Gabbomatic's media analysis blog, with an emphasis on Japanese animation.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Note

Posted this to the wrong blog lol.

Would you say that The Handmaid's Tale is a good book? Why or why not?

I liked it. From what I remember it’s an extreme “what if” scenario of what would happen to women if certain conservative ideologies reached their ultimate, fascist extremes while still maintaining a solid foot in recognizable reality. My (probably quite limited) take was that it’s a good way to scare girls into actively considering what certain people’s views - usually packaged nicely - would demand of them. It’s a feminist horror story.

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

Will you write anything about Psycho-Pass on here?

I actually am planning a project Psycho-Pass (as well as a few other shows) during the next few months! It'll be tying into my coursework this semester.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm not quite sure if this is your thing, but is it okay if i make a request for you to recommend some pieces/links about traditional japanese literary symbolism? what I mean is like "in the west, apples traditionally represent such and so, but in japanese culture, apples are often associated with this and that". i'm trying to research the subject, but i keep coming up short in my searches.

Unfortunately I don't know much on this subject. It might help you to check out Charles Dunbar's (@studyofanime on twitter) work. He works with Japanese mythology and has links to lots of primary sources on his blog. A lot of cultural symbolism is rooted in their early mythology. Godspeed!

11 notes

·

View notes

Link

I also wrote a review of Haruki Murakami's newest novel, Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, for my school paper.

#Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage#haruki murakami#colorless tsukuru tazaki#swarthmore college

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

DRAMAtical Murder is currently streaming on Crunchyroll. ...

Catch-up linking to my ANN stuff.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Sailor Moon Crystal is currently streaming on Crunchyroll. ...

Catch-up linking to my ANN stuff.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

In this Terror in Resonance episode, the band breaks up, the world spins off of its axis, and regular-Tokyo is about to explode. It's good, is what I...

Catch-up linking to my ANN stuff.

1 note

·

View note

Link

In the beginning, Terror in Resonance is about two teenagers who want to blow up Japan. Nobody knows why - not even the viewer, for a couple of episodes...

Terror in Resonance coverage is now on ANN!

(I don't think I'm doing more Aldnoah. Zero that show has been both stalling out and shitting the bed during the last couple of episodes.)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

So there's a reason I haven't been updating

Summer's coming to an end and all of my time is about to be sucked up by schoolwork. Long pieces are out for now, but - good news - you'll still be able to read my writing because I was hired to do episodic reviews for AnimeNewsNetwork.com. I'll be debuting over the next few days there with pieces on Terror in Resonance, DRAMAtical Murder, and Sailor Moon Crystal. Thank you for your support and readership here! That's what made this possible! <3

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aldnoah. Zero episode 7 and Terror in Resonance episode 6

Terror in Resonance episode six - Nine unclothed and the child in the machine

Terror in Resonance episode six was mostly build up and character development for Five. The police department is turning against Shibazaki, Nine and Twelve are walking into a trap, and Lisa is integrating herself into their makeshift family. The stakes have reorganized themselves now that SPHINX aren't the biggest bad guys in town. The stage is set for them and Shibazaki to be pulled together towards their common goal - the truth.

Nine has been stripped of a lot of his heroic delusions this episode. The first shot of him in this episode is him, unclothed, baring the wound he got trying to save lives during the last, nearly botched bombing. The line he's skirting by trying to force the police into investigating VON by bombing buildings but not actually killing anyone is almost nonexistent, and it probably won't survive intervention from his more ruthless old acquaintance, Five. Vestenet wrote a really great piece on the role that clothing plays in Terror in Resonance that informs a lot of my analysis now. I suggest that you read it. It expands on what I was saying about the role of glasses in the previous episode.

As a United States citizen, it's both really fun and surreal to watch foreign works with clearly anti-American sentiments. The new antagonists are from the FBI, a group that is in no way associated with hideous abuses of power over groups perceived as un-American. It seems that the PD's tendency towards hierarchical thinking has allowed the FBI to easily usurp power as an international or even American organization, whose interests are thus more important than Japan's. There's a proud history of anime criticizing American intervention in Japanese domestic terrorism, and I'm curious as to what this particular strain of it will end up saying. So far it seems to be a combination of Penguindrum's message about how societal disenfranchisement leads people to act out violently and something like Patlabor 2's criticism of "unjust peace" and American intervention, but I'm not sure how those connect yet. Maybe it's that the United States forces other countries to shoulder the burden of their defense efforts by using their populations to lure out threats to their interest? The US seems to have had a role in VON, so maybe they abused disenfranchised Japanese children in order to create human weapons?

(To those who don't know, the end of WWII impacted Japan much more than the United States. I won't go into too much detail, but basically in addition to all of the US insurgency efforts over the past few decades they've had military bases in Japan since the end of the Second World War. Article 9 of the Japanese constitution, the one that doesn't allow them to maintain a standing army, was also a US mandate.)

This episode characterizes Five as someone who has accepted her exploitation and uses it as a source of relative power. She doesn't take pleasure from her victories, but rather from other people's losses. Although she calls attention through her sense of dress and commandeering attitude, the fact that she is not in control of the situation never escapes her. The police and her handlers still look down on her, like an object. I'm interested to see if there's more to her than the insanity Nine and Twelve attribute to her. She seems to have had and a connection with them in the past. At one point Lisa, who couldn't be any more different from what we've seen of Five, is described as a replacement for her in their dynamic. Is she really an individual complacent in the system or is her victimization deeper than that?

Afterthoughts

I'm having trouble coming up with new things to say about Twelve and Lisa every week. They're adorable and I love them. That's about it. Continue on this path, show.

This episode at least had some top-notch engrish. "You've got to be kidding me."

I really like the set design in these two shots. The police chief sits in front of some naturalistic, decorative china while FBI Agent Clarence has his back turned towards what seems like a foreboding computer screen.

More chain-link fence imagery. It's their point of connection.

Damn. What are you suggesting here, Nine?

Aldnoah. Zero episode seven - A turning point, maybe?

Stuff finally came to a head in this last Aldnoah. Zero. It turns out that I was right! Tanegashima was being occupied for a reason - it contains the enemy Kataphrackt and battleship captured by Marito's company 15 years ago. This is a game changer in a show that has really, really needed one for quite some time. Slaine and Inaho are finally on the same side, if only momentarily, which enables the Terran Defense Force to get out of yet another altercation with a Martian general intact.

Inaho is an odd exception in Urobuchi's pattern of writing emotionless characters. Emotionlessness is usually the ultimate evil in Urobuchi's conception of the world. He associates it with ruthlessness, nihilism, utilitarianism - the complete absence of the traits that make humanity admirable. Madoka had Kyubey, Fate/Zero had Kiritsugu Emiya and Kotomine Kirei, and Psycho-Pass had Shogo Makishima. Inaho is different in that he's the first character for whom this is largely presented as a positive. Kyubey can't feel because he isn't human, and he craves control under the guise of a benevolent but utilitarian to save the universe. Kotomine Kirei can't access his emotions because of his strict upbringing as a religious assassin, so he craves validation under the guise of understanding. Makishima is a naturally cold person who, lacking a place in society, uses fermenting revolution as an excuse for companionship.

Inaho might be an exception to all this. He's most like Kiritsugu in that he has the extraordinary ability to cut off his emotions and focus when there's something he needs to accomplish, but he hasn't fallen into any of Kiritsugu's pratfalls. Unlike Kiritsugu, he seems fine at connecting with other people and hasn't had to sacrifice human lives to accomplish his goals. The worst thing he's done is admit to using the Princess as a pawn and dump Slaine's sorry ass in the ocean when he doesn't like that idea. That's cold, but it's nowhere near as cold as Kiritsugu killing his father and mother figure, or even Slaine straight-up executing Trillram after he reveals that the Orbital Knights orchestrated the Princess's assassination. Inaho is also situated in an odd place within the narrative for the emotionless character in an Urobuchi show. While Kyubey, Kotomine Kirei, and Makishima are invisible walls that the protagonists butt heads against, Inaho is the good guys' active player. Although Kiritsugu is the main character of Fate/Zero, his actions are much more ambiguous than Inaho's from the very beginning, and his presence was watered down by the cast of thousands. Inaho is much more clearly the central player of one of Aldnoah. Zero's two or three factions, whereas Kiritsugu was at the center of one out of ten. It's unclear so far whether the Booch is trying something different with Inaho or whether this is just a sign of Aldnoah. Zero being fauxrobuchi. I'm hoping for the former, but this show's on a short leash.

One good thing that I do have to say is that the direction has been steadily improving. This show's director, Ei Aoki, previously collaborated with Urobuchi on Fate/Zero. While Fate/Zero isn't an ugly show, its direction is a definite weak spot. Aoki's fine with action scenes, but I don't think he knows how to make conversations all that engaging, which is an issue because Fate/Zero mostly consists of long-winded digressions on moral issues. Compare this to Madoka Magica or the Monogatari series (both directed by Akiyuki Shinbo, a previous Urobuchi collaborator), which have similar amounts of dialogue-based scenes but manage to make them dynamic, captivating. I think that Aoki is getting better at making use of both color and environments. Fate/Zero tended to use setpieces surrounding one huge empty space where all the shit would go down, while environments in Aldnoah. Zero tend to be utilized more by the characters or to convey information about emotional states. He's also started mixing up the colors within scenes a bit. While in Fate/Zero entire episodes can be pinpointed by the color that dominates them - the initial confrontation between Saber and Lancer is dark blue, Kotomine Kirei's basement is shitstain yellow - that's lessened a bit here. Combinations of hues now define episodes more, which makes the direction stand out in a positive way. If only the writing would catch up.

Afterthoughts

I like how Femianne named all of her flying destructo-fists and gets angry when they're destroyed. It's a cute detail.

Coolest part of the episode - that one scene where the directing conveyed what'd be like to be a civilian right next to all of that military action.

14 notes

·

View notes

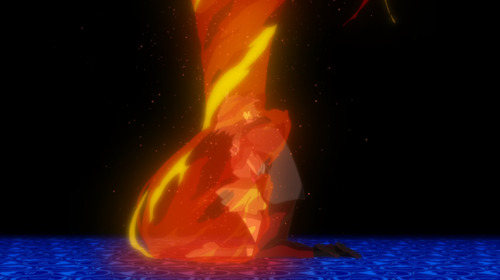

Photo

From Night on the Galactic Railroad (1985), a weird, dark, cool adaptation of Kenji Miyazawa's novella.

940 notes

·

View notes

Text

Night on the Galactic Railroad, or the Apple, the Scorpion, and the Stars

From a series on Mawaru Penguindrum’s literary influences.

This place is cursed with spoilers.

Night on the Galactic Railroad (1927) is a novella by Kenji Miyazawa. It takes place in the fictional fairy tale country resembling Italy. There, on the night of the annual Centuarus Festival, two boys, Giovanni and Campanella, are whisked away on the titular Galactic Railroad to tour the heavens. While on this journey, they confront the nature of human connection, transience, and sacrifice. At the end of the story, Giovanni and Campanella part ways. Campanella was on the train because he drowned during the festival and was on his way to the afterlife, while Giovanni, still alive, was allowed on the journey with his friend.

Mawaru Penguindrum specifically seems to be influenced by the 1985 anime adaptation directed by Gisaburo Sugii. It's a faithful adaptation, but it plays up the story's somber parts. The darkness at Penguindrum's core seems borrowed from this version of the story rather than the original. Shouma and Kanba resemble Giovanni and Campanella as realized in this version.

Giovanni (right) and Campanella (left) on the Galactic Railroad.

Like Giovanni, Shouma is associated with the color blue and has a sensitive, demure personality. Like Campanella, Kanba is associated with red and is determined, distant, but ultimately devoted to his friends. Unlike NotGR, however, Shouma and Kanba depart together at the end. It seems to me as if Ikuhara has dwelt on the sadness of Giovanni and Campanella's parting at the end of the original story and, in Penguindrum, created a version where they could be together in the end. Penguindrum also explicitly references Kenji Miyazawa in its first and last scenes. Near the beginning of the first episode, a pair of children are walking out side the Takakura's home discussing what the apple means in NotGR. You can tell because they mention Campanella and someone named Kenji - the novella's author Kenji Miyazawa. This exact conversation repeats in the final moments of the last episode, but this time the boys have Shouma and Kanba's hair colors and the audience follows them as they keep walking into the stars.

THE SCORPION FIRE

Night on the Galactic Railroad also contains the explanation for that scorpion metaphor! A lot of people get stuck on this - Kanba is referred to as a scorpion several times throughout Penguindrum, and allusions are made to him burning up. This is actually direct reference to NotGR, where the story of the burning scorpion exists as a fable told to the main characters as they're on the train. You can see it in this clip:

""My father told me its story: A long time ago in a field there lived a scorpion that ate other bugs by using its tale to catch them. Then one day he found himself cornered by a weasel. Fearing for his life, he ran but could not escape it. Suddenly, he fell into a well and, unable to climb out, began to drown. He started to pray then, saying:

"'Oh, God. How many lives have I stolen to survive? Yet when it came my turn to be eaten by the weasel, I selfishly ran away. And for what? What a waste my life has been! If only I'd let the weasel eat me, I could have helped him live another day. God, please hear my prayer. Even if my life has been meaningless, let my death be of help to others. Burn my body so that it may become a beacon, to light the way for others as they search for true happiness.'

"The scorpion's prayer was answered, and his body became a beautiful crimson flame that shot up into the night sky. There he burns to this day. My father was telling the truth…"

From Night on the Galactic Railroad, translation by Julianne Neville.

The fable of the scorpion fire is about sacrifice. The scorpion, who lived his life as a foul predator, faces something more powerful than him - the inevitability of death - and regrets that, after a life of heedless consumption, he couldn't die in a way that aided the proliferation of life. The gods hear his prayers and set him on fire, turning him into the red star Antares, heart of the constellation scorpio, whose light aids life.

From episode 12. Kanba offers his life to the Princess of the Crystal's in exchange for Himari's and, due to the purity of his sacrifice, it is acceptable. Unlike later on in the series, here Kanba is exhibiting the true nature of sacrifice.

This fable gives insight into Kanba's motivations but not his actions. While the scorpion discovers his kinship with all life, Kanba is rushing headlong towards a sacrifice that nobody wants but him. Kanba views himself as a predator and wants his final, massive act of predation - the terrorist attack - to lead to some concrete good: extending Himari's life. His role as a man of action rather than a man of reflection (Shouma) binds him to Sanetoshi's will, which offers a convenient means of achieving his goal. But those outs don't exist in the real world, and these justifications can't be made ahead of time. Shouma knew this and Kanba should have known. Maybe that's why it's Shouma, the brother with a more intuitive understanding of sacrifice, who bursts into flames and not Kanba, who fades away. Kanba's identification with the scorpion represents misguided, emotionally selfish sacrifice - egoism - while Shouma, Ringo, and Momoka's association with the purer flame represents true, transcendent sacrifice.

From episode 24. Ringo casting the spell ("Let's share the fruit of fate!") and subjecting herself to the scorpion fire.

THE APPLE

There's a scene late in the novella where Giovanni and Campanella encounter some people who died on the Titanic. The trio consists of two children and their governor, who allowed them all to die to make room for more people on the lifeboat. These people tell Giovanni and Campanella about the scorpion fire, and this is also where apples come into play. A lighthouse keeper, traveling down the train, gives them some apples, which they disperse amongst themselves. The film actually makes it so that the flocks of birds that they see flying outside the windows turn into the apples - something that wasn't present in the original story. Apples as a metaphor for live sacrificing itself for the sustenance of more life seems to originate here, since that wasn't tied to the apples in the original story.

Christianity, apples symbolize knowledge and defilement. NotGR however, reclaims that image. Here, they represent people understanding their limitations as individuals and accepting community - and the necessity of making sacrifices for humanity's greater good - as a way to make up for their flaws. NotGR stresses over and over again that people value humanity or some abstract conception of "life" over themselves, and that this path leads to profound spiritual contentment. Penguindrum borrows this idea and the apple symbolism wholeheartedly, but emphasizes valuing one's interpersonal relationships as a proxy for loving all life.

From episode 20. Himari reinterprets the biblical Fall of Man as a good thing because it allowed humanity to experience connection and joy, however transient, alongside pain.

One of the biggest mysteries left in Penguindrum to me is what Kanba sharing the apple with Shouma represents. I know what happened between Shouma/Himari and Kanba/Himari. Shouma brought the abandoned Himari into his family and Himari brought Kanba into the family after his father's death. But what happened between Kanba and Shouma? How did Kanba have to save Shouma by sharing his fruit of fate? It's left purely abstract - Shouma and Kanba were starving, Kanba shared his fruit, and both were saved by the gesture. Maybe Kanba helped Shouma by being assertive and dedicated in situations where he wasn't naturally inclined towards that? Like Giovanni and Campanella, Kanba and Shouma have complementary existences. Giovanni couldn't exist on his own without adopting some of Campanella's traits, while Kanba and Shouma, although they acquiesce to each other a bit, ultimately reaffirm their paired existence. I opened this up to discussion with some people on twitter and Bryan Baxter suggested that the two boxes Kanba and Shouma are in during episodes 23 and 24 are their mothers' wombs, and that by sharing the fruit of fate they became spiritual twins (they were born on the same day). Yoni Linder suggested that Kanba helped Shouma survive the KIGA group's brainwashing when they were children. It is odd that Shouma, the Takakura actually born into the cult, is the one least susceptible to it.

The idea that there's something beyond what we consider life is central to NotGR, which uses Christian imagery and often seems overtly Christian in its themes. Kenji Miyazawa was a devout practitioner of Nichiren Buddhism, but like many Japanese people his life was saturated with Christian imagery and scraps of biblical scripture. Christianity exists and is portrayed positively in NotGR, but neither Giovanni nor Campanella seem to be practitioners. When Giovanni and the children get into an argument over whose god is "real," the tutor reconciles them by raising the possibility that their gods are one and the same and reminding them that the point of religion is true faith in what you believe. NotGR is thus a neutral but positive synthesis of Christian and Buddhist images towards a more generically humanist message.

""And who says he's the real God? I'll be he's a fake!"

"How would you know? Maybe the God you believe in is the fake."

"No! He's the real one!"

"Then tell me, what kind of God is your God?" asked the young man with a gentle smile.

"Well… to be honest, I'm not quite sure… but I do know he is the one true God," Giovanni replied.

"Of course he is. There's only one true God."

"And my God is that one!"

"I agree. I can only pray that the two of you are seeing us off before that true God now," the young man said, clasping his hands together. Kaoru also clasped her hands together.

Everyone was sad to be parting, and Giovanni was about to burst into tears."

From Night on the Galactic Railroad, translation by Julianne Neville.

Over time, it becomes clearer and clearer that one of the railroad's purposes is to deliver people to the afterlife, two of which are represented by giant glowing crosses. "Dying for love" thus means something more concrete in NotGR than it does in Penguindrum. There's an actual reward for doing it - entrance into heaven. The same isn't true in Penguindrum, where the existence of an afterlife is much more abstract. Sanetoshi and Momoka were humans with some supernatural powers who died and became ghosts, but that form of afterlife seems much more a curse than a reward. In the last episode, Momoka vanishes from this world for good through some sort of opening, but exactly where she goes is unknown. Penguindrum's final shot is of Shouma and Kanba, having died for love, walking into the stars. While characters do allude to god, the show as a whole seems nonreligious, more concerned with taking the aspects of stories it deems meaningful and applying them towards a new, secular humanist message. Here, god is synonymous with fate, chance, or destiny - the circumstances outside human control that one is subjected to and dictate life. So what is Kenji saying? I think he's saying that humanity's survival up to this point has been due to our ability to love each other, to willingly sacrifice for the greater good, and that this is the foundation for human existence. That's where everything really begins.

#penguinlit#Kenji Miyazawa#mawaru penguindrum#penguindrum#kunihiko ikuhara#night on the galactic railroad

810 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Like I said, the apple is the universe itself! A tiny universe in the palm of your hand. It's what connects this world to the other world. The world Campanella and the other passengers are heading to."

"The other world? But everything is over when you're dead."

"The apple is also a reward for those chosen to die for love."

"What does that have anything to do with an apple? I'm not following you at all."

"What Kenji was trying to say is that's actually where everything begins!""

From episode one. Compare with these from episode 24:

182 notes

·

View notes

Link

Damn I’m sorry. That’s shitty of me. I’ll be more careful about that in the future.

Should I edit the post or leave this response up to shed light on my mistake?

A bit late, but here on my thoughts on the recent international hit Snowpiercer.

Snowpiercer starts out seeming like a serious action film with some subversive elements but then it turns into a worse version of The Hunger Games on a train. There were three big...

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

In terms of Marxist analysis, I'm interested in the subject but don't want to judge it until I've read some, which I will be doing this upcoming semester in a dedicated class.

I also have a lot of delicate personal feelings regarding communism because I was raised by Cuban exiles and my father is an adult immigrant from the former USSR. Ineed to tread delicately around the subject for my own health.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thank you for the great response! I understand the ending, just thought the final moments were conveyed so poorly that it took me out of the film. Snowpiercer is obsessed with showing how the train works while demanding huge leaps in logic for important thematic moments.

This (and the other review the OP linked to in another post) are interesting evaluations of the film for people interested in the hardcore Marxist perspective.

Snowpiercer doesn't have it both ways

A bit late, but here on my thoughts on the recent international hit Snowpiercer.

Snowpiercer starts out seeming like a serious action film with some subversive elements but then it turns into a worse version of The Hunger Games on a train. There were three big things wrongs with Snowpiercer: the tone, the pacing, and the conceit. There are also two ways to experience Snowpiercer, as an action film or a societal critique. It fails as an action film because there isn’t much action in it. It fails as a critique because it’s badly presented and doesn’t have much of a message besides “capitalism is bad.” This message is somehow both overpowering and half-baked. It’s probably why Snowpiercer fails as an action film - the sequences at the beginning and middle of the film are thrilling, but then they they’re replaced endless explanations of how train society works by mugging caricatures of humanity that completely waste the first half’s propulsive energy.

I understand that Snowpiercer is supposed to be a revolutionary call for the overthrow of capitalism, I just don’t think it succeeds at this. I get it: the train represents capitalist society. Society is a progression of classes, with the lower class containing the most people but the fewest resources, while the upper class has the fewest people but most of the resources. In the Society Train, the poor people literally live in the back and are not allowed to go up to the front, where the rich people live and rave and wade in foot-deep baby pools. The train runs around in circles and requires regular purges of excess population to stay running. Growth is a lie. Underclass POC children are literally used as components of the machine and disposed of when they wear out. Its a simple message - capitalism is bad and needs to be destroyed, and while I don’t necessarily disagree with this message, I’m a bit over works that call for all-out change without thoroughly examining the massively complicated issue of “what is wrong with our society? How do we overthrow humanity without reducing humanity to a worse situation, or outright extinction?” Snowpiercer’s ending implies that humanity’s extinction is preferable to life on the train, and I don’t agree with that. I’m not even sure that it was trying to say that - it seemed to be implying an Adam and Eve situation with the survival of the two children, but that final shot tells me that they were eaten by that goddamn polar bear. I’m usually not this much of a stickler for detail over thematic intent in film, but it couldn’t show them somewhere that wasn’t the top of a frozen mountaintop, staring down a deadly predator?

Snowpiercer also shares many of The Hunger Games’ issues in its portrayal of the upper class, most notably the fact that wealth is coded feminine. In contrast to reality, this film’s image of the oppressed class is largely white and male. Of the seven rebels with speaking roles, there are four white men, one Chinese man, one Chinese woman, and one Black woman. The black woman joins the fight for the stereotypical reason of reclaiming her child, who has been stolen by the elite, and dies unceremoniously before ever accomplishing that. The Chinese man is his own agent working coercively with the revolution and is portrayed as a buffoon for most of the film, while the Chinese woman is his daughter and generally serves as an extension of his character. There are several more POC rebels who participate in action scenes but die off without having any lines. A white man is the lead, of course. He’s also mentored by a white man, raised another white man as his son, and squares off against the white man who runs the train in the end, so this film doesn’t challenge that image of power. The sections of the film spent with the upper class, however, linger on people engaging feminine-coded behavior such as wearing luxurious clothes, makeup, and partying. Many more women are shown as part of the upper class than are ever shown in the lower class. It’s a wasted opportunity, and I’m angered that some critics would have the gall to call this work intersectional. It might have power in the director’s native South Korea, where it’s breaking theater attendance records, but in the United States, where you have to go to an independent theater to even see this film, I doubt many people are unfamiliar with the idea that CAPITALISM MIGHT BE BAD.

I really didn’t like this movie. I didn’t even like the parts of the film that most people praise, like the performances. I hardly noticed Chris Evans and wanted to punch Ed Harris’s supposedly seductive character the moment he got onscreen. This movie lost me early on and I spent the majority of its run time in a state of bafflement. Now if you want to watch some good Asian cinema with revolutionary themes, I’d recommend the works of Japanese director Kunihiko Ikuhara, particularly Revolutionary Girl Utena and Mawaru Penguindrum. Unlike Snowpiercer, these are complicated, intersectional, and ultimately successful works about people discarded by society taking charge of their own lives.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snowpiercer doesn't have it both ways

A bit late, but here on my thoughts on the recent international hit Snowpiercer.

Snowpiercer starts out seeming like a serious action film with some subversive elements but then it turns into a worse version of The Hunger Games on a train. There were three big things wrongs with Snowpiercer: the tone, the pacing, and the conceit. There are also two ways to experience Snowpiercer, as an action film or a societal critique. It fails as an action film because there isn't much action in it. It fails as a critique because it's badly presented and doesn't have much of a message besides "capitalism is bad." This message is somehow both overpowering and half-baked. It's probably why Snowpiercer fails as an action film - the sequences at the beginning and middle of the film are thrilling, but then they they're replaced endless explanations of how train society works by mugging caricatures of humanity that completely waste the first half's propulsive energy.

I understand that Snowpiercer is supposed to be a revolutionary call for the overthrow of capitalism, I just don't think it succeeds at this. I get it: the train represents capitalist society. Society is a progression of classes, with the lower class containing the most people but the fewest resources, while the upper class has the fewest people but most of the resources. In the Society Train, the poor people literally live in the back and are not allowed to go up to the front, where the rich people live and rave and wade in foot-deep baby pools. The train runs around in circles and requires regular purges of excess population to stay running. Growth is a lie. Underclass POC children are literally used as components of the machine and disposed of when they wear out. Its a simple message - capitalism is bad and needs to be destroyed, and while I don't necessarily disagree with this message, I'm a bit over works that call for all-out change without thoroughly examining the massively complicated issue of "what is wrong with our society? How do we overthrow humanity without reducing humanity to a worse situation, or outright extinction?" Snowpiercer's ending implies that humanity's extinction is preferable to life on the train, and I don't agree with that. I'm not even sure that it was trying to say that - it seemed to be implying an Adam and Eve situation with the survival of the two children, but that final shot tells me that they were eaten by that goddamn polar bear. I'm usually not this much of a stickler for detail over thematic intent in film, but it couldn't show them somewhere that wasn't the top of a frozen mountaintop, staring down a deadly predator?

Snowpiercer also shares many of The Hunger Games’ issues in its portrayal of the upper class, most notably the fact that wealth is coded feminine. In contrast to reality, this film's image of the oppressed class is largely white and male. Of the seven rebels with speaking roles, there are four white men, one Chinese Korean man, one Chinese Korean woman, and one Black woman. The black woman joins the fight for the stereotypical reason of reclaiming her child, who has been stolen by the elite, and dies unceremoniously before ever accomplishing that. The Chinese Korean man is his own agent working coercively with the revolution and is portrayed as a buffoon for most of the film, while the Chinese Korean woman is his daughter and generally serves as an extension of his character. Edit: I have been informed that Song Kang-ho and Go Ah-sung's characters are Korean, not Chinese. I'm very sorry for this mistake and will try not to do it again. Thank you to bfals for pointing this out. There are several more POC rebels who participate in action scenes but die off without having any lines. A white man is the lead, of course. He's also mentored by a white man, raised another white man as his son, and squares off against the white man who runs the train in the end, so this film doesn't challenge that image of power. The sections of the film spent with the upper class, however, linger on people engaging feminine-coded behavior such as wearing luxurious clothes, makeup, and partying. Many more women are shown as part of the upper class than are ever shown in the lower class. It's a wasted opportunity, and I'm angered that some critics would have the gall to call this work intersectional. It might have power in the director's native South Korea, where it's breaking theater attendance records, but in the United States, where you have to go to an independent theater to even see this film, I doubt many people are unfamiliar with the idea that CAPITALISM MIGHT BE BAD.

I really didn't like this movie. I didn't even like the parts of the film that most people praise, like the performances. I hardly noticed Chris Evans and wanted to punch Ed Harris's supposedly seductive character the moment he got onscreen. This movie lost me early on and I spent the majority of its run time in a state of bafflement. Now if you want to watch some good Asian cinema with revolutionary themes, I'd recommend the works of Japanese director Kunihiko Ikuhara, particularly Revolutionary Girl Utena and Mawaru Penguindrum. Unlike Snowpiercer, these are complicated, intersectional, and ultimately successful works about people discarded by society taking charge of their own lives.

14 notes

·

View notes