Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

The Christ Pantocrator of the Deesis mosaic, 13th century, in Istanbul.

221 notes

·

View notes

Photo

four elements

Ovide moralisé en prose, Bruges ca. 1470-1480

BnF, Français 137, fol. 1r

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

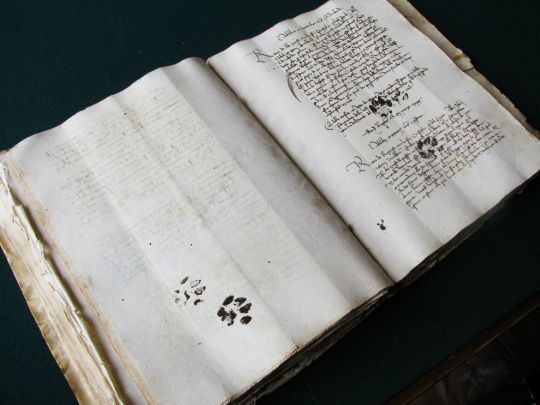

Paw prints from a cat on a 15th century manuscript

54K notes

·

View notes

Text

Formal Analysis of Édouard Manet’s “The Dead Christ With Angels”

23 February 2016, Introduction to Modern Art at the University of Kansas

In Édouard Manet’s The Dead Christ with Angels (1864), Manet examines themes of religious significance through the depiction of Christ following his crucifixion. The work, a large scale piece that is just under life-size, is meant to be oriented vertically. The artist shows Christ, located in the center of the composition, accompanied by two angels to his left and right, balancing the scene and holding up Christ’s body so the viewer can see him.

Manet centers the composition around the body of Christ in the center of the piece, dominating it. His hands are open, revealing the crucifixion wounds on his hands. An angel stands both to Christ’s left and right, both balancing the scene while also commanding the rest of the space around Christ. The angel to Christ’s right leans towards the left side of the frame, away from Christ, while the angel to Christ’s left leans towards Christ, also towards the left side of the frame. This composition allows the viewer’s eye to follow the angel on the viewer’s left to create the start of the line that draws the eye through the scene. Beginning with this angels wing, Manet creates a line that goes down to the angel’s face and right hand, to the line in the center of their gown, over to Christ’s right hand and over through the folds of his perizoma (Christ’s loincloth worn during his crucifixion) to his left hand, up the left arm of the angel to Christ’s left to the angel’s face, and lastly up to the tip of the angel’s wing in the upper right corner of the piece. The rest of the composition is empty except for a scattering of rocks and a snake found in the lower right hand corner of the picture plane. Although the rocks and the snake are small in comparison to the dominating presence of Christ and the angels, those objects make up the primary foreground of the painting. Christ, located in the center of the piece, makes up the middle ground, while the two angels behind him are in the background. There is a clear distinction between the three sections of the piece. However, the angel on the right side of the piece breaks into the middle ground with the arm that is reaching out to grasp Christ’s arm.

Manet enforces Christ as the focal point by dressing him in bright white, creating contrast between the lightness of Christ and the darker colors in the tomb. His perizoma is white, but he is also surrounded by what appears to be a bright white burial shroud, encasing him in a white cloud of vibrant color that hints at his divine nature and brilliance without literally encasing him in the glowing divine light typically surrounding him in many depictions. In contrast, the angels are clothed in jewel tones of red, yellow and blue, making their skin appear white and delicate, as opposed to Christ’s muddy skin tone. The tomb itself is a dull grey and brown. With the exception of the brilliant jewel tones clothing the angels, Manet uses a natural palette of grey, brown and white, creating a dark atmosphere within the picture plane. The bright white of Christ’s perizoma and shroud and the mustard yellow of the angel’s robes are the brightest colors in the painting, bringing them out of the shadows of the tomb and into the awareness of the viewer. The ruby red of the other angel’s robes is the darkest color, which pushes them further into the background and the shadows. The colors of the angels’ robes puts them in a position of importance, as they seem more regal than a normal person would, but the darker colors put them in a secondary position when compared to Christ, emphasizing the divine hierarchy.

Manet uses light and shadow to emphasize Christ’s divine status similarly to his use of color to create an illustration of the divine hierarchy. Christ and the angels are lit with a natural light source coming from the lower left corner that seems to come from the same space as the viewer, as though the viewer is standing at the opening of the tomb, looking in at Christ and the angels within. Christ is the most fully lit figure within the space, drawing the eye to him and acknowledging his status as the Son of God, while also emulating the divine light of Christ using a natural, outside light source instead of a pulsing, unnatural light from Christ himself. The figures in the piece are modeled through the use of light and shadow, giving them definition that is only created through the way light hits the human form. This modeling creates the appearance of being three-dimensional, bringing them to life within the piece. There is a stronger emphasis on light and shadow, rather than the use of bright and dominating colors, to create the atmosphere of a dark, grimy tomb. The dense, moody shadows imply grief, as the mourning angels struggle to support both the body of Christ and the knowledge of his death and eventual resurrection, while the bright light of the natural light source enveloping Christ suggests the hope of the impending resurrection.

The brushstrokes created by Manet are observable, but they are soft in a way that creates very natural textures in the skin and cloths present in the piece. The treatment of the angels’ garments shows the most paint thickness, which creates the appearance of thick, luxurious robes. The brushstrokes in the creases of the robes, especially in the yellow robes, creates realistic lines in the fabric, notably in the lines around the angel’s leg nearest to Christ’s left hand. Other thick and noticeable brushstrokes can be found in Christ’s hair and beard, which creates the illusion of thick, curly hair that looks rough and textured to the eye of the viewer. This is not the standard throughout the painting, however. For example, the artist applies paint to Christ’s body in a thinner manner, which makes it seem delicate, despite the grime and wounds on his body. There are no pencil marks or visible canvas portions that would detract from the purpose and intended presentation of the painting.

Édouard Manet’s The Dead Christ with Angels depicts Christ following his crucifixion at the hands of the Roman Empire; unlike many other depictions of Christ, it is not immediately obvious that the man in the center of the composition is in fact the Son of God. He is dirty, plain and unruly in appearance and lacks any traditional symbolism acknowledging his divine status, such as a mandorla. However, he has the wounds of a crucified man on both of his hands and on his feet and is flanked by two brightly dressed angels, identifying him as Christ. This subtle acknowledgment of Christ’s divinity is enforced by Manet’s use of brilliant white color to highlight Christ and a distinct use of light and shadow to envelop Christ in natural light, while demoting the angels in the shadows, creating a moody, sorrowful scene that focuses on Christ himself as a man, rather than as a divine being capable of divine miracles and an impending resurrection.

0 notes