Text

won't lie i did buy a $3 book just because the title was "Birds Birds Birds Birds Birds Birds" and had a picture of this guy

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Got driftwood?

Where the forest meets the sea - Ruby Beach, Olympic National Park

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this New York Times story:

Winter mornings begin at David Sibley’s Deerfield, Mass., household as they do at my similarly rural place 90-something miles to the west and south, across the New York line: with filling the bird feeders.

“Baby, it’s cold outside” takes on a new meaning when many in your customer base weigh barely as much as a few pieces of pocket change.

The sunflower hearts — shelled sunflower seeds — that we both offer are happily devoured, but they are not the key ingredient in the birds’ survival. What the American goldfinches, white-breasted nuthatches, house finches and the rest cannot live without in these coldest months is a suite of physical and behavioral survival strategies hard-earned over millions of years of evolution.

These tactics, and the birds themselves, are the subject of “The Courage of Birds: And the Often Surprising Ways They Survive Winter,” the recent book by Pete Dunne, a prolific author about all things bird and former director of the Cape May Bird Observatory in New Jersey. It was illustrated by Mr. Sibley, a naturalist, author and illustrator perhaps best known for “The Sibley Guide to Birds.”

“Welcome to winter, nature’s proving ground,” Mr. Dunne writes, “where there is no prize for second place during these four months. Across the Northern Hemisphere, it’s ‘survivor take all.’”

Peak birding time this is not.

The birds are “meeting the season beak-on,” Mr. Dunne writes, and take note: A bird’s bill is not insulated. Nor are its legs and feet. So all those vulnerability points tend to be smaller in species that winter in cold zones — scaled down as a result of the natural selection process across countless generations.

Feathers are the first line of defense against weather, Mr. Sibley said in a recent conversation, and besides enabling flight, “they’re streamlining, waterproofing, windproofing, coloration — all those things.” And down feathers, the soft, fluffy kind closest to the bird’s body, he added, are “the most effective insulation known.”

Using tiny muscles where their feathers attach to skin, birds can raise and lower them, thickening the insulating layer around their bodies, he said, “like putting on an extra jacket or getting into a sleeping bag.”

Also thanks to feathers, a bird can tuck in its most vulnerable body parts, particularly overnight. Heads are turned so beaks can be buried into the shoulder-like scapular feathers atop a wing “to reduce heat loss and recycle warmth in the same way people do when breathing into cupped hands,” Mr. Dunne writes. By perching on one leg, the bird can pull the other up into safety, conserving more heat.

Watch for other protective behaviors: as birds turn their backs to the sun to soak in maximum warmth, for instance, or as they cuddle, clustering together to share warmth.

Overnight, many birds roost in tree cavities, nest boxes or dense vegetation, sometimes together. Certain species, including the black-capped chickadee — a familiar bird in roughly the northern half of the country and in portions of Canada and Alaska — may get through a cold night by lowering their metabolism, respiration and heart rates, as well as their body temperature, even down to 50 degrees, to induce a hibernation-like state of torpor.

Another cold-defying strategy of birds is shivering on demand to raise their body heat — that’s what chickadees do to emerge from torpor.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

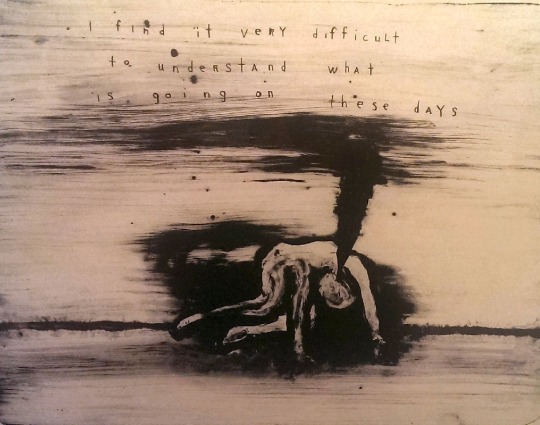

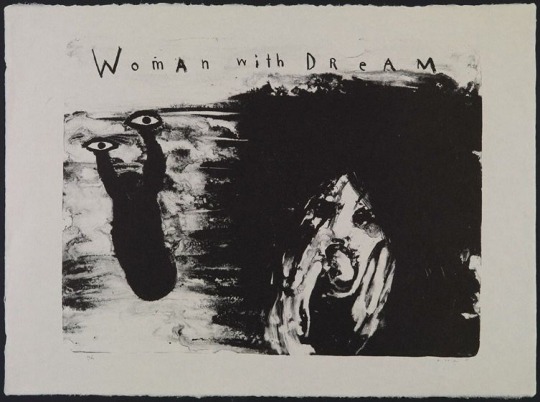

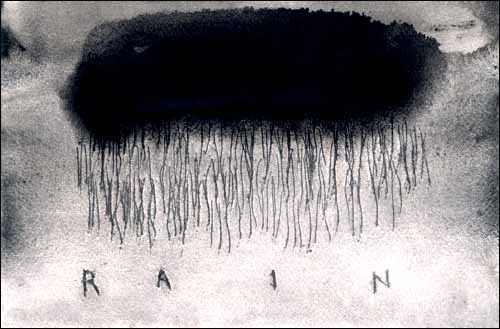

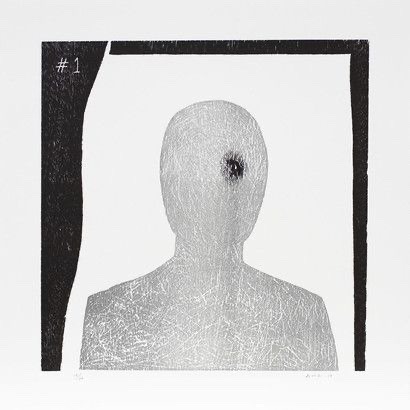

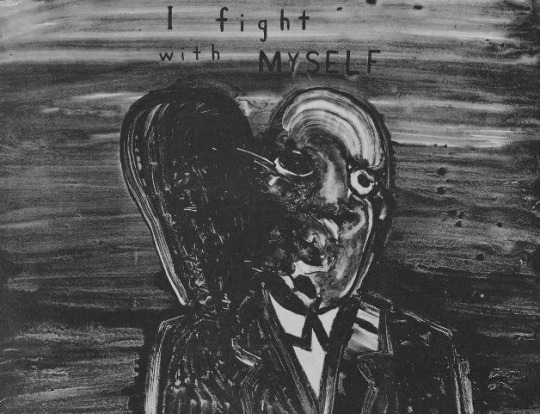

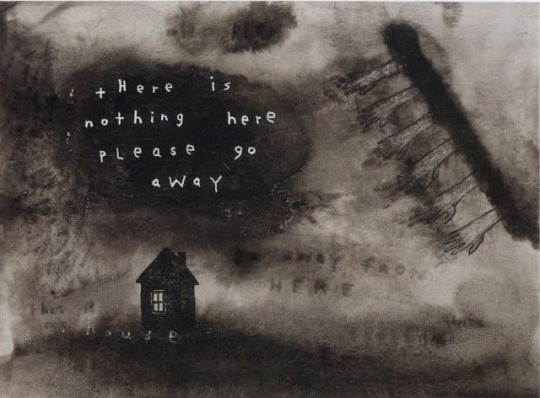

David Lynch, selected paintings and lithographs.

“When I’m not painting, I’m thinking about painting.”-David

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

Great Spotted Woodpecker/större hackspett. Värmland, Sweden (February 1, 2015).

342 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Miracle of St Justus, c.1630 by Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577–1640)

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean Siméon Chardin: Natureza morta con xerra e pexegos (ca. 1728)

10 notes

·

View notes