’re in a biplane that can’t go Mach 2, you’ve got to go lower. The margin of error is zero. The power on these planes, they’re at full throttle, which means if there’s a downdraft or a thermal, there is no more oomph to get up. You go down and that’s it. I’m directly behind it. He goes down, I go down. Our crew goes down.”

In this way, over the years, McQuarrie has become kind of a stuntman too. Where Cruise goes, McQuarrie goes. Even in midair. “There is not enough room in this article for me to fully communicate and give justice to all of the things that Christopher McQuarrie is, does, and has done,” Cruise told me.

Despite the danger, McQuarrie seems to love the chaos of the life he’s fallen into. The bad luck, the broken bones, the close calls. “It’s weird how the content of these things mirrors the making of them,” Jendresen, the screenwriter, told me. McQuarrie encouraged me to rewatch the last scene of Mission: Impossible—Fallout, which they’d shot on film. Cruise’s Ethan Hunt, after his helicopter ordeal, awakens to find all his friends around his hospital bed. His whole body is in pain. “Don’t make me laugh,” he says, and then there is a flash of light, and the screen goes dark. Cue the Mission theme.

But that flash was not planned, McQuarrie told me. What you’re seeing is the most basic accident you can see on a film set. “There is nothing more Mission,” McQuarrie said, grinning, “than the camera rolling out of film on the last shot.”

(((THANK YOU ZACK BARON FOR THE BEST FUCKING PROFILE EVER HOLY SHIT))

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is real? Ohh my gosh, please let this be real

i don't post often but new 17776 coming soon? hi

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

i'm not very big on putting stickers on my stuff, but i think an iFixit sticker on a Framework laptop in the shape and position that you typically find OEM laptop stickers in is too perfect not to do.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dracula and Jonathan’s Tango - from The Polish National Opera production of ‘Dracula’.

With Choreography by Krzysztof Pastor and Music by Wojciech Kilar.

85K notes

·

View notes

Text

sometimes you just want to look at the qing dynasty jadeite cabbage again

51K notes

·

View notes

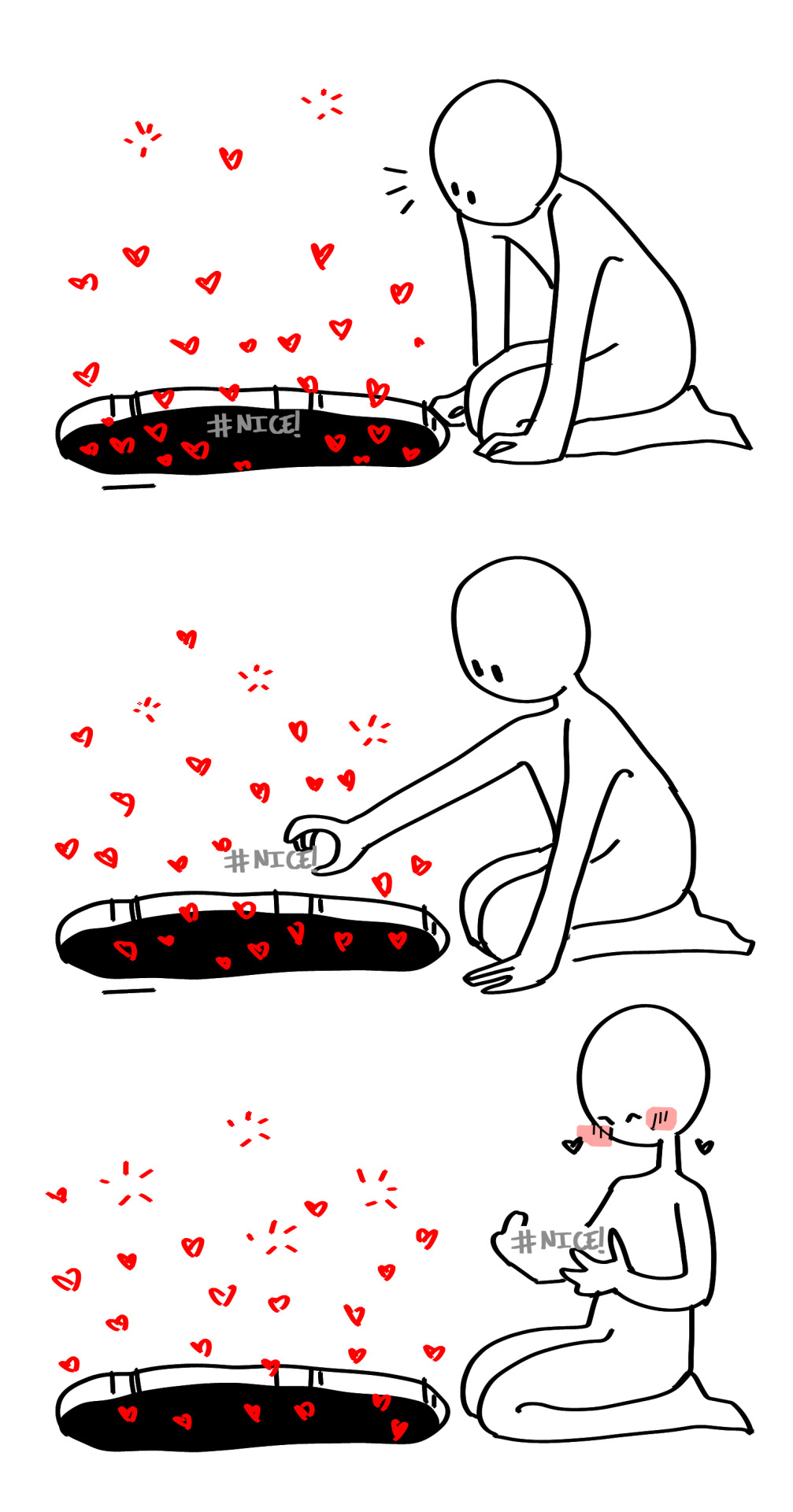

Text

No one owes artists anything.

But existence is lonely and sometime you throw hours and hours of effort into a void, on the slim chance it will say something back.

50K notes

·

View notes

Text

I love watching the behind the scenes footage and interviews of Mission Impossible movies because they’re all like

Director: I was up all night before we filmed this vomiting and shitting my pants and I literally had to cover my eyes while it was happening because I was so worried I would kill the biggest movie star in the world.

Tom Cruise: 😁 I love my team 🥰😍 we trained for months with the best of the best to do this ✅ I had total faith in them👊 and it looks sick as hell 😎 let’s do another take

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Old Portal2 fan art from *checks Procreate statistics* THREE YEARS ASO???

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

My friend made me add a happy end to this—— [link]

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

this photo is actly killing me 😭

the way ethan's looking right past grace at benji 😭😭

255 notes

·

View notes