Text

Was anyone going to tell me that there was an art exhibit based on the gay love letters exchanged between Johannes von Müller and the fake count who defrauded him, or was I just supposed to figure that out for myself (source):

"Marc Bauer: I Emperor Me

The title of Marc Bauer’s latest series of drawings is taken from a tradename for an industrial glove, the EMPEROR ME108 Heavyweight, produced by Marigold Industrial. The inspiration for the drawings, by contrast, is rather more sentimental: the twohundred-year-old amorous correspondence, written in French and only recently published, between Johannes von Müller, custodian of the Imperial Library of Vienna, and a younger man of his acquaintance posing in the letters as a ‘Hungarian count’, with the plausibly unpronounceable name of Louis Batthyány Szent-Iványi. What do these startling opposites—the ‘Emperor of hand protection for industrial use’ and a historical case of aristocratic fraud at the dawn of the Austrian Empire—have in common? One would think very little. But in Marc Bauer’s hands they represent power, absence, and the objectification of love and desire.

The drawings feature fetishized articles of clothing: a latex glove, a leather Chap, a shirt. These objects are isolated and alienated from their original function. They are even, one could say, alienated from their secondary function as fetish-wear. (For seen without a human leg, it is initially hard to recognize the Chap for what it is.) It is very unlikely that the glove, the ‘emperor’ of the series, has ever been put to ‘industrial use’. The manufacturers state its possible applications as being in ‘the chemical industries, fishing, agriculture, mining’. But this is an art gallery, not a pig-shed, and the majority of present viewers are probably more familiar with its ulterior use in the practice—or rather, at least, the dark signification of the practice—of fisting. In this regard, Bauer’s choice of subject might be called camp. He invites us to understand these objects through a shared, ironizing code. He suggests sex, or at least, a certain type of sex. But there is nothing camp about these images. There is nothing camp about their rendering—which is anything but playful—nor their meaning, which is about the signification of love in general, not just in secret between a certain type of men.

The gloves, the sleeves, the strangely rigid leg-covering should be inanimate objects. But somehow they are not. Larger-than-life and viewed from the same perspective, they seem to resonate with the memory of their wearer. They are more than clothing. They are like the dead skin shed by their wearers, the remnants of… affection? desire? submission? One is almost tempted to read a narrative into them, as markers that symbolize different stages in a relationship or affair. In this they are similar to the quotes from the letters transcribed in the portfolio. The artist has taken each quote from a different letter. Each quote captures a different point in the unusual story of love and betrayal in early 19thcentury Vienna. They plot a descent from sentimental (frankly naïve) ardour, to betrayal, then melancholy and shame. The letters are fragments of desire, just as the objects in the drawings are. Marc Bauer seems to suggest that we can only desire or love a person in fragments, that we can only ever grasp a person in fragments, in snippets of sentiment, and that for desire or love to exist it must persist in the person’s absence, through objects they have touched. From these fragments of longing—letters, slowly dying flowers, a crushed shirt—one construes a love affair; in the drawings it is a modern one, in the letters it is historical.

The correspondence traces a love story between an esteemed Swiss-born scholar (Müller) and a Swiss-born swindler (Hartenberg), posing as a count. Müller’s infatuation was entirely lived out in his imagination. He never met the ‘count’. It was love experienced as the acute presence of another’s absence, just as the glove’s form is very literally a presence in absence. The ‘count’s’ letters were written to instil desire not just through their words, but through the very paper on which they were written. For in 1802, when the correspondence began, letters were, we can safely assume, one of the most commonly fetishized objects. A letter sometimes bore the loved one’s scent and always bore the loved one’s touch, the imprint of a hand, the perspiration of the writer’s fingers. Before typewriters, stenography, and email, letters were objects that signified, among other things, the absence of the writer combined with the presence of the reader in his or her mind. Letters were always written by hand and read while held in the hand. The glove, obviously, is also all about the hand, and the sleeve ends in a hand. The artist repeatedly emphasises the hand, objectifies it, because he wants to evoke the sense of touch and contrast this with the absence of the loved one’s touch that lingers only on these lifeless things and, through them, in the mind.

The ribbons, another ironic, historicizing gesture, are also there to tempt our sense of touch and remind us that in a drawing, unlike in a sculpture or painting, if we reach out and touch, there is nothing to feel but paper. But in his rendering of the glove and the sleeve, Bauer also draws attention to his own hand. For these are drawings. They are the graphic legacy of the movements of a hand. Bauer even references the ‘graphic legacy’ of the art of drawing—by drawing, with clear affection, the folds of the sleeve, in memory of the wearer, perhaps, but also in (unconscious?) memory of the motif of drapery in the graphic arts, the fondness—no, the obsession—of artists as long ago as Schongauer and Dürer to draw folds as a way to show off their skill and freeze time in the prolonged moment of their gaze. For elaborate folds only occur through movement, but, like the bouquet of flowers—a still life—they can only be truly seen when the subject stands unnaturally still, ‘plays dead’ as it were, so that he or she and the clothes he or she is wearing can live on in a work of art—just as a fictitious love affair, once exposed, once dead, only lives on in letters."

#aggiecore: vibes#you can best believe that if aggie had ever received any letters from Phillip during the war#he'd be huffing those things til his undying day#8|

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Preorder Deadline Reminder: 【Knight's Star-Moon Sword】 Gothic Lolita Ouji Lolita Jacket and Trousers

◆ Don't Miss Them >>> https://lolitawardrobe.com/knights-star-moon-sword-gothic-lolita-ouji-lolita-jacket-and-trousers_p8475.html

◆ The Preorder Will Be Closed After December 10th!!!

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Rahul Mishra Spring 2024 Haute Couture

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

48K notes

·

View notes

Text

Rising from the dead to show this beautiful sculpture of Pan and Apollo 🌱☀️

93 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kirsten Valentine, Untitled (Love Handle), 2019

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

me admiring a beautiful man: wow he sure does have a vulnerable looking throat, huh?

34K notes

·

View notes

Text

Thesis: the rise of fanwank and anti culture correlates directly with diminished understanding of what “romantic”, in a literary sense, actually means.

It doesn’t mean “this is ideal or healthy or even realistic”. It means “this is beautiful, this is tragic, this is grotesque, this stirs emotion”, even if it’s not, as @starryroom puts it, something you would be comfortable seeing play out in front of you at Taco Bell. It’s about grandiosity and mythology and heroism writ large. It’s about playing with the id, as beautiful and terrible as it can be.

91K notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint Sebastian (c.1615) | Guido Reni

263 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eton, Year 1

Rating: T Archive Warnings: No Archive Warnings Apply Category: M/M, Gen Word Count: 4,351 Warnings: Non-sexual grooming of a minor*, Blood, Child Neglect, Implied/Referenced Child Abuse *The "non-sexual grooming" warning relates to an inappropriate relationship established between an adult and a 13-year old boy. There is no overt sexual content, and the characters are not intending to engage in either a sexual or romantic relationship from either side. However, the scene in question is purposefully written to evoke such a relationship by use of language and imagery, and it may make readers uncomfortable. Read at your own risk.

***

When Azriel Edgemont arrives at Eton, it is with the same amount of pomp and circumstance with which he is treated every day of his life; which is to say, none whatsoever. His arrival goes unremarked upon by any except the headmaster there to welcome him to the school. His governess gives him a tight smile; the driver pulls down the valise from where it’s settled on the back of the car; and he is left choking on gravel and dust as the vehicle pulls away. He is not surprised not to get a hug goodbye, but it’s disappointing all the same.

This piece was written to try to solidfy some details about Aggie's entry into Eton, how he found music/DeVry, what music and his relationship with DeVry ended up meaning to him, and a little more about Alastair and he's early relationship!

Read on ArchiveofourOwn, or proceed below the cut:

When Azriel Edgemont arrives at Eton, it is with the same amount of pomp and circumstance with which he is treated every day of his life; which is to say, none whatsoever. His arrival goes unremarked upon by any except the headmaster there to welcome him to the school. His governness gives him a tight smile; the driver pulls down the valise from where it’s settled on the back of the car; and he is left choking on gravel and dust as the vehicle pulls away. He is not surprised not to get a hug goodbye, but it’s disappointing all the same.

When the headmaster holds out a hand, it takes a moment of effort for him to stop himself from reaching for it with the upturned palm of a young boy seeking guidance. Instead, he meets the dry, papery palm with his own, doing his best to emulate a friendly shake like he has seen Father give. By the expression on the headmaster’s face, this is not entirely successful.

“Welcome to Eton, Edgemont. We’re very pleased to have you here with us,” the headmaster lies.

* * *

It soon becomes very clear that Azriel is different from the other boys at Eton. He’s not the smallest, but it’s a close thing among the boys of his year. He gets cold easily in the drafty hallways of the ancient building; even on the warmest days, he goes about in his cardigan, sleeves pulled down over his fingers to combat the chill wrought by his feeble circulation.

Because Azriel is lacking, a little, in the socialization department—being raised essentially in isolation by emotionally unavailable nannies and governesses and all but ignored by your parents will do that to you—and because he stands out among his peers, he gets into trouble a lot. He’s pushy, loud, and clearly craves attention however he can get it—even if that attention is negative. He is unliked, and he isn’t allowed to forget it, and so he determines to dislike everyone else first.

In an attempt to try to tame him, the faculty shunt him about from extra-curricular to extra-curricular. It’s clear fairly early on that sports are a no go—he breaks his arm the first day on the rugby field—and his attempt at running track is laughable. (He complains the entire time; he’s hot, he’s sweaty, he’s tired, the track uniform is tacky and unflattering. He runs like a limp noodle.) He lacks the patience or manners for chess club. He’s loud and emotionally hyperactive; they try him on the debate team, thinking that his penchant for arguing and reluctance to ever leave anything well enough alone will serve them well, but he just insists on making ad hominem arguments that basically amount to innuendos at the other boys until they’re too angry and/or flustered to come up with cogent responses.

There is one good thing that comes out of debate club, for Azriel at least. In the stuffy room on the third floor where they meet four times a week, he is first introduced to Alastair Mercotte. Alastair is a year ahead of Azriel; the debate club spans all ages, with the older taking on a mentorship role for the younger, and it’s no different with the two of them. Alastair is an intelligent boy, well-liked by the faculty; he has an impressive span of extracurriculars, and there is every expectation that he’ll make Head Boy in a few years. (Is this a thing? Idk) He spends most of his free time reading, and writing—sometimes poetry, sometimes fiction, sometimes treatises or analyses of the things he’s read recently. He’s always first with his hand up in class, first to hand in his papers, but he uses his goodwill with the faculty to secure things for the other boys—taking their books out to the lawn to read on a particularly nice day, arranging for a few extra minutes off between classes in exchange for good behaviour. As a result, while there is still some teasing amongst his classmates for being a studious teacher’s pet, it’s usually affectionate; as though he is a mascot, or a good luck charm, able to talk teachers and House Masters out of punishments and into treats and rewards.

He and Azriel do not strike up a quick friendship. Azriel treats him much like any of the other boys in the debate club; Alastair’s hair, penchant for poetry, and tendency to use flowery language when making his arguments are all excellent targets for Azriel’s off-topic character assassinations. (Neither of the boys knows this, at first; but it is a shield in every sense of the word, like pulling pigtails if such an activity were, in fact, an irrefutable reality of crush-hood and not an overlooked and brushed aside early entry into misogyny and the violation of physical boundaries and consent.) Azriel sees, and wants, and doesn’t know how much or what he wants; like an infant without words, he kicks up a fuss instead of knowing what to do with the wanting. For Alastair’s part, underneath the younger boy’s bluster and attitude, he catches glimpses of a brilliant intelligence; cleverness, and wit, were he afforded the chance to put it to use instead of reducing it to a crude double-edged sword with which to protect himself.

Azriel lasts longer in debate than any of the other extra-curriculars he has been tested in so far, and much of that is due to Alastair’s influence; but it still is short-lived. Azriel is withdrawn from debate before Alastair and he can actually strike up any kind of a friendship. Alastair has a private argument with the teacher in charge of the debate team about this; the teacher finds Azriel and his refusal to engage with the art of debate in good faith disruptive to the other students, whereas Alastair tries to make the argument that he has been improving, if he could just be given more time. In the end, though, Alastair is still just a 14-year-old boy, and his opinions are firmly, if gently, shut down.

Instead, he resolves to seek out Azriel for himself. At lunch, or on the quad in the evenings, he finds excuses to occupy Azriel’s space; to ask him questions, draw him into conversation, sometimes even debate. For Azriel’s part, it takes time to trust that Alastair’s attention isn’t just another cruel ploy like so many that the other boys have engaged him in. He stays prickly and standoffish as long as he can, but Alastair’s refusal to be dissuaded starts to thaw his center—especially once he realizes that Alastair seems to prefer his company to the other boys of his year. The two begin to spend more time together; Alastair’s company doesn’t completely shut down the bullying of the other younger boys, and has no effect at all on what he endures at the hands of the upperclassmen, but his torment does abate somewhat, and Alastair proves capable of defusing his most mercurial moods.

This development takes time, however; and while Alastair is slowly breaking down Azriel’s barriers in quiet moments in the library, the mess hall, or out on the lawn, the faculty is still trying to find a way to handle the willful Edgemont boy. And so, 7 months into the school year, Azriel walks into the music room for the first time.

* * *

John DeVry is a music teacher and choirmaster for the young boys’ choir at Eton. He is known for his exacting standards; an ear capable of hearing the smallest deviations in pitch, and identifying exactly which chorister is out of tune. He isn’t full time faculty, apparently spending his days and some of his evenings bent over ancient paintings, rubbing at them with cotton swabs and turpentine, but a few nights each week, he descends on Eton to lead the boys’ choir through vocal exercises, music theory, and rehearsal of hymns and madrigals alike.

He is something of an eccentric, to both the boys and faculty; but there is something severe about his gaze and the way his French tongue clips his English words that keeps them in line. Rumours persist among the boys that the cane he uses as he walks serves another purpose; that he is a great lover of corporal punishment, and has a wicked strike, despite appearing more an academic than an athlete. They still make fun of him, of course, as is the wont of young boys with figures of authority, but never where he can see or hear. All but the bravest wait until he is entirely off campus before pulling their faces, or mimicking his heavy accent. In class, though, and in practice, they are dutiful and attentive.

DeVry’s ability to elicit this behavior in the boys is what is top of mind when Azriel is placed into the choir. The faculty neither know, nor care, about whether or not he is musically inclined; just anything to invest some small amount of discipline in the boy, or at the very least, to get him out of their hair. What is unexpected, however, is the degree to which Azriel takes to music, and to his teacher. It’s a tough go, at first; Azriel is resistant to the instruction, gives his usual attitude in response to DeVry’s authority and keeps his mouth determinedly shut. But rather than butt heads with the child—making him dig his heels in further—DeVry gives him a challenge, one day, as the boys are filing out of the room.

“With this attitude—you swan in here, strutting like a peacock. Clearly, you think you are something special, no, master Edgemont? Perhaps—you could prove it.”

It’s this acknowledgement—this allowance, that perhaps Azriel is special and important, rather than any possibility of such being shut down immediately—that gets through to him. That, combined with the early conversations he has with Alastair, where the other boy tells him similar things, praises him for his cleverness and his wit and charms, is what prompts him to give singing a reluctant go. They are the only two left in the music room; there is no audience, no one to tease or ridicule, and DeVry is standing by the piano, looking intently at Azriel. It’s the first time, really, since coming to Eton that he has had the attention of a teacher that is not related to admonishment or punishment; the first time, too, that he’s been spoken to as though capable of rational thought, rather than lectured or spoken down to. And so—he nods.

DeVry tilts up the cover of the keyboard, laying his hand on the ivory keys, and plays through a simple scale. He prompts Azriel to try to match the notes; Azriel doesn’t know how. They spend a while on one note, one key, played over and over until he can get the feel for it; then they run the scale again. It’s clear the register is too low; DeVry moves up an octave, first, then a third, then a scant semitone, Azriel doing his best to replicate the string of notes each time. It’s there—DeVry tells him its G5, whatever that means—that something just clicks . It’s like the sound, the notes, reverberate inside of his skull, hitting a resonance that feels right. He can’t help it; there’s a smile on his face, and he is gratified to see the faint traces of one playing around the edges of DeVry’s stern mouth.

He sings through the scale once more before DeVry interrupts him, stepping forward to lay a hand on Aggie’s stomach--”Your diaphragme is here, Azriel; imagine this muscle, here, it is pushing up the air from your lungs.” He tries again, and is delighted by the approving nod the teacher gives him. DeVry steps into his space again, this time laying his fingers to either side of Azriel’s jaw. “Hinge from here; keep this open.” His mouth drops open obediently. “Good. Now, the tongue—to the bottom of your mouth. Imagine— une prune , a plum, roasted and hot, sitting at the back of your throat—yes, like that.” It continues like this, DeVry making small adjustments to Azriel’s technique, giving him instruction—how to stand, how to breathe, how to hold his arms. He keeps changing the notes and pitches on the piano, having Azriel sing them back to him and listening intently to the vocal quality and timbre that he hears. Azriel’s eyes track DeVry throughout, his own wide and shining at the care and attention being paid to him in this moment.

“Oh, my dear boy,” DeVry murmurs, after he is satisfied, having determined the upper and lower limits of Azriel’s untrained vocal range. His eyes appear almost misty, faraway. “You are something very special, indeed.”

Azriel doesn’t know how much time has passed in the music room, under DeVry’s undivided attention. His stomach suddenly growls; DeVry looks at him sympathetically. “I apologize—I have made you miss your dinner. I hope you will forgive me, my boy; you have a rare gift, and I seem to have lost myself.”

Azriel is mistrustful of this praise, at first. He thinks about the music he would sometimes hear at home—the singers sounding hollow, their voices either pitched high and warbling, or lower, smoother. To him, his voice sounds like neither of those. But then, the music the choir has been rehearsing is nothing like the jazz his parents would play during their parties with their friends, either. “Is that just something you’re saying? To get me to behave myself? Don’t think I don’t know how the teachers all talk about me.” DeVry looks down at him, and rests a hand high on Aggie’s shoulder, at the base of his neck. “You are exceptional, Azriel. You could very well be the greatest singer of your generation, with the proper tutelage. I would like to tutor you, train you in private lessons. I will arrange with your other teachers for us to have time to work on developing this remarkable talent of yours. But, for now—let us see what we can find for you to eat, my little songbird.”

* * *

This attention—devoted, single-minded—from DeVry seems to be the missing key in Azriel’s school life. With his music and vocal lessons as an outlet, and his companionship with both the Frenchman and his new friend Alastair, Azriel’s outbursts and desperate attention seeking are significantly calmed. He makes of himself less of a target, and so he is targeted less frequently. Azriel finds that he doesn’t want it to end, and so he pours himself into his lessons; when DeVry expresses dissatisfaction with his grades in his regular classes, he focuses there, too, afraid of failing, afraid that this attention will be snatched away from him without warning. His dedication is rewarded. He enjoys special treatment from the teacher. At least once a week, he is taken out of mess hall in the evening to have dinner at a restaurant with DeVry, and from there, chauffeured to theatres and operas and concert halls for thrilling musical performances.

Azriel learns, very early on, that DeVry also shares his distaste for jazz music. For Azriel, jazz was the thing his parents loved more than their son. It represented all the various and sundry things, in fact, that they loved more than their son. Parties, substances that alter the mind and emotions, late nights and early mornings with raucous laughter ringing from down the hall while a lonely boy shoved his head under the pillow trying to sleep. Jazz accompanied the smell of smoke, the acrid tang of alcohol. It sounds like shushing, scurrying, dismissal; it is the soundtrack that accompanies the refrain, “Goodnight darling, we love you, we’ll see you tomorrow night,” spoken muffled from out in the hall to strangers whose faces Azriel doesn’t know by the strangers that he should, words that he himself has never heard.

DeVry’s dislike is, obviously, seated in something very different; he says that he finds it obscene, the ways it breaks the rules of music, key and meter changes where none should be, time signatures that are barely suggestions. The instruments are loud and brassy, the singers have no talent to speak of; his complaints are plentiful. Azriel feels a thrill of validation in this; that his opinion should be shared by a man like DeVry, cultured and learned and intelligent. He admits to Alastair one evening over dinner in the mess hall that he hadn’t realized how many different sorts of music there were—he knew jazz, and the old hymns that his caregivers would hum to themselves in moments of idleness—but the breadth of the musical experience gives him a sense of wonderment. “I never knew how much there was, all the different kinds? Beethoven and Schubert and Chopin—they’re all so lovely, and I can’t believe I didn’t ever hear them before!”

“But—what about Ode to Joy? You must know Ode to Joy.”

“Of course I know Ode to Joy, that’s Beethoven, but that’s—there’s more than that, too. Better. Monsieur DeVry says he will take me to see the London Opera next month, when they perform the Carmina Burana— it just debuted in Frankfurt last year!”

And that’s the thing, for Azriel. He gets the attention of an adult authority figure, something he has been deeply and wordlessly missing for most of his life. He earns the respect and praise that he craves, for his beautiful singing voice, his natural talent, and for working hard to improve in order to keep his patron’s attention. But DeVry’s tutelage also unlocks for him a new and true passion for music. He finds something deeply personal, freeing, in his musical exploration. When DeVry takes him to a performance, he finds himself moved by the emotions and expressions that can be communicated by soaring melodies in languages he doesn’t understand. The soprano stands in the spotlight, and he can feel her heartbreak and anguish. The baritone, an imposing presence, strides across the stage belting out his fury, and Azriel knows—without even reading the program—that his anger is based in injustice and infidelity. Even the artistry of the orchestra—DeVry teaches him to identify all of the instruments by sight, and by sound—they craft a tapestry of music that tangles up with his emotions, leaving him in tears by the end of it more often than not.

When DeVry asks, “Azriel, whatever has affected you so?” It’s all he can do to give a helpless shrug.

“It’s just—it’s all so beautiful. It’s not sad, or happy, or anything, it’s just—it’s beautiful . It feels like something holy.” He turns his gaze on his mentor, face twisted up as though worried about disappointing him—DeVry is not a religious man, he has learned, despite the choir’s typical repertoire—but DeVry’s expression is kind, and satisfied.

“Yes, it does, doesn’t it.”

Azriel comes back from these performances and pours what he has learned into his own music. He still feels everything, so much, so deeply; want, and anger, loneliness and despair and a deep, quivering need to exist , to be perceived. In a way, music is an outlet. Singing is a release. He can pour his emotions into it. He can fill the low notes with his dreads and fears, the boiling impotent rage he still sometimes feels when he considers the lonely, empty void of his childhood. The notes at the top of his register, as he pitches into a bright falsettonne, feel like screaming—in grief, in anger, in that wordless helpless infantile squalling of the babe who wants and does not know what to do with the wanting. But no matter what—no matter the notes, or the emotion he inflects them with—it’s beautiful. From this, he learns; There is nothing about me that is not beautiful .

* * *

Their conversation--the power of an art form to inspire emotion—seems in turn to inspire something in DeVry. He sees Azriel’s love and appreciation for the art of music, for the pure and simple beauty of being moved by melodies and harmonies and the single tremulous note of a flute, and takes it upon himself to expand Azriel’s horizons. Their field trips grow more frequent and numerous, covering a broad range of topics, exposing Azriel to more and more art. They see dance recitals and theatre performances, travelling troupes and local players both; Russian ballets, cirque acts from China and flamenco dancers from Spain. They visit museums, and galleries, with DeVry often calling in special favours to allow he and his young protege to wander the halls of galleries after closing hours. On one particularly memorable night, Azriel loses himself for a full twenty minutes in front of Reni’s Saint Sebastian, in London on loan, hand stalled halfway between his heart and the canvas as though desperate to touch. When DeVry touches his shoulder to tell him it’s time to go, his legs buckle, and he falls to his knees on the cool marble floor, weeping. (He develops an appreciation for painting and drawing, especially, although he has no talent of his own to speak of in that department; DeVry arranges to have some texts on art history and theory delivered to the campus, and provides them to Azriel as an end of year gift.)

And always, of course, the thread of music running through them—a standing box seat at the London Opera, reserved seats for the inaugural performance of the symphony’s seasonal shows. Azriel soaks it all in, revels in it, indulges in it. It’s clear he can’t get enough, trying to take it all in with wide-eyed wonder. DeVry grows used to his habit of leaving a venue teary-eyed and quiet; knows that by the time they are halfway back to campus, Azriel will be excitedly breaking down the experience, sharing his observations, and asking myriad questions.

For Azriel’s part, he feels treated as an equal, on those trips. Special; uniquely deserving. DeVry listens carefully as he tries to sort through his thoughts and emotions around a particular work or performance, asks him difficult questions about the nature of the art, inviting him to get philosophical with it even when Azriel is unsure of the correct theories or schools of thought, and is a constant source of positive reinforcement— So bright. So thoughtful. Such passion. Such wisdom. You are wise beyond your years, Azriel. An old soul. I’m grateful every day that I have been granted the gift of knowing you.

* * *

Of course, Azriel is still a prideful little thing, still haughty and distant from his classmates; and being the recipient of special attention such as DeVry’s, when the man is such a source of terror to many of his classmates, doesn’t help matters. If anything, it inflates his ego further, making him even more a target for ridicule and teasing. He does his best to ignore this, however; tells himself he is safe and secure in DeVry’s regard, despite living in an ever-present fear that one day, this attention will be taken from him; that he will be returned to, not anonymity, but the role of the outcast, with nothing but his own pride with which to support holding his head high.

With the attentions paid to him by both DeVry and by Alastair, Azriel comes to a profound realization of his own character—he loves to be be admired . It’s not new to him to want attention—he’s known, subconsciously, since the first day of school how desperately he needs the attention of others. But admiration is a new one for him to experience, and he finds it addicting. So he determines to work harder, to continue to push himself, to excel, all for the reward of seeing surprise and pride in DeVry’s eyes at their lessons. He even, to some degree, starts to seek that validation from his peers and the faculty; craving that feeling of admiration, and feeling its absence when he is forced to go too long without attention from one or the other.

With Alastair, it’s less of a matter of seeking admiration; it comes so much more naturally. He gives attention to Azriel as though from a bottomless fountain; where DeVry dishes it out in measured, rationed cups, Alastair fills up the bucket for him and invites him to drink deeply, and he does, oh he does. He will ask so earnestly after the details of Azriel’s outings—never with a hint of jealousy or envy—and Azriel takes a great deal of pride in sharing them with him, painting vivid images with his words. He relates the plays, ballets, and operas with Alastair like a storyteller, and gets drunk on the way Alastair hangs on every word, enraptured with a world of storytelling he hasn’t had much chance yet to encounter. He describes the way the music, or the dance, or the brushstrokes are used by their wielders—cribbing from DeVry’s tutelage, not that he thinks Alastair would mind—and the other boy looks at him in wonder, like he hung the moon, asking wide-eyed and curious questions, repeating details back to be sure he has the stories right. Sometimes, he just sits, silent and at peace, while Azriel softly sings the tune of the aria from last night’s opera, or the melody line of the violin concerto, as though his voice could capture for Alastair the same emotion it evoked in him the night before.

In those moments, Azriel looks at him like the painting of Saint Sebastian, and feels like his knees might give out all over again; he pictures the boy’s body pierced with arrows, imagines catching the trickling blood in a cup, sharing in that communion, and he misses an interval, coming down flat on the next note. Alastair doesn’t notice; just waits patiently, hands clasped between his knees, for Azriel to finish regaling him with the story of his latest night out.

1 note

·

View note

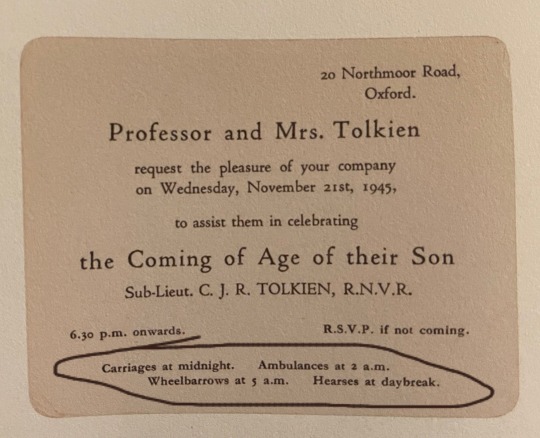

Text

"our son made it through the war to come of age, let's fucken party! rsvp only if you're a little bitch who's NOT coming. all y'all not dead of alcohol poisoning by morning (lmao losers) get dunkt on"

69K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fool's Fate, Robin Hobb

The Song of Achilles, Madeline Miller

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

I have my Aggie notebook (you may have seen it posted here before) into which I have committed to putting everything related to this trash heap of a character. That means that every post I have here on Tumblr, I have handwritten/copied down into the notebook.

Except then I blacked out and wrote 4k words of smut. Now--I need it in the notebook, because I don't do things by halves and I have extremely black and white, all or nothing thinking when it comes to things like this. But I don't really want to handwriting that many words of smut and take up valuable page real estate.

My solution? Apparently, it was to print and bookbind the silly thing, so I can tuck it inside the pocket at the back of the notebook and maintain my commitment to the bit keeping everything Azriel Edgemont-related in one place!

This is now a thing I have in my house. What is wrong with me.

7 notes

·

View notes