Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

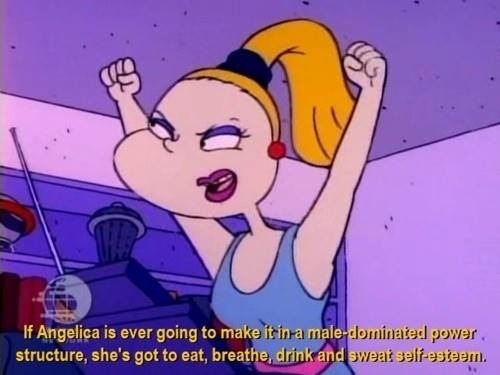

From a Riot Grrrl-era zine from early 1990s…

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The potential for increased accessibility in digital spaces is highly important, and not dissimilar to the ‘do it yourself’ ethos of the Riot Grrrl movement. Provided one has access to social media, which according to a 2016 Ofcom report, a staggering 99% of British 16-24 year olds do; anyone can make a page on Tumblr, anyone can create an Instagram account, anyone can curate. Riot Grrrl was an identifiable faction of the overall punk subculture, evident in its use of gritty visual qualities and the sense of urgency embedded in its narrative. Although it is easy to proclaim that the notion of the subculture has expired, I would like to argue that it is in fact as relevant as ever, despite no longer acting as a solace for those looking to rebel against the mainstream. Instead, the mainstream has morphed into a conglomerate of established cultures through the effortless connectivity of young people worldwide. In the same way that ‘the act of zine construction, of creating a multimedia, self-reflexively composed narrative, constitutes a strategy of identity construction’ (Spiers, 2015: 12), platforms such as Tumblr provide a new platform for self-expression from which teenagers can display their interests, though through images of objects and works of art as opposed to more traditional signifiers such as taste in clothing and music.

0 notes

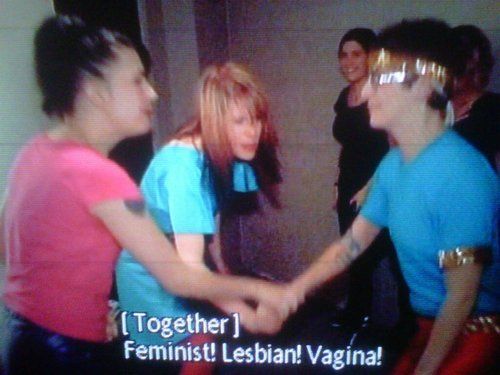

Photo

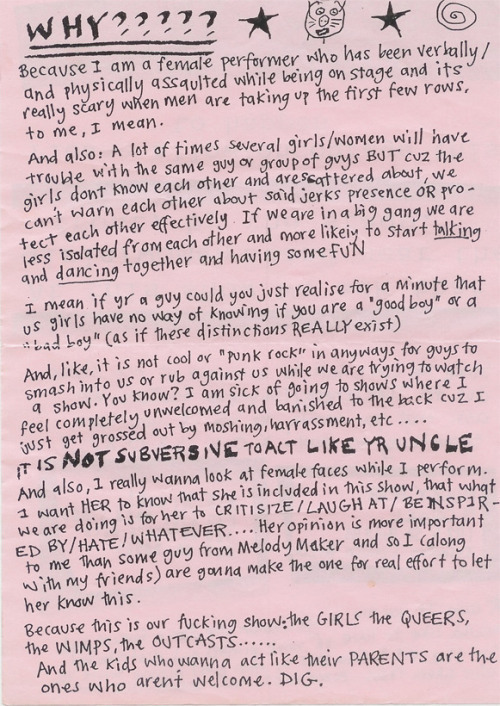

Flyer from Bikini Kill / Huggy Bear show

1992 / 1993

source: unknown

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Instead, I commend Jacotey for her use of the blog as a tool to deconstruct the traditionally elitist notion of ‘the artist’. She displays her work on Tumblr, in the typical blog format of reverse chronology, connoting a new genre of ‘fast art’ ready for consumption at the speed of which it is created. This particular platform promotes accessibility and the sharing of work, and the website’s ‘ask button’ allows easy communication between the artist and their audience. The utilisation of these components when presenting artwork confuses the preconception of the artist as an untouchable presence, and this format can serve as a digital alternative to the zine through its advocacy of inclusion and solidarity between creator and audience. As shown on the cover of the first issue of the Riot Grrrl newsletter (figure 2), the founders held a keen emphasis on rapid expansion of the movement, and readers were encouraged to set up publications all over the United States. The production of these zines, as Spiers notes, can be construed as a form of conscious self portraiture: “zines and other riot grrrl productions do not merely constitute a kind of therapy, but provide a forum for creative self-expression in narrative form” (Spiers, 2015: 12). It is for this reason that I have chosen to display my research through a Tumblr blog, as I believe this method to be the best visual representation of the main crux of this essay. Producing my own zine could have also be considered appropriate, however it is arguable that the Tumblr portfolio is a more appropriate platform in terms of audience reach in the current digital climate, due to the ‘reblog’ function now being much more accessible than a photocopier.

0 notes

Photo

Courtney Kissing Amanda de Cadenet at the Oscar Party 1995

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sleater-Kinney, pictured on the back cover of Dig Me Out | photo by Robert Paul Maxwell | via last.fm

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

However, the two examples still demonstrate clear differences, mainly due to their respective contexts. In the 1990s, Riot Grrrl was very much symptomatic of a subculture, trivialised by news outlets for its mix of ‘idealism and disillusionment’, with its revolutionary dialect being downplayed as childlike naivety bound to ‘evaporate when it hits the adult real world’ (Chideya et al., 1992). More recently, the now prime minister wears a T-shirt emblazoned with the phrase ‘this is what a feminist looks like’ (as shown in figure 3). The current trend regarding feminism, especially while it operates under capitalism, provides a new arena for critique. While Riot Grrrl remained ideologically opposed to capitalism and consumer culture (Spiers, 2015: 14), we now find ourselves in a world where female empowerment is marketed as a ‘lifestyle brand’ (Spiers, 2015: 17), in efforts to heighten corporate capital. It is on this basis that the following argument arises: can contemporary feminist creatives really be considered anywhere near as subversive as those who came before them?

0 notes