Photo

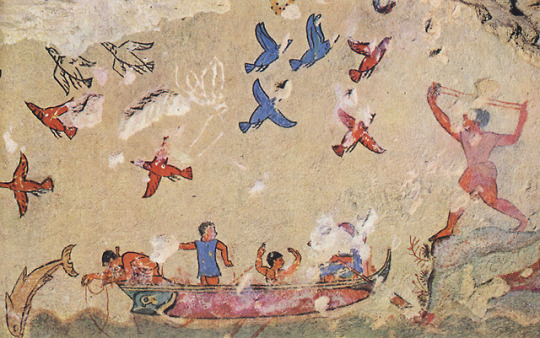

Tarquinia is an old city in the province of Viterbo, a region also called Tuscia, known for its outstanding and unique ancient Etruscan tombs in the widespread cemeteries which it overlies. The tombs expose magnificent and mysterious frescos, one of which, coming from the Tomb of hunting and fishing, is reproduced above. M. C. Escher visited Tarquinia in 1927. Around two decades later he started to draw his famous continuous patterns with animals and fishes, like the three reproduced here. I like to imagine Escher being inspired by the Etruscan reminisces from his youth for his own graphic style. The birds look alike, and fly in the opposite directions in both cases. Don’t you spot a connection?

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

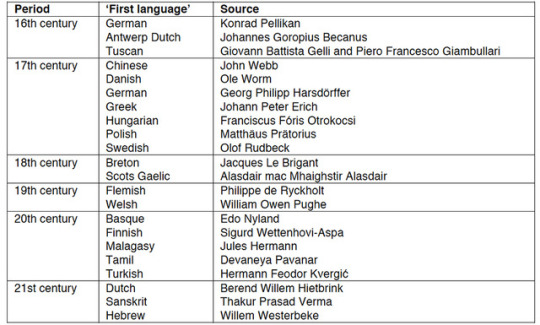

«Christian Europe used to consider Hebrew as the language of Adam and Eve, the first humans. But after the Middle Ages, many alternatives were suggested. This is an incomplete list of ‘first languages’»

https://aeon.co/…/why-is-linguistics-such-a-magnet-for-dile…

Apparently, Dutch (with Flamish) wins the race.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

National deixis, or: when does “France” become “Orient” in translation?

The situation when an author makes reference, in a text, to his/her own nation or country, or to his/her language, or history, can be considered an example of a deictic word usage. Indeed, the notion of “my country” — not unlike the notion of “self” — shifts from one referent to another when the speaker changes. Let’s call this phenomenon national deixis. This kind of context may represent a problem for a translator, and has been often debated in the field of Translation Studies.

How should we translate a passage when the author says something like “I love the hugeness of our country and the sound of its tonal language”? Most likely, we would translate the text word by word and then add something like “(the author is referring to China, editor’s note)”. Because, the author knows what his country is, but the reader could also be unaware of it. The only use of the possessive deictic pronoun our explains nothing, since the word our uttered by the author does necessarily refer to something different with respect to when it is uttered in the target language of translation.

Someone in the past used to translate national-deictic concepts substituting them with the corresponding expressions describing the nation, history and language of the speakers of the target language of translation. Robert M. Adams, in Proteus, His Lies, His Truth (1972), famously warns us against this attitude and states that, while translating a text from, say, French to English,

“Paris cannot be London or New York, it must be Paris; our hero must be Pierre, not Peter; he must drink an aperitif, not a cocktail; smoke Gauloises, not Kents; and walk down the rue du Bac, not Back Street”.

I wonder, by the way, whether he was, or was not, aware of a very similar passage in Eugène Ionesco’s absurdist comedy La Leçon (1951):

“Pour le mot Italie, en français nous avons le mot France qui en est la traduction exacte. Ma patrie est la France. Et France en oriental: Orient! Ma patrie est l’Orient. Et Orient en portugais: Portugal! L’expression orientale: ma patrie est l’Orient se traduit donc de cette façon en portugais: ma patrie est le Portugal".

But, as is often the case, the reality admits some exceptions. Recently I came across a nice example of this same translational attitude, which, far from being ridicule, sounded perfectly appropriate. In his book on the Goths and the Gothic language (1964), the Italian linguist Piergiuseppe Scardigli compares the remoteness of the Gothic kingdoms for the point of view of the 9th cent. Carolingian scribes to the equal remoteness of the Spanish domination in Italy, for the modern Italians:

“[…] nel IX secolo […] il regno di Teoderico era un ricordo tanto lontano quanto è per noi il ricordo della dominazione spagnola in Italia nel XVII secolo”.

This is a typical instance of national deixis: the author says “we” and makes reference to the history of his own country. Now, in the German 1973 translation of this book, the translator has tacitly substituted “Italy” with “Germany” and the historical fact of Spanish domination with the equally remote Thirty Years’ War:

“[…] im 9.–10. Jh. […] das Reich Theoderichs schon so lange der Vergangenheit angehörte wie für uns die Anwesenheit Gustav Adolfs auf deutschem Boden während des Dreißigjährigen Kriegs”.

0 notes

Text

Distanza lessicale tra lingue

Gira per internet un’accattivante infografica che presenta la cosiddetta distanza lessicale tra le varie lingue d’Europa. La metodologia non è specificata, ma viene fatto un vago riferimento all’articolo di F. Petroni e M. Serva, due fisici evidentemente appassionati di linguistica matematica ed NLP. Presumendo che l’infografica si basa su un qualche ragionamento analogo, propongo un po’ di pensieri critici.

La metodologia di Petroni e Serva si riduce, in ultima analisi, al calcolo della distanza di Levenshtein tra coppie di parole aventi lo stesso significato, provenienti da liste di 100 parole prese da ogni lingua in esame.

L'articolo contiene la seguente affermazione:

Indeed, our method for computing distances is a very simple operation, that does not need any specific linguistic knowledge and requires a minimum of computing time.

Che le conoscenze linguistiche non siano necessarie è, però, un'illusione (e non lo dico per difendere la categoria).

Un primo inghippo si nasconde nel concetto di "parole con lo stesso significato". In realtà, tali parole, cioè perfetti "translational equivalents" semplicemente non esistono. Ogni parola italiana viene tradotta non con una, ma con tante parole inglesi diverse, secondo il contesto, la sfumatura stilistica, ecc.; lo stesso capita per qualsiasi altra coppia di lingue. (Si veda un esempio banale: le possibili traduzioni del verbo italiano andare in inglese). Quindi la scelta di come riempire le liste di parole sulle quali si basa la misurazione è estremamente arbitraria e può trasformarsi in un bias capace di falsare il risultato. Ad esempio, in inglese esistono numerosi doppioni lessicali di tipo "Germanic vs. Latinate". Basta selezionare, per ogni significato, il termine "latinate", ed ecco che la distanza tra ENG e FRA diminuirà miracolosamente, ma indebitamente. Stessa operazione può essere fatta in molti altri casi (ad esempio, in russo esiste un vasto strato di doppioni lessicali di origine europea che affiancano parole di origine slava).

Secondo problema si nasconde nell'idea di confrontare la forma ortografica delle parole. Come sappiamo, le ortografie sono spesso arbitrarie, convenzionali e modificate a posteriori. Gli autori, probabilmente, avrebbero dovuto operare con una trascrizione fonetica normalizzata delle parole di ogni lingua, anziché con la forma ortografica: le due sono spesso talmente diverse l'una dall'altra da poter influenzare in modo significativo il calcolo finale.

Infine, la mancanza di “specific linguistic knowledge” impedisce agli autori di capire il fatto che questa loro "distanza lessicale" in realtà non è correlata con alcunché di scientificamente sensato. È come se dicessimo: classifichiamo le automobili per colore. Scopriremo magari che le macchine scure sono più performanti (perché, ad esempio, le macchine costose tedesche magari sono tendenzialmente di colore scuro). Però in realtà non è una misurazione scientificamente interessante. La distanza lessicale, analogamente, non misura un bel niente, perché gli autori non sanno cosa vanno cercando. Se si vuole ottenere una misura della distanza genetica, allora la "somiglianza" lessicale è un metodo totalmente sbagliato, che semmai impedisce di vedere le relazioni genetiche (le quali si basano sulle corrispondenze fonologiche regolari, non su somiglianze, come è noto a tutti i linguisti storici già da due secoli). Se invece si vuole misurare il numero di prestiti alloglotti in ogni data lingua, allora il calcolo è sbagliato in partenza, perché, appunto, non fa alcuna distinzione tra parole imparentate e quelle di prestito.

Come spesso accade in questi casi, la rappresentazione risultante, in ultima analisi, è molto poco informativa: non dice nulla che non sapessimo già (ossia che le lingue all'interno di un gruppo linguistico, ad esempio quello germanico, si assomigliano maggiormente che con quelle di altri gruppi). Va dato atto a Petroni e Serva: le loro conclusioni sono effettivamente molto caute.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

When a genius gets insane…

The founder of modern linguistics, Ferdinand de Saussure, at the end of his life, devoted himself to a rather strange research program concerning the presumed “anagrams” in ancient and — as we see here — modern poetry in Indo-European languages. Particularly, here he asks the Italian poet Pascoli about the possibility that some Latin words were encrypted as anagrams in his Latin poems.

…he is still a genius

Saussure was well aware of the fact that all this theory was far from being convincing and needed to be supported by some good evidence. With such respect, let us see the last page of the letter, where he makes a brilliant observation, almost a methodology lesson, on the role of statistics in the linguistic investigation:

“[…] plus le nombre des exemples devient considérable, plus il y a lieu de penser que c’est le jeu naturel des chances sur les 24 lettres de l’alphabet qui doit produire ces coïncidences quasi-régulièrement”

Which means: the anagrams are likely to happen casually, so, if there are too many of them, the chance should be considered the most appropriate explanation. Therefore, in order to exclude the chance, he decided to make an enquiry directly to the author about his intentions.

Pascoli’s answer is not known.

Saussure’s letters have been published online here.

Saussure’s researches on anagrams have been collected and analyzed here.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two boys from Guinea...

In 1989 Abdoulaye Barry and Ibrahima Barry, two brothers from Guinea of 14 and 10 years of age respectively, asked their father why they could not write their language, and when their father wrote a few words in Fulani in Arabic script, they said “That’s not our script. We should have our own”. Then the two boys decided to devise a new alphabet for their language. Not unlike millions of boys do all over the world, at that age. With the difference that their creation — the Adlam alphabet — was successful. Over the next few years the Adlam script continued its development. It is currently in use in Guinea (where it is taught in schools), as well as in other countries, and its use is increasing.

This is how the two brothers, now adults, tell the story themselves.

Here is a PDF with a handbook that teaches the script, in Fulani language.

(Note how the typical ABC pictures — mnemonically representing the letters by which the corresponding words begin — reflect a contemporary African reality.)

42 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Lees maar, er staat niet wat er staat

Martinus Nijhoff

0 notes