Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Roman Opalka, 1965/1-∞

Why would someone paint sequential numbers? While waiting for his wife in a cafe, looking down onto a napkin, and wondering when he would die. After thinking of his own death, Opalka wondered how much time it would take him to count towards infinity, and choose in that moment to embark on writing every single number until he reached infinity.

To create his art, Opalka would start on one corner of the canvas and only move onto the next one after he filled it with numbers. There are over 200 canvas with numbers, and when Opalka died he had gotten to over 5 million.

The art in Polka’s work isn’t the canvas or ink, but rather the time it took to make the painting and the idea behind time, passing and end.

When seeing this photographs of Opalka, I begin to think of my own life. Am I going to reach my goals? What is my own infinity? I don’t know if I will reach all my goals, but I will work everyday of my youth towards them.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Treat Life like a Photo and simply take it in!

In chapter 1; The Second Coming of The Miracle of Analogy, Kaja Silverman employs poetic language to methodologically explore the metaphysical process of seeing. Silverman speaks of humanity's desire to conquer what we do not know about this process and critiques humanity's quest to "capture" a photo. Rather than try to control what we can not understand and reproduce, Silverman demands that we open our eyes. Utilizing prose-like language, Silverman presents deep conversation about this subject matter to call on photographers to live in the moment.

According to Silverman there are several steps that happen instantaneously that allow us to "see." Silverman explores the metaphysical process of seeing to allude that the present is past, and nothing is real. In brief, all that is in front of us happened before.

First, the seer's mind must "resemble a mirror, which always takes on the color of the object it reflects and is com-pletely occupied by the images of as many objects as there are in front of it.'" (Silverman, 17) The seer might experience the act of seeing as "passive" and assert the are simply receiving "emanations from the outer world,'" but for others they might experience seeing as an "'active'" experience where there eyes act as ray pointers that "cast out rays or a spirit to touch the seen object.'" (Silverman, 17) Then, the seer "....assigns new values to things that had seemed closed and irreducible..." (Silverman, 17)

In this process, Silverman explores how our eyes are highly advanced Camera Obscuras. Silverman asserts; "There is also a disconnect between the retinal images and what we 'see', which means that there must be an agency within us that reverses its reversal and inverts its inversions be-fore we perceive it." (Silverman, 19) Our rounded eyes see the world upside down like a Camera Obscura, but our brains flip this image. In this three step process, where we (1) see the world flipped upside down, but (2) our brains flip it back to normal, and (3) our brains then assign value to what we see, is the process by which we are able to see. This is how we navigate this world; always three steps behind.

Silverman elevates Descartes' proposition/contribution on this theory, highlight his comment that; "He (Descartes) urges those who do know believe that the inverted and reversed images of the external world appear on the surface of the retina to peel away the back layers of the eyes of a dead person or animal, insert it into the aperture of a camera obscura, facing outward, enter the camera obscura, and look at the retina from the other side. They will perceive images just like those that appear on the camera obscura's receiving surface." (Silverman, 18)

Realizing that our eyes are highly intelligent Camera Obscuras that automatically take-in rays of light to produce pictures, flip those images and create value and meaning; Silverman proposes the following; Do we have agency to see the world for what it actually is? Silverman, understanding that "There is also a disconnect between the retinal images and what we 'see'," propels the liberating possibility that we must then have "agency within us that reverses its reversal and inverts its inversions be-fore we perceive it." (Silverman, 19) To respond to this point, I declare that I would like to see the world bare, without a value system or fear. A tree is a tree is a tree, but what if it didn't have to? What other possibilities for seeing this world exist? Will I ever actually see the world?

Silverman then refutes this idiosyncratic argument by stating; "Surprisingly, these early viewers and practitioners did not rush to resolve the discrepancies between what they saw and what the camera showed by es-tablishing one as the truth and the other as an illusion….They understood that their look and the photographic image opened onto the same world-their world." (Silverman, 27) In this quote, Silverman demands that we situate ourselves. Instead of declaring that the way we see is ingenuine or false, I must accept and acknowledge that the current frame, however limiting and hindering, is the frame by which I can understand the world. What good does seeing the world do me if I can't understand it? If I didn't understand height or acknowledged height, I would die via mountain hiking. The way I have been socialized to see has removed my freedom to see and absorb the vast unknown but allows me to appreciate and realize the complex and dangerous world I live in. The highly advanced Camera Obscura that is my mind, is the conduit that hinders me and protects me. Silverman highlights; "But the camera obscura is much more for this eighteenth-century writer than an instrument of self-knowledge; it is the agency through which we learn to see the world differently." (Silverman, 24)

Silverman confronts the historical adage of seeking to conquer the image. Silverman asserts; "People began thinking of the camera obscura as a mechanism for ''taking likenesses,'..."(Silverman, 22) By trying to TAKE likeness, Silverman is calling out the people who seek to claim a moment or scene for themselves, unaware that whatever they captured belongs to nature, belongs to the past. Silverman gives the following contextual note; "...the verb 'to receive' figures much more prominently than the verb 'to take'" in early accounts of photography." (Silverman, 26) In understanding how language surrounding photography is increasingly more ego-centric, possessive and hierarchical, I REFUTE THIS LANGUAGE. When I take a photo, I am imaging the past, a past moment the Earth has already claimed. I have no authorship over the images I supposedly took. Maybe, instead of taking photos, I give photos. This language of taking photographs leads to photos being static and changeless. Silverman contends; "Like Descartes's 'clear and distinct ideas,' the drawings produced by tracing the outlines of the camera obscura's images transformed a mobile, ephemeral, and untotalizbale flow into a single, stable, circumscribed representation." (Silverman, 22)

Silverman segments to his third argument and most beautiful point of topic, we must look towards nature to realize real value and beauty. Silverman states; "Athanasius Kircher characterized nature as a 'painter'..." (Silverman, 23) By acknowledging Kircher's comment on nature as painter, I am inspired to see beauty in the natural world around me. The lake with its shades of blue and green blue, the hues of blue that the sky highlights every day which I can't fathom creating, the greens of the grass and trees around me. Silverman propels this argument by inserting that "Leonardo likened the camera obscura's images to 'paintings' and searched for other unauthored art works in the external world." (Silverman, 16) In my own value system, I must center the beauty of the natural world.

(1125/250 words)

0 notes

Text

KevinKevin

Mexican, b. Huntington Park, 1999-act.

Untitled Series (Supported, Inspired, Taught and still Learning) Gelatin on paper

ARTS 165: Intro to Photography, 2021.

Thursday, January 28, 2021

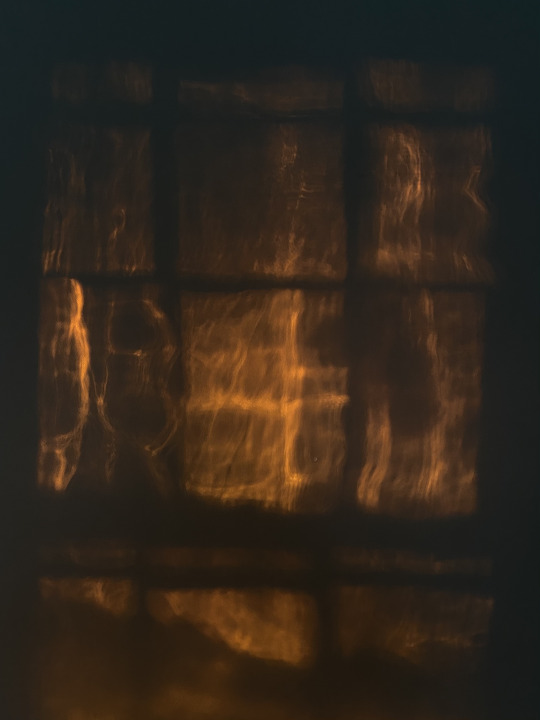

Finding an absolute dark space is actually hard.

As I sat there; uncomfortably in the criss-cross applesauce position in the small bathroom, I wondered if I would successfully find the matte side, without getting my fingerprints all over the glossy side. Equipped with the This App is a Light Meter app, I went outside trying to find somewhere where there was enough light, as the cold weather wind pushed small snowflakes onto my face.

Just because I want it doesn't mean I'm going to get it

Methodically placing my camera on top of a table, I got my desired shot. My first ever picture on the pinhole would be great. I would capture the way the sun's bright light interacted with the two trees in my backyard. Making sure to use the app correctly, I got the right time for the "shutter." I brought the lid covering my pinhole camera up, allowing light to enter and hoped for the best. After 15-17 seconds, I shuttered the pinhole, ran back to the bathroom, tried to take out the photo without touching any of its surfaces and tried the process again.

As I arrived at the Carriage House, entered the dark room and began the process of developing my image; conscious of the correct amount of time for each stage, I was confused, angry and upset that my PHOTO WAS NOT THERE!

In art terms, my first photo was very abstract. The sun against my skin, not too cold, and able to easily get my paper into the pinhole camera, I was confident that this image would be perfect. I would tell Alysia that I was ready to conquer what's next. But as I began to image my photo, instead of perfect, the image was undecipherable. "Do you know Ad Reinhardt? Look him up," Alysia said after showing them my picture.

I left the lab that day despondent, curious and excited. Despondent because I had followed all the rules. I had sealed the top of the camera, opened my paper in absolute darkness and waited the correct amount of seconds for the shutter. Curious, because Alysia told me that this was the photographic-artistic process. In my pursuit of the perfect picture, I would have to learn to work with my camera, not try to conquer it. I learned that more tape; a lot more tape was necessary to stop light from entering my camera. Excited, because what I saw as failing, Alysia noted as part of the experimentation process. Instead of being told to stop what I was doing completely, Alysia invited me to take more pictures, experiment with location and angle and do by failing, until the paper ran out. (Alysia always had paper to share.)

Sunday, February 7, 2021

The sun entering my room was so orange and bright, I thought it was summer. I quickly jolted out of bed, got ready and marched to the Carriage House. Today, I would capture my picture. Lessons I had learned: TAPE EVERYTHING. I taped everywhere from the top of the camera to the sides of the camera to the back of the camera, even the top of the pinhole. With all this tape, my pictures were now coming out a lot better.

As the sun was still out, I walked around the Art Campus trying to find the right shot. Then, on the second floor of the Carriage House, on the west facing window was the perfect picture, waiting to be taken. I ran back downstairs, loaded paper into my machine and got my timer ready.

22 seconds later, I ran downstairs, took my paper out of my pinhole camera and began the process. 1.5 minutes later, as my photo had finished the first stage of the process, I flipped my picture and saw it. On the paper was the view of the cemetery, the trees in the background, the tree branches in the foreground and ominous headstones and statues in the middle ground. It was a good picture. I took 3 more, not as detailed as the first, but still good. All in all, the process of capturing 4 pictures lasted 2.5 hours.

Walking amidst the blue hues of the sunset, I was contempt.

Tuesday, February 9, 2021

"How do I turn the machine on?" I thought to myself as I entered the darkroom. I had watched the YouTube video but I was afraid of breaking my bulb, moving the enlarger head out of place or messing with the focus knob. Do I put my picture in the film carrier? No, that doesn't seem right to me. How do I make sure my timer doesn't go off? Press the last button to the left. How do I change the numbers on my timer from whole numbers to decimals? Click the second to middle button once.

I had my negative image ready, I was now excited to use the enlarger to get my finished product; my perfect picture (in my eyes).

At first, I was adamant that my ideal time for the shutter ws 8 seconds, but my picture kept coming out lighter than I wanted. After 2 tries, Alysia told me to do a test strip. After doing my test strip, I got the right number for my image. For my image of the west-facing view of the cemetery, my aperture is 8 and I shine light on the image for 13 seconds. The final product, shown above, demonstrates that I know how to take an image with a Pinhole camera, process my image and successfully use an enlarger.

Who would have guessed that I would be able to conquer the paper camera? I didn't. Only through continued support, guidance and mentorship was I able to make this picture. Karina, Soule and especially Alysia helped me when I was navigating the different parts of this process.

I feel excited for the crit with Alsyia, thankful for everyone who helped me and especially grateful to Alysia for nurturing my creativity and dedication to making mistakes.

0 notes

Text

I mean; If my iPhone 11 is doing all the processing, what is my role?

I am embarking on Arts 165: Intro to Imaging to learn about photography. The real photography with the real camera, where the lensmxn manually, key word: manually, moves the lens and dictates the ISO and focus.

Before this course, I let my phone do all the work. Literally, the iPhone 11 begins to capture a rolling buffer of shots as soon as the Camera app is opened on my phone. And then, brilliant processing software selects the most crisp image. I, the unknowing iPhone "photographer," then is presented with the best image, the little processing beast that is my phone, selected for me to view. I then post these gorgeous photos to Instagram where everyone comments that I have a good eye and potential.

As I have been experimenting with my Pinhole camera, I realize I am nowhere near a real photographer.

Real Photography is romantic. A photographer inserts themselves into an image by manipulating it. Via manipulation, the viewer can feel the artist's presence. A photographer takes photos to capture a moment in the past that can never happen again. Imagine if we all navigated the world, conscious that no moment could be recaptured ever again.

Interested in capturing the human essence as is, un-privy to societal expectations, I am inspired by Catherine Opie. Seeking to capture the monumentality of the mundane, I look towards Andreas Gursky. Trying to present a wide angle to capture the vastness I exist within, I look to Thomas Struth.

In my own "photography," I try to capture the world without humans. I do so because environmental degradation due to human greed has resulted in the Earth's demise. When taking pictures, I pretend I am creating a book for my future generations. I want my descendants to see the world beautiful because of the Earth's natural beauty. I try to capture a natural world not paved in dark industrial concrete with brown polluted rivers.

I am excited to embark on this course. I really want to learn how to take wide-angle photos and learn best practices for capturing morning dusk and afternoon sunsets.

Hopefully I'll capture beauty on my own.

0 notes

Photo

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, "Untitled" (For Jeff), 1992. With multiple billboard locations throughout the greater D.C. area, as part of the exhibition Gyroscope. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, The Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 1 Aug. 2003 – 4 Jan. 2004. Photographer: Chris Smith. Image courtesy of Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, The Smithsonian Institution.

In “Untitled” (for Jeff), Felix Gonzalez-Torres presents a powerful artwork by scaffolding different photographic and presentation techniques.

First, Gonzalez-Torres takes an intimate portrait of Jeff’s hand, the caretaker tasked with caring for Ross Laycock; Gonzalez-Torres’ partner, while Laycock slowly succumbed to AIDS. Gonzalez-Torres zooms in the camera on the hand, ensuring no focus is lost, to emphasize that Jeff’s hand is the vehicle by which Jeff was able to demonstrate care and love to Laycock. It is with Jeff’s own hands, that Jeff is able to care for Laycock. The hand, merely a grasping organ attached to a bodily limb, is elevated to signifier of caring. Intimately, a hand is able to hold another hand, a hand is able to make tea when coughing, a hand is able to pat your stomach to soothe you. With a hand, you are able to care.

Gonzalez-Torres enlarges this intimate image, a personal momento that represents caring and love, and enlarges it. Next, Gonzalez-Torres enlarges this image of a Jeff’s hand, not attaching Jeff’s face to the hand, and places these enlarged billboards across different regions of the world. How is the meaning of an artwork altered/shifted when placed on a billboard (in public view)?

By placing Jeff’s hand, the signifier of caring for Ross Laycock; a victim of the AIDS epidemic exasperated by Ronald Reagan’s inability or unwillingness to act on the AIDS victims dying disproportionately in the United States and around the globe, Gonzalez-Torres makes the personal political. Moreover, Gonzlez-Torres calls upon us to activate our ability to care.

THE AIDS EPIDEMIC IS NOT OVER! WE MUST ACT-UP!

3 notes

·

View notes