Text

#ok. wtf actually. it's probably a parent and baby? but also. e_e#???#questions n things to distract myself with#in a marina... so used to human contact?#is that uni/patch for animal control or.. which branch of ???#is this usa or... e_e#Galina is boat name... could be northern Europe but afaik this sea otter is the kind limited to northern pacific but not sure with 360p lol

44K notes

·

View notes

Text

Something to fact check, then go down the rabbit hole. LOBSTERS. Could conditions allow you to battle cephalopods for dominance? Well. More like... Post-vertabrate potentials. Land lobsters used like horses for Land Squid in 600million years.

i think that the "i do not control the ____" memes are generally tame and do not lend enough credence to the genuine absurdity of the original line that is

175K notes

·

View notes

Text

Prison-Based Animal Programs: Cats, Inmates, and Masculinity

by Sophiane Nacer, Metropolitan State University of Denver

I. Introduction

Prison-based pet programs (PAPs) are a relatively new phenomenon, though interactions between prisoners and animals are anything but (Furst, 2006). PAPs present an opportunity for inmates to engage in meaningful work and give back to the community while also experiencing the therapeutic effects that animal companionship provides (Fournier, 2016). However, there may be more to PAPs than meets the eye. In a prison environment where the inmate code legitimizes the destructive ideals of toxic masculinity, opportunities to practice compassion, empathy, vulnerability, and emotional breadth can be vital to preventing inmates from recidivating upon release (Fournier, 2016). PAPs that use cats may be particularly helpful in inmate resocialization, rehabilitation, and reintegration due to the traditional association between felines and femininity that provides the unique potential to dismantle destructive masculine ideas, ideals, and behaviors in inmates (Fournier, 2016).

II. Hegemonic Masculinity and Toxic Masculinity

Hegemonic masculinity is defined as the dominant notion of masculinity in a given context, both historical and geographical, that is comprised of both prosocial and antisocial notions of masculine expectations (Kupers, 2005). Fatherhood, pride in accomplishments, self-reliance, courage, and action-orientation are all examples of masculine attributes that are culturally accepted and valued (Fournier, 2016). Misogyny, ruthless competition, devaluation of feminine attributes, a need to dominate and control others, a readiness towards anger and violence, and hierarchical intermale dominance, are all examples of socially destructive masculine attributes that are perpetuated by the contemporary hegemonic masculine standard (Kupers, 2005). The term toxic masculinity is used to delineate these destructive attributes from the prosocial ones, creating a constellation of socially regressive male traits (Kupers, 2005).

Toxic masculinity is literally coded into prison life as the “inmate code”, which dictates that a “real man” or a “stand-up con” does not display weakness, does not display emotion other than anger, does not depend on anyone nor display any vulnerabilities, and is quick to violence to defend his place in the prison hierarchy (Kupers, 2005). Men who may not have displayed any overtly toxic masculine behaviors on the outside are forced to adapt to the culture of hypermasculine posturing and violence as a way to survive, through a process known as prisonization (Fournier, 2016). Toxic masculinity within prisons is also reinforced by the institution itself. Both inmates and staff, particularly correctional officers, are expected to be tough, show no vulnerabilities, constantly engage in an intermale struggle for power, and solve problems through brute force (Kupers, 2005). A key example of this is the practice of cell extraction, in which inmates and officers, dressed in riot gear and heavily armed, engage in an acute fight for dominance (Kupers, 2005). Inevitably, cell extractions serve to confirm an inmate’s loss of power and control, two things toxic masculinity requires of a “real man”. With no other acceptable or attainable means of confirming his masculinity, the inmate seeks to overpower and control weaker inmates through acts of violence, such as rape and other forms of physical assault (Fournier, 2016).

The internalization of and socialization to prison’s culture of toxic masculinity is deeply harmful, both to the inmate himself and to society. Six out of seven inmates will be released back into society after serving their prison sentence, making the need for effective rehabilitation and tools for reintegration critical to decreasing recidivism and social harm (Nellis, 2021). However, the shift from rehabilitation to incapacitation and confinement seen in the 1970s coupled with male resistance to therapy has deeply impaired the ability to counter these devastating effects of prison (Kupers, 2005).

III. Men, Mental Health, and Prison

The 1970s not only marked the transition from rehabilitation to incapacitation, but it also marked the beginning of a massive increase in incarceration (Kupers, 2005). As the prison population has quadrupled in the last three decades so has the proportion of inmates needing treatment for significant emotional and psychological problems, a trend attributed to deinstitutionalization, tough-on-crime initiatives, and a shrinking public mental health budget (Kupers, 2005). Prison mental health resources have failed to increase alongside their ever-growing population, meaning that said resources are typically reserved for only the most serious cases, such as prisoners suffering from acute psychosis, suicidal ideation or attempts, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder (Kupers, 2005). This leaves many individuals, including those court-ordered to attend therapy for anger management, sex offenses, and substance abuse, without any recourse (Kupers, 2005).

Further compounding the limitations of prison mental health treatment is the lack of confidentiality and privacy. Oftentimes, particularly in maximum security units where prisoners are confined to their cells for 23 hours per day, there is inadequate staff to facilitate transport to and from private treatment areas (Kupers, 2005). As such, “cell front” therapy has become increasingly popular (Kupers, 2005). Cell front therapy occurs with the inmate talking to their mental health provider through their cell door, in full view of neighboring inmates and passing correctional officers (Kupers, 2005). This prevents any measure of confidentiality and may put the prisoner at risk depending on the topic being discussed. Institutional rules surrounding mandatory reporting further compromise the privacy of the inmate and any confidentiality cell-front therapy could provide (Kupers, 2005). Lack of resources paired with poor confidentiality serves as external barriers to prisoners obtaining necessary treatments, though these are not the only barriers.

Men, both outside and inside of prison, tend to underreport emotional and psychological distress, only seeking help when things have reached a point of crisis (Kupers, 2005). This reluctance to seek mental health treatment has been attributed to toxic masculinity, in that it encourages men to repress all emotions other than anger and avoid actions that could be interpreted as dependency or weakness (Woodson, 2019). To succeed in therapy, men must reject a certain amount of the hegemonic masculinity that they have been socialized to since childhood, and in doing so place themselves in a position of rare vulnerability (Kupers, 2005). This is especially difficult for incarcerated men, who are subjected to toxic masculinity at a far greater intensity yet who are also most in need of treatment. Studies have shown that over half of all inmates in US jails and prisons suffer from mental illness, a rate 2-4 times higher than the general population (Satlin, 2013). Suicide rates are also high amongst the incarcerated population at 46 in every 100,000 in US jails (Carson, 2020a) and 21 per every 100,000 in US prisons (Carson, 2020b), compared to 13.4 per every 100,000 in the general population as of 2016 (Suicide, 2021). Men represent 85.7% of jail suicides (Carson, 2020a), 96.2% of prison suicides (Carson, 2020b), and are 3.7 times more likely to commit suicide than women amongst the non-incarcerated US population (Suicide, 2021).

Mental health services in US correctional facilities today are ineffective, unsafe, and in dire need of both reformation and increased funding. Society’s idealization of traditional masculinity, the most destructive traits of which are perpetuated by pervasive toxic masculinity, has created a significant barrier to men seeking the help they need (Kupers, 2005). The exaggerated form of toxic masculinity that exists within prisons, reinforced both by the inmate code and the institution itself, is directly antithetical to the purpose of corrections as prisoners adopt antisocial traits as a survival technique rather than prepare prosocial coping mechanisms for their eventual reentry into society (Woodson, 2019). For as long as the incapacitation model remains favored, it is unlikely that we will see drastic restoration to rehabilitative efforts. However, prison-based animal programs offer some hope of not only facilitating therapeutic efforts but also minimizing the assimilation of toxic masculine traits and preparing inmates for successful reintegration.

IV. Prison-Based Animal Programs

Inmates and animals have a centuries-old history of interaction. Whether its pigeons, lizards, mice, or cats, inmates have shown an appreciation for animals that has surpassed that of the non-incarcerated (Furst, 2006). Researchers studying inmate poetry commented that “perhaps the scarcity of opportunities to develop relationships with non-inmates and the difficulties inherent in connecting with fellow prisoners are responsible for the striking number of poems about the importance of animals" (Furst, 2006). One of the most famous displays of animal admiration from an inmate is that of Robert Stroud, the “Birdman of Alcatraz”, whose rearing of canaries in Leavenworth Federal Prison led him to be recognized as a published ornithologist while incarcerated (Strimple, 2003). There are also less famous cases, such as the first successful prison-based animal program that was established accidentally in 1975, when inmates at Lima State Hospital for the Criminally Insane found and cared for an injured sparrow (Strimple, 2003). After noticing an improvement in inmates’ cooperation with each other and staff, the hospital initiated a year-long comparison study between two identical wards, with one allowing pets and the other not (Strimple, 2003). They found that inmates residing in the pet ward required half the amount of medication, had fewer violent incidences, and had no suicide attempts where the non-pet ward had eight (Strimple, 2003). Considering the body of research that exists supporting the use of animal-assisted therapy in individuals with both physical and psychological illnesses, such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, anxiety, PTSD, and depression, these results showed that animals could have the same beneficial effects for a criminal population (Furst, 2006). This prompted other institutions to create their own prison-based animal programs (PAPs), and by 2006 a nationwide survey of PAPs found that there were 159 PAP sites in forty-six participating states (Furst, 2006). Although this number has continued to grow, a more recent survey has not yet been conducted.

PAPs are generally categorized into eight different models- visitation programs, wildlife rehabilitation programs, livestock care programs, pet adoption programs, service animal socialization programs, vocational programs, community service programs, and multimodal programs (Furst, 2006). The most common PAP design found in the study was the community service model (33.8%), in which participating inmates train and care for companion animals that are then adopted out to the community, followed by the service animal socialization model (21.1%), which typically train dogs to assist individuals with disabilities (Furst, 2006). 66.2% of PAPs used dogs, followed by cattle (12.7%) and horses (12.7%), where only 1.4% used cats (Furst, 2006). The majority of PAPs required interviews prior to participation (71.8%) as well as a history of good behavior or standing within the institution (54.7%) (Furst, 2006). 59.2% excluded inmates charged with certain crimes, most commonly crimes against animals (59.5%) and sex offenses (45.2%) (Furst, 2006). Funding for PAPs was reported to come primarily from fundraising (52.1%) amongst inmates, staff, the public, and privately-owned companies like PetCo, Petsmart, and Walmart, with further donations received through the humane society, shelter, or rescue with whom the prison partnered (Furst, 2006).

When asked if they would recommend PAPs to other prison administrators, 60 out of the 61 respondents (98.4%) confirmed that they would, with the one exception commenting that although beneficial to the inmates the programs are not revenue-generating (Furst, 2006). In support of their recommendation, respondents noted that PAPs had many benefits for inmates, including instilling a sense of responsibility and heroism, teaching job skills and parenting skills, providing meaningful work, encouraging patience, boosting self-esteem, reducing violent incidents, and decreasing anxiety amongst both inmates and staff (Furst, 2006). These attributes seem to run in direct contradiction with prison’s culture of toxic masculinity, by substituting it with a culture of compassion, community-mindedness, cooperation, and patience. A study that surveyed both program participants and members of the general prison population who interacted with PAP animals found that inmates “were more nurturing than aggressive, more expressive than stoic, and more cooperative than competitive” (Fournier, 2016). Participants also demonstrated an increased range of emotions which they openly expressed in the presence of others- discussing the joy of successes, the patience required for training, and the grief that comes when their dogs got adopted- something quite different than the heavily constricted expressions of emotion dictated by the inmate code and even normative hegemonic masculinity (Fournier, 2016). PAPs provide inmates with the opportunity to practice healthy masculinity through dedicating their time and efforts to the care of PAP animals. In return for their efforts, inmates are given unconditional positive regard and companionship, enabled to receive and give physical affection, and provided a confidant in an isolating, lonely, and treacherous environment (Fournier, 2016).

When asked, administrators at facilities with PAPs said that there were no downsides to the program (60%), with only 10.1% citing staff resistance as the only negative, rather than a flaw in the program itself (Furst, 2006). Anecdotally, administrators believed that recidivism amongst PAP participants was drastically lower than the general prison population, but no empirical studies have yet been performed to confirm this (Furst, 2006). With more than 2 million people incarcerated in the US and more than 6.5 million pets who become homeless every year the overwhelming support for PAPs presents a promising, life-saving option (Pets by the Numbers, 2020). PAPs, particularly the community service model in which prisons partner with animal shelters and rescues, are an opportunity to help both animals and prisoners by encouraging the unique bond that has long existed between the two and giving a second chance to two populations in dire need of one.

V. The Evolution and Perception of Cats

Cats were improbable candidates for domestication. Wild cats are territorial and live a solitary existence outside of mating and rearing young, making them the only domesticated asocial animal, though the extent to which cats are truly domesticated remains up for debate (Driscoll, MacDonald, & O’Brien, 2009). Dog domestication began 27,000 to 40,000 years ago after humans, living as nomadic hunter-gatherers, found utility in less fearful wolves as barking sentinels and began a long process of artificial selection (Driscoll, MacDonald, & O’Brien, 2009). Cats, on the other hand, do not appear to have been artificially selected by humans at all. Instead, approximately 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, they pioneered their own domestication through natural selection after having seen the benefit of hunting near human granaries and settlements (Driscoll, MacDonald, & O’Brien, 2009). In this sense, cats co-evolved alongside humans, where dogs evolved under direct human influence.

In addition to their asocial origins and relatively short period of self-domestication, cat behavior is shaped by their status as both predator and prey (Dowling, 2020). Renowned for their hunting skills, cats have traditionally been used to deter mice and other pests; however, their small size places them at risk of being hunted by predators such as large canids, birds of prey, larger felines, and other carnivores (Driscoll, MacDonald, & O’Brien, 2009). As such, cats tend to be cautious, especially in new situations, and have developed a sophisticated body language that masks signs of physical and psychological distress in an effort to avoid predation (Dowling, 2020). This leaves many non-cat-savvy people with the impression that cats are unfriendly, unapproachable, and unpredictable, when in fact cats are simply outliers (Dowling, 2020).

Oftentimes the principal mistake people make when trying to understand cats is to compare them to another very popular pet- dogs. Dogs, who have undergone many years of domestication during which friendliness and obedience were intentionally selected for, are prosocial predator animals who tend to be confident, approachable, and expressive (Dowling, 2020). Over the course of their evolution, dogs even evolved a special orbital muscle that allows them to mimic the facial expressions of human infants; cats, lacking this muscle, are often denigrated as having “blank stares” or “evil eyes” (Dowling, 2020). Research has shown, however, that there is no difference in the strength of bonds that cats and dogs form with their owners, nor is there a difference in the health benefits owning either provides in terms of lower rates of anxiety and depression, better cardiovascular health, and self-esteem (Dowling, 2020).

VI. Felines and Femininity

The oldest example of cats and femininity being linked together is found in Bastet, the cat goddess of fertility, domesticity, childbirth, and sexuality (Mark, 2016). Bastet and the cats of ancient Egypt, a relatively egalitarian society, were revered by both men and women (Mark, 2016). As time progressed, however, the association between cats and femininity persisted while the reverence was lost.

In 1891 F. B. Harrison, a statesman who would later become the Governor-General of the Phillipines, wrote in The Journal of Education:

"The fiery spirit, the loud bark, the watchful temperament of the dog give him always a male aspect; and the sleek sleepiness, the treble mew, the spiteful deceit of the cat combine to render her female in character." (Gleeson, 2016)

By the 19th century, a distinct trend could be noticed in English writing where cats were associated with women and the feminine, while dogs were associated with men and the masculine (Gleeson, 2016). Unlike ancient Egypt, cats and women were not elevated through this comparison. Instead, traits such as aloofness, disloyalty, unpredictability, greed, selfishness, hypersexuality, pettiness, and spitefulness were attributed to cats and the women who were said to resemble them (Smith, 2009). Single women with one or more cats were- and still are- derogatorily labeled “crazy cat ladies”, physical altercations between women are called “cat fights”, and sexually aggressive women are “cats in heat” (Smith, 2009). Furthermore, associating a man with cats- and, by extension, women- is used to challenge his masculinity. Calling a man a “pussy” is considered a grave insult for its association with both female genitalia and cats, and is a sure way to start a fight (Smith, 2009). Even just owning a cat can cause a man to be seen as less masculine, gay or, according to a recent study, less datable (Kogan & Volsche, 2020).

This delineation separating men from cats is an example of toxic masculinity’s drive to separate all things male from all things female, lest a man’s masculinity be degraded by feminine associations (Smith, 2009). Dogs are “man’s best friend”- action-oriented, quick to please, and obedient- one does not usually have to work hard to gain a dog’s affection, or at least not as hard as one might have to work for a cat’s (Gleeson, 2016). This dynamic caters to toxic masculinity, which has taught men that they should not have to work hard for anyone’s affection; instead, women- and animals- should flock to them and vie for their attention (Gleeson, 2016). According to these same standards, both cats and women are small, weak, and difficult to handle (Smith, 2009). This makes them legitimate targets for abuse, which can be used to affirm masculinity when men feel powerless or when he needs to prove his masculinity to his peers (Smith, 2009).

However, a new movement- prompted by urbanization, apartment living, and social media- is encouraging men to discard this toxic interpretation of masculinity and “embrace a gentler, more thoughtful kind of masculinity” through cat ownership (Gleeson, 2016). Male cat owners in Australia were found to be 24% more likely to vote for liberal candidates, 29% less likely to believe homosexuality is immoral, and more likely overall to read and play boardgames (Gleeson, 2016). This indicates that, in addition to embracing a traditionally feminine pet, they have globalized their disregard for masculine ideas, such as conservativism and homophobia. While we cannot say which one caused the other- if owning a cat prompted them to adopt a non-traditional masculine identity or if adopting a non-traditional masculine identity prompted them to own a cat- the correlation suggests that associating with cats may do more to combat toxic masculinity than with other animals (Gleeson, 2016).

VII. Prison-Based Cat Programs

While still extremely rare, the number of cat PAPs has increased from the solitary program noted in the 2006 PAP survey (Can you have a cat in prison?, 2020). Perhaps the most famous is Indiana State Prison’s cat adoption program where inmates in the maximum-security prison, including those on death row, can apply to adopt a cat from the local animal shelter- a privilege so popular amongst inmates that there is an extensive waitlist (Can you have a cat in prison?, 2020). The program is funded by the inmates themselves, who are expected to keep a job and pay for all associates expenses, with many choosing to make their own cat furniture and toys as well (Can you have a cat in prison?, 2020). With the exception of death row inmates, who are prohibited from interacting with others, cats are permitted to wander the cell block under their owner’s watchful eye to interact with inmates who do not have cats of their own (Can you have a cat in prison?, 2020). This program is one of the few PAPs that are therapeutically focused, in that the element of community service comes secondary to the long-term benefits inmates receive from permanently adopting a cat (Furst, 2006). Maleah Stringer, the executive director of the Animal Protection League, the shelter partner that provides cats to the prison, says:

“There’s no more risk of the animals being hurt in prison than there is when we adopt to the normal public. The guys stay out of trouble because they know if they get in trouble, they’re going to lose the program. We’ve had more issues with mistreated animals coming back from adoptions than we ever do from the prison program.” (Can you have a cat in prison?, 2020)

Seeing the success of this program- including a significant decrease in violent incidences and improved mental health among inmates and staff- another cat PAP was established at the Pendleton Correctional Facility, another maximum-security prison in Indiana (Can you have a cat in prison?, 2020). This program operates using a community service model where inmates prepare cats for public adoption (Furst, 2006). The cats remain in a community room rather than in individual cells, and inmates report to the room every morning for their work hours (Can you have a cat in prison?, 2020). Inmates in this PAP along with other cat PAPs focus on socializing cats, building their confidence, addressing any acute behavioral issues, and teaching them basic tricks (O’Conner, 2020). Socialization is particularly important for feral cats, semi-feral cats, and cats who have undergone traumatic events or circumstances, all of whom make up a large percentage of homeless cats (O’Conner, 2020).

The process of socializing a cat is very rewarding but requires an excess of patience and the understanding that cats will acclimate on their own time rather than yours (O’Conner, 2020). This is one of the attributes that perhaps most differentiates cats from dogs, and may prove even more effective when it comes to socializing inmates towards prosocial behaviors and away from toxic masculinity. Patience, empathy, and compassion are exercised in any PAP, but seem to be especially pronounced in inmate interactions with cats (O’Conner, 2020). Dog PAPs are centered around obedience training and task-completion, which actually reinforces some aspects of toxic masculinity- such as a need for control and dominance over others (Fournier, 2016). Recognizing and adapting to the needs of others is a critical skill for prosocial interactions and reintegration, both of which are necessary when working with cats (Kupers, 2005).

Cats being a symbol of femininity and their traditional role as “women’s pets” also presents a unique opportunity to overcome toxic masculinity (Gleeson, 2016). Cat PAPs allow inmates to safely embrace a kinder, more compassionate culture of masculinity through their acceptance rather than degradation of a feminine symbol. The value inmates assign to animals, for their nonjudgmental and affectionate companionship, makes cats an ideal form through which to introduce non-hegemonic masculinity into a hypermasculine environment where displays of femininity are traditionally met with violence (Fournier, 2016). In theory, through this introduction, global improvement would occur to the point where the inmate is not influenced by the ideals of toxic masculinity in either choosing his pet, nor in his actions, choices, and opinions (Fournier, 2016). This theory is supported by the aforementioned survey of Australian “cat men”, who showed a global denunciation of toxic masculinity in their rejection of homophobia, conservativism, and stereotypical male hobbies (Gleeson, 2016). This globalized version of healthy masculinity may also remove some of the barriers that prevent successful mental health care within prisons; although cats can do little to increase the funding available to prison mental health services, their promotion of healthy masculinity may leave inmates more open to therapeutic intervention and, if nothing else, can serve as the most confidential of confidants (Kupers, 2005).

Finally, cats are well-suited to the structural limitations that prisons impose. Cat- more than dogs- can live in cells where space is limited and outdoor exercise may not be guaranteed (Can you have a cat in prison?, 2020). They also do not require frequent outdoor access, which decreases the need for staff involvement and makes them ideal for high-to-maximum security units where PAPs are otherwise difficult to accommodate (Kupers, 2005). While there has not been a survey comparing PAP expenses, it seems likely that cat PAPs incur fewer expenses given the amount the average cat owner spends yearly versus that which a dog, horse, or cattle owner spends (Pet Care Costs, 2017). In a time where prisons are looking for cost-effective methods to reduce recidivism, violent incidents, and mental illness amongst their populations, and animal shelters are looking for ways to save the 860,000 homeless cats euthanized each year, cat PAPs present a unique solution to both (Pets by the Numbers, 2020).

Conclusion

The culture of toxic masculinity degrades both women and cats while legitimizing their abuse as a way of affirming one’s masculinity (Smith, 2009). That same culture amplifies the physical and psychological dangers of confinement by creating intermale competition, encouraging violence and anger, and legitimizing the abuse of weaker inmates in the interest of confirming one’s power within prison walls (Kupers, 2005). In this way toxic masculinity serves to both manufacture and perpetuate violence, crime, and societal harm. Finding novel, inexpensive, and prosocial ways to combat the destructive aspects of hegemonic masculinity both within and outside of correctional facilities is critical, particularly in a time where rehabilitation is set aside in favor of incapacitation and funding is being diverted away from mental health resources to pay for an ever-growing prison population (Kupers, 2005). PAPs are on the forefront of innovative therapeutic methods that benefit both the participating inmates and the community at large (Fournier, 2016). Cat programs, although currently rare, should be considered especially effective for their potential to globally dismantle socialized toxic masculinity and prisonization.

Works Cited

Can you have a cat in prison? (2020, November 18). Retrieved May 01, 2021, from https://prisoninsight.com/can-you-have-a-cat-in-prison/

Carson, E. A., & Cowhig, M. P. (2020a). Mortality in Local Jails, 2000-2016 – Statistical Tables (pp. 1-29, Rep. No. NCJ 251921). Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. doi:https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mlj0016st.pdf?utm_content=mci&utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery

Carson, E. A., & Cowhig, M. P. (2020b). Mortality in State and Federal Prisons, 2001-2016 – Statistical Tables (pp. 1-24, Rep. No. NCJ 251920). Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. doi:https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/msfp0116st.pdf

Dowling, S. (2020, May 20). Why do we think cats are unfriendly? Retrieved May 03, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20191024-why-do-we-think-cats-are-unfriendly

Driscoll, C. A., Macdonald, D. W., & O'Brien, S. J. (2009). From wild animals to domestic pets, an evolutionary view of domestication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(Supplement 1), 9971-9978. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901586106

Fournier, A. K. (2016). Pen pals: An examination of human–animal interaction as an outlet for healthy masculinity in prison. Men and Their Dogs, 175-194. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-30097-9_9

Furst, G. (2006). Prison-based animal programs. The Prison Journal, 86(4), 407-430. doi:10.1177/0032885506293242

Gleeson, H. (2016, December 11). Hail the rise of cat men, an antidote to toxic masculinity. Retrieved May 01, 2021, from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-12-11/the-rise-of-cat-men-antidote-to-toxic-masculinity/8082618?nw=0

Kogan, L., & Volsche, S. (2020). Not the cat’s Meow? The impact of posing with cats on Female perceptions of Male Dateability. Animals, 10(6), 1007. doi:10.3390/ani10061007

Kupers, T. A. (2005). Toxic masculinity as a barrier to mental health treatment in prison. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(6), 713-724. doi:10.1002/jclp.20105

Mark, J. J. (2016, July 24). Bastet. Retrieved May 8, 2021, from https://www.worldhistory.org/Bastet/#:~:text=Bastet%20is%20the%20Egyptian%20goddess,associated%20with%20women%20and%20children.

Nellis, A. (2021). No End in Sight: America's Enduring Reliance on Life Imprisonment (pp. 1-45, Rep.). Washington, D.C.: The Sentencing Project. doi:https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/no-end-in-sight-americas-enduring-reliance-on-life-imprisonment/

O'Connor, G. (Director). (2020, November 19). The Cats that Rule the World: Prison Cat, Galileo [Video file]. Retrieved May 1, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nqGvJlDO5Vo&t=14s

Pet Care Costs. (2017, May 17). Retrieved May 8, 2021, from https://www.aspca.org/sites/default/files/pet_care_costs.pdf

Pets by the numbers. (2020, December 26). Retrieved May 07, 2021, from https://humanepro.org/page/pets-by-the-numbers

Satlin, A. (2013, February 04). Mental illness soars in prisons, jails while inmates suffer. Retrieved May 9, 2021, from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/mental-illness-prisons-jails-inmates_n_2610062

Smith, S. E. (2009, September 26). Felinity and Femininity [Web log post]. Retrieved May 01, 2021, from http://meloukhia.net/2009/09/felinity_and_femininity/#:~:text=Today%2C%20of%20course%2C%20cats%20are,who%20like%20cats%20are%20emasculated.&text=Cats%20and%20female%20sexuality%20are,they%20are%20objectified%20and%20sexualized.

Strimple, E. O. (2003). A history of prison inmate-animal interaction programs. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(1), 70-78. doi:10.1177/0002764203255212

Suicide. (2021, May 2). Retrieved May 9, 2021, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide

Woodson, M. (2019). The Best We Can Be: How Toxic Masculinity Creates a Second Inescapable Situation for Inmates. Public Interest Law Reporter, 24(2).

980 notes

·

View notes

Text

No original post. Time to debunk this shit like bad Facebook diet memes.

POV: mister Devon Price, PhD, telling me that I am right about everything

Source: Unmasking Autism, discovering the new faces of neurodiversity

146K notes

·

View notes

Text

I finished reading The Lord of the Rings for the first time in my life. With all of *vague gesture at everything* this going on.

I Am Not Okay

24K notes

·

View notes

Text

I have some thoughts about Latra Sedai

Ok, full disclaimer: I've never read the books, but I have read much of the WoT wiki, so I exist in a liminal space where I am both spoiled and unspoiled. That said, the below is approaching this from a show-only viewpoint. I welcome insights from book knowledge, but please don't @ me with "actually, in the books X happened", because I'm not interrogating this from a book perspective.

The show's choice to have the same person be the one to entrust the sa'angreal (ok, I forgot it's name, there are too many godsdamn names) to the Aiel and to be the one who founds Rhuidean as the place of trials was just fucking brutal. Because it's been hundreds upon hundreds of years at this point: we see Latra argue with Lews in the S1 cold open, where (IIRC) she was the head of the female Aes Sedai?? Indicating she was old enough to be established in her power at that point. So presumably she was alive during the drilling of the Bore. And then she lived through the War, and through the Breaking, and hundreds of years after. She lived through the godsdamn apocalypse, she witnessed the destruction of Utopia -- and through all of that, one of her greatest griefs must have been what the Aiel became. To be there, at the beginning, when she entrusted the future "to peace", and then to be there at the end, when the culture of the "true Aiel", the ones who had kept to their oaths, had withered and died, and the only ones left were their descendants who had chosen violence -- that must have been the cruelest twist of the knife, after everything she had seen.

And yet

AND YET

She must have known she was sending them out to die. She must have known that! It was the middle of the literal apocalypse! Everyone was dying! The world was ending! And she was entrusting these precious objects to people who swore they would never even defend themselves! How did she think this was going to go? She sends ten thousand trees out into the world with the hope that maybe one will survive. Which means she had the expectation that 99.99% of the people she is entrusting this task to are going to die. And then she has the temerity to be furious that some of them decided that that was a raw deal, and that they were going to change the terms of the bargain? What did she think was going to happen.

I understand her grief. She had lost an actual utopia, and by that point, she was the only one who even remembered it ever existed. I even understand her anger -- the Aiel who remained were oathbreakers, and they had spent hundreds of years telling themselves that they were the only ones with honor. How unbelievably painful it must have been, to see how far they had fallen. And yet. She is very, very far from blameless in this matter. She was the one who set upon them this impossible burden. She was the one who sent 9,999 wagons out into the breaking of the world to die for the chance that one would live. She was the one who accepted their oath, knowing what it would mean for their odds of survival. Surely some of her anger must have been directed inward, in recognition that she set them up to fail. Surely some of her grief must have been at her own actions. Surely some of it must have been.

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

How do they keep making later and later stages of late-capitalism

59K notes

·

View notes

Text

Saw a fun little conversation on Threads but I don't have a Threads account, so I couldn't reply directly, but I sure can talk about it here!

I've been wanting to get into this for awhile, so here we go! First and foremost, I wanna say that "Emmaskies" here is really hitting the nail on the head despite having "no insider info". I don't want this post to be read as me shitting on trad pub editors or authors because that is fundamentally not what's happening.

Second, I want to say that this reply from Aaron Aceves is also spot on:

There are a lot of reviewers who think "I didn't enjoy this" means "no one edited this because if someone edited it, they would have made it something I like". As I talk about nonstop on this account, that is not a legitimate critique. However, as Aaron also mentions, rushed books are a thing that also happens.

As an author with 2 trad pub novels and 2 trad pub anthologies (all with HarperCollins, the 2nd largest trad publisher in the country), let me tell you that if you think books seem less edited lately, you are not making that up! It's true! Obviously, there are still a sizeable number of books that are being edited well, but something I was talking about before is that you can't really know that from picking it up. Unlike where you can generally tell an indie book will be poorly edited if the cover art is unprofessional or there are typoes all over the cover copy, trad is broken up into different departments, so even if editorial was too overworked to get a decent edit letter churned out, that doesn't mean marketing will be weak.

One person said that some publishers put more money into marketing than editorial and that's why this is happening, but I fundamentally disagree because many of these books that are getting rushed out are not getting a whole lot by way of marketing either! And I will say that I think most authors are afraid to admit if their book was rushed out or poorly edited because they don't want to sabotage their books, but guess what? I'm fucking shameless. Café Con Lychee was a rush job! That book was poorly edited! And it shows! Where Meet Cute Diary got 3 drafts from me and my beta readers, another 2 drafts with me and my agent, and then another 2 drafts with me and my editor, Café Con Lychee got a *single* concrete edit round with my editor after I turned in what was essentially a first draft. I had *three weeks* to rewrite the book before we went to copy edits. And the thing is, this wasn't my fault. I knew the book needed more work, but I wasn't allowed more time with it. My editor was so overworked, she was emailing me my edit letter at 1am. The publisher didn't care if the book was good, and then they were upset that its sales weren't as high at MCD's, but bffr. A book that doesn't live up to its potential is not going to sell at the same rate as one that does!

And this may sound like a fluke, but it's not. I'm not naming names because this is a deeply personal thing to share, but I have heard from *many* authors who were not happy with their second books. Not because they didn't love the story but because they felt so rushed either with their initial drafts or their edits that they didn't feel like it lived up to their potential. I also know of authors who demanded extra time because they knew their books weren't there yet only to face big backlash from their publisher or agent.

I literally cannot stress to you enough that publisher's *do not give a fuck* about how good their products are. If they can trick you into buying a poorly edited book with an AI cover that they undercut the author for, that is *better* than wasting time and money paying authors and editors to put together a quality product. And that's before we get into the blatant abuse that happens at these publishers and why there have been mass exoduses from Big 5 publishers lately.

There's also a problem where publishers do not value their experienced staff. They're laying off so many skilled, dedicated, long-term committed editors like their work never meant anything. And as someone who did freelance sensitivity reading for the Big 5, I can tell you that the way they treat freelancers is *also* abysmal. I was almost always given half the time I asked for and paid at less than *half* of my general going rate. Authors publishing out of their own pockets could afford my rate, but apparently multi-billion dollar corporations couldn't. Copy edits and proofreads are often handled by freelancers, meaning these are people who aren't familiar with the author's voice and often give feedback that doesn't account for that, plus they're not people who are gonna be as invested in the book, even before the bad payment and ridiculous timelines.

So, anyway, 1. go easy on authors and editors when you can. Most of us have 0 say in being in this position and authors who are in breech of their contract by refusing to turn in a book on time can face major legal and financial ramifications. 2. Know that this isn't in your head. If you disagree with the choices a book makes, that's probably just a disagreement, but if you feel like it had so much potential but just *didn't reach it*, that's likely because the author didn't have time to revise it or the editor didn't have time to give the sort of thorough edits it needed. 3. READ INDIE!!! Find the indie authors putting in the work the Big 5's won't do and support them! Stop counting on exploitative mega-corporations to do work they have no intention of doing.

Finally, to all my readers who read Café Con Lychee and loved it, thank you. I love y'all, and I appreciate y'all, and I really wish I'd been given the chance to give y'all the book you deserved. I hope I can make it up to you in 2025.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

currently maybe possibly single-handedly crashing whatever servers eton hosts its archived student newspapers on because me and a friend are getting obsessed with a single outspoken prefect from 1883

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

So a couple days ago, some folks braved my long-dormant social media accounts to make sure I’d seen this tweet:

And after getting over my initial (rather emotional) response, I wanted to reply properly, and explain just why that hit me so hard.

So back around twenty years ago, the internet cosplay and costuming scene was very different from today. The older generation of sci-fi convention costumers was made up of experienced, dedicated individuals who had been honing their craft for years. These were people who took masquerade competitions seriously, and earning your journeyman or master costuming badge was an important thing. They had a lot of knowledge, but – here’s the important bit – a lot of them didn’t share it. It’s not just that they weren’t internet-savvy enough to share it, or didn’t have the time to write up tutorials – no, literally if you asked how they did something or what material they used, they would refuse to tell you. Some of them came from professional backgrounds where this knowledge literally was a trade secret, others just wanted to decrease the chances of their rivals in competitions, but for whatever reason it was like getting a door slammed in your face. Now, that’s a generalization – there were definitely some lovely and kind and helpful old-school costumers – but they tended to advise more one-on-one, and the idea of just putting detailed knowledge out there for random strangers to use wasn’t much of a thing. And then what information did get out there was coming from people with the freedom and budget to do things like invest in all the tools and materials to create authentic leather hauberks, or build a vac-form setup to make stormtrooper armor, etc. NOT beginner friendly, is what I’m saying.

Then, around 2000 or so, two particular things happened: anime and manga began to be widely accessible in resulting in a boom in anime conventions and cosplay culture, and a new wave of costume-filled franchises (notably the Star Wars prequels and the Lord of the Rings movies) hit the theatres. What those brought into the convention and costuming arena was a new wave of enthusiastic fans who wanted to make costumes, and though a lot of the anime fans were much younger, some of them, and a lot of the movie franchise fans, were in their 20s and 30s, young enough to use the internet to its (then) full potential, old enough to have autonomy and a little money, and above all, overwhelmingly female. I think that latter is particularly important because that meant they had a lifetime of dealing with gatekeepers under our belts, and we weren’t inclined to deal with yet another one. They looked at the old dragons carefully hoarding their knowledge, keeping out anyone who might be unworthy, or (even worse) competition, and they said NO. If secrets were going to be kept, they were going to figure things out for ourselves, and then they were going to share it with everyone. Those old-school costumers may have done us a favor in the long run, because not knowing those old secrets meant that we had to find new methods, and we were trying – and succeeding with – materials that “serious” costumers would never have considered. I was one of those costumers, but there were many more – I was more on the movie side of things, so JediElfQueen and PadawansGuide immediately spring to mind, but there were so many others, on YahooGroups and Livejournal and our own hand-coded webpages, analyzing and testing and experimenting and swapping ideas and sharing, sharing, sharing.

I’m not saying that to make it sound like we were the noble knights of cosplay, riding in heroically with tutorials for all. I’m saying that a group of people, individually and as a collective, made the conscious decision that sharing was a Good Things that would improve the community as a whole. That wasn’t necessarily an easy decision to make, either. I know I thought long and hard before I posted that tutorial; the reaction I had gotten when I wore that armor to a con told me that I had hit on something new, something that gave me an edge, and if I didn’t share that info I could probably hang on to that edge for a year, or two, or three. And I thought about it, and I was briefly tempted, but again, there were all of these others around me sharing what they knew, and I had seen for myself what I could do when I borrowed and adapted some of their ideas, and I felt the power of what could happen when a group of people came together and gave their creativity to the world.

And it changed the face of costuming. People who had been intimidated by the sci-fi competition circuit suddenly found the confidence to try it themselves, and brought in their own ideas and discoveries. And then the next wave of younger costumers took those ideas and ran, and built on them, and branched out off of them, and the wave after that had their own innovations, and suddenly here we are, with Youtube videos and Tumblr tutorials and Etsy patterns and step-by-step how-to books, and I am just so, so proud.

So yeah, seeing appreciation for a 17-year-old technique I figured out on my dining-room table (and bless it, doesn’t that page just scream “I learned how to code on Geocities!”), and having it embraced as a springboard for newer and better things warms this fandom-old’s heart. This is our legacy, and a legacy the current group of cosplayers is still creating, and it’s a good one.

(Oh, and for anyone wondering: yes, I’m over 40 now, and yes, I’m still making costumes. And that armor is still in great shape after 17 years in a hot attic!)

75K notes

·

View notes

Text

love when im watching a documentary and im like "yep thats an egyptologist alright"

57K notes

·

View notes

Text

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

THERE IS. a website. that takes 3D models with seams and pulls it apart to make a plushie pattern and informs you where things need to be edited or darts added for the best effect. and then it lets you scale it and print off your pattern. and I want to lose my MIND because I've lost steam halfway through so many plushie patterns in the mind numbing in betweens of unwrapping, copying all of the meshes down as pieces, transferring those, testing them, then finding obvious tweaks... like... this would eradicate 99% of my trial and error workflow for 3D models to plushies & MAYBE ILL FINALLY FINISH SCREAMTAIL...

91K notes

·

View notes

Text

47K notes

·

View notes

Text

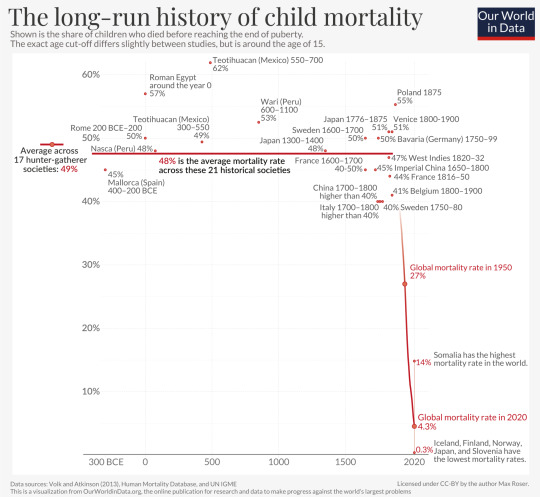

Remember, history was awful. Never trust the romantics.

73K notes

·

View notes