ANY OF THEM is an online presence of author and critic Aaron Peck. For more information, please see my website: http://aaronpeck.ca Or contact me at the following email address: contactaaronpeck (at) gmail (dot) com

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

0 notes

Link

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Text

My Year in Writing 2019

Taking a cue from last year’s list, I’m posting links to a few pieces I wrote in 2019.

The year began with a very short piece on W. G. Sebald’s Austerlitz for Frieze magazine, in which I describe buying an ARC at a used bookstore a month before its publishing date: https://frieze.com/article/aaron-peck-wg-sebalds-austerlitz

After that I wrote a piece about the fascinating Canadian poet Sylvia Legris for Music & Literature: https://www.musicandliterature.org/excerpts/2019/3/27/the-wit-of-their-strange-appearance

Then, as Notre Dame burned, I was walking down to the river to witness the conflagration when I received a text message from one of my editors at Frieze asking me to cover it. I wrote it the next morning in two hours: https://frieze.com/article/notre-dame-fire-burning-paris

A bit later, I had the immense pleasure of writing about one of my favourite writers of my Canadian generation, Souvankham Thammavongsa, for Music & Literature. I’ve know Sou since 2003, even edited a small manuscript of hers in 2006, so it was a wonderful to spend some time with her new collection of poetry, Cluster: https://www.musicandliterature.org/reviews/2019/5/26/souvankham-thammavongsas-cluster

One of my more research-intensive pieces of the year was a review for the New York Review of Books Daily of “The Black Model,” an exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay, which explored the lives of the black models who appear throughout nineteenth and twentieth century French painting. It was one of the best exhibitions I saw this year: https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2019/06/22/reframing-the-black-model-at-the-musee-dorsay/

Another piece I really enjoyed writing was on some of the beguiling news stories from Belgium for The Halloween Review, a one-off online-only magazine, with contributions from Lydia Davis, Sheila Heti, Lynne Tillman, Jana Prikryl, Naben Ruthnum, Joni Murphy, Michael LaPointe, and many others: http://thehalloweenreview.com/curfew.html

The biggest commission I had this year was a profile on the artist Jeff Wall for Walrus magazine, in which I explored some of his most recent work, specifically a new photograph-of-a-painting entitled Recovery (which I like quite a bit): https://thewalrus.ca/one-photographers-artistic-encounters-with-the-selfie-generation/

And finally the year ended with a review of a new collection of previously unpublished material by Marcel Proust for Frieze magazine: https://frieze.com/article/new-collection-prousts-writings-uncovers-origins-his-complex-desires

Well, that’s it for now!

0 notes

Photo

My translation of Pauvre Belgique by Charles Baudelaire. A strange project, as I have no intention to publish it (although it is funneling into a different one). It is Baudelaire’s 150 pages of notes for a unfinished polemic against Belgium. A strange and troublesome text. Difficult to get through -- nasty, repetitive, boring, angry, yet hilarious. I started it sometime last year -- in, I think, September. Put it a way for a while and only got back to it a few months ago. What a bizarre experience.

0 notes

Text

My Year in Writing 2018

My year in writing. For years now, on this nearly dead tumblr I’ve been compiling lists of favorite books of the year. I am more and more dissatisfied with Best Of lists, so instead I’m providing a series of links to works of criticism that I had published. Was a good year for writing, with a number of pieces I’m particularly proud of.

The year began with a piece on the French book illustrator Gus Bofa for The New York Review Daily. Bofa is often seen as a precursor to Franco-Belgian bande dessinée, but he is equally as fascinating as a kind of modernist who broke boundaries between word and image:

https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2018/01/23/gus-bofas-low-life-art/

That was followed up by a review for frieze magazine of Badlands Unlimited’s recently published interview by the deceased American art critic Craig Owens. Owens’s approach to criticism feels particularly prophetic right now. In the 1980s, for example, he foresaw what would become known as “intersectionality”:

https://frieze.com/article/craig-owens-portrait-young-critic

Then was a piece on the American writer Harry Mathews for The White Review. His excellent posthumous novel, The Solitary Twin, was published by New Directions in the spring. Mathews was the first anglophone member of the Oulipo, a French avant-garde writing collective, which produces literary works by applying compositional constraints. Mathews was always secretive about how his constraints worked, and The Solitary Twin is no different in that regard. Even still, this is perhaps his most accessible and humane:

http://www.thewhitereview.org/reviews/harry-matthews-solitary-twin/

The same month saw my review of Belgian fashion designer Martin Margiela published in frieze magazine. Margiela had two concurrent exhibitions at Musée des Arts Decoratifs and Palais Galliera in Paris. His influence on culture at large since the 1990s is still underrated:

https://frieze.com/article/famed-fashion-designer-martin-margielas-career-firsts

Along with my piece on Gus Bofa, I was particularly proud of this strange article on the graphically violent political graffiti of Brussels, which I wrote for The Happy Reader:

https://www.thehappyreader.com/issue/11/

In Paris this summer, I saw a fantastic exhibition of the Japanese modernist painter Foujita at the musée Maillol, which I had the pleasure of writing about for The New York Review Daily. He is mostly associated with the School of Paris in 1920s Montparnasse. Foujita is having a bit of a moment right now, and I’m glad to have had the opportunity to write about him:

https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2018/05/27/foujita-imperial-japan-meets-bohemian-paris/

Finally, right as the year ended, I wrote about Two Step, Emma Ramadan and Chris Clarke’s translation of Olivier Salon and Jacques Jouet’s play, Pas de deux, for The Quarterly Conversation. I was particularly interested how this little Oulipian play could help me think about translation as a kind of friendship:

http://quarterlyconversation.com/two-step-a-boolean-comedrama-by-jacques-jouet-and-olivier-salon

Many thanks to the editors of all of the above. I have never had the pleasure of working with such an exceptionally talented gathering of people.

#craig owens#gus bofa#martin margiela#aaron peck#translation#foujita#harry mathews#oulipo#the happy reader#frieze magazine#the white review#new york review#the quarterly conversation

0 notes

Text

Vive les ramonages!

I love living in France. This morning, I completely forgot that the chimney sweeps (yes, this is still a thing here -- les ramoneurs) had booked an appointment to clean our fireplace. Really nice guys. They remembered me from last year -- that I was a writer, and an anglophone. We chatted. They gave me a bit of a French grammar lesson. One of them asked me if my French was improving. So I told them that, as a way of learning, I was translating Baudelaire. They both nodded with approval. I love that about this country. The workers who come by your house do their work, then chat about grammar, and finally approve of your choice of translating 19th century poets.

Speaking of, on Friday, I’ll be reading from those translations -- Baudelaire’s Pauvre Belgique, prose fragments about his hatred of living in Brussels. I, too, hated living in Belgium. The event is at the American University of Paris, at The Center for Writers and Translators. This Friday, 18:30. Come by, if you’re in Paris. You need to RSVP, and bring photo ID, but otherwise it’s open to the public.

https://www.aup.edu/news-events/event/2018-09-21/center-writers-translators-salon

0 notes

Text

Paul Klee, “Two Men Meet, Each Believing the Other to Be of Higher Rank,” 1903.

0 notes

Text

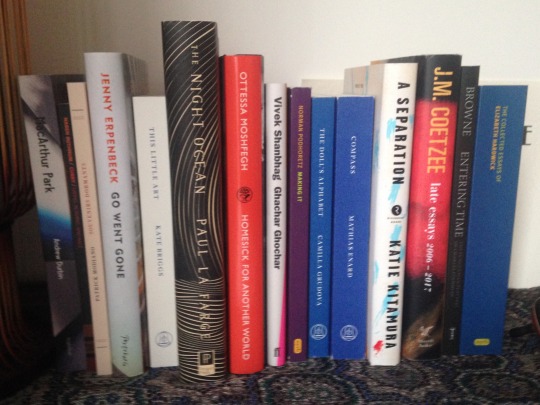

A Year in Reading: My Favourite Books Published in 2017

Mathias Enard, Compass (New Directions/Fitzcarraldo, 2017). Trans. Charlotte Mandell.

The insomniac thoughts and memories of Franz Ritter, an ethnomusicologist who specializes in how western classical music has been influenced by music of the east. Over the course of one night, he reflects on his life and work, particularly as it related to a woman he loved, another orientalist scholar whom he continuously encountered on field work throughout the Middle East. A fascinating meditation on the interpenetration of self and other, as well as a requiem for the places and cultures recently destroyed by civil war and the continued aftereffects of colonialism. Easily my favourite book of the year. I read it in French originally when it appeared in 2015, and Charlotte Mandell’s translation was excellent -- I rarely enjoy a translation of a book I’ve already read as much as I did this one.

Jenny Erpenbeck, Go, Went, Gone (New Directions/Portobello, 2017). Trans. Susan Bernofsky.

A recently retired classics professor becomes more and more involved in the plight and lives of recent migrants to Berlin. He also thinks back on his own life and history as an East German. The way the protagonist's experiences -- the whole swath of his East German historical tapestry -- were wax-printed onto his observations of the refugees made it global in a way that European novels rarely achieve, so often caught up in themselves, and only themselves. With this, Erpenbeck managed to conjure a way into the world that connected the twentieth century history of Europe with something more contemporary: its present, which is no longer only the purchase of Europeans.

Paul La Farge, The Night Ocean (Penguin, 2017).

A man goes missing not long after realizing that he had been conned into believing a manuscript detailing H. P. Lovecraft’s sex life with a younger man was authentic but then continues on a quixotic quest for the truth. I’m not even a Lovecraft fan, but this novel -- with its mise-en-abyme stories within stories within grifts within stories -- was unputdownable. It is as much about reading and fandom as it is about Lovecraft. About the way stories attempt to form our world into something more than a night ocean.

Ottessa Moshfegh, Homesick for Another World (Jonathan Cape, 2017).

A collection of stories by the author of Eileen. Drifters, failures, fuckups. Her prose is such a pleasure to read, its forensic exactitude.

Camilla Gurdova, The Doll’s Alphabet (Coach House/Coffee House/Fitzcarraldo, 2017).

I loved these strange parables. The ways she took her stories and sentences were continually unexpected. This book about transformations, women, and animals is so sui generis that it begs comparisons -- Sheila Heti, Marie Darrieussecq, Angela Carter, Marie de France, David Garnett -- if only to prove that none of them quite hold.

Vivek Shanbhag, Ghachar Gholchar (Faber, 2017). Trans. Srinath Perur.

A man recounting the story of his marriage over one evening after he discovers something unspeakable. The novel -- novella? -- is extremely short. But every piece of the story is exactly where it needs to be. In a way, its form reminds me of the best longer stories by Henry James.

Katie Kitamura, A Separation (Riverhead, 2017).

A woman goes to Greece to look for her estranged husband who has gone missing. Once there, she finds herself with more of a problem than she originally thought. I read this when it was released, and more than many other novels from the beginning of the year, its images have remained. I’ve heard it described as being somewhat like Javier Marias. I don’t think so. It’s doing something quite different. Although the narrator does have a penchant for observation, its style of storytelling is more controlled. Kitamura is also excellent with images, like those of a slightly aloof poet, whose images of a hot and arid Greek landscape have stayed with me.

Patrick Modiano, Souvenirs Dormants (Gallimard, 2017).

Thematically and stylistically, Modiano has nothing to prove, so this novel continues where his previous ones left off. A story about the way people from your past can reappear unexpectedly. It’s his first since winning the Nobel. Modiano is doing what Modiano is good at. That said, I would put it above Pour que tu ne te perds pas dans le quartier, for example. It’s not as good as Dans le cafe de la jeunese perdue or La place d’etoile, but it’s that’s not saying much. It’s still good. It also happens to be partially set a block away from my current apartment...

Naben Ruthnum, Curry: Eating, Reading, Race (Coach House, 2017).

The topic at heart of Curry is language -- how words are used, how they designate, market, and identify. The book attempts to address the ways in which writers of colour, in this case brown writers, relate to the signifiers associated with their so-called culture of origin. Ruthnum manages to address such complicated ideas about race and culture all the while coining a term to indicate a kind of book that white people seem to love seeing brown writers publish: currybooks. Ruthnum addresses the problems head on, considering his own Journey prize-winning story “Cinema Rex,” the first and only time he delved into his Mauritian heritage, as well as providing a literary assessment of South Asian diasporic writing, the pitfalls of an industry that seems to pigeonhole brown writers in a specific genre of literary novel. (Full disclosure: I’ve known Naben since he was three. Throughout the writing of Curry, I kept jokingly pestering him via email to include me in the book because I cook his mom’s dahl recipe weekly.)

J M Coetzee, Late Essays: 2006-2017 (Harvill Secker, 2017).

His three essays on Beckett are more than worth the price of admission alone. Of interest to me also were the essays on German literature -- those on Kleist, Walser, and Goethe. At his best, he is one of my favourite living writers, as both a novelist and critic; at their best, these essays did not disappoint.

Colin Browne, Entering Time: The Fungus Man Platters of Charles Edenshaw (Talon, 2016*).

Poet, filmmaker and critic Colin Browne’s essay Entering Time (about the “Fungus man” platters of nineteenth century Haida artist Charles Edenshaw) attempts wrestle with some of the tensions inherent within Canadian culture: the far too unspoken imbalance between its settler-colonial population with its indigenous one. The essay grapples with the dynamic of a white person engaging with the art of the North West coast without losing focus on its subject: the aesthetic marvels and legacy that are the work of Charles Edenshaw. It then proceeds to offer an incredibly convincing interpretation of these masterworks of Haida art.

*The colophon says 2016, but I don’t think it was available in Canadian bookstores until Jan. 2017.

Kate Briggs, This Little Art (Fitzcarraldo, 2017).

A meditation on Briggs’s translation of Roland Barthes, This Little Art becomes an essay on the art of translation, on the relationship between translators and authors, specifically women translators, as well as being about the late work of Roland Barthes. I remember reading Briggs’s translation of Barthes’s In Preparation of the Novel years ago when it was published, and it was such a pleasure to read this extended essay. Until this point, my favourite book on translation has been Rosemary Waldrop’s A Lavish Absence: Recalling and Rereading Edmund Jabés (Waldrop’s excellent memoir about translating, reading, and knowing the great poet). But I think This Little Art now takes the throne as my favourite book by a translator about the art of translating.

Norman Podhortez, Making It (New York Review of Books Classics, 2017).

I never thought I’d like something by one of the architects of the neocon movement, but so it goes. A friend gave this book to me after we discussed something that I was working on. Said she thought I’d enjoy it, and I did. It is a frank and bitter depiction of the New York intellectual scene that surrounded the Partisan Review. A fascinating document in twentieth century intellectual history. It’s also a compelling memoir in its own right. A must read for anyone interested in that generation of New York critics, but especially if you’re interested (as I am) in Clement Greenberg...

Andrew Durbin, MacCarthur Park (Nightwood, 2017).

A novel about a young writer who is writing a novel about the weather. Or so he says. It also is the novel that we, as readers, are reading. Upstate utopian colonies, artists, gay New York club life, hurricane Sandy, the Tom of Finland Foundation, failed attempts at transcendental meditation, the ebb and flow of romantic relationships, all fit into the story of a young man in New York. It’s a portrait of a place, and it’s also, I think, quite a perceptive meditation on names -- how meaning is projected onto something via its name. In that way, as well as in its form, it’s a very Proustian novel.

Elizabeth Hardwick, The Collected Essays of Elizabeth Hardwick (New York Review of Books Classics, 2017)

Although I’m not finished this, I’ve been savouring each essay. All 600 pages worth of them.

Special mention (aka shameless promotion)

Pierre Mac Orlan, Mademoiselle Bambù (Wakefield, 2017). Trans. Chris Clarke.

I can’t properly include this book because (a) it’s not released until December and (more importantly -- full disclosure -- b) I wrote the afterword for it (on the French illustrator Gus Bofa whose illustrations accompany Mac Orlan’s tale). Otherwise I would be calling it one of the great finds of the year. It still is. (But with that caveat of full disclosure.) A tale of early twentieth century espionage. Mac Orlan was once condescendingly referred to as “le Proust des pauvres,” which I think is a compliment in so many unintended ways. A writer who straddles the line between avant-garde modernism and various kinds of genre fiction (in the case of this novel, mystery and espionage), Mac Orlan deserves a far greater readership. Check it out: http://wakefieldpress.com/mac_orlan_bambu.html

0 notes

Text

Top Books 2016: A Year in Reading*

Books published for the first time in 2016 (in no particular order -- English, French, and translations)

Dodge Rose, Jack Cox (Dalkey Archive, 2016)

The story of how Jack Cox’s novel about inheritance and property laws in Australia (really it’s about way more than that too) was acquired by Dalkey Archive has become something of a legend. You know from the spare first sentence (“Then where from here.”) that Cox has an insanely elegant syntax; the one following is among the best I’ve read in years. It’s no surprise that this manuscript was picked out of the slush pile. Comparisons to Beckett are not hyperbole. This is not some kind of derivative third generation Gordon Lish acolyte whose turns of phrase beg to wow you. Maurice Blanchot talks about two different kinds of writers -- those who experience language as abundance or those who experience it as lack. Cox is in the first category -- you can’t achieve that kind of precision if you are struggling with your own lack of language.

Chanson Douce, Leïla Slimani (Gallimard, 2016)

My French is still a bit rough, so even though I can read, I question if I can judge the literary quality of books in French. Still, the last five pages of this Prix Goncourt winner were so engrossing that I felt compelled to reread them as soon as I finished the book -- not because I couldn’t understand them, but because they were so good. The story of a bourgeois family and the nanny they hire, Chanson Douce is about contemporary Paris and all of its socioeconomic disparities. I also like what it didn’t narrate, what it chose to leave unsaid.

In the Café of Lost Youth, Patrick Modiano, trans. Chris Clarke (New York Review of Books, 2016)

After I read In the Café, I also read it in French just to get a sense of how Clarke, whom I’ve known for years, translated it. (And I doubt I would have read the translation if I hadn’t known him.) Clarke manages to approximate Modiano’s tone and voice in English, as well as taking a few interesting liberties, which is difficult to do, with Modiano’s elements of noir, plus the spartan and surreal quality of the prose. There is a simplicity to Modiano’s prose that, in the wrong hands in English, comes off as corny. Clarke gets the tone right at times by making some unique changes of phrase.

The Noise of Time, Julian Barnes (Jonathan Cape, 2016/Knopf, 2016)

A new book by Julian Barnes. Do I need to say more? OK, I’ll say more: A new novel by Julian Barnes about Shostakovich. A book about the life of an artist who compromised his life just so that he could continue to make work under an oppressive regime. The book is in turns pathetic and heartbreaking. Barnes continues to be one of the best stylists in English. That clarity.

Le Cas Annunziato, Yan Gauchard (Les Editions de Minuit, 2016)

On a few occasions, I had to put the book down because I was laughing so hard. I loved this strange tale of a man who becomes trapped in an Italian museum (in a Fra Angelico room, nonetheless). Then it follows all of the resulting complications and fame. I also admired how the novel could switch between a comic register to serious political commentary. This is a book that I think I would like to translate; we’ll see.

Transit, Rachel Cusk (Jonathan Cape, 2016)

Second in her trilogy of novels that began with Outline, the mostly plotless observations of a narrator as she moves back to London, newly divorced, Transit sees Cusk continue to develop the style that made Outline so good.

Counternarratives, John Keene (Fitzcarraldo, 2016/New Directions, 2015)

A collection of fictional documents, accounts, stories, and monologues that retell the history of North and South America through the eyes and voices of black Americans, from early slavery in Brazil onward. From the formal ingenuity to the political acumen of Counternarratives, as well as the virtuosity of command of different styles, genres, and voices, I’ve never encountered a book like it before, even though I can see its precedents (Samuel R. Delany, for example). (Released by New Directions in 2015, but I read the Fitzcarraldo Edition, which was released in 2016, so I’m including it here.)

3 Summers, Lisa Robertson (Coach House Books, 2016)

These poems are the result of three summers lived in rural France. In some sense, they continue from Lisa R’s Magenta Soul Whip. With Robertson’s sumptuous and brilliant balance of vagueness and clarity, each book is also, in a sense, a reading diary. We continue to follow the speaker meander through a long study of the Epicurean poet Lucretius, Hannah Arendt, and others, as we also encounter the France of Robertson’s writing.

Le Materiau Humain, Rodrigo Rey Rosa, trad. Gersende Camenen (Gallimard, 2016)

It’s become a bit of a genre: the Latin American writer who writes a novel about accessing archival documents relating to war crimes or police brutality. And this is Rodrigo Rey Rosa’s contribution to it. When will this be translated into English? It needs to be. I’d put it in the top three or four Rodrigo Rey Rosa novels. I think that should say enough about that.

The Invisibility Cloak, Ge Fei, trans. Canaan Morse (New York Review of Books, 2016)

Comparisons to Murakami are irksome -- Ge Fei is a very different kind of writer, even if his protagonist is a music aficionado. Although I’ve never been to Beijing, this was the first book I’ve read that felt as if I were inside the city. He seems to know Beijing so well that he has no need to pontificate or rhapsodize. That said, is it possible to like a book and yet find its representations of gender and race disquieting? Translator Canaan Morse even mentioned this in a comment he made on Paper Republic before translating it. Mind you, there is not a single redeeming feature about any of the characters, all of whom are trying to get ahead in New China by swindling and scheming against everyone else, including other family members. So I have that significant caveat with recommending it. But, as a final aside, if you have ever wanted a literary novel with a joke about Jay Chou, here it is.

Eileen, Ottessa Moshfegh (Jonathan Cape, 2016/Penguin US, 2015)

This year, I read five of the six Man Booker nominees. I was particularly interested in the award this year because, even before the announcement of the short list, I had read four of them simply out of interest. Although I liked those four a great deal, and was thrilled with the winner, and would have been happy with others, Eileen was my favourite. It gave me nightmares. If a book does that, it’s done something right. (I read the Jonathan Cape edition when it came out in early 2016 in UK/Europe, so again, like Counternarratives, I’m including it in 2016, although Eileen was also a sensation in the US last year.)

The Surrender, Scott Esposito (Anomalous Press, 2016)

Originally, I was going to put this chapbook in an endnote, along with a shout out to Esposito’s excellent The Missing Books, Vol. 1 PDF, in a section dedicated to shorter books and pamphlets, but after thinking about how much I enjoyed this collection, I decided it needed its own complete entry. The fierce and passionate brilliance of these three essays that announce and explore Esposito’s desire to be a woman were among the best things I read this year. I loved his prose and voice.

Pond, Claire-Louise Bennett (Fitzcarraldo, 2015/Riverhead, 2016)

Certain parts of this book, “stories” if you will, wowed me -- I don’t say that lightly. To that end, though, it’s too bad that the Man Booker classified it as a “collection” because Pond has one continuous voice, a kind of fragmentary novel, and it should have at least been nominated.

The Quarry, Susan Howe (New Directions, 2015)

New Directions notes that this book was published in December 2015, but I couldn��t locate a copy to order until January. Howe’s prose shows us one possible path toward non-conformist thinking. Her essays on Wallace Stevens and Chris Marker were highlights for me. (It now rests in my small collection of essential works of criticism, along with Gertrude Stein, James Baldwin, Oscar Wilde, Jeff Wall, Hannah Arendt, Edward Said, Sir Thomas Browne, and Lynne Tillman.)

Sudden Death, Alvaro Enrigue (Riverhead, 2016)

A novel about tennis. And tennis shoes. And the violent history of colonialism. And Mexico. And the way in which the Americas were absorbed, via the violence of colonialism, into what we call the West. It’s about beheadings. And depictions of beheadings. The whole thing is structured around a tennis match between the Spanish poet Francisco de Quevedo and Caravaggio.

Reprints 2016 (not exactly “new” because they were previously published, or new collections of material previously published, I also wanted to include a few reprints)

The Complete Madame Realism and Other Stories, Lynne Tillman (Semiotex(e), 2016)

This is not exactly a reprint, but most of its material had been previously published in either Madame Realism Complex or This Is Not It, so I’m putting it in this category for those reasons. It collects some of Tillman’s writings on art, the Madame Realism pieces, the Paige Turner pieces, and finally the Translation Artist pieces (which I knew the least and which I was thrilled to read). For years, these stories have been incredibly influential on me, for the wit and irony of her voice, for the sharpness observation, and for how they show a contemporary way of mixing fiction and criticism. In Tillman’s prose, you can see her thinking -- the delightful jumps and shifts in thought as the reader follows her move from word to word, sentence to sentence.

A Fairly Good Time, Mavis Gallant (New York Review of Books, 2016)

A Canadian living in Brussels, I sometimes wonder if I’m a character in a Mavis Gallant story, so I reread her this year, including this reprint. Gallant writes with a generous irony: she lets her characters be, and she gives us enough distance from them to let us watch them be. That’s rarer than it sounds. She is a profoundly unconventional storyteller who manages to trick us into thinking her stories are conventional.

The Last Samurai, Helen Dewitt (New Directions, 2016)

A lot has been said about this book. Between it and Counternarratives, New Directions has published remarkable English-language books over the past year and a half. But what is there to say about The Last Samurai? I bought multiple copies. Enough said.

Books I didn’t get to but want to

Au peril de la mer by Dominique Fortier. (It was only on my second last day in Brussels that I discovered a bookstore that stocks littérature quebecois. I’d already overloaded my luggage for my month back in BC -- where not a single bookstore stocks Quebecois literature. I’ll read it next year.) Likewise, I’ve just picked up or intend to soon copies of Sam Wiebe’s Invisible Dead, Lauren Elkin’s Flanuese, and Meredith Quartermain’s U-Girl.

.

*I always try to read at least 100 books a year. I still have a two weeks left, and right now I’m at 97 -- safe to say I made my goal as I average two per week.

1 note

·

View note

Link

I’ll be giving an “Exhibition Reading” this Friday at the Witte de With in Rotterdam. If you happen to be in Rotterdam, or even in the Netherlands, stop by!

1 note

·

View note