Text

Brieuc Poulain - Environmental Stakeholder Statement

As a young adult, graduating from the Paris Institute of Political Studies (Sciences Po), and as a future student of the Paris School of International Affairs in Environmental Policy, I define myself as a socially and environmentally responsible actor, both through my values and my personal commitment to the biotic community. As the grandson of a farmer who still believes in an ancient Breton Goddess, I am equally sensitive to how rural societies interacts with the environment in the political and cultural realms.

Therefore, I deeply relate to Aldo Leopold's Land ethic: « A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise. » My personal ethics is profoundly ecocentric. In my opinion, it is because we are part of the same community of living beings, or of the same biotic community, that we have duties to both its members and the community as a whole. Integrating human activities into the natural environment, could thus offer innovative models of behavior.

Furthermore, the intersecting perspectives of the natural and the social offered by the concepts of environmental racism and ecofeminism seem particularly relevant to the analysis of current public policies. De facto, it is by placing the question of environmental inequalities — the ecological harm that is done to certain category of the population, the poorest and the most discriminated — at the heart of its demands that the environmental movement will rise to the height of its historic mission, that of putting a stop to the destruction of our biosphere by a capitalist system generating even more inequalities. The critical theories mobilized throughout the semester thus confirmed my wish to pursue a career in the field of environmental governance.

0 notes

Text

Ecotheology

« Science and religion, with their distinctive approaches to understanding reality, can enter into an intense dialogue fruitful for both. »

Pope Francis, Enclyclical Letter, Laudato Si’, On Care For Our Common Home

Every day, media and scientists present new figures revealing the growing impact of Human Beings on our planet Earth. These informations inexorably add to the long procession of data accumulated over the last decades. The prospect of a global warming to 4 ° by 2100 and a massive erosion of biodiversity are their main recent signals. With the acceleration and combination of threats, our governments strive to respond mechanically with solutions that are usually devoid of environmental ethics, mainly technicists, supported by technology, engineering and other innovations in the commodification of nature, such as payments for environmental services.

The common denominator of these initiatives lies in their multi-secular anthropocentrism. They are driven by the same desire to preserve a nature, property of Man, by Man and for Man. And this, with the ultimate goal of maintaining an economic system that we know is largely responsible for the degradation of ecosystems.

Nonetheless, because man has no future in an exsanguine environment, what our reality henceforth demands and that our reason still cannot conceive or refuses to recognize appears more and more clearly. To guarantee our future, it is no longer just a matter of tempering the human impact on the living, with a great deal of innovation and sustainable development strategies in this or that sector. A true paradigm shift, the challenge is to found a new relationship with Nature and to establish a governance of the Earth.

This ambition requires first of all to break with the idea rooted in the West, particularly with Descartes, of the separation of Human Being from Nature. Over the centuries, it unfairly validated the hegemony of a human subject and exclusive owner of an object Nature, which he can freely dispose of beyond its limits and cycles. Convoked by this necessary philosophical and cultural transition, we must no longer think of ourselves as sovereigns but as accompanying and interdependent entities of the entire living world.

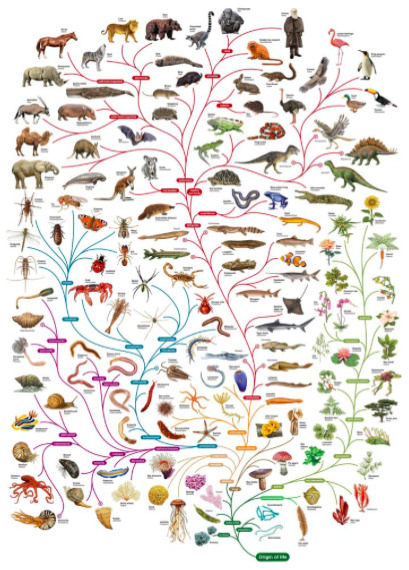

In this perspective, Human Being becomes a member of the Earth Community and the latter, and the ecosystems that compose it, are no longer considered as a collection of resources but a set of living organisms with interdependent functions and roles. By gradually adopting a more biocentric approach, we will be able to establish systemic rules no longer dictated solely by human reason but guided by the fundamental laws of Nature, a doctrine that the American eco-theologist Thomas Berry has theorized under the name of Earth Jurisprudence.

According to this philosophy, the Earth and the Universe are the primary sources of the natural laws that govern life. Earth Jurisprudence provides the philosophical basis for its governance. And this begins with our common pact. The social contract of Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau linking men to each other, excluding the Nature of the world, is transformed into a natural contract that binds human society to the natural world to which it belongs.

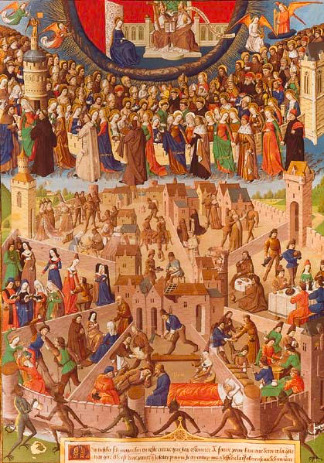

The climate issue in a globalized world has thus become a central issue. For Christianity, the climate issue is not a novelty but the way to approach it does not cease to change. From the Creation, the climate is closely linked to the divine plan. Between nostalgia for Paradise, moment of balance and harmony interrupted by the original sin, and fear of the Flood, expression of the divine wrath, the believer sought to trace a path that protects him and to make sense of the disturbances of nature. But in the course of socio-cultural changes, the reference to the religious evolves and the discourse follows, as evidenced by the encyclical Laudato si 'of Pope Francis (2015). The explanation by divine sanction gives way to the will to scientifically identify the causes and to contribute to a universal ethic in an ecological perspective. In this commitment, religion finds new energies.

In fact, it becomes difficult to present the Human Being as the center and summit of earthly creation, to whom everything on earth must be ordained, as Vatican Council II could still do. Biologists are, to say the least, reluctant to say that evolution is human- oriented, even though they may recognize that the human individual enjoys autonomy from his environment that is not shared by others animals. Moreover, if one realizes the perverse effects of human action, endangering the future of the planet, one feels little inclination to exalt humanity as the accomplishment of creation. Would it not be wiser to trust the earth, to learn more about the workings of nature, to listen to it and renounce all violence against it? Repeating stoic theses, it is asserted that nature, the earth in particular, would be a self-regulating system, according to, for example, The Gaia Hypothesis of James Lovelock.

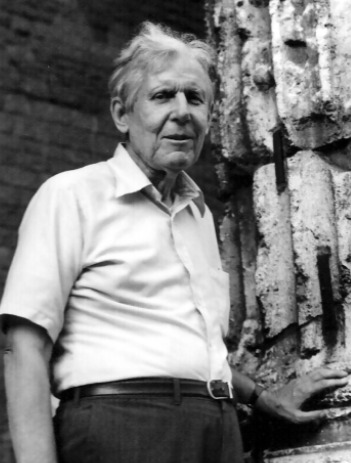

The teaching and writings of Thomas Berry inspired a renewal in the way that an entire generation sees the role of humanity in the planetary and cosmic community.

For Thomas Berry, the universe is « a communion of subjects and not a collection of object » and our first allegiance should not be to the human community, but to the biosphere as a unique but diverse « planetary community » with which we must move from a domineering relationship to a participatory relationship framed juridically and legally by explicit charters of rights covering minerals and plants as well as animals and humans.

Revealing of a continuous cosmogenesis, the physical sciences are for him a tool of introspection generating fascinosum and tremendum, two inseparable facets of spiritual experience. Far from invalidating the religious attitude or opposing it, science is for Thomas Berry a precious source of renewal of our obsolete cosmologies. He sees there a true and new Revelation. Threatened by the accelerated collapse of the branches of biodiversity on which we are seated, we are invited to consciously inaugurate the Ecozoic Era characterized by a global community whose emergence will have to go through a metamorphosis of the global village governed by the laws of industry and the market. The mission to which we are called to participate is for Thomas Berry a resacralization of the world and a celebration of our belonging to the living organism, polymorphous and without exclusion that must be the « community of the Earth ».

While sounding the alarm, Thomas Berry invites us to recover our role of depositories of the conscience and to start a true partnership with the planetary community. How can man rediscover himself in the image of God and how can he understand his vocation to the domination of Creation? Thomas Berry proposes to make the project of humanity that of the Earth, and thus that of the universe. That is to say to have a behavior compatible with the requirements of ecological balance.

The interreligious statement to world leaders was officially delivered to UN General Assembly President Mogens Lykketoft (right) on April 18, 2016.

After COP21 and before the signing of the Paris Agreement on Climate at the United Nations on April 22, 2016, international religious communities called on world leaders to take action on climate change by issuing a signed joint declaration by 270 senior religious leaders, 4970 people and 176 religious groups. « In our contemplation of how tragic moments of disintegration over the course of the centuries were followed by immensely creative moments of renewal, we receive our great hope for the future. To initiate and guide this next creative moment of the story of the Earth is the Great Work of the religions of the world as we move on into the future. » (Thomas Berry, “Religion in the Twenty-first Century,” in The Sacred Universe, 87).

Questions

In the United States, a country where the separation between church and state is still porous, a productive relationship between religion and politics may seem possible. In what extent does it apply to countries like France, where the separation of these entities is clearly inscribed in the collective imagination and the laws of the Republic?

Do religious leaders nowadays consider the ecology as a new, lucrative medium to conquer new believers?

Word Count : 1363

0 notes

Text

Biocentrism & Ecofeminism

The theorists of intrinsic value are in search of a general theory of moral value, of an abstract, universal principle, which qualifies individual entities. They do this by applying the Kantian schema of morality far beyond its usual limits: if I attribute to myself a moral value, because I am an end in itself, I must recognize the same value to any entity with the same characteristics. Once man has become aware of the profound identity of all beings, he will know how to respect and protect nature. These biocentric morals are morals of respect, moral ethics: in every living entity they discover an entity worthy of respect, by itself or in itself.

Among the authors who advocate a biocentric ethic, Paul W. Taylor occupies a special place, with his Ethics of Respect For Nature. According to Taylor, nature will not be well respected as long as humans continue to perceive it as a simple means. The intrinsic value is by no means an objective property, such as the form of the living being, which may give rise to an observation or investigation of a scientific nature. It is a philosophical notion, the adoption of which would give meaning to the idea of an obligation towards the living and natural world.[1]

To state that men have the obligation to respect living beings on the basis of the equality of all the living from the point of view of intrinsic value is to state a general moral principle. But in practice, the respect of this principle is not easy, because living beings do not have the same interests, which sometimes oppose them to each other. This is why Taylor has established rules for cases where respect for the life of one individual does not respect that of another. These rules are those of self-defense, proportionality, least evil, distributive justice and restitution justice. Thus, we must compensate for the loss, destruction, harm we have done to living beings, creating favorable conditions for the preservation of species, for example. This justice requires that respect for life be given a broader dimension: the community dimension. To emphasize the latter is to demand that not only the biotic communities be taken into consideration, but also all the natural conditions without which no species can survive.

We talked about community and nature. But can we talk about nature and community without talking about women? Karen J. Warren emphasizes the importance of feminism for environmental ethics. Furthermore, environmentalism is just as important for feminism: the cause of nature is integral to the cause of women. Karen J. Warren (born 1947), a feminist philosopher, has published numerous essays on ecofeminism. She has published two anthologies on ecological feminism, and lectured around the world on these issues.

When one approaches modernity, as Carolyn Merchant does, from the point of view of women, of nature, and of the least favored classes (since she associates scientific and technical development with that of capitalism), the notion loses its universal dimension: instead of progress and emancipation for all, we find the domineering ambitions of whites, straight, males. Women and nature find themselves on the wrong side of this conquering enterprise. By studying the transformation of the Earth's conception through metaphors that associate women and nature, Carolyn Merchant does not stick to the opposition of organicism and mechanism, often put forward by the philosophy of the environment (John Baird Callicott), she presents a real structure of domination: she uses the female experience to study nature, thus we discover that it is not only a question of representing it, but of dominating it, that it is a report of power, linked to affects and values. The criticism led by Carolyn Merchant is both epistemological and moral.[2]

From this joint and crossed dominance (nature is seen as a woman, women are assimilated to nature), Karen Warren analyzes the conceptual framework. In the series of dualisms that characterize modern thought (nature / culture, nature / society, woman / man, passive / active, object / subject, emotional / rational, matter / spirit), she sees the stages of a logic of domination that leads to subordination. Men, rational subjects, active, independent, are thus entitled to make women and nature the passive objects of their domination. Karen Warren calls for their commun release, at the end of all the oppressive 'isms': sexism, racism, naturism ...

« Le Rêve » (1910), Douanier Rousseau. MoMA, New York.

Far from the notion that the rapprochement between women and nature inevitably leads ecofeminists to naturalize women, the vast majority of ecofeminists have the opposite effect: it is rather the evidence of nature, as a given timeless and universal, which is in question. If we can consider, as feminists often do, that talking about nature and women is a way of doing violence to them, as the idea of nature is associated with domination (as understood by Karren Warren), conversely, to see in nature a woman is a way of devaluing her or asserting her dependence.

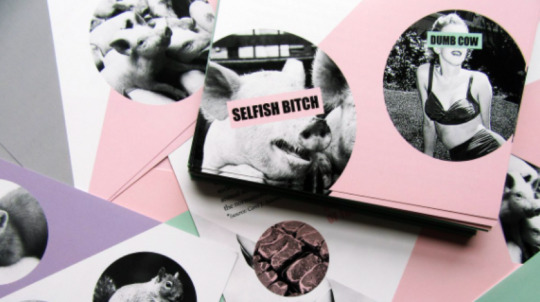

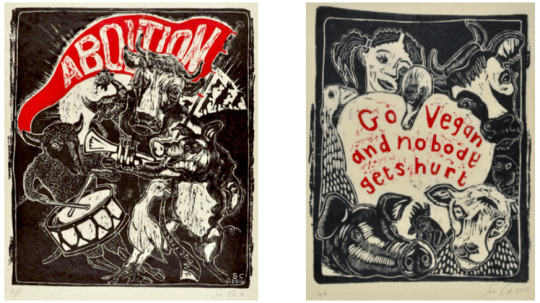

Front Page of FERAL - Feminists Rallying for Animal Liberation. Twitter, 2018.

In their fight against a logic of domination that applies to women as well as to nature, ecofeminists call for the adoption of new relations: non-hierarchical, non-domineering. This is where they refer to the ethics of care: « ecofeminism as a feminist and environmental ethic. ... of care, love, friendship, trust, and appropriate reciprocity — values that presuppose that our relationships to others are central to our understanding of who we are ».[3]

Questions

Is eco feminism intersectional?

What are the practical realities for restitution justice in a capitalist world?

Word count : 986

Bibliography

Taylor, Paul W. "The Ethics of Respect for Nature." Environmental Ethics 3, no. 3 (1981): 197-218. doi:10.5840/ enviroethics19813321.

Carolyn Merchant (2010) Earthcare: Women and the Environment, Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 23:5, 6-40, DOI: 10.1080/00139157.1981.9933143

Warren, Karen. 2000. Ecofeminist philosophy: a western perspective on what it is and why it matters. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield.

0 notes

Text

Hierarchical Animal Rights

« A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise. »[1]

Aldo Leopold

The values of integrity, stability and beauty are central to Leopold's ethics. Interpreter of this heritage, the American philosopher John Baird Callicott has unfolded its metaphysical and ethical foundations: the ecological vision require a rejection of a mechanical vision of the world, in favor of an organicist and holistic vision. This conviction leads him to develop a multilevel communitarian ethic, where belonging to each community entails a set of duties to protect the interests of the latter. Thus, the human being must make sure to preserve the interests of the human community, but as a member of a global biotic community, he must be careful to preserve its integrity, stability and beauty. To arbitrate the possible conflicts between the levels and the community memberships, Callicott advocates for a priority of the duties coming from the nearest communities.

He challenges, with a certain virulence, the supposed agreement and cohesion between environmental ethics and animal ethics. Rejecting the idea that we would have, on the one hand, animal or environmental ethics, not anthropocentric and, on the other, defenders of traditional conceptions for which there is only moral by, and for, Men, Callicott argues that the distance between environmental ethics and animal ethics is at least as great as that which distances each of them from traditional ethics (hence the image of the triangle). He thus accuses animal ethics of sticking to traditional moral conceptions, which they simply apply to animals. Callicott accuses these "humane ethics", which are animal ethics, to preserve "human values ».[2]

Indeed, one might think that environmental ethics simply pursue extension, crossing the threshold of sensitivity to extend moral consideration (as Paul Taylor does) to all living organisms (animals without sensitivity, plants, microorganisms). But that's what Callicott is questioning. The protection of nature, he points out, is less about individuals than about species or, more precisely, about populations.

In addition, it is not only a matter of worrying about the living, but also the environments without which they would not be able to live (the streams, the oceans, a marsh, a mountain, the air ...), and this especially since it is often the transformations of these habitats and of these natural properties that are at the root of the erosion of biological diversity. Finally, the protection of nature does not take into consideration discrete (even aggregated) entities, but a set of beings linked by interdependent relations and which form a whole: an ecosystem, or what Callicott, borrowing the term to Aldo Leopold, calls a « biotic community »[3].

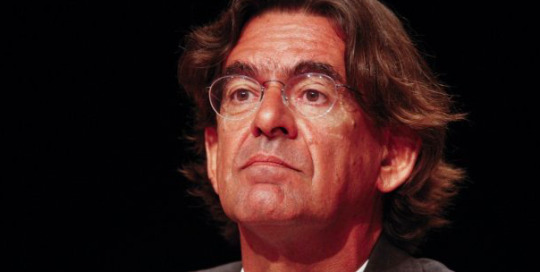

The major silence of French intellectuals with regard to ecology is not so much an indifference as a mistrust, even a declared hostility. According to Luc Ferry, the idea of the biotic community law is philosophically indefensible. He warns his readers, if not against a new form of irrationalism, at least against the virtualities of irrationalism of fundamental ecology. Thus, Ferry seeks to show how thoughts such as Callicott's ultimately lead to a hatred of man and a rejection of democracy: only an authoritarian regime could impose on men the necessary measures for the preservation of nature. As for the author, he defends an environmental ecology that recognizes man's duties towards nature and advocates progressive changes within the framework of liberal democracy that respects human rights[4].

Ferry is more interest in showing the dangers of deep ecology than about defending environmental ecology. His theses deserve to be specified. Still, it poses an essential question: Would it not be possible to refuse both "wild" capitalism and "deep" ecology in order to allow humanity to reconcile with nature without renouncing itself?

Luc Ferry has won the Prix Medicis for his essays, as well as the Prix Jean-Jacques Rousseau. He was formerly the Minister for Youth and Education in France.

Indeed, the ecocentrism of J. Baird Callicott raises many questions. Can we, as the author thinks, define our obligations towards the members of a community from a description of this community? It is a form of naturalism that not everyone is willing to accept. Moreover, what do we do when conflicts arise due to belonging to different communities? J. Baird Callicott believes that our allegiances to close communities take precedence over our allegiances to more distant communities. Still, in my opinion, a pluralist ethical theory is doomed to fail unless it produces precise rules for conflict resolution. Such rules are still lacking to J. Baird Callicott. D. VanDeVeer, tried to formulate some. His Two Factor Egalitarianism strives to achieve a maximalisation of utility. The first factor is the weight of the different interests, wether basic, serious or peripheral. The second relies on the degrees of sentience of the parties in conflict (based on the complexity of psychological capacities of the latter)[5].

Thus, after the liberation of animals, the elaboration of the details of our principles, procedures and moral practices would require that we put aside the "us / them" mentality that characterizes humanism, to develop instead a morality and a mentality oriented towards differences of degree which would emphasize our belonging to a fundamentally diverse community of interests.

Questions

What political project for a practical consideration of the ecosystem?

Is an ecological fascism conceivable?

Word Count: 963

Bibliography

Leopold, Aldo, 1886-1948. A Sand County Almanac, and Sketches Here and There. New York :Oxford University Press, 1949.

Callicott, J. Baird (1988) "Animal Liberation and Environmental Ethics: Back Together Again," Between the Species: Vol. 4: Iss. 3, Article 3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15368/bts.1988v4n3.1.

Leopold, Aldo, 1886-1948. A Sand County Almanac, and Sketches Here and There. New York :Oxford University Press, 1949.

Ferry, Luc. The New Ecological Order. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2009.

VanDeVeer, Donald, and Christine Pierce. The Environmental Ethics and Policy Book Philosophy, Ecology, Economics. Vancouver: Crane Library at UBC, 2012.

0 notes

Text

Egalitarian Animal Rights: Singer’s Utilitarian Approach

« All the arguments to prove man's superiority cannot shatter this hard fact: in suffering the animals are our equals. »[1]

Peter Singer, Animal Liberation

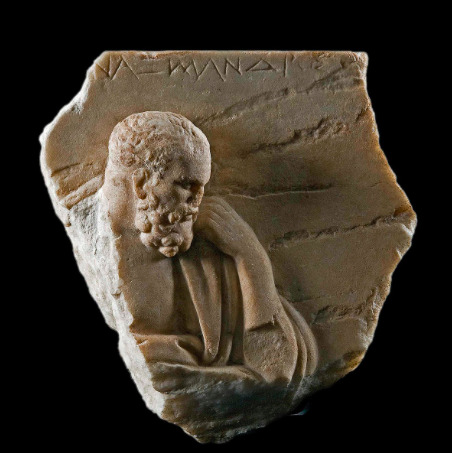

Do animals have rights? Legal rights, that is to say, granted, or moral rights, in an other word, inherent? The former fall under animal law, the latter under animal ethics. Both are related since legal rights are supposed to embody moral rights. This desire to assign rights to animals is ancient. Theophrastus, IV century BC, already wanted, according to the words reported by Porphyry, « to extend to animals the right »[2]. In 1864, Thomas Tryon, also attributed « natural rights » to animals, in the sense of a right to life and not to be enslaved[3]. The movement has since grown from a simple assertion that animals have rights to elaborate complex theories to justify it.

Tom Regan has quickly established himself as the leading theoretician of animal rights. The purpose of his theory of rights is to justify the abolition of animal exploitation. His major work,The Case for Animal Rights (1983), is one of the great classics of animal ethics.

The starting point of Regan's theory is the recognition of the mental life of certain animals, which can be said to have beliefs, a memory, a sense of the future, and a sense of self. Some animals, according to Regan, also have an intense emotional life, as Darwin had shown for the affection, fear, suspicion and jealousy of mammals.

Compassion is a decision. Not only can we believe ourselves charitable with animals without this being the case, but it comes down to thinking in their place. The Kantian idea of duty therefore becomes crucial. However, for Tom Regan, Kant's philosophy is questionable in that it continues to make animals « patients » and not genuine moral « agents ».

Regan distinguishes damage by infliction, such as physical or psychological suffering, and deprivation damage, which results from deprivation or loss of the benefits that make possible or expand the sources of satisfaction in life. This second category is precisely what allows the author to come out of a perspective based on the only suffering to say that the slaughter of the animals, even painless, is morally problematic, since « An untimely death is a depravation of quite fundamental and irreversible kind [...] Death is the ultimate harm because it is the ultimate loss - the loss of life itself. »[4]

Regan's damage principle therefore prohibits death. In this, he opposes the utilitarian theories which, by allowing harm to the extent that it increases the general utility, do not satisfy this direct duty not to hurt and could even lead to a legitimization of the murder, if not causing any harm to the survivors or if the harm caused was compensated by a superior benefit. The utilitarian, unlike the deontologist, does not give an inherent value to the beings. The interests of animals remain for this philosophy a « variable » of ours. This is precisely what Regan reproaches, he who conceives the inherent, intrinsic and categorical value in the Kantian sense of the term, because it admits of no degree.

« The fundamental wrong is the system that allows us to view animals as our resources, here for us — to be eaten, or surgically manipulated, or exploited for sport or money. »[5] Animal equality, according to Regan, is not one of their interests, but of their inherent value and respect for justice. He therefore poses the « principle of respect ». Expressed in terms of law, the principle of respect means that the subjects of a life have an « absolute right » to respectful treatment, that these animals have « a right identical to ours to be treated with respect »[6]. In other words, not to be used as the means of an end.

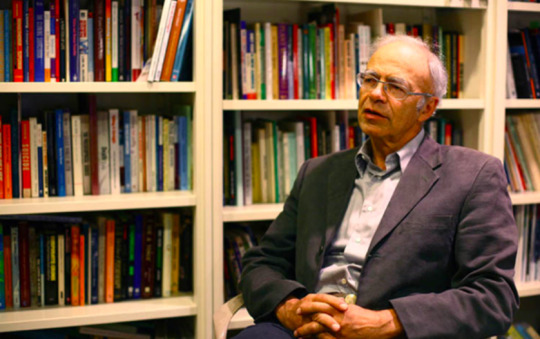

Philosopher Peter Singer. Source: New Philosopher, June 7, 2015.

Utilitarianism can be defined as the doctrine which impose usefulness as the principle of all values. From the writings of Bentham, we find in this philosophical current an attachment to the animal cause : « The question is not, Can they reason?, nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer? Why should the law refuse its protection to any sensitive being?»[7]. The maximalist version of this philosophy pushes for the overthrow of traditional values in the West. According to the proponents of this current, equality must reign between the animals, of which the man is a part. The animal, sensitive being, acquires rights which must be recognized to it: it must be able to defend them, if necessary before a judge. The animal thus becomes a potential subject of law.

Peter Singer, professor of bioethics at Princeton University, is the emblematic figure of the movement named after his famous book, Animal Liberation (1975). His point of departure is the thesis of animal equality. Equality, he explains, is a moral notion : it is normative.

Peter Singer considers that the moral horizon must be extended to animals. Indeed, animals are sensitive, especially to suffering, so it is immoral to make them knowingly suffer. For Singer, we must be guided by pity and not by our particular interests. Animals are just like us: living beings with a conscience. They therefore justify an equal level of consideration. It is by abuse of power that we deprive them of freedom, that we exploit them, that we kill them. The appropriation of domestic animals is an archaism in the same way as slavery and the domination of women by men, and it is certainly going in the direction of human progress to release, also and finally, animals of their chains. Killing animals and eating them is criminal, which is why Singer advocates vegetarianism. For Singer, the difference of species is not an acceptable moral criterion; what matters is sensitivity. There is a threshold of sensitivity according to the species beyond which the very notion of sensibility no longer makes sense; what makes the difference between a unicellular entity and a pig. The question of the level of consciousness is articulated with that of sensibility; what makes the difference between a human being, whose abilities to think and enjoy life are altered, and a pig in full possession of his means.

Questions

Are animals people or property? If they are neither, what are they exactly, and should not we create a new category?

What does our current disdain for animal pain says about human nature?

Word Count : 1103

Bibliography

Singer, Peter. Animal Liberation: The Definitive Classic of the Animal Movement. New York, NY: Ecco, An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers, 2009.

Porphyry, Thomas Taylor, Esmé Wynne-Tyson, and Porphyry. On Abstinence from Animal Food. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1965.

Tryon, Thomas. The Country-mans Companion, Or, A New Method of Ordering Horses & Sheep so as to Preserve Them Both from Diseases and Causalties, or to Recover Them If Fallen Ill: And Also to Render Them Much More Serviceable. London: Printed and Sold by Andrew Sowle. 1980.

Regan, Tom. The Case for Animal Rights. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Bentham, Jeremy. Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1967.

0 notes

Text

Egalitarian Animal Rights: Calculating Your Animal Suffering Footprint

« It is certain, in any case, that ignorance, allied with power, is the most ferocious enemy justice can have »[1]

James Baldwin, No Name in the Streets

« Ignorance is our species first line of defense. Yet, it is easy breached by anyone with the time and conviction to find out the truth. Ignorance has prevailed so long, only because people do not want to find out the truth »[2]

Shaun Monson, Earthlings

« And the reason for this ignorance is that a knowledge of the role these people played—and play —in American life would reveal more about America to Americans than Americans wish to know. »[3]

James Baldwin, Letter from a Region in My Mind

Differences of treatment based on arbitrary criteria prioritize individuals and allow some to enjoy privileges to the detriment of others. This construction of more or less privileged groups structures our society, which nevertheless claims the notion of equality. For a long time, however, people have contributed to revealing the social reality of the normative system and questioning its objective and universal appearances. Often through struggles for emancipation, they have undermined the axiom of the existence of a natural order, fundamental ideological support to discrimination and privileges that accompany them.

Anthropocentrism — the idea that humanity is the center and apogee of creation — derives from two systems of thought that reinforce each other: speciesism and carnism. Specism consists in granting less moral value to beings not belonging to the human species; Carnism, on the other hand, is the ideology which conditions us to consider as just, natural and necessary to eat, and more generally to subjugate, the members of certain animal species.The question of the moral status of animals, which is the raison d'être of animal ethics, therefore asks: are animals moral patients? Those who are engaged in the so-called animal liberation movement obviously answer in the affirmative and thus give animals, either to all or some of them, the quality of moral patient. As a consequence, whenever we, humans and moral agents, have a relationship with an animal who is also a moral patient, we have a responsibility to him and the way in which we treat him can be evaluated morally, characterized good, or bad.

The particular aspect that differentiates speciesism from racism and sexism lies in the fact that the difference in consideration and treatment of animals, in relation to humans, is a norm that is almost universally shared in our society. We live in a socially, institutionally and culturally speciesistic world. It is generally believed that speciesism is not discrimination like racism or sexism, because animals are really different. Unlike apartheid or segregation, which is no longer officially justifiable, both humans and animals are entitled to the treatment due to them, which differs according to their different nature. Thus, animals suffer from human beings a multitude of treatments. Whether they are produced for a particular purpose or taken from their environment, few escape the grip of the dominant species.

They are reproduced, fattened and killed on a scale never reached in history, cut up to be used as clothing or decorations, used to test weapons, pills or strippers, trained to attack or keep company, tamed to entertain in shows, captured to be visited in parks, fed, hunted, groomed, collected, mounted, for pleasure or profit[4]. The list is not exhaustive but sufficient to conclude that almost everything can be done to animals as long as they are not human. Indeed, men reserve for animals a fate that would be considered unacceptable and deeply unfair if it concerned human beings.

In a book suggesting that the industrialization of animal slaughter was the prelude to the Shoah, historian Charles Patterson presents the contemporary slaughterhouse as a scary, grimy and violent place[5]. In support of his argument, the author repeatedly quotes the work of the English artist Sue Coe. At the end of a multi-week survey in American slaughterhouses, the latter composed several painting representing it : cruel-faced men armed with whips, or even laughing men, killing beasts.

Small Factory Farm, 2010, from Sue Coe's book Cruel.

As for the other categories (gender for example), there is no logical link between biological differences and the reality of oppression, between justification and the act it is supposed to defend. The fundamental criteria that distinguish all human beings from all animals tell us nothing about the social dimension of the treatment we give them. This logic, similar to that found with racism and sexism, consists in hiding behind a veil of objectivity, a screen of a natural order, a reality that is only the result of power relations. There is no objective argument that justifies speciesism. We exploit and kill animals because we have the power.

In response to this institutionalized cruelty, the injunction to become vegan flourishes everywhere. It seems to be the universal rallying cry of the animal defenders. Such a position arouses the virulent disapproval of the food industry, but also, more surprisingly, some members of the animalist movement. They accuse the vegan lifestyle of losing sight of the fact that the refusal to eat eggs and fish or to wear leather is essentially a requirement of fundamental justice. Vegans would be pleased to find new plant-based meat replacements in stores, while billions of susceptible individuals continue to be exploited and killed. Veganism would only be a form of consumerism sprinkled with good conscience and self-satisfaction.

Go Vegan and nobody gets hurt, 2010, from Sue Coe's book Cruel.

All of these reflections, which use various means and reach sometimes conflicting conclusions, nevertheless share the same indignation at the violence suffered by animals. It remains to ensure that, in practical terms, this movement assumes all its consequences, so that the "animal question" is not only an intellectual posture but also a social awareness that changes the life of animals in the long term and make us better.

Questions

Are feminist, post-colonial and anti-speciesist struggles capable of a genuine intersectionality?

Veganism, at the crossroads between diet and social project, is it going to become the norm?

Word Count : 1099

Bibliography

Baldwin, James. No Name in the Street. New York: Vintage International, Vintage Books, 2007.

Monson, Shaun, Persia White, Moby, and Joaquin Phoenix. 2010. Earthlings. [Burbank, CA]: Earthlings.com.

Baldwin, James. Letter from a Region in My Mind. New York: Vintage International, Vintage Books, 2007.

Monson, Shaun, Persia White, Moby, and Joaquin Phoenix. 2010. Earthlings. [Burbank, CA]: Earthlings.com.

Patterson, Charles. Eternal Treblinka: Our Treatment of Animals and the Holocaust. New York: Lantern Books, 2002.

0 notes

Text

Leopold’s Land Ethic

In a book written at the end of his life, A Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold, in the American tradition of nature tales (of which Thoreau is the initiator), illustrates, following the months of the year, a series of vignettes, where he recounts his morning walks, in his area of Wisconsin (the Sand County)[1].

These lively and endearing stories lead to the presentation of an environmental ethic, which Aldo Leopold calls Land Ethic.

One of the most famous stories in the Almanac, Think Like a Mountain, captures its meaning. Leopold presents himself as a hunter, whom the howl of the wolf, on which he has just shot, snatches his certainty on the necessary disappearance of the wolves. In the course of this fable, Leopold criticizes the policy of extermination of pests decided by the US Wildlife Management Office, a policy in which he himself had begun to participate actively, and who had led to the disappearance of wolves in many American states. Extermination to the advantage of hunters, it was thought, but the outbreak of deer and fallow that followed was short-lived, resulting in ecological damage (overgrazing, degradation of slopes) of long duration. Thinking Like a Mountain depicts the situation and shows how the wolf has a place in this biotic community. The prosperity of herds depend on it in the long run. Leopold thus discovers the level that integrates the points of view, assigning each to its place: it is the mountain, which "knows" that, without the wolves, the deer will proliferate and will put its slopes at risk.

Unlike biocentrism, which emphasizes the intrinsic value of each living entity, Leopold's ethic emphasizes the interdependence of the elements and their common belonging to a whole, that of biotic community. This ethic defines the duties or obligations of belonging to an including totality.

They have no value in themselves, regardless of the place they occupy as a whole and which assigns their value. Man is not outside nature, he is part of it: he is a member, just like wolves or deer, of the biotic community.

Land ethic can appear as a redundancy of ecology. However, what ethics brings to ecology is a lived modality: it appeals to feelings. Exploring the conceptual basis of Land ethic, Callicott brings out all that is due to the theory of moral sentiments, that of Hume and Smith, whose Darwin can be considered as a continuer[2]. Belonging is felt as a feeling of brotherhood with other creatures, and all the progress of the Sand County Almanac is there to awaken our feelings of closeness to nature. As Leopold himself says, Land Ethic is « in fact a process a process in ecological evolution ». These feelings of closeness, belonging to other members of the biotic community, are a component of social behaviors. Land ethic can therefore be considered as a variant of evolutionary ethics: it is, says Leopold, « a kind of community instinct in the making ».

He thus attributes to the attention to the wilderness the status of path towards an inner transformation. In Sand County Almanac, he evokes attention to seasonal changes in the ecosystem, the migration of wild geese, and woodcock dances. Leopold is in line with the writer, naturalist and philosopher Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862). For the latter, who spent two years at the edge of Walden Pond, in the forests of Massachusetts, nature is the greatest resource of humanity; it is to be preserved so that the man can flourish[3]. Man is invited to become aware of the complex equilibriums of ecosystems and the interdependence of life, to change his perception of what surrounds him, to modify his relation to the ecosphere in which he lives.The author of The Last of the Mohicans, the novelist James Fenimore Cooper, gives the myth of the wilderness and the "American pastoral" the most popular expression: in contact with nature, a corrupt civilization is transformed, by many epiphanies, in a civilization that realizes the divine will on earth[4]. Emerson and John Muir are also examples of a true ecological conversion, a conversion to nature in the United States of America. The advent of modernity, however, has supplanted contemplation in favor of manufacturing. All these activities described by Richard Louv have the same symbolic and social significance: to recreate the link between the child and nature, a link that has been distended by urbanization.

Children fishing in my hometown. Carantec, France, 2017.

Today, the relation to nature becomes the place of elaboration of a discourse on the value of the individual, in what is subjective, emotional, in opposition to a model of individualisation dependent of a massification of modes of production and consumption. This transition from nature to the social, from the meaning to be given to the relations of men with nature but also of men between them is found in the generalization of the ecological metaphor to describe the functioning of social relations. Thus, it is crucial to re-introduce the experience and intimacy in our relationship to nature: « The power of this movement in that sense, that special place in our hearts, those woods where the bulldozers can not reach »[5].

Questions

Is not the plurispecificity nature of the Land Ethic reprehensible in that it does not give more importance to one species more than another?

Does the overall result desired by Leopold really take into account the value of individuals?

Word Count : 1003

Bibliography

Leopold, Aldo. A Sand County Almanac. London, Etc.: Oxford University Press, 1968.

Callicot, J. Baird. In Defense of the Land Ethic: Essays in Environmental Philosophy. Albany (NY): State University of New York Press, 1989.

Thoreau, Henry David. Walden. New York: F. Watts, 1967.

Cooper, James Fenimore. The Last of the Mohicans: A Narrative of 1757. London: Benediction Books, 2016.

Louv, Richard. "Last Child in the Woods - Children and Nature Movement - Richard Louv." Richard Louv Blog Full Posts Atom 10. Accessed March 19, 2018. http://richardlouv.com/books/last-child/children-nature-movement/.

0 notes

Text

Holistic Earth Wisdom Worldviews

« La Nature est un temple où de vivants piliers

Laissent parfois sortir de confuses paroles ;

L'homme y passe à travers des forêts de symboles

Qui l'observent avec des regards familiers.

Comme de longs échos qui de loin se confondent

Dans une ténébreuse et profonde unité,

Vaste comme la nuit et comme la clarté,

Les parfums, les couleurs et les sons se répondent.

II est des parfums frais comme des chairs d'enfants,

Doux comme les hautbois, verts comme les prairies,

- Et d'autres, corrompus, riches et triomphants,

Ayant l'expansion des choses infinies,

Comme l'ambre, le musc, le benjoin et l'encens,

Qui chantent les transports de l'esprit et des sens. »[1]

Charles Baudelaire, Correspondances

The sacralisation of nature presented by Baudelaire in his sonnet Correspondances resonates with certain discourses of our current era. Nevertheless, the sensible theme of nature as a mother figure and subject of law does not exclusively belong to the registers of poetry and mysticism. This profound reflexion is enriched by the work of thinkers such as A. Naess, the prose of precursors like H.D. Thoreau or naturalists such as A. Leopold. They all nourish powerful currents of ideas leading to ethical theses and legal solutions that I will try to present and discuss.

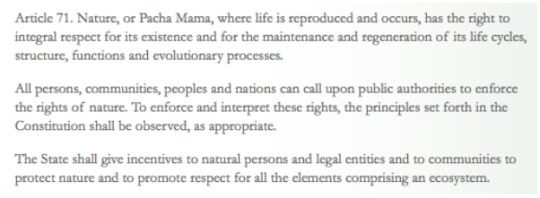

Nature has long been considered and treated as an object of exploitation. Nowadays, this legal entity has a dignity to assert and fundamental rights to oppose humans.

Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador, Chapter seven (Rights of nature), Article 71. Published in the Official Register, October 20, 2008.

Humanism proclaimed man the « measure of all things » (Protagoras), making our specie both the source of thought and value as well as their ultimate end. The revolution induced by deep ecology consists in reversing this perspective. The « measure of all things » is expanded to the whole universe (« widening the circle » is, indeed, one of the most constant slogans of the movement). Man becomes off-center and is placed in the line of evolution, in which he has no special privilege to assert. According to this philosophy, it is henceforth necessary to adopt the direct point of view of nature (« think like a mountain ») whose perfection of organization is the source of all rationality and all value. Its laws of cooperation, diversification and evolution are the model to follow. Each species, each site, each element, each process is now endowed with intrinsic value. A. Leopold gave, as early as 1949, a definitive formulation to this idea : « A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.»[2]

Thus, the distinction between what A. Naess named, in 1972, the shallow and the deep ecology is progressively endorsed. In his study of this dichotomy, Naess only has two lines to deal with shallow ecology: « Fight against pollution and resource depletion. Central objective: the health and affluence of people in the developed countries. »[3]

The essential reproach addressed to shallow ecology by deep ecologists is its continuity with the anthropocentric perspective: in short, nature would be protected only in the interests of humanity itself. One thing that would be of no interest to the men would be sacrificed at once. This is the fundamental flaw that affects all policies of resource conservation, limitation growth, as well as crusades for animal rights or the creation of natural parks. Moreover, these movements are criticized for concentrating too exclusively on legislative and administrative issues, and for expecting too much from rationalized management of natural resources, without understanding that a significant change can come only from a personal spiritual transformation : the progressive acquisition of the Earth wisdom. From this wisdom will emerge an ecological consciousness, an awareness of the non-separation of the self and the world.

These deep ecology authors most often do not take into account social recognition and the role of institutions in this process, but expect something from a change in epistemologies and ontologies. These discussions may be pursued further in specialized circles, but it seems doubtful whether real gains in environmental value recognition would be achieved in this way. As thought in the field of the environment, pragmatism seems a way to overcome such situations. These difficulties are based on both ontological and axiological categories, the theory of values here turning into ontological theory.

Luc Ferry, French philosopher, fervent critique of Deep Ecology Philosophy

Indeed, pragmatism claims that it is possible to proceed in other ways. We can find solutions on the basis of a theory of value that does not detach the latter from relations with the things of this world, nor from human and in particular communicational interactions. From a pragmatist point of view, we cannot remove the work of evaluation from an agent in any act of valorization or in any estimate of value.

De facto, environmental pragmatism tends to apprehend the world as a concrete reality, in its instability, its dynamics, its fluctuations, its transformations, of which humanity is fully involved. This confrontation with irreversibility appears contradictory with the notion of Cartesian doubt, the negation of the world of which it is a carrier. There is a realistic dimension of the environment that needs to be deepened. Thus, for Dewey, the organism cannot be considered independently of the environment in which it intervenes and that it controls, at least to a certain extent[4]. The idea of interaction is also at the heart of Mead's philosophical conception, in terms of the agency's interaction with the environment and the environment on the organism[5].

Far from rejecting the arguments in favor of the protection of nature that their anthropocentric origin would make them suspect, Andrew Light (like Norton and the other pragmatists) calls for all possible justifications, from the moment they are not compromised by intolerable commitments (fascist for example) and that they aim for the same end[6]. We must therefore not seek to convert to a pre-existing theory those who would be reluctant to this objective: it is necessary to find arguments that are admissible in their own moral conceptions and to enrich in this way the argumentation in favor of the environment.

Paul Gauguin (1848 - 1903) - Matamoe ou le Paysage aux paons.

Questions

Does pragmatism in environmental ethics has a genuinely common basis from which to begin a discussion about the policy to be adopted in the face of a particular issue?

Is a conciliation between the environmental ideals of the rich countries (discourse of the intrinsic value of nature) and the interests of the governments of developing countries (discourse more favorable to the economic approach — continuation of their development), feasible ?

Number of words : 1180

Bibliography

Baudelaire, Charles, and Théophile Gautier. Les fleurs du mal. Miami, FL: HardPress Publishing, 2013.

Leopold, Aldo, and Charles Walsh. Schwartz. A Sand county almanac and sketches here and there. London: OUP, 1968.

Naess, Arne. The Shallow and the Deep, Long Range Ecology Movements. Oslo: Inquiry. 1973

McDonald, H. P. John Dewey and Environmental Philosophy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2004.

Mead, George Herbert, Charles W. Morris, Daniel R. Huebner, and Hans Joas. Mind, self, and society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Light, Andrew, and Eric Katz. Environmental pragmatism. London: Routledge, 2005.

0 notes

Text

Planetary Management Worldviews and Stewardship Worldviews

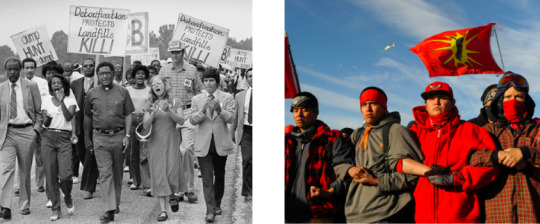

Figure 1. Protestors led by Reverend Joseph Lowery march against a proposed toxic waste dump in Warren County, North Carolina, in October 1982. Figure 2. Protesters block a highway during a protest in Mandan against plans to pass the Dakota Access pipeline near the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, in November 2016.

« Whether by conscious design or institutional neglect, communities of color in urban ghettos, in rural “poverty pockets”, or on economically impoverished Native-American reservations face some of the worst environmental devastation in the nation. »[1]

Dr. Robert Bullard

In 1982, the community of Afton in Warren County, North Carolina mobilized in civil disobedience actions against the dangers of polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB). This event was considered as the starting point of popular grassroots movements against the introduction of toxic deposits, the excessive use of pesticides, the contamination of air and water by industrial or mining sites. These struggles have revealed the extent to which these environmental risks primarily affect disadvantaged populations, whether for socio-economic or racial reasons. Afton residents were 84% African-Americans and Warren County was also particularly affected by poverty and unemployment[2]. The same is true of subsequent movements, which have sprung up in many places in the United States and have particularly affected Indian reserves, whose territories were threatened by various types of pollution or offered to mining. This is why such militant claims have been described as environmental justice. Driven by the civil rights movement, these struggles, developed in various parts of the United States, federated. In 1991, the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit was held in Washington and adopted 17 Principles of Environmental Justice.

From the local level where it appeared, the term environmental justice has also been used at the global level. Since its inception, the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) has sought to combine social equity with the protection of nature. Furthermore, the Convention on Biological Diversity adopted at the Rio Summit in 1992, after having, in its preamble, affirmed the « intrinsic value » of biological diversity, formulates, from Article 1, a requirement of justice: « the sustainable use of its components and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources »[3]. The Rio Declaration of 1992 commits nations to « conserve and sustainably use biological diversity for the benefit of present and future generations ». Thus, it introduces concern for future generations and links sustainable development to considerations of justice, making social equity its third pillar. In these global concerns, climate change has received particular attention, and the issue of climate justice has been aimed at studying the principles of equity that can govern the proper distribution, between different nations or between nations’ individuals, of the overall burden of climate change and the risks it implies (The Paris Agreement).

Questions about environmental justice, while referring to existing philosophies of justice, tend to question them or reveal their limits : Can we extend the boundaries of justice to include non- humans when it comes to environmental issues? What duties can we have regarding humans who do not exist yet and whose very existence may depend on the decisions we make now? What does it mean to limit environmental justice to the national or state framework? At what scale should the principles of environmental justice be defined ?

Recognition of the people is a prerequisite for obtaining justice. It is the basis of the opportunity to express not only his opinion but also and especially to see his opinion taken into account. In the Love Canal case, women who tried to express their point of view and report their testimony were systematically ignored, discredited because they were considered irrational, emotional and uninformed[4]. Women and people of colors are systematically denigrated by the authorities because they are considered irrational and uninformed. This is a problem all the more crucial since minority populations are historically not present in environmental movements. They could therefore not gain credibility by this means. Movements for environmental justice provide a voice for these populations. They contribute to giving them a political weight, to foster their empowerment by insisting on their recognition. Eniko Horvath, journalist for the Environmental News Network, notably reported the opinion of Mary Robinson on the matter. The former United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights recognizes that a human rights focus would strengthen the Paris climate deal[5]. Associating these two thematics clearly would allow environmental justice champions to push for bolder actions within their companies and deliver stronger benefits for the most vulnerable.

Environmental justice is not based on a single, consensual definition. One of its main concerns is the extent of the duties of each generation towards individuals who will live in the future. Two contemporary theories of justice, utilitarianism and liberalism, advocate the idea of an intergenerational saving: it is not enough to preserve the common heritage, transmitted by past generations to meet our obligations, but it is necessary to transmit an improved world. The reasons given to justify such an intergenerational saving are different. For utilitarians, it is required to maximize welfare or utility in society, while for liberals, and especially for John Rawls, saving is considered necessary to form the basic institutions of society and therefore allow everyone to be free[6]. Indeed, building a fairer world makes it possible to limit the weight of social and geographical origin for the next generations, injustice linked to birth, and thus to reduce the transmission of inequalities over time.

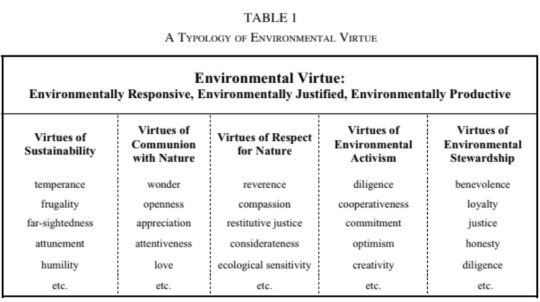

According to Aristotle, a social institution is right if it pursues objectives that promote the role of virtues[7]. It must allow to cultivate the good characters and to train good citizens. Ronald Sandler proposes to assign as origin to the environmental virtues, not their relation to external goods, but the very constitution of the moral subject: he defines this approach as substantial[8]. He supports the idea that beings who have a property of their own at the same time have an inherent value. Individual living organisms and certain collective beings that make up the environment have a property of their own. The willingness to recognize the inherent value of certain natural beings has a normative or motivational force in the sense of respect, solicitude, compassion and justice, and is an essential trait in the portrayal of virtuous individuals. The ethics of virtue remind us that in terms of the environment, the members of abundant societies do not even live decently: in this respect, their critical dimension is undeniable.

Questions

The question of environmental justice is now becoming that of the distribution of environmental policy burdens. How can we measure the environmental debt of the countries of the North towards the countries of the South?

Is the ratification of an international and binding legislation on the status and rights of climate change refugees feasible ?

Word Number : 1321

Bibliography

"Learn About Environmental Justice." EPA. February 27, 2018. Accessed March 05, 2018. https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice/learn-about-environmental-justice.

McQuaid, Times-Picayune John. "Change in the air." NOLA.com. August 12, 2016. Accessed March 05, 2018. http:// www.nola.com/politics/index.ssf/2000/05/change_in_the_air.html#incart_river_index_topics.

Convention on Biological Diversity ; Convention on Climate Change ; Forest Principles ; Rio Declaration. S.l.: United Nations Conference on Environment & Development, 1992.

McQuaid, Times-Picayune John. "Change in the air." NOLA.com. August 12, 2016. Accessed March 05, 2018. http:// www.nola.com/politics/index.ssf/2000/05/change_in_the_air.html#incart_river_index_topics.

Horvath, Eniko. "Climate Change and Human Rights." Environmental News Network. May 22, 2015. Accessed March 07, 2018. https://www.enn.com/articles/48589-climate-change-and-human-rights.

Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice. New Delhi: Universal Law Publishing Co Ltd, 2013.

Aristotle, and W. D. Ross. The Nicomachean ethics. Los Angeles, CA: Enhanced Media Publishing, 2017.

Sandler, Ronald L. Environmental ethics: theory in practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

0 notes

Text

Planetary Management Worldviews and Stewardship Worldviews

As a direct heir and a natural extension of Judeo-Christian thought, modernity envisages the salvation of humanity in the progress of science and technology. However, this progress is defined as the continuous growth of the domination of men over nature. An emblematic figure of this dichotomous vision, which strictly separates the human being from the nature and which assigns to the first the ambition and the duty to enslave the second, is that of Francis Bacon, who writes in the Novum Organum (aphorism 129) that science’s ultimate goal is to « to establish and extend the power and dominion of the human race itself over the universe »[1]. Rene Descartes conceptualizes this radical distinction between man and nature through the metaphysical basis of his theory of substances, distinguishing the thinking substance, specific to man, from the extended substance, simple material that the thought must informe. For the philosopher, the ultimate goal of human development, through scientific and technical progress, would be to « render ourselves the lords and possessors of nature »[2].

The role of master and conqueror conferred to the human being in Judeo-Christian thought and his secularization through the modernist faith in the human power of domesticating nature are the conceptual roots of the Western development model. While protection of nature has long been associated with a concern for the benefits that human societies derive from it, we are now seeing more and more exclusive attention to these benefits, both in scientific research and in public policies dedicated to biodiversity conversation. It is therefore necessary to question the effects of such an inflection.

Is it essentially a change of vocabulary and rhetoric with little effect on reality or is there a real transformation of logic and object? Do conservation of biodiversity and protection of ecosystem services refer to convergent and potentially interchangeable objectives, or is the shift to a service logic likely to undermine the necessary commitments to biodiversity?

In the ecosystem services approach, nature is considered only by the benefits that people derive from it. Therefore, we shall describe a shift from a biodiversity-centered perspective to a perspective centered on ecosystem services, as the effective instrumentalization of nature. This paradigm shift confirms the idea that the value of natural entities would only be relevant to their utility, direct or indirect, for human beings.

« From the fact that there is no normative definition of the natural state, it follows that there is no normative definition of clean air or pure water — hence no definition of polluted air — except by reference to the needs of man. »[3]

In People or Penguins: The Case for Optimal Pollution, published in 1974, Baxter discusses the relationship between the use of resources as a necessity for survival and pollution. According to him, no human community can present itself as non-polluting. Thus, according to him, pollution must be accepted, despite its harmful effects on the environment, provided that it increases the happiness of the majority of the human population. Baxter is the archetype of the utilitarian anthropocentric. Its main proposal is as follows: in order to solve the environmental crisis, we should not aim to obtain clean air or quality water but rather set ourselves an optimal level of pollution.

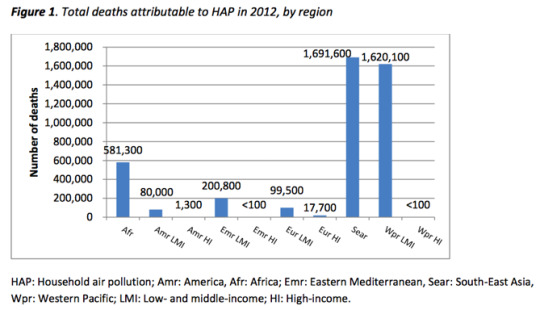

The relative preservation of our environment is not a problem since humans are highly dependent on nature, it is thus in their interest to preserve it. Baxter rejects any value to the natural world regardless of human interests. Its ethics does not exclude private altruism, but it rejects the possibility of harming humans to ensure the well-being of nature, the measure of this being the equilibrium point named the optimal level of pollution. Yet, the World Health Organization estimates that 4.6 million people die each year from directly attributable causes to air pollution. The investment in the fight against the latter is a public health issue, insinuating that this money could be better used in the construction of hospitals is therefore a mistake on the part of Baxter. The decline in mortality is, de facto, a direct return from investment in environmental protection.

Given the imperative of economic development that characterizes the contemporary world, economic efficiency is often considered as a determining factor in private practices as well as in public policies. As a result, many researchers and conservationists have considered that the most compelling way to advocate for the protection of biodiversity is not only to highlight its contribution to human well-being, but also to demonstrate economic interest. These attempts then operate a second reduction. After having reduced nature to its instrumental values, it is a matter of quantifying these values in monetary terms. The instrumentalist reduction is then coupled with an economic reduction. If there are rights and duties only between men, how can we feel obliged to protect our environment?

If the human being and the natural environment are interdependent and require to be respected both, the limits of strongly anthropocentric positions are apparent, and a certain porosity between anthropo, patho, bio and ecocentric positions exists, especially in the practical domain concerning public policies and individual and collective action: the fight against pollution, a reforestation program or the preservation of spaces can be implemented both in the name of an anthropocentrism concerned with future generations and a bio or ecocentrism defending respect for endangered species and ecosystems. It is in this sense that some authors, such as Bryan Norton (1984), advocate a pragmatic approach that allows people with different postures — himself claiming a weak anthropocentrism — to work on the same practical issues.

Based on the common sense argument that the instrumentalization of nature does not necessarily lead to the destruction of it, a whole pragmatic reflection has developed, that challenges the desire to base environmental ethics purely on intrinsic value. It is accused of using heavy metaphysics and leading to sectarian positions. The quest for intrinsic value can be seen as the search for a unique, monistic theory of value. It is all the less likely to be accepted by as many people as it implies a metaphysical questioning, a search for the foundation. To this monistic and solitary vision of value, pragmatists oppose a pluralistic and relational vision. Why, to affirm the value of a forest, should one stick to one's "intrinsic value »? For example, according to Bryan Norton, a weak anthropocentrism based on thoughtful and not merely felt preferences is sufficient to warrant the protection of wilderness as a moral resource. For him, the individualism / non-individualism dichotomy is more decisive for the foundation of environmental ethics than that which is played out between anthropocentrism / non-anthropocentrism, since « no successful environnent ethic can be derived from an individualistic basis, wether the individuals in question are human or nonhuman.»

Bryan G. Norton, School of Public Policy at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Norton's writings testify his willingness to challenge the practical relevance of all of this speculative problem in the name of two types of arguments intimately linked to one another, arguing, on the one hand, the disastrous effects internal quarrels between environmental ethicists that makes their speech politically inaudible and paralyzes their concerted action and, on the other hand, the particularly sterile nature of these debates insofar as the major concept of human interest is left in a state of extreme indeterminacy. We thus come to no longer be able to distinguish between a utility which is satisfied in the immediate consumption of the goods of nature (raw materials, agricultural products, etc.), and a utility which supposes the preservation of the useful object as a whole, as conservation is a condition for the satisfaction of human interests

Norton's opinion on this point is that nature protection programs are perfectly justifiable from the point of view of a sufficiently broad conception of the anthropocentric instrumental value. Better still, it is important to recognize this environmental problem as an undeniable practical superiority for at least two reasons. On the one hand, the invocation of the anthropocentric instrumental value corresponds, in fact, to the most widespread mode of justification among environmentalists, and constitutes in this respect an immediately common space for interlocution within which debate can take place. On the other hand, by succeeding in neutralizing the axiological controversy between intrinsic value and human utility, the use of the anthropocentric value in the broad sense allows, in this way, to leave to the subjectivity of each one the choice in favor of different philosophical options, and thus to shift the debate on the ground of the rational modalities of environmental action.

In reference to these pragmatist and pluralistic options, Norton has striven to develop its own theory of sustainable ecosystem management. Norton considers that the problem of the morally acceptable conditions of sustainable development needs to be posed within the framework of a theory of intergenerational justice. He also believes that the differences between the currently available models of sustainability come essentially from the way in which the problem of determining the obligations incumbent upon the future generations is posited, and how it is solved.

The difficulties encountered in attempting to overcome the usual limits of morality to include all living beings or the biotic community, explain that attempts have been made to develop an environmental ethic by challenging the rigidity of the distinction between intrinsic and instrumental value. It is not necessary to contrast the intrinsic value with the instrumental value, it is enough to show the diversity of the instrumental values. Utility is not only immediate, or material, it must be taken into consideration that there is a future, and future generations, that there are selfless interests, as are aesthetic or cognitive interests. To consider nature as a set of resources is not necessarily to destroy it: nature no doubt supplies us with goods (raw materials, agricultural products, etc.) that we consume by destroying them, but it also provides services (pollination, recycling, nitrate fixation, homeostatic regulation), without which we would not have access to these goods, and that it is in our interest to keep in activity, in no way to make disappear. The same thing can be said of the cognitive or aesthetic interest for nature.

If scientists, like systematicians, need hardly any elaborate environmental ethics, it is because in defending nature, they defend their object of work. In the same way, those who admire the beauty of nature, or find in the sublime a spiritual experience that elevates their soul, undoubtedly value a subjective experience of their own, but in doing so, they need a natural untouched without which this experience could not take place. Nature conservation programs are perfectly justifiable from an anthropocentric point of view, and one can, as Bryan Norton does, feel that this is the most common form of justification for environmentalists. Reductive anthropocentrism denounced by ecocentric ethics, one can thus distinguish an expanded anthropocentrism (sometimes called "weak") such that to value the man does not necessarily imply to devalue the nature.

The notion of ecosystem services reinforces and generalizes an anthropocentric posture that should nevertheless be questioned. In my opinion, economic evaluations of these services reduce the diversity and complexity of human values to the single market metric. Indeed, the commercialization of nature accentuates the injustices produced by the neoliberal logics of exchange based on individual property, markets and financialization. At the moment when the demonstration of the failure of a system becomes irrefutable, everything happens as if the environmental question could be integrated into this system without fundamentally calling it into question, being content to make development sustainable and the capitalist economy « green ». It is certainly a great threat to nature, but it is also and certainly more for human societies.

Questions

By reinstalling man as the center of values, pragmatists do not abandon the concern for nature. But do not they turn away from what can be considered as the main teaching of non-anthropocentric ethics: we are not alone in the world, non-humans also count, for themselves?

Pragmatism: ecological awareness or capitalist stratagem? (cf. conclusion)

Word Count : 2019

Bibliography

Bacon, Francis, and Joseph Devey. Novum Organum. New York: P.F. Collier, 1902.

Descartes, René. A Discourse on Method. North Charleston, SC: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2016.

Baxter, William F. People or penguins: the case for optimal pollution. New York: Columbia University Press, 1974.

Norton, Bryan. "Environmental Ethics and Weak Anthropocentrism." Environmental Ethics 6, no. 2 (July 1984).

0 notes

Text

Methods Used in Environmental Philosophy and Ethics

The ethical and political presupposition of modernity is that nature is external to humans. Human beings regard it as their environment, as if things of nature were designed for the sole purpose of serving them. This is the origin of the ecological crisis of our time: the political and technical project of enslaving a fantasized nature dedicated to satisfying our needs. As for its valorization, it is reduced to the capitalist commodification of its resources. Our modern State and Being are therefore the results of an alleged right to organize the struggle against nature rather than a life in harmony with the latter. We must disqualify the political and moral foundations of our ways of thinking and acting, and replace natural law with a biotic law allowing a radical reform of the relationship between the city of men and nature[1]. De facto, the crisis is not ecological but political: it is that of the essential foundations of the city as πόλις / pólis.

To what extent can environmental ethics revolutionize our anthropocene modernity? What are our duties towards future generations?

If thinking in terms of ecological footprint allows us to emphasize that our way of life is unsustainable — not sustainable ecologically and morally unjustifiable — it does not shed light on the aporia mentioned above. In particular, this does not explain why a reasonable being — the Homo sapiens — tends to live less and less in reasonable ways. We are utterly unable to articulate rationally our conduct and our knowledge. This lack is specifically modern, all traditional societies had the capacity to articulate in a κόσμος / kósmos their representations of nature and their moral rules[2]. We have lost this capacity from the moment when things have become morally neutral objects, ontologically distinct from the moral subjects that we are. This dualism has resulted in what Heidegger has denounced as an alienating loss[3]. Such duality negates the sine qua non condition of an environmental ethic. Indeed, moral rules can only apply to self-conscious subjects. We cannot reasonably expect them to be applied to objects, nor even as to the relations of subjects with objects.

In the search for intrinsic value, two environmental ethics emerged. The first considers that every living entity, whatever it may be, deploys, in order to maintain itself in existence and to reproduce itself, complex strategies: it instrumentalizes its environment for its own benefit, and as such, deserves respect. As this ethics gives moral value to every living entity, it is said to be biocentric. The second considers that it is because we are part of the same community of living beings, or of the same biotic community, that we have duties as much towards its members as of the community as a whole. It is called ecocentric. It finds its roots in the reflection recorded by the American forester, Aldo Leopold. He exposes his Land Ethic, and formulates it as such: « A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise »[4].

Violence against animals is a source of increasing moral concern. This ethical concern is not recent, it has been questioning philosophers since Antiquity. Nevertheless, the evolution of the legal status of the animal is the surest sign of a change in mentalities. The Old Testament evokes in particular the community of destiny that brings together, as mortals, men and animals. The biblical text also includes a number of prescriptions protecting working animals. But it is Greek thought that formulates this problem in truly moral terms. In fact, Pythagoreanism and Orphism condemn sacrifice and advocate vegetarianism. Moreover, the skeptical tradition seeks to reduce the distance between man and animals, by emphasizing their ability to reason. Porphyry, in his treatise On abstinence from animal food, elaborates a critique of the arguments justifying the animal sacrifices. We find this theme with Plutarch, especially in his On the eating of flesh, where the refusal of foods from the killing is appreciated for moral reasons. In That Brute Beasts Have Use of Reason, Plutarch asks the major question: must one be endowed with reason to be recognized a moral status?

The French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 - 1778)

The moral question takes, with the philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a crucial turn thanks to the concept of pity, this ability to identify with every suffering being, whether human or animate[5]. By placing sensibility at the source of natural rights, it includes all beings that may suffer in the moral community. Since animals are beings capable of feeling pleasure and pain, inflicting pain on them is not a morally neutral act. Whatever the limits and derogations that some wish to oppose to this principle, any honest and worthy reflection will lead to the conclusion that it is not indifferent to inflict suffering.