bantarleton

28K posts

"Slaughter was commenced before Lieutenant-colonel Tarleton could remount another horse, the one with which he led his dragoons being overturned by the volley… The loss of officers and men was great on the part of the Americans, owing to the dragoons so effectually breaking the infantry, and to a report amongst the [Loyalist] cavalry, that they had lost their commanding officer, which stimulated the soldiers to a vindictive asperity not easily restrained."

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

youtube

It seems we have a new Tarleton/Tavington video!

#history#british army#military history#18th century#american revolution#redcoat#american war of independence#revwar#redcoats#tarleton#tavington#the patriot#Youtube

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

And in miniature form by Jasper Oorthuys.

A brilliant portrayal of British Captain Patrick Ferguson's experimental rifle corps, an ad hoc company raised in 1777 and equipped with Ferguson's famed breech-loading rifles.

279 notes

·

View notes

Text

Classic second battalion.

#history#military history#18th century#american revolution#redcoat#american war of independence#revwar#redcoats

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

Image: IWM (Art.IWM ART 1609)

Two British soldiers picking apples in an orchard. The soldier on the left bites into the fruit as he looks around him, while the other, wearing a kilt, leans up to pick from the higher branches.

278 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

A new video exploring the use of riflemen by British forces during the American Revolution. A follow up to this one about American long rifles.

#history#british army#military history#18th century#american revolution#redcoat#american war of independence#revwar#redcoats#rifle#riflemen#rifles#gunblr#musket#muskets#Youtube

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Highlights from this year's Lexington and Concord re-enactment - the high quality on display here means hopefully next year's 250th is going to be excellent.

#history#military history#18th century#american revolution#american war of independence#revwar#Youtube

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

The band of the Scots Guards at this year’s Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo.

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Redcoat History has a new RevWar video up, busting some myths about rifles during the American Revolution.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Volunteers of Ireland, you are fine fellows! Charge the rascals - by heaven you behave nobly!”

— Earl Cornwallis rallies the Volunteers of Ireland at the battle of Camden. One officer recalled how ‘our regiment was amazingly incited by Lord Cornwallis, who came up to them with great coolness, in the midst of a heavier fire than the oldest soldier remembers.’

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

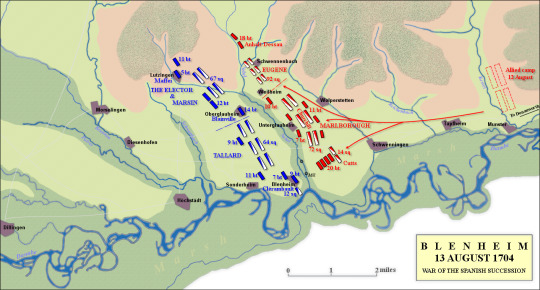

Prussian, Danish, Austrian, Dutch and British allied forces at the battle of Blenheim.

137 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Battle of Blenheim, August 13th 1704.

On this day, one of the most important battles in British history took place. Although not quite as well known as it deserves to be, it was crucial for preventing France under Louis XIV, the notorious ‘Sun King’ from becoming as powerful as Napoleon was at the height of his power. It also cemented the reputation of John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, ancestor of Sir Winston Churchill, a figure who would himself play a decisive role in a future British war against a different continental enemy.

The War of Spanish Succession

The War of Spanish Succession had been precipitated by the death of Charles II of Spain, last of the Spanish Habspurgs in 1700, who had bequeathed the throne to Philip, Duke of Anjou, who belonged to a cadet branch of the French Bourbon dynasty. However, the throne was also claimed by Archduke Charles of the Holy Roman Empire, son of Leopald I, Louis XIV’s long standing enemy. Louis XIV’s enemies viewed a Bourbon on the throne of Spain, with it’s vast Empire, as unacceptable, in the same way Louis XIV viewed being encircled by rivals and enemies as similarly unacceptable. England (later part of Great Britain) entered the war in 1702 alongside its Dutch and other allies in order to prevent a nightmare scenario whereby Louis XIV, a lifelong enemy of England and Holland, would get to preside over a continental superpower consisting of the most populous nation in Europe and its largest and wealthiest Empire.

Marlborough’s March South

At the beginning of 1704, the war was not going very well for the allies. The French were pushing the Austrians back across Italy into their heartlands, at the same time Leopold I, the Holy Roman Emperor was facing a rebellion in Hungary, and Bavaria, a technical vassal of Leopold I, had declared in favour of France in order to protect their governorship on behalf of Spain in the Spanish Netherlands. John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, in command of Anglo-Dutch forces in the Netherlands, wanted to march south along the Rhine in order to confront the threat to Vienna, which if it had been captured, could knock Austria out of the war and thwart the balance of power England sought on the continent for its own security. The Dutch however, where cautious, and refused him permission to take his troops away from the Dutch frontier where they feared an invasion by French forces.

Marlborough plotted in secret to take English forces and march south anyway, whilst deceiving both his Dutch allies and the French of his intentions, who initially believed he was planning to attack French forces in the West. However, he turned South and East along the Rhine, presenting the Dutch with a fait accompli. They could either march with Marlborough, or run the risk of his army being defeated without Dutch help and therefore leave them isolated and unable to resist a French invasion.

And so on May 19th, Marlborough set out to follow the Rhine with 21,000 men (including 16,000 British troops), to be joined along the way by allies from Denmark, Prussia, Hanover, Saxony, Austria and Hesse. The journey was fairly rapid, despite the poor roads and often poor weather, as Marlborough had taken care to plan ahead and set up supply depots along the way in order to speed the advance up and avoid alienating the local populace by looting them for supplies, as the French typically did. As Marlborough intended, the march south also drew French troops away from the Dutch frontier, much to the relief of the Dutch Government.

Marlborough was later joined by Prince Eugene of Savoy, a Frenchman by birth who had once sought employment in the French Army, only to be rebuffed, and so had entered Austrian service instead. In the meantime, Tallard, Marshall of France, was marching east through the Black Forest in order to link up with Bavarian forces and defend against Marlborough and Eugene.

The Armies Deploy

The two armies eventually met near the village of Blenheim (also known as Blindheim) on the 12th of August, and the two allied commanders resolved to attack Tallard’s forces the following morning.

Tallard had placed his army on high ground in front of a marshy stream called the Nebel, which allied forces would have to cross in order to confront Franco-Bavarian troops on the ridge ahead,. In addition, Tallard was able to anchor his right flank by garrisoning a substantial force within the Village of Blenheim next to the River Danube, whilst his left flank was partially protected by heavy woodland and the village of Lutzingen, along with another settlement called Oberglau just to the left of Tallard’s centre, which was also garrisoned and barricaded. Tallard also slightly outnumbered the allies, with 60,000 men compared to 56,000 on the allied side, as well as 90 artillery pieces to the allies 66.

Conventional wisdom would have suggested that an allied attack under such circumstances would be madness, but Marlborough and Prince Eugene decided that such conventional wisdom, if adhered to by Tallard, would inspire complacency in the French and their Bavarian allies, as the last thing the enemy would be expecting was an attack uphill against their superior numbers and fire-power.

The Battle Begins

At 7 AM the following morning, the French observed the allied army approaching to attack, and organised their units into position. At 11 AM, the battle commenced when the French batteries opened fire on the allied lines. Fortunately, many of the troops were partially obscured by unharvested crops growing in the fields, which made it much harder for French gunners to direct their fire towards them. Marlborough ordered his men to lie down in order to protect them from the full effects of the bombardment, and was himself almost killed when a French cannonball ricocheted off the ground underneath his horse. Marlborough waited until Prince Eugene’s forces where in position before he would commence the attack.

As both sides exchanged artillery fire, Prince Eugene was busy deploying his forces to the allied right. At 12:30 a message arrived from the Prince informing Marlborough that his forces where finally in position and that the allied assault could begin. Rowe’s Brigade commanded by Scotsman Archibald Rowe attacked the French right barricaded in Blenheim, with Rowe himself fearlessly leading the charge from the front. He ordered his men to hold fire until he could strike the walls of the village with his sword. Rowe managed to survive long enough to reach the wall and smack his sword against it, but fell mortally wounded soon after, as did two of his aides who dashed forward to try and rescue him. The British opened fire with their muskets, but the attack was repulsed and they were forced back. A French counter attack was however in turn repelled by steady volleys of British platoon fire that drove the French back behind the walls and barricades of Blenheim. An attack by Tallard’s cavalry attempting to role up the British infantry was also repulsed. After a period of reorganisation and rallying, the British left, under the command of Major-General Lord Cutts renewed the assault on Blenheim, but they were forced back once again. However, the attack did panic the commander of the French right, Marquis de Clerambault into moving no less than 27 French battalions or 12,000 men into the village to ensure that it was held, packing them in so tightly that they made easy targets for allied guns and muskets, whilst they in turn could not bring their own muskets fully to bear against the redcoats. It also meant they could no longer support nearby French cavalry effectively.

The two failed assaults had caused heavy casualties however, and Marlborough ordered Cutts to cease his attacks and hold his position in order to keep the French penned up in Blenheim whilst he advanced his centre forces across the Nebel and the marshy ground to assault the French centre as Eugene attacked from the right and kept the Franco-Bavarians occupied there.

Attack on the Centre

Tallard allowed British forces to cross the Nebel relatively unmolested except for some artillery harassment. He hoped that by allowing them to cross the stream and over the marshy ground that they would be trapped and unable to escape quickly across the marshland, allowing him to smash the allied centre with a devastating counter-attack.

Despite a concerted attempt by the French cavalry and supporting infantry to attack Marlborough’s infantry in the centre and open up a flank on the right of the British left, the attack failed and the French cavalry was repulsed by a counter attack from British cavalry, though they themselves were compelled to fall back temporarily in the face of heavy French musketry when they advanced too far in pursuit.

Prince Eugene’s Assault

Prince Eugene’s initial attack on the French left near Lutzingen met with limited success. Although the Dutch, Danes and German forces under his command managed to drive the Franco-Bavarians back , even to the point of reaching the enemy’s cannons and engaging in hand to hand combat with French artillerists, they were driven off by a counter-attack from the enemy’s infantry. The enemy gunners swiftly brought their cannon back into action, deploying them as giant shotguns unleashing a storm of canister that shredded its way through Prince Eugene’s retreating forces, causing horrific casualties. Despite the failure of Prince Eugene to make a breakthrough, his attack did serve to tie up much of Tallard’s left flank and distract them from Marlborough’s main attack through the centre.

The Collapse of the Franco-Bavarian Army

In the centre, a renewed allied assault finally broke the French cavalry, who, overcome with panic, began to flee the battlefield across the plain and over the Danube River to the South, where many of them drowned. As the French cavalry ran, 9 battalions of French infantry, now unsupported by cavalry and therefore trapped, were bombarded without mercy by Colonel Blood’s (son of the notorious Tower jewel thief) artillery, until they themselves broke and ran, only to be pursued and cut down by English and allied cavalry. During this rout, Marshal Tallard himself was captured, as Eugene’s forces on the allied right and Marlborough’s forces on the left advanced on the villages of Luzingen and Blenheim respectively.

Faced with an irresistible onslaught backed up with artillery, the Franco-Bavarians set fire to Lutzingen and Obergrau to cover their retreat before withdrawing. As Eugene advanced, the English began to envelop Blenheim, which was still holding out even as the rest of Tallard’s forces were being driven from the field.

Assault on Blenheim and French Surrender

Although Blenheim was still heavily garrisoned with French troops, they held on with dogged determination, forcing the British to fight a vicious and brutal close quarters struggle with bayonet, bullet, butt and fist from house to house and street to street. Eventually, they managed to drive the French into a walled Churchyard and its surrounding buildings. At this point, much of the village was in flames, partly through the constant gunfire, but also through deliberate arson on both sides as they tried to flush the enemy out with fire or obscure their manoeuvres. Many troops on both sides, particularly the wounded, suffered a grisly fate, consumed by the flames where they lay helpless and unable to escape.

By this point, Clerambault was missing, presumed dead and what was left of the French garrison was commanded by the Marquis de Blanzac. During a brief truce agreed between both sides in order to recover their dead and wounded, the French learned that their commander in chief had been captured and the rest of their army had fled from the field. As night fell, Blanzac, persuaded of the hopelessness of his position, agreed to surrender the remaining 10,000 troops under his command. The battle was over.

Aftermath

The allied victory was decisive, but had come at a heavy cost. 14,000 allied troops had been killed or wounded, but the French and Bavarian forces had for their part lost 20,000 dead or wounded with a further 14,000 taken prisoner. What was left of the enemy army limped back to Strasbourg, haemorrhaging several thousand more troops through desertion along the way.

French plans to take Vienna were in ruins, as was the nigh on invincible reputation of Louis XIV’s forces. News of the stupendous victory reached England on the 21st of August, amidst much rejoicing from Queen Anne, Parliament and the people. A grateful nation granted the triumphant Duke money and land with which to build a sumptuous palace, known as Blenheim Palace, after the battle that proved to be the Duke’s greatest triumph. Although the war was far from over, it had put the French on the back foot and the Sun King’s hopes for a peace in his favour were dashed. It would take many more years and many more battles before the war ended in the allies favour with the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, followed by the Treaty of Rastatt between Louis XIV and Leopold I the following year. Although perhaps not as decisive in its own right as other more well known battles such as Waterloo and Agincourt, Marlborough and Prince Eugene’s victory at Blenheim had arguably saved the allies from defeat by preventing the French from knocking the holy Roman Empire out of the war and forcing an unfavourable peace on the allies that would have left the Sun King stronger than ever. It might be said that although this battle was not decisive in the sense of destroying the enemy, if this battle had been lost, or not fought at all, Britain would not have been able to achieve its later successes. For this reason, Blenheim must surely rank amongst British history’s most notable battles.

153 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm trying to get into this time period, specifically the British. How would you describe Ban's personality? Is he as cruel as some sources make him out to be?

Welcome to the period!

I wouldn't say cruel no, certainly not to the degree of the "Butcher Ban" myths. But he could be very arrogant and overconfident. Was he a good guy? Not by today's standards. He could be a vicious enemy, but was also charming and a good friend.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Redcoat History has a new RevWar video up, busting some myths about rifles during the American Revolution.

#history#military history#american revolution#18th century#american war of independence#revwar#rifle#rifles#gunblr#firearms#Youtube

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Battle of Bushy Run by Robert Griffing.

On August 5 1763, near the Bushy Run Way Station, Henry Bouquet and his 400 men, many of them Scottish highlanders, were ambushed in the wilderness by various Native American tribes including the Delaware, Shawnee, Mingo, Wyandot, Miami, Ottawa, and Mohicans. The first day of the battle ended in a decisive victory for the Native American tribes, but on August 6, Bouquet devised a strategic plan that led to a British victory. Following the Battle of Bushy Run, Bouquet went on to provide successful assistance to the besieged Fort Pitt. From the Bushy Run Battlefield Museum.

#history#british army#military history#18th century#redcoat#redcoats#scotland#scottish#scottish history#highlander#highlanders#pontiac's rebellion#seven years war#french and indian war

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

French grenadier drummer, 1790s by Maurice Orange.

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

The two oldest commissioned ships of the World - USS Constitution (227 years old) and HMS Victory (259 years old)

1K notes

·

View notes