Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

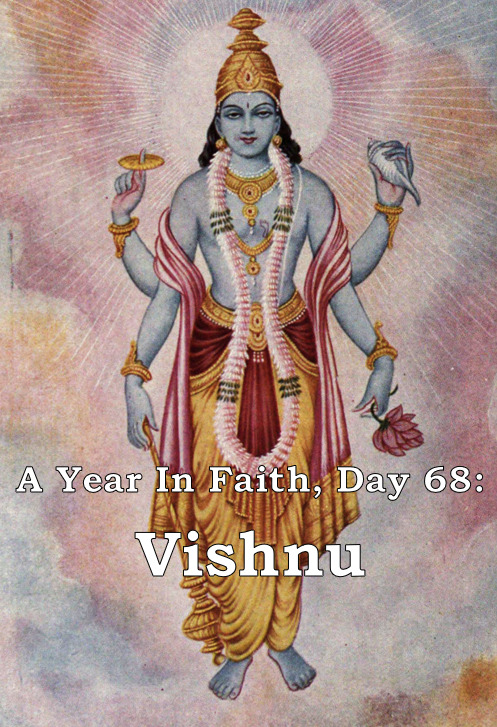

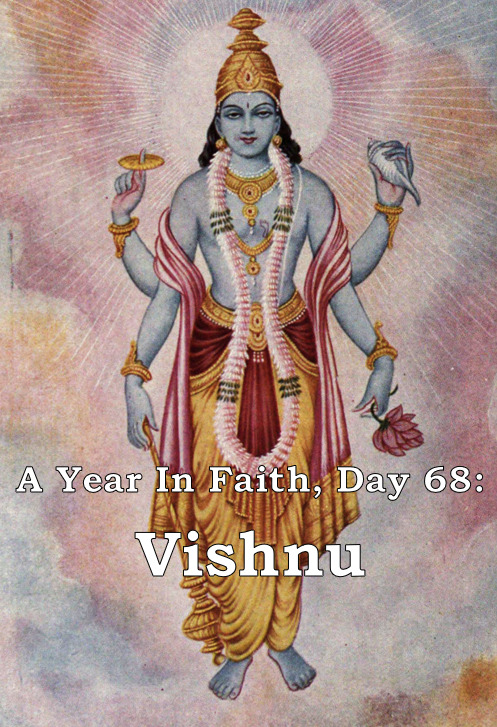

𝗔 𝗬𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝗶𝗻 𝗙𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗵, 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟲𝟴: 𝗩𝗶𝘀𝗵𝗻𝘂

“O ye who wish to gain realization of the Supreme Truth, utter the name of “Vishnu” at least once in the steadfast faith that it will lead you to such realization.” -Foreword by N. Raghunathan to P. Sankaranarayanan’s translation of 𝘚𝘳𝘪 𝘝𝘪𝘴𝘯𝘶𝘴𝘢𝘩𝘢𝘴𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘢𝘮𝘢 𝘚𝘵𝘰𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘮. The quote claims to be from the 𝘙𝘪𝘨 𝘝𝘦𝘥𝘢, possibly hymn 156 of the first book, though if it is, it is not from any standard English translation.

Vishnu is the Hindu god of preservation and is considered to be the supreme deity in Vaishnavism, Hinduisms largest branch. In addition to his supreme status, he is best known in relation to his avatars, which include central figures in the epics 𝘙𝘢𝘮𝘢𝘺𝘢𝘯𝘢 and 𝘔𝘢𝘩𝘢𝘣𝘩𝘢𝘳𝘢𝘵𝘢. The traditional etymology for his name is “all-pervasive”.

𝗔𝗹𝗹-𝗣𝗲𝗿𝘃𝗮𝘀𝗶𝘃𝗲

The name Vishnu is traceable back to the oldest of Hindu scripture and some of the oldest texts in any Indo-European language: the 𝘝𝘦𝘥𝘢𝘴, which date back to around 1500 BCE. In these texts Vishnu is less prominent than figures like Indra (king of the gods) or Agni (god of fire) and Vishnu is portrayed as a god of the heavens, associated with the sky, light, and the sun. His rise to supreme deity likely occurred as a result of the aggressive fusion of several other deities between the 7th and 4thcenturies BCE. Prominent among these were deified tribal folk heroes like Vasudeva and Krishna (still popular in his own right and as an avatar of Vishnu). Both of these figures and others like them were popular and relatable deities who did not come from the Vedic tradition i.e. from various folk traditions as opposed to (at the time) Hindu orthodoxy. An attempt to consolidate these popular beliefs with the already orthodox Vedic establishment brought figures like Narayana, a supreme fusional deity, and Vishnu, the embodiment of heaven, into the fold as well. This development establishes Vishnu’s transcendent supremacy, pluriform nature, and widespread appeal. By the writing of the Hindu epics (roughly 3rd or 4th century BCE) Vaishnavism was well established and able to appeal to Hindu’s of all denominations. In this way Vishnu quite literally lives up to his name, poised to cross the exceptional diversity of Indian religious traditions. Vishnu’s pervasiveness is also relevant to his own, contemporary doctrine. Vaishnavism is a heavily ‘Advaitic’, a descriptive term in Hindu philosophy which literally means “non-dualistic”. What this means is that all of existence is, ultimately, singular and all distinctions between things are illusory. To massively simplify: reality is an illusion and Vishnu represents the singular whole of all things into one. Thus Vishnu is, again, truly all-pervasive.

𝗦𝘆𝗺𝗯𝗼𝗹𝗶𝘀𝗺 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗔𝘃𝗮𝘁𝗮𝗿𝘀

Possibly due to his fusional past, Vishnu is the god most associated with avatars i.e. a mortal incarnation of the deity born into the world in order to fulfill a task of cosmic importance. Though Vishnu is not the only Hindu deity to have avatars, his are core to his worship. There are many figures ascribed to Vishnu’s avatars, but most important is the doctrine of ten avatars aka. The Dashavatara. This cycle tracks Vishnu’s involvement in earthly affairs from the origin of mankind to the future end of days. As this series has already featured an entry devoted to avatars, including the Dashavatara, I will simply link that HERE. Vishnu is often contrasted, or complementary to, a fellow member of the Hindu trinity and supreme god of Hindu’s second largest branch: Shiva, god of destruction (perhaps better rendered as “transformation” to a Western audience). While Shiva actively dances the universe into being, Vishnu dreams it into existence. Shiva is an ascetic, dressed in a tiger’s skin with matted hair, while Vishnu is regal in his fine robes and jewelry. Shaivism (worship of Shiva as the supreme deity) is most common in Dravidian speaking south India, Vaishnavism in Indic speaking north India. Vishnu is most commonly depicted in a four armed form, carrying his four relics: The Chakra called Sudarshana a weapon which has also been deified in its own right, the mace Kaumodaki, representing Vishnu’s age and strength, the conch shell Panchajanya, which Krishna blew to usher in the climactic war of the 𝘔𝘢𝘩𝘢𝘣𝘩𝘢𝘳𝘢𝘵𝘢, and the lotus, the Hindu symbol of transcendence and purity. His mount is the legendary bird Garuda and his bed is the king of Nagas (mythic and/or literal snakes). The devotion of both birds and snakes, warring entities in Hindu cosmology, is a further representation of Vishnu’s all-pervasive, Advaitic nature. In addition to his four armed form, another common depiction is the Vishvarupa, literally the “universal form”. This form often has many faces extending to the left and right and many arms forming a wing-like outline, though the arrangement of heads and arms may vary and sometimes it is simply the form of Vishnu with all of the Hindu universe mapped out upon him. This was the form that famously appears in the 𝘔𝘢𝘩𝘢𝘣𝘩𝘢𝘳𝘢𝘵𝘢, when Krishna reveals to Arjuna that he is an avatar of Vishnu and shows him his true all-pervasive form. Arjuna’s mortal mind cannot process the vision, though is not destroyed by it as is depicted for similar events involving Zeus in Greek mythology, and ultimately the encounter gives Arjuna the clarity of purpose he needs to commit to the righteous war of the 𝘔𝘢𝘩𝘢𝘣𝘩𝘢𝘳𝘢𝘵𝘢. The symbolism of this form is clear: all people, things, and even other gods, all things good and bad, great and small, are part of Vishnu.

Image Credit: From a translation of 𝘔𝘢𝘩𝘢𝘣𝘩𝘢𝘳𝘢𝘵𝘢 by Ramanarayanadatta astri, 1901

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

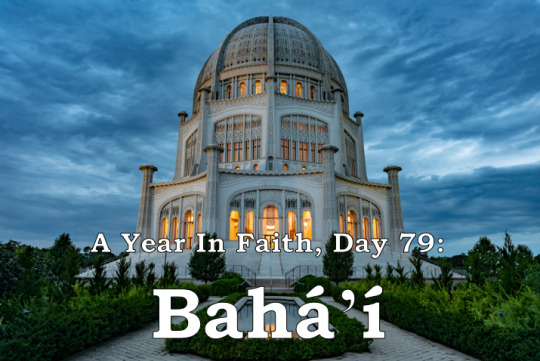

𝗔 𝗬𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝗶𝗻 𝗙𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗵, 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟳𝟵: 𝗕𝗮𝗵𝗮́ʼ𝗶́ Baháʼí is a religion which developed primarily out of Shia Islam in what is now Iran in the late 19th century. Taxonomically, it is an Abrahamic faith, a sister of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, though it holds itself to be part of a grander worldwide tradition of faiths. The word “Baháʼí” became the title of the religion after its primary founder, Baháʼu'lláh, and means “glory” in Arabic. 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗕𝗮́𝗯 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗕𝗮𝗵𝗮́ʼ𝘂'𝗹𝗹𝗮́𝗵 In 1844 a 25-year-old merchant would declare himself a messenger of the singular Abrahamic God and forerunner of the Messiah (a savior figure present to some extent in all Abrahamic faiths). He took the name “Báb”, Arabic for “gate”, as a reference to one of the titles traditionally given to the deputies of the Messiah in Shia Islam. Over the next 6 years the Báb spread his message and accrued a following estimated to be around 100,000 or so across modern-day Iran and Iraq. The Islamic authorities did not take kindly to the rise of what they saw as a heretical faith and, after years of persecution and exile, executed the Báb in 1850. Official records state that his body was left to be eaten by wild animals, though the Baháʼí claim that his remains were secretly smuggled out and now reside at the shrine of the Báb, a Baháʼí pilgrimage site in Haifa, Israel. This did not stop the religious movement, and thirteen years later, in 1863, Baháʼu'lláh made the claim that he was the figure foretold by the Báb. Baháʼu'lláh was a known figure in the religion and had already been influential in developing the doctrine as something distinct from Islam. His claim came with some controversy, though he was not the only person to make it after the Báb’s death. The Báb had given his incomplete writings to Subh-i-Azal, Baháʼu'lláh’s younger half-brother, so that he could complete them. This act was seen by many as a declaration that leadership of the religion fell to Subh-i-Azal. Baháʼu'lláh claimed that, as the foretold manifestation of God, he superseded that claim for leadership. This lead to an internal schism, causing the followers of Baháʼu'lláh to adopt the term “Baháʼí” for themselves, as distinct from other Bábís. Baháʼu'lláh convinced the majority of Baháʼí to his cause, and would further develop core Baháʼí concepts to their, more or less, modern understandings. Baháʼu'lláh passed leadership of the faith to his son, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, who would, in turn, pass it to his eldest grandson, Shoghi Effendi. Shoghi Effendi is largely responsible for the increased globalization of the religion, translating its texts and building movements beyond Greater Iran and adjacent lands. After him, leadership remained within the Universal House of Justice, an organization of elected officials already founded by Baháʼu'lláh which acts as the source of Baháʼí canon and a center for global Baháʼí organization to this day. 𝗣𝗿𝗼𝗴𝗿𝗲𝘀𝘀𝗶𝘃𝗲 𝗥𝗲𝘃𝗲𝗹𝗮𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻𝘀 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗠𝗼𝗱𝗲𝗿𝗻 𝗥𝗲𝗹𝗶𝗴𝗶𝗼𝗻 The core of Baháʼí and ultimate cause of its split with Islam is the concept of the progressive revelation. As a core religious concept, I should note that there is depth to this which I cannot convey in an article this brief, so the following is a severe simplification. The idea is twofold: the first part is that God has not given his truth to the world only once, or even only a few times, but many times over the course of millennia. The second is that each one of these revelations was given in a manner relevant to the people it was given to. Thus, Baháʼí believe that Jesus was a true messenger of God, as was Muhammad, Zoroaster, the Buddha, and others. The difference in their doctrines is that Jesus was given the revelation of God as was needed for first millennia Mediterranean peoples, Buddha the version appropriate for 5th century BCE peoples of Asia, and so on. Each doctrine is the absolute truth of God and, in the eyes of the Baháʼí, contain mostly similar messages. The distinctions between religions are due to the needs and understanding of distinct cultures across space and time. Each revelation builds upon the last and come every 1,000 years, with Baháʼí being the most recent. With this knowledge, Baháʼí see their faith and its beliefs as being very directly relevant and designed around the modern world we live in today, which contrasts to many other faiths who view their principles as eternally relevant. The unity of humanity is a core principle of Baháʼí, which is very specifically anti-racist and anti-colonialist, though in a purely social way as Baháʼí are discouraged from direct engagement in local politics. Other modern religious ideals include the push for worldwide compulsory education, the equality of the sexes, the elimination of wealth inequality, and the use of auxiliary languages for international communication (Baháʼu'lláh himself praised Esperanto). Image Credit: Baha'i Temple in Wilmette, Illinois, taken by Michael Donahue in 2018.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝗔 𝗬𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝗶𝗻 𝗙𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗵, 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟳𝟴: 𝗣𝗲𝗿𝘀𝗲𝗽𝗵𝗼𝗻𝗲 Persephone is the Greek goddess of spring and queen of the Underworld, a personification of the changing seasons. Her name possibly means “grain thresher”. 𝗘𝗮𝗿𝘁𝗵 𝗦𝗵𝗮𝗸𝗲𝗿’𝘀 𝗗𝗮𝘂𝗴𝗵𝘁𝗲𝗿 Persephone is traceable back to the pre-classical Mycenean period of Greek history (1600-1100 BCE). It’s possible she may be even older, from the Minoan civilization, from which we have evidence of a harvest goddess who underwent a cycle of rebirth, though at this point the direct connection becomes tenuous. Persephone is not alone in Mycenae; Linear B (the writing system used before the Phoenician-born Greek alphabet still used today) inscriptions have been found bearing the names of most of the classical panhellenic gods, though with some notable discrepancies. Some 3-8 hundred years before Homer wrote the 𝘖𝘥𝘺𝘴𝘴𝘦𝘺, Zeus was not the chief of the gods. Instead that role was filled by Poseidon. Poseidon himself was also not the sea god, but an underworld deity who had the epithet “earth shaker”. Hades, the classical god of the underworld, was absent. This is relevant to Persephone as she is related to all these gods in significant ways. In classical mythology Zeus is her father, and Hades is her husband. In Mycenae, both these roles seem to have been filled by Poseidon, with Persephone and her mother Demeter (also attestable at that time) filling the role of dual queens. How the change from Mycenae to Homer occurred is uncertain, the two civilizations are separated by a 3-400 year long dark age with sparse records. To speculate, its likely that as Poseidon and Zeus changed roles, the partners of Demeter and Persephone fluctuated to maintain thematic purity. Its important to the myth that Persephone be the daughter of the chief god (a royal divine lineage) and that she be wed to the underworld god (as a cycle of life and death). Transitions of this kind are common, and especially noticeable when myths pass between different cultures; the individuals of the myth may change greatly, but the themes maintain. An important thing to note her is that, in the religious practices of Persephone and Demeter, they are the main actors; not their interchangeable husband/s. 𝗗𝗮𝘂𝗴𝗵𝘁𝗲𝗿 𝗼𝗳 𝗠𝘆𝘀𝘁𝗲𝗿𝗶𝗲𝘀 Persephone is most associated with the ancient Greek religious tradition known as the Eleusinian Mysteries. The mysteries were both an organization and a specific event of initiation rites (aka. “mysteries”) that took place in the sanctuary at Eleusis. The Eleusinian Mysteries were not the only mystery religion of ancient Greece, but they were the most famous, both then and now. Possibly as a result of its popular yet secretive nature the Mysteries had a remarkably stable and long life, stemming from pre-classical times (Mycenean or even Minoan) and persisting until the rise of Christianity and prosecution of Pagans in the Roman Empire. So stable was its doctrine, it even seems to have preserved aspects of the Mycenean arrangement of gods, with the underworld Poseidon. There may even have been a distinct identity given to the earlier and later versions of Persephone, evidenced by epithets: the elder daughter of Demeter and Poseidon, Despoina (“mistress”), and the younger daughter of Demeter and Zeus, Kore (“girl”). At the center of these traditions was the abduction myth. The general story is as follows: Hades, lord of the underworld, falls in love with Persephone. He beseeches her father, Zeus, for permission to marry her. Zeus, aware that Demeter would not allow the union, advises Hades to abduct Persephone. Hades does so, taking Persephone into his domain beneath the earth. Demeter is distraught when she cannot find her daughter and causes the earth to become barren. Zeus commands Hades to return Persephone in order to end the disaster. Hades does so, but not before Persephone eats from a pomegranate. Having eaten the food of the underworld, she becomes bound to it. While she can return to Demeter and bring life back to the world, she must eventually return to the underworld and let the Earth go barren again. The core of the myth is tied to the changing of the seasons: vegetation seems to dies in the winter (in the Northern Hemisphere) and return to life in spring. To initiates of the Eleusinian Mysteries, this cycle of death and rebirth also represented a form of immortality of the soul, though it is uncertain if this was further extrapolated to a doctrine of reincarnation or simply the perception of the continuity of one’s family line as immortality. 𝗗𝗶𝘃𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝗶𝗻𝘁𝗼 𝗔𝗯𝗱𝘂𝗰𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻 At a glance, the abduction myth seems to portray Hades as a villain, stealing a young maiden for lascivious purposes and then trapping her with him. Most ancient records of the myth do generally depict a terrified Persephone during the act of the abduction itself and a duplicitous Hades feeding her the pomegranate. But there are reasons to assume the depiction was not so simplistic, not least of which being that the myth is part of the core doctrine of a religious tradition built upon secret initiations. For context, it should be noted that the underworld is not the Greek equivalent of the Christian underworld, or Hell, which is a nightmarish realm of torture. The Greek underworld is a realm of the dead, but of all dead, virtuous and wicked. Death is also only one of its functions; it is also the source of mineral wealth. Thus, Hades is not a Greek devil, but a kind of fertility god in his own right, the source of precious metals, gemstones, and other such things. The pairing of Persephone and Hades is not a union of opposites, but compliments. When looking at depictions of the underworld couple outside of this myth, they are often the very image of royal respectability, a great contrast to the antagonistic relationship of the actual chief couple Zeus and Hera. Persephone is invoked directly in the 𝘖𝘥𝘺𝘴𝘴𝘦𝘺 when Odysseus descends to the underworld, and his sacrifice is made to her, not Hades. This does not necessarily imply that Hades act was not kidnapping; the characters are, after all, fictional, and the ancient Greeks did not generally feel pressed to explain incongruities in mythology: these were things of gods which humans cannot understand. There is a possibility that the entire affair is a metaphoric depiction of ancient Greek courting rituals in which Zeus or Demeter are at fault; Demeter for being overprotective of Persephone, Zeus for his dishonesty to Demeter. Many Renaissance depictions of the myth use the title “the rape of Persephone”, though this use of “rape” stems from the Latin for “seize” and did not contain the explicit meaning of sexual violence it does now. Image Credit: Proserpine, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1874

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝗔 𝗬𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝗶𝗻 𝗙𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗵, 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟳𝟳: 𝗚𝗵𝗼𝘂𝗹 The ghoul is a monster from Arabic folklore that eats humans. Its name comes from the Arabic for “sieze”. 𝗢𝗴𝗿𝗲𝘀𝘀 Belief in ghouls predates the arrival of Islam in the Arabian Peninsula (6th century CE) and may go back millennia further. The word has been tentatively tied to the Akkadian “gallu” demon. Before the word was introduced into the English language in the 18th century, the word was, and still is, translated as “demon”, “djinn”, or “ogre(ss)”. Tales of ghouls often filled a common mold: the creature would take the form of a human woman, accompany travelers into the desert or lure them there, and then devour them. When not in the form of a human, in which case they are almost always female, they are monstrous but how exactly varies significantly. Sometimes they are like deformed humans, other times outright bestial, and most commonly are hairy and clawed. They are generally not much larger than a human and can be slain, though if done improperly they can return from death, a common variant being that they must be felled in exactly one strike of the sword. With the arrival of Islam, ghouls were contextualized into the religion. Their origin is occasionally given as a class of fallen angel, who burned up into deformed creatures as they fell to earth. They also gained a new weakness: prayer. Proper invocation of the prophets can repel or outright destroy ghouls, similar to the impact of Christian icons on a European Vampire. 𝗭𝗼𝗺𝗯𝗶𝗲 While the classical Arabic ghoul is a devourer of humans, it generally is depicted as seeking live prey. When the legend was transmitted to Europe, the ghoul shifted to become more of a scavenger, haunting graveyards and feasting on cadavers. This is generally attributed to the early 18th century translation of 𝘖𝘯𝘦 𝘛𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘴𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘖𝘯𝘦 𝘕𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵𝘴 by the French Antoine Galland. 𝘖𝘯𝘦 𝘛𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘴𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘖𝘯𝘦 𝘕𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵𝘴 was not a single specific work, but a compilation of Islamic Golden Age tales compiled, recompiled, and retold by many sources, so it is not surprising that Galland took liberties with the subject matter. How much is uncertain, as some of his claimed sources were transmitted verbally. Regardless, in his version ghouls had developed a taste for corpses and were associated with hyenas (a scavenging animal). This association with eating corpses led “ghoul” to be the original term used for the shambling undead creatures from the 1968 film 𝘕𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘓𝘪𝘷𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘋𝘦𝘢𝘥, though the Haitian term “zombie” would quickly replace it. Image Credit: 𝘗𝘪𝘤𝘬𝘮𝘢𝘯’𝘴 𝘔𝘰𝘥𝘦𝘭 by Dave Kendall

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝗔 𝗬𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝗶𝗻 𝗙𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗵, 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟳𝟲: 𝗟𝗲𝗽𝗿𝗲𝗰𝗵𝗮𝘂𝗻 "The rogue was mine, beyond a doubt./ I stared at him; he stared at me;/ 'Servant, Sir!' 'Humph!' says he,/ And pull'd a snuff-box out./ He took a long pinch, look'd better pleased,/ The queer little Leprachaun;/ Offer'd the box with a whimsical grace,—/ Pouf! he flung the dust in my face,/ And while I sneezed,/ Was gone!" -𝘙𝘩𝘺𝘮𝘦𝘴 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘠𝘰𝘶𝘯𝘨 𝘍𝘰𝘭𝘬; 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘓𝘦𝘱𝘳𝘢𝘤𝘢𝘶𝘯 𝘖𝘳 𝘍𝘢𝘪𝘳𝘺 𝘚𝘩𝘰𝘦𝘮𝘢𝘬𝘦𝘳, William Allingham, 1886 The Leprechaun is small supernatural human-like creature from Irish folklore, generally classified as a type of Fairy. The name is generally thought to mean “small body” though a common folk etymology is that is means “half brogue”, implying the Leprechaun’s relations to shoemaking. 𝗟𝗲𝗽𝗿𝗲𝗰𝗵𝗮𝘂𝗻: 𝗢𝗿𝗶𝗴𝗶𝗻𝘀 Prior to the 19th century there is very sparse attestation of the Leprechaun, though they do appear in the 8th century tale 𝘌𝘤𝘩𝘵𝘳𝘢 𝘍𝘦𝘳𝘨𝘶𝘴 𝘮𝘢𝘤 𝘓𝘦́𝘵𝘪. In the tale, the eponymous king Fergus goes to sleep on a beach, awakening to find himself being dragged into the ocean by three Leprechauns (in this text spelled “lúchorpáin” and sometimes translated into English as “dwarf”). Fergus is able to best the diminutive creatures (they are not described in any more detail) and they bargain with him for their freedom, offering three wishes which Fergus accepts. The development of the legend for the next thousand years is sparsely attested, though the granting of wishes once captured persisted. The Leprechaun comes back with force in the 19th – 20th centuries, likely popularized in part by the Irish poet W.B. Yeats, who was himself likely much inspired by the earlier poetry on the topic by William Allingham. These poets depicted small capricious Fairies with the appearance of old men wearing outdated Victorian-style outfits, associated with shoemaking, buried treasure, and the granting of wishes. The appearance of the Leprechaun may have come about by fusion with similar Germanic household spirits; the Scandinavian Tomte or Nisse, for example, also explicitly take the form of old men in outdated clothes and are often depicted making shoes. A similar creature also appears in literature around this same time: the Clurichaun. The Clurichaun (who name may come from “clover head”) is similar to the Leprechaun in form and also possesses secret gold. While Leprechauns are secretive and deceptive, Clurichauns are depicted as heavy drinkers and overtly antagonistic to humans with whom they cross paths. It’s uncertain if the Clurichaun legend precedes the 18th century, and if it is related to the Leprechaun or not, though overt similarities have caused the two to fuse in many subsequent versions. 𝗠𝗼𝗱𝗲𝗿𝗻 𝗟𝗲𝗽𝗿𝗲𝗰𝗵𝗮𝘂𝗻𝘀 The origin of the Leprechaun’s gold is uncertain, though it may be related to Irish myths of buried treasure left by Viking raiders. The pot of gold at the end of the rainbow likely stems from an allegory for the unattainable nature of the treasure; the end of the rainbow cannot be reached as it is an optical illusion, not a real thing. Leprechaun lore often holds that they have two coins on them; one silver and one gold, both of which will disappear once taken from the creature. Modern Leprechauns wear green, as they have become a symbol of Ireland (where green is the national color), but the versions reported by Allingham, Yeats, and other contemporary poets/folklorists wore red or other colors depending on what part of Ireland they were from. In Ireland, Leprechaun-sightings currently occupy a similar cultural niche in many ways to the American sighting of a Bigfoot or other regional cryptid, and Leprechaun hunting (normally involving hidden candy or toys) is a common children’s activity in certain parts of the country. As it has risen to be a recognized national symbol abroad, the Leprechaun is also associated with tourist culture in Ireland i.e. trivial and over-marketed. Some depictions of the Leprechaun, especially those with domed hats of the kind common to 19th century Irish-American immigrants and with Clurichaun-like drinking habits, have been decried by some as offensive stereotypes, though this does not apply to all depictions (ex. There has never been any widespread outrage against the widely recognizable Leprechaun mascot for Lucky Charms cereal). Image Credit: Teeney O’Feeney, Larry MacDougall, 2008

1 note

·

View note

Photo

𝗔 𝗬𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝗶𝗻 𝗙𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗵, 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟳𝟱: 𝗦𝘄𝗮𝘀𝘁𝗶𝗸𝗮 The swastika is a common symbol found across the world and throughout history, ascribed with many meanings, though its popularity among Western cultures sharply declined with its association to Nazis in the second world war. The word “swastika” entered the English vocabulary in the 19th century, replacing the former “grammadion” (short for Greek “tetragrammadion” i.e. “four letter gammas”) or “fylfot” (etymology uncertain). “Swastika” comes from Sanskrit for “well-being”. 𝗛𝗶𝘀𝘁𝗼𝗿𝗶𝗰𝗮𝗹 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗠𝗼𝗱𝗲𝗿𝗻 𝗧𝗿𝗮𝗱𝗶𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻𝘀 The earliest known swastika is a 10,000 BCE carved mammoth bone discovered in what is now Ukraine. It was known to be in use among the ancient Proto-Indo-European people (who spread forth from Ukraine and Southwest Russia between 6-4000 BCE), who brought it with them in their migrations, though it is unlikely they invented or were even the first to bring the symbol to various parts of Eurasia. They symbol comes up frequently in the archaeological record, first appearing in South Asia around 3000 BCE. The swastika is a prominent symbol in Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism, and related usage spread across the rest of Asia. In Europe the swastika was a very poplar motif in Greek and Roman art, and was a common symbol used to invoke various thunder gods (Thor, Perun, Zeus, etc). Christians adopted it easily as it looks similar to a crucifix and, like elsewhere, it was used more generically as a symbol of good luck and remained in popular use in churches, military insignia, and art right up until the second world war, especially in Eastern Europe. In South Asian the symbol became iconic in Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism. South Asian swastikas typically bend to the right (卐) and are oriented on the square. While they still serve a generic symbol for fortune, in Hinduism it can also serve as a specific sign for the god Indra (another thunder god), and the sun. The left bending swastika (卍) is associated with the Tantric tradition and the goddess Kali. For Jains it is often representative of the Tīrthaṅkara, a savior or enlightenment figure somewhat similar to the Buddhist Buddha. In that same vein, in Buddhism it is an aniconic representation of the Buddha, often credited as Buddha’s footsteps. In East Asia the left bending swastika (卍) is the norm and is a recognized character of the Chinese character system. It is an alternate form of “萬” or “万”, which means “10,000”. Like the Greek equivalent, “myriad”, this number is a common metaphor for the totality of things. Because of its association to Buddhism, swastikas are common map markers in parts of East Asia for Buddhist temples and in some cases a sign for vegetarian or vegan safe food. Outside of Eurasia, swastikas are/were particularly popular among indigenous people of the American Southwest, and was proudly displayed on Arizona road markers before WWII. 𝗔𝗿𝘆𝗮𝗻𝗶𝘀𝗺 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗡𝗮𝘇𝗶𝘀 The complete reversal and subsequent erasure of swastika symbolism in the West begins with a seemingly unrelated, but historically significant event: the rediscovery of the city of Troy. Heinrich Schliemann was a 19th century German businessman and self-styled archeologist. He was obsessed with Homer’s 𝘐𝘭𝘪𝘢𝘥, the ancient Greek tale of the battle of Troy (aka. Ilios). At the time, and in fact since antiquity, most people believed the 𝘐𝘭𝘪𝘢𝘥 to be simply a legend and Troy a fictional place. Schliemann believed it to be a mythologized account of a real battle and set out to prove it. Against all odds, he turned out to be correct and stumbled upon the remains of Troy in what is now western Turkey. Not just the Troy of Homer, but in fact the buried bones of many generations of ancient cities on that site. And among the relics, around 1,800 documented swastikas. This caught the eye of the growing Aryanism movement. Aryanism developed from pseudo-intellectualism based on the, at the time, new idea of Proto-Indo-European ancestry. Linguists and Anthropologists of the time had just begun to gather real evidence of the common linguistic and cultural ancestors to peoples from Europe to South Asia, and the current reconstructed Proto-Indo-European was still basically just Vedic Sanskrit (this is no longer the case). “Aryan” is used in the Vedas as a self-designation, and is the direct ancestor of the name of the country Iran; to this day linguists still commonly use “Aryan” as a term for the languages of Greater Iran (Farsi, Pashto, Kurdish, etc.). European racists co-opted these developments, building on pre-existing racist/nationalistic ideas of racial purity. In their reckoning, there was once a pure Aryan race, as recorded in the 𝘝𝘦𝘥𝘢𝘴, which then dispersed and intermingled with other races to their collective detriment. Ironically, Aryanists pushed back against the growing theory that Proto-Indo-Europeans came from the Pontic Steppe in Ukraine and Russia (which is what modern scientists believe) instead placing the homeland in Norther Europe, likely because the commonly paler skin and lighter hair and eyes of those people was perceived as being less “interbred” with the darker skinned and haired peoples of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Thus, when Schliemann discovered the Troy of ancient myth, and among it many swastikas, Aryanists claimed they must have been symbols of the “pure Aryan race”. The swastika became very popular among supremacist groups in Europe, eventually landing in the hands of Adolf Hitler. The Nazi swastika is normally a right bending one, and oriented on the diagonal. 𝗕𝗲𝘆𝗼𝗻𝗱 𝗛𝗮𝘁𝗲 The impact and mainstream cultural rejection of Nazism was so potent that most Westerners are shocked by evidence of the common and pleasant use of the swastika in their own countries prior to WWII. The symbol was completely outlawed in post-war Germany and remains so today, though there are exemptions for religious use and for explicitly anti-fascist usage (such as a crossed-out swastika). Though few other Western powers went as far as Germany, usage was largely ceased and buried outside of hate groups. Even indigenous communities, as depicted in the title image of this post, willingly ceased using the symbol. The rest of Asia did not see the same rejection. In part this is likely due to a disconnect from the Nazis, who primarily invaded and fought other European powers. It is also possible that the swastika was more resilient for its direct association to institutions, like Buddhism, that it lacked in the West where it was a more generic symbol. The divide continues, periodically, to cause cultural misunderstandings. Image Credit: Two Navajo Women, Florence Smiley and Evelyn Yathe, sign a decree sponsored by the Navajo, Hopi, Apache, and Tohon O’odham nations promising to no longer use the symbol. International News Photo, February 28, 1940.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝗔 𝗬𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝗶𝗻 𝗙𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗵, 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟳𝟰: 𝗣𝗿𝗼𝘁𝗼-𝗜𝗻𝗱𝗼-𝗘𝘂𝗿𝗼𝗽𝗲𝗮𝗻 𝗥𝗲𝗹𝗶𝗴𝗶𝗼𝗻 The Proto-Indo-European (PIE) religion is the proposed reconstruction of the beliefs held by the ancestral Proto-Indo-Europeans. Though we lack direct evidence for it, the echoes found across the historical record and in modern Indo-European peoples enable us to make strong conjectures about this ancient faith. Names and words in PIE are generally prefixed with a “*-“ to represent their theoretical status. 𝗪𝗵𝗼 𝗧𝗵𝗲𝘆 𝗪𝗲𝗿𝗲 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗛𝗼𝘄 𝗪𝗲 𝗞𝗻𝗼𝘄 The Proto-Indo-Europeans lived as a (more-or-less) single people roughly 6-7 thousand years ago in what is now Southwestern Russia and Eastern Ukraine. They were some of the first humans to domesticate the horse and spread across Eurasia from Europe’s Iberian Peninsula to the South Asian Ganges Delta. Modern Indo-European peoples include but are not limited to: Non-Dravidian people of the Indian sub-continent (Bengalis, Nepalis, Hindustanis, Punjabis, etc.), Persians (aka. Iranians), Kurds, Greeks, Balts (Lithuanians and Latvians), Armenians, Albanians, Slavs, Germans (Scandinavians, Netherlanders, Englishmen, etc.), Celts, and Western Europeans (French, Spaniards, Italians, etc.). The study of these ancient ancestors is the result of a great marriage of physical and linguistic anthropology. On their own, each source of evidence has major blind spots; physical anthropology can only trace what artifacts have survived, especially tricky with an ancient nomadic people who used stone and other long lasting materials sparingly, and linguistic reconstruction is a completely theoretical activity in the absence of any recorded language. By pairing common word origins, we can tell what technology and concepts were common (ex. Almost all branches share the etymology for “wheel” but not for “sword”) which can inform the minimal archaeological finds, which can in turn inform linguists which proposed reconstructions are more likely than others. Just as we can use these tools to determine their technology and migrations, we can guess at more immaterial things like culture and beliefs. Major pillars of this are the 𝘝𝘦𝘥𝘢𝘴 and to a lesser extent the 𝘈𝘷𝘦𝘴𝘵𝘢, the oldest written texts in Indic and Aryan culture, respectively, both of which were written in a language quite similar to Proto-Indo-Aryan (Sanskrit and Avestan), which was spoken some 3-4 thousand years ago. Germanic mythology is another strong pillar, valuable due to being well attested and written about, as Germanic peoples were one of the last of Europe to Christianize. Though Greek mythology has been popular across Europe since the Roman Empire, it is a weak pillar for reconstruction as many of its elements are traceable to non-Indo-European sources (mostly Semitic). Baltic mythology is also prized, as the Baltic languages are the most conservative, i.e. most similar to PIE, but recorded pre-Christian myths are sparse. 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗖𝗼𝗿𝗲 𝗠𝘆𝘁𝗵𝘀 The following is a general overview of some of the most widely agreed upon aspects of PIE religion. There was, before the creation of the universe, a state of non-existence or void (Greek “Chaos”, Norse “Ginnungagap”). After that come three figures: the primordial cow, the progenitor of humankind, *Manu, and a third being *Yemo. The word *Yemo means “twin” (compare to Norse “Ymir”, Hindu “Yama”, and Latin “Remus”). This is generally taken as his relationship to *Manu, but also quite probably is an allusion to *Yemo’s hermaphroditic nature. Likely *Yemo was some form of giant or supernatural being, a cosmic man as opposed to the literal man *Manu. *Yemo is sacrificed along with the cow by *Manu, and from his body the world is formed. It is likely that *Yemo’s myth continues with him as the lord of the land of the dead. The world of the Proto-Indo-Europeans was a flat disk surrounded by water, with the realm of the gods above and that of the dead either below or beyond the world surrounding ocean. Notably, there was likely not a central world tree or mountain, like the Norse Yggdrasil, Greek Olympus, or Hindu Meru; that is most likely a Uralic (Finnish, Hungarian, Udmurt, etc.) loan. The land of the dead was guarded by a supernatural dog (Greek “Cerberus”, Hindu “Sharvara”, Norse “Gamr”). PIE gods have two defining features; their association with the sky and their immortality, which likely was originally credited to a special diet (Hindu “Amrita”, Greek “Ambrosia”, the Norse Idunn’s apples or Odin’s wine). The central gods were *Dyḗus, god of the daylit sky, *Dhéǵhōm, the earth goddess, and their three children, twin sons, who likely represent the sun and moon, and their daughter *Héusōs, goddess of the dawn. The number three is also of special significance and there was likely a triple-fate goddess (Norse “Norns”, Greek “Klothes”), though this is notably absent in the Indo-Aryan branch. The two best reconstructed narratives are the “Chaoskampf”, in which *Dyḗus or his chosen hero slays a serpent, and the cattle raid myth, in which the primordial cow is stolen and must be retrieved through combat by a hero. 𝗢𝘁𝗵𝗲𝗿 𝗧𝗵𝗲𝗺𝗲𝘀 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗧𝗵𝗲𝗼𝗿𝗶𝗲𝘀 As mentioned above, the number three was likely an auspicious number to the Proto-Indo-Europeans. A somewhat less well attested, but still popular reconstruction, is the character of *Trito (“Third”) who would have been the hero who rescues the primordial cow and slays the serpent. This idea of threes was expanded by a French mythographer and linguist, Georges Dumézil in 1929 into what is now referred to as the trifunctional hypothesis. The idea was that PIE society had three classes, which was reflected in their myths; a priestly/scholarly class, a military class, and a herding/farming class. While the theory overall has largely fallen out of favor, aspects of it persist. Many of the mythical battles, like the Norse Æsir-Vanir war or the Greek Titanomachy, have been proposed as mythologized accounts of conflicts or integrations of these three parts. Another tripart proposition is that the PIE cosmos was divided into three skies; the daylit sky, the night sky, and the liminal sky of dawn/twilight. In this model, each sky has its own deities who may not trespass on each other, with *Dyḗus the god of the daylit sky representing the warrior class, *Werunos (compare to Greek Ouranos and Hindu Varuna) god of the night representing the priestly, and a liminal god associated with agriculture (ex. The Greek Kronus, a harvest god who falls between Ouranos and Zeus). Distinctive from *Dyḗus, a hammer wielding storm god has been proposed, though evidence is limited to just a few of the European branches, implying he was likely a later development. His name is reconstructed as *Perkwunos, the “lord of oaks”, likely referencing the way lightning strikes tall trees. Image credit: The Seven Gods, Maxim Sukharev, 2010’s

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝗔 𝗬𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝗶𝗻 𝗙𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗵, 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟳𝟯: 𝗢𝗱𝗶𝗻 “I know that I hung on a wind-rocked tree/nine whole nights/with a spear wounded, and to Odin offered/myself to myself/on that tree, of which no one knows/from what root it springs./Bread no one gave me, nor a horn of drink/downward I peered/to runes applied myself, wailing learnt them/then fell down thence.” - 𝘏𝘢́𝘷𝘢𝘮𝘢́𝘭, stanza 138-9, as translated by Benjamin Thorpe Odin is the chief of the Norse gods, known in other Germanic languages as Woden, Wuotan, and the like. He is the namesake of the English weekday “Wednesday”. His name means “lord of the frenzied”. 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗢𝘂𝘁𝗹𝗶𝗲𝗿 𝗚𝗼𝗱 The earliest records of native Germanic religion, with Odin as chief deity, come from 1st century Roman records. The Roman’s took after the Greek tradition of conceiving the gods of foreign peoples as different versions of their own. Thus, the Roman’s refer to Odin as the “Germanic Mercury”. To those familiar with Roman and Germanic lore, this may seem an odd comparison. Odin is the chief of his pantheon, associated with wisdom, warfare, and magic, while Mercury is a messenger god associated with healing. Understand, the options were limited: the major gods Jupiter (storm and sky) and Mars (war) were already clear choices for Thor (storms) and Tyr (war). In fact, the Romans may have unwittingly stumbled upon a peculiar feature of Odin; he doesn’t seem to fit in the Indo-European religious family. By contrast, Thor, Odin’s son, has readily apparent cousins all across the Indo-European spectrum (ex. the Greek Zeus, Hindu Indra, Slavic Perun), all members of the Sky Father archetype. There is a commonly accepted etymological link between the name of the clan of gods to which Odin belongs, the Æsir, and a Hindu denomination of supernatural being, the Asuras. Both words are generally thought to come from a common Indo-European root meaning something like “life force”, though there are also theories that the root is actually a loan from the Uralic languages (ex. Finnish, Hungarian, Udmurt). If true, it could imply that Odin, and the two-clan division of Norse gods, is actually a loan from Uralic cultures, and it would make Odin a closer relative of the Finnish Väinämöinen than any other European divinity. The slow to Christianize Scandinavians also made a connection of their own, comparing Odin’s self-sacrifice on the world tree (more on this later) to the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. 𝗪𝗶𝘀𝗱𝗼𝗺 𝗦𝗲𝗲𝗸𝗲𝗿 Modern attributions often give Odin the title of “god of war”, though that would more accurately fall to a separate member of the same pantheon; Tyr. Odin presides over many forces including magic, poetry, battle, and death, but above all he is mostly renowned for the seeking and dispersal of wisdom. Some of the most striking imagery of Odin is related to this. His single eye is the price paid in order to drink from the well of wisdom. His ravens keep him aware of all things happening in the world. Even the world tree is named for this: “Yggdrasil” is “Odin’s (Ygg is one of his many names) Horse”, horse being a common allusion to gallows. This is a reference to one of the more striking scenes of the Norse canon, in which Odin hangs himself, after impaling himself on his own spear, from the world tree for nine days in order to die and gain the knowledge of the dead. Knowledge of the dead, in this context, is specifically that of runes, which in Norse culture are both emblematic of writing (and thus academia and poetry) and also of mysticism. Odin’s use of magic is in itself indicative of his dedication; the use of magic was considered a feminine trait and Odin, the divine patriarch himself, is willing to disrupt cultural norms for knowledge. One of the major sections of the poetic 𝘌𝘥𝘥𝘢 (a primary source of Norse canon previously covered in this series) is the 𝘏𝘢́𝘷𝘢𝘮𝘢́𝘭, “Words of the High One (Odin)” which is a series of proverbs and poems attributed directly to Odin, intended as educational philosophy. 𝗜𝗺𝗮𝗴𝗲𝗿𝘆 Odin is traditionally depicted either as a general on his horse or a cloaked wanderer. This second depiction, as a bearded man with a wide brimmed hat and a staff (representing either his magic wand or spear) full of wisdom and obscuring his true power, may seem familiar to readers of modern fantasy as a textbook wizard. This is not coincidence. Most modern versions of wizards borrow heavily from one specific wizard: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Gandalf, who was inspired by the wandering Odin. Odin has a host of animal companions, the aforementioned ravens, Huginn and Muninn (lit. “thought” and “memory” who bring him news, the wolves Geri and Freki (lit. “greedy” and “ravenous”), and the eight-legged, and thus twice as good as regular, horse Sleipnir (lit. “slippery”). In addition to the animals, Odin is also often depicted with the preserved head of the god Mimir, also a wisdom god, with whom Odin consults. Odin wields the spear Gugnir (lit. “swaying”), which could hit any target it was thrown at and possesses a gold ring, Draupnir (lit. “dripper”) which replicated itself nine-fold every nine nights. The numbers three and nine (aka. three groups of three) were considered sacred in ancient Germanic cultures, which is likely the source of one of Odin’s most recognizable symbols, the valknut, which depicts three interlaced triangles. Image Credit: Odin som vandringsman (“Odin in the guise of a wanderer”), Georg von Rosen, 1886.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝗔 𝗬𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝗶𝗻 𝗙𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗵, 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟳𝟮: 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗧𝗼𝘄𝗲𝗿 𝗼𝗳 𝗕𝗮𝗯𝗲𝗹 “And the whole earth was of one language and of one speech. And it came to pass, as they journeyed east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar; and they dwelt there. And they said one to another: 'Come, let us make brick, and burn them thoroughly.' And they had brick for stone, and slime had they for mortar. And they said: 'Come, let us build us a city, and a tower, with its top in heaven, and let us make us a name; lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.' And the LORD came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of men builded. And the LORD said: 'Behold, they are one people, and they have all one language; and this is what they begin to do; and now nothing will be withholden from them, which they purpose to do. Come, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech.' So the LORD scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth; and they left off to build the city. Therefore was the name of it called Babel; because the LORD did there confound the language of all the earth; and from thence did the LORD scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth.” - Genesis 11:1-9, JPS 1917 translation. The Tower of Babel is a legendary structure in Judaism, Christianity, and, to a lesser extent, Islam, whose construction explains the origins of human languages. The traditional etymology of the word is given in the text itself as being from the Hebrew “bālal” (“בָּלַ֥ל”) meaning “to confuse”. 𝗜𝗻𝘁𝗲𝗿𝗽𝗿𝗲𝘁𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗟𝗲𝗴𝗲𝗻𝗱 The quoted text at the start of this post is, in fact, the entirety of the Babel legend as it exists in the Torah and Bible. Many of the other significant attributes, such as the tyrant Nimrod and the cause of God’s actions, are interpretations that stem largely from the 1st century CE Roman Jewish historian Titus Flavius Josephus. Nimrod is mentioned in the previous section of the Torah, in Genesis 10:8-9, a part of the listing of the descendants of Noah. In this, Nimrod is the great-grandson of Noah, via Cush and Ham, whose kingdom contains the cities Babel (Babylon), Erech (Uruk), Akkad, and Calneh, all in the land of Shinar. He is described three times as mighty and twice as a “hunter before the Lord”. It’s this line that leads Josephus and later scholars to paint Nimrod as a villain, interpreting “before the Lord” to mean “against the Lord”. Josephus posits that Nimrod’s cause for building the tower was as a defense against another flood like the kind that wiped out all of mankind save for Noah just a few generations prior. Other scholars instead describe it as an attempt to reach heaven, or a deliberate monument of defiance to God. Still others assign the simple hubris of a tyrant, enslaving his people to build a testament to his own glories. In the Islamic tradition he is often depicted as defender of pagan ways in defiance of the monotheistic patriarch Ibrahim (Abraham in Judaism and Christianity). Regardless, for his crimes God causes his people to all begin speaking different languages, rendering them incapable of collaborating to complete the tower, which is never explicitly destroyed. 𝗖𝗼𝗻𝗳𝗼𝘂𝗻𝗱𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝗼𝗳 𝗧𝗼𝗻𝗴𝘂𝗲𝘀 More so than the tower, the core of the legend, which comes immediately after the enumeration of Noah’s descendants (i.e. The ancestors of all the current peoples of the earth by biblical reckoning), is an explanation for how the peoples of the earth came to be divided, speaking different languages and practicing different cultures. Most modern interpretations follow, again, that of the 1st century Josephus: a punishment for crimes against God. However, there are some less antagonistic versions. Most of these revolve around the idea that mankind was never meant to focus in one place and belabor under one king, and thus, by confounding the language of Babel, God is metaphorically pushing the grown child out of the nest, forcing humankind to expand and diversify. Curiously, in the preceding part of Genesis, the same section in which Nimrod is listed amongst the descendants of Noah, several times the descendants are explicitly listed as having gone of to their own lands, nations, and tongues, which makes the Babel legend either a contradiction, or only the confounding of a subset of human languages. As 72 descendant lines of Noah are explicitly listed in Genesis 10 (though some versions list only 70, or 73), the concept of 72 languages, or at least 72 language families, was popular in Europe through the middle ages, and still referenced well past the Renaissance (though by this time it was seen, at best, as a metaphor). 𝗛𝗶𝘀𝘁𝗼𝗿𝗶𝗰𝗶𝘁𝘆 The origin of the Babel legend as we know it likely comes from 6th century BCE, during or shortly after the period of Jewish Babylonian Captivity. This would explain the naming of the tower: Babel is also the Hebrew word for Babylon, which, despite the legend’s own claims, is simply the Hebrew approximation of the native Akkadian “Bābilim” (“𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠”), meaning “gate of the gods”. This also sets a likely subject for its inspiration: the ziggurat Etemenanki, which was originally constructed in the second millennium BCE but famously reconstructed in Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar II, during the Babylonian Captivity period. What prior legends, if any, evolved or fused into Babel is unknown. We have only fragmentary attestation to somewhat similar stories from the region. One is a Sumerian legend dated to the 21st century BCE, in which the Sumerian king of Uruk, Enmerkar, engages in a strange series of conflicts with a foreign state called Aratta. In this tale, the tower is a grand temple that Enmerkar wishes to build with the blessings of the gods, and is opposed by the King of Aratta who also wishes to build such a temple though he lacks the god’s blessings. The god Enki (covered previously in this series) is invoked to change the tongues of men in the region, though it is uncertain if the text intend Enki’s power to be a Babel like threat against Aratta (i.e. “I will confound the tongues of your people”) or if it is a claim that Enmerkar will unite the peoples against Aratta (“we will all become one people with a common language”). Another, even more incomplete text, comes from the 8th century BCE (much closer to the 6th century origin of the Hebrew legend), which mentions Babylon, as well as a great structure (presumably a tower), and the confounding of languages, though the incomplete text make the narrative impossible to truly reconstruct. Most modern depictions of the tower are based off of two paintings by the 16th century painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder (one of which serves as the title art for this very article). Bruegel based his interpretation on the Roman Coliseum, as both a familiar example of the majesty and ruin of the ancients, and because the fall of the Roman empire at the time was attributed to hubris and Paganism (not to mention the Romans paralleled the Babylonians as biblical oppressors of the Jews). Image Credit: 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘛𝘰𝘸𝘦𝘳 𝘰𝘧 𝘉𝘢𝘣𝘦𝘭, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, c. 1568

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

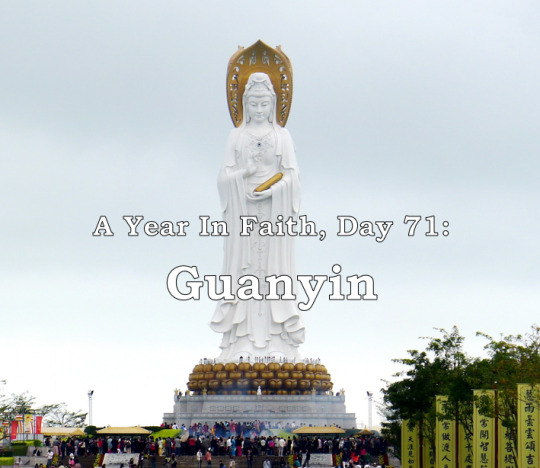

𝗔 𝗬𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝗶𝗻 𝗙𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗵, 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟳𝟭: 𝗚𝘂𝗮𝗻𝘆𝗶𝗻 Guanyin is the distinctive Chinese form of the bodhisattva of compassion, who in India is Avalokiteśvara and Kannon in Japan. In the west she is also known as the goddess of mercy, and is possibly the most popular Buddhist deity in East Asia. Her name means (approximately) “the one who hears the cries of the world”. 𝗙𝗿𝗼𝗺 𝗜𝗻𝗱𝗶𝗮 𝘁𝗼 𝗖𝗵𝗶𝗻𝗮 In theory, the names Guanyin and Avalokiteśvara should be completely interchangeable, and Buddhist tradition across Asia is consistent in equating the two. In practice, however, there are a number of distinctions that hint at a unique character between the two. Most striking of these distinctions is gender; Avalokiteśvara is a male bodhisattva while Guanyin is very feminine. This gap is not hard to bridge in Buddhist cosmology: bodhisattvas are generally considered to have advanced beyond sex or gender, having asexual/androgynous forms and the ability to manifest as anyone or anything. That said, in iconography they are generally much more consistent, and only Guanyin among the pan-Buddhist figures has such a distinctive regional presence. The historical cause of this is uncertain, likely theories posit either that Avalokiteśvara’s nature as a compassionate savior type figure clashed with traditional Chinese gender roles, thus prompting the switch, or that Guanyin is actually a fusional deity, incorporating one or more local goddesses into the Buddhist fold. This second theory is strengthened by the political nature of Chinese Buddhism around the 12th century, when iconography of Guanyin swapped from the Indian style male Avalokiteśvara to the now popular female form. By this time Buddhism had been a part of the Chinese religious landscape for a thousand years, but was still largely viewed as a foreign and minority religion which was not competitive with native Taoism, Confucianism, or Chinese folk-religion. The Song dynasty was the first major state power to openly embrace Buddhism and actively syncretize it with native Chinese elements as a means to establish cultural and political unity in the dominion. 𝗚𝗼𝗱𝗱𝗲𝘀𝘀 𝗼𝗳 𝗠𝗲𝗿𝗰𝘆 The Buddhist universe is largely one of suffering, wherein even death cannot free oneself from the cruelties of our physical world. In opposition to other Chinese religions, which often focus on the importance of societal bonds, Buddhism values the capacity to detach oneself and Buddhist deities or, more accurately, enlightened beings, are often depicted in impersonal or ascetic ways. Guanyin is a significant departure in this respect, as a figure who has forgone escape from the cycle of reincarnation in order to help all living things. One of her popular depictions, Guanyin of the Thousand-Arms, depicts her with numerous arms and heads, depicting her splitting herself in order to help all the myriad souls trapped in the physical world. She is more willing to interfere in the affairs of mankind than other buddhas and bodhisattvas, and thus a very popular subject for prayer. As Avalokiteśvara, she is closely associated with Buddhism’s most well-known mantra (“Om mani padme hum”) which comes from a 4th century text praising Avalokiteśvara as the supreme being. She appears as a supporting character in many legends, notably the epic 𝘑𝘰𝘶𝘳𝘯𝘦𝘺 𝘵𝘰 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘞𝘦𝘴𝘵 in which she collects and guides the pilgrims on their journey. When Christianity was outlawed in Japan, Japanese Christians used figures of Guanyin (Kannon) holding a child to represent the Virgin Mary. She is often depicted wearing lose white robes, seated atop a lotus blossom symbolizing purity and enlightenment. In her hands she often carries a vase, which contains purifying water, and a willow branch, a tool used to sprinkle said water. She is commonly attended by two children, a girl and a boy, and sometimes also a parrot or dragon, all figures from the legend of Shancai and Longnü in which Guanyin plays a major role. Image Credit: Guanyin of Nanshan, statue erected in 2005 in Hainan, China. Photo taken in 2012 by Panoramio.com user GPS8.

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝗔 𝗬𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝗶𝗻 𝗙𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗵, 𝗗��𝘆 𝟳𝟬: 𝗛𝗲𝗿𝗺𝗲𝘁𝗶𝗰𝗶𝘀𝗺 "As Above, So Below" -Common paraphrasing of the 𝘌𝘮𝘦𝘳𝘢𝘭𝘥 𝘛𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦𝘵 Hermeticism is a religious/philosophical tradition from which almost all extant forms of Western Esotericism and Occultism stem, at least in part. It is named after the fusional philosopher/deity Hermes Trismegistus. 𝗘𝘀𝗼𝘁𝗲𝗿𝗶𝗰 𝗢𝗿𝗶𝗴𝗶𝗻𝘀 Esoteric tradition are broadly defined by two features: secrecy and magic. The word “esoteric” comes from the Greek word for “inner” as in “inner circle”, and typically include a doctrine of knowledge which must be kept secret and only revealed to the properly initiated. The magical aspect of these traditions, typically what we would call “the occult” is often a result simply of the veneration of knowledge; the allure and power is what you can do with it. In the West, meaning Europe, Western Asia, and North Africa (all connected by the Mediterranean Sea), Esotericism was largely spawned by a newfound multiculturalism as the Roman Empire and other states began to erode in the first century of the Common Era. Before then most Mediterranean peoples would have generally practiced some version of either or both a state religion, like the Roman Imperial cult, and an ethnic one, like the pre-Christian “pagan” religions, both more expressions of nationality and heritage than philosophy. As state powers dwindled, cultural boundaries fuzzed and fusional philosophies began to form, not tethered to any one people or state. Originally, the restricting of esoteric knowledge was likely not due to any sinister conspiracy or defense against the state, but simply the fact that they could not be easily grasped without a basic philosophical education. Hermeticism developed in this period during the collapse of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. The Ptolemies were Greeks who took control of Egypt after the collapse of Alexander the Great’s empire. Though they adopted Pharaonic aesthetics to better appeal to the Egyptian populace, the Ptolemies maintained a sharp divide between the Greek culture of the ruling class and the conquered Egyptians. In the years leading to the collapse these boundaries at last blurred and the Greek and Egyptian traditions began to mutate in earnest. Thoth, the Ibis headed Egyptian god if writing, science, and magic, fused with the Greek god of messengers and medicine, Hermes, to become Hermes Trismegistus i.e. Thrice-Great Hermes. As the tradition grew, it also incorporated many aspects of Judaism and the still-developing Christianity and Hermes Trismegistus became equated with patriarchs like Enoch or even Noah and Moses. Hermeticism generally employs three distinctive practices by which knowledge can be achieved, each one broadly attributable to one of the three major sources of the fusional system. Astrology, i.e. the observation of heavenly bodies as a means to discern the will of heavenly forces. was largely born from the Greek tradition. Alchemy, the investigation and pursuit for control over earthly transformations, stems from Egyptian metallurgy, knowledge of which was passed down through the priesthood. And Theurgy, the direct invocation of supernatural entities, stems from Judaism and other Levantine faiths. 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗣𝗲𝗿𝗲𝗻𝗻𝗶𝗮𝗹 𝗙𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗵 Part of the continued influence of Hermeticism in western culture is that it has functioned almost like a time capsule of Western magic and philosophy. After its initial popularity, the rise of European Christianity and North African Islam (both occurring around the 5th-7th centuries CE) drove many esoteric traditions, Hermeticism included, extinct or underground. Almost no original 1st century Hermetic texts remain, and we know of them primarily by means of their being referenced in contemporary sources. However Arabic versions of 3rd-8thcentury Hermetic texts made their way into Europe around the 12thcentury and were translated into Latin. These versions would become popularized in Italy at the start of the European Renaissance. During this time rediscovering ancient knowledge from antiquity was popular and romanticized, and as all the Hermetic texts claimed to be authentic dialogues from an ancient Egyptian scholar (Hermes Trismegistus himself) the audience was very receptive. Another advantage Hermeticism had among the Renaissance was its relationship to the sciences. Hermetic teachings actively promote the use of the scientific method as a means to enlightenment. This is clearest in its use of Alchemy, which in the Egyptian method used religious allegory as a means of notation. This appealed to Renaissance thinkers who built an identity on rejecting the anti-intellectual dogma of their medieval forbears. Through Hermeticism, a scientist could also be faithful. This produced the distinct nature of the Renaissance scientist, wherein the person in the room most likely to be able to produce a chemical poultice or devise a new form of irrigation was also the person most likely to believe they could commune with an angel. Isaac Newton, who was deeply influenced by Hermeticism, is a prime example of this. Interest in Hermeticism died down near the end of the 17th and early 18thcentury, but came back a century later with the popularity of Hermetic derived organizations such as the Freemasons and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, of which the famous occultists and Thelema founder Aleister Crowley was a member. Almost all modern Neo-Pagan movements have Hermetic ties, Wicca being the most direct. 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗔𝗹𝗹 𝗶𝘀 𝗶𝗻 𝗔𝗹𝗹 Hermetic beliefs are centered on the idea that there is a single true theology which was once know to mankind in a far distant age and echoes of which can be seen in all natural philosophies and religion. The use of quasi-scientific methods, like alchemy and astrology (and even theurgy if you count the mathematics used in its numerology) were core to its principles as even the laws of physics should bely this Truth. The most popularly cited Hermetic wisdom is “As above, so below”, which at its most basic level is a belief in the relation of heavenly bodies to earthly events (astrology), but expands to imply that the workings of the most grand and transcendent elements of the universe can be perceived by observing the small and mundane, and vice versa. This fusing of two things, a kind of dualistic concept of unity, is a common Hermetic idea, which can be seen in its frequent use of sacred androgyny (here being used in its most literal sense; a fusion of man and woman). The concept of a supreme god, typically called The All, is explicitly androgynous, and the original humans were as well. The division of parts, in Hermeticism, is the source of strife and ultimately illusory. Similar to South Asian religions, which may have come directly or via West Asian influence like Gnosticism, the physical world is considered to be a kind of illusion and prison in Hermetic cosmology. Our more perfect androgynous forbears had access to the secret knowledge of the universe, but for various reasons (generally some form of hubris) became trapped in physical bodies incapable of realizing the potential of our transcendent souls. Only by pursuing the true wisdom can we again become free. Image Credit: Illustration of Hermes Trismegistus from 𝘝𝘪𝘳𝘪𝘥𝘢𝘳𝘪𝘶𝘮 𝘊𝘩𝘺𝘮𝘪𝘤𝘶𝘮 (“The Alchemical Pleasure-Garden”) by Daniel Stolz von Stolzenberg, 1624

117 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝗔 𝗬𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝗶𝗻 𝗙𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗵, 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟲𝟵: 𝗦𝗵𝗲𝗻𝗻𝗼𝗻𝗴 “He evaluated the suitability of the land, [noting] whether it was dry or wet, fertile or barren, high or low. He tried the taste and flavor of the one hundred plants and the sweetness or bitterness of the streams and springs” - 𝘏𝘶𝘢𝘪𝘯𝘢𝘯𝘻𝘪, translation by John S. Major, Sarah A. Queen, Andrew Seth Meyer, and Harold D. Roth, 2010 Shennong is the Chinese god of agriculture and medicine. His name means “divine farmer”. 𝗦𝗼𝘃𝗲𝗿𝗲𝗶𝗴𝗻 𝗼𝗳 𝗠𝗮𝗻 Veneration of Shennong shows up in the historical record around China’s Warring States period, sometime in the fourth or third century BCE. He is grouped among the Three Sovereigns, a grouping of prehistoric god-kings whose rule is traditionally placed sometime in the third millennium BCE aka. prior to the first dynasty, the Xia, in traditional Chinese history. Shennong typically rules after the duo of Fuxi and Nüwa, the progenitors of all mankind, and before the Yellow Emperor, the founder of civilization and Chinese culture. He is depicted as a man with ox horns, likely as the ox is highly associated with agriculture for its use in plowing, of which both the physical tool and the technique are credited to Shennong’s teaching. In addition to plowing, Shennong is credited with teaching mankind many other agricultural tools and techniques including irrigation, food preservation, and the use of calendars. Commonly in religious traditions around the world, a deific figure like Shennong’s knowledge of these things would be innate, an aspect of his divinity, but this is not so with Shennong. Shennong explicitly knows and is able to teach mankind because he experiments and learns. This is very apparent in his other area of expertise: medicine. Like with agriculture, Shennong is credited with creating many aspects of Chinese traditional medicine; knowledge of medicinal herbs and poisons, acupuncture, measuring a pulse, and even tea when he drank water that his herbs had fallen into. He knew all this because he tested it all first on himself. In addition to his horns, Shennong’s other most distinctive portrayal is that he is sampling herbs, an act that would eventually result in his death by poisoning. 𝗢𝘅 𝗛𝗲𝗮𝗱𝘀 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗙𝗹𝗮𝗺𝗲 𝗞𝗶𝗻𝗴𝘀 Shennong is not the only Chinese figure to be depicted as ox-horned or ox-headed. Most notably is Chiyou. Chiyou, from the Han Chinese perspective, is a prehistoric villain, the warchief of the Nine Li Tribe which the Yellow Emperor ultimately conquers. However, to many of the Hmong/Miao people of southern China he is a culture hero and founder of their people and culture, filling a similar role to Shennong. Its likely the two figure share, at least in part, some historical origin and their commonalities led some ancient scholars to link the two by lineage. Another common figure, both in the tales of Shennong and Chiyou, is the Flame Emperor, or Yandi. The flame emperor is a contemporary to the Yellow Emperor and significantly the only other person to hold the title of emperor (“di”) at that period. The Flame Emperor rivaled the Yellow Emperor until going to war with the Nine Li tribe of Chiyou. After suffering defeat the Flame Emperor submits to his formal rival in order to defeat Chiyou. Together the Yellow and Flame Emperors best Chiyou and establish the start of Chinese culture (the term “Descendants of the Flame and Yellow Emperor” is still used to describe Chinese people, especially Han Chinese). Where does Shennong fall into this? He is, of course, the Flame Emperor himself. Shennong has long been associated with fire, a tool in slash and burn agriculture as well as the catalyst for making tea and medicines. This also places him in opposition to the Yellow Emperor as a rule of southern China, a role also filled by the similar Chiyou, further implying a common historical origin for the two ox-headed deities. That said, later historians would imagine the title of Flame Emperor as a hereditary one, with Shennong starting the line but ultimately the one who would capitulate to the Yellow Emperor being a descendant. This preserved the idea of Shennong as a pre-Yellow Emperor sovereign, and also avoided putting the two ancestral figures in direct conflict. Image Credit: Illustration from 𝘖𝘶𝘵𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘊𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘴𝘦 𝘏𝘪𝘴𝘵𝘰𝘳𝘺 by Li Ung Bing, 1914

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝗔 𝗬𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝗶𝗻 𝗙𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗵, 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟲𝟴: 𝗩𝗶𝘀𝗵𝗻𝘂

“O ye who wish to gain realization of the Supreme Truth, utter the name of "Vishnu" at least once in the steadfast faith that it will lead you to such realization.” -Foreword by N. Raghunathan to P. Sankaranarayanan’s translation of 𝘚𝘳𝘪 𝘝𝘪𝘴𝘯𝘶𝘴𝘢𝘩𝘢𝘴𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘢𝘮𝘢 𝘚𝘵𝘰𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘮. The quote claims to be from the 𝘙𝘪𝘨 𝘝𝘦𝘥𝘢, possibly hymn 156 of the first book, though if it is, it is not from any standard English translation.

Vishnu is the Hindu god of preservation and is considered to be the supreme deity in Vaishnavism, Hinduisms largest branch. In addition to his supreme status, he is best known in relation to his avatars, which include central figures in the epics 𝘙𝘢𝘮𝘢𝘺𝘢𝘯𝘢 and 𝘔𝘢𝘩𝘢𝘣𝘩𝘢𝘳𝘢𝘵𝘢. The traditional etymology for his name is “all-pervasive”.

𝗔𝗹𝗹-𝗣𝗲𝗿𝘃𝗮𝘀𝗶𝘃𝗲

The name Vishnu is traceable back to the oldest of Hindu scripture and some of the oldest texts in any Indo-European language: the 𝘝𝘦𝘥𝘢𝘴, which date back to around 1500 BCE. In these texts Vishnu is less prominent than figures like Indra (king of the gods) or Agni (god of fire) and Vishnu is portrayed as a god of the heavens, associated with the sky, light, and the sun. His rise to supreme deity likely occurred as a result of the aggressive fusion of several other deities between the 7th and 4thcenturies BCE. Prominent among these were deified tribal folk heroes like Vasudeva and Krishna (still popular in his own right and as an avatar of Vishnu). Both of these figures and others like them were popular and relatable deities who did not come from the Vedic tradition i.e. from various folk traditions as opposed to (at the time) Hindu orthodoxy. An attempt to consolidate these popular beliefs with the already orthodox Vedic establishment brought figures like Narayana, a supreme fusional deity, and Vishnu, the embodiment of heaven, into the fold as well. This development establishes Vishnu’s transcendent supremacy, pluriform nature, and widespread appeal. By the writing of the Hindu epics (roughly 3rd or 4th century BCE) Vaishnavism was well established and able to appeal to Hindu’s of all denominations. In this way Vishnu quite literally lives up to his name, poised to cross the exceptional diversity of Indian religious traditions. Vishnu’s pervasiveness is also relevant to his own, contemporary doctrine. Vaishnavism is a heavily ‘Advaitic’, a descriptive term in Hindu philosophy which literally means “non-dualistic”. What this means is that all of existence is, ultimately, singular and all distinctions between things are illusory. To massively simplify: reality is an illusion and Vishnu represents the singular whole of all things into one. Thus Vishnu is, again, truly all-pervasive.

𝗦𝘆𝗺𝗯𝗼𝗹𝗶𝘀𝗺 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗔𝘃𝗮𝘁𝗮𝗿𝘀

Possibly due to his fusional past, Vishnu is the god most associated with avatars i.e. a mortal incarnation of the deity born into the world in order to fulfill a task of cosmic importance. Though Vishnu is not the only Hindu deity to have avatars, his are core to his worship. There are many figures ascribed to Vishnu’s avatars, but most important is the doctrine of ten avatars aka. The Dashavatara. This cycle tracks Vishnu’s involvement in earthly affairs from the origin of mankind to the future end of days. As this series has already featured an entry devoted to avatars, including the Dashavatara, I will simply link that HERE. Vishnu is often contrasted, or complementary to, a fellow member of the Hindu trinity and supreme god of Hindu’s second largest branch: Shiva, god of destruction (perhaps better rendered as “transformation” to a Western audience). While Shiva actively dances the universe into being, Vishnu dreams it into existence. Shiva is an ascetic, dressed in a tiger’s skin with matted hair, while Vishnu is regal in his fine robes and jewelry. Shaivism (worship of Shiva as the supreme deity) is most common in Dravidian speaking south India, Vaishnavism in Indic speaking north India. Vishnu is most commonly depicted in a four armed form, carrying his four relics: The Chakra called Sudarshana a weapon which has also been deified in its own right, the mace Kaumodaki, representing Vishnu’s age and strength, the conch shell Panchajanya, which Krishna blew to usher in the climactic war of the 𝘔𝘢𝘩𝘢𝘣𝘩𝘢𝘳𝘢𝘵𝘢, and the lotus, the Hindu symbol of transcendence and purity. His mount is the legendary bird Garuda and his bed is the king of Nagas (mythic and/or literal snakes). The devotion of both birds and snakes, warring entities in Hindu cosmology, is a further representation of Vishnu’s all-pervasive, Advaitic nature. In addition to his four armed form, another common depiction is the Vishvarupa, literally the “universal form”. This form often has many faces extending to the left and right and many arms forming a wing-like outline, though the arrangement of heads and arms may vary and sometimes it is simply the form of Vishnu with all of the Hindu universe mapped out upon him. This was the form that famously appears in the 𝘔𝘢𝘩𝘢𝘣𝘩𝘢𝘳𝘢𝘵𝘢, when Krishna reveals to Arjuna that he is an avatar of Vishnu and shows him his true all-pervasive form. Arjuna’s mortal mind cannot process the vision, though is not destroyed by it as is depicted for similar events involving Zeus in Greek mythology, and ultimately the encounter gives Arjuna the clarity of purpose he needs to commit to the righteous war of the 𝘔𝘢𝘩𝘢𝘣𝘩𝘢𝘳𝘢𝘵𝘢. The symbolism of this form is clear: all people, things, and even other gods, all things good and bad, great and small, are part of Vishnu.

Image Credit: From a translation of 𝘔𝘢𝘩𝘢𝘣𝘩𝘢𝘳𝘢𝘵𝘢 by Ramanarayanadatta astri, 1901

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Return to Faith

Hello, I began this project January of 2020, and maintained it for about 3 months. At that time a global pandemic set in, uprooting life in many ways. This compounded with me purchasing a house and moving in to said house with my brother and boyfriend, and all told meant that this needed to take a backseat. Now, in 2021, I hope to complete the series. I am simply going to begin where I left off and number the day appropriately, starting with 68. I hope you all will continue to enjoy. Thanks, -Jack

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝗔 𝗬𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝗶𝗻 𝗙𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗵, 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟲𝟳: 𝗕𝗼𝗼𝗸 𝗼𝗳 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗗𝗲𝗮𝗱

“O you gates, you who keep the gates because of Osiris, O you who guard them and who report the affairs of the Two Lands to Osiris every day; I know you and I know your names.” -𝘉𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘋𝘦𝘢𝘥, spell 144, as translated in 𝘈𝘯𝘤𝘪𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘌𝘨𝘺𝘱𝘵𝘪𝘢𝘯 𝘉𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘋𝘦𝘢𝘥: 𝘑𝘰𝘶𝘳𝘯𝘦𝘺 𝘵𝘩𝘳𝘰𝘶𝘨𝘩 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘢𝘧𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘭𝘪𝘧𝘦, 2010

The 𝘉𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘋𝘦𝘢𝘥 is a class of Ancient Egyptian funerary texts which contained a combination of information and magic spells to aid the deceased in the afterlife. The title “Book of the Dead” is a description coined by one of the fathers of modern Egyptology, Karl Richard Lepsius who was the first modern European to translate the text. The Egyptian name (written without vowels) is “rw nw prt m hrw” which means something like “the book of coming forth by day”.

𝗗𝗲𝘃𝗲𝗹𝗼𝗽𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗥𝗲𝗱𝗶𝘀𝗰𝗼𝘃𝗲𝗿𝘆

The 𝘉𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘋𝘦𝘢𝘥 developed out of other funerary texts, the Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts. The Pyramid Texts are the oldest known religious texts from Ancient Egypt, dating to around the 24th century BCE, and were carved into the walls of tombs, specifically only the tombs of pharaohs. Around the 21st century BCE the Coffin Texts were developed. These are similar in content to the Pyramid Texts, though were typically inscribed on or on the inside of sarcophagi, hence the name. This also represented a significant broadening of the funerary text tradition, extending beyond the pharaoh to any Egyptian wealthy enough to afford it. Considering these texts were a crucial aspect of existence in the afterlife, this was a kind of religious revolution. The publicizing of the afterlife continued to broaden with the 𝘉𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘋𝘦𝘢𝘥, developed in the 18th century BCE. These texts were typically written on more widely available papyrus and linens used to wrap the dead and were well illustrated. Originally, each instance of a 𝘉𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘋𝘦𝘢𝘥 was completely unique, and though they were always customized they developed a standardized internal structure in the 8th-7th century BCE. The tradition finally died out in the 1st century CE. Africans, Asians, and Europeans would all rediscover these texts as early as late antiquity, but by then knowledge of hieroglyphics was lost. The French invasion of Egypt under Napoleon at the end of the 18th century led to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, a stele containing a 2nd century BCE decree. At the time of its creation, Egypt was under Greek rule, and thus the decree was written in both Egyptian and Ancient Greek, knowledge of which had never been lost. Using the Greek as a guide, the linguist Jean-François Champollion developed the foundation of Hieroglyphic translation in 1822. Champollion tragically died young ten years later, aged 41, just as the fruits of his research were ripening. Among the first things effectively translated was the 𝘉𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘋𝘦𝘢𝘥 in 1842. As mentioned, knowledge of these texts had long persisted even in Europe. As they were found in tombs and bore artwork of gods, people already believed they were important, but could only guess at their function. Before translation, they were generally thought to be an Ancient Egyptian religion version of the Bible.

𝗛𝗮𝗻𝗱𝗯𝗼𝗼𝗸 𝗳𝗼𝗿 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗥𝗲𝗰𝗲𝗻𝘁𝗹𝘆 𝗗𝗲𝗰𝗲𝗮𝘀𝗲𝗱

The actual function of the 𝘉𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘋𝘦𝘢𝘥, and its predecessor Pyramid and Coffin Texts, was not to educate and enculturate the living, as a Bible or Quran might. Instead they were solely for use by the dead. Ancient Egyptian Religion had a strong and developed vision of the afterlife. So developed in fact, that they felt it basically impossible to navigate without help. The book contained magic spells that would aid the deceased navigate and overcome obstacles they would encounter, as well as knowledge of the gods and monsters they would encounter. No single 𝘉𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘋𝘦𝘢𝘥 contains all the spells now attributed to them (almost 200). If the deceased had the forethought to have done so, they could request the inclusion of certain items, or their family could do it posthumously. Different scribes learned differently, and of course the tradition was always developing over the centuries. Often, they could even be prefabricated, with blanks left for the scribe to fill in the name of the eventual owner. Inclusion of the name was important, and appeared many times in the texts. This was another way in which the texts served; helping the deceased to remember their living name which the Egyptians considered to be a vital aspect of one’s soul. After the books became somewhat standardized, their internal structure went like this: the first quarter contained methods by which the deceased could restore its body and maintain it as well as guides on descending into the underworld. The second quarter contained detailed descriptions of gods, monsters, and supernatural places that the deceased would need to be able to reference later on. The third quarter describes how to embark and ride upon the sun ark, which travels across the sky each day before reaching the underworld and judgement. This section contains the infamous “weighing of the heart”, in which the deceased’s heart was weighed against a feather which represented Maat, the Egyptian force of truth and order. Before this though, the deceased would need to declare themselves free of sin, a process that involved addressing each of the 42 underworld judges by name, so one can start to see why a detailed guidebook would be necessary. The final section tells of assuming one's role amongst the gods, as well as descriptions of many protective amulets.

Image Credit: 𝘚𝘱𝘦𝘭𝘭 𝘍𝘰𝘳 𝘕𝘰𝘵 𝘓𝘦𝘵𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘈𝘯𝘪'𝘴 𝘏𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘵 𝘊𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘵𝘦 𝘖𝘱𝘱𝘰𝘴𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘈𝘨𝘢𝘪𝘯𝘴𝘵 𝘏𝘪𝘮, 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘎𝘰𝘥𝘴' 𝘋𝘰𝘮𝘢𝘪𝘯, from 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘗𝘢𝘱𝘺𝘳𝘶𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘈𝘯𝘪, spell 30B, c. 1250 BCE

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

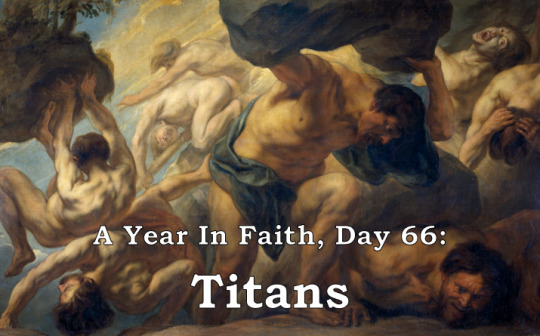

𝗔 𝗬𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝗶𝗻 𝗙𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗵, 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟲𝟲: 𝗧𝗶𝘁𝗮𝗻𝘀

The Titans are a group of gods in Ancient Greek mythology who represent a generation of gods prior to the gods which are actively worshiped. The origin of the word “Titan” is unknown, though the 8th century BCE writer Hesiod provides folk etymologies the it means something like “to strain” or “vengeance”, reflecting their role as adversaries. It may also come from an Anatolian or Levantine language.

𝗧𝗶𝘁𝗮𝗻𝘀 𝗶𝗻 𝗔𝗰𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻