Text

ART 225 Final Blog Post: Bob’s Java Jive

photo circa 1930

Located at 2102 South Tacoma Way, in Tacoma, Washington, this weird little building is not just a local attraction; it's on the National Park Service's National Register of Historic Places. Originally called the Coffee Pot Restaurant, it was designed and built by Otis G. Button, a veterinarian from Tacoma, in 1927, and opened in 1929. It was one of Tacoma's first prefabricated commercial buildings, with construction beginning on the tideflats and then individual sections moved to the property and bolted together on-site. It was one of a number of quirky object-shaped buildings erected alongside highways across the United States in the 1920s, intended to fascinate, both to draw new customers into the businesses housed within, and—in a time when speed limits were not standardised and signage was infrequent—to encourage drivers to slow down in order to get a better look at the sights. Unlike the three-story gas pump station next door or the giant lemon down the street, however, this one has stayed standing for almost a century at time of writing.

❗ BULLETIN: ROBBERY The Coffee Pot was robbed for the first time in November of 1936.

A change of ownership and a change of footprint took place in 1940 when Harold Elrod purchased the property and added a dance hall to the building. Elrod also obtained a liquor license and added a bar, though it was rumoured that the place had contained a speakeasy during the last years of Prohibition, so he may have just been legitimising a well-established tradition of drinking while adding a new tradition of dancing. With more space came larger crowds, and with a dancefloor came music. This kicked off the building's long history of musical gatherings.

❗ BULLETIN: ROBBERY It was robbed again in December 1945.

❗ BULLETIN: ROBBERY Robbed again in June of 1951. The Tacoma Public Library's notes on the location indicates that "yeggs loot[ed] safes here." Fun fact: "yeggs" was a slang term for a burglar or a safecracker and is thought to come from a bank robber who used the alias John Yegg. According to a source quoted by Ray City History Blog, John was "said to have been the first safe-cracker to use nitro-glycerine as an adjunct to the prosecution of his art," and subsequent crimes began to be referred to as being perpetrated by "yeggmen." A bit of broader and more language-based history mixed in with this local stuff!

In 1955, Bob Radonich purchased the building and renamed it the Java Jive. The name was suggested by Bob's wife Lylabell, who was inspired by a popular 1940 song of the same name performed by The Ink Spots. Lyrics from the song include, "I love coffee, I love tea; I love the java jive and it loves me!" Roadside America notes that Bob "made the Jive loosely Polynesian-themed," adding a "Jungle Room" and decorating with artefacts collected during his tour in India, Madagascar, and other places white Americans found exotic at that time. He also, in true fifties fashion, kept two chimpanzees named Java and Jive in a glass cage for customers to view. (The monkeys drew animal rights protests and other drama over the years, so Bob would eventually remove them from the establishment, sending them to "live with some friends.")

❗ BULLETIN: FIRE In April 1962, the fireplace caused a bigger fire than it was supposed to.

Until 1969, South Tacoma Way was known as highway 99, a main thoroughfare through the city, and "people would drive by and be lured in by the quirky shape of the building, then stay for a beer and the house band," as South Sound Magazine put it in their 2019 article about the place. Then interstate 5 was built, right over the Jive, and highway 99 became just another surface street. Bob's daughter Danette Staatz recalls how, after that, "there wasn’t the same kind of traffic — and it hurt business."

Despite the highway situation, by 1972, the Java Jive was world famous. According to Danielle, that year, "we were gonna paint the ceiling, and you would have thought that we were going to take a wrecking ball to the whole building. Everybody was so upset, we haven’t been able to paint the ceiling since.” Why was everyone so upset? Because the ceiling is "absolutely smothered with signatures from people all around the world who have come to visit," and is thus an important part of the building's story, to be preserved rather than painted over.

unknown date; source

photo from South Sound, circa approx 2019

...

♬♪ INTERLUDE: music, culture, legacy

The city of Tacoma is ground zero for grunge music. Grunge is inherently quite political; as Wikipedia puts it,

Grunge lyrics are typically dark, nihilistic, wretched, angst-filled and anguished, often addressing themes such as social alienation, self-doubt, abuse, assault, neglect, betrayal, social isolation/emotional isolation, psychological trauma and a desire for freedom. ... [they] contained "... explicit political messages and ... questioning about ... society and how it might be changed ...". ... The topics of grunge lyrics—homelessness, suicide, rape, "broken homes, drug addiction and self-loathing"— contrasted sharply to the glam metal lyrics of Poison, which described "life in the fast lane", partying and hedonism.

Peter Andrijeski writes a bar-crawling documentation blog at seattlebars.org. When he started the blog, he began with Bob's Java Jive, which he visited in 1982. (The chimpanzees were still there at the time, living in the back bar.) Pete nods to the Jive's history as a happening spot for the local music scene: "Before they made in big, The Wailers played there several times, and The Ventures played as basically the house band. Harold Lloyd, Clara Bow, and Bing Crosby are all said to have hung out there during the early years."

You may recognise The Ventures as the band who performed the Hawaii 5-0 theme song. They and the Fabulous Wailers, as well as the Sonics, were part of the evolution of rock 'n' roll into grunge; garage bands who became national darlings and blazed a trail that led to Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Alice in Chains, Mudhoney, Hole, the Smashing Pumpkins, the Foo Fighters...

Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk is a book comprised entirely of quotes from people who were at the centre of the mainstream explosion of punk music while it was happening, as they recall what it was like to live that maelstrom. While these people mostly came from the East Coast, their experiences are not entirely dissimilar from what was happening in the Pacific Northwest at that time. I present the following quotes without further commentary.

Ed Sanders: The problem with the hippes was that there developed a hostility within the counterculture itself, between those who had, like, the equivalent of a trust fund versus those who had to live by their wits. It's true, for instance, that blacks were somewhat resentful of the hippies by the Summer of Love, 1967, because their perception was that these kids were drawing paisley swirls on their Sam Flax writing pads, burning incense, and taking acid, but those kids could get out of there any time they wanted to. ... Whereas someone who was raised in a project on Columbia Street and was hanging out on the edge of Tompkins Square Park can't escape. ... They're trapped. So there developed another kind of lumpen hippie, who really came from an abused childhood—from parents that hated them, from parents that threw them out. ... And those kids fermented into a kind of hostile street person. Punk types.

Wayne Kramer: Any time you take a political stance, especially when you start throwing around violent political rhetoric, you're guaranteed a violent reaction from the powers that be. There was an attitude that prevailed in the Detroit area, amongst parents, teachers, policemen, and prosecutors: "When is somebody gonna do something about the [band Motor City 5]? We cannot allow them to say what they're saying!" We were telling people at our shows to smoke reefer, to burn their bras, to fuck in the streets—it wasn't just a matter of "Well, they were a little too wild for the record industry," which we were, but it went beyond that. Peace and love worked in the realm of the music business, but once you went beyond that, to revolution... that's bad.

Dennis Thompson: Nixon and the smart boys in the green room back in the brain trust sat down and said, "Here's the easiest way to handle this damn thing. Just take away their party favors." The government figured it out. It was obvious. "These people do pot and hash and psychedelics and then they get revolutionary, and they come up with all these new ideas like 'Hey, let's change this world. And let's eliminate these fascist politicians!' Well, the smartest thing to do is give them what's been in the ghettos for a long time because that's been working pretty good there." All of a sudden all you can find anywhere you go is heroin. It's cheap, and there it is. So heroin became the next drug of choice, mainly because you couldn't buy a kilo of pot to save your soul.

In 1980, the future singer and guitarist for Girl Trouble met at Bob’s Java Jive. They would go on to become local legends. Bon Von Wheelie, Girl Trouble’s drummer, reflected on being a punk in the 80s during an interview for Northwest Music Scene: "Since Tacoma was a working-class town the people here weren’t really open to anything new, including punk rock hairdos and clothing. It is almost unbelievable to think about that now but for some reason it made people so mad they’d go after anybody who dared to look even a little out of the norm (which was baggy flare jeans and feathered hair). Having tight pants and a short haircut could get you in a fight faster than anything."

Nirvana didn't play at Bob's Java Jive, but they did hang out there in the mid to late 80s, and it was at a different venue in Tacoma that they first performed under the name "Nirvana." A local legend is that the band asked Bob if they could play a set at the Jive, but Bob didn't like their sound and he turned them down. Nirvana's bassist Krist Novoselic says that's an urban myth.

Unlike Nirvana, Bobby Floyd Radonich, the owner's son, was a frequent performer at the Jive. He was said to be an incredibly talented piano player, and to have a thousand songs memorised to play any time a customer made a request. The Tacoma News Tribune also wrote an article in 1983 about Bobby Floyd's presence at the piano bench, saying in the headline that the "Java Jive comes alive when [he] plays." Pete said on his bar crawling blog that on the night he was there, "Maestro" Bobby Floyd "seemed to play mostly 70s television themes, mixed in with Beatles covers and local high school fight songs." Pete called the bar and his experience at it "epic."

...

photo of the Jive’s menu from 1990, shared on their facebook page

The 1990 film “I Love You To Death” was filmed entirely in Tacoma, and features a scene inside Bob's Java Jive. Keanu Reeves plays alongside William Hurt as pothead cousins and would-be hitmen who are hired to kill a cheating husband; the deal is struck at a table in the Java Jive. South Sound Magazine notes, "You can play pool at the same pool table that Reeves did. He [allegedly] offered to buy the coffee pot building for $1 million and move it to Hawaii. [Bob] turned the offer down." (This urban myth may have been sparked by the fact that Bob later put the Java Jive up for sale for $1 million, despite the property and building being worth much less at the time. There were no takers, so he kept the place.) The Java Jive was also featured in “Say Anything” and “Three Fugitives” the year before, and a decade later it would appear in “Ten Things I Hate About You.”

By 1995, Bob was in his late seventies and health was failing, so his daughter Danette took over the Jive.

❗ BULLETIN: FIRE Another fire in April of 1996 caused some amount of damage and caused the Java Jive to be shut down for a time.

❗ BULLETIN: ... wait never mind In 1998, there was a fire in the apartment complex behind the Jive, but the building itself escaped the blaze this time! Whew!

In July of 1999, Teddy Haggarty and Dan Richholt painted the above mural.

❗ BULLETIN: FINANCIAL TROUBLES In July of 2002, Danette spoke to the Tacoma Daily Index about the financial struggles she and her husband were facing due to lack of patronage. She promoted the event they were organising called The Big Hoopla to try to raise funds to keep the place open, with "dancers, live music, a juke box, pool, pinball and darts, as well as hot dogs and pop." Danette did not end up losing the Jive that year, probably in large part due to the event and the news coverage reminding Tacomans about their quirky little landmark and bringing in funding both from the event and from the likely boost in general patronage. Later that year, Bob Radonich died at 83 years old, with the famous coffee pot building still in the family.

2011 Yelp review: "This is the last Grit City hangout that hasn't been gutted and made into a fancy hangout for all the new transplant yuppies. Great vintage atmosphere and music venue. No hard booze here folks, just straight up beer and wine. Worth the visit."

2013 Yelp review: "the java jive is the most tacoma place in tacoma. a landmark, a tradition, and practically all that remains of our cultural past. built as a dine & dance joint in the 20s, then morphed into a rock club for the nascent garage/punk scene in the early 60s (think the sonics and the wailers), this roadside attraction is shaped like a giant coffee pot and like alice's wonderland, holds a mysterious variety of spaces inside. come here for a cheap pitcher of coors and a "jungle burger": a basic frisko freeze-style cheeseburger that's absolutely tasty and cooked to order. karaoke most nights, and occasional live music with a dance floor. just a great hang."

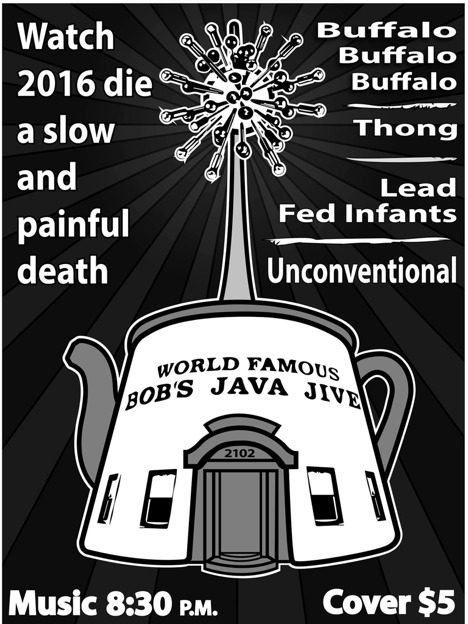

couple of my favourite show posters from facebook, circa 2014

In 2016 Huck Magazine added a video called Misfit City to their Huck Across America series on YouTube. This installment focussed on the “Grit City” music scene, with a huge showcasing of inclusive punkiness, and featuring a familiar little coffee pot shaped venue. In it, Hozen member Hozi says, "Tacoma is a misfit city, you know... I think that a lot of people feel comfortable to be themselves here in a way that you wouldn't necessarily feel in Seattle or Olympia because those places have so much of an identity. Here, you just... are who you are."

2016 show posters:

(2016 was recognised on the facebook page as a "shitty year")

The Jive has an overall rating of 4.5 stars on Yelp (as of December 2022). A lot of the naysayers seem to be disappointed that the coffee pot building was not a coffee shop (including one tourist who pulled over to take photos and then upon seeing the hand-scrawled sign on the front door decided not to go inside... but still left a three-star review based on their vague disappointment). Or that the dive bar atmosphere was not for them, to which I say: don't judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree. There are, however, quite a few comments about the state of the place around 2008–2015, with a handful of "this place used to be better" sentiments from people who had fond memories but seemed upset at the state of the place around that time. Luckily, the owners have done major renovations since then!

In 2019 they made a slew of announcements on facebook: they had installed a new karaoke sound system, acquired new arcade games ("a new dart machine that works!" and a new pinball machine), had the pool tables and the game area's carpet redone, bought a pretzel oven and hot dog steamer, installed security cameras for the first time to surveil the parking lot and surrounding area. Later that year, they got their wn library card! The Tacoma Public Library printed special edition library cards—a batch of only 3000—featuring the coffee pot building in its youth, before it had the colourful paint job and additional structure.

By this time, even non-natives were charmed by the place!

2019 Yelp review from a Kent resident: "I was very pleasantly surprised with how much I enjoy this place. Great karaoke, awesome people, wonderful atmosphere. I feel like this is a place where everyone is welcome and accepted which means a whole lot to me. I will most definitely be back and would absolutely recommend this spot to my friends!"

mural at the railroad bridge at 66th and south tacoma way, taken in 2019

❗ BULLETIN: GLOBAL PANDEMIC In March of 2020, the world stopped for a bit.

Renovations continued after the lockdowns. In June 2021 the exterior was repainted by Honest Guys Painting. Also around this time, Darren Blacketer and Chris Tipton were restoring Teddy Haggarty's murals on the extension of the building. In the summer of 2022 they installed a beer garden outside so that people could social distance and/or enjoy the warmth and sunshine. They even had a couple of bands play sets on the patio, and set things up for an outdoor open mic.

For a long time there was live music at the Jive every Saturday. Shows were all $5 as late as 2018, but by 2022 there are "monthly live music event[s]" and the price was usually $10 (though some shows cost less, and some were free). Between the pandemic and "den mother" Jenna Shrenk suffering a family loss that interfered with her gig-booking duties, the Jive has lost a bit of its presence in the music scene as a hot venue for local sound. These days it’s more of a karaoke/comedy bar, which frankly fits the vibe that Tacoma has going now. On Tuesdays there's open mic for poetry, singing, guitar or keys etc., and Bob's Comedy Jive is a weekly open mic comedy event on Thursdays.

2022 Yelp review: "The Java Jive is alive and well! Getting better every week. Cleaner, better beverage offerings while still keeping true to its gitchy legacy. Better beverages, better bathrooms!, better hours, better beer garden, better parking, better lighting, yet still the Java Jive!"

Bon Henderson said during her Tacoma News Tribune interview in 2021,

The people and stories [in Tacoma] are disappearing, brick by brick. I was born here. Things weren't perfect, and certainly not politically correct, and it was a tough town, but you learned to love all that. I want people moving here to know what Tacoma was all about. If we lose places like the Java Jive, they will never know. And that would be a damn shame.

Someone on Yelp called it "more like Bob's Java DIVE," and while that was probably meant to be an insult, it's accurate. The place is a dive. But that's kind of the point. This building and its history seem to emanate punk and grit and weirdness. It's been through hell, it's got a very mixed reputation, it's reinvented itself a few times, but for the most part these days it just kind of is what it is, the culmination of its history.

And if you're looking for coffee you can always go next door to KD'z Espresso shack...

PSYCH, IT'S CLOSED.

(Man, am I disappointed by the lack of coffee shops in this area!)

Bob’s Java Jive is currently open from 4pm to 2am, seven days a week.

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Portrait of a Lady on Fire: The Female Gaze in Film A video essay by Ella Boers and Ella Walken

This is two of my classmates’ joint final project for Sociology. I loved it so much I asked for their permission to share it here. Hope you enjoy it too!

Transcript under the cut, since the auto-generated captions are mostly accurate but punctuation is good for comprehension.

TRANSCRIPT:

“Boers: In 2019, French screenwriter and director Céline Sciamma released her fourth feature film, Portrait of a Lady on Fire. Following the narrative of two lesbian women, the movie highlights their story of love and art, and explores a woman's place in the society of 18th-century France. Sciamma's presence is a rarity in the heterosexual male-dominated film industry, as she is an out lesbian making films about her lived experience regarding sexuality. Her knowledge of queer womanhood manifests in quiet ways; a soft smile or longing gaze quietly and authentically conveys the depth of the love and respect women have for one another. While each of her films highlights stories which explore gender and sexuality, we will be focusing on Portrait of a Lady on Fire, where Sciamma portrays her characters as complex and multi-dimensional women.

Walken: Historically, women in film are portrayed as subordinate, less important, and one-dimensional in comparison to their male counterparts on screen. This unequal depiction of women in the media—called the "male gaze"—is everywhere in film, from more obvious movies such as Transformers and The Wolf of Wall Street portraying women as objects of pleasure for the heterosexual man, to Disney princess movies that more subtly objectify women through their sexy clothing and unrealistic body proportions. This is largely due to the movie industry being predominantly male-run, as producers continue to churn out the same material that has proved to be successful in the past. However, in recent years cinema has slowly been transitioning to a more accepting, equal, and diverse set of stories and characters.

Boers: Where the male gaze fixates on medium close-up shots of women from over a man's shoulder, shots of a woman's body, or scenes where a man is actively observing a passive woman, Sciamma directs the camera work in Portrait of a Lady on Fire so that it centers on her character's expressions and body language, revealing in them the complexity of the women's dreams and aspirations. In fact, Sciamma's execution of the female gaze encapsulates the women so well that when a man is shown on screen—an occurrence that only happens twice in the film's entirety—it comes as a shock to the viewer.

Walken: The main plot of Portrait of a Lady on Fire follows Marianne, a painter commissioned to do a portrait of bride-to-be Héloïse before she leaves for Milan to marry. As Marianne and Héloïse's relationship morphs into a passionate romance, the commentary on artist and subject becomes all the more apparent. Yet, as the relationship continues to blossom, it is still handled with the utmost care. Despite the fact that homosexuality was maligned in the setting of the film, Sciamma steers clear of any tired tropes in queer cinema, which often display and occasionally exploit trauma. Although the story is not unrealistic to its time period, the film chooses to take a caring route, never allowing a hint of the hate of the outside world to pervade into the relationship the couple shares. Even amidst a plot surrounding the painting of a woman's beauty, we as viewers experience with the characters what it means to be observed by a respectful female gaze rather than the aforementioned assertive male gaze, discovering a world where women can love and be loved for more than just their looks.

Boers: But beyond the directing and writing of camera work and plot, Sciamma's gaze extends—or rather, brings us back—to the 18th century, addressing limitations and societal norms that created obstacles for women, many of which still exist today. Marianne's profession as a painter was rather frowned upon for women of her time, and while girls of the middle and upper classes were encouraged to partake in the arts, taking it to a level past a leisurely hobby was viewed as losing sight of her priorities. Even women who did make the bold decision to pursue a career in art were restricted by their lack of access to art education. At the very simplest level, female painters were prohibited from studying live nude models, as it was considered indecent to do so. Their lack of education on the human anatomy limited the genres of which they could paint, and many, like Marianne, turn to portraiture for their primary specialty. On top of this, Portrait of a Lady on Fire touches on the life of an unmarried woman, challenging the common perception that a woman of that time is either married or to-be-married by instead portraying these women as content, having actively chosen their single lives.

Walken: A final important aspect of the female gaze in Sciamma's film is her attention to the complexity of women in all social classes. Similarly to Marianne and Héloïse, who fall into the higher classes of society, housekeeper Sophie is portrayed as complex and driven, despite her lower place on the social ladder. Towards the beginning of the film, Sophie finds out she is pregnant and enlists the help of Marianne and Héloïse in terminating her pregnancy. In addition to the abortion side-plot, all three women—no matter their economic status—are shown cooking, playing games, and enjoying the company of one another. In one particular scene, the two upper-class women work together to cook a meal while Sophie works on her art. Although a simple cinematic gesture, by including this small moment, Sciamma establishes Sophie as a character who is more than her work, and is allowed pleasure even by the women who she is working for.

Boers: Upcoming films such as Promising Young Woman and Wonder Woman 1984 continue to normalize the placement of women as main characters, centering the stories around the complexities of their lives and the depth of their potential. However, Sciamma's storytelling is unique in her ability to uplift women on screen without making a large gesture of it. Her film shows that the empowerment of women can be achieved through tender care, as she quietly explores the story of Marianne, Héloïse, and Sophie through the careful nuances of their friendship. Unknowingly, we are engulfed into a world where women have agency, where they can love, and where they have a depth to their character and dreams. Portrait of a Lady on Fire reflects the strength of the women in our modern world, and shows in its subtlety how to properly paint an image of a woman.”

End of transcript.

21 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

An Analysis on the History of Gender in the Horror Genre

This is one of my classmates’ final projects for Sociology. I loved it so much I asked for her permission to share it here. Hope you enjoy it too!

Transcript under the cut, since the auto-generated captions are mostly accurate but punctuation is good for comprehension.

TRANSCRIPT:

“My name is Davis Barelli, and in this video essay I'm going to look at the portrayal of gender through the lens of the horror genre.

Women in particular may have a reason to keep coming back to the genre, outside of a cheap thrill. In a study done by the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, and Google, using the Geena Davis Inclusion Quotient—or the GDIQ—it was determined that women are featured on screen and in speaking roles more than men only in the horror genre. With the advent of the MPAA rating system in the '30s, the kind of horror we know today didn't re-emerge until the '60s.

Making female characters who would later become known as "Final Girls" the vessel for traumatic experiences allowed viewers—especially men and boys coming home from war—to see someone reacting to trauma in the way that they wanted to, but wasn't socially acceptable. Instead, the model for men to see themselves in was the macho, womanizing jock who goes outside to find the big bad, typically resulting in him being the first to die. While there was a lot of good in the survivors of these horror movies very commonly being female, a specific archetype of the female survivor made it clear what kind of girl it took to be the hero.

The Final Girl being portrayed in '60s, '70s, and '80s slasher horror as an innocent virgin stereotype was no accident, what with America experiencing the breakdown of the nuclear family and Christian morals thanks to the free-love movement of the '60s. This led to frequent themes of occultism, homosexuality, and hypersexuality in horror at the time. Characters who gave in to these evils were given a death sentence, as opposed to the Final Girls, who were rewarded for their abstinence with survival.

When films did stray from the norm by casting male leads in sequels in place of the Final Girl, a double standard emerged. Male protagonists were branded as "homosexual" for acting like the Final Girls before them, and the actors who portrayed them had their careers effectively ruined. Where the '70s gave rise to exploitation horror centered on violence against women, '80s niche horror had different scapegoats.

Cannibal Holocaust, released at the beginning of the decade and directed by Ruggero Deodato, tells the story of a group going to the Amazon in search of a missing film crew. They discover footage detailing the gruesome things the crew did to the tribe they encountered before they were killed. Not only is the portrayal of hostile tribes in the Amazon harmful to the actual tribes in the Amazon, but framing the main character of the film as a kind of white savior for not wanting the footage of the tribe distributed is basically rewarding him for the absolute bare minimum.

The other standout film of the '80s notorious for its subject matter is that of Sleepaway Camp. Sleepaway Camp tells the story of a young girl who experiences the death of her family during a boating accident and is sent to live with her aunt and cousin. She and her cousin go to the summer camp and it quickly becomes a bloodbath. The reveal at the end is that the young girl was the culprit, because she wasn't a girl at all, but her twin brother who was forced by the aunt to live as a girl. The narrative of trans people as dangerous, deranged villains pretending to be a different gender due to mental illness or against their will is deeply harmful to the LGBTQ people who were battling misconceptions at the time similar to this, and still are.

This energy evolved with the '90s, which shifted its focus to supernatural teenage hormones, with the likes of The Craft and many others. Looking at the villains of these movies, though, is a clear pointer to the ostracization of the "weird kid" in the '90s. This is most prominently seen in The Craft, where a girl with supernatural powers befriends a group of girls pretending to be witches. She bestows them with real powers and hijinks ensue. The film culminates in the ringleader—who, out of the group, is the least conventionally attractive—being put in an insane asylum for her misdeeds, while the rest of the group gets off relatively scot-free. This served as an unfortunate continuation of the narrative that girls who were weird were to be punished, but if you were pretty, you could get away with it.

With the 2000s filled with American-made J-horror and classic horror remakes, I'd like to skip forward, save for one movie.

In the 2000s a movie came out that caused a huge ruckus over how bad it was, but I think deserves a spot here for its portrayal of teenage girls in horror. Jennifer's Body, directed by* Diablo Cody, starring Megan Fox and Amanda Seyfried, tells the story of Jennifer getting possessed after a botched human sacrifice because she lies about being a virgin. It was almost universally panned by critics, who called it a "sexploitation film lacking the all-important ballast of sincerity." Both Cody and Fox—who were gaining fame for Juno and the Transformers franchise, respectively—were already written off by critics, most of whom were men, before the movie had even been released. In reality, Jennifer's character was unique for being the mean girl who gets killed off, the big bad, and a revenge film-esque survivor, all in one. And her best friend, "Needy," was the sarcastic, dorky, sexually active Final Girl we never would have seen in classic horror.

The last decade has given rise to a genre dubbed "intelligent horror," ushering in an age with less mindless bloodlust and more nuanced characters and themes. Directors Jordan Peele and Ari Aster are arguably at the forefront of the intelligent horror genre; Peele's Get Out and Us giving people of color representation in a severely whitewashed genre. Get Out, especially, has received praise not just for the representation of people of color, but the very real, very prevalent issues of race and police brutality. One of the most important aspects is the depiction of the white savior character in the form of the protagonist's girlfriend, who is revealed to actually be a villain, showcasing the dramatization of the danger of performative activism and how that affects people of color.

Ari Aster, on the other hand, deals with themes of mental illness and family trauma, something unfortunately somewhat universal. While mommy issues and cults are nothing new in horror, Ari Aster's work frames both subjects very differently, especially in regards to the women in his films. Midsommar heavily focuses on Dani, the protagonist's, mental health and manipulation by others throughout the film, as she navigates grief unapologetically and realistically. This portrayal of grief in Midsommar from a woman's point of view is so important, because Dani is clingy, she's anxious, she's emotional, and she's human. As opposed to the polished, over-dramatic depiction of women and their emotions that are so commonly seen in horror.

Over the decades, horror and its portrayals of the human experience have shifted to continue being a compelling mirror for the issues of the time. But something that will always be current is that we can be scared.”

End of transcript.

*Jennifer’s Body was written by Diablo Cody and directed by Karyn Kusama

22 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Lukewarm Take on Bee Movie for Sociology I could have said so many more things about this movie but I had to keep it short for class. I wrote a bunch of junk about the military-industrial complex and hegemonic masculinity, about capitalism and the status quo, about racial depictions and the whole chattel slavery allegory, about Jewishness... but I'm barely qualified to talk about half of that stuff anyway so it's probably best that I stuck to basics here. Sometimes I mumble or slur my words, so turn on the captions for the script! They are not auto-generated, they are accurate to what I'm actually saying.

References: Gloudeman, N. (2014, October 2). Tom & Jerry Wasn't Just Racist, It Was Sexist Too. Ravishly. http://www.ravishly.com/2014/10/02/tom-jerry-amazon-racism-racist-disclaimer-censorship Neville, C., & Anastasio, P. (2018 August 14). Fewer, Younger, but Increasingly Powerful: How Portrayals of Women, Age, and Power Have Changed from 2002 to 2016 in the 50 Top-Grossing U.S. Films. Sex Roles (2019) 80:503–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0945-1 Quinton Reviews. (2018, July 13). The story of Bee Movie [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=897X1J_vxj8&t=822s Xu, H., Zhang, Z., Wu, L., & Wang, C. (2019, November 22). The Cinderella Complex: Word embeddings reveal gender stereotypes in movies and books. PLoS ONE 14(11): e0225385. https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0225385

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

SOC 120 Blog 5: We Are Not a Wave, We Are the Ocean

What the heck is a "wave" of feminism? The "first wave" secured women's right to vote. The second gave us access to abortion. Now we're in the third wave and we're doing trans rights. Right? It's more complicated than that. As Constance Grady wrote for Vox in 2018:

The wave metaphor can be reductive. It can suggest that each wave of feminism is a monolith with a single unified agenda, when in fact the history of feminism is a history of different ideas in wild conflict.

It can reduce each wave to a stereotype and suggest that there’s a sharp division between generations of feminism, when in fact there’s a fairly strong continuity between each wave — and since no wave is a monolith, the theories that are fashionable in one wave are often grounded in the work that someone was doing on the sidelines of a previous wave. And the wave metaphor can suggest that mainstream feminism is the only kind of feminism there is, when feminism is full of splinter movements.

And as waves pile upon waves in feminist discourse, it’s become unclear that the wave metaphor is useful for understanding where we are right now. “I don’t think we are in a wave right now,” gender studies scholar April Sizemore-Barber told Vox in January. “I think that now feminism is inherently intersectional feminism — we are in a place of multiple feminisms” (Grady, 2018).

So with the understanding that this framework is kind of reductive, let's surf these supposed "waves" a little.

The first wave (1848 to 1920) did indeed centre around women's suffrage for the right to vote. Suffragettes were originally abolitionists, but then got mad when Black men—former slaves—got the vote before them, and Black women were often barred from or forced to walk behind white women during suffrage marches. Margaret Sanger opened the birth control clinic that would become Planned Parenthood during this wave. Women also worked to secure equality in education and employment, though there was a double standard when it came to women in the workplace; Black and brown women were considered less ladylike and more capable of labour, while white women were protected by the white men who held power, considered delicate and expected to stay in the home and raise children. There's some of those differing agendas within the movement.

The second wave (1963 to the 1980s) was called such because it had seemed that feminist activity had died down until Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique in '63, sparking a new "wave" of feminist activity. She talked about "the problem that has no name," which was that white middle-class women's "place" was in the home and they were being pathologised if they didn't like being stuck doing housework and childcare.

The Feminine Mystique was not revolutionary in its thinking, as many of Friedan’s ideas were already being discussed by academics and feminist intellectuals. Instead, it was revolutionary in its reach. It made its way into the hands of housewives, who gave it to their friends, who passed it along through a whole chain of well-educated middle-class white women with beautiful homes and families. And it gave them permission to be angry (Grady, 2018).

The phrase "the personal is political" comes from this time; the idea that small things that can seem like individual problems are actually a result of systemic oppression. Systemic sexism is defined as "the belief that women’s highest purposes were domestic and decorative, and the social standards that reinforced that belief" (Grady, 2018). Other things that were fought for during this time include equal pay; access to birth control (and an end to forced sterilisation of Black and disabled women); educational equality; Roe v. Wade and the right to have consensual abortions; political independence rather than being legally subordinate to husbands; working outside the home (for white middle-class women); awareness of and an end to domestic violence and sexual harassment. Some of the same things that women of the first wave were fighting for. Black feminists, however, were starting to get tired of white people obliviously hogging all the limelight; bell hooks "argued that feminism cannot just be a fight to make women equal with men because not all men are equal in a capitalist, racist, homophobic society" (University of Massachusetts, 2017). This started the tradition of Black feminist thought and womanism.

The third wave, starting in the 1990s and inspired by work in the 80s, embraced a lot of stuff that the second wave rejected.

In part, the third-wave embrace of girliness was a response to the anti-feminist backlash of the 1980s, the one that said the second-wavers were shrill, hairy, and unfeminine and that no man would ever want them. And in part, it was born out of a belief that the rejection of girliness was in itself misogynistic: girliness, third-wavers argued, was not inherently less valuable than masculinity or androgyny (Grady, 2018).

In this time we had the riot grrrl phenomenon on the music scene; the continuation of the fight that started in the 80s for access to medical treatment for HIV/AIDS and the humanisation of queer people; queer politics which emphasise that there are more types of queers than just middle-class white gay men and lesbians; sex-positive feminism advocating for sexual liberation and consent; and transnational feminism, which "highlights the connections between sexism, racism, classism, and imperialism" (University of Massachusetts, 2017). Kimberlé Crenshaw's coining of the term "intersectionality" in the 80s to refer to the intersections between different kinds of oppression (woman AND Black, woman AND disabled, woman AND immigrant, etc.), became the name of the game.

Arguably, we are now in a fourth wave of feminism, an online wave, which "is queer, sex-positive, trans-inclusive, body-positive, and digitally driven" (Grady, 2018). We use hashtags like #MeToo on Twitter and we organise SlutWalks online and we circulate our revolution magazines with hyperlinks rather than paper. We don't have to attend a rally in order to make our presence known, and we don't have to leave the house and gather together in person in order to hear each other's stories and energise each other to act. We're enabled to be lazier, but we're also enabled to do something with minimal energy when we don't have very much due to a medical condition or other disability. We don't have to exhaust ourselves after work by driving or walking to another meeting place, we only have to log on. We face less physical danger online than we do on the streets. We're empowered in different ways than our predecessors were, and we have access to information and audiences in a way they could never have dreamed of.

I won't go into too much detail about the conflicts between generations or "waves" of feminism like Grady does in her Vox article. There will always be squabbling amongst group members. There will always be splinter movements off of the "mainstream" effort. The focus should be on the goal that we all share, that of ending some kind (or all kinds) of oppression. We should be helping each other to achieve that goal and promote real equality, not letting ourselves be divided along temporal, generational, racial, gender, or any other kind of lines. Coalitional feminism is essential—"politics that organizes with other groups based on their shared (but differing) experiences of oppression, rather than their specific identity"—the opposite of identity politics, which revolve around one identity at a time (University of Massachusetts, 2017).

Unity can be difficult when some groups consider their aims fundamentally at odds, but tearing each other down rather than working to tear down the walls that separate the marginalised from the mainstream is just wasted energy. So while the wave structure can be useful when talking about different "main" events in the historical record of feminist activism, ultimately it just attempts to neatly compartmentalise something that has always been vast and complex and noisy. Feminism's nuances are part of its legacy. If there is anything that all feminisms have in common, it is that we have always been a thorn in the side of the establishment.

Vox as a media corporation is a bit left-leaning, but feminism also tends to be left-leaning. Their niche is in explaining political and social goings-on to a lay-public who may not be keeping up with all the news regarding any given topic. Their sources are credible and their reliability is rated highly by Ad Fontes Media and Media Bias/Fact Check.

[1,432 words]

Grady, C. (2018, July 20). The waves of feminism, and why people keep fighting over them, explained. Vox. https://www.vox.com/2018/3/20/16955588/feminism-waves-explained-first-second-third-fourth

“Introduction to Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies” by University of Massachusetts, 2017. CC BY Creative Commons Attribution 4.0.

(http://openbooks.library.umass.edu/introwgss/)

0 notes

Text

SOC 120 Blog 4: Women, Work, and COVID-19 Makes Three

This week in Sociology is all about women in the workforce (and other work that women perform). A hot topic is emotional labour, which is work that requires the employee to manage not only their own emotions—can't blow up at a customer, no matter how loudly they're screaming insults and slurs in your face, lest ye be fired—but also the emotions of the customers, to keep them calm when they're unhappy with service or keep them happy enough to tip (University of Massachusetts, 2017). Other vocab: glass ceiling, or the barrier that stands between women and high-level positions; glass escalator, or the fast-track that men tend to find themselves on in female-dominated occupations, including higher pay than their female peers; and feminised or pink-collar work, which are jobs that are considered to be "women's work" and are frequently seen as less valuable and deserving of less wage compensation (University of Massachusetts, 2017).

We also talked quite a bit about globalisation, neocolonialism, and other broad-stroke issues that women deal with in the modern world, but I'm going to be U.S.-centric here, because that's where I live.

CNBC's Courtney Connley reported in October on an analysis from the National Women's Law Center that broke down the numbers of Americans who were dropping out of the workforce in August. Those numbers go something like this...

people aged 20+ who are no longer working or looking for work: ~1.1 million portion of those people who are men: 216,000 portion of those people who are women: 865,000 (Connley, 2020)

That's quite a bit more women than men. Four times as many. Why on Earth are so many more women than men dropping out of work? For the same reasons women usually quit working at much higher rates than men: Childcare.

If a male-female couple have a child or children to raise together, but aren't rolling in the kind of dough that it takes to pay a nanny what they're worth, it "makes sense" for one of them to stay home to care for the house and progeny while the other one works. That's how the American Dream has worked for decades anyway, right? That was sarcasm. That nuclear breadwinner-homemaker model only worked for middle class white people anyway and is no longer sustainable even for them given wage stagnation and rising living costs (University of Massachusetts, 2017). So now it's less of a well-oiled gender stereotype machine and more of a necessity—but it's still broken down gender lines, because of the gender pay gap. Since women earn less than men, having the mother bring home an average of 77% percent of the bacon that the father could be bringing, while the father stays home to do a job that he'll likely be ridiculed for doing by his peers, doesn't sound like it makes a lot of sense to a lot of families (University of Massachusetts, 2017). So now we have close to a million women leaving the workforce because a disease is making a difficult economy even worse.

Today's problem echoes yesterday's problems, and race is always part of the equation. While September is presenting white men and women with, respectively, a 6.5% and 6.9% unemployment rate, Latina women have to deal with an 11% rate, and Black women an 11.1% rate (Connley, 2020). But even those who still have money coming in are not spared from the inequity; Sheryl Sandberg says mothers who work still have to come home to the "second shift" where they continue to do domestic work on top of their day jobs, and on average they're putting in 20 hours more per week of this house- and child-care labour than fathers are (Connley, 2020). On top of this, they have to worry that their at-home duties are burning them out or that their bosses perceive such burnout (with potential consequences for their job security).

Long story short: Women usually have the short end of the stick. COVID-19 has made the whole stick shorter, but some of us are faring less well than others in trying to keep our hold. Public sector work may not be seen as valuable to a culture that worships the dollar, but that's the kind of work that is literally saving lives right now, so supporting those people should probably be a priority for a country that has some pretty high case numbers.

On credibility: Courtney Connley is a careers reporter for CNBC's Make It. CNBC as a network has a history of credibility and trustworthiness and a focus on financial and business news, which makes them a sensible place to seek information about workforce statistics. The source used for this article is the National Women's Law Center, an organisation whose purpose is to fight for gender justice.

[808 words]

References

Connley, C. (2020, October 2). More than 860,000 women dropped out of the labor force in September, according to new report. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/10/02/865000-women-dropped-out-of-the-labor-force-in-september-2020.html

“Introduction to Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies” by University of Massachusetts, 2017. CC BY Creative Commons Attribution 4.0.

(http://openbooks.library.umass.edu/introwgss/)

1 note

·

View note

Text

SOC 120 Blog 3: It Sucks to be Female (But it Sucks More in War)

This week was difficult for me for a few reasons, but a big one was the emotional toll of my Sociology reading. We read about the fact that one-third of women have been domestically abused and/or raped globally, and the fact that most women will not report these crimes because of the stigma against reporting, or against having been abused or raped, or because they are afraid of retribution from their abusers, or because they rely on their abusers' financial and family support, or because they think that being beaten and/or forced to sexually fulfill their partner is a normal part of relationships (it's not) (University of Victoria, 2012). We read about how the rates of this abuse are higher in areas that have patriarchal societies, where women are not allowed to leave the house, work, own property, or seek divorce from their abusers (University of Victoria, 2012). We read about the high rates of missing Indigenous women and the fact that in most cases almost nothing is done to try to find them, including the basic first step of reporting their missing status on the news (ABC News, 2019). We read about child marriage and human trafficking. We read about how women in areas affected by violent conflict face not only domestic rape but also war-related crimes intended to drive the current population of an area out so that the invading forces can take control of valuable minerals and other resources in the area, and how this is done by raping women in front of their families in the hopes that they will suffer honour killings ("the killing of females by male relatives to restore family honor" (University of Victoria, 2012: Chapter 4)) or by torturing them—by gang-raping them, mutilating their genitals, raping and killing their children, or otherwise making them suffer horrendous physical and psychological pain.

On the brighter side, we read about people who are speaking out against this systemic violence and anti-woman sentiment, women who help victims of wartime rape and peacetime domestic violence. About how women are the most vocal advocates for peace before and during conflict, and despite the fact that they are often pushed to the side during the actual peace negotiations, when women are deliberately and centrally included in those negotiations, the peace tends to be more comprehensive and last longer (University of Victoria, 2012).

I want to talk about the excitement around the all-female UN peacekeeper units from India (University of Victoria, 2012), the UN's goal to increase the number of women among its ranks, and a Vice report from two years ago.

In July of 2018, I watched this Vice expose on the prevalence of sexual misconduct among UN peacekeepers. That is, the high number of rapes committed by male peacekeepers, and the lack of action taken by the UN to condemn, discipline, or bring justice to the men committing these rapes on women and children (yeah, kids, as young as nine (VICE, 2018)) who they were supposed to be guarding from enemies and helping through struggles. In many cases, the UN was not even reporting these incidents, and some of the attempted reports made by whistleblowers were actively suppressed in order to cover up the crimes. The whistleblower Vice interviewed was, in fact, a female peacekeeper, and while she felt compelled to do the right thing instead of looking the other way or protecting her fellow officers, she was just one woman in the face of a system composed of more than 90% male on-the-ground UNPOLs (United Nations Police officers) and 79% male leadership (United Nations, n.d.). So leaving aside the atrocities being committed upon these women and children by the attacking forces, they are also being taken advantage of by the forces deployed to assist them through conflict, and the perpetrators face nearly zero punishment for their actions.

The textbook, the women activists who helped write it, and the UN itself all believe that more women in these positions is a good thing for equality's sake and because women have a lot to offer in times of strife. I agree. I think a large part of the reason these atrocities are allowed to slide out of view is the deeply-rooted, global culture of rape apology. I think if more women are present on the ground when these things happen, they will be reported more. I think if more women are in positions of power higher up the chain of command, less reports will get "lost" or ignored. I think if the number of women in spheres of influence reflects the number of women on the planet, men will have much less room to bully each other into boys' club mentalities and will be much more incentivised to watch their behaviour. I think a large part of the reason such violent human rights abuses occur all over the world is misogyny, and while not all misogynistic thought comes from men, the majority of misogynistic violence is perpetrated by them, so that's the most obvious place to start.

Vice Media is a cultural/political magazine-turned-media company which does a lot of reporting on international events. Their primary audience is young people and thus they are a bit left-leaning, since young people tend to be more progressive. Funnily enough, the upper management of the company had a reputation for "bro culture" and hostility to women until its current CEO Nancy Dubuc took over in 2018 and changed things up a bit (Influence Watch, n.d.). The information in this particular video is only a couple of years old at time of writing and a lot of it comes directly from the mouths of the people involved, per video journalism standards.

[983 words]

References

ABC News. (2019 October 9). Indigenous student’s disappearance just one in epidemic of missing native women | Nightline [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sVEAjOSnx8c

“Global Women’s Issues: Women in the World Today” by University of Victoria, 2012. CC BY Creative Commons Attribution 4.0.

(https://opentextbc.ca/womenintheworld/)

Influence Watch. (n.d.). Vice Media Group. https://www.influencewatch.org/for-profit/vice-media-group/

United Nations. (2016 December 17). “Far to go” to incorporate women leadership in the UN. UN News. https://news.un.org/en/audio/2016/12/620632

VICE. (2018, July 27). Peacekeepers turned perpetrators [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RZfoCHEIfDQ

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

SOC 120 Blog 2: Breaking Binaries

This week I'm linking in-class concepts from the open educational resource textbook “Introduction to Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies” by the University of Massachusetts with the article "What’s the Real Difference between Bi- and Pansexual?" by Zachary Zane for Rolling Stone.

To begin, let's define "binary." University of Massachusetts defines binaries as social constructs composed of two parts framed as absolute, unchanging opposites (University of Massachusetts, 2017). The sex binary tells us that there is only male and female, but we know that's not true: Intersex people exist—those whose genitalia were "ambiguous" at birth, or who have chromosomes or hormones or internal sex organs that don't "match" their perceived sex category. The gender binary tells us that there is only man and woman, but various types of nonbinary people tell us that their experiences fall outside this dichotomy. Even the way cis people experience their masculinity or femininity is not a binary: There are masculine women and feminine men, and cis people who are androgynous, combining elements of masculinity and femininity into their appearance and self-concept. And, of course, there is a sexuality binary—straight and gay—but that, too, is not the whole story. Bisexuality is one label for someone who is not monosexual, or not attracted to only one gender. But even this binary-breaking identity is seen as a binary concept. It is sometimes defined as "the attraction to men and women," a limitation harkening back to the sex and gender binaries that we just debunked.

The history of bisexuality as an identity and as a definable category is fraught with disagreement, from the technical to the political. Some say that in order to reject binary thinking as a society we must reject words that reinforce binary concepts, including the word "bisexual." The argument goes that the latin prefix "bi" means "two," so "bisexual" must mean "attracted to two genders" and no more. In contrast, another commonly used identity label is "pansexual," which contains the prefix "pan," meaning "all." The difference between these two labels is the subject of Zane's Rolling Stone article, and a lot of people have a lot of opinions about what each of them means and which is better. Some argue that anyone who is attracted to more than two genders should abandon bi and embrace pan, because of the two/all difference in their prefixes. But it would be asking a lot of people who identify as bisexual and are attracted to more than two genders to give up their sense of identity and community in order to adopt a new, "better" word. To force the issue would be to dictate bisexuals' identities to them and to overwrite a long history of bisexual attraction to intersex, gender-nonconforming, agender, and other nonbinary people.

Might there be people who identify as bisexual and choose to define that label for their own personal use as attraction to men and women and only those two? Perhaps even only cis men and cis women? Absolutely. But there are also monosexual people who choose to reject transgender or nonbinary people from their pool of potential partners because of reasoning like, "I'm attracted to women, but not trans women, because they're not really women." That's not an issue of their sexuality label failing to describe their attractions, that's just transphobia. Put another way: There are undoubtedly transphobic bisexuals*, just as there are transphobic monosexual people. But we call those people transphobic as an additional label, rather than inventing a word that means "attracted to only cis men" or "attracted to only cis women" to replace whatever they currently identify as.

None of this is to say that bisexuality is the only non-monosexual label that should be used and that labels like pansexual should be abandoned. If a person feels uncomfortable with the possibility of being thought of as transphobic or reinforcing the gender binary or just perceived as having a limited scope of attraction, of course they should use a different, more affirming label. And considering how much drama there is surrounding the word "bisexual," it might just be something that some people don't want to deal with, and thus a different label is more comfortable in that it doesn't have to be justified by the person using it. But others of us don't mind justifying our label, or challenging those who would assume or prescribe our sexuality to us. Some of us think that this word, which calls to mind the very binary that we reject, and is consistently targeted by nit-picking people who bring up semantic and etymological arguments against it, has a history that is worth preserving and respecting. Or maybe we just like the way it sounds. Because, frankly, if someone identifies as bi they risk getting flak from pan-identifying people for not being inclusive enough, but if they identify as pan they have a high likelihood of having to deal with monosexual people who think that making a joke about being sexually attracted to frying pans is original, witty, and hilarious.

This notion of claiming different identify labels depending on who's asking is touched upon in the Rolling Stone article by actor and queer activist Nico Tortorella: “If I’m talking to somebody who’s more conservative and doesn’t believe in a nonbinary gender, then it’s easier to use the word bisexual, but if I’m talking to someone who’s invested in gender, queer theory, and understands the spectrum, then I’m more comfortable using the word ‘pansexual’ or the word ‘fluid.' (Zane, 2018)” Alternately, some people just use "queer." This is kind of vague, but why does it need to be specific? It conveys that a person is not straight, which does the job for a lot of not-straight people, especially if they want to avoid the sticky mess of choosing between labels like bi and pan. It can also be inclusive of nonbinary people who hesitate to use labels like "gay" or "straight" because those terms don't easily fit a person who is not a man or a woman with an easily definable "same" and "different" gender category.

To close, I'd like to directly address the notion that "bi" means "two." It's easy to get hung up on technical meanings of words, and to forget that language is a living, changing thing. Gabrielle Blonder from the Bisexual Resource Center is quoted in the Rolling Stone article as saying, "Much like October is no longer the eighth month of the year, I believe the term bisexual has morphed into a different meaning than it originally was.”

Due to the social nature of this topic, a magazine article featuring quotes from interviewed people is perhaps more appropriate than a scientific article. Rolling Stone has a reputation for being "plugged in" to subcultures rather than popular culture, and for having more tolerance for the strange and rejected in society than other similarly well-known publications. It is, however, slightly more credible than, say, a blog post, due to the credentials of a journalist writing for a respected publication with high standards and a large audience holding it to accountability.

* transphobic or simply non-trans-attracted. One of the people interviewed in the Rolling Stone article says that they accept trans people and their rights, but cites their sexuality as including attraction to only cis men and cis women. It is a matter of debate whether this is just personal preference or is inherently transphobic. The same debate exists for monosexual people who are attracted to only one gender and one sex, either because they believe that gender and sex are inherently linked (which is transphobic because it invalidates the very existence of trans people) or because they are only attracted to one gender presentation and one type of genitalia (which may or may not be transphobic depending on who you ask, and does not consider whether a trans person has had sexual reassignment surgery).

[1,327 words]

References

“Introduction to Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies” by University of Massachusetts, 2017. CC BY Creative Commons Attribution 4.0.

(http://openbooks.library.umass.edu/introwgss/)

Zane, Z. (2018, June 29). What's the Real Difference between Bi- and Pansexual? Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/whats-the-real-difference-between-bi-and-pansexual-667087/

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Social Construction of Heterosexuality

What does it mean to be “heterosexual” in contemporary US society? Did it mean the same thing in the late 19th century? As historian of human sexuality Jonathon Ned Katz shows in The Invention of Heterosexuality (1999), the word “heterosexual” was originally coined by Dr. James Kiernan in 1892, but its meaning and usage differed drastically from contemporary understandings of the term. Kiernan thought of “hetero-sexuals” as not defined by their attraction to the opposite sex, but by their “inclinations to both sexes.” Furthermore, Kiernan thought of the heterosexual as someone who “betrayed inclinations to ‘abnormal methods of gratification’” (Katz 1995). In other words, heterosexuals were those who were attracted to both sexes and engaged in sex for pleasure, not for reproduction. Katz further points out that this definition of the heterosexual lasted within middle-class cultures in the United States until the 1920s, and then went through various radical reformulations up to the current usage.

Looking at this historical example makes visible the process of the social construction of heterosexuality. First of all, the example shows how social construction occurs within institutions—in this case, a medical doctor created a new category to describe a particular type of sexuality, based on existing medical knowledge at the time. “Hetero-sexuality” was initially a medical term that defined a deviant type of sexuality. Second, by seeing how Kiernan—and middle class culture, more broadly—defined “hetero-sexuality” in the 19th century, it is possible to see how drastically the meanings of the concept have changed over time. Typically, in the United States in contemporary usage, “heterosexuality” is thought to mean “normal” or “good”—it is usually the invisible term defined by what is thought to be its opposite, homosexuality. However, in its initial usage, “hetero-sexuality” was thought to counter the norm of reproductive sexuality and be, therefore, deviant. This gets to the third aspect of social constructionism. That is, cultural and historical contexts shape our definition and understanding of concepts. In this case, the norm of reproductive sexuality—having sex not for pleasure, but to have children—defines what types of sexuality are regarded as “normal” or “deviant.” Fourth, this case illustrates how categorization shapes human experience, behavior, and interpretation of reality. To be a “heterosexual” in middle class culture in the US in the early 1900s was not something desirable to be—it was not an identity that most people would have wanted to inhabit. The very definition of “hetero-sexual” as deviant, because it violated reproductive sexuality, defined “proper” sexual behavior as that which was reproductive and not pleasure-centered.

from an open-source text on academic feminism: Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, Sonny Nordmarken; licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License; http://openbooks.library.umass.edu/introwgss/chapter/social-constructionism/

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

SOC 120 Blog 1: Sex, Gender, and Roles

When we think of gender and power, often the first thought we have is men's power over women. And of course, in a patriarchal society that's the bottom line. But that oversimplifies the problem, and overlooks other interactions between people of the same gender which reinforce the broader male/female dichotomy.

Women are famous for being hypercritical of each other. And sometimes, this can stem from jealousy when a woman is more sexually attractive to men and thus a competitive threat for access to sexual partners. After all, if a woman takes down someone who's prettier than her, there's a wider pool of men for that woman to choose from in her absence. What, then, is the reason for socially punishing women who aren't trying to make themselves attractive to men? Wouldn't a woman being "unfeminine" simply write her off as competition and thus make her performance of her gender not other women’s problem?

Emphasised femininities are forms of femininity which conform to men's ideal of women (Coleman, 2017). To reject this kind of gender performance is akin to aligning oneself with boys and men, and therefore to become a threat to other women not in a sexual competition but in the arena of gender stratification itself (Peachter). Performing masculinity instead of the kind of femininity that is expected of women is dangerously close to acting "above your station" in a world where women and femininity theoretically belong squarely underneath men and masculinity in the hierarchy. Thus, straying from the emphasised feminitities which signal a woman (or anyone else who is expected to perform femininity) as being compliant with their own female subjugation results in not only men trying to put them "back in their place," but also other women lashing out to protect themselves from the unfairness of one of their own ascending beyond the imposed limitations.

On the flip side, masculinity needs to be enforced by its practitioners as well. It's called hegemonic masculinity: the ideal way of being a man which other ways must interact with, either to conform to or challenge it (Coleman, 2017). This can be stifling for men (and others who are expected to perform masculinity), who have to either face ridicule for being nonconforming or squeeze themselves into one of only a few boxes, regardless of personal interests and aspirations. As an example: in Ireland, up until the middle of the last century, those options were limited to only priest or working family man (Morettini, 2016). In the U.S., we have more than two "manly" options available to men, but the number is still limited, and the consequences of not fitting into one of the boxes range from uncomfortable to severe and even deadly. The most common ways that men stray from the paradigm of accepted and enforced masculinity are by belonging to the LGBTQ community or behaving "effeminately"—like a woman (Morettini, 2016). These groups also often overlap, partly due to the fact that they both deviate from the masculine ideal.

This structure, that of hegemonic masculinity and its feminine counterpart, operates on the local, regional, and global levels (Morettini, 2016), meaning it's a very tangled web to try to unweave. The good news is that establishing rights for women and queer people "trickles down" to men: by eliminating second-class-citizen norms, men will no longer face such extreme social danger for slipping out of the position of power—being “emasculated.” The more the lines are blurred between "real man" and other categories that look too much like "woman" or "gay," the less violence needs to be enacted to reinforce the hegemony. And the less stark the differences between "man" and "woman" in a performative sense, the less danger women and queer people face simply for existing as a second-class human being.

[631 words]

References

“Intro to Women’s Studies” by College of the Canyons, 2017. CC BY Creative Commons Attribution 4.0.

(https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1-GWctzm4yQuS7XTF3so_S4r5iGUYQOzK)

Crash Course. (2017, November 16). Gender stratification: Crash course sociology #32 [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yb1_4FPtzrI&feature=emb_logo&ab_channel=CrashCourse

Morettini, F. M. (2016). Hegemonic masculinity: How the dominant man subjugates other men, women and society. Global Policy Journal. Retrieved from https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/27/10/2016/hegemonic-masculinity-how-dominant-man-subjugates-other-men-women-and-society

Paechter, C. (n.d.). Masculine femininities/feminine masculinities: Power, identities and gender. Gender and Education, 18(3). Retrieved from https://research.gold.ac.uk/1551/1/EDU_Paechter_2006a.pdf

3 notes

·

View notes