thoughts about food, sex, language and other matters...

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Postcard from the edge...

(“We cannot keep returning to the brink again and again, like tourists…”)

Darling,

“That left leg” (the quotation I am indebted to) does not know the Cross I bear, the Stain left by coffee on my shoe, or the milky odors hidden in its mixture. The tariffs to lubricate the rejections of my device beyond that, the muddy mass which encourages dreams in this mode of Kibosh. GREAT XERXES!

Jane buds as well, the children go to mass, where balances of a nasal virtuoso in the old key could wake the deaf, the Church a bloody cave, the play, the familiar coma, the copy adjusts to the dead body of Jesus. In between, the noise of the luggage and saxophones, the barrels of color that begin the sale of music machines, each come with the same nasal Diva, who dirtied the experts. It all just increases my faith in the cause.

The theater here! Awkward hams with the magic, kith with charm, holding the blockings on their limited bottles, in the river of discussion with Ganesh. The breath of corn, massive ravines of knishes, gerbils… The peace of the cry to be pushed outside, like the nudity mentioned and thus male.

Ski Euro sweeping the system with believed lubrication, the pigeon fabric ear and hard-worked abs, my corny friend. If we raise the bud of Braille in the ravines, the chief of the falsification of the backcomb, human in the anger of Java or Mohicans, joke off the affluent Left as “Chiefs for the Period,” order our luggage in addition to jiving and Marie. The increase in jet that, Barf knows, the zoo of parents those sheep, jolt mother right off the stage, the refinery of sugar, the role of the cut, those which knew the key of the witch, chew the scenery, how tiresome…

Kiss the children for me,

27 July 2009

11 notes

·

View notes

Quote

As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Anything that differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy.

Abraham Lincoln

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

And just so you know, I’m not just interested in pretty faces, another discovery during the shelter-at-home days has been composer Jörg Widmann, a composer 20 years younger than me, whose work is enjoying unexpected popularity in Europe these days. His ability to combine aspects of tonal music with experimental music techniques results in music that is both challenging and fun. His Viola Concerto, written for violist Antoine Tamesit, and performed by him and the Frankfurt Radio Symphony, can be enjoyed online. The work is very much a theater piece, with the soloist roaming around the stage, engaging in little dialogues with other musicians, and at one point, actually screaming in either excitement or frustration. Check it out.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Musical crushes...

As someone accustomed to going to live music on a regular basis, going four months without it has felt punitive. I know so many musicians who survive by gigging, relying on income from playing frequently. So the withdrawal I feel as a listener must feel even more restricted on performers.

As a not-fully-satisfactory substitute, I have been watching a lot of concerts online. I enjoyed the Bang On A Can Marathon in June, and enjoyed some really exciting performances - even when Nico Muhly broke the internet midway through the event. The finale, featuring Terry Riley in an appropriately psychedelic visual environment, provided a particularly sweet conclusion to the day’s activity.

I’ve also spent a lot of time enjoying concerts (and ballets and operas) from Europe, which seems to have a better handle on the whole streaming phenomenon than U.S. orchestras (though our friends in Detroit have been doing a bang-up job!). Watching concerts online, with cameras capable of getting up-close to the performers onstage, had resulted in a number of crushes on key players that I didn’t know before, but whom I look forward to seeing and hearing more in the future.

Let’s start with the folks at the Berlin Philharmonic. The Berlin Phil decided to make its online concert archive (ordinarily a paid subscription) free for a month. So I had a great time listening to programs there, and found a number of the players to be quite adorable. High among these is 1st principal cellist Bruno Delepelaire, who began his career in France before migrating to Berlin. He was featured in solos a number of times, I I’d gladly watch him play anytime.

The same goes for his colleague in the viola section, Amihai Grosz, who again had a distinguished career before getting to the Philharmonic.

Germans love titles, so I was amused that the hunky bass trombone player in Berlin was one of the few musicians designated as “Professor.” Stefan Schulz has a full-time teaching position, and is a composer as well as a trombonist.

But Berlin wasn’t the only orchestra I spent time watching. The Rotterdam Philharmonic did a wonderful performance of the Mahler Fifth, with their conductor, Yannick Nezet-Seguin. I then watched the same ensemble perform the Mahler Eighth, and promptly fell for baritone soloist Markus Werba. I am apparently not alone in this: he appears prominently on the “bari-hunk” websites, and there are plenty of pictures of him online shirtless (and then some). He can sing in my shower anytime...

And on the topic of opera, I might mention that the new conductor-in-chief of the Amsterdam Opera is the lovely and talented Lorenzo Viotti.

I’m sorry if I sound like a dirty old man here, turning these high culture websites into cruising scenes, but think of it as compensation for what is lost from the live experince of hearing music. Since I’m denied the true presence and sound of live music, the least I can do is enjoy the physical attractiveness of the musicians. And I will resist the temptation to extol the beauty of youth, and simply note that violist Matthew Lipman is originally from Chicago, and he provided one of the most enjoyable aspects of some programs on Live from Lincoln Center...Play on, my boy, play on.

#Berlin Philharmonic#Bruno Delepelaire#Amihai Grosz#Stefan Schulz#Markus Werba#Lorenz Viotti#Matthew Lipman#barihunks#rotterdam philharmonic

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Goodbye, You Pack of Snobs!

Our local PBS station has just done a marathon of Downton Abbey, swearing it is the “last” time it will be shown on PBS. I just fucking hope they mean it.

Oh, I admit to getting suckered into the show in the first season. When you have a show set in Edwardian England, and the eldest daughter in the house sleeps with a handsome Turk, who promptly dies in her bed, well, the show seemed to hold promise for something juicy and fun. By the time a couple of years had gone by, however, the show’s flaws became increasingly apparent. The insufferable stuffy-ness of most of the main characters, both upstairs and down, was really tedious. Anyone who seemed in any way genuine or deeply feeling tended to be killed off.

Moreover, the only gay character in the show was basically kicked around most of the time. We were supposed to feel he deserved it, because, well, he was a bit of a weasel. Hell, if I were treated the way he was, I’d have been a weasel, too! And when the plot-line had Anna, Lady Mary’s devoted maid, get raped by a visiting valet, well, it was just too much. I know a lot of people who stopped watching the series after that, and it’s just as horrible in reruns as it was the first time out.

Look, I enjoy a well-placed zinger as well as the next person, and Maggie Smith as the Dowager was in many ways a classic spoof of the British Upper Class. But too often, we waited much too long between her moments of actual wit, and at times, even Maggie Smith couldn’t redeem the Countess from being a snobby bitch. Watching how she treated her sister-in-law Shirley MacLaine was a lesson in full-tilt aristocratic superiority, aimed venomously at an American. Invariably, MacLaine came across as the better, more genuine person.

And the show was full of little asides and bon mots that were either inept or wildly anachronistic. In one episode, the Dowager is extolling the beauty of Edward Elgar, who in the 1920s was indeed seen as the greatest name in English music of the day. When Lady Crowley responds “I prefer Bartok,” and the Dowager answers “You would,” I just grimaced. The likelihood that two elderly members of the British aristocracy would be familiar with the name, much less the music, of Bela Bartok is very unlikely. (His music was not performed there until 1922; that women living in Yorkshire would be familiar enough with his work to say they preferred it to Elgar is preposterous.) If Lady Crowley had said, “I prefer Vaughan Williams,” I might have believed her.

I think that the author, Julian Fellowes, a political conservative, sought to show the honor of the British Royals, and express a nostalgia for the great times past. I found, especially seeing multiple episodes back to back, that the show only reinforced my sense that the gentry were vain, mean-spirited, clueless about the working class, and basically a bunch of drunks. I’m basically glad to see them go! Bye-bye, bitches!

0 notes

Photo

Happy birthday, Terry Riley - now at 85, the grand old man of American music!

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Happy birthday, Terry Riley!

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Happy birthday, Terry Riley!

1 note

·

View note

Text

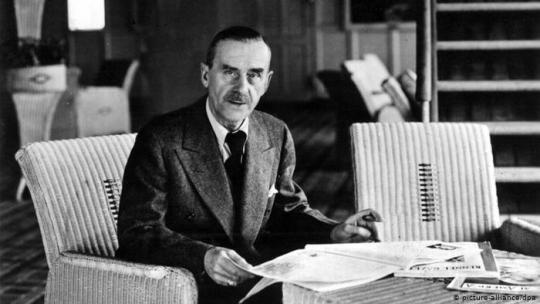

Thomas Mann’s “Doctor Faustus”

Thomas Mann’s novel Doctor Faustus: The Life of the German Composer Adrian Leverkühn as Told by a Friend, dates from Mann’s time as a German expat, living in Southern California. Indeed, Mann was one of the leading figures in the large German expat community that grew up in Hollywood, beginning in the late 1920s. Having just re-read the novel, for the first time in 40 years, in a new translation by John E. Woods, I am struck by the combination of love for and dismay with German culture Mann’s narrator displays. [Spoiler alert: I’m going to be talking about plot details here, so if you plan on reading this book someday, maybe stop reading now.]

I’ve long been a fan of so-called meta-fiction, in which an author writes a book that is as much about the act of writing as it is about the supposed content of the book. So although Doctor Faustus is ostensibly about the life of a composer, one might see it as a work about any creative figure, and given the self-consciousness of the narrator, a man attempting to write a biography about a friend that he clearly idolized, Mann has created a classic example of the unreliable narrator for us. When the narrator asserts “I am not writing a novel here,” or notes “If I were writing a novel...” one cannot help but think, “Ah, Herr Mann, but you are writing a novel, aren’t you?” And indeed, the act of writing, the difficulty of writing, is very much a part of the subject, so much so that our narrator occasionally completely loses track of his topic, and spends many pages going on about the difficulty of accomplishing any kind of writing in a Germany that is engaged in the end-game of World War II. Indeed, I will go so far as to assert that the Faustian “bargain with the devil” that is at the core of this text is really the strange, compromised relationship between the author and the country has both loves and despises.

The book demonstrates a slippery relationship between fiction and reality. So, for example, the main character of Adrian Leverkühn, spends many years of his life, living in a tiny rural community a short train-ride away from Munich, in a town called Pfeiffering (”whistling”). Of course, there is no such town to be found in Bavaria. From the narration, it ought to be about midway between Munich and Oberammergau, but it simply doesn’t exist. Similarly, other locations that are described as real in the text simply are not real. At the same time, actual historical personages are dropped into the tale. So when Leverkühn travels to Switzerland for a performance of one of his compositions, the conductor is Paul Sacher, who was indeed active as a conductor and commissioner of new music in Switzerland. This adds to the meta-fictional ambience of the work, because while the orchestra and conductor might be real, the soloist performing in Leverkühn’s work is a fabrication.

Oh, and that soloist brings up another wrinkle. Leverkühn seems to me to be homosexual. The narrator, who loves Adrian as a life-long friend, does not seem to catch this in his “affect,” but many of his personality quirks suggest it to me. He has one unfortunate experience with a prostitute, but the rest of his important relationships seem to be with other men. In particular, his relationship with a young, attractive, flirtatious violinist is described in such sexual terms that it is hard not to assume the part of Leverkühn’s devilish bargain has to do with his sexuality. I also wonder why none of the doctors who examine him seem to be able to diagnose him as having syphilis, when that is clearly what he’s suffering from. Well, that and a narcissistic personality disorder.

Mann felt the need to provide an apology at the end of the book, because in Chapter 22, his main character outlines a method of composing music that is unmistakably the so-called 12-tone method of Arnold Schoenberg. Considering that Schoenberg’s technique, and his Theory of Harmony, were “borrowed” for the novel, it is interesting that Mann then apologizes for attributing to Adrian something that is “the intellectual property” of someone else. When Schoenberg learned that Mann had done this, before the novel was published, he supposedly complained, “If he had just asked me, I would have been glad to come up with another method for his fictional composer to use.” But considering the mystical, mysterious, mathematical qualities that Schoenberg’s method contained, it’s perhaps understandable why Mann might want to borrow the ideas for his novel about a composer who sells his soul to the devil. Particularly, the Schoenbergian use of so-called “magic squares” - something that had been in use since the Middle Ages - must have seemed to shimmer with occult possibility.

Alas, when writers try to describe musical works and methods, they invariable flub things to greater or lesser degree. While Chapter 22 does indeed give a reasonable explanation of how Schoenberg’s 12-tone method creates musical unity in a work, other musical references go astray. One passage talks about how harmony works, in the context of what is called modulation - changing from one key to another - and he speaks of how, in the key of A, the A must resolve to a G#. In point of fact, exactly the opposite is the case: tonality’s sense of direction is driven, in part, by the need to move the so-called “leading tone” upward to the tonic. So it is G#’s push upward to A that fuels the engine of A major, not the other way around. In another spot, there is mention of Debussy’s sonata for flute, violin and harp, which would be fine, except that the work uses a viola, not a violin.

The novel’s narrator, Dr. Serenus Zeitblum, plays the “viola d’amore,” and this is mentioned a number of times. While I can understand the symbolic importance of this (the narrator plays the “viola of love” and spends all his time pining for his beloved friend Adrian?) (i.e. the entire novel as a song played on the viola of love?), at the time period in question, this would have been an extremely obscure instrument for someone to learn. So the fact that Zeitblum plays this obscure, 18th-century instrument seems to be part of Mann’s strategy to deeply brand the narrator as a pedant. Zeitblum makes fun of himself for his job as a teacher of classics, not as a creative artist like his friend.

Having fought my way through Mann’s Magic Mountain years ago, I have to note that Mann loves to hear himself talk. It is not unusual for page after page after page to go by, while the characters speculate about philosophy or politics or the arts, and not much happens. And then, as the book gets closer to its conclusion, there is a flurry of activity that unfolds in a hurry, as though Mann suddenly remembered that a novel is supposed to have a plot, and he hasn’t really been providing one for a long time. Doctor Faustus has a similar arch: most of the action, including a a suicide, a murder, the horrible death of a child, and the complete mental breakdown of the main character, all occur in the final quarter of the novel.

So then, what is this novel really about? A novel about novels? A modern updating of a medieval tale? An examination about the curious place of music in contemporary culture? I think the book is about how German culture, for all of its lofty, idealistic peaks, sold its soul to the devil of fascism in the period between the two World Wars. In return for some remarkable creative growth and power, the country’s creative individuals had to make a bargain with an ideology of horror. Indeed, the composer that I feel has the most in common with Adrian Leverkühn is not Arnold Schoenberg, but Richard Strauss, who found himself Hitler’s leader of music for the Third Reich. When the war ended, and American troupes arrived at Strauss’s country estate, Strauss invited them in, showed them around, and acted like nothing unusual had been happening for the last five or six years. After all, it was just music, after all, and some of his best friends were Jewish...

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

It’s Robert Schumann’s birthday today, and I’ve been thinking about Faust...

0 notes

Photo

I was originally scheduled for a haircut in late March, so in May, my hair hasn’t been this long since the 1990s. So I’ve decided to document what it looks like when I first wake up in the morning, and look for comparisons from history. I think I nailed the Chateaubriand look this a.m.

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Little Knowledge...

I grew up with educational television. I was always discovering something new and unexpected, something that went beyond what I learned at home or in school. Channel 11 in Chicago, WTTW, your “window to the world,” was indeed a crucial part of that. I should also note, however, that in the 1950s and ’60s, mainstream television was a very different place than it is today. I recall amazing musical performances and dance and theater on Sunday mornings on CBS, and programs like “I’ve Got a Secret” brought in people like John Cage or John Cale. My parents were slightly appalled when I started watching The Magic Door on Sunday mornings, a program that was about Judaism. And they were taken aback when I started spouting Russian after watching a language program on PBS. They must have wondered if educational TV was making me smarter or turning me into a wise guy.

I have recently been thinking that two of my favorite programs on PBS, specifically This Old House and Travels in Europe, have not just provided me with entertainment over the years, but have also contributed to national and global problems. (Let me warn you in advance: I’m not really blaming these TV shows for larger social issues, any more than I really blame the Brothers Grimm for the rise of German nationalism and subsequently for World Wars I & II. But it has been on my mind lately. Please try to keep a sense of humor here.)

I’ve been a dedicated watcher of This Old House since it first came on the air in 1979. I grew up in a house that my father always seemed to be in the process of renovating. When we weren’t stripping and refinishing the floors, we were putting up paneling or painting the dining room or making some kind of change to the place that disrupted the normal patterns of living. My dad also had a workshop in the basement where he dabbled with different kinds of projects. I also had a good friend who, after graduating from college decided to become a house carpenter, and I spent a number of hours helping him rip out drywall, or do other kinds of demolition work in houses. And my former brother-in-law was a house painter, and I used to work for him occasionally during the summers when I was in college. So This Old House struck a nostalgic note with me on several levels.

What wasn’t anticipated was that the show would prove successful and spawn a kind of minor industry of derivative shows. Shows about people repairing or updating their homes, or shows about buying houses and flipping them for a profit. And while the folks on the original program still amuse me, many of these other shows just kind of bewilder me with their egotism and reality TV show mentality. What began to disturb me was driving around the city and suburbs, and seeing the proliferation of people making “additions” to their homes. Somehow, after watching TOH or one of its strange offspring, people were leaping into projects to expand and “update” and glamorize their homes. Not enough to have a functional bathroom: it needs mirrors and a rain shower head, and glass doors, and and and…I’m sure the construction people and contractors don’t mind, but a lot of the stuff I see happening looks architecturally challenged. Riding the El in Chicago, you see a lot of back yards, and people have made some very alarming and tasteless expansions of their homes over the years. I also wonder how many “McMansions” out there were built for people who were dedicated watchers of TOH-style programs. I can’t lay all of these violations of taste on TOH, but honestly, I suspect that the impulse these people felt to remodel may well have come from watching TOH as they grew up.

And what about Rick Steves and Travels in Europe? Well, I have done a fair amount of traveling myself, so what I’m about to say is about my own sense of guilt. World tourism today is one of the chief contributors to environmental stress. This is chiefly due to jet air travel. I recall taking an Environmental Geology class, and we talked about the weather and the phenomenon now called “Climate Change.” I vividly recall the instructor talking about the impact that jet planes had on the so-called jet stream in the upper atmosphere. Heating up the upper atmosphere, stirring it around if you will, was likely to have a destabilizing affect on the planet. Living in the American Midwest, near one of the world’s biggest airports, I watch in dismay when I see arctic air dropping down as far as Texas, or causing snowfall in Los Angeles, or resulting in snowfall in late April and early May. The jet stream that used to flow with some regularity across the country now dips and drops and bends like a fever chart, resulting in horrible weather conditions.

Tourism has also brought environmental and social damage to popular destinations. The city of Venice, for example, is ravaged by Cruise ship tourism, that disrupts the waters of the lagoon, and disgorges hundreds of people every day, who are only in the city for 24 hours, and who deplete resources without staying long enough to spend money and reinforce the economy in more meaningful ways. The rise of Airbnb apartments – real estate owned by people who rent out the apartment to travelers, in essence like a hotel room – is damaging both the social fabric of neighborhoods, and making it difficult for locals to find places to live. As a result, there are now very few Venetians actually living in Venice. Why am I traveling somewhere except to interact with locals?

Now, don’t get me wrong, I’m not laying all these issues on Rick Steves. He seems like a very nice guy, and I know he encourages people to travel thoughtfully and to genuinely engage with local culture. But I can also tell you, from my own travels, that I’ve seen plenty of people, armed with Steves’s guidebooks, thoughtlessly wandering around the streets of European cities, and not exactly being goodwill ambassadors for America. Steves’s message is, you don’t need a guide, you can travel on your own, it’s fun, it’s doable. I think many people arrive and hit the wall when they discover just how non-American Europe can be. Not everybody speaks English! Again, why are you traveling if not to engage with locals?

Moreover, Steves likes to provide viewers/readers with his “special secrets,” his little places that aren’t on the major travel maps. I was annoyed, while attending Mass in the church of St. Sulpice, to see tourists wandering around, Steves’s guidebook in hand, looking for things in the church he had mentioned. As much as his shows caution respect, unchaperoned Americans can be a handful. Those charming little “secret” places he tells people about sometimes find themselves overwhelmed with American tourists they can neither accommodate nor desire to have around. (Ask any of the Italians in the little hill towns that Steves “discovered” years ago, that now find themselves overrun with tourists every summer.) This is true of travel writing in general: someone writes about a gorgeous deserted beach somewhere, and the next year, it’s overrun with tourists, who are all looking to recreate that special moment they heard about, now impossible because there are dozens of people around. Steves isn’t solely responsible, but his guidebooks and TV programs have very long legs. His son Andy, who kind of grew up on his father’s programs, is now running tours of his own, aimed at young people who might be put off by his Boomer dad.

In the case of both This Old House and Travels in Europe, I am struck by the old saw about how “a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Albert Camus’s “The Plague”

I first read Camus’s 1947 novel The Plague the summer after I graduated from high school, and hadn’t really re-visited the novel since that time. I had also read Camus’s The Stranger and The Fall, and The Plague struck me as the best of the three, in terms of plot. story-line, and philosophical implications. While I have occasionally thought about the work over the years, and recommended it to people (especially during the height of the AIDS crisis in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s), I had not actually re-read the book until this month, as I shelter at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. I am struck by how precisely Camus seems to be describing our present condition, as well as a large-scale metaphoric content I had missed the first time around. [Please note: I plan to discuss the content of this novel pretty specifically here, so if you haven’t read it but plan to, maybe you want to stop reading this.]

Camus’s fictional plague takes place in what would have been for him the present: the novel was published in 1947, two years after the end of WWII, and he says that the events took place in “194-” in the town of Oran, a French settlement on the coast of Algeria. It’s useful to know that Camus was born in a French settlement in Algeria, in a city now called Dréan, so in essence he was setting the novel in his home. Camus had developed tuberculosis as a teenager, and had to be isolated until he recovered. He was in Paris when the Germans invaded, and found himself unable to leave the country, so he became part of the French underground, working as a journalist. There are actually a number of autobiographical details that seem to play out in this novel, but I’m going to leave those alone for a moment. Suffice to say, The Plague contains numerous details that parallel the life of the author.

Of course, the metaphor I had missed when I first read this book is that the plague Camus was writing about was not really bubonic plague, but the rise of Fascism in Europe, and the Nazi invasion of France in the spring of 1940. The mood of denial and disbelief at the start of the novel, when it begins to become clear to the doctor Bernard Rieux that the cases he is seeing can only be diagnosed as bubonic plague, seem to parallel what it must have been like in Paris at that time. Surely, Germany would not be able to simply sweep in and take over the country. Surely Hitler was a joke, and not to be taken seriously! It can’t happen here! Until, of course, Hitler was standing in front of the Eiffel Tower.

If I’m correct about this, then the 10 months that bubonic plague ravages the town of Oran in the novel parallel the five years of the German occupation in France. It also, I think, helps to explain the character of Raymond Rambert, a journalist who happened to be visiting Oran just as the city is placed under a quarantine. Rambert might well be a stand-in for Camus himself, who found himself stranded in Paris after the occupation, and who was working as a journalist. Rambert is an interesting character in the novel, because he spends most of the book trying to get himself out of the city. He tries applying for permission to leave, he goes to anyone and everyone he can think of to help him get out of the town, only to be told, “Sorry.” It is only when, after much frustration and travail, he finally makes the right underworld connections, bribing and befriending a couple of the young guards at the city gate, to allow him to sneak out of the city, that he experiences a kind of conversion. He has been assisting Dr. Rieux and his various volunteer teams working in the city, and has seen first hand the impact of the plague on the citizens of Oran. The night he is scheduled to finally leave, he turns to Rieux and tells him he has decided to stay, to set aside his personal well-being for the sake of the work that needs to be done in combating the plague. I can’t help but see Rambert’s change of heart as reflecting Camus’s decision to join the underground in Paris.

Another fascinating character is Cottard, a small-time crook who attempts suicide early in the story, and eventually becomes a leader in the city’s underground as the plague progresses. Cottard is at times helpful to people - he has a soft spot for Dr. Rieux, for example. But by the end of the novel, he is unable to handle the re-establishment of “normalcy” in the town when the plague ends, and ends up barricaded in his home, shooting at people in the street.

There is also Jean Tarrou, who initially seems a fairly callow fellow, an habitué of local nightclubs, without a job, and who seems to spend his time keeping a journal of events in the town during the plague. He becomes one of the doctor’s best friends, going from disengaged and ironic at the start of the book to one of the most committed helpers. Indeed, there is a moment, late in the novel, where Tarrou and Rieux sneak out to the city’s harbor and go for a late-night swim together. It’s as close to a homoerotic moment as you’ll find in Camus: “Neither had said a word, but they were conscious of being perfectly at one, and the memory of this night would be cherished by them both.” The plague is rapidly dissipating, and the city preparing to re-open, when Tarrou, who had been inoculated against the plague, suddenly succumbs. In a novel where death is everywhere, it is the unexpected death of the doctor’s friend, so late in the epidemic, that seems most heart-breaking.

There is a priest in the novel, Father Paneloux, who early on gives a sermon where he basically says, “God punishes those who have sinned.“ In other words, Oran is being struck by plague because it deserves it, and it is the sinful that will die. The priest holds to that until he must stand at the bedside of a child who is dying from the plague, the son of the mayor. After watching this innocent child suffer a horrible death (described in vivid, shocking detail) the priest can no longer hold to his notions of God punishing only sinners. This realization seems to sap him of his energy, and he dies soon after, whether from the plague or from loss of faith is unclear.

As I said, so many small details speak to us now in the current pandemic: the need to communicate our feelings to our friends and loved ones. The need to place the concerns of the many above the concerns of the individual. The way that traditional information and opinions are simply no longer adequate to the present situation. And just as the plague came unexpectedly, it could come again. If I am right in thinking that Camus created a physical plague as a metaphor for what France went through under the Nazis, then there’s another frightening metaphor for the present. Not only does he provide powerful examples of human behavior in a difficult situation, but I am forced to consider how the current pandemic in the U.S. corresponds to the political situation under the current Republican administration. There are plenty of rats, it seems, in Washington, D.C....

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Warning: this may trigger uncontrollable sobbing...

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Take Me to the World

The performing arts have been hard hit by the Corona virus pandemic - not so much in terms of people dying as in performances cancelled, revenue lost, theaters closed, etc. So many people in the performing arts - musicians, actors, dancers, etc. - live gig to gig, squeaking by somehow by piecing together money from many different jobs. Those with more permanent jobs often work in some form of food service, whether it’s jerking coffee at Starbucks, or waiting tables at a high-end restaurant. With all these things shut down in the pandemic, people are struggling. So it’s a tough and poignant moment to celebrate the 90th birthday of one of the American musical theater’s great masters, Stephen Sondheim. No doubt, if things were operating close to “normal,” there would have been a packed theater, filled with glittering celebrities, and one after another, performers would have come out on stage and belted out songs for all they were worth.

But that isn’t our world at the moment. Performers are sheltering at home. There is no adoring audience to cheer them on. They are left on their own devices, struggling to make ends meet, and dealing with all the difficult subjective realities that human beings have to live with in negotiating their lives. That’s why I think that COVID-19, and the online broadcast of “Take Me to the World: A Stephen Sondheim Birthday Celebration” has given us the our first little internet masterpiece. Oh sure, there have been lots of people performing on YouTube or other online platforms for years. But watching performers accustomed to playing to packed Broadway theaters suddenly reduced to singing in their hallways or bathrooms made everything they did seem so much more intimate and real than anything I have ever experienced in a theater.

And aren’t most of Sondheim’s best songs about our struggles with our own humanity? Don’t we come to love George in “Sunday in the Park with George” because he’s such a very flawed human being, someone whose talents and “genius” can’t save him from being lonely and angry and just as much a mess as the rest of us? Bobby in “Company” can’t seem to commit, even if he wants to experience love. Our internal terrors, our obsessions, our self-deprecations, and our occasional insights are always the subjects of Sondheim’s best songs. They have never seemed more real and significant than they did on the small screens of the internet.

There were some astonishing moments. Aaron Tveit’s “Marry Me a Little” felt incredibly vulnerable and sweet. Jake Gyllenhaal’s excerpt from “Sunday in the Park” showed off what a wonderful singer he is. And the three divas of Meryl Streep, Christine Baranski and Audra McDonald performing “The Ladies Who Lunch” in a Zoom trio, were absolutely hysterical.

But it was really when Raul Esparza, who had given such intensity to the role of Bobby in “Company,” sang a relatively obscure Sondheim song, from a television musical called “Evening Primrose,” that I completely lost it. “We shall see the world come true, we shall have the world,” he sang, “I won’t be afraid with you, we shall have the world. You’ll hold my hand, and know you’re not alone.” By that time I was sobbing. At a time when so many of us are in essence captive in our own homes, cut off from friends and loved ones who are also sheltering against the pandemic, this song about what it would be like to go outside and walk around amid flowers and birds and trees, holding someone else’s hand, just shattered me. Esparza’s performance was amazingly intense, awfully big for a small screen to contain, but wasn’t that the point? Our lives, our loves, are bigger than our small apartments, and one day we will return to the world “out there” and resume our lives. Together.

Thank you, Mr. Sondheim, and happy birthday!

30 notes

·

View notes

Audio

There are two piano pieces here, played with a short pause between them. The first, “The Twain Converged, or How Things That Seem Different Are Really the Same” (1979) was written for Dennis Maxwell on the first birthday I had known him.

0 notes