TODOS | ULTRA LUXURY GOODS | EATING & READING | RACE & GENDER & CLASS | ARCHITECTURE & URBANISM & ENTROPYTRAVEL & ECOCIDE | EARTH'S CRITTERS | H2O | CLASSIFIED (INFORMATION) | SPORTS i.e. BRAINWASHINGVOLUNTEER | PRESS WEBZONE | PUPPETS!!! | ugh CONTACT us if you must ughhh | ETHICS POLICY written by wimptown & shet272 | montreal & everywhere

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Big Beautiful Wall: Architecture and Ethics in the Divided States of North America

Approaching the borderwall as architecture means looking at its real and intended program. In this way, value judgments cannot strictly be separated from the function of the borderwall itself. Judgments about the wall are inevitably ethical judgments. I begin with a brief social context of the borderzone to understand the ideological forces behind real and imaginary walls. I then investigate a range of discursive statements by which these walls are considered beautiful. The critical and theoretical reception of the Big Beautiful Wall has been well-documented, and can roughly be separated into two camps: populist and emancipatory.

One the one hand, Trump’s espousal represents the mainstream, populist conception of the borderwall as a necessary and effective barrier of social ills. Even statements about the imaginary wall becomes both the symptom and cause of populist, xenophobic myths within and beyond the borderzone. Trump’s is the dominant discourse which has constructed the actually-existing barriers onto which is projected the trajectory of the Big Beautiful Wall to come, for many criticisms of the Big Beautiful Wall critique only its practicality its designs and not the underlying ethics.

The other discourse under consideration is that of the activist-architect, informed by postcolonial mobility studies, which I have called the emancipatory position. Within the debates of borderculture, architectural theory, criticism and activism there is a brewing movement to counter populist conceptions of the borderzone. The Big Beautiful Wall and the existing border architecture becomes the subject and site of a new critical stance towards its underlying ethics of exclusion, with architects questioning even the perceived neutrality of nonparticipation in design of border infrastructure. The discourse is shifting under the influence of the new ideas and their disseminations, intervening in the mainstream imaginary and recasting both the border barrier and resulting in new more emancipatory paradigms of international limits.

The borderwall is nestled in the borderzone of a bi-national borderculture, 84% urban, with a current population of 15 million people, and projected to rise to 20 million by 2020. The borderzone can be best imagined as 15 pairs of sister cities strung out along an arbitrary line between the Pacific and the Gulf of Mexico [fig. 3]. The Big Beautiful Wall is the object which most influences the rest of the borderzone. In the struggle between these two opposing visions of the borderwall we can also imagine the wall less as an architectural intervention nor as a mechanism of social engineering but, as Bruno Latour and Bill Brown has suggested, “quasi-object” and “quasi-subject.” Together with human agents, the Big Beautiful Wall contributes to forming the component parts of the organization of the “temporality of the animate world,” both within and beyond the borderzone itself. The real and imaginary borderwalls are not merely the merger of the symbolism of the Great Pyramids and the functional austerity of a nuclear waste dump, but perhaps the subjects who themselves “think” borderculture, evidenced only in a small glimpse within the discourses investigated herein.

Investigating the judgments of the Big Beautiful Wall it is first necessary to look at the 654 miles (1,046 kilometers) of existing border fortification in the US/ Mexico limit, the physically existing borderzone between the United States of America and Mexico. As describe by the Pan-American Health Organization, the borderzone between the United States and Mexico:

represents a binational geo–political system based on strong social, economic, cultural, and environmental connections governed by different policies, customs, and laws [which determine] commerce, tourism, sister–city familial ties, Mexico’s assembly plants or maquiladoras (plants that import components for processing or assembly by Mexican labor and then export the finished products), ecological services, a shared heritage, social partnerships, and immigration.

Though the two nations have shared this space since 1847 until 2006 only a few dozen miles were fenced. Before 2006 the borderwall took many forms, from “an imaginary line marked with some scatter monuments to a light barbed fence, to a wire grid, to a heavy metal wall, until becoming what it is today: series of aggressive metal fences and enormous concrete posts.” The major shift in US security after 9/11 recast the undefended border as major security vulnerability and the U.S. Secure Fence Act of 2006 mandated the construction of 700 miles of borderwall. Inspired by [and longer than] the so-called Israeli Security Fence—“walls work, just ask Israel”—the major difference is that the Israelis’ wall objective is to stop all people while the actually-existing borderwall merely hopes to slow down people crossing in order to allow them to be apprehended. Since 2006 over 700 miles of barrier fortifications were built and maintained at the cost of $49 billion USD over twenty-five years [fig. 4]. Approximately one-third of the US/Mexico frontier is walled or fenced, featuring 11 different types of wall. Each day the border has 13,300 commercial trucks cross it.

Starting in 2006 the purpose of the borderwall was to enact a limit on America, as if it could be sealed like a ziplock bag. As the Washington Post describes, “[t]he message from Congress was clear: Building a physical barrier was an acceptable and even desirable policy solution to illegal immigration.” More than a decade later, this is still the mainstream policy: And of course, candidate Trump promising campaign rallies the construction of an “impenetrable and beautiful” wall. However Senator Ted Cruz, R-Texas, in his failed campaign, also promised a wall stating the “unsecured border with Mexico invites illegal immigrants, criminals, and terrorists to tread on American soil,” and repeating the same populist security concerns. As President, Trump tweeting that the Big Beautiful Wall will “help stop drugs, human trafficking etc,” and calling the day he signed two executive orders regarding the wall the first day of America “get[ting] back control of its borders,” implying there is no control at present. Trump goes on to opine that the wall would “help Mexico” by deterring migrants from South America passing through Mexico on their way to the United States, and would one day “thank us” for its construction. To call this borderwal acceptable, desirable or beautiful is an inherent value judgment about the functions it serves vis a vis its real, perceived and symbolic function regarding security and social engineering.

The implication is that biopower is beautiful. In the populist imaginary the Big Beautiful Wall is a site of domination over Mexico and over geography itself, where political power obliterates even nature. The populist conception of the Big Beautiful Wall is almost a utopian surrogate to the actually existing one, where the borderwall is a gleaming emblem of reified security. The first type of criticism of the Big Beautiful Wall under consideration is concerned more with the lack of pragmatism in its program. The cost and expanse of the project leaves “mainstreamers … always believed the Wall was a fantasy, a campaigning prop.” The idea of fantasy or allegorical nature of the Big Beautiful Wall as it came to life on the campaign trail is thought to be “tactical symbolism.” These pragmatic criticisms are perhaps most succinctly phrased by former Homely Security Secretary Jeh Johnson, who quipped: “It makes no sense to build a 10 foot wall on top of a 10,000 foot mountain.” What these criticism all share is a tacit endorsement of the borderwall’s objectives, but a suspicion of its feasibility. In this view, the objection is less with the ethics of the borderwall than its practicality.

A second and more profound form of critiquing the Big Beautiful Wall is from an ethical perspective. Texas congressional Rep. Castro [D-El Paso] said, “[t]he future of border security lies … not [in] medieval defenses.” But in deeming the wall medieval, he is suggesting that the wall is barbaric, brutal, cruel and just plain ethically wrong, or just technological primitive? Rep. O’Rourke, [D-El Paso] goes a little deeper into ethical territory by stating: “This wall makes sense if you’re not from here … if you’re scared of Mexico and of Mexicans. It seems like a good emotional response to that fear. [But when you live here] … it seems ridiculous, shameful and embarrassing.” Perhaps some of that embarrassment and shame is that the Big Beautiful Wall risks dividing other already marginalized indigenous communities within the borderzone, numbering approximately 130,000 people along the Mexican side and 80,000 on the US side. Proposed path cuts through Tohono O'odham land, among the largest indigenous reservations. Shameful that the borderwall and patrols have influence where attempted crossings can be made, areas “likely to lead directly to increased number of deaths. […] Since shooting illegal border crossers is not an option… the bureaucratic solution… is to push them into locales where nature pulls the trigger.” From this perspective, the Big Beautiful Walls is the shameful inheritance of a global politics predicated on division and exclusion.

Unpacking the ethical considerations of walling to architects inevitably passes through German during the Cold War. Perhaps surprisingly, the idea that there is beauty to be found in the biopower is also shared by architect and prominent self-proclaimed public intellectual Rem Koolhaas. Writing in 1993 about the Inner German Border [1952-199O] [fig. 5] and the Berlin Wall [1961-1989] [fig. 6], Koolhass discovered:

The greatest surprise: the wall was heartbreakingly beautiful. Maybe after the ruins of Pompeii… it was the most purely beautiful remnant of an urban condition, breathtaking in its persistent doubleness. […] It was impossible to imagine another recent artifact with the same signifying potency.

Koolhaas’ analysis casts the wall’s function of biopolitical control as an ethical concern, where “The wall suggested that architecture’s beauty was directly proportional to its horror.” The horror Koolhaas invokes the power of architecture’s which he enumerated in a numbered collection of judgments, the most crucial of which was that the borderwall “was a very graphic demonstration of the power of architecture and some of its unpleasant consequences.” Koolhaas also states the “significance as a ‘wall’—as an object—was marginal; its impact was utterly independent of its appearance. Apparently, the lightest of objects could be randomly be coupled with the heaviest of meanings through brute force, willpower.” However, Koolhaas also found in the German case a magnificent ingenuity to the hand-dug tunnels, artisanal aircraft and ingenuous hideaways in automobiles. In regards to the Big Beautiful Wall, similar inventive subversions are to be found: catapults which toss drugs over the borderwall, ramps for jeeps and trucks to drive over.

Clearly, the architecture of the Big Beautiful Wall is implicated as being as “horror” in its own right. The poet Gloria Anzaldúa wrote of the US-Mexico borderzone as the place “where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds.” These views align with activist-architects who intervene into the populist imaginary of the Big Beautiful Wall and recast it as a potentially emancipatory zone of exchange, hybridity, and ingenuity. In research performed by architects with a taste for postmodern reflexivity and postcolonial poststructuralism, the wall here is cast not as a barrier as in the populist view but, influenced by postcolonial stance in migration studies, is seen as dividing two nations and uniting a third nation around it. As explained by Ronald Rael:

there is no question about the spatial, psychological, social, and architectural repercussions of this barrier. As an architectural intervention, the wall has transformed large cities, small towns, and a multitude of cultural and economic biomes along its path, creating a Divided States of North America, defined by some as a no-man’s land band by other as a Third Nation.

No doubt informed by Koolhaas’ assertion that the Berlin Wall “was a script, effortlessly blurring divisions between tragedy, comedy, melodrama,” these architects imagine rewriting that script to create a more empowering borderzone, real and imaginary. Now turning to briefly look at emancipatory alternatives to biopolitical borderwalls. architect Teddy Cruz and political scientist Forman have lead the charge of an empowering reinvention of the borderzone happening alongside its actual construction over the past decade. Immensely influential actions by the pair as Estudio Cruz + Forman include The Political Equator, an infographic which turned into a series of workshops; their participatory, relational aesthetic intervention when they turned a drainage pipe into an official border crossing for a day; and their seminal research into recycling material from California making its way into construction in Tijuana [fig. 7 and 8]. Rather than architects, landscape architects and urbanists “decorating the mistakes of stupid planning,” with architectural interventions which only “camouflage the most pressing problems of … today.” The Big Beautiful Wall—even before Trump spoke those words—was already the focus of Cruz and Forman’s work. As they state: “to be political in our field suggests a commitment to exposing the conditions of conflict inscribe in a particular territory and the institutional mechanism that have perpetuated such conflict.” The borderwall is the ultimate institutional mechanism at play in the boderzone. In relation to the Big Beautiful Wall, Forman reminds us:

The physical barrier is one way to understand the divide that exists, somewhat arbitrarily, between the two countries. But it’s important to know that the border is reproduced in multiple ways—physically, socially, and psychologically—in other parts of both countries. The border has always been a way of reinforcing antagonism that doesn’t always exist. In many ways, it’s artificial. But it has been hardened into norm.

MADE Collective and Ronald Rael no doubt are influenced by Cruz+ Forman’s influential call for “[c]reative practices need to infiltrate existing institutions in order to transform them from the inside out, producing new aesthetic categories that problematize the relationship between the social, the political, and the formal.” Both their MADE and Rael’s projects are informed by this seeping into the institutions of the borderwall to transform it from the inside out. MADE Collective has submitted an official application to use a portion of the wall’s budget to instead build a transportation network and remove the wall. They describe the Big Beautiful Wall as “more a signifier of status than a barrier.” Ignoring the barrier potential of the wall, MADE instead suggest creating a new country of Otra in the borderzone, bound together by the Hyperloop transportation system [fig. 9]. Ronald Rael has also contributed immensely to the discourse on reinventing the Big Beautiful Wall. In nearly a decade of research and research-creation, summed up in his recently published Borderwall as Architecture, which Rael describes as a “protest against the wall—a protest that employs the tools of the discipline of architecture manifested as a series of designs that challenge the intrinsic architectural element of a wall charged by its political context.” Rael offers a satirical detournement of border fortification design, offering instead of a barrier the ability to share a burrito through the wall, play a game of volleyball [“wall-y ball,” fig. 10] over the wall, divide nations with green infrastructure projects or enjoy a gentle teeter-totter experience within the structure of the wall itself [fig. 11].

**

The populist call lead by Trump to transmutate the Big Beautiful Wall into reality is underway. A tender has been offered to build two types of prototypes—one of reinforced concrete and one of materials of the designer’s choosing. Both must be 30-feet tall though 18-feet could be acceptable. The Big Beautiful Wall must be “aesthetically pleasing in color,” at least on the American side. Ten selected prototypes will be announced this June by the United States Department of Customs and Border Protection, each to be built in 30-foot segments in the desert to be tested with ramming, cutting, ramping and climbing. Secretary of Homeland Securirty John Kelly has explained, “It’s unlikely that we will build a wall or physical barrier from sea to shining sea,” but it seems inevitable that more borderwall—perhaps up to $21.6 billion-worth—will be built. In 1989 before they danced in Berlin there were 15 border walls on the face of the earth while today there are 70. The Berlin Wall, the Israeli Defensive Fence and especially the imaginary Big Beautiful Wall are all better walls than the one which exists between America and Mexico. The Big Beautiful Wall is the symbolic spectre of the USA’s might, a dematerialized boogeyman, the projection of total control in a realm where total control is impossible. A deeper understanding of this typology is needed to understand the forces of biopower within global flows. Tensions present even in the imaginary border wall of the future are not just about two specific countries but the tensions between the core and periphery itself. In this regard, the shadow of the Big Beautiful Wall falls on us all.

Bibliography

Bierman, Noah and Brian Bennett. “Trump’s ‘big beautiful wall’ is not in the spending plan. Will it ever get built?” Los Angeles Times. Published 1 May 2o17, accessed 3 May 2o17, http://www.latimes.com/politics/la-na-pol-trump-wall-20170501-story.html

Brown, Bill. “Thing Theory,” Critical Inquiry, no. 28.1 (Autumn, 2001)

Calame, Jon and Esther Charlesworth. “Cities and Physical Segregation.” In Divided Cities: Belfast, Beirut, Jerusalem, Mostar, and Nicosia. Philadelphia; University of Pennsylvania Press, 2oo9.

Citton, Yves. “Populism and the Empowering Circulation of Myths.” Open! DEETS. Published 17 January 2o11

Corchado, Alfredo. “Common Ground: Poll finds U.S.-Mexico border residents overwhelmingly value mobility, oppose wall,” Dallas Morning News, published 18 July 2o16, accessed 21 May 2o17, http://interactives.dallasnews.com/2016/border-poll/

Cruz, Teddy. “Untitled.” In Urban Future Manifestos. Eds. Peter Noever and Kimberli Meyer. Ostfildern; Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2o1o. A production of the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, Los Angeles MAK Urban Future Initiative. 56-57

Cruz, Teddy and Jonathan Tate. “Design Ops—A conversation between Teddy Cryz and Janathan Tate.” In Architecture at the Edge of Everything Else. Eds. Esther Choi and Marrikka Trotter. Cambridge, Mass., London, England; The MIT Press. 74-83. 2o1o.

D’Alleva, Anne. “CHAPTER,” Methods and Theories of Art History. Second edition [London, Laurence King, 2012]

Diamond, Jeremy. “Trump orders construction of border wall, boosts deportation force,” CNN, published 25 January 2o17, accesed 15 May 2o17, http://www.cnn.com/2017/01/25/politics/donald-trump-build-wall-immigration-executive-orders/index.html

Di Cintio, Marcello. “Pilgrims at the Wall.” In Borderwall as Architecture: A Manifesto for the U.S.-Mexico Boundary. Oakland; University of California Press, 2o17.

Huyssen, Andreas. “World Cultures, World Cities,” in Other Cities, Other Worlds. City, Duke University Press. 2oo8.

Iglesias-Prieto, Norma. “Transborderisms: Practices That Tear Down Walls,” In Borderwall as Architecture: A Manifesto for the U.S.-Mexico Boundary. Oakland; University of California Press, 2o17.

Jan, Tracy. “Trump’s ‘big, beautiful wall’ will require him to take big swaths of other people’s land.” Washington Post. Published 21 Mars 2o17, accessed 3 May 2o17, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/03/21/trumps-big-beautiful-wall-will-require-him-to-take-big-swaths-of-other-peoples-land/?utm_term=.3a3e889c6b93

Jones, Reece. “Death in the Sands: the horror of the US-Mexico border.” The Guardian. Published 4 October 2o16, accessed 21 May 2o17, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/oct/04/us-mexico-border-patrol-trump-beautiful-wall

Joshi, Anu, “Donald Trump’s Border Wall – An Annotated Timeline.” Huffington Post. Published 28 February 2o17, updated 1 mars 2o17, accessed 12 May 2o17, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/donald-trumps-border-wall-an-annotated-timeline_us_58b5f363e4b02f3f81e44d7b

Koolhaas, Rem. “AA Memoir: The Berlin Wall as Architecture.” In S, M, L, XL, Rem Koolhaas, OMA and Bruce Mau. DEEEETS.

Koolhaas, Rem, AMO, Harvard Graduate School of Design and Irma Bloom. “Defensive Wall.” In Elements of Architecture – 14. International Architecture Exhibition, la Biennale di Venezia: Wall. Published DEETS. Page etc.

Lartey, Jamiles. “Trump: Russia inquiry distracts from running the US ‘really, really well’—as it happened.” The Guardian. Published 18 May 2o17, accessed 18 May 2o17, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/live/2017/may/18/donald-trump-russia-robert-mueller-live

Levin, Bess. “Trump’s Big Beautiful Wall is Already Running Billions Over Budget,” Vanity Fair, published 1o February 2o17, accesed 17 May 2o17, http://www.vanityfair.com/news/2017/02/trumps-big-beautiful-wall-is-already-running-billions-over-budget

Livingston, Abby. “Texans in Congress offer scant support for full border wall,” Texas Tribune, published 2o Dec 2o16, accessed 21 May 2o17, https://www.texastribune.org/2016/12/20/where-texas-congressional-delegation-stands-trumps/

Macchi, Victoria. “Hundreds of Bids Submitted for US-Mexico Border Wall Prototype.” Voice of America News. Published 3 May 2o17, accessed 3 May 2o17, https://www.voanews.com/a/hundreds-of-bids-submtted-for-us-mexico-border-wall-prototype/3836695.html

MADE Collective, “Otra.” Accessed 12 May 2o17, url

Maril, Robert Lee. “Crossing to Safety.” In The Fence: National Security, Public Safety, and Illegal Immigration. DEETS

Misra, Tanvi. “‘The Border Is a Way of Reinforcing Antagonism That Doesn’t Exist.’” CityLab / The Atlantic. Published 11 January 2o17, accessed 22 May, 2o17, https://www.citylab.com/equity/2017/01/the-urban-laboratory-on-the-san-diego-tijuana-border-teddy-cruz-fonna-forman/512222/

Náñez, Dianna M. “Tohono O'odham tribal members opposing Trump’s border wall take fight to McCain.” Arizona Republic. Published 23 Mars 2o17, accessed 12 May 2o17, http://www.azcentral.com/story/news/politics/border-issues/2017/03/23/tohono-oodham-trump-border-wall/99550594/ RE INDIGENOUS PROTESTS

Nguyen, Tina. “Trump’s base is flipping out about the border wall,” Vanity Fair, published 26 april 2o17, accessed 17 May 2o17, http://www.vanityfair.com/news/2017/04/trump-supporters-border-wall-funding

Pan-American Health Organization. “United States—Mexico Border Area.” Health in the Americas. Last updated 1o July 2o15, http://www.paho.org/salud-en-las-americas-2012/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=63%3Aunited-statesmexico-border-area&catid=21%3Acountry-chapters&Itemid=173&lang=en

Phillips, Amber. “History suggests Donald Trump’s big, beautiful, brick-and-mortar border wall may not be so outlandish.” Washington Post. Published 1 September 2o16, accessed 12 May 2o17, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/06/09/history-suggests-donald-trumps-big-beautiful-border-wall-may-not-be-so-outlandish/?utm_term=.96c0525c2b58

Rael, Ronald. “Borderwall as Architecture: The Divided States of North America.” In Borderwall as Architecture: A Manifesto for the U.S.-Mexico Boundary. Oakland; University of California Press, 2o17.

Rael, Ronald. “Introduction: The Revolving Door,” in Borderwall as Architecture: A Manifesto for the U.S.-Mexico Boundary. Oakland; University of California Press, 2o17.

Rodriquez Mega, Emiliano. “Mapping Mexico’s deadly drug war.” Science. Published 3o June 2o15, accessed 21 May 2o17, http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2015/06/mapping-mexicos-deadly-drug-war

Sacchetti, Maria. “Trump’s Budget Proves that U.S. Will Pay for Border Wall, Mexican Governor Says.” Washington Post. Published 18 Mars 2o17, accessed 3 May 2o17, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/social-issues/trumps-budget-proves-that-us-will-pay-for-border-wall-mexican-governor-says/2017/03/18/d991fb58-0c0a-11e7-93dc-00f9bdd74ed1_story.html?tid=a_inl&utm_term=.497a325d3213

Sheffield, Matthew, “Republicans in Congress don’t want the wall”: Democrats taunt Trump as he drops funding fight for his “big beautiful wall.” Salon, published 28 April 2o17, accessed 12 May 2o17, http://www.salon.com/2017/04/28/republicans-in-congress-do-not-want-the-wall-democrats-taunt-trump-as-he-drops-funding-fight-for-his-big-beautiful-wall/

Torrea, Judith. “Borderwall as Architecture [Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello].” Design and Violence. Museum of Modern Art [MoMA], published 19 November 2o14, accessed 11 May 2o17, http://designandviolence.moma.org/borderwall-as-architecture-ronald-rael-and-virginia-san-fratello/

Weizman, Eyal. “Introduction: Frontier Architecture.” In Hollow Lands: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation. New York; Verso, YEAR. 1-13

0 notes

Text

Neighbourhoods in the Air, Dragons Under the Road, Concrete Skies: Being a case study of 9 Dragons Interchange and Shanghai Tower

Shanghai is the biggest city, the single largest unit of urban life on earth. While its growth from fishing village to global hub spans over a thousand years, this essay will focus on the specificity of contemporary, post-reform Shanghai. For over a hundred years to from the mid-19th to mid-twentieth century, Shanghai was a unique global and modern city, a nod in the network of global exchange. For forty years after the Socialist revolution, Shanghai was subsequently unplugged from the outside world until in 199O the city returned to the global stage.

To the investigate the Reform Period of ‘Opening Up’ in Shanghai [199O—present] I have selected two artefacts from that time to situate in the greater social context of the city. The first case study is the crossing of the Yan’an and Chendgdu Bei Elevated Expressways in downtown Shanghai, nicknamed the Nine Dragons Interchange [fig.1], built in the mid 199Os. The second case study is the tallest building in China, Shanghai Tower [2OO8-2O14] [fig.2], located in the Pudong New Area district. These two case studies can be seen as bookends of the Reform Era, highlighting Shanghai’s re-emergence into the global flows. I begin by investigating the social context of Shanghai’s development as a city with a brief overview of the city’s history until the Reform Era arrived in Shanghai in 199O. I then perform two separate case studies on artefacts from this era of urbanization, grounding the artefacts in their specific social context to see what ideological programming they spatialize and embody. I investigate each object to probe the experiences of visuality at play and to see, as W.J.T. Mitchel has advanced, how “visual encounters with [these artefacts] inform the construction of social life.” I argue that the visibility of these objects make them ideologically invisible—rendering their underlying neoliberal political economy generally unquestioned. Both objects are part of a system of visibility which invokes traditional symbolism which obfuscates and naturalizes what the urban process is about.

To understand the urban process first requires looking at the history and growth of Shanghai, where from the 185Os to 1949 Shanghai’s history is interwoven with the history of modernity and globalization. Nine-hundred years after its founding as a fishing village on the Huangpu River, by the 185Os as a result of the “unequal treaties” following the Opium War the city had risen to China’s number one trading city, a unique treaty port where neither passport nor visa were required to enter and a site which can be viewed as a quasi-colonial occupation where concessions of land were forced into Euro-American control, to be run by business interests with extraterritorial immunity. The Euro-American traders “buil[t] a Western City that just happened to be in the Far East.” In this modernization, the city banks, gas lighting, electricity, telephones, automobiles and tramways, all appear on its territory for the first time between 1865 and 19O8, and over 1OO financial institutions were established in the part of the British concession along the river known as the Bund.

There also exists an idea that following the end of the Imperial period Shanghai experienced a “golden age,” staring in the 192Os. This is a discourse which reveals a few main narratives, one is the idea of Hai-Pai culture, where within China the city became synonymous with modernity. Literally meaning “sea receives hundreds of rivers,” Hai-Pai culture refers to Shanghai’s “close connection with the Western world, innate connection with market economy as well as innovative ideas, and thus has the most modern image among all Chinese cities.” In this first international incarnation the city develops “a local tradition of easy acceptance of outsiders,” which allows the city to “obtain a kind of sophistication with a strong merchant character. Commerce served as the primary motor of society.”

This golden age ended with the socialist revolution in 1949, when Shanghai was closed to the West and divested of internally, ending its first international era. In the years that followed Shanghai was converted to a “model state socialist city under the planned economy system and tightly supervised by the central government.” During the Communist period, the central powers decided that Shanghai must “play second city to Beijing.” Disinvestment during socialist times still had Shanghai providing about 25% on the GDP on average through the 197Os. As a result of Shanghai’s central importance to the economy, the central state powers were reluctant to implement reforms in Shanghai during the initial stages of the opening up, lest it go wrong and wreck the entire economy. During the first half of the Reform Era 1978 to 199O, Shanghai was viewed as the “elder brother” [lao-da-ge], a reference which had two important meanings: the conservation role and sacrifice of continuing on without reforms while the rest of the country opened-up; and “an expression that strong urged the city to take the lead in the new reform era.” The turning point was the establishment by the central government of the Pudong New Area, a free trade zone across the river from Shanghai, open to foreign investment and competition and administered by the city. The Pudong New Area was cleared of its 3OO,OOO inhabitants to make way for “new, quasi-private real estate developments,” the first in Shanghai in over 4O years. Since the 199Os, Shanghai has experienced a “rapid economic, social and spatial transition in the context of globalization… [and] re-established its prominent role at home and abroad.” The year 199O is pointed to as the year Shanghai began to take the lead, and marks Shanghai’s return to the global stage, and the city’s national and international symbolism is evident when paramount leader of China Deng Xiaoping described Shanghai’s new role as “Head of the Dragon.” Both case studies are from this period. To facilitate traffic flows within Shanghai and between the city and Pudong, a network of elevated highways was built in the mid 199Os, a component of which is investigated in case study no. 1. The second artefact is a recently completed supertall skyscraper in the heart of Pudong’s Central Business District, Lujiazui.

Shanghai��s first modernity was imposed on it from the outside, at the benefit of foreign concessions and Euro-American “Shanghailander” business interests. Never the less, Shanghai’s modernity was [at least] a two-edged sword, endowing the people of China with industrial urbanism, commercial knowledge and business acumen, and the prerequisites for Marxist revolution: unfair labour conditions for workers to unite against. Though the city’s first era of modernity was primarily for the benefit of foreign businessmen, unleashed from any ethical concerns besides profit, it is irrevocably tied to the end of the Imperial era and the history of both commodity capitalism and the Socialist Party in China.

But for whose benefit is Shanghai’s second period of international modernity? Who benefits from this accelerated period of massive growth and hypermodernity? The case studies which follow aim less to describe how the Reform Era transformations come to pass and instead probe why. Harvey explains that “productive consumption [and] investment in infrastructure,” as well as capital accumulation and compound growth are seen to be built into the state capitalist/ neoliberal Reform Era economy. Shanghai’s deliberate positioning as a global city supported by the visibility of its mediated image, but the visibility of the city obfuscates the ideological forces which requires or enable concepts like global cities to exist in the first place. These two case studies, in their aestheticizing of this ideologically motivated urbanization, can been to invisibilize their ideological underpinnings. By highlighting their visibility these artefacts obfuscate their materiality and the ‘why’ becomes invisible.

Case Study 1: Nine Dragons Interchange. The Chengdu Bei Lu and Yan’an Lu Elevated Expressways are reinforced concrete highways in central Shanghai crisscross and exchange traffic in a mid-air intersection known as the Nine Dragon Interchange [fig. 1]. Located at the apocryphal epicenter of Shanghai at the time of its construction, the interchange is the central junction of the city’s extensive elevated high speed road network. Built during the mid-199Os to service an increased circulation of traffic both within Shanghai and between the two sides of the Huangpu, the Nine Dragons Interchange connects the east-west flowing Yan’an Elevated Expressway with the north-south Chengdu Elevated Expressway with 12 options of direction changing interchange ramps, tendrils of concrete snaking through the air. These two central Elevated Expressways go on to connect with a network of city and state high speed roads running over major ground roads, a system which has its own dedicated traffic police. At night the underbelly of the interchange ramps bathed in a haunting azure neon glow of “rainbow-coloured light,” the Chinese translation of neon. The highly visible Nine Dragon Interchange has a global brand visibility, appearing even in the most recent James Bond movie [fig. 3]. In the mediation of 9 Dragons Interchange, traditional values have been blended into the infrastructure and made incredibly visible. Underneath the Nine Dragon Interchange is the Dragon Pillar [fig. 4]. The massive concrete column supports the interchange above, and is covered in a sculpture designed by Zhao Zhirong from the state art school, the ornamentation was intended to cover a vital and yet massive and unsightly column which is essential to supporting the interchange and flowing traffic above. The column, located between traffic flows on the city streets below, is not accessible by pedestrians. Only cars zipping by or idling in traffic approach the column, who lives a solitary life.

The motifs of dragon on the pillar refer to an urban legend during construction of the elevated expressways when—suddenly—construction halted when steel anchor columns for the concrete of the central pillar to come could not be pounded into the ground. No matter how much hydraulic pressure was applied, the steel would simply not sink into the ground. Construction was at a standstill, with engineers unable to explain why the anchors could not be laid, nor what was preventing the trouble. Meanwhile, a Fengshui theory spread among the construction workers: could it be that the pillar accidentally hit the “dragon vein” of Shanghai and offended the dragon guarding the city? ‘Dragon vein’ usually appears as long stretches of mountains and has a special place in Chinese common superstition. […] Dragon vein gives life to the country, and what is important is that, dragon vein can never be disturbed, or disasters may occur over night.

A traditional spiritual ceremony was held, an offering was made to the dragon sleeping below the center of Shanghai, and construction progressed. Once complete, the pillar was adorned with white and gold sculptural elements. People crossing under the Nine Dragons Interchange do so on an network of elevated pedestrian bridges, connecting the corners of the streets below and arcing over the traffic below and beneath the expressway above.

From these walkways, the white and gold column is illuminated with the sheen of countless headlights. At night the flat, grey underside of the purring concrete expressways above are bathed in blue neon lights. Blue is a symbol with its own traditional connotations of dragons, power, royalty and auspiciousness. The “rainbow-colour” glow of the neon also speaks to 192Os international Shanghai, and invokes Honk Kong, a city with a competitive or even antagonistic relationship to Shanghai, for the decrease of Shanghai in the 195Os was to the immense benefit of Hong Kong, and the emergence of Shanghai as the hub of investment into China in the 199OS bypasses the Hong Kong system and has led to the impression of Hong Kong as a “has-been” city, passed its prime.

Nine Dragons Interchange, in its apocryphal construction myth, ornate pillar, nickname and mediation combine to imbue the Reform Era neoliberal infrastructure in traditional practices. Looking at tradition as “an open document waiting for individual readings,” Wang explains that “the tradition document is a language system which has been produced in certain specific spoken environments and which continues to produce new meanings, new documents, and new traditions in other language contexts.” Here, the Nine Dragons Interchange itself can be viewed as a new tradition document, and a site where we can visualize ideological transformation of all of China through and the growth of its highway infrastructure system during the Reform Era. China went from a country having 19,OOO cars in 1985 to having 62,OOO,OOO cars in 2OO5. In the same time space a highway network of 64,OOO miles was unfurled across of all China, with its central node in the center of Shanghai, a mystical node of traditional and cultural power. In this way the highway is many things, pragmatic infrastructure and a multilayered document of tradition. While marvelling at its visuality, Harvey’s question of ‘why’ goes unanswered, and perhaps the is the point: The highway system is rooted in tradition where new privately owned cars on new system of infrastructure are anchored by dragonvein, and in so doing the ideological program of the highways are naturalized and invisiblized.

Case Study 2: Shanghai Tower Shanghai Tower [fig.2] is the tallest building in China and the second tallest building in the world at the time of this writing. Built for the Shanghai city government between 2OO8 and 2O14, Shanghai Tower can be seen as a late Reform Era victory lap for the city government, putting the finishing touches on their Pudong skyline, an authorial flourish nearly a kilometer in the sky. Shanghai Tower is a world of superlatives: the world’s fastest elevators which move at over 64km/hr or 18m a second, the world’s highest observation deck, and the world’s highest usable floorspace, the world’s highest hotel. Conceived in the Late Reform Era and built in only two years, “architectural representation of our contemporary world… massive in scale, disorienting in urban configuration, socially and economically stratified, and often overlaid with myriad media layers.” The 128-story supertall skyscraper is arranged around the vertical stacking of nine mixed-use residential/ commercial “neighbourhoods.” Each of the nine neighbourhoods in the sky has interior and exterior volumes: the interior core of the building contains the residences, while the exterior skin of the building envelopes the core. The spaces between the two buildings—one inside the other—are atriums up to 28 stories tall. These atria offer the unique “sky gardens” a twenty story atrium as a communal shared space and source of commercial purchases, services and social interactions, which also acts as an environmental barrier for the residences, the open air being more effective at keeping the building cool in the blistering Shanghai summers. There in an inherent visibility to constructing buildings as tall as Shanghai Tower, symbolic qualities which extend to perform ornamentation on the scale of the city of even the nation. The inherent visibility of something so large imbues it automatically with monumental and symbolic qualities, as does its sublime size. Its curving form dominating the Shanghai skyline, along with two other supertall skyscrapers [fig. 4]. The idea of having three central supertall buildings has been part of the plans for Pudong from the beginning. Shanghai Tower is the third and final of the Pudong skyline which towers over the Bund. A building this large and monumental in inherently a visual and symbolic project. As explained by Dan Winey of Gensler, the design of the building always took into great consideration: the importance of the building as a symbol for the re-emergence of Shanghai and China as major economic and cultural influences on the rest of the world. [… and] the Shanghai Towers’ relationship to the two adjacent buildings: the Jin Mao Tower and the Shanghai Financial Center. Shanghai tower is the last of the bunch, 4 supertalls would be inauspicious or even bad luck, maybe one day Pudong will have 5 supertalls, but the skyline is finished for now. Skyscrapers have historically been see as a “machine that makes the land pay” The twisting form of Shanghai Tower is a result of computer modeling to determine how to lessen the wind load on the building, and while more a result of pragmatic technocratic design is capped with a flourish of a shard of glass rising into the sky. Its twisting form decided by computer modeling to minimalize structural loads from typhoon winds, it is tempting to describe Shanghai Tower as emblematic of a “new type of National Form, a state capitalist style marked by arbitrariness, indulgence and extravagance.” But beyond Shanghai Tower’s technocratic aesthetics its designers—while never mentioning Hai-Pai style—essentially describe their building as an East-West fusion. As explained by Design Director and Shanghai native Jun Xia: Shanghai is, and for most of the twentieth century has been, a place where the East meets the West, … we envisioned Shanghai Tower’s design as a harmonization of the two cultures. While its verticality and methodology come from the West, its sky-gardens, spiraling form, the Yin-yang harmony of hardness and softness, etc. all come from the Chinese culture. Jun goes on to explain how: “In China how we talk about buildings’ inside and outside… there’s an inbetween. A grey space… there’s always an in-between space beside the outside boundary and the interior, family-function space. So I think that create that zone, that in-between space, is very Chinese. I was strongly convinced that this building, somehow from a spatial standpoint, reflects both future of technology, and universal mathematical language, but also has some kind of connotations of past of Chinese culture.”

Shanghai Tower as a blend of east and west, where it is Chineseness towering over the bund towering over every building on earth except for one. Shanghai Tower is an architectural ornament on the scale of the city of even the nation. However, the visibility of Shanghai Tower is not just a matter of its massive size or pre-eminence in the skyline, nor the interplay between the position of the sun and the building’s dual-skin, creating different transparencies—but an active process of hypermediation, where the skin of the building becomes a stage for visual events and a screen for the city below, the city across the river, and the cities across the world. From explosive Lunar New Year’s celebrations, to tourism events, international conference center, skywalking and a 6-star hotel, while projections along all 6OO+ meters of its height are envisioned soon. But again, traditional values in service of naturalizing state capitalist policy, a uniquely Chinese production of city space of Shanghai forever impact the urban imaginary and has expanded what’s possible when the outside of a building belongs to all the city’s peoples, even while the inside may be million-dollar residential units. Where the skin of a luxury hotel is considered valid public space.

Concrete in the Air But what have we learned about ‘why’ is investigating these artefacts? An elevated expressway interchange and an innovative and iconic skyscraper, both owned by the city of Shanghai and both figure prominently in the visualization and circulation of images of the city. Both of these objects live above the ground, suspended in the air, floating above the city, rivers of concrete carrying the city, islands of concrete, neighbourhoods of concrete, high in the sky. Concerning both artefacts’ materiality, the concrete of the highways and the concrete of supertall skyscrapers invoke what Adrian Forty has called the contradictory nature of concrete, that “[concrete] opens up possibilities, but at the same time closes off access to a previous way of life; and every concrete structure, in one way or another, announces this to us.” I have investigated how both case studies can be seen to represent a shift in usage of space in Shanghai, where their specific concrete forms are connected to networks within the country: of transportation, communication and networks of image circulation as well. Forty explains the liberating and destructive powers of concrete: What made concrete ‘modern’ was that while it has been liberating, it has at the same time been destructive. Its structural possibilities allow us to redirect our destiny, to build bridges and superhighways where none could be built before, to hold back the sea, the join continents, to build cities at densities which would previously have resulted only in unbearable squalor, to reverse or overcome the forces of nature so that mankind can live in greater comfort and security. In all these senses, concrete has been emancipatory. But the price paid for this is the loss of the old ways of life, of the craft skills of stonemasons, of workers in wood and metal. It cuts us off from nature, and eradicates nature… And as well as bringing us closer together, it cuts us off from one another—it is part of an irrevocable alteration of relationships between people. And these changes are permanent. With concrete, there is no going back. Its indestructability is both one of its most valued, and at the same time most reviled features. Nine Dragons Interchange and Shanghai Tower each go to lengths to re-attach themselves to premodern meaning In so doing, the modernity they embody is symbolically grounded in tradition. These sites are not just infrastructure, nor image-pillars on which the image of Shanghai is engineered and broadcast internationally, spatialized ideological nodes or the calcified ambitions of their era. They are not inert objects, but “quasi-objects” and “quasi-subjects,” active participants in the daily life of Shanghai. Within them is, perhaps, “crisis… embedded in the very structure of… capital accumulation.” To stimulate growth and fend of recession, and as the very heart of the state capitalist economy of China, Harvey argues that the nation’s economy is addicted to concrete and steel. Or rather, that construction is a way of dealing with “surplus capital accumulation by the technique of the spatial fix.” In their materiality, these two case studies spatialize the state capitalist design for the city. In their visuality, they obfuscate that spatialization and naturalize capitalist growth in traditional meaning. Megaprojecsts like Shanghai Tower represent the spatialization of the virtues of growth. The result, Harvey warns, is “not cities for people to live in… but cities for people to invest in.” The experience of these programmatic spaces, locations with function, have here been extended beyond their actual users to include the transnational communities of architecture and urbanism. Probing an understanding of Shanghai therefore allows us to understand its trajectory. With Shanghai as the global leader and torch bearer, the single largest unit of human life on it, it’s trajectory can be seen as the trajectory of the modern world itself.

0 notes

Text

REVIEW: Daniel Buren, L’Observatoire de la Lumière, Fondation Louis Vuitton. France. 2o16. 25 min. Dir. Gilles Coudert

Originally published on Cinetalk.net 3o mars 2o17

In this lush and tasteful half-hour investigation, ten-year ARTE veteran director Gilles Coudert aims his expert eye at French conceptual artist Daniel Buren’s year-long installation of coloured gels on the skin of the Frank Gehry-designed Fontation Louis Vuitton [FLV] in Paris. From May 2016 until April 2017 in a work entitled [in English] Observatory of Light, the twelve swooping and bending glass walls which form the “sails” of the FLV have been covered in a gridwork of colour and stripes, casting ever-changing colour combos on the terraces inside the shell of glass walls.

With standard ARTE production brilliance we are treated to sweeping helicopter shots, frantic Koyaanisqatsi-timelapses of coloured shadows moving across the heretofore white walls within the building.

And yet, in only 25 minutes and with no didactics, the selection of statements from the people involved seem to lay out the case against Buren’s work. The sweeping light and lines of the building are a matter of Gehry’s design, the colours Buren has had applied are only that: colours. The movement of the colour through the building is only possible due to Buren’s art riding on Gehry’s walls. Robert Rauschenbeg erased a De Kooning drawing and called it his own work in 1953 but at least gave it an honest title: Erased De Kooning Drawing. I suggest a far more truthful title for Buren’s work would have been Coloured-in Gehry Building, or if you prefer, L’Observatoire de Gehry en couleur.

Colour may be more colourful and pleasant than not-colour. Interviews with visitors to the building agree. However, most surprising and revealing are the brief moments Coudert decided to include: FLV decided to allow the artist to choose the colours, FLV says the colourful experience works better with their brand than the monochromatic gradients of diffused light and shadow, and most insidiously, FLV boasts how the building is for kids to enjoy themselves anyhow and kids like colourful things, they’re not as critical as adult art-lovers.

Reading between the lines, between glamorous helicopter camera swoops, Coudert allows the evidence to position the Buren work as a kid-pleasing, easy and light production of art-inspired participatory advertorial, reinforcing FLV’s brand and agenda. In a documentary that is very respectful to the work and which gives it a lavish visual treatment, it also presents a fascinating glimpse into the world of global luxury art, and is in both regards a wonderful film.

0 notes

Text

SPEAK! MULTIPLICITY TO POWER : Ali El-Darsa’s The Color Remains the Same and Culturally-Amorphous Planetarity

In a neighbourhood I helped gentrify, in a gallery whose location was not too distantly a warehouse of different types of wire tubing, in a small theatre room off the main space of Galerie Dazibao, in a rigid room rows of comfy red chairs face the glow of the cinema screen: fireworks sparkle and crackle in a nest of loading dock far below residential high-rises. Flickering footage of crowds. A squeaky cog, an old sick cassette deck. Soldiers in Martyr’s Square. “Let’s die in the explosion together, ha ha ha.” Apartment buildings and fractal patterns swirling in the miasma of video degradation. Crisp HD footage of university grads, an optimistic song of hope. A red circle, a peephole, a zone of transformation, a fragment.

And blackness; the void.

Behind the chairs a wall-mounted widescreen TV silently shows two versions of the same floating low-res cellphone video, a single headphone node guaranteeing a solo experience. On this rear screen El-Darsa and an unnamed woman navigate the urban reality of Beirut the day of a suicide bombing for six solid minutes, first without subtitles and once more with, looping.

Hovering between journalism and poetry, video and text, Ali El-Darsa’s The Color Remains the Same (2015) participates in the conjuring of a more contingent and amorphous cultural subjectivity, both in its subject—the artist—and the viewer. Physically and conceptually the bodies in the gallery “are put into conversation with fragments that generate… the possibility of perpetual re-encounter,” entering into a new dialogue upon each viewing. This work at first and even second glace generates a freely-decoded urban imaginary of a summer in Beirut, the day of a bombing. In its ambitions to inspire viewers to create their own open-ended meaning, the work is oblique, disorientating and kind of bland. There is tantalizingly little in the room with you, making your own position all the louder.

While the exhibition catalogue from Toronto alerts us to El-Darsa’s “own internalized compass” as a member of the Lebanese diaspora, this is a narrow position which offers the brand of expanded inclusiveness as just “yet another exercise in control from above, a marketing label of greatest benefit to the privileged.” Cultural-specificity perpetuates Imperial machinations of cultural separation, dividing to control. Linking the specificity of El-Darsa’s practice to his Lebanese-ness “perpetuat[es] cultural stereotypes and the ghettoization of already racialized minorities,” and does a disservice to the work.

In the work, El-Darsa shows his own shifting subjectivity within the events as the document unfolds, local to the events, vistior to the neighbourhood, member of the Lebanese diaspora, transient to the streets of Beirut. El-Darsa’s work reflects upon both his unprecise and fluid position within the events, memories, and cultural representations of event, up and including each and every loop in front of our eyes as audience and the loops to come tomorrow. Simultaneously member and outsider, visitor and local, El-Darsa presents a fluid and tangential self-narration to make the audience all the more aware of their own contingent placement in overlapping self-performative cultural circles. So instead of “explicitly manifests difference or that better satisfies the expectations of otherness held by neoexoticism,” El-Darsa’s work is aimed at the fracture points of continued colonial systems of privilege, a proposition of polyethnic plurality.

The space of exhibition is rendered an inwardly vast and subjective space allow us to question the normative circulation of power. The looping, subtitling and the interplay between the media reminds us not to discount our own ethnic position but to use it as one of—and just one of—the points on the grid of context.

A sphere has no West, only quadrants.

What resonates loudest in The Color Remains the Same is not any clear answers nor questions, but the unknowable and undecidable space between document and fantasy, film and text, in between cultures, where the lack of tangible answers is the answer itself, and the lack of a firm perspective perhaps the most productive perspective to have. What better to confront the dominant order than disorder, “the chaotic, demoniacal, Dionysian, emergent, shapeless, provisional, shape-shifting aspects of life.” More than the content of the videos it is the dialogue between the screens and the body which ask us to consider not only “the specificity of media at hand and their crucial part in creating networked, mediated memories and narratives,” but also whose narratives are they? And for what end? These are the kinds of undecidable questions generated by the work which brings me to claim it participates in “activat[ing] resistance against the dominant historiography’s ‘apparatus.’”

As curator and critic Gerardo Mosquera put it: “Power today strives not to confront diversity but to control it.” If we optimistically reroute Mosquera’s argument, could we say that the Greater Multiplicity of Diversities to control, the weaker Power gets? So if, as Cotter argues, culturally-specific exhibitions “reinforc[e] certain narrow and distorting views of ethnic identity that ‘diversity’ should have dispelled,” then culturally-amorphous work like El-Darsa’s can then dismantle or even obliterate those narrow and distorting views, cracking open the global psyche to a new polyfocal and righteous planetarity.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Focus: Perfection, Robert Mapplethorpe @ Montreal Musee de Beaux Arts - Gift Shop Review

Museum entrance fee: 20$ / 60$ for year-long membership

Set of 4 coffee cups: 200$

Set of 6 espresso cups: 300$

Non-Mapplethorpe vaguely bdsm-y basket, aprox. 36in diameter: 600$

Non-Mapplethorpe designer waste paper basket: 400$

Mauris dignissim nunc id ex cursus, id suscipit erat convallis. Curabitur lorem nisl, luctus non ligula non, pharetra gravida turpis. Donec vestibulum eu mauris id tincidunt. Proin urna tortor, facilisis suscipit congue in, varius id quam. Praesent eros orci, sodales et augue in, ullamcorper sagittis augue. Maecenas vitae luctus nulla, sit amet tempor lacus. Nulla nec pellentesque ex. Integer lacinia ligula ac faucibus tristique. Morbi volutpat, urna nec mattis euismod, est risus convallis ante, eget eleifend diam mi cursus ex. Cras convallis diam quis ultrices ultricies.

Curabitur risus felis, efficitur ut mauris at, tristique fermentum lectus. Nulla ornare neque ex, et commodo tellus volutpat ut. Mauris lacinia, magna at fermentum eleifend, sapien metus efficitur urna, non faucibus magna dui vitae arcu. Nulla tempus risus ut nisi molestie, nec rutrum odio sollicitudin. Integer eu diam.

0 notes

Text

Black Transparency by Metahaven - book review

Dutch collective Metahaven with a core of 2 who produce graphic design, speculative design, talks & texts since DATE. Starting with WHAT IN WHEN, Metahaven have begun working in film, video, and video installation work. Central to their oeuvre in all media is the theory espoused by Dieter Lesage in his 2005 essay “Empire and Design” that all that is real in the world is a matter of design. Their first book, Uncorporate Identity (YEAR, Lars Muller) covers their output YEAR to YEAR and their projects involving branding the anomalous Sealand “nation,” basically a squatted, derelict offshore radar installation. Alongside co-editor Vishmidt, Metahaven declare “MONEY QUOTE”. Wrap that up with a bow HERE.

This fresh new unit Black Transparency is a collection of essays from YEAR to YEAR. Unlike their 15min film of the same title (which is fictional agit-prop with a dreamy verisimilitude and uncanny something yadda) the text investigates the nature of unwanted or “black” transparency in the flow of state and corporate secrets as invisible imperial machinations etc.

The essays here are direct, academic accounts of various phenomena under the Metahaven gaze: the production of Russian fake-viral web content as a political tool, something something Ukraine, the search for Wikileak’s logo designer and the tale of their own designs for real or speculative clients. These essays are awesome SAY WWHY.

Black Transparency is published by Sternberg Press (€22.00.)

0 notes

Text

Justin McGuirk, Radical Cities

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Donec mattis risus erat, eu commodo elit placerat ac. Nullam in porttitor urna. In hac habitasse platea dictumst. Quisque metus lorem, blandit vitae iaculis id, tincidunt eget libero. Pellentesque habitant morbi tristique senectus et netus et malesuada fames ac turpis egestas. Sed accumsan, orci eu varius maximus, ligula nibh tempor quam, in egestas diam neque et massa. Morbi varius eu libero aliquam bibendum. Nam nisl orci, placerat aliquam efficitur sed, volutpat iaculis nisi. In suscipit ut libero eget auctor. Fusce venenatis rutrum sem ac tristique. Sed ut scelerisque lacus. Quisque leo diam, mattis vitae cursus sit amet, tempus at lectus. Maecenas molestie, erat eu volutpat dictum, turpis elit posuere risus, euismod molestie est risus id sapien. Morbi sed lacinia lorem, eu dignissim felis. Cras id bibendum quam, vitae faucibus ligula. Maecenas non finibus ante. Vestibulum tempus aliquam libero. Maecenas non arcu sed erat tempor mattis a eget eros. Etiam et enim nec ligula suscipit ultrices. Aenean aliquam, lectus id consectetur finibus, nibh purus dignissim nunc, a consequat tortor massa nec magna. Nullam ipsum purus, placerat sed consectetur eu, pellentesque vel est. In hac habitasse platea dictumst. Praesent auctor ut justo nec pulvinar. Nullam eget sodales elit, ut condimentum odio. Sed fermentum consectetur sem quis egestas. In ac velit odio. Pellentesque tristique ultricies ligula, eu cursus ipsum commodo eu. In nulla diam, luctus et ante id, tristique scelerisque nulla. Duis bibendum justo et pellentesque viverra. Praesent vitae leo bibendum, tempor metus a, elementum ligula. Maecenas posuere enim ac est mollis hendrerit. Praesent lacinia nunc in quam placerat, eu consectetur massa lobortis. Etiam fringilla rutrum dignissim. Donec porttitor justo ac ullamcorper venenatis. Etiam sem urna, venenatis ut sapien et, placerat fringilla leo. Nullam quis nisi ullamcorper, tempor risus fermentum, accumsan justo. Pellentesque faucibus gravida tellus. Phasellus diam tortor, faucibus a mattis euismod, tincidunt eget orci.

0 notes

Text

BK RVW:: Undocumented: The Architecture of Migrant Detention by Tings Chak

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Donec mattis risus erat, eu commodo elit placerat ac. Nullam in porttitor urna. In hac habitasse platea dictumst. Quisque metus lorem, blandit vitae iaculis id, tincidunt eget libero. Pellentesque habitant morbi tristique senectus et netus et malesuada fames ac turpis egestas. Sed accumsan, orci eu varius maximus, ligula nibh tempor quam, in egestas diam neque et massa. Morbi varius eu libero aliquam bibendum. Nam nisl orci, placerat aliquam efficitur sed, volutpat iaculis nisi. In suscipit ut libero eget auctor. Fusce venenatis rutrum sem ac tristique. Sed ut scelerisque lacus. Quisque leo diam, mattis vitae cursus sit amet, tempus at lectus. Maecenas molestie, erat eu volutpat dictum, turpis elit posuere risus, euismod molestie est risus id sapien. Morbi sed lacinia lorem, eu dignissim felis. Cras id bibendum quam, vitae faucibus ligula. Maecenas non finibus ante. Vestibulum tempus aliquam libero. Maecenas non arcu sed erat tempor mattis a eget eros. Etiam et enim nec ligula suscipit ultrices. Aenean aliquam, lectus id consectetur finibus, nibh purus dignissim nunc, a consequat tortor massa nec magna. Nullam ipsum purus, placerat sed consectetur eu, pellentesque vel est. In hac habitasse platea dictumst. Praesent auctor ut justo nec pulvinar. Nullam eget sodales elit, ut condimentum odio. Sed fermentum consectetur sem quis egestas. In ac velit odio. Pellentesque tristique ultricies ligula, eu cursus ipsum commodo eu. In nulla diam, luctus et ante id, tristique scelerisque nulla. Duis bibendum justo et pellentesque viverra. Praesent vitae leo bibendum, tempor metus a, elementum ligula. Maecenas posuere enim ac est mollis hendrerit. Praesent lacinia nunc in quam placerat, eu consectetur massa lobortis. Etiam fringilla rutrum dignissim. Donec porttitor justo ac ullamcorper venenatis. Etiam sem urna, venenatis ut sapien et, placerat fringilla leo. Nullam quis nisi ullamcorper, tempor risus fermentum, accumsan justo. Pellentesque faucibus gravida tellus. Phasellus diam tortor, faucibus a mattis euismod, tincidunt eget orci.

0 notes

Text

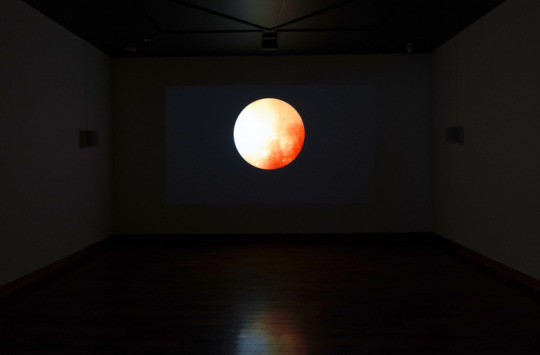

XRAY, Lost Paradise @ Station 16 Gallery

XRAY, Lost Paradise (installation view), Station 16 Gallery, 2016. Photo credit Amanda Brownridge, available from Station 16 Gallery.

0 notes

Text

You Can’t Be a Palm Tree in Copenhagen: and other postcolonial thoughts about Superkilen

Originally published in CUJAH, 2o17.

Superkilen is a 322,000 sq. ft. / 33,000 sq. m urban space in the Copenhagen neighborhood of Nørrebro, described by Danish starchitects Bjarke Ingels Group as “the toughest hood in town.” Commissioned by philanthropic organization Realdania in partnership with the city of Copenhagen, Superkilen spans a length of 750m comprised of three zones of mixed public programmes: The Red Square with a program of outdoor fitness, sports and benches; The Black Market which functions as a conventional town square with fountain, trees and benches; and The Green Zone which is designated for sports and play, consisting of a few grassy hills and outdoor sports facilities. The length of the park is crossed by bike paths which extend off into the rest of Copenhagen. Installed throughout the urban park are 108 fixtures from around the world, branded as “a world exhibition of furniture and everyday objects.” Superkilen formed part of a larger renewal project in the area, combining four different public spaces at the cost of 58.5 million DKK. The designers stated that they wished to give something to the area which the residents could be “proud” of, a “surrealist collection of global urban diversity that… reflects the true nature of the local neighborhood.” Its program unfolds in a local climate of political and social tension. It has been demonstrated in an exhaustive analysis by Brett Bloom that the design and implementation was completed without meaningful participation or feedback from the community, who envisioned a park with trees and grass and instead received concrete painted green, slippery when wet.

Officially unveiled in 2012, Superkilen remains unfinished—“perhaps will never be finished”—and is in need of constant repair. Rather than a true polyfocal, pluralistic space of conviviality and hybridity, Superkilen and its sponsors aims to wield the brand of multiculturalism to integrate the current and future residents of Nørrebro into the mainstream agenda. Superkilen can also be seen “as a public way for the status quo power structure to process demographic shifts through a charade of multiculturalism.” Bloom argues it spatializes neo-liberal values and aims to intervene in the formation of individual and collective subjectivities in the neighbourhood’s residents. Adopting the viewpoint of Gerardo Mosquera, this paper will argue that through a mix of banal, transparent, ornamental tokenism the ultimate program of this funky yet ideologically charged public space renewal project “[strives] not to confront diversity but to control it.”

Superkilen is the initiative of Danish philanthropic organization Realdania. Publically committed to “projects in the built environment: cities, buildings, and the built heritage,” Realdania receives its philanthropic funds from the profits generated by real estate holdings and investments. It has been argued that it is “essentially a financial investment company.” The organization has enormous power in Danish public life, described as a “parallel structure” to the Danish government in terms of influence on what gets built in the country. Realdania approached the city of Copenhagen with the idea of the alien Superkilen appearing and reorienting the civics and subjectivities of the neighborhood: Realdania came to Københavns Kommune [The City of Copenhagen] and said, ‘We want to do an experiment. We want to see if we can change the social behavior or standard, the perception of the area by making a new city room.’ To us it was a bit like a UFO landing because it was a top-down approach. Nørrebro is renowned as a hotbed of leftist activism and a growing hub of non-Western migration from Muslim-majority countries. The accompanying map [fig. 1] charts some of the history of the neighbourhood.

After the founding of anarchist squatter city Free Town Christiania on a former military base across town in the Copenhagen harbour, in the 1980s and 1990s Nørrebro was a bastion of political agitation for autonomous communities. Nørrebro was the major site of buildings squatted by the BZ movement, who occupied multiple buildings at various times between 1981 and 1995. Various pro-autonomy, anti-police, anti-EU, alter-globalization demonstrations (including even a party-style Reclaim the Streets event) erupted into full-scale rioting across Nørrebro and the bordering communities at least five times in 25 years, with countless other skirmishes between radicals and the state. At the same time, Nørrebro was the location of a major concentration of non-Western migrants in Copenhagen the bulk of asylum seekers arriving in the 1980s from Iran, Iraq, and the Occupied Territories and in the 1990s from Somalia and Bosnia. In Denmark, it is illegal to register religious affiliation, but it is estimated there are some 170,000-200,000 Muslims in Denmark, about 3.7% of the total population.

In a span of six months both of these local communities—squatters and Sufis, anarchists and aniconists, intellectuals, agitators, adolescents, grandparents—erupted into the streets in the form of unrelated international campaigns of media-aware networking, demonstrations, protests, public pressure, international lobbying and smoldering riots. In January through the summer of 2006 Muslim-majority governments and Islamic diasporas became enraged by what was perceived as blasphemous cartoons published in Copenhagen the previous year by the far-right newspaper Jyllands-Posten. Unleashed by savvy networking of the Danish Muslim community leaders, the rage around the world at the cartoons—often paired with local grievances—resulted in worldwide protests and attacks on the Danish embassies in Lebanon and Syria, resulting in 200 deaths around the world. In December of the same year the youth/squatter/activist/ leftist/punk element raged at the demolition of Unhlushuset—Nørrebro’s center of leftist activism and punk concerts since it was initially occupied in 1984—resulting in rioting in December 2006 and March 2007 [fig. 2]. Seven months after the general rioting ended, BIG’s winning Superkilen project was submitted for the initiative to redevelop a 750m stretch of urban corridor in Nørrebro just down the street from the former site of Unhlushuset, now an empty lot. To this fractured environment, to a district rife with insurgent energies, what could be nicer than a pleasant stroll through a “modern romantic garden”?

Regardless of official Superkilen marketing texts which present itself as a benevolent and positive force, the core program of the park is the integration of Nørrebro residents into controllable behavior. Bjarke Ingels is open about this in the official Superkilen monograph: “This project was all about integration: it was like six months after the riots, after the Mohammed cartoon crisis. It was so present in this neighbourhood, and people in Denmark were suffering a bit from the ambiguity of being tolerant.” BIG’s own tolerance can be questioned, describing Nørrebro as “a potent mixture of frustrated youth culture and maladapted immigrants.” And a tolerance contingent on the maladapted intruders first adopting mainstream so-called “Danish” values. In the tightly controlled appearance of the physical space of the park and the curation of exotic yet banal objects, individual and collective subjectivities are molded. Superkilen “[orchestrates] social behavior by providing scripts for encounters and assembly… by reinforcing relatively stable cues about correct behavior.” As described by Brett Bloom: When you spend time in Superkilen, you are not simply enjoying a public park when you stroll, play a game of chess, or watch your children frolic, you are ‘being creative’ and you are ‘being integrated.’ You are participating, (extremely) in a magic machine for producing individual and collective subjectivities. Superkilen’s is a token tolerance, something to ease the ambiguity of tolerance—a monument to tolerance, which could embody tolerance and thereby alleviate the Danes of that responsibility. Its collection of park items are generally those which “explicitly manifests difference or that better satisfies the expectations of otherness held by neo-exoticism,” Superkilen is replete with an Orientalizing gaze which aims to control the Other by controlling its representation in the neighbourhood, in the press, and within popular consciousness. The Afghan swing has been modified “you can’t go as high in Copenhagen as you can in Kabul,” the Jordanian bus stop sign from the land where “buses never come on time,” some soil from Palestine, uninspiring Cold-War era sculptural plop from Kazakhstan. Even the colours of the Superkilen promotional materials and the park themselves can be a space of activating subjectivities through iconography, ornamentation, and the powerful associations of colour, as seen in [fig. 3]. Superkilen “wants to take credit for pointing out diversity and equate this recognition with supporting it, [the park] and its enablers are paternalistic about democracy, difference, and making city spaces.” The paternalistic microcosm of power relations between Superkilen’s creators and end-users can also be seen on the scale of the continent: Seen as a threat to social cohesion… or to the secular character of European societies… adherence to Islam or declaration of some sort of Muslim identity by Muslims in Europe has come to be viewed as a deficiency, as something that had to be rectified through adaptation to European cultures or to be contained through various forms of exclusion. Featuring prominently in the process of construction of societal insecurity in most European societies, Islam, and more specifically, Europe’s Muslims, have unavoidably borne the brunt of public scrutiny and condemnation. Superkilen’s objective of integrating the maladapted is demonstrative of what Gerardo Mosquera dubbed Marco Polo Syndrome, “[perceiving] whatever is different as the carrier of life-threatening viruses rather than nutritional elements.” There exists a body of academic text describing Denmark as “one of the most staunchly anti-Muslim nations in the west,” just as there exists a smaller, weaker body of academic work (and right-wing popular press) defending “Danish values” and “Danish humour” and criticizing the first critique’s methodology. Thus we can see how this form of cultural xenophobia is a “complex disease that often disguises its symptoms.” The multicultural integration that Superkilen strives for is not an enlightened, postcolonial “new consciousness” but more of “a tolerance based on paternalism, quotas and political correctness.” Rather than an earnest attempt at a multicultural public space or meaningful participatory creation of the park, Superkilen is seen as “a monument to globalization, petroleum, and neoliberal city making [neither] ecologically, socially or environmentally, appropriate to its climate.” Towards these quotas, espousing the accepted and expected rhetoric of human rights and diversity Superkilen responds with empty gestures.

Superkilen is a space which attempts to make capitalism more beautiful while still being purposely ugly enough to avoid accelerating gentrification too much. To paraphrase Vito Acconci, Superkilen belongs to the people and they, in turn, belong to the state, (and perhaps the state belongs to Realdania). As Antoine Picon explains, “to be believable, respected and operative at moments other than those marked by the exercise of sheer force, authority has to be adorned.” The politics of Superkilen can be seen as the articulation of systems of signs and power—the signs of token multiculturalism, urban ornamentation and renewal. Here the ornamentation serves as a reminder of the state’s power to intervene in the urban landscape, and globalization’s ability to “impose homogenized, cosmopolitan cultural patterns built on Eurocentric foundations, which inevitably flatten, reify, and manipulate culture differences.” The subjectivities Superkilen desires for its users replicate and continue the power relationships which programmed their subjectivities in the first place.

Superkilen is a street battle where the postcolonial melancholia of Denmark faces off against the double consciousness of Nørrebro residents. The concept of “double consciousness” refers to an individual’s awareness of both the functioning of idealized roles and their simultaneous exclusion from those systems, “a concept in social philosophy referring, originally, to a source of inward “twoness” putatively experienced by African-Americans because of their racialized oppression and disvaluation in a white-dominated society.” The idea of “postcolonial melancholia” stems from former colonial powers’ malaise in the face of ethic plurality in their own formerly homogenous societies, or as Gilroy explains: “[the] inability to mourn its loss of empire and accommodate the empire’s consequences… the elemental challenge represented by the social, cultural and political transition in which the presence of postcolonial and other sanctuary seeking people has been unwittingly bound up.” Critics point to BIG and Realdania’s selection of trees: non-native species of flora which aren’t appropriate for Danish ecology, glowing red reflections bouncing into adjacent homes, broken and fading furniture, unforeseen expensive repairs, sound system unwanted and unplugged, a folded concrete canopy which was never installed, near-instant graffiti removal while real Nørrebro outside the confines of the park is left to be scrawled upon endlessly … But what if this series of inappropriate selections stem not from a stubborn, paternalistic indifference or a busy starchitect oversight diet of missed details, but rather emanates from a calculating, politically savvy and theory-based gesture specifically aimed at engaging the double consciousness of Nørrebro migrants and their descendants?