Quote

The art of knowing is knowing what to ignore.

Rumi (via themedicalstate)

248 notes

·

View notes

Quote

To be a master is to forever be a student

Unknown (via mednerds)

211 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Your Vaccinated Immune System Is Ready for Breakthroughs

Getting COVID-19 when you’re vaccinated isn’t the same as getting COVID-19 when you’re unvaccinated.

A new dichotomy has begun dogging the pandemic discourse. With the rise of the über-transmissible Delta variant, experts are saying you’re either going to get vaccinated, or going to get the coronavirus.

For some people—a decent number of us, actually—it’s going to be both.

Coronavirus infections are happening among vaccinated people. They’re going to keep happening as long as the virus is with us, and we’re nowhere close to beating it. When a virus has so thoroughly infiltrated the human population, post-vaccination infections become an arithmetic inevitability. As much as we’d like to think otherwise, being vaccinated does not mean being done with SARS-CoV-2.

Post-vaccination infections, or breakthroughs, might occasionally turn symptomatic, but they aren’t shameful or aberrant. They also aren’t proof that the shots are failing. These cases are, on average, gentler and less symptomatic; faster-resolving, with less virus lingering—and, it appears, less likely to pass the pathogen on. The immunity offered by vaccines works in iterations and gradations, not absolutes. It does not make a person completely impervious to infection. It also does not evaporate when a few microbes breach a body’s barriers. A breakthrough, despite what it might seem, does not cause our defenses to crumble or even break; it does not erase the protection that’s already been built. Rather than setting up fragile and penetrable shields, vaccines reinforce the defenses we already have, so that we can encounter the virus safely and potentially build further upon that protection.

To understand the anatomy of a breakthrough case, it’s helpful to think of the human body as a castle. Deepta Bhattacharya, an immunologist at the University of Arizona, compares immunization to reinforcing such a stronghold against assault.

Without vaccination, the castle’s defenders have no idea an attack is coming. They might have stationed a few aggressive guard dogs outside, but these mutts aren’t terribly discerning: They’re the system’s innate defenders, fast-acting and brutal, but short-lived and woefully imprecise. They’ll sink their teeth into anything they don’t recognize, and are easily duped by stealthier invaders. If only quarrelsome canines stand between the virus and the castle’s treasures, that’s a pretty flimsy first line of defense. But it’s essentially the situation that many uninoculated people are in. Other fighters, who operate with more precision and punch—the body’s adaptive cells—will eventually be roused. Without prior warning, though, they’ll come out in full force only after a weeks-long delay, by which time the virus may have run roughshod over everything it can. At that point, the fight may, quite literally, be at a fever pitch, fueling worsening symptoms.

Vaccination completely rewrites the beginning, middle, and end of this story. COVID-19 shots act as confidential informants, who pass around intel on the pathogen within the castle walls. With that info, defensive cells can patrol the building’s borders, keeping an eye out for a now-familiar foe. When the virus attempts to force its way in, it will hit “backup layer after backup layer” of defense, Bhattacharya said.

Prepped by a vaccine, immune reinforcements will be marshaled to the fore much faster—within days of an invasion, sometimes much less. Adaptive cells called B cells, which produce antibodies, and T cells, which kill virus-infected cells, will have had time to study the pathogen’s features, and sharpen their weapons against it. While the guard dogs are pouncing, archers trained to recognize the virus will be shooting it down; the few microbes that make their way deeper inside will be gutted by sword-wielding assassins lurking in the shadows. “Each stage it has to get past takes a bigger chunk out” of the virus, Bhattacharya said. Even if a couple particles eke past every hurdle, their ranks are fewer, weaker, and less damaging.

In the best-case scenario, the virus might even be instantly sniped at by immune cells and antibodies, still amped up from the vaccine’s recent visit, preventing any infection from being established at all. But expecting this of our shots every time isn’t reasonable (and, in fact, wasn’t the goal set for any COVID-19 vaccine). Some people’s immune cells might have slow reflexes and keep their weapons holstered for too long; that will be especially true among the elderly and immunocompromised—their fighters will still rally, just to a lesser extent.

Changes on the virus side could tip the scales as well. Like invaders in disguise, wily variants might evade detection by certain antibodies. Even readily recognizable versions of the coronavirus can overwhelm the immune system’s early cavalcade if they raid the premises in high-enough numbers—via, for instance, an intense and prolonged exposure event.

With so many factors at play, it’s not hard to see how a few viral particles might still hit their mark. But a body under siege isn’t going to throw its hands up in defeat. “People tend to think of this as yes or no—if I got vaccinated, I should not get any symptoms; I should be completely protected,” Laura Su, an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania, said. “But there’s way more nuance than that.” Even as the virus is raising a ruckus, immune cells and molecules will be attempting to hold their ground, regain their edge, and knock the pathogen back down. Those late-arriving efforts might not halt an infection entirely, but they will still curb the pathogen’s opportunities to move throughout the body, cause symptoms, and spread to someone else. The inhospitality of the vaccinated body to SARS-CoV-2 is what’s given many researchers hope that long COVID, too, will be rarer among the immunized, though that connection is still being explored.

Breakthroughs, especially symptomatic ones, are still uncommon, as a proportion of immunized people. But by sheer number, “the more people get vaccinated, the more you will see these breakthrough infections,” Juliet Morrison, a virologist at UC Riverside, said. (Don’t forget that a small fraction of millions of people is still a lot of people—and in communities where a majority of people are vaccinated, most of the positive tests could be for shot recipients.) Reports of these cases shouldn’t be alarming, especially when we drill down on what’s happening qualitatively. A castle raid is worse if its inhabitants are slaughtered and all its jewels stolen; with vaccines in place, those cases are rare—many of them are getting replaced with lighter thefts, wherein the virus has time only to land a couple of punches before it’s booted out the door. Sure, vaccines would be “better” if they erected impenetrable force fields around every fortress. They don’t, though. Nothing does. And our shots shouldn’t be faulted for failing to live up to an impossible standard—one that obscures what they are able to accomplish. A breached stronghold is not necessarily a defeated stronghold; any castle that arms itself in advance will be in a better position than it was before.

There’s a potential silver lining to breakthroughs as well. By definition, these infections occur in immune systems that already recognize the virus and can learn from it again. Each subsequent encounter with SARS-CoV-2 might effectively remind the body that the pathogen’s threat still looms, coaxing cells into reinvigorating their defenses and sharpening their coronavirus-detecting skills, and prolonging the duration of protection. Some of that familiarity might ebb with certain variants. But in broad strokes, a post-inoculation infection can be “like a booster for the vaccine,” Su, of the University of Pennsylvania, said. It’s not unlike keeping veteran fighters on retainer: After the dust has settled, the battle’s survivors will be on a sharper lookout for the next assault. That’s certainly no reason to seek out infection. But should such a mishap occur, there’s a good chance that “continuously training immune cells can be a really good thing,” Nicole Baumgarth, an immunologist at UC Davis, said. (Vaccination, by the way, might mobilize stronger protection than natural infection, and it’s less dangerous to boot.)

We can’t control how SARS-CoV-2 evolves. But how disease manifests depends on both host and pathogen; vaccination hands a lot of the control over that narrative back to us. Understanding breakthroughs requires some intimacy with immunology, but also familiarity with the realities of a virus that will be with us long-term, one that we will probably all encounter at some point. The choice isn’t about getting vaccinated or getting infected. It’s about bolstering our defenses so that we are ready to fight an infection from the best position possible—with our defensive wits about us, and well-armored bodies in tow.

By Katherine J. Wu (The Atlantic). Illustration by Adam Maida/The Atlantic.

626 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Not sleeping enough, which for a portion of the population is a voluntary choice, significantly modifies your gene transcriptome—that is, the very essence of you, or at least you as defined biologically by your DNA. Neglect sleep, and you are deciding to perform a genetic engineering manipulation on yourself each night, tampering with the nucleic alphabet that spells out your daily health story.

Matthew Walker PhD, Why We Sleep: The New Science of Sleep and Dreams

(via themedicalstate)

872 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some stranger somewhere still remembers you because you were kind to them when no one else was.

57K notes

·

View notes

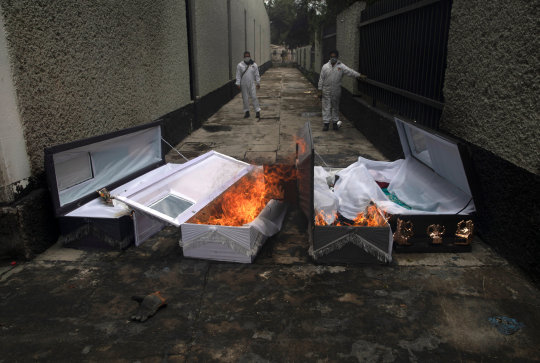

Photo

A Year Like No Other

1. Brooklyn, N.Y., April 20 Bodies were stacked in a refrigerated trailer at the Brooklyn Hospital Center. More than 20,000 New Yorkers died in the spring surge of coronavirus infections. Victor J. Blue for The New York Times

2. Queens, N.Y., April 1 Paramedics worked to resuscitate a coronavirus patient at a hospital. The borough emerged as the center of New York City’s raging outbreak. Philip Montgomery for The New York Times

3. Washington, Oct. 24 Suzanne Brennan Firstenberg set up over 220,000 white flags as part of an art installation outside the D.C. Armory to represent the nation’s death toll from the coronavirus at the time. Stefani Reynolds for The New York Times

4. Houston, July 15 A coronavirus patient on a ventilator at Houston Methodist Hospital. During the summer surge, the hospital created new virus wards, hired traveling nurses, and ramped up testing efforts. Erin Schaff/The New York Times

5. Mexico City, June 24 Workers burned the coffins of Covid-19 victims after their bodies had been cremated. Mexico had one of the highest coronavirus death tolls in the world. Marco Ugarte/Associated Press

6. Wantagh, N.Y., May 24 Olivia Grant hugged her grandmother, Mary Grace Sileo, through a plastic drop cloth hung on a clothesline. It was their first contact since the start of the lockdown caused by the pandemic. Al Bello/Getty Images

7. Manaus, Brazil, May 25 Rows of newly dug graves at a cemetery in Manaus, the Brazilian Amazon’s biggest city, where at one point every Covid-19 ward was full and 100 people a day were dying. Tyler Hicks/The New York Times

8. Manhasset, N.Y., April 19 Eliana Marcela Rendón was comforted by her husband, Edilson Valencia, as her grandmother, Carmen Evelia Toro, 74, lost her battle against Covid-19 at a hospital on Long Island. Victor J. Blue for The New York Times

9. Newark, Del., April 30 A nurse took a moment in a massage chair in an “oasis” room at Christiana Hospital, set up to give stressed medical workers a breather. Erin Schaff/The New York Times

10. Coventry, England, Dec. 8 Medical workers cheered for Margaret Keenan, 90, after she became the first person in Britain to receive the coronavirus vaccine developed by Pfizer and BioNTech. “I feel so privileged,” she said. Pool photo by Jacob King

6K notes

·

View notes

Video

undefined

tumblr

Elephants pass through hotel built upon ancient elephant path, Mfuwe Lodge, Zambia.

65K notes

·

View notes

Quote

The most beautiful people we have known are those who have known defeat, known suffering, known struggle, known loss, and have found their way out of the depths. These persons have an appreciation, a sensitivity, and an understanding of life that fills them with compassion, gentleness, and a deep loving concern. Beautiful people do not just happen.

Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross

(via themedicalstate)

548 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hope everyone is staying strong and safe out there! This storm will pass

69K notes

·

View notes

Text

“In one of the most vivid scenes in the HBO miniseries “Chernobyl” (among many vivid scenes), soldiers dressed in leather smocks ran out into radioactive areas to literally shovel radioactive material out of harm’s way. Horrifically under-protected, they suited up anyway. In another scene, soldiers fashioned genital protection from scrap metal out of desperation while being sent to other hazardous areas.

Please don’t tell me that in the richest country in the world in the 21st century, I’m supposed to work in a fictionalized Soviet-era disaster zone and fashion my own face mask out of cloth because other Americans hoard supplies for personal use and so-called leaders sit around in meetings hearing themselves talk. I ran to a bedside the other day to intubate a crashing, likely COVID, patient. Two respiratory therapists and two nurses were already at the bedside. That’s 5 N95s masks, 5 gowns, 5 face shields and 10 gloves for one patient at one time. I saw probably 15-20 patients that shift, if we are going to start rationing supplies, what percentage should I wear precautions for?

Make no mistake, the CDC is loosening these guidelines because our country is not prepared. Loosening guidelines increases healthcare workers’ risk but the decision is done to allow us to keep working, not to keep us safe. It is done for the public benefit - so I can continue to work no matter the personal cost to me or my family (and my healthcare family). Sending healthcare workers to the front line asking them to cover their face with a bandana is akin to sending a soldier to the front line in a t-shirt and flip flops.

I don’t want talk. I don’t want assurances. I want action. I want boxes of N95s piling up, donated from the people who hoarded them. I want non-clinical administrators in the hospital lining up in the ER asking if they can stock shelves to make sure that when I need to rush into a room, the drawer of PPE equipment I open isn’t empty. I want them showing up in the ER asking “how can I help” instead of offering shallow “plans” conceived by someone who has spent far too long in an ivory tower and not long enough in the trenches. Maybe they should actually step foot in the trenches.

I want billion-dollar companies like 3M halting all production of any product that isn’t PPE to focus on PPE manufacturing. I want a company like Amazon, with its logistics mastery (it can drop a package to your door less than 24 hours after ordering it), halting its 2-day delivery of 12 reams of toilet paper to whoever is willing to pay the most in order to help get the available PPE supply distributed fast and efficiently in a manner that gets the necessary materials to my brothers and sisters in arms who need them.

I want Proctor and Gamble, and the makers of other soaps and detergents, stepping up too. We need detergent to clean scrubs, hospital linens and gowns. We need disinfecting wipes to clean desk and computer surfaces. What about plastics manufacturers? Plastic gowns aren’t some high-tech device, they are long shirts/smocks…made out of plastic. Get on it. Face shields are just clear plastic. Nitrile gloves? Yeah, they are pretty much just gloves…made from something that isn’t apparently Latex. Let’s go. Money talks in this country. Executive millionaires, why don’t you spend a few bucks to buy back some of these masks from the hoarders, and drop them off at the nearest hospital.

I love biotechnology and research but we need to divert viral culture media for COVID testing and research. We need biotechnology manufacturing ready and able to ramp up if and when treatments or vaccines are developed. Our Botox supply isn’t critical, but our antibiotic supply is. We need to be able to make more plastic ET tubes, not more silicon breast implants.

Let’s see all that. Then we can all talk about how we played our part in this fight. Netflix and chill is not enough while my family, friends and colleagues are out there fighting. Our country won two world wars because the entire country mobilized. We out-produced and we out-manufactured while our soldiers out-fought the enemy. We need to do that again because make no mistake, we are at war, healthcare workers are your soldiers, and the war has just begun.”

-Josh Lerner, MD.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

For all you health care workers out there. #COVID19

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes just asking someone if they’re okay can make a world of difference.

3K notes

·

View notes