Text

I'm going to continue to scream this: THT is not a story about motherhood and the handmaids. And it never was.

It’s wild to me how many people, critics, viewers, EM, and the writers themselves, seem to fundamentally miss what Margaret Atwood was actually saying. I keep seeing takes like “the show is more hopeful” or “this was really about June finding peace as a mother,” and I just want to scream: No. That’s not the point.

This was always a story about June. About resistance. About breaking free. About a woman reclaiming her autonomy, her voice, her desire, her power, in a world designed to strip it from her. And yet the show’s finale, and commentary like this article, keeps shrinking that down to something far more palatable: motherhood as salvation, forgiveness as closure, “hope” as settling down and keeping quiet.

And that’s not just a misread. That’s a complete dismissal and lack of understanding of the original feminist message Atwood was making.

Atwood was tearing the box down. The box that tells women we only matter if we are nurturing, self-sacrificing, morally pure. The show, by the end, reinforced that box. And June, a character who once raged and fought and wanted, ends up passive, selfish, hypocritical, emotionally dishonest, and caged by the very ideals she once defied. She’s lying to herself, to Luke, to Nick (when she lets him go without a word), and to the audience. And the show just lets her.

I don’t feel empowered watching her walk into the ruins of the Waterford house. I feel pity. Because June clearly feels something she’s too afraid to act on, too afraid to name, and that is not the kind of “hope” I’m interested in.

And here’s where it gets even darker. Look at the kind of ideology this ending mirrors. Remember that Butker graduation speech last year? Where the Kansas City Chiefs kicker told a room full of women that their real purpose was to be wives and mothers? That his wife’s life only truly began when she embraced her vocation at home?

The backlash to that speech was massive, and rightfully so. But how is it any different from the message The Handmaid’s Tale sends in its final hours? That June’s path to peace is through motherhood. That survival and trauma and passion and rebellion are secondary to being someone’s mom again. That desire, love, wanting, especially the kind she had with Nick, must be set aside for a softer, safer, quieter life.

And I’m sorry, but that is not feminist. That is not liberation. That’s putting June back into a different kind of Gilead.

And that’s what makes the show’s ending so frustrating because we know what a real ending could look like. One that honors June’s autonomy, her fire, and her right to choose a life on her terms. Not because she’s a mother. Not because she’s redeemed. But because she’s free.

There’s this fanfic I adore — one that actually understands the heart of Atwood’s message — and I want to end with their words because it says everything the show failed to:

“You’re crazy,” Moira told her as Nick, Beth and their guide carried on down the path. “You’ve got a chance to get out, come to Canada, and you’re throwing it away. Again. For what? For him?” June shook her head. “It’s not for Nick, it’s for all of us. We can be a family there, be who we want to be, no pressure or expectations. Remember my mom? How she used to tell me I was too conventional? That I didn’t need to do what the world expected of me, I should live life on my own terms. Well, that’s what I’m doing now. You should see it up there, Moira. It’s beautiful, and open, and free. And the people are good people. They look out for each other. They help others escape Gilead or support them to go back and fight. You should come too – you could do so much good there.”

This is it. This is what the show should have fought for. A June who chooses herself, who chooses freedom, not safety, not a boxed-in version of motherhood, not someone else's definition of healing or closure. A June who remembers her mother’s voice and lives beyond the narrative she was forced into. This ending had me in tears.

That’s the ending we deserved. And the one that Atwood, I believe, would have respected far more.

The show could have ended with June choosing truth. With her being raw, messy, honest. With her rejecting the lie that motherhood alone redeems her. Instead, it gave us a hollow ending that props up the very systems Atwood set out to burn down.

So no, this isn’t more hopeful. It’s just more familiar. More comfortable for people who are still afraid of women who want. And if the audience, the writers, and the press can’t see that, maybe it’s because they’re still living inside the box too.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

“My name is Nick Blaine, I’m from Michigan.”

Religious extremism and indoctrination, a character analysis:

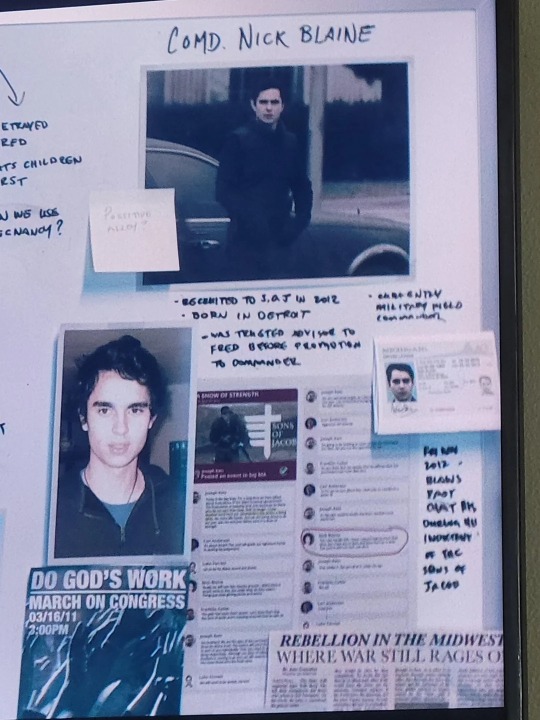

I found this picture on Reddit. In this episode, the camera shows each section of Mark’s whiteboard very briefly: there’s one on Fred, one on Serena and one on Nick. Only Nick’s says “possible ally?”, and it gives some insight on his involvement with Gilead, if you can read the shitty handwriting.

I would do ANYTHING to be able to read Nick’s comment on that FB post, because no matter what it was, Tuello saw it, and still saw Nick as a potential ally and still calls him “an honorable man”.

There’s also a March On Congress poster from 2011, what’s Nick’s involvement with that? It was clearly a religious march, possible early signs of Gilead’s propaganda.

There’s also a news article “Rebellion in the Midwest”, where Michigan is. Did Nick lose his brother and father then? I wish we could tell the date of when the article came out.

But what I want you guys to pay attention to, is the logo in that Sons of Jacob poster. A cross with 4 bars to the left.

Now look at the symbol below, on the window of the job center “A worthy path” where Nick had an interview with Pryce. It’s clearly a deviation from the cross in the Sons of Jacob poster, with a candle and its flame in the middle of the extended hand. In the Bible, candles represent light, guidance and the presence of God.

You see the symbols’ resemblance, right?

When you think of the founding members of SOJ, we have Waterford, Guthrie, Pryce and then Lawrence as the economist. It’s safe to say Pryce was a mastermind manipulator, using young men’s weaknesses to get them to pledge allegiance to Gilead, and my head canon is that he built THE system to entrap men like Nick into serving Gilead. Just like Guthrie built the Handmaid’s system and Lawrence founded the colonies.

During their meeting, Nick told Pryce about his brother, and his dad. He gave Pryce a window into his life and Pryce saw the desperation, the sadness, the wit even, to make an ideal puppet out of Nick. He knew just how to get him: “maybe there will be a job in there for you.”

It’s predatory, and when you take in the religious motive and symbolism, it makes it all seem like a masterfully crafted plan, because it is.

So Nick got involved, recruited even. The general consensus was that he was 19 in 2012. Do you know how incredibly stupid my brother was at 19? How gullible and influençable?

I know. Because at 19, my brother went to pray at the local temple ONCE, and came back a different person. He came home and demanded I, his 13 year old little sister, covered my hair, started praying, stopped listening to music or I’d go to hell.

My mother intervened and talked sense into him, but I have been around enough young, lost men without a father figure to see them fall into the traps of religious extremism. Cousins I grew up playing soccer with would not be in the same room as me if my hair was uncovered, or would refuse to talk to any woman that was not their mother or sister.

This is another way the show failed in my eyes, because Margaret Atwood herself said that no one but the men at the top is safe from Gilead. No one but the Sons of Jacob themselves, is safe.

There was a perfect opportunity at exploring the endoctrinement of the young men who fell into the traps of Gilead.

Just one Nick or Isaac centered episode could have given more insight, more substance to how men became tools for the system.

They could have mirrored it by showing the consequences of not adhering to the system, the consequences of not complying. They could have showed what was at stake before and how so many men were now the driving force that tortured women and ripped their children away from them. How they felt, what they believed in.

What were they planning to do with Luke, after shooting him then putting him at the back of an ambulance after being captured in the forest? Were they going to try and make him a guardian? What happened to the men who got captured but who were not willing to comply? What ties did the guards and drivers have to their commanders? Were they contracts signed, allegiances pledged, blood pacts drawn?

I know it’s The Handmaid’s Tale, and ultimately we have the tale of June as the main protagonist, but the message of this book and this show could have been so much more impactful had they developed some of these storylines, especially Nick’s.

I had the wrong assumption that Nick was a red pilled incel who got roped into an evil machine, but that does not actually fit his character. Incels have a deeply rooted hatred for women, and Nick does not have an ounce of misogyny in him.

I believe Nick was aware of the machine crushing down the country and weighed his chances. What real choice did he have? What would happen if he decided not to attend those meetings, not to drive those commanders? Would putting his head down and keeping his mouth shut be enough to survive and keep his family alive?

Nick Blaine is one of the most misunderstood characters in The Handmaid’s Tale, but one held at the highest standard. He is a survivalist, with no real allegiance to anyone or anything but the people he truly loves: June and Holly. He was used by everyone he encountered: Pryce, Fred, Serena, June, Tuello, Lawrence, even Rita. Not a single person asked him what he wanted out of this, what he wished for, what he needed.

He was a simple pawn, in an evil game of chess, steered in any direction, as long as it benefited the player.

So June let him get on that plane, because he was her last piece to use, and she had to, needed to win. He was collateral damage to her, and she was everything he’s ever wanted.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Love and Humanity and THT

I’ve been re-reading one of my favorite books lately, Bittersweet by Susan Cain, and many passages have struck me in new ways since the end of The Handmaid’s Tale. They have brought me some comfort and understanding, and I want to share a few of those thoughts here.

First, a small disclaimer: I approach life, and stories, with a worldview rooted in love. I believe love is at the core of who we are as humans. I recognize that worldview is not shared by everyone, and I don’t expect all media I consume to reflect it. But I read both THT and TT books first, and I saw love as an central theme of Margaret Atwood’s message. Love is what kept Offred alive in a world designed to dehumanize her. Her love for Luke, her daughter, and Moira lived on through memory. It reminded her she was still a person. Her growing love for Nick emboldened her, just as his love for her strengthened him. From the historical notes, we understand that Nick ultimately risks everything to help her escape Gilead, out of love for her and their child.

So yeah, excuse me for expecting the TV adaptation to honor that.

There are so many reasons I loved this show: the character development, the world building, the provocative and thoughtful messages, THE SUBTEXT, the acting, etc., etc… In Bittersweet, Cain shares a comment someone once made to her:

My affinity for serious movies and thought-provoking novels is all an attempt to recreate the beauty of my life’s most honest moments.

That resonated deeply with me. It’s part of why Nick Blaine became my favorite character. Not necessarily because I shipped him with June (in fact, I didn’t really care if they stayed together in the end), but because Nick became the most honest and real character to me. June started that way, too, but over time she became more myth than person. And while superhero characters have their place, I thought this show was doing something different, something that felt so true to humanity.

I’ve also been frustrated by the way some fans, and even some creators, state that love is not the point of the story. (Aunt Lydia also said that, but what do I know?) I’ll admit, I used to look down on romantic narratives, thinking they were somehow less “serious.” But I’ve learned and am changing. Cain writes:

Another view has existed for centuries, one that we rarely hear. It suggests that our longing for “perfect” love is normal and desirable; that the wish to merge with a beloved of the soul is the deepest desire of the human heart; that longing is the road to belonging. And it’s not just about romantic love… And, therefore, the proper attitude toward [stories of romantic love] is not to dismiss them as sentimental nonsense, but to see them for what they really are: equal to, no different from, the music, the waterfall, and the prayer. Longing itself is a creative and spiritual state.

Cain’s chapter on love and longing is interwoven with reflections from various spiritual traditions, including Sufi mysticism. One quote in particular has stayed with me in this context:

Like everything that is created, love has a dual nature, positive and negative, masculine and feminine. The masculine side of love is ‘I love you.’ Love’s feminine quality is ‘I am waiting for you; I am longing for you.’ … Because our culture has for so long rejected the feminine, we have lost touch with the potency of longing. Many people feel this pain of the heart and do not know its value; they do not know that it is their innermost connection to love. —LVL, Sufi mystic

While this quote uses binary language, I don’t take it as a literal or rigid framework about gender or energy. (Personally, I don’t believe in universal binaries in that way.) But I do think the quote speaks to something real: that quieter and more yearning forms of love are undervalued in a world that prizes action, dominance, and certainty. That other kind of love is often associated with women or “feminine” traits, and it’s frequently dismissed. So when a show like The Handmaid’s Tale, which has seemingly centered women’s voices, mocks the audience that values these emotional truths, it feels like a betrayal of its own message.

So where do we go from here, now that the love and connection we longed for is gone?

I’ll leave you with one final quote from the book. A reminder that what we saw in this show and in these characters was something bigger than just what was on screen. You don't need to be ashamed of it or regret it. This is a reminder to take those experiences and feelings and find meaning in them, and to be cautious about where we place our faith in the future:

Our commonest expedient, is to call [the longing] beauty and behave as if that had settled the matter… But the books or the music in which we thought the beauty was located will betray us if we trust to them; it was not in them, it only came through them, and what came through them was longing. These things—the beauty, the memory of our own past—are good images of what we really desire; but if they are mistaken for the thing itself they turn into dumb idols breaking the hearts of their worshippers. For they are not the thing itself; they are only the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have not heard, news from a country we have not visited. —C.S. Lewis

#osblaine#nick blaine#since I have no irl friends who watch this show#i won't shut up about it online!#bittersweet susan cain

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"It has been a real pleasure for me to, um, to watch you grow or whatever the fuck, in there." "You do not have to say that." "I mean it, Syd. Watching you step up, you know? I mean, I cannot imagine how hard that must be with my fucking nephew, walking around like a fuckhead. I mean, you are a hardworking motherfucking professional. And you're good to everyone, you know..."

693 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE BEAR 1.02 / 4.10

940 notes

·

View notes

Text

VIPs? Yeah, a family from Los Angeles. The parents are social workers. And their daughter’s been cancer-free for about six months now….She did mention that her daughter’s always wanted to see snow in Chicago. I wish we could afford to bring them back in December.

You know what we can afford? Sammy’s power washer, ten-pound bag of sand, and a 45-degree angle nozzle. Thank you, fucking DeVry.

288 notes

·

View notes

Text

This would have been amazing in the finale!! So much more closure. But they wouldn’t want us to remember Serena abusing June or Nick loving and helping her since it would undermine their fragile redemption/villain arcs😭

This montage is incredible!! it made me emotional. If something like this had been added in the final episode, it would have been so much better.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Redemption and THT

I’ve been re-reading portions of the original The Handmaid’s Tale novel, and I was quite struck by this passage in chapter 24. Offred is remembering a documentary her mother had her watch as a child about a woman “who had been the mistress of a man who had supervised one of the camps where they put the Jews.”

This portion of the book is so striking and profound. It explores the themes of human complexity for good and evil and the banality of evil. This is an important message.

If this is what the season 6 writers/showrunners were going for, I recognize the attempt. The execution and follow through, however, were half-baked and illogical. Margaret Atwood accomplished in less than 2 pages what the show’s writers took a whole season to try to do.

Again, this message is an important one, but it absolutely does NOT work for Nick Blaine. And using his character to push this message, in fact sends a very different one: that people manipulated by and caught up in systems beyond their power, who detest the power they’re given, who find ways to safely and effectively enact change, etc., these people should be viewed as irredeemable lost causes who will always ultimately choose evil. How does that help us create a better and united society? So why does this narrative seem so backwards on Nick’s character?

To emphasize my point, I want to share another quote about the utility of suffering:

“What do we do with suffering? As far as I can see, we have two choices—we either transform our suffering into something else, or we hold on to it, and eventually pass it on.

In order to transform our pain, we must acknowledge that all people suffer. By understanding that suffering is the universal unifying force, we can see people more compassionately, and this goes some way toward helping us forgive the world and ourselves. By acting compassionately we reduce the world’s net suffering, and defiantly rehabilitate the world. It is an alchemical act that transforms pain into beauty. This is good. This is beautiful.

To not transform our suffering and instead transmit our pain to others, in the form of abuse, torture, hatred, misanthropy, cynicism, blaming and victimhood, compounds the world’s suffering. Most sin is simply one person’s suffering passed on to another. This is not good. This is not beautiful.

The utility of suffering, then, is the opportunity it affords us to become better human beings. It is the engine of our redemption.”

(Link to original quote)

In season 1, Nick and June were shown as clear contrasts to Fred and Serena. In their own ways, each of these characters have suffered. (Remember, all humans suffer, although the degree to which it occurs obviously varies). Nick and June represented the utility of suffering. Both characters in season 1 transformed their pain into love—something that ignited them into action and bravery for multiple seasons. Fred and Serena took the other path. They perpetuated and passed their pain on to the people under their power.

This is why Nick’s redemption has always been more acceptable or complex than for characters such as Serena, Lydia, Wharton, and Lawrence. Nick’s early character arc already had him transformed by love. The regression in the end was weak and sloppy. Serena, while she’s had her moments, has adamently chosen Gilead ideology over and over again. Even when she got out and even when she had clear choices.

Redemption doesn’t come from one useful (but still selfish) act at the end of a long chain of horrors and abuse. It doesn’t come only from guilt and self-loathing. Redemption begins through transformation. In the end, I didn’t see transformation from Serena. I saw regret that her choices didn’t work out the way she wanted, but throughout the seasons, she has still perpetuated and supported Gilead ideology. Aunt Lydia’s transformation was also extremely rushed and didn’t feel genuine enough (though they’re probably saving that for the Testaments). Even Lawrence, who had a better character arc, still only chose to work with Mayday for the selfish reason of wanting to stay alive when the other Commanders were going to kill him.

Nick’s potential for redemption was always there. He had transformed into someone willing to sacrifice whatever it took for the people he loved. This is why it frustrates me when people say he only helped June because he loved her. Like that’s a bad thing? To risk your life over and over again out of love? That is good. That is beautiful. That is evidence of a personal transformation.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Betrayal of Nick Blaine: How The Handmaid’s Tale Undermined Its Own Storytelling

As a university professor with a PhD in literature, I’ve dedicated my career to analyzing narrative structure, character arcs, and thematic coherence. And I can say this with full confidence: what the writers did to Nick Blaine in Season 6 of The Handmaid’s Tale was not bold, subversive, or daring — it was a narrative betrayal.

And just to be clear: I’m not a shipper. I didn’t love Nick because of his romance with June. I appreciated him as a deeply layered character — one whose quiet resistance stood in stark contrast to the more performative defiance of others. Not every act of heroism is loud. Nick’s resistance began long before June entered his life, and for several seasons, the writers honored that. Until they didn’t.

Nick represented something rare on television: a portrayal of a man caught inside a brutal system, not loud or showy, but quietly working to survive while retaining his humanity and fighting back in the ways available to him. His arc was thoughtful, subtle, and realistic — and it offered a necessary counterpoint to the broader, more visible forms of rebellion in the series. That narrative was coherent, moving, and consistent — until Season 6 shattered it for the sake of shock value.

A HISTORY OF RESISTANCE — CAREFULLY BUILT

Nick’s arc was never centered on power. In fact, he resisted it. He smuggled contraband to Jezebels, joined the Eyes in order to report predatory Commanders (after Waterford’s first Handmaid died by suicide), and helped take down Commander Guthrie, one of the architects of the Handmaid system. These weren’t incidental moments — they were intentional signs of internal rebellion that the show carefully planted over multiple seasons.

After meeting June, Nick continued to act strategically. He was the one who secretly smuggled the Jezebels letters out of Gilead and delivered them to Luke in Canada — an act that directly led to Canada refusing to sign a diplomatic agreement with Gilead. And crucially, Nick did this without June asking him to or even knowing about it. At the time, June was in a terrible mental state, so desperate that she tried to burn the letters in the sink. Nick hid the Jezebels letters in his apartment before Eden moved in — making it all the more risky once she arrived and began snooping through his things.

His promotions weren’t rewards but consequences. Serena arranged his marriage to Eden out of jealousy. His rise to Commander wasn’t a reward for loyalty — it was a consequence of his decision to pull a gun on Fred to help June and Nicole escape, as even Joseph Fiennes has confirmed in interviews. Even his marriage to Rose served a clear purpose: to get closer to Hannah’s captors, the Mackenzies, and position himself in a place where he could act.

Importantly, the Marthas in Season 4 speak to Nick like an equal, not like someone they fear. One even asks him, “Is this business as usual?” — a small but significant clue that Nick had been working with the Martha network for a long time. This wasn’t a sudden shift. His ties to the resistance were consistent and deliberate. Even other Commanders call him a “boy scout” in Season 6 — a nickname that reflects his perceived moral rigidity and difference from the men around him.

THE HINTS THE WRITERS LEFT — THEN ABANDONED

Throughout the first five seasons of The Handmaid’s Tale, the writers laid down clear and deliberate hints that Nick was meant to function as a quiet resistor embedded within Gilead’s system. His actions were not accidental or incidental — they were purposeful choices, woven into the narrative to build a coherent, morally complex character.

Another major hint came in a cut scene from Season 3 — one that never made it to the screen but is preserved in the official scripts. In that scene, Nick is shown at the front during Gilead’s military campaigns, standing alongside Commander Mackenzie. This wasn’t designed to show him as complicit — quite the opposite. It placed him close to Hannah’s captors, setting up his position to act as an inside link, a person who might eventually help June find and rescue her daughter. This scene reinforced what the show had been quietly building all along: Nick was where he needed to be, playing the long game.

His abrupt marriage to Rose further aligned with this arc. It wasn’t a romantic choice or a reward — it was another calculated move to get close to the Mackenzie family. The fact that we saw him and Rose at dinners with them in Season 5 wasn’t coincidence — it was strategy. Nick was positioning himself exactly where he could observe, influence, and perhaps, one day, act.

And here’s something telling: in his apartment above the garage, we see Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel García Márquez. That’s not just a random prop. It’s a novel about enduring love and resistance in the face of cruelty and loss. The writers deliberately placed that book in his apartment. It was a clear, intentional signal: Nick was written as someone with inner depth, quiet resistance, and a poetic soul. Bruce Miller says in The Art and Making of The Handmaid’s Tale:

“We were very careful about what books he reads, what books he has, and where we got them.” (p. 34)

And yet, all of these threads were dropped in Season 6. The Mackenzies vanished from the story. The careful groundwork that had been laid for Nick’s internal resistance arc was erased, discarded in favor of a last-minute, illogical narrative pivot that portrayed him as complicit without reckoning with everything the show had previously told us about him.

What’s worse, both the show’s own deleted material and the actual scenes up until Season 6 make it clear that Nick was never meant to be the villain they later tried to paint him as.The official scripts and cut scenes show him as a man horrified by the violence of Gilead’s rise, caught in it but never fully part of it. These clues weren’t just abandoned — they were actively contradicted in a way that undermined both the character and the larger themes of the series.

WHAT THE CREATORS & ACTOR SAY

Before Season 6, both the creators of The Handmaid’s Tale and actor Max Minghella consistently described Nick as a fundamentally decent man — a character carefully constructed to be morally complex, but not complicit in Gilead’s ideology.

Max Minghella, who portrayed Nick, made his view of the character clear as early as 2018:

“I trust Nick. I stand by him … at the root of Nick, he’s a good person. Whether he always does the right thing is a different question.” (Glamour, 2018)

Minghella recognized Nick as morally conflicted but ultimately decent — a man navigating impossible choices in an impossible world. His performance was built on the understanding that Nick was not a villain, but a man trapped by circumstances beyond his control, revealing himself through small gestures and quiet decisions.

In 2022, at the end of Season 5, showrunner Bruce Miller reinforced this characterization:

“I know what we’re setting up for Nick, which is exactly what you think it is. He’s the guy who we think he is. And even if he tries not to be the guy he thinks he is, it’s either going to be very uncomfortable for him like he is with Rose, or it’s going to fail and he’s going to end up not being able to stop himself from punching Lawrence. I think the nice thing is he follows his heart, and the scary thing is he follows his heart.” (Deadline, June 2022)

This statement from Miller is especially revealing in light of what ultimately unfolded in Season 6. His words confirm that as of the end of Season 5, Nick was intended to remain exactly as the audience understood him: a man driven by emotion, not ideology; someone uncomfortable when forced to conform; someone who couldn’t suppress his decency even when doing so put him at risk.

However, after Season 6, Miller’s commentary took on a different tone, attempting to reframe Nick’s arc:

“Nick isn’t choosing Gilead as a sudden endorsement of its beliefs and practices, but rather a belief that there’s no beating this regime; it’s better to protect yourself by moving with it rather than against it.” “Nick was trying to stay out of trouble … thinking about how to keep himself safe for his family.” (TV Insider, 2025)

These post-finale remarks sought to justify Nick’s sudden portrayal as complicit in Gilead’s horrors, but they stand in stark contrast to Miller’s earlier statements. What happened in Season 6 was not the culmination of a long-planned character journey; it was a last-minute pivot that abandoned Nick’s carefully built arc. His proximity to Gilead’s power structures had always been framed as about survival, not ideology — a distinction that Season 6 discarded.

Even Minghella was surprised by the shift in Nick’s moral framing, as he revealed in an interview with ELLE in 2025:

“Transparently, I was surprised … I thought it was a really bold and interesting choice to bring that story into this more nihilistic viewpoint.” “Maybe I hadn’t been playing this character correctly the whole time … there was probably a darker side to him that I didn’t realize was there.”

When even the actor playing Nick for six seasons no longer recognizes the character he’s portraying, it highlights how drastic and jarring the shift in writing was. Nick’s final arc wasn’t the result of a gradual, coherent evolution — it was a sudden, dissonant rewrite that undermined everything the audience, and even the show’s own team, had come to understand about him.

Where once the creators framed Nick as a survivor and quiet resistor, they later attempted to retroactively paint him as complicit. This contradiction is not just a failure of internal consistency — it’s a betrayal of the character they themselves had worked so carefully to build.

A SHIFT BEHIND THE SCENES — AND ONSCREEN

The betrayal of Nick’s arc didn’t happen in a vacuum. It was the result of major shifts behind the scenes that dramatically altered the show’s direction and tone, particularly in Season 6.

After Season 4, there were significant changes in the writers’ room, and after Season 5, Bruce Miller — who had been the showrunner and primary architect of the series’ complex moral landscape — stepped down as showrunner to focus on developing The Testaments adaptation. What followed was a tonal and narrative shift that was most starkly reflected in the treatment of Nick’s character.

In Season 5, the writers appeared to be setting up Commander Lawrence as the morally compromised figure whose choices would catch up with him. Lawrence, after all, had designed Gilead. He was one of its architects — a man who wielded enormous power and made decisions that cost thousands of lives, including the bombing of Chicago and the systemic torture of women. He was unwilling to help June find Hannah, even when she begged him, and he stood by as Gilead shot down American planes attempting to raid Hannah’s school. He didn’t intervene to stop this act of brutality, just as he never truly opposed the suggestions of other Commanders to have June killed when she became too much of a threat. But reportedly, Bradley Whitford — who plays Lawrence — pushed back against having his character face the full consequences of those choices.

So what did the writers do instead? They redirected that arc onto Nick. Rather than grappling with the moral failings of Gilead’s true architects, the show chose to scapegoat the one male character who had consistently resisted, quietly and at great personal risk, from the inside.

The result was a jarring pivot in Season 6, where Nick was denied the nuance and complexity afforded to characters like Serena, Lydia, Lawrence, and even Naomi Putnam. Naomi, a character who had benefitted enormously from Gilead’s brutal hierarchy and who had always relished her privileged position, was suddenly handed a redemption arc without narrative justification. Her decision to give Charlotte to Janine came out of nowhere, contradicting everything we had seen of her character before.

Meanwhile, Nick — who had quietly resisted for years, who had risked his life for June, Nicole, and the resistance — was given no such grace. His entire arc was collapsed into a simplistic and inconsistent portrayal of complicity, as if all his sacrifices and small acts of rebellion had never happened.

The complexity that had once made The Handmaid’s Tale so compelling was flattened in favor of a reductive, black-and-white view of its characters — one that betrayed both Nick and the show’s own core themes.

THE GASLIGHTING OF FANS

To make matters worse, in the wake of justified fan backlash over the abrupt and illogical rewriting of Nick’s character, the public statements from the show’s creators, writers, directors, and even lead actor felt like gaslighting. Rather than acknowledging the inconsistency or taking responsibility for the narrative pivot, they shifted blame onto the audience — particularly the female fans who had thoughtfully engaged with Nick’s arc for years.

The writers claimed that viewers misunderstood Nick because “we don’t see 95% of the things Nick does in Gilead.” This was offered as an explanation for why fans were supposedly confused — suggesting that any contradictions in Nick’s character came not from inconsistent storytelling, but from unseen off-screen actions. The writers also implied that fans had misjudged Nick because they saw him primarily through June’s eyes, and that her love for him clouded both her perception and, by extension, that of the audience. This framing felt deeply patronizing. It reduced thoughtful, critical engagement with the character to the idea that fans (especially women) were simply too emotionally attached to see the truth. The creative team further argued that Nick had plenty of chances to leave Gilead but chose not to, reinforcing their revisionist narrative. What makes this claim especially disingenuous is that the show itself repeatedly demonstrated how difficult, if not impossible, it was to leave Gilead. Even Lawrence — a man with immense power — tried to leave in Season 3 and couldn’t. To suggest that Nick could have simply walked away contradicts the very world-building the writers established.

And then Eric Tuchman went on to claim:

“Even though Nick is a wonderful savior and protector for June and Max Minghella is an incredibly charismatic actor with wonderful chemistry with Elisabeth Moss, Nick has a life beyond June in Gilead. We’ve known since Season 1 he was an Eye, as well as a driver. The Swiss didn’t want to talk to Nick because he was a war criminal and couldn’t be trusted. Serena told June, ‘Didn’t Nick tell you what he did? To help create Gilead?’ — and it was something ominous. June chose not to ask any further questions. We know that he bombed Chicago and a lot of innocent people were killed — June and Janine were there. Yes, he was following orders, but Nick has always been a fully willing participant in Gilead. He’s always embraced Gilead. The only times he ever helped the resistance were because of his connection to June. She has been his beacon to do the right thing. Nick’s betrayal was proof he wasn’t really part of the resistance.” (Cast Q&A, @handmaidsonhulu on Threads, 2025)

But these statements are deeply misleading. They ignore what the actual canon of the show established and contradict the very material the writers originally produced. The Swiss refused to talk to Nick not because of war crimes, but because of optics and politics — as shown in official deleted scenes and the scripts archived at the Writers Guild. In those cut scenes, Nick is portrayed during the rise of Gilead not as a war criminal, but as a minor guard, visibly horrified, described as “looking sick” at the violence unfolding around him. When a comrade is killed, Nick fires back “out of instinct” — hardly the mark of a man shaping or embracing the regime.

Another scene — one that did air — shows Nick returning a salute from Gilead troops. In the official script, this moment is described with a crucial note: Nick is “hating all the choices that led him here.” His internal conflict is explicitly spelled out, revealing that even in this small gesture of outward compliance, he is burdened by regret and trapped by circumstances. This wasn’t a man embracing Gilead’s ideology. It was a man caught in a web he couldn’t easily escape, trying to survive while carrying the weight of every decision that brought him to that point.

Bruce Miller himself confirmed that Serena’s ominous comment to June about Nick’s role in creating Gilead was a lie, meant to hurt her emotionally. And we know from canon that Nick objected to bombing Chicago, but didn’t have the power to stop it.

Director Daina Reid added fuel to the fire, directly targeting women in the fandom. In her Eyes on Gilead podcast interview, she said she “doesn’t understand these women who still defend Nick.” She went even further, claiming that viewers “invent scenes” to justify Nick’s actions — as if fans who had paid close attention to his arc were simply imagining things to excuse him. In doing so, she dismissed female fans specifically — implying that their continued support for Nick was irrational or misguided, and reducing thoughtful engagement with the character to naive emotionalism. This wasn’t just dismissive; it was a troubling attack on a loyal, thoughtful fanbase that had engaged deeply with the show’s themes of resistance, complicity, and survival.

Even Elisabeth Moss, who plays June, contributed to this gaslighting. In interviews, she misremembered key parts of the story — for instance, forgetting that Eden suspected Nick’s lack of sexual interest in her and feared he might be a gender traitor. This was a significant part of Eden’s arc, yet Moss appeared unaware of it, undermining her credibility when discussing Nick and June’s relationship. Moss also insisted in interviews that June “absolutely did not want Nick to die,” while simultaneously suggesting that June could never forgive Nick for his so-called betrayal — despite the fact that if Nick hadn’t made that difficult choice in the moment, he would have died on the spot. The logic simply doesn’t hold: how can June not want him dead but also not forgive him for the very act that saved his life?

If we’re now expected to view Nick as a villain based on things we never saw, it’s not the audience inventing scenes — it’s the creators retroactively rewriting them. That’s not a failure of interpretation on the part of the fans; it’s a failure of storytelling on the part of the writers.

Adding to the irony, Elisabeth Moss recently explained in interviews that in respecting the book, they wanted to preserve a sense of open-endedness — to “keep a lot of loose ends” as the novel itself ends on a cliffhanger. Yet in doing so, they chose to alter one of the most crucial threads from the book: Nick’s arc. Adding to this contradiction, Bruce Miller himself asserted:

“I think the series has been good in large part because I chose to follow the story and tonal spirit of the novel as much as possible.” (Deadline, 2025)

If preserving the spirit of the book was truly the goal, they would have honored Nick’s role as Atwood envisioned it: a symbol of survival, moral conflict, and quiet rebellion.

What’s most telling is how drastically the messaging from the creative team has shifted. The Nick who was once described by Bruce Miller as a man of survival instincts, not ideology — a man navigating impossible circumstances while trying to protect his family — was suddenly reframed post-Season 6 as a willing and eager participant in Gilead’s horrors. This contradiction not only betrayed Nick’s character but also undermined the integrity of the show’s moral universe.

ATWOOD’S VISION, THE BOOKS, AND THE DANGER OF THIS REWRITE

Resistance from within is a hallmark of dystopian literature. From 1984 to The Hunger Games, these narratives often explore how individuals embedded in oppressive systems work quietly, strategically, and at great personal risk to undermine them. These characters are complex, morally ambiguous, and realistic — because real-world resistance is rarely loud or simple. The Handmaid’s Tale, as originally written by Margaret Atwood, understood this nuance, and Nick Blaine was designed to embody it.

Atwood herself envisioned Nick as a figure of internal dissent — a man trapped by circumstances, but capable of moral clarity and quiet rebellion. In The Testaments, set fifteen years after the events of The Handmaid’s Tale, Nick is still alive, still inside Gilead, and still working as part of the underground resistance. We see him reunite with Nicole, the daughter he risked everything to save, and we see that his arc was meant to reflect the endurance of hope and the power of resistance that survives even in the darkest places.

The show, for five seasons, respected this vision. Nick stayed in Gilead because that was his purpose — to help destroy it from within. His positioning near Hannah’s captors reinforced his role as an inside man. The writers kept him in Gilead because he was meant to be there, playing the long game. Until Tuchman and Chang decided they knew better than Atwood and discarded this crucial thread.

Atwood has been outspoken in her view that dystopian systems like Gilead harm everyone — men and women alike. As she has said:

“Patriarchy hurts men too. Totalitarianism hurts everyone — men and women alike.” (CBC, 2017)

And on feminism:

“Feminism is not about demonizing men. It’s about working with men so that everyone has the same rights.” (New York Times, 2018)

The show’s final season abandoned this fundamental ethos. Instead of portraying the complexities of complicity and resistance across genders, it simplified its moral world: all Commanders were framed as irredeemable, while even characters like Naomi Putnam — who had thrived under Gilead’s brutality — were suddenly offered redemption with no coherent justification. This flattening of moral nuance betrayed the depth and realism that had defined the show’s earlier seasons.

By erasing Nick’s internal resistance arc, the show not only disrespected Atwood’s source material but also weakened its own critique of authoritarianism. The danger of this rewrite isn’t just that it harmed a character — it’s that it undermined the very lessons dystopian literature is meant to teach us. It replaced complex truths about power, survival, and quiet resistance with simplistic, black-and-white moral judgments that serve neither feminism nor thoughtful storytelling.

Nick’s character was supposed to remind us that even those caught inside the machinery of oppression can still fight back in their own way. Erasing that lesson robbed the audience of hope — the most vital tool dystopian fiction can offer.

NICK’S ATTRACTIVENESS AND THE MISOGYNY BEHIND THE CRITICISM

One of the most troubling aspects of the backlash against Nick’s character — and against the fans who continue to care for him — is the way his physical attractiveness has been weaponized as a reason to dismiss thoughtful engagement with his arc. Critics, including members of the show’s creative team, have implied that fans (especially women) only care about Nick because of his looks — as if audiences are too shallow or simple to appreciate deeper qualities.

Disturbingly, this attitude wasn’t just reflected in off-screen commentary. It became embedded in the writing of the final season itself. After five seasons in which no character ever explicitly commented on Nick’s appearance, Season 6 abruptly shifted focus, framing his physical attractiveness as the defining reason June loved him. For the first time, June says that she would have noticed Nick even if he were bagging groceries or driving for Uber because he was very handsome. Moira joins in, comparing Nick’s looks to Rihanna’s and rating his hotness as if she were judging a celebrity. Even Lawrence remarks that June was “swept away” by Nick’s “smothering looks.”

This was no accident. The writers deliberately chose to center Nick’s attractiveness in a way they had never done before — as if to validate their own revisionist narrative that June’s love for Nick was shallow, and that fans’ attachment to him was based only on surface-level traits. In doing so, they reduced what had been a deeply layered, emotionally rich relationship to a matter of lust and superficiality — diminishing not only Nick’s character, but June’s as well.

As brilliantly articulated in the Above the Garage podcast’s cathartic essay on Nick:

“Nick’s physical attractiveness has nothing to do with the reason we love his character. Women are not as simple and shallow as you’re making them out to be. No matter how someone may try to shame you, it is not antifeminist to believe in, and care about, romantic love. Our protagonist herself has said, many times, that it is for love that she lives. Love is empowering, and we thought that was a message the show understood.”

What Nick represents is not some idealized, flawless hero. No one who values Nick as a character denies his flaws or excuses his moments of complicity. What Nick offers is a vision of the human capacity for joy, tenderness, and compassion in the bleakest circumstances. His quiet support of June, his ability to love and be loved amid horror, reflects the reality that even in war, oppression, and captivity, people have found ways to fall in love, to marry, to create art, to dream of a better world. Nick’s story was an opportunity to show how resistance can be sustained not just through defiance, but through humanity and connection.

The suggestion that shipping Nick and June, or simply caring about Nick as a character, is somehow naive or antifeminist, fundamentally misunderstands the complexity of these relationships. As the essay points out, the show could have leaned into Nick and June’s profound connection — a connection that empowered June, supported her agency, and could have stood as one of television’s greatest romances, without undermining the power of her friendships or her other relationships. Life is not either/or. Women can value deep friendships and romantic love. The audience can appreciate both without one diminishing the other.

Finally, it’s important to call out the hypocrisy in how romantic love is treated. As the essay puts it: “You know who else thought romantic love was naive and silly? Our old friend, Fred Waterford. May he rest in peace.”

Dismissing viewers who value love and connection as naive is not progressive — it echoes the mindset of the very villains the story sought to critique. It is not antifeminist to care about love, or to see beauty and strength in a character who represents its survival under tyranny. And it is certainly not a weakness or character flaw to find meaning in these narratives.

THE DANGEROUS MISLABELING: NICK AS A “NAZI”

One of the most disturbing narrative choices in Season 6 was the decision to have multiple characters — including June’s mother, Holly, and Luke — refer to Nick as a “Nazi.” This label was not used in earlier seasons, despite Nick’s long-standing position within Gilead’s structures. It was introduced only in Season 6, coinciding with the writers’ abrupt pivot toward framing Nick as complicit and irredeemable.

The comparison is not only morally and historically inaccurate — it is dangerous. Nick is not portrayed as an architect of genocide, nor as a willing enforcer of Gilead’s ideology. As the show itself spent five seasons establishing, Nick is a survivor — a man who joined the Eyes not to impose tyranny, but to report on and take down predatory Commanders after witnessing the suicide of Waterford’s first Handmaid. He smuggled contraband, helped the resistance, facilitated June’s and Nicole’s escape, and positioned himself near Hannah’s captors in hopes of aiding in her rescue. These are not the actions of a true believer in the system; they are the actions of a man trapped within it, trying to undermine it where he can.

Calling Nick a Nazi collapses the moral complexity that The Handmaid’s Tale once prided itself on. It flattens the nuances of complicity, survival, and resistance into simplistic, black-and-white thinking that does a disservice not only to Nick’s character but to the audience’s understanding of history. Gilead is a fictional regime meant to reflect elements of real-world authoritarianism, but equating every man in a uniform with a Nazi trivializes both the horrors of the Holocaust and the lived realities of people trapped within oppressive systems who did not have the power to change them, but found small, courageous ways to resist.

It’s also worth noting that the writers making these choices surely have not lived under totalitarian regimes themselves — which cannot be said about many of the show’s viewers. For those who have experienced or have family histories marked by real-world authoritarian rule, these labels are not just inaccurate; they are deeply offensive and reflect a dangerous misunderstanding of what life under such regimes actually entails.

June’s mother’s use of the term might be explained by her extremism and ideological rigidity — but when Luke adopts the same language, it becomes clear that the writers themselves wanted to frame Nick through this lens, erasing the character they had spent five seasons building. This lazy labeling serves neither history, feminism, nor good storytelling. It reduces complex questions about survival, complicity, and moral ambiguity to cheap, inflammatory rhetoric — the opposite of what dystopian fiction is meant to encourage us to grapple with

WHY THIS MATTERS

Nick didn’t need a heroic ending. But he deserved a consistent one. His arc represented a type of resistance that is rarely shown on screen: strategic, quiet, and deeply human. Nick’s story gave voice to the reality that not all acts of rebellion are loud, and not all heroes stand on podiums. His form of dissent — subtle, calculated, often invisible — was no less important than June’s louder, more visible defiance. In fact, it reflected the kind of resistance that most people caught inside authoritarian regimes actually engage in: the quiet, careful acts that chip away at power without drawing lethal attention.

More than that, Nick was the show’s most realistic character. He was an ordinary man swept up by the rise of Gilead — lured into the Sons of Jacob not out of malice or ideology, but because of the brutal socio-economic conditions that preceded Gilead’s rise. Like many who find themselves caught in the machinery of authoritarian systems, Nick became increasingly trapped as the years passed. But crucially, Nick almost immediately saw Gilead for what it was. He recognized the horror. And despite the danger, he chose to resist in the ways available to him — quietly, strategically, and at great personal cost.

We needed that Nick. His arc was supposed to remind us that even those inside the system, even those who have made mistakes, can choose to act with compassion, courage, and moral clarity. His story offered a rare and vital kind of hope: that decency can survive in the darkest of places, and that ordinary people can make extraordinary choices even when the odds are against them.

In the difficult times we live in, as extremism and authoritarianism rise in the real world, Nick’s story could have served as a reminder of the importance of quiet resistance — of the fact that the fight against oppression doesn’t always look like a revolution, but can begin with small, courageous acts.

By collapsing his arc into a simplistic tale of complicity, the writers not only betrayed Nick as a character but stripped the audience of that hope. What happened to him wasn’t just a sad ending. It was bad writing. And it was a missed opportunity — a failure to honor both the character they had built and the powerful tradition of resistance that dystopian fiction exists to celebrate.

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atwood Gave Us Love. The Show Gave Us Motherhood. (plus: lots of book references about love)

It’s weeks later and still unbelievable to me that after everything, after five seasons of resistance and rage and survival and pain, the THT writers chose this path. That The Handmaid’s Tale, which once fought so hard to dismantle Gilead’s ideology, is now echoing and affirming it. That it dares to let Fred Waterford be right.

“You can fulfill your biological destiny in peace. What else is there to live for?” June answers with one word: “Love.”

It felt like the clearest rejection of Gilead’s entire philosophy: a moment that reaffirmed the show’s feminist spine. June wasn’t choosing safety or submission. She was choosing herself. She was choosing love. And to see that truth now being unraveled, to watch the narrative quietly suggest that her real fulfillment lies in motherhood, not in passion, not in resistance, not in choice. I’m still in utter disbelief. It’s not just disappointing. It’s fundamentally anti-feminist.

That’s why that scene in Season 1 haunts me. It’s not rhetorical. It’s not idealistic. It’s a visceral rejection of everything Fred stands for. June isn’t trying to win an argument. She’s reclaiming something sacred. Something Gilead tried to erase. She’s talking about Nick. About a love that refused to die even when everything else was stripped away.

And that moment wasn’t just powerful in the show. It directly echoes the original exchange in the book, where the Commander says nearly the same thing:

“This way they’re protected, they can fulfill their biological destinies in peace. With full support and encouragement. Now, tell me. You’re an intelligent person, I like to hear what you think. What did we overlook?” “Love,” I said. “Love?” said the Commander. “What kind of love?” “Falling in love,” I said. “Oh yes,” he said. “I’ve read the magazines… Was it really worth it, falling in love?”

Atwood gives us the answer with everything that follows. Through the way Offred holds onto Nick, not because he is a hero or a savior or even safe, but because he is real. Because what they have exists outside of role and function and fear. Because he sees her. Because love, in a world like this, is resistance.

And yet, in the show, they’re walking that answer back. June’s love for Nick, the thing that made her human again, that brought her back into her body, her desire, her agency, is being quietly pushed aside. Not because it stopped meaning something, but because it’s inconvenient. Because it doesn’t “fit.” Because Luke is the man who represents family and healing and safety and fatherhood. And Nick? Nick is chaos. Nick is longing. Nick is choice.

It’s the same choice she makes in the book. Over and over again, Atwood writes about love as something radical. Something terrifying. Something that gives you back to yourself. There’s that beautiful line:

“But this is wrong, nobody dies from lack of sex. It’s lack of love we die from.”

June doesn’t cling to Nick because she needs sex. She clings to him because she needs love. Because that’s what Gilead stripped from her, not just bodily autonomy, but emotional truth. And Nick gives her that back. Not perfectly. Not without pain. But honestly.

Atwood makes that point again and again: that love is remembered not just as a feeling but as something felt in the body, something vivid and grounded and alive:

“I kneel on my red velvet cushion. I try to think about tonight, about making love, in the dark, in the light reflected off the white walls. I remember being held.”

That’s what love is under Gilead: not a fantasy, not an escape, but a memory you fight to keep. Something that tethers you to your own humanity. A flash of being seen.

There’s also this:

“We make love each time as if we know beyond the shadow of a doubt that there will never be any more, for either of us, with anyone, ever… Being here with him is safety; it’s a cave, where we huddle together while the storm goes on outside. This is a delusion, of course.”

Even when it’s not safe, even when it’s built on delusion, it matters. Because that’s what it means to choose love in the middle of collapse. That’s what June and Nick always were. They were the cave. They were the thing that made the pain bearable.

So how can the show now pretend that motherhood was the point all along?

That what June needed was not passion or partnership or desire, but a stable household with a man who didn’t know her in the dark? How is that feminism?

It isn’t.

Because what they’re doing now, whether they realize it or not, is elevating motherhood at the expense of womanhood. They’re saying June is fulfilled not because she found love in a hopeless place, but because she returned to her “destiny.” And that is a cruel message for any woman but especially for the ones who’ve already had their personhood erased.

It says: you can be complicated, but not too complicated. You can burn it all down, but in the end, you better come home. And what does “home” mean? Luke. Family. Safety. Function. Motherhood. A box.

It raises up the white mother. Again. It centers her journey, her pain, her peace, and leaves everyone else behind. It positions June as exceptional because she gets to go back. She gets to “choose” the right kind of womanhood, the kind that’s quiet and soft and digestible.

But June wasn’t supposed to be digestible. She was supposed to be a flame. A scream. A woman who wanted and didn’t apologize for it. Who believed that survival without love wasn’t enough. And now? The show is telling us it was. That in the end, Fred was right. Love was just a myth. And peace is when you stop asking for more.

And worst of all: in the end, she betrays that love. Not with heartbreak. Not with sacrifice. But with a kind of self-righteous, untouchable performance of feminism that’s been completely stripped of its emotional core. She lets Nick go, not because it’s too hard, not because it’s too dangerous, but because the show has decided she doesn’t need love anymore. Just motherhood. Just survival. And that’s what she’s left with. A man she doesn’t really see. And nothing else.

Ick. Ick.

But that’s not what the book says. That’s not what the story was built on. Love was always the thing. Even when it hurt. Even when it faded. Even when it was only there in the margins. Love was the refusal to become numb. It was what separated you from them.

“The more difficult it was to love the particular man beside us, the more we believed in Love, abstract and total. We were waiting, always, for the incarnation. That word, made flesh.”

Nick was the incarnation. He wasn’t abstract. He was real. And now the show wants to tell us that wasn’t enough?

I can live with ambiguity. I can live with tragedy and heartbreak. I can even live with June and Nick not ending up together, if that choice were rooted in character, in reality, in the mess of love and loss. But I can’t live with this story ending by saying love didn’t matter. That it was a phase, a detour, a narrative inconvenience. That a woman’s purpose begins and ends with what her body can do. That desire, freedom, and selfhood are indulgences, and motherhood is the only path to redemption.

That isn’t nuance. That’s a return to the very ideology this story once existed to destroy.

And it’s not just about June. It’s about what the show is saying to all of us. That in the end, we’ll all come home to the same role. That no matter how much we burn or scream or fight, we are just vessels. That our “destiny” is written in blood and womb and silence. That love, the kind that upends you, defines you, liberates you, is less important than being someone else’s stability. Someone else’s idea of safe.

As women, we are more than our biological destiny. We are more than mothers, more than partners, more than sacrifices. We are allowed to want. We are allowed to choose love. We are allowed to choose ourselves.

And I will never accept a story that asks us to forget that.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve tried to let it go but I can’t.

Everything THT did after the season 4 finale has been trash.

Seasons 5&6 could have been Nick & June uniting and becoming a part of the resistance.

It would have been so much more powerful to see the inner workings of a rebellion and the juxtaposition of June and Nick’s inner conflicts as they navigate change and the parts of themselves that were complicit in the rise of Gilead (yes, BOTH of them).

To move beyond the books and continue the tv series doesn’t mean an abandonment of the original themes and motifs. It’s about asking the right questions: What do those look like post escape? How do they present in Canada? Do they evolve or stay the same? What does the evolution of these themes look like?

Nick giving Fred to June isn’t as simple as, “his love language is acts of service.” Dude committed treason. That’s as much a declaration of loyalty as any and a flag flown that is not Gilead is inherently traitorous. If you didn’t think he was anti before, there can be no doubt now.

But they would have us believe his love is one dimensional. That it only extends as far as his reach to June. Sure, okay. Don’t show us what allyship looks like. Don’t show us what love and strength and support can do for a person who believed they might never see that for themselves.

And June whose greatest strength is her heart— what an opportunity to show what happens to someone whose love is twisted and manipulated, not just by Fred, but by Serena. There was an easy route between justified violence and a path to healing. And that path could have been lit by the same beacons who helped her find the strength to stay alive in Gilead: Janine, Alma, Brianna, Emily, Rita, and Nick. Hell even Aunt Lydia, who promised to watch over baby Holly.

Not to mention that’s also your in for a Lydia redemption. If June must be the pole all the ribbons tie back to, then why not actually use her. Lydia could easily feel a higher calling to June’s girls after being made a de facto godmother. To believe it is now well within her divine right to keep an eye on Hannah. Cut to her seeing the actual quality of life for these girls who are children and therefore innocent and pure insofar as a Lydia character is concerned, as opposed to these “ungodly” women she’s attempting to make “righteous.” It’s as good a catalyst for change as any.

And in all of their desperation to put moms on a pedestal, they overlooked an opportunity to showcase motherhood in all its aspects. Because guess what? SOME MOMS ARE BAD MOMS. Some are bad people. Some are hateful, selfish, oppressive people. “June was appealing to the mom in Serena.” SERENA IS A BAD PERSON. SERENA STEALS BABIES. SERENA BEATS AND ASSAULTS OTHER WOMEN. SERENA USES CHILDREN AS MANIPULATION TACTICS. SERENA BELIEVES IN GILEAD AND ALL ITS TENETS.

She believes possibly more than Fred, at least to start. In the flashbacks we see how she pushed him toward Gilead from the beginning. It’s Serena giving the speeches, not Fred. It’s Serena in the movie theatre invigorating the fight in them, not Fred. Even as he stood conflicted, wanting to fight for her voice in that boardroom, she insisted it was a sacrifice she had to make. When she’s lying wounded in the hospital, she basically calls him a pussy so he runs and kills the dude. I’m not saying Fred isn’t bad on his own, but to quote that dumbass traditional saying (and these two are nothing if not traditional): Fred is the head, but Serena’s the neck.

Basically, Serena is the Commander and Fred is her soldier.

Until she’s not.

And only then, when she feels just a fraction of the weight of the life she fought for; only when she’s uncomfortable, does she care. So, when Serena fights for women to read it’s only because she wants to be able to read.

Because Serena only fights oppression after it oppresses her. Because it’s not about the rights of the people, it’s about her individual autonomy. And the second she realizes a version of power exists for her in DC she reneges on her decision to let Holly go.

And to that I have to wonder: what kind of man would a woman like that raise?

But sure, let’s redeem Serena. Let’s give her a fighting chance. Because she’s a mother and all mothers are inherently good right?

Missed opportunity after missed opportunity.

And it’s infuriating because an actual impactful ending was right there.

Lydia vs Serena — 2 women with a similar belief system. One who can change. One who doesn’t want to.

Nick vs. Fred — Men compelled by the women they love. One who chooses to liberate. One who chooses to oppress.

These 4 characters who are moved and transformed, for better or worse, by the roles of June, Hannah, and Holly— with June as the narrative voice at the center and her daughters as the plot device that pushes her story, and the stories of everyone around them, forward.

Because humans are not stagnate. Stubborn though we may be, even when we fall into the worst of ourselves we are still moving.

Instead we watched them all rock back and forth on the same stupid pattern to the point that the only option for an ending was heavy handed soap box monologuing.

Instead they offered up a story that lacked hope. That lacked the belief that love can change us. That implied trauma makes us cruel and single minded entities for revenge. That forgiveness can only come to those whose self lies in their small children. That salvation lies in your ability to give birth.

Because in the end, if Serena could not have conceived Noah, would she still have been worthy of her redemption?

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

I never post these, but yeah….pay attention because ALL of this 👇👇👇👇👇

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

the hunger games adaptation is like "acts of kindness and persevering human connection are just as important as an army" and then the handmaid's tale adaptation is like "if you're not a guns blazing martyr you're a fucking fash and you might as well kill yourself"

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been thinking of how The Handmaid's Tale writers just decided to have Nick's mother abandon him to his abusive father without getting into any of the details of it and I just- why? Why would they do that to him? It just didn't achieve anything other than establishing him as someone who was never loved, was trapped by circumstance, and who took a lot of things from June that he shouldn't have because he not only had daddy issues, but mummy issues as well.

I'm assuming their goal was to show him as some sort of incel/red pill/manosphere/whatever who believed in the messaging of the SoJ because his mother abandoned him and he had no good women in his life growing up? Which really does not work in him as a character for reasons that were upheld by their own writing even within this last season.

It seems like there was a total misunderstanding of those groups, likely even done on purpose, in an effort to sloppily send some sort of message and cling to current political trends. A key component of these groups is a disdain for women, and a desire to control and dominate. Which is the exact opposite of what we saw with Nick. Nick, who didn't hate any women (not even Serena who abused him and kidnapped his daughter, or his mother who abandoned him) but instead hated himself. Nick, who constantly gave up control to the women around him (and not just June, but other women like Beth and his black market contact Marthas, Lori and Reese) and who more than happily let June dominate him, often to his detriment. Yes, Nick wanted more control over his life in a way the US and unfettered capitalism denied him, but that's not the same as wanting control over everything, women included. It's normal to want to have more control over your life, it's not to want to have control over others. And the latter is something we just never saw over Nick. In fact it's something we did see in Serena. But she's a wealthy white woman, so I guess it was ok for her to want to control others, and terrible that Nick, a mentally ill working class man of colour, to want more control over his own life.

In the end all they really achieved was writing Nick as a character that has been unloved his entire miserable life despite making sacrifices for the people he loved, and that's really just depressing as fuck.

95 notes

·

View notes