Text

Dosier annotation

I took an intuitive approach with this assignment. I regret this a little bit now, because looking at everything all together, it feels like I just complained a lot. It is a mixed bag of books, films and exhibitions I have seen for fun and research. (Although the line between the two has blurred.) In a more pragmatic tone, I approached this to solve a series of problems, and so I looked at different artists who are good at tackling similar types of problems. A minimum requirement of a selection is that I like it, but I've found that my entries almost always circle back to (1) affect, (2) being poetic, and (3) the legacies of World War II and/or the postwar era.

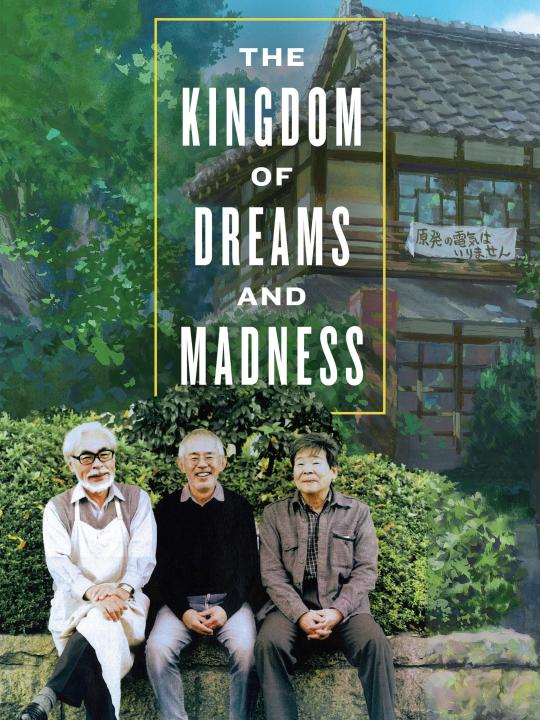

First: I looked at Miyazaki for his work's affective qualities. He does this so well, and this most likely owes to his process of working out the stories of his films based on how he feels, and translates this to how he wants the audience to feel. In The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, it is revealed that he does not ever write a script. He storyboards directly, and it takes about a year to finish. What’s more astounding is that even before he completes storyboarding, his team already starts animating. The production crew doesn't know how the film will end until their animation catches up. This organic, intuitive, wild card approach is felt when you watch his films. The narrative feels almost non-linear, propelled by emotion through sumptuous visuals and sweeping scores. In the documentary, Miyazaki is established as a notorious perfectionist. This careful and laborious orchestration to achieve such affect is what I'm striving for in my own practice.

Second: On being poetic (and even cheeky): Nguyen and Parker had this quality in their practices. Both can hold their audiences in such a charismatic manner. They touch on their own lived experiences and the politics that surrounds them in a sentimental but gripping way, without being indulgent and sappy. Suh, who by now I probably have a one-sided love-hate relationship with, also does this, albeit in a quieter form.

I am drawn to the approaches of these artists since my sculptural installation practice needs to oscillate between the personal and the public. Recently, my works have become a form of psychoanalysis. I have been having to conduct a psychological enquiry within myself but also bearing the responsibility to contextualise my experiences. The direction of enquiry goes inward before having to go outward. The private has to go public, otherwise, does it even matter? My practice cannot exist in a bubble. Installation art also demands embodied viewers.

Third: My gravitation towards the second world war and the postwar owes to how recent it has been and the legacies that are very much felt today and even dictate my life. Filipinos are still reeling from centuries of colonialism, and my practice is at a point where psychoanalysis is shifting into a form of mental decolonisation. Looking at Snare for birds, research and enquiry is an ongoing decolonisation, piecing together our fractured histories and identities, and taking control of our narratives. While my artworks don't necessarily engage with archives, the struggle and need to find what we once thought was lost is necessary to imagine how we can possibly move forward, with better ownership and understanding of ourselves.

0 notes

Text

Chó bò

Chó bò is the approximate Vietnamese homonym for ~ trouble. Bluntly translated, chó bò is a ~ dog cow or ~ dog crawl. This linguistic joke for many Vietnamese people learning English represents a capacity to make trouble.

This PhD thesis comprises original research and artistic work made with my family. As people from the Vietnamese diaspora, our experiences are formed by dispersals and estrangements as settler-colonisers on this continent. Our daily encounters in the realms on which this thesis is focused—contemporary art, academia, and family enterprise—are folded into distinct systems of colonial power and violence.

I often make work with my family in video-performance and the documentary form. Our inter-generational, political, and language differences add to the conceptual complexity of what it means to collaborate, make art, produce archives, and confront our position as displaced people. This thesis aims to address how our artistic collaborations utilise linguistic and archival approaches to articulate the systemic racism we encounter as people from a refugee background, but who are also embroiled in the colonial infrastructures of our new home.

Aligning with thinkers such as Gloria Anzaldúa and her critique of coloniality, to Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Hito Steyerl on minoritarian forms of translation, and to Sara Ahmed on racism in the university, this thesis describes how collaborations with my family can trouble the contradictions of colonial violence within our relationships.

Reconnecting with individual members of my family through art, I have gained a better understanding of my language and culture; I have also found important artistic and political connection with peers. Collaborating with my family has forced me to rub against the researcher-research subject binary, the archival visibility of being invisible, the rhetoric of institutional inclusion, and the weight of being displaced and displacing colonial subjects. The work we have produced together methodologically uncovers and critiques the opaque confrontations of institutional power, racism, and colonial violence in the everyday. As a family, we continue to make uncomfortable pronunciations like chó bò, producing the epistemic trouble necessary to face the colonial realities of our resettlement.

Source: Cho Bo Trouble

I went to the opening of James Nguyen's exhibition Open Glossary at ACCA which also included the launch of his dissertation-turned-book Lám Chó Bò Making Trouble. Dubbed as the "most readable PhD dissertation," Nguyen exquisitely details his art practice that is inextricable from his family, and the dilemma they face when making art as refugee immigrants and settler-colonisers in Australia. In the book launch, Nguyen reads a poem by his mother, translated from Vietnamese to English. Settling in Australia in the 70s, Nguyen's mother never properly learned English as she spent most of her time on the sewing machine to make ends meet. In the wee hours of the morning, when she had a bit of time to herself, she wrote poems. Nguyen only found out later as an adult and discovered a new side to his "uneducated" mother. In the poem he shared, she acknowledges First Nations people and thanks them for giving her and her family a safe place to live in.

Coming here as an international student, I have been grappling with a similarly tinted problem, and it does feed into my artworks, one way or another. I'm constantly asking myself, why am I seeking opportunities in a settler colonial state? Am I complicit? But then I am also experiencing institutionalised racism and exploitation as a Southeast Asian woman. Should I even be making art here to cater to a Western gaze?

Nguyen has a diasporic background, so he is in a different ballpark... but these convolutions and entanglements are quite common, including, to students who are soon to be migrants. Because let's face it, most of the foreign students who come here have the intention to stay. I'm not saying I have that, but the way it was marketed to me when I was in the process of applying made it seem like there are generous, easy pathways to remain here. That's not really true. People move heaven and earth to be able to stay and fully enjoy the privileges of being an Australian national. The Australian government has built a multi-billion dollar industry to profit off international education and off the labor of working students. This is why COVID-19 hurt this industry so much, and this is why they made so many incentives to recover their lost workforce. This is an exploitation machine! And I'm a cog.

Again, not saying my experience matches up with Nguyen's, but he's in academia, where racism is entrenched. This now makes me ponder if I can enter academia down the line.

0 notes

Text

Snare for Birds

Snare for Birds: Rereading the Colonial Archive is a collaborative research art project of Kiri Dalena, Lizza May David, and Jaclyn Reyes that inquire into the tangents of the country’s colonial past, archiving, and its impacts on being Filipina. Distinct in their own practice, each artist negotiates their own and the current generation’s positions against an imperial past and present as women residing in the Philippines, Germany, and the United States.

The project builds upon the deeply embedded imagery and knowledge of Dean Worcester; whose photos were eventually bought by German merchant Georg Küppers-Loosen and is part of the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum’s archive in Cologne, Germany. Worcester, an ornithologist and Secretary of Interior of the Philippine Islands during the American colonial period, was known for his book The Philippine Islands and their People. Worcester’s views shaped US public opinion, foreign policy, and inevitably what we know to be Filipino history and identity.

Snare for Birds: Rereading the Colonial Archive challenges these deeply embedded imagery by reciprocating Worcester’s endeavor: to engage with archival images like specimens and to claim truths a camera was “made to tell.” It encourages viewers to question the colonial gaze, the accessibility of these historical records, and the ways in which our responses to these images shape how we engage with our predecessors. Finally, it asks what these images imply and reveal about Filipinos today considering that these have historically been used as evidence of Filipinos’ incapability of self-governance.

Since the collaboration began in 2020, Dalena, David, and Reyes have paved their own paths of inquiries while converging through thought partnership as seen on their website (https://www.snareforbirds.com). This act of working together in itself has become its own decolonizing ritual, as they intentionally interrupt the disembodiment of the global Filipino diaspora through piecing together parts of fragmented histories and solidarities.

The final iteration of the project to be mounted at the Ateneo Art Gallery is seen neither as a conclusion nor culmination of the research; rather, it is perceived to be a preamble for more avenues of conversations to ensue. Snare for Birds: Rereading the Colonial Archive is a look at our collective history in order to deal with the present with hopes of forging a just and equitable future. The colonial past, though riddled with pain and adversity, requires persistent disruptions not only to dislocate power structures but to also re-define what is known to be truths.

Source: Ateneo Art Gallery

An excerpt from Kiri Dalena

I did not duplicate the photographs for this entry in respect to the work of the artists. Please enter the website if you would like to see them.

Each artist has a section with trigger warnings before you can proceed to the artworks. Dalena features several photographs of indigenous Filipinos during the early years of the American colonial period. The people are depicted as specimen to be studied; their way of dress is shown, their flesh, various ailments, and infections. Dalena points out that while the photographs are not of the usual carnage from the Philippine-American war, they still contain implicit violence, as is eerily characteristic of colonisation. Colonisation armed with the sophistication of science and academia seems to be more sinister. In Edward Said's Orientalism, Napoleon's conquest of Egypt is cited as the start of such form of violence, with scientific and academic structures leading the way. This is how the Americans came to us.

Annotation 1

This reminded me of a friend's research essay where she describes how the lexicon of photography is quite violent. Capture. Shoot. Exposure. Aberration.

Annotation 2

Archival work as a form decolonisation and reclamation is valuable in the Philippines as having access to archives in the first place is already quite difficult to do. It is often painful to see that a lot of collections that tell our history are not even our own. We are not the custodians, and that seems to say that we do not have the authority to tell our own stories. Snare for Birds share some of the artist's difficulties in piecing together the fragments.

Annotation 3

Museums and archives are based off colonial models. To engage with them in the present context is a form of resistance and even healing. I feel that as Filipinos, we are born with open wounds through the transgenerational traumas we have after three centuries of oppression and denigration. Decolonisation through art and inquiry may help us close these wounds.

0 notes

Text

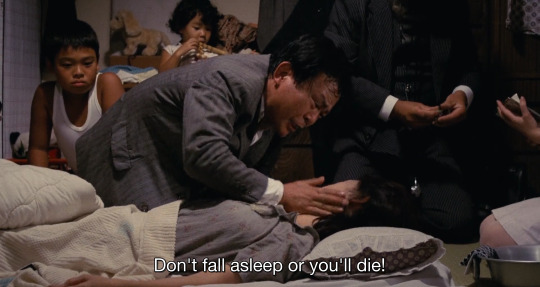

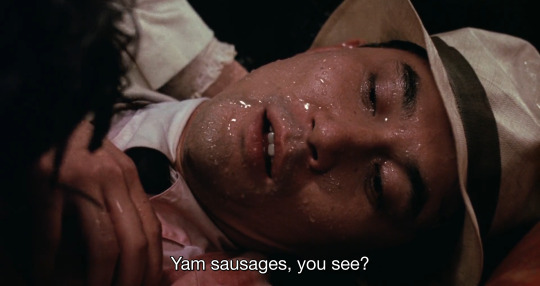

Tampopo (1985)

Comedy. Ramen Western. Dir. Juzo Itami

This film feels like a break from all the other entries.

Tampopo dubs itself as a "Ramen Western," a play on the subgenre Spaghetti Western. What I got from Itami's comedy is joy, the pleasures of food, and the overall ridiculousness of life. The titular character is a widow working to reconstruct and save her late husband's ramen shop. With the help of truck drivers and ramen connoisseurs Goro and Gun, she goes on (mis)adventures to improve her cooking skills and perfect her ramen recipe.

Ramen, a quick and cheap Japanese dish, is treated as a delicacy here. From the broth, the noodles, and the protein, everything must be in harmony. Even the eating process seems to be an art, as demonstrated by Goro's sensei. Alongside Tanpopo's quest for ramen greatness are humorous subplots. An old lady likes to squish soft foodstuff in a grocery, much to the chagrin of the shopkeeper. A con man gets so caught up in a lavish meal that he forgets to escape. A gangster and his lover engage in erotic food play.

A favourite of mine is of the dying housewife who uses the last ounces of her strength to rise from her deathbed and make her family one last meal.

Her family then keeps eating to memorialize her. It's so stupid, and that's what makes it beautiful. I couldn't stop laughing at this scene. I know, it's morbid.

It was through this reaction that made me realise I had been missing this type of rapture when it came to my own practice. My focus this semester had taken a deep dive into the eerie, psychological legacies of colonialism, so I had put aside my spaces for joy in order to focus on the research. I've found myself in a rut, so maybe a way out can be by not taking it too seriously.

Maybe I can take cues from Itami's film, which takes not taking things seriously at a sophisticated level. He highlights the everyday; finding magic and humor even though we're all really just doomed to die. To counter this pessimism, I do have to note that this film was released during the 80s, when Japan was economically prospering, before the bubble burst.

Back to dying, Itami touches on death several times in the film. Besides Tampopo's late husband and the housewife, one of the side characters is a wealthy old man with a fattened heart who almost chokes to death after enjoying his soba, tempura, and mochi too much. Another is the gangster, who gets shot in the end by an unknown assailant. Dying in his lover's arms, he talks about food, of sweet yams and wild boar meat.

Maybe the point is to enjoy things while we're here. Slurp that bowl of ramen as loudly and as rudely as you can. Have all the soft serve and sticky mochi you want. Enjoy meals with your loved ones. Be stupid. Live.

0 notes

Text

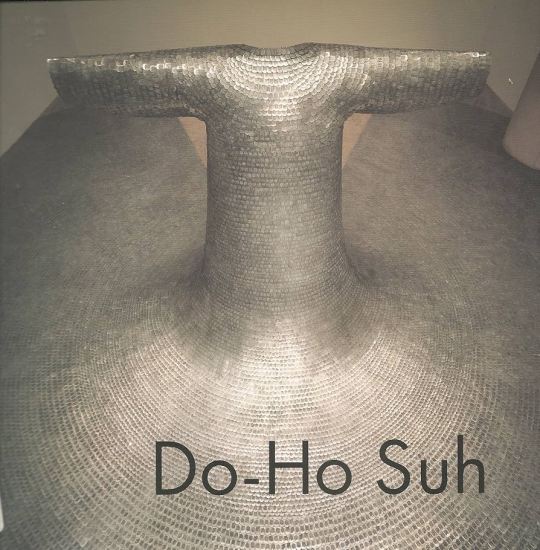

Miwon Kown on Do-Ho Suh

The ascendance of an artist like Do-Ho Suh in the international art scene is not only predicated on the high quality of workmanship, cleverness of ideas, strength and clarity of formal decision, and sophistication of talent. It is also linked to the fact that in the contemporary art world today, a culturally displaced person of adequate means who can navigate a bigger map of the world than those bound to one location, culture, or identity is treated as a representative if not privileged person, able to speak to, speak of, and speak as a retooled nomadic subject of globalization. Suh's recurring trips to Korea, motivated in large measure by the necessities of his production (labour is cheaper there), also mirrors the ongoing uneven distribution of labour, resources, and power in late capitalism. Thus, the attraction that Suh's work draws from a globalized art network of curators, dealers, collectors, and critics lies in the symbiotic fashioning of both the work and the artist within the logic of a new order of mobilized identities. Do-Ho Suh's art eulogizes the older paradigms of subjectivity, identity and space while announcing new versions of them as unlocated conditions of transience.

Selected excerpt from The Other Otherness: The Art of Do Ho Suh by Miwon Kwon (2002)

As I continue to pour over writings on Do-Ho Suh, I have found that no one articulates him better than Miwon Kwon, whose 2002 essay for Suh's show at the Serpentine Gallery, still holds today, over two decades later.

Kwon links Suh's contemporary practice to Minimalism and installation art, primarily in a Western context***. The artist did shift into a sculptural and installation practice after receiving further education in the US. This is always mentioned whenever Suh needs an introduction, because it immediately frames him as a transnational artist, and points to the cultural displacement he experienced, which largely motivates his thematic interests on memory and transience.

Kwon has written extensively about site-specific art and has identified the problematic nomadism artists have adapted, which the art scene greatly rewards. Everyone needs to be jet-setting anywhere and everywhere in order to become a high profile artist. This hurts site specificity, because you can't just parachute onto a site and create watered down artworks in such brief periods. Kwon points out that the peripatetic Suh benefits from this system, but not without merit. She praises Suh's ability to create installations that don't have to be bound to their sites, rather, they are meant to leave.

This made me cuss a lot... when will I find my own succinct intersection

She furthers that Suh's otherness as a Korean implant in the West has (quite ironically) managed to transcend in that it has somehow become universal. She cites his work Seoul Home, which is so specifically Korean but manages to tug at the heartstrings of so many. Displacement, transience, and longing for home (whatever the hell that is) are universal experiences. This is why his installations can occupy various spaces and still be powerful and resonant. While he states that he is selfish in that he primarily makes his works to satisfy himself, he still manages to transform the personal into public. This is what I am trying to resolve in my own practice. How do I go beyond my lived experience? It takes so much sensitivity, skill and nuance to properly contextualise and effectively communicate. I am waiting for my abilities to catch up.

Seoul Home/LA Home installed at the Korean Cultural Center in Los Angeles. 1999. This is one of Suh's earliest fabric architecture works, which catapulted him into the international art scene.

***I am wondering if there are better references to link to Suh, something closer to an East Asian context.

0 notes

Text

Stephanie Misa: An altar for the fleshy tongue

Stephanie Misa (Philippines/Austria) is a visiting Krems Residency artist and researcher whose work centres around decolonising methodologies. Her artistic practice connects multicultural collaboration, curating and feminist criticism to examine the phenomena of language in its oral form and the richness of multilingualism.

In her new installation An altar for the fleshy tongue, Stephanie Misa examines the relationship between language and colonisation. Can language be inscribed bodily, handed down through generations so one comes to know language as a sensory encounter, existing in an alternative, intuitive and non-indexed paradigm?

Source: RMIT Gallery

I was fortunate enough to attend the opening of this exhibition where one of my lecturers introduced me to Misa, who hails from Cebu, Philippines. She conducted a performance lecture soon after which was forewarned to involve some "cannibalism." Haha. She introduced a small Spanish donut-shaped biscuit called "Filipinos," passing them around for the guests to eat. "This is a Filipino," she said. "It is white on the inside and brown on the outside. It has a hole in the middle." People laughed nervously but took the cookies and ate them. I became uneasy as I heard the oohs and ahs--it was a tasty biscuit. I also took a bite, and then frowned. "But I'm a Filipino," I told my friend, who was sitting next to me. Misa then went on to explain the importance of language, the hierarchies imposed, and how she had never been so insulted by a name of a biscuit. She detailed how in the late 90s, the Philippine government under President Estrada tried in vain to get the Spanish manufacturer to change the name or discontinue the product. Keep in mind, Spain colonised the Philippines for over 300 years before selling us to the United States.

Source: Coconuts Manila

As Misa continued her performance, I started to cry profusely. I couldn't get the audience's laughter out of my mind. It felt so degrading and isolating; that a room full of mostly Westerners will never fully understand—and have full privileges to never have to understand—the trauma and afflictions we have as people from postcolonial nations. But art facilitates spaces where understanding might be achieved, and Misa cleverly and affectively creates such a space. I am however weary of the burden of having to constantly identify oneself as a transnational artist and a Filipino. Why can't I just deal with my own shit?

This constant identification has led my art practice to slowly evolve into a form of decolonisation. I've been questioning a lot of values I was raised on, and most of them were rooted in colonial mentality. It feels like a form of deprograming, wrenching out the internalised. Whether this process will liberate me, or at the bare minimum, teach me acceptance, will most likely remain unanswered as I near the end of my MFA. But then this is what a practice can be furthered upon!

0 notes

Text

The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness (2013)

Documentary. Directed by Mami Sumada.

Sumada follows the founders of the renowned Japanese animation company Studio Ghibli: Hayao Miyazaki, Toshio Suzuki, and Isao Takahata as they complete their films The Wind Rises and The Tale of Princess Kaguya. The film focuses more on eccentric curmudgeon Miyazaki and media savvy Suzuki, with the elusive Takahata working in a separate studio. The film dives into the production of Miyazaki's "final" film while also exploring how his professional and personal relationships laid the foundations for Studio Ghibli.

There is already much scholarship on Miyazaki's films and his antiwar stance, so I'm not here to comment on that...

Rewatching this after almost eight years, I found myself more interested in the relationships between Miyazaki, Suzuki, and Takahata. Miyazaki seems to get along better with Suzuki than Takahata. Perhaps because he isn't a director. Of the three founders, he is the producer, and this has made him an intermediary between the two directors. Suzuki describes Miyazaki and Takahata's relationship as a rivalry, evolving from mentor-mentee, as Takahata had taken Miyazaki under his wing during their early years in Toei Animation. Miyazaki (aka Miya-san) cites his relationship with Takahata (aka Paku-san) as "finished," having collaborated with him for over 15 years before deciding to direct himself.

Sumada's documentary leans into the glimpses of the complicated relationship between the two, and builds tension through Miyazaki's comments for his senior (a back and forth slew of praises and insults) and Takahata's frequent avoidance.

Suzuki markets this to their advantage. In a press conference announcing the double bill of The Wind Rises and The Tale of Princess Kaguya, he remarks that the two directors' rivalry drives them both to push their craft. At least to the press, it is framed as a healthy competition.

A scene that I have been playing on loop in my head is one with Suzuki...

I've decided that Suzuki takes the cake on this rewatch. Miyazaki and Takahata may have been the genius animators, but it's Suzuki that kept them running and at least on speaking terms.

Now, why is this of interest to me?

My understanding of my artworks this semester has shifted into taking into account my embodied viewers (as one does with installation art). As I shifted from sculptures to installation, the object no longer becomes the focus but also accounts for the space and the viewers that will enter this. I'm inviting people in, and this has in turn pushed me to consider other ways where people can be involved not just through interacting with my installations, but well into the creative process as well. This entails collaboration, and that means knowing how to develop and maintain relationships. I'm dying to learn how to do that. What was Suzuki's secret?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

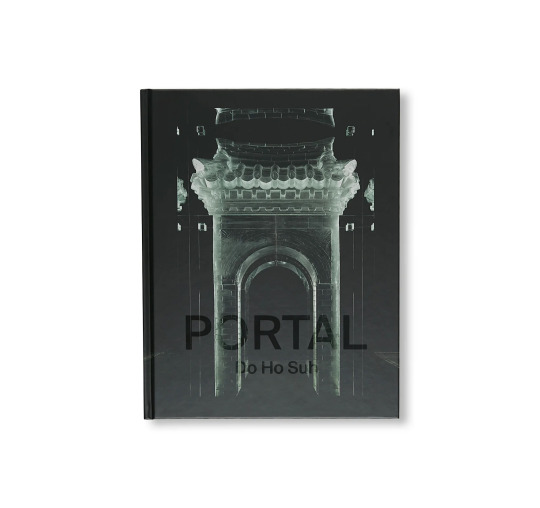

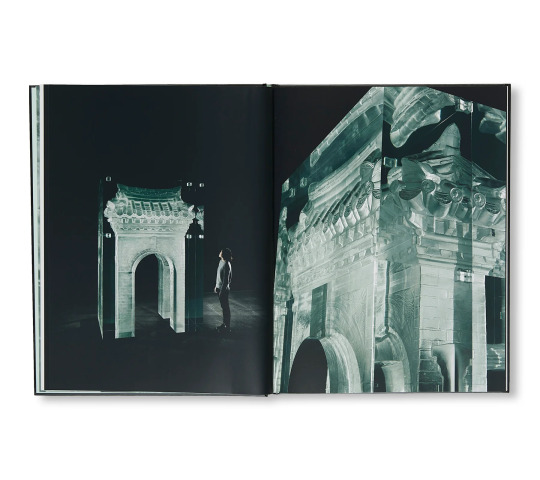

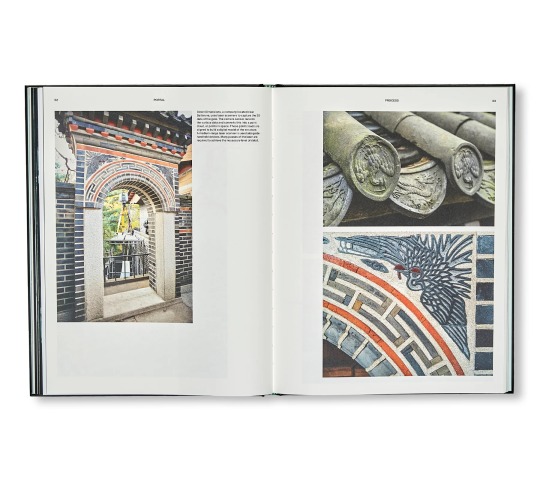

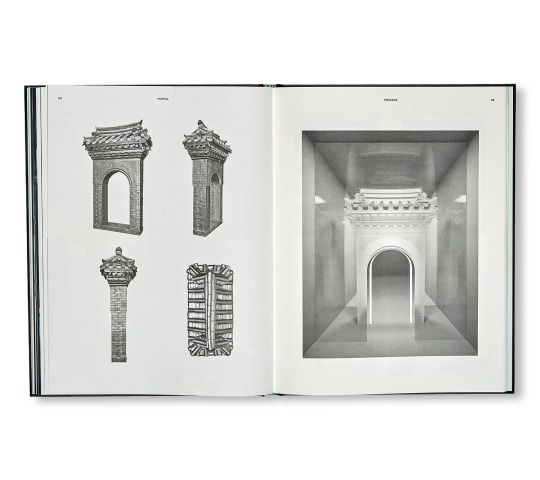

PORTAL by Do Ho Suh

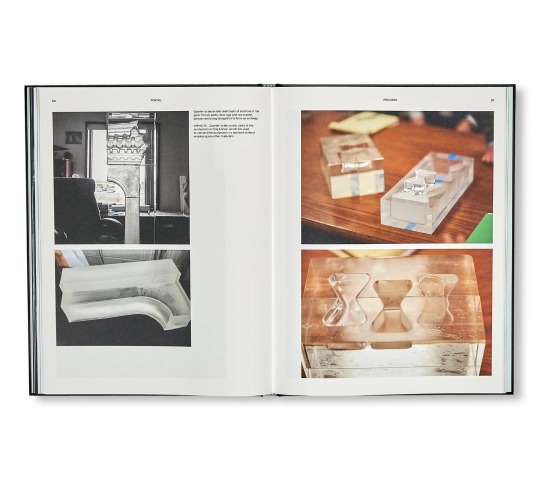

In 2006, London-based Korean artist Do Ho Suh (born 1962) began work on a seemingly impossible project—to “make something out of nothing,” casting the negative form of a traditional Korean gate in solid acrylic resin. Portal would take nearly a decade to complete, and would provide the site for fundamental developments in Suh’s thinking on the role of both artist and museum in the 21st century, as well as the relationship between East and West.

This volume tells the epic story of that process through those who made it possible. Through color illustrations and texts, it provides unique access to the typically veiled fabrication process: the process of scanning, modelling, and constructing a nine-ton sculpture that would appear as if it was not there, a “living ghost image” cast from negative space.

Source: Twelve Books

Suh hangs up his signature transparent fabric for some resin and "nothing" to make his impossible sculpture. Commissioned by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH) with curator Peter C. Marzio in 2006, it took nine years to complete, with Marzio tragically passing away five years before its completion.

I found it particularly astounding that a concept and vision could weather time and burueacracy triumphantly, albeit bittersweetly. Besides the technical feat, Portal's epicness rested on the persistence and support of Suh's collaborators. No artist is an island.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cornelia Parker's Transitional Object (PsychoBarn)

Exhibition Overview

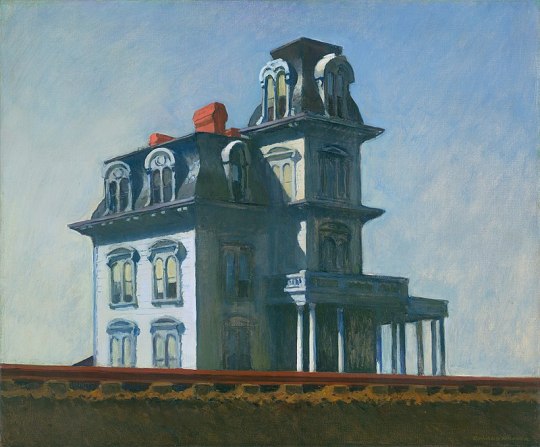

A large-scale sculpture by acclaimed British artist Cornelia Parker, inspired by the paintings of Edward Hopper and by two emblems of American architecture—the classic red barn and the Bates family's sinister mansion from Alfred Hitchcock's 1960 film Psycho—comprises the fourth annual installation of site-specific works commissioned for The Met's Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Roof Garden.

Nearly 30 feet high, the sculpture is fabricated from a deconstructed red barn and seems at first to be a genuine house, but is in fact a scaled-down structure consisting of two facades propped up from behind with scaffolding. Simultaneously authentic and illusory, Transitional Object (PsychoBarn) evokes the psychological associations embedded in architectural spaces. It is set atop The Met, high above Central Park—providing an unusual contrast to the Manhattan skyline.

Source: The Met

As a site-specific installation at the Met, one of the most visited museums in the world, it's easy to lean into pure spectacle. Parker does this without being vapid, using it precisely to poke at America's obsession with spectacle, especially in politics. Weaving together American references (Hopper, the classic horror Psycho, and the red barn) she does so seamlessly with this comically horrific amalgamation while also acknowledging her position as a Briton connected to the US by mirroring Hitchcock's assimilation into Hollywood.

It's all a facade...

Parker's house is red from appropriating the materials of a dismantled barn. The structure disrupts the New York skyline but also screams (psychological) Americana.

The creative process behind the sculpture revels in research; from Dutch barns to the artist's affinity for pop culture. Parker translates her unease stemmed from an unstable political climate (this was in 2016, right before Trump was elected) through humour. I am trying to find this magic (for lack of a better term), this intersection of intention and everything else falling into pieces as if by fate.

Edward Hopper. House by the Railroad. 1925.

Source: The Met

The Bates house from the film Psycho. 1960. Dir. Alfred Hitchcock.

Source: Universal City

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kengo Kuma: My Life as an Architect in Tokyo

by Kengo Kuma

On the book overall: Architecture feels like the pinnacle; form and function are seamlessly woven together. Kuma the Tokyoite achieves this. He solves problems through architecture but also purveys Japanese culture.

My works will never be as monumental, nor will they design their way out of problems. I've left the realm of design, but it will always inspire me.

Selected excerpt

Suntory Museum of Art

For the interior, I used paulownia wood, a wonderful soft material that absorbs moisture, which is why it was used for storing kimonos. Paulownia wardrobes were commonly taken by a bride to her new husband's family home when she got married. Another important choice of material was the oak used for the floor. The Suntory distillery is known around the world for its superior whisky, so I decided to make use of the oak planks from their old barrels, applying heat to flatten them, before laying them as floorboards. Some visitors say they can still smell the whisky as they tread on them.

p. 49

In design, material selection is geared towards minimising cost while still attaining performance goals. Kuma's choice of material are functional and genuinely responsive to the sites while also managing to be poetic. He digs into the material's history, context, and cultural significance, resulting in powerful, evocative structures.

Being poetic is quite central in my sculptural installations, which I enforce with a very structured creative process. It feels almost calculative, where every single decision must have a purpose—nothing accidental. Otherwise, why should it even be there? This most likely owes to my training in information design, but I am also quite the perfectionist... I apply this approach to my choice of materials. Materiality is key, and this directly impacts the evocative quality I always strive for in my artworks. Kuma made his visitors nostalgic for whisky; I want my own version of that.

0 notes