Teaching at Queens College, CUNY. Author of Hard to Love, a book of essays on love and friendship. Writing at Los Angeles Review of Books, etc.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

A Monday morning pep talk

Evidence that we exist.

The only thing that is saving my life right now is the fact that I somehow managed to bang out a first draft of a book this summer. I did this by basically locking myself inside my house, which, in the New Orleans summer heat, is the only option anyway. And I just turned off the internet, put my head down and did the work every single day until I had something resembling a book.

It has been both a relief and a challenge these past few months making the book better than it was. I have shed a lot of tears over it. But just knowing that I have a more complete piece of work existing in my possession is an absolute lifeline for me during these absurd, insane and devastating modern times. Evidence that I existed and didn’t just float away on a sea of negative emotions in 2018. I put them somewhere, I made something out of this moment in time.

You can do it, too. Head down. Work hard. Save yourself. Make it matter. You might feel lost, but you’re not.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Four years ago today!

Get on Board the Blogtrain!

I’m grateful to Brook Wilensky-Lanford, editor extraordinaire of the soul-stirring religion magazine KtB, for tagging me in her blog train!

What am I working on?

Keep reading

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the Orchard

I come from a family that believes in regret, inertia, fatalism, and resignation. Luckily these are not the only things it believes in— we also practice unconditional love, enthusiasm, generosity, and wordplay— but on any given day my familial melancholy can feel like the most inexorable part of my legacy, as present as a skeletal ache on a rainy day.

Keep reading

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Birthday Aretha & Flannery

My friend Ash has gotten me into bodily resurrection lately via Flannery O’Connor. Let this song resurrect you.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

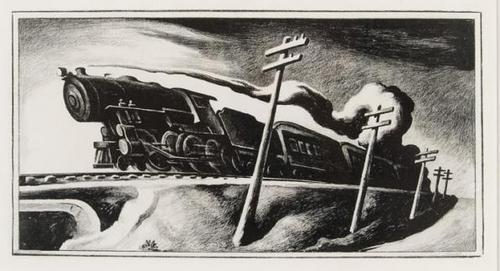

My Frederick Douglass Juvenalia

(I was so happy to run into Frederick Douglass at the Women’s March!) Long ago I wrote my senior thesis on Frederick Douglass, and it is a mess. But here is my favorite part of it: three stories about Frederick Douglass messing with people’s minds on trains, brought to you by baby Bri: In a prefiguring of W.E.B. Du Bois, Douglass uses trains as an ultimate proving-ground (or disproving-ground) for the validity of racial categories. (Once when Du Bois was asked to define blackness-- “But what is this group; and how do you differentiate it; and how do you call it ‘black’ when it is not black?”--he answered, “I recognize it quite easily and with full legal sanction; the black man is a person who must ride ‘Jim Crow’ in Georgia” [Zack 17].) One of the times when Douglass refuses to acknowledge the validity of racial categories is when he is ordered out of a first-class railroad carriage. The conductor says Douglass has to move because he is black, but instead of proclaiming to the conductor in ringing tones that “all the feelings, all the susceptibilities, all the capacities, which you have, I have,” Douglass refuses to, in Wiegman’s phrase, “obsessively perform” race, and instead simply denies that he is black: “This [his blackness] I denied, and appealed to the company to sustain my denial; but they were evidently unwilling to commit themselves, on a point so delicate, and requiring such nice powers of discrimination, for they remained as dumb as death” (Douglass 394). Douglass’s public denial of his blackness is breathtaking. On a pragmatic level the denial fits with some of Douglass’s other “humorous” responses to racism in which he turns racist notions upside-down as a way of dealing with fraught situations (for example when he assures whites that he has finally managed to overcome his prejudice against them, in order to defuse their uneasiness over his sharing a bed with a white man). But Douglass’s denial of his blackness has implications beyond its immediate practicality or humor. As Douglass never tired of saying (for example when a white man objected to Douglass’s daughter going to a white school, or when thousands of blacks objected to Douglass’s marriage to a white woman), he is as “white” as he is “black,” so in denying his blackness Douglass is mocking the arbitrariness of racial mathematics, just as Mark Twain would later in Puddn’head Wilson. And though Douglass is being ironic when he suggests that assigning race is a “delicate” point that requires “nice powers of discrimination,” his suggestion of the subtlety of racial designation lingers. Both Douglass’s blatant upside-down assertion and his unsettling sarcasm critique the broad-brush racialist categories of his contemporaries. In a sense, Douglass is denying his own body when he denies his racial designation, just as Stowe’s George Harris is denying his own body when he disowns “half the blood in my veins” because it is feeble, “hot and hasty Saxon” blood (Stowe 376). But Douglass denies his blackness in order to transcend his racial designation, while Harris denies his whiteness in order to emphasize his racial designation. In Wiegman’s words, by denying his racial designation, Douglass is refusing to grant the performance of race its centrality as “real” and observable truth, and the consequences are more than academic. The extent and implications of Douglass’s critique of racial categories can be seen when the account in My Bondage and My Freedom is read alongside a couple of his other train stories. Biographer William McFeely says that Douglass made the train incident ��stock in trade for his lectures” (McFeely 93); before he wrote My Bondage and My Freedom Douglass had already told the story many times. In a speech in 1847, he told it in the following version, which was taken down in third person by a reporter: “Once he was travelling in that district; he stepped into a Railway car at Lynn, and had not been there long, when a little white man also got in and ordered him to withdraw. He showed him his ticket; it was of no avail. The man still continued to demand that he (Mr. Douglass) should take himself off. He asked this person the reason why he made such a request, and he replied, ‘Why, you know you are a negro.’ ‘I denied it,’ said Mr. Douglass, ‘for you know,’ he continued, ‘I am but half a negro; betwixt and between, as they say.’” (Blassingame 6-7) In My Bondage and My Freedom, the interpretation of Douglass’s denial is left to the reader, but in this earlier telling of the story Douglass explains himself after the fact by saying that he is “betwixt and between.” Douglass’s recognition of his liminality, of what might be called his mixed race, undermines the validity of fixed racial categories. To completely establish his transcendence of racial categories, Douglass told a sequel anecdote a few years later, in 1851, in which he reversed his racial self-designation: “Indeed the white people are becoming more and more disposed to associate with the blacks. I am constantly annoyed by these pressing attentions. (Great laughter.) I used to enjoy the privilege of an entire seat, and riding a great deal at night, it was quite an advantage to me, but sometime ago, riding up from Geneva, I had curled myself up, and by the time I had got into a good snooze, along came a man and lifted up my blanket. I looked up and said, ‘pray do not disturb me, I am a black man.’ (Laughter.)” (Blassingame 341). By this time he finishes My Bondage and My Freedom, Douglass has already publicly identified himself as white-not-black, black-not-white, and mixed. If Douglass is at once negro and not negro, and neither negro nor not negro, then racial distinctions and hierarchies cease to make sense where he is concerned and thus cease to make sense at all if, as Wiegman argues, “the oppositional framework for articulating power depends on a homogenization of identities into singular figurations . . . The logic of ‘majority’ reaches an impasse when the social subject cannot be aligned, without contradiction, on one side or the other of the minority-majority divide” (Wiegman 7).

0 notes

Text

The Last of the Moores

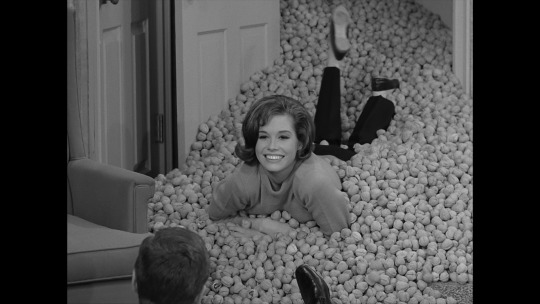

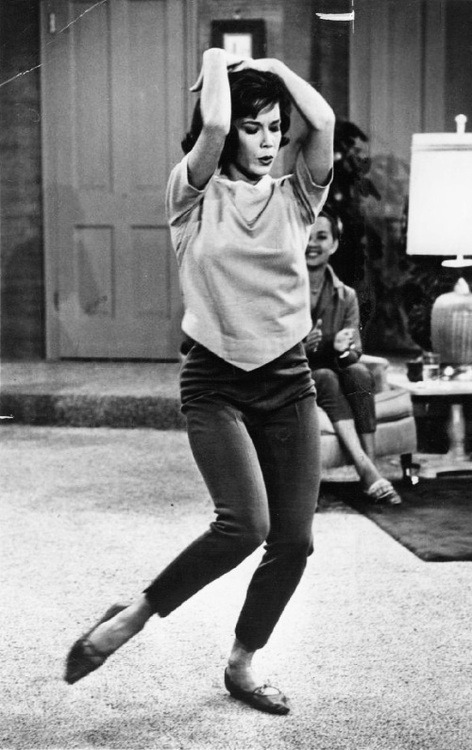

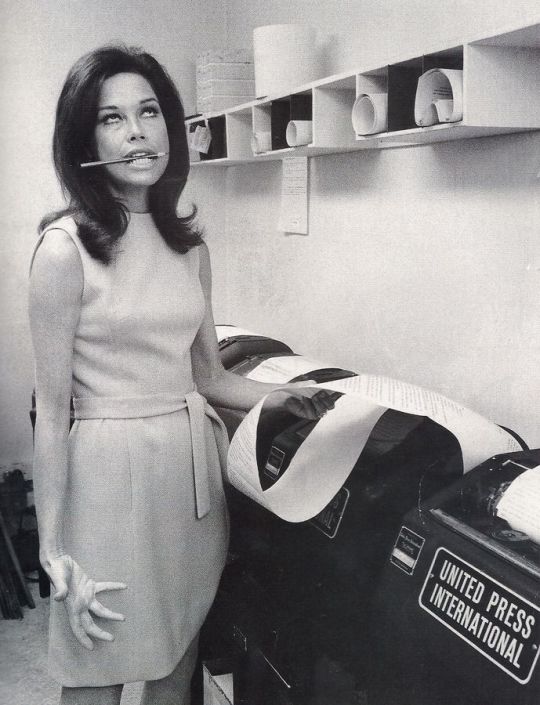

"I often lament that I am the last of the Moores. . . . But then I remember the image of the giddy pre-teen-age girl, waiting out in front of a theater to ask for my autograph, and the page from her scrapbook that featured a tattered picture of Laura Petrie alongside an homage to the then just departed grunge-rocker Kurt Cobain. I guess that's legacy enough for anyone." RIP Mary Tyler Moore

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

All My Christmas Writing in One Place

On being home for the holidays with my sisters, and the movie Sisters. (2016) On White Christmas and Black Lives Matter. (2014) On It’s a Wonderful Life and Occupy Wall Street-- especially relevant now that we’re all living in Pottersville. (2011) On Christmas in Connecticut-- “the guy teaches her vulnerability and she teaches him sex.” (2010)

#Christmas#xmas#Cloudland Revisited#White Christmas#Black Lives Matter#Sisters#It's a Wonderful Life#Occupy Wall Street#Pottersville#Christmas in Connecticut#vulnerability#sex#Jimmy Stewart#Barbara Stanwyck

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

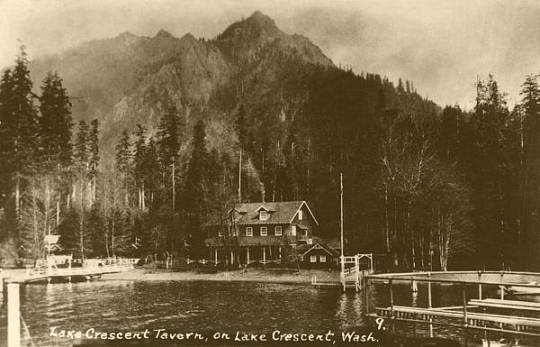

Lonesome Pine

I'm pining, pun intended, for an imaginary world in which I can teach at Yale and still see my sisters and Northwest forests whenever I miss them. No tsunamis yet please, no earthquakes, no volcanoes. I want the land of my youth, the land of my ancestors, full of old growth and orcas and oysters and otters and cherries and apples and wild rhododendrons. I want to live on an island in a foggy cabin with creaky warped floorboards and a chimney made of smooth stones. I want to to walk on a slippery kelpy gray-and-green cold beach. I want driftwood and mist and precipitous hills. I want to lift mine eyes unto the mountain from whence cometh my help. I want moss, I want mildew, I want mold, I want damp. I want a wet halo made of tiny raindrops. I want clouds above me and before me and shells and pine needles below me. I want to see glints of fish in the water. I want to cling to my home like a madrona against a cliff.

1 note

·

View note

Text

It’s Midsummer ritual time. Tonight I’ll light a bonfire in the mountains and make fervent wishes.

Midsummer

“As I lay in bed watching the sun climb out of the wheat field yesterday, I tried to remember all our Midsummer Eves, in their proper order. I got as far as the year it poured and we tried to light a fire under an umbrella. Then I drifted back to sleep again– the most beautiful, hazy, light sleep. I dreamt I was on Belmotte Tower at sunrise and all around me was a great golden lake, stretching as far as I could see. There was nothing of the castle left at all, but I didn’t mind in the least.” –Dodie Smith, I Capture the Castle (1948)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Waking up once more in a world full of stories.

Breakfast Reading

Breakfast reading is a raison d'être. It has to tip the balance between consciousness and unconsciousness, enough to make you not regret your choice to leave your bed. Telling yourself you have a job to do will get you up but won’t make you glad to be there; the right breakfast reading can make existence seem like a gift.

“Oh, this coming back to an empty house, Rupert thought, when he had seen her safely up to her door. People– though perhaps it was only women– seemed to make so much of it. As if life itself were not as empty as the house one was coming back to."

Barbara Pym is the PERFECT antidote to Marilynne Robinson. But in a minute I’m plunging into Robinson again like some kind of sauna plunge from steam to snow or vice versa. When I was a child I read books, and when I was no longer a child I kept reading them, and they have never failed me yet.

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Why are we reading, if not in hope of beauty laid bare, life heightened and its deepest mystery probed? Can the writer isolate and vivify all in experience that most deeply engages our intellects and our hearts? Can the writer renew our hope for literary forms? Why are we reading if not in hope that the writer will magnify and dramatize our days, will illuminate and inspire us with wisdom, courage, and the possibility of meaningfulness, and will press upon our minds the deepest mysteries, so that we may feel again their majesty and power? What do we ever know that is higher than that power which, from time to time, seizes our lives, and reveals us startlingly to ourselves as creatures set down here bewildered? Why does death so catch us by surprise, and why love? We still and always want waking.

Annie Dillard, The Writing Life (via lalevytexas)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Still my favorite take on the writing life.

Shirley You Can’t Be Serious

“The very nicest thing about being a writer is that you can afford to indulge yourself endlessly with oddness, and nobody can really do anything about it, so long as you keep writing and kind of using it up, as it were. All you have to do ― and watch this carefully, please ― is keep writing. So long as you write it away regularly nothing can really hurt you.” – Shirley Jackson, who died a half century ago today (quoted by VIDA) I am so unimpressed with recent critical takes on Jackson that are about assessing whether she is truly "great.” Whatever. She is uniquely odd, and that is my favorite kind of greatness.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Missing my sisters.

That Uncanny Feeling When Someone Else Writes the Story of Your Life

I WISH I HAD MORE SISTERS

by Brenda Shaughnessy

Keep reading

1 note

·

View note

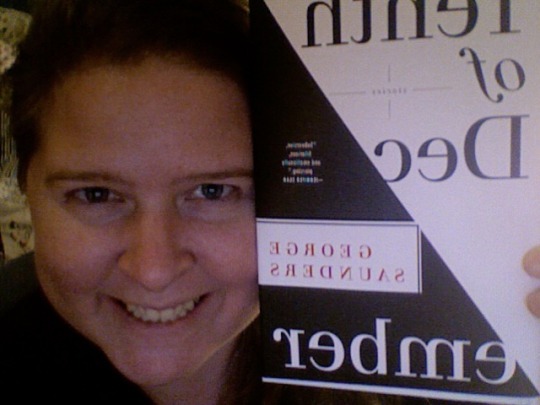

Photo

Happy Mother’s Day to George Saunders, whose stories nurture me; expose me; make me vulnerable; give me unasked-for advice; dissolve me into puddles of tears at unexpected and inconvenient moments; make me laugh until my stomach hurts; call me at odd hours to tell me things that might seem trivial but, when recalled days or weeks later, are revealed to have contained the meaning of life; in short, they mother me.

Mother’s Day has been a complicated holiday for me ever since my own mother died five years ago, and it has only grown more complicated as I have reached an age where it is looking more and more improbable that I will have children of my own. And today, as I so often do when melancholic, I pulled out what gives me comfort–a book of George Saunders’ stories. These stories not only taught me how to write; they taught me, and continue to teach me each time I reread them, how to be more human. Much like my mother did. So George Saunders, I bow to you in the deepest gratitude, and I thank you for offering me your heart on this difficult and challenging day. Please consider this my utterly inadequate Hallmark card to you.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Youtube Academic Survival Guide

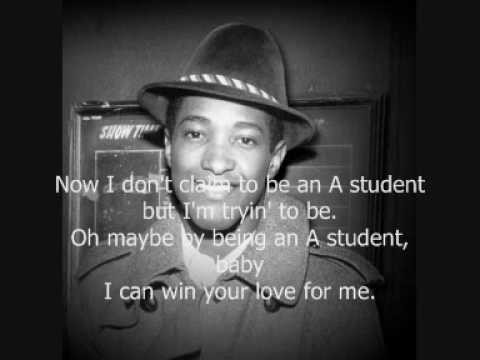

Useful links I send my students: For when you need a pep talk

For when you need perspective on grades and academic stuff

For when you’re doing your Daily Mirror Affirmations

For when procrastination has you down

For staying up late

For when it’s time to rest

458 notes

·

View notes

Text

Religious But Not Spiritual Sermon (Remix)

I preached this sermon at the University Church in Yale today. It’s a remix of a sermon I preached five years ago. I kept the long quote from my favorite MLK sermon, but added a lot more aching. *

These days,

More and more Americans are describing themselves as “spiritual but not religious.”

Have you heard this phrase?

Maybe some of you have friends or family who define themselves this way.

Maybe some of you define yourself this way.

“Spiritual but not religious” people have often had bad experiences with church,

or maybe they’ve never really had experiences with organized religion at all.

But they still feel connected to a divine spirit.

They experience spirituality

when they’re looking at a mountain or an ocean wave,

or when they’re listening to music

Or looking at art.

They feel a powerful sense of peace and purpose when they’re meditating,

or taking care of others,

or marching for a cause.

But their spiritual lives aren’t based on a sacred text like the Bible

Or a particular community of faith.

I have a lot of friends who are “spiritual but not religious,”

And I respect their experience, But I can’t really relate.

My own religious experience is very different.

I’m part of another category entirely.

This category also includes a lot of people,

And I suspect that it might include many of us here this morning.

It consists of people who are deeply connected to a religious community

And to the practice of faith,

But who often feel disconnected from spiritual experience

And supernatural belief. We love our church,

And we are deeply committed to Christian values

and to doing Christ’s work in the world.

But it’s hard for us to viscerally experience God’s presence,

and sometimes our faith doesn’t make sense to us.

When we pray, God often seems far away,

or even non-existent.

A lot of the time,

our emotional lives,

our intellectual lives,

and our religious practice feel disconnected. Our faith motivates us to care for each other

And to care for the world around us,

But often,

Like the disciples in the upper room,

We struggle to believe in Christ’s presence. At its worst, our faith can sometimes feel routine and automatic, Like clicking “I agree” on a software update.

We pass the peace of Christ in church every Sunday,

And we really mean it,

or at least we think we mean it.

But it’s hard for us to feel it.

To feel peace.

Whatever that means. And when we do stop to think about it, we start to doubt. In a world full of war and violence and hatred,

Why are we acting as if we can spread peace with a handshake

and a few words?

What are we even doing? But here we still are, passing the peace once again.

There’s a phrase sometimes used to describe people like this—

People like some of us.

We are “religious but not spiritual.”

We are people who keep the faith even when we’re not feeling it.

This is a sermon for those of us who sometimes feel religious but not spiritual.

It’s a sermon for those of us who doubt or disbelieve

But who keep showing up anyway.

Most of us would probably not choose doubt.

It can be hard to manage.

It can make us feel like failures or hypocrites.

It can make us feel numb and disconnected.

But the good news of today’s gospel is that doubt is not the opposite of faith.

Doubt can actually be an important part of the experience of being a disciple.

Thomas is the patron saint of doubters,

And the story of his strange encounter with the risen Christ

Has a lot to teach us about what it means to be Christians who doubt.

One of the most reassuring things we learn from Thomas’s story

Is that believing in the presence of Christ

in the absence of incontrovertible proof

has always been incredibly hard. It turns out that even if the risen Christ were standing right in front of us,

chatting with us and calling us by name, faith might still seem impossibly difficult.

We might still want more. And that’s OK.

Throughout the centuries,

Thomas has been criticized by Christians for his doubt,

As if doubt’s a bad thing.

But Jesus doesn’t condemn Thomas’s doubt.

He understands it.

He’s patient with it.

When Thomas says he needs tangible proof,

Jesus doesn’t say, “No you don’t!” Instead, he offers Thomas his wounds to touch.

Christ’s gracious response to Thomas teaches us

that we don’t need to feel guilty about how hard it is to believe without tangible proof,

Because it has never been easy.

My wonderful student Emily

is preaching on Thomas’s story tonight at the Episcopal Church at Yale,

And she shared this quotation with me from the great nature writer Aldo Leopold:

We can be ethical only in relation to something we can see,

feel, understand, love, or otherwise have faith in.

As we try to figure out the meaning of Jesus in our lives,

It’s natural to want to see and feel and understand and love.

And it’s understandably hard to figure out what it means to “otherwise have faith,”

here in New Haven in 2016,

since we can’t reach out and touch the nailholes in his hands. There will never be a completely satisfying solution to this problem.

We may always want more proof than we have.

We may always be prone to wander and waver.

That’s why Jesus addresses us in this passage.

We who doubt like Thomas did,

but who can’t just reach out and touch the wounds.

Jesus blesses us with a special blessing.

He says, “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe.”

When we are filled with doubt,

and still choose to follow Jesus,

we are blessed.

But we still have these unmet needs and cravings.

We still have desires to see and feel and understand.

The challenge is to know what to do with them.

How to keep them from eroding our hope.

What I’m about to say may seem strange and counter-intuitive,

But I believe it’s true: One of the greatest gifts doubt can give us, if we let it, Is the gift of constant chronic lifelong desire.

We are always going to ache a little at the absence of Christ.

I’ve felt that ache almost all my life.

So many days I’ve felt like Mary Magdalen by the tomb on Easter morning,

Facing a world without Jesus.

Like her I’ve wanted to cry out, They’ve taken my Lord away,

and I don’t know where to find him! I used to think that someday I would finally find the answers and assurance I craved.

But now I have a different approach to desire.

I tell myself,

Embrace the ache.

Christ gives us his Spirit to console us for the loss of his material presence.

And one way we can experience the Spirit

is to allow ourselves to open up to this experience of desire and loss.

Because to experience Christ’s spiritual presence today

is to acknowledge his material absence,

and to allow ourselves to always want more of him than we have.

The spiritual and religious life,

as we read about it in Scripture and throughout history,

It is not a life of static satisfaction or endless calm.

It’s a life of constant desire for more closeness with God.

It’s a life of continually seeking for more light,

more presence,

more truth,

more Christ.

The Psalmist asks, Why do you stand so far off, Lord?

Why do you hide your face in my time of need? How long will my soul be troubled? As the deer longs for the water,

so my soul longs after you.

My tears have been my food day and night.

My soul thirsts for you. When shall I be in your presence? Every day they say to me, Where is your God now? We often pray the Lord’s Prayer together in church,

The one Jesus prayed with his followers on the mountain. But when we’re alone, we sometimes pray another Lord’s Prayer, the prayer Jesus prayed when he was alone on the cross:

My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

As long as we’re alive,

we will never arrive,

and we’ll never attain all we crave.

But we can give ourselves over to a dire desire for God,

And in our desire we can glimpse God’s presence.

Doubt can deaden us if we let it. But doubt can also open us up to the experience of a strong, inexpressible yearning.

We shouldn’t ignore our unmet desire and we shouldn’t fear it.

We need to pay attention to it, and feel it, and follow it.

We need to let it lead us back to Christ’s table,

And out into the world

to see and tend to the wounds of Christ in the people who surround us.

In this yearning is our belief.

We might want belief to be an answer or a solution,

But the gospel of John reminds us that belief is also a process.

John tells us that these stories were written

That we may “come to believe that Jesus is the Messiah, The Son of God,

And that through believing we may have life in his name.”

“Come to believe” is an important phrase here.

For Thomas, the experience of Christ’s presence was instantaneous.

He reached out and he touched and he knew.

But for us, belief is not a simple one-time thing.

It’s more complicated than that.

Coming to belief takes time. Maybe years. Maybe the rest of our lives.

And when we listen to the stories of the gospel

And tell them over and over each Sunday,

We are not just reminding ourselves of what we already know.

Instead, we are actively participating in the process of belief.

We are coming to believe in Jesus,

Every day,

over and over,

we are coming.

Like the disciples who kept returning to the room where Jesus appeared, We keep coming back to the place where we can sometimes glimpse him.

I want to close with a story that’s not about Thomas.

It’s about another doubting Christian,

Someone who we might not think of as “religious but not spiritual,”

But who also struggled to feel the nearness of Christ.

It’s about Martin Luther King Jr.,

And it’s a story he told in one of my favorite sermons,

“A Knock at Midnight.”

King was a preacher’s kid,

and religion defined his life.

He grew up in the church,

and he always knew that he was destined to go to seminary

And get ordained and end up working in the family business,

his father’s church.

He had faith, and he had convictions,

but they were things he’d inherited.

They hadn’t yet become emotionally real to him.

He hadn’t yet experienced the sustaining presence of God.

But when he found himself heading up the Montgomery Bus Boycott,

And battling the mighty system of segregation,

He realized that his faith had taken him as far as it could go.

His family was getting constant hatemail and death threats.

The phone rang all day with anonymous callers who insulted his wife

and threatened their baby.

The fear of death pervaded every minute.

And the war against segregation wasn’t looking good.

The boycott’s enemies had the law on their side and their power was immense.

King was at a breaking point.

He couldn’t rest.

And one sleepless night he got up and went to the kitchen,

and heated up a cup of coffee,

and sat down at the kitchen table to pray.

In his despair he turned to Jesus,

The Jesus he couldn’t feel or sense or see.

Here is the story in his words.

I got to the point that I couldn’t take it any longer.

I was weak.

And I discovered then that religion had to become real to me,

and I had to know God for myself.

And I bowed down over that cup of coffee.

I never will forget it.

I prayed,

“Lord, I’m down here trying to do what’s right.

I think I’m right.

I think that the cause we represent is right.

But Lord I must confess that I’m weak right now.

I’m faltering.

I’m losing my courage.”

And it seemed at that moment that I could hear an inner voice saying to me,

“Martin, stand up for righteousness.

Stand up for justice.

Stand up for truth.

And lo I will be with you, even until the end of the world.”

I heard the voice of Jesus staying still to fight on.

He promised never to leave me,

Never to leave me alone.

No, never alone.

No, never alone.

In looking back on that moment, King said:

“I was weak. Religion HAD to become real to me.”

And this is what King’s story and Thomas’s story can mean to us:

It is in our weakness and in our doubt that Jesus comes to us.

We desperately need Jesus to be real,

And he can seem imaginary or far away.

But in our fear and our desire,

He comes to us and consoles us.

It is in these moments that our religion becomes real,

And the Spirit fills us with fire.

AMEN

4 notes

·

View notes