Text

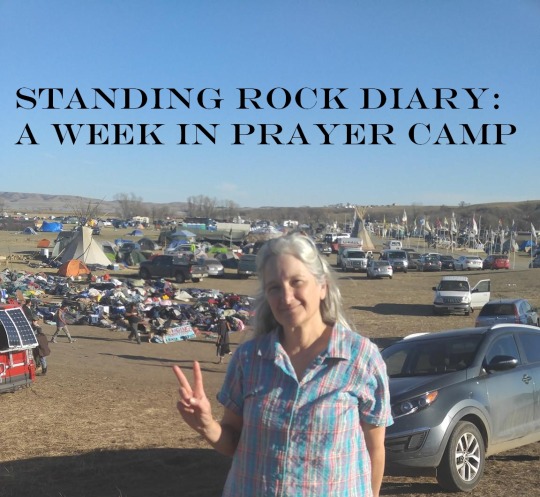

Standing Rock Diary--Memoir of the Protest Prayer Camp

Preface

I went to Standing Rock because it was finally time for me to do something that I really believed in. Although I had many opportunities in the past to become active in environmental issues, this time there was an additional subject I felt very strongly about: the rights of American Indians. The Standing Rock Sioux people were asking us all to come and be part of their protest against the Dakota Access Pipeline. I took the invitation almost personally.

I intended to write this as a diary of my week-long visit that would amount to about seven pages. It is not a work of art. After my return home, I woke up each morning with the same compelling thought that I had to write down everything that I remembered. Even after I had this book professionally edited, I added many more events, stories, and details. Therefore, any errors in punctuation, syntax, or grammar are purely my own.

Initially, when I wrote, I did not have an intended audience or purpose. At times I censored myself. I don't want my participation in ceremonies to be mistaken for belief. I value my personal rituals, equating spirituality with psychological strength, but action is usually required to manifest my intentions. This became clearer to me by being at Standing Rock: I believe the pipeline must be stopped. I joined in the ceremonies and prayed with the people, listening to their stories of oppression, gaining compassion, knowing that the color of my skin has its own privileges. I went home and wrote a letter to President Obama; the next day the Army Corps of Engineers halted the construction of the pipeline.

Since I asked very few questions while I was there, I found myself researching sources on the internet during the process of this remembering. I did not document these with footnotes or bibliography. This wasn't intended to be an essay, a research paper, a manifesto, or a propaganda piece. Every piece of new information led to a search for more information. My interest in the history, geography, geology, news, legal issues, personal stories, and tribal stories is almost without bounds. If I were to keep up with my research, this short diary might turn into an encyclopedia. I have to stop somewhere. Trust that my sources were reliable ones: mainstream press, official websites, scientific journals, blogs, and a few books.

There are probably dozens of people documenting their unique experiences and thoughts about living at the Standing Rock camps. Many are doing this with their cellular phones, filming, photographing, and taping. I imagine that at this writing, it's just too cold there for ink to flow out of a pen, and that no one is plugged in to their personal computer long enough to write at length. They are more likely to be documenting in the form of direct messages: short emails and text messages, photos and videos, and posts on social media.

This diary does not flow like a story I would tell over beers to a friend, or as private notes to myself. At times my words give voice to some internal struggles of my own. But now it is time for me to finish the writing as I believe that it is timely. Finally, it does have a purpose: it is a call for Unity and for Action.

Monica Lee Shimkus

January 2017

introduction

Bakken oil fields

The Bakken Formation is the name of a rock unit underlying parts of Montana, North Dakota, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba that is a natural source of crude oil. The oil is extracted by horizontal drilling technologies and by hydraulic fracturing or "fracking" during which water, sand and chemicals are shot underground to break apart rock and free the fuel. The result has been a boom in Bakken oil production since 2000. Production is near a million barrels a day and is conducted by over 35 different active companies and lease operators, including the Halliburton Company. The light "sweet" crude oil in the Bakken Formation is found “trapped” between layers of shale rock about 2 miles below ground with no surface outcropping that might allow volatile or gaseous compounds to escape. As a consequence, when the oil is extracted it often contains high levels of these compounds and is more prone to explosion than other types of crude oil. There have been many accidents in the field and in transport of Bakken oil resulting in explosions and fires. It is hazardous to extract and to transport by rail or by any other means.

Energy transfer partners

Energy Transfer Partners began in 1995 as a small intrastate natural gas pipeline operator and now owns and operates approximately 71,000 miles of natural gas, natural gas liquids, refined products, and crude oil pipelines within the United States. ETP is building the Dakota Access Pipeline, a 3.8 billion-dollar, 30-inch diameter underground pipeline intended to carry oil 1,172 miles from the Bakken oil fields across North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa and Illinois to an oil tank farm near Patoka, Illinois, a hub that connects many oil pipelines. This pipeline will transport 470,000 barrels of oil per day. An early proposal for the Dakota Access Pipeline called for the project to cross the Missouri River north of Bismarck, but one reason that route was rejected by the Army Corps of Engineers was its potential threat to Bismarck’s water supply. The population of the Bismarck metropolitan area is 130,000 people, of whom more than 90% are White. The new proposed route runs about 30 miles to the south, less than a mile from the Standing Rock Indian Reservation boundary (of which the population is 78% American Indian) at Lake Oahe, a 231-mile long reservoir on the Missouri River.

In an audio recording from a September 30, 2014 meeting with Energy Transfer Partners, while the pipeline was still in its planning stage, Standing Rock tribal officials expressed their opposition to the pipeline and raised concerns about its potential impact upon sacred sites and their water supply. On December 18, 2015, the United States Congress voted to put an end to its 40-year-old ban on oil export. Not all the oil from the Bakken fields is intended for U.S. consumption: in April of 2016, Hess Corporation sent 175,000 barrels of Bakken crude oil to Rotterdam, in the Netherlands. By May 23, 2016 construction of the pipeline was reported as underway in 3 states. Many of the construction permits were acquired through eminent domain. In a Wall Street Journal interview published on November 16, 2016, Energy Transfer Partner's CEO Kelcy Warren said that he wished that the Standing Rock Sioux “had engaged in discussions way before they did” about the new pipeline. He also said that obstacles will disappear under President-elect Donald Trump, who was at that time invested in ETP. In a Reuters article dated October 16, 2016, Kelcy Warren had donated more than $100,000 to Donald Trump since June, according to campaign finance disclosure records.

#nodapl

The Dakota Access Pipeline protests, also referred to as #NoDAPL, began in April 2016 and are, at this writing, ongoing. At the heart of the protest are the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation and Tribe. There are three reasons for Indian opposition to the pipeline. First, they want to protect their water supply from oil spills. Second, there are sacred sites in the path of the proposed pipeline: graves, stone prayer circles, stone cairns, some of which have already been destroyed by construction workers. Third, the pipeline is being built on some nearby land that Dakota Access bought but Standing Rock Sioux claims as their own. The land was granted to the Sioux in the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty which was signed by eight tribes and the United States government. The Sioux say that they never ceded this land in any subsequent treaty.

The Sacred Stone Camp was formed on private land on Standing Rock Reservation. Situated on the south side of the Cannonball River, it was created to provide shelter to people who were coming in to pray and peacefully protest the pipeline at the construction site. In July 2016, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe filed suit against the Army Corps of Engineers to halt the pipeline's progression. The suit alleges that the “Corps” violated multiple federal statutes, including the Clean Water Act, National Historic Protection Act, and National Environmental Policy Act, when it issued the permits to Energy Transfer Partners. In a few months, the Sacred Stone Camp population grew and overflowed to the other side of the Cannonball River and the protests began to draw international attention.

The world is watching

On September 20, 2016, David Archambault II, Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Chairman, addressed the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva, Switzerland to garner international opposition to the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline near the reservation. By late September, NBC News reported that members of more than 300 federally recognized Native American tribes were residing in the three main camps, a historic gathering, alongside an estimated 3,000 to 4,000 pipeline resistance supporters. In spite of the protesters' non-violent, prayerful stance at the construction site, police had responded with pepper spray, attack dogs, mace, tear gas, water cannons and rubber bullets. At this writing there have been hundreds of arrests during protests at the site of the construction and at other locations, such as banks that are funding the pipeline and Army Corps of Engineers offices nationwide. Reporters, journalists and officials have also been arrested, including Amy Goodman of Democracy Now and Tribal Chairman David Archambault. Mainstream news reporting was sparse, but stories, photos and film footage were available to the public on social media. On October 31, 2016, a United Nations group was sent to investigate human rights abuses by law enforcement at the protests. Much of the pipeline has been completed as of late 2016, so the Missouri crossing has been an increasingly contentious issue. On December 4, under President Obama's administration, the Army Corps of Engineers announced that it would not grant an easement for the pipeline to be drilled under Lake Oahe. In the meantime, the “Corps” will prepare an Environmental Impact Statement for alternate routes. However, many protesters continue camping on the site, in spite of the harsh winter conditions, not considering the matter closed. On their website, Energy Transfer Partners vows that they "fully expect to complete construction of the pipeline without any additional rerouting."

pipelines leak

Throughout the United States, there are 1,079 different crude oil pipelines that cross inland bodies of water, including eight that cross the Missouri River, amounting to more than 38,410 existing river and waterbody crossings. In 2016 alone, there have been 30 reported major crude oil and natural gas pipeline breaches and accidents in the United States, causing property damage, fires, death, harming wildlife, and fouling water. On December 5, a leak was reported to regulators that an estimated 4,200 barrels of oil spilled from the Belle Fourche Pipeline with an estimated 3,100 barrels going into the waters of the Ash Coulee Creek about 150 miles from Standing Rock. On March 23 2017, an updated report in the Bismarck Tribune states that the leak was more than four times that amount, 529,830 gallons, and began on December 1 and was discovered by a landowner. Almost four months later, the cleanup is still underway.

A complicated way to prepare for a journey

It took a relatively long time for me to get there, from the time my friend in Arizona, Frank DePonte, sent me a message, “My wife, a journalist, is covering the Dakota Access Pipeline story for a Russian magazine. We will be at Sacred Stone Camp in ND for the holiday weekend. Will you be there?” That message came to me before Labor Day weekend when the action was beginning to get heavy and the press was beginning to take notice. I had not been following the story, and I was learning that a pipeline was being built that the local Indians did not want. That was the short version of the issue as it was known to me then. Of course I should be there.

Autumn is my usual travel time. I have always been financially strapped, but I love to plan travels. In reality, I get out the door with some psychic difficulty. Indecision is a state of mind I have accepted but nevertheless struggle with. There are so many choices of where to go, how to get there, where to stay, people to visit, and what I might want to do along the way. Two months passed while I agonized over taking what was going be my “Summer Vacation.” When I travel, I am usually going to be working or studying. Sipping a cocktail on the beach is not my image of Somewhere Else. Occasionally it is quite clear to me what I want to do, and where I want to go, and then I just do it. When I make up my mind I can be on a bus out of town first thing tomorrow. I began to foresee that this year my destination was going to be Standing Rock. I wasn’t sure for how long, or what I would be doing, or if I would enjoy being there. The way I see it, American Indians have every right to hate me and the entire White race for the vast amount of irreversible damage we have inflicted on them. If I went, I would be camping out in cold weather, and there was plenty of reason for me to believe I would be in a situation where I could be arrested as there were reports of protesters and police colliding.

I learned that protesters were planning to camp out on the land over the harsh winter and I came to rationalize that I needed to assist with building housing for the people who would be staying. I have some knowledge of construction, architecture, native structures, and small experience with Habitat for Humanity, and I was growing excited with the idea of being busy using what I know. I spent my mornings researching the people who lived in North Dakota when the Europeans arrived, the Arikaras, the Mandans, the Hidatsas, before the Sioux came to live there. I studied quickly-built sustainable as well as temporary housing forms that could protect people from the cold: quonset huts, straw bale, earth lodges, yurts, and insulated teepees. I began reading Grandmothers Counsel The World: Women Elders Offer Their Vision For Our Planet by Carol Schaefer and Rolling Thunder by Doug Boyd. I was becoming conscious from the contents of both books that Spirituality and Environmental Stewardship are interconnected in the minds of many indigenous people. The current events coming to a head a Standing Rock were pointing my attention to the legal and diplomatic struggles for the Indigenous peoples of the whole earth. It was becoming more evident that I needed to go. Even if my presence was not going to effectively help the people who live there or the campers or the protest, then I simply I needed to go to fill an educational gap in my own life’s experience. I would go to learn.

**********************************

Late in September and still in an aggressive state of indecision about making the trip, I packed up my tent and went camping about 30 miles from my home, at the New Jersey shore. It took a few attempts to actually make it to the beach due to self-sabotage, including leaving my wallet at home, setting out too late in the day, and locking my keys in the car. Finally, the day I picked to go camping happened to be very windy with rain in the forecast. When I finally arrived, I found that I had the whole lonely campground to myself. I took a walk on the beach; there were a few brave or crazy surfers on the especially rough-breaking waves. Before I picked my campsite I found a dead sparrow. Should I be superstitious since “Sparrow” is my nickname? I picked a site and set up my tent. The wind was unrelenting and provoked a kind of misery; I slept badly and the weather prevented me from making my own coffee in the morning. At dawn I renounced sleeping out of doors. I left my tent and stood in the wind and prayed out loud. I never know what good praying does but I asked to be decisive, to know my purpose, and to use my gifts to make a difference in the world.

But the wind was preparing me for the conditions at Standing Rock.

***************************

In October I wrote a letter to my friends in a few places who had been expecting that I might visit them, explaining that I was considering going to North Dakota instead. I had credit card points that would convert into free or cheap flights, but would limit my airline choice. Inexpensive voyages often happen during the off-season, away from holidays, midweek, and during off-peak hours. Bismarck Airport did not appear to be conveniently situated. I would have to arrive by airplane sometime late at night and leave very early in the morning. I was having a hard time visualizing a pleasant or easy passage. The autumn days were growing shorter and I was running out of time for the advance planning required to ensure the best bargains. At the same time, tensions were escalating at the site; the pipeline construction was growing nearer to the Missouri River as I kept watching the weather report. The summer season was apparently having an extended stay in North Dakota, just as in New Jersey. It would be a good time to go; if I waited too long I would miss the best building weather.

I had read that there were two camps at the site and the one called Sacred Stone was on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation on private land owned by LaDonna Brave Bull Allard. They were calling themselves a “Prayer Camp” and were accepting money and material donations over the internet. From the pictures I was seeing on social media, I imagined that in the future this place could one day become a permanent educational facility. There was also a public fund for legal aid which was growing steadily and had already far exceeded its fundraising objective. There was another camp, as I understood it at the time, that was called Red Warrior, and my impression was that it was for activists who were planning to participate in civil disobedience actions. I had decided that if I went, I would be staying at Sacred Stone Camp, although I kept picturing myself at the "front line" carrying a sign that read, "This is your water, too. Join us." But I still had not made up my mind to go.

I had a few remaining things to do around my home to get ready for winter. I had to repair my garage door that had been damaged by snow plows last winter. I sold off a few things on eBay to raise money. And then an opportunity came to buy a good used car for very cheap. The actual purchase was quite a hassle, full of anxious days, as the car had been sitting in a driveway and not driven for five years, the original title was missing, and the owner being disabled, could not assist me. It was a lot of footwork, money I didn’t have, insurance, towing, mechanical repairs. But, if I wanted, here was an alternative way to get to Standing Rock, that is if I didn’t mind adding six days of driving to and from North Dakota to my travel plans.

*****************************

Then, I had a sudden flash of a long-ago memory of my seeing the Missouri River for the first time. It was around the 24th of June, 1981. I had just spent a month in St. Paul, Minnesota working to pay my way during my first cross-country road trip. While I was at work one day listening to the radio, I heard that the Sioux Indians were planning to occupy the Black Hills in an ownership dispute and I wanted to be part of the experience, somehow. It was time to pack up my car and head toward Wounded Knee, South Dakota. I was driving with very little money and some camping gear. I picked up a hitchhiker earlier in the day and we stopped in to check out the Corn Palace in Mitchell, South Dakota. We continued driving on I-90; night fell, and I was getting tired from driving. My hitchhiker suggested that we pull over at the nearest rest stop and just roll out our sleeping bags, and so we did. I remember the night being comfortably warm and lightly breezy. I looked up to see a sky filled with thousands of bright stars. It was my first time sleeping under an open sky at night. In the morning I woke to the strange and beautiful song of a meadowlark. I also saw that I had been sleeping on a hillside, and down below, way down at the foot of the hill, was a river that I found on my map to be the great Missouri. It was impressive, about half a mile wide, surrounded by green, grassy hills of early summer. In researching for this preamble to my Diary, I learned that the Missouri is the longest river in North America. There are many dams along the river that make it wider than it is by nature. They were built by the United States Army Corps of Engineers for the purposes of irrigation, flood control and the generation of hydroelectric power. The Pick-Sloan plan for the development of the Missouri River included the construction of four dams between 1946 and 1966. The Oahe Dam at Pierre, South Dakota, created the 231 mile-long Lake Oahe, where the Dakota Access Pipeline is designed to pass underneath. In addition to flooding forest and farmland, and reducing the size of Indian lands along the Missouri, the construction of the four dams forced the relocation of nearly 1,000 Native families. The damming of the river “caused more damage to Indian land than any other public works project in America.” I now know that the river at this point where I was seeing it was the Eastern border of the Great Sioux Indian Reservation that covered the western half of South Dakota according to the original Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851. The Sioux still claim that land as their own.

***********************

On November 1, I phoned Frank with my dilemma of being crippled by indecision. I needed to be talked into going to Standing Rock. First Frank offered to fly into Bismarck himself and rent a car to facilitate my journey. Then he said his wife would come with him and gather more research for her article. But the final tipping point came when he started singing the song “Chicago” by Graham Nash to me:

"...In a land that's known as freedom how can such a thing be fair?

Won't you please come to Chicago for the help that we can bring ..."

With this, my decision was made. I hung up the phone and immediately made my one-way airline reservation to North Dakota. I would meet Frank in Denver to get our connecting flight on the same plane to Bismarck. I had already been packing for this trip, and a large part of my anxiety had lain with my bringing the right versatile gear, yet not too much for me to carry without help. This was all going to be remedied by Frank’s renting a vehicle to transport us to Standing Rock, which was 50 miles south of Bismarck. I finished the repair of the garage door and in the process cut my hand, a short gash. I cleaned it and bandaged it so it was not going to be a problem but it was later to become an image that would represent my journey.

On November 2, I went out and voted in our upcoming national election. Later that day I was in a store that had a television on, and as I was shopping there was a news broadcast showing film footage of a violent clash between protesters and police that had taken place only a few hours earlier in North Dakota. In the scene people were wading in the Missouri River at the pipeline construction site. Police dressed in military riot gear were streaming mace at protesters and shooting them with rubber bullets. I wanted badly to see these police put down their weapons and join the people. My decision was still to go in support of the protest, and not with the intention of getting arrested. My hope, although unrealistic, was that the issues would all be resolved before I returned home and that no one would have to camp over the winter and no one would have to show up and protest anymore.

Thursday, November 3, 2016

Before I left home, I made a return flight reservation. I wasn't sure how I was going to manage to be on an airplane out of Bismarck at 6:20 in the morning, but I trusted that somehow it would happen. I was going to be gone eight days and nights. Packing is normally difficult business for me and I can alternate between being very fussy and very adaptable. The day was warm so I wore a long black skirt and sports sandals. It felt like I might be carrying too much, but I was greatly relieved to find that my bags were easy for me to handle. My life partner, Howie, said he wished that I was not going, but he said he respected me because I was going and this made me feel really good. He drove me and my bags to the train station. I didn't have to wait more than a few short minutes before the train to Newark airport arrived. I was early for a change and I had plenty of time before take-off. When I got to the gate there was a little bit of a hassle regarding the manner in which I had loosely packed my sleeping bag, but I got it onto the airplane just fine. I visited the United Airlines VIP lounge for some free soup and salad and a glass of wine. I had brought a book with me to read, Marquee Moon, by Bryan Waterman, the story of the making of the 1977 LP by the band Television. It was a conscious choice for me, a small portable book about the 1970s New York City art and punk music scene. I knew that where I was going was going to be far removed from the story contents of this book, but I felt I might need a reference, a touchstone, connecting where I was going with where I am from. Then I boarded the plane, flew into Denver and met up with Frank and his wife, Radjana, a Russian anthropologist who was working on the story of the pipeline and the resistance for the Russian press. After leaving Denver, I was not going to have any cell phone reception so I sent out a few final text messages. On the connecting flight from Denver to Bismarck I was seated next to a peace activist, Reverend Patrick McCollum, who told me he was in contact with the United Nations and President Barack Obama, and that on that day over 500 clergy had converged at Standing Rock. He told me that a Peace Pole was being shipped from Japan and that he was going to carry it to the site.

We arrived in Bismarck at around 8:30 p.m. Frank rented an SUV and got us a hotel room. The neighborhood was not far from the airport, full of chain hotels and restaurants presumably designed to serve business people and travelers. I was hungry and requested that we get something to eat so we picked out a restaurant very nearby. We walked in and were greeted by girls about 18 years old, wearing football jerseys as their work uniforms. We took our seats at the bar. There were at least 70 very large televisions on the walls, surrounding us on all sides, all tuned to broadcasts of different sporting events. When I travel I like to get a feel for the locals. I looked around to study the clientele, mostly white males, about early 20s in age, mostly wearing sports clothes, as if they had come in from a game themselves, and all very well-fed. If there were cowboys among them, they were out of uniform. It was after work hours. There was a feeling of familiarity among patrons and staff alike. I would take a wild guess that there was a university nearby and these were students, possibly of agriculture, mining, or business. For the next seven days this was going to be my last contact with mainstream white American culture. I ordered a hamburger because it seemed like the most local food choice, and a beer. By the time we finished eating it was about 10:00 p.m. We went back to the hotel and I took what I expected would be my last shower for the next week and I went to bed.

Friday, November 4, 2016

First thing in the morning, I turned on my laptop to look at a map, the weather report, and find out what news there might be from the front lines or the camps. Frank had heard rumors of roadblocks and communications jams. I already had no phone reception, and I knew I would not have internet connection for possibly the whole week. The mainstream press was not fully committed to reporting the story of the pipeline or about the conflicts that were regularly occurring between armed police and unarmed demonstrators. I sent a message to my family that I had arrived. I was following several Facebook pages that posted news from Standing Rock daily, often up to the minute, mostly in the form of videos, some of them posted live. There I found news and photos of the 524 interfaith clergy that had arrived the previous day, publicly demanding justice for indigenous peoples. As part of their demonstration, they renounced the Doctrine of Discovery, a concept that allowed European colonial powers to lay claims to lands inhabited by indigenous and non-Christian peoples, enslave or kill the natives, and take their resources under the guise of discovery and spreading Christianity. The idea of the Doctrine goes back as early as the Crusades in the 11th century and over time was written into official documents and laws. At their demonstration the clergy sang hymns and burned a copy of the Papal Bull “Inter Caetera,” that was issued by Pope Alexander VI in 1493, declaring Spain's rights to lands discovered by Columbus the previous year.

It was a beautifully sunny and cool morning. We got some breakfast and set out for the Reservation. The cities of Bismarck and Mandan, on either side of the Missouri River, were old prairie towns, and had been sites of settlement over thousands of years by different waves of people. There is archaeological evidence of 11,000 years of human occupation in North Dakota. The Mandan Indians were the inhabitants of the Bismarck area and totaled an estimated 15,000 in number when the Europeans arrived in the 16th century. Lewis and Clark passed through the area in 1804 on their Expedition. A series of smallpox epidemics reduced the number of Mandan to about 125 by 1845. Today, White northern European descendants, mostly Germans and Norwegians, make up the largest ethnic group in North Dakota.

The direct highway to the reservation, ND 1806, was indeed blocked, presumably by police, as Frank had anticipated and we had to take a detour. The landscape as we drove out of the city was grassland with very few trees. There was an occasional small farm with corn growing, and some small cattle ranches. But mostly the land appeared to be fallow, or grazing land for cattle and buffalo, or else the grass itself was harvested as hay which was rolled in large bales scattered around the countryside. I wondered what it might be like to live there.

When we arrived at the junction of roads near a place called Cannon Ball on the Standing Rock Reservation, there was a tribal police mobile command post. We could not guess what their presence signified, but we pulled our car over and checked our directions. When we had ourselves set on the correct trajectory, we found signs pointing to Sacred Stone Camp at a roadside convenience store. We followed the signs until we found a gate that had its own camp with a big army tent and many people roving around. A woman approached our car and we rolled down our windows to talk with her. She spoke with an Australian accent and questioned if we were agents of the FBI or other government agency or the press and what we were planning to do here. She told us that no drugs, alcohol or firearms were permitted, and photography was not allowed unless we asked for permission, and then she let us proceed on into the camp.

We parked the vehicle and walked through the camp which was a mix of tents and teepees, and tarp structures built into the shrubbery. I was interested in the primitive tarp shelters, but looking into the shrubs I saw that they had lots of big thorns, and I was glad that I had a free-standing tent with me. Being situated on a series of hills, it was not possible for me to see the extent of the camp or to guess how many people there were. Everyone was friendly and many were dressed colorfully. Although there was no running water, no one appeared as if in dire need of washing. I soon encountered that same Australian woman who had greeted us at the entry gate while walking on a path. I asked her to give me a quick tour and she showed me the kitchen. In the midst of the kitchen was a Sacred Fire with seats around it. She explained the rules to be observed: no cursing, no gossip, and no political talk. Praying was welcome. There was a dishwashing station. Although I saw no open food about--except for whole fruits--I noticed quite a number of common houseflies landing on the tables. I asked about winter housing structures and she brought me to a spot where people were constructing what they called “Waginogans”--Quonset-style longhouses made of bent saplings that were going to be covered with blankets and tarps. I was looking forward to helping out.

However, the Sacred Stone Camp was not the same center of activity that Frank and Radjana had visited the last time they were here. It was a completely different camp. We walked on and came to another gate that closed the road to vehicular traffic. It was another formal checkpoint with a large canvas tent, a few chairs around a small fire, a young man who had been awake too long with a walkie-talkie, and his dog. We talked with him about the logistics of this gate, and I got the vague sense that it could be locked at any time, as a defense in the case of a raid. I did not understand much of what he was trying to tell us because he spoke in “warfare” terms that were unfamiliar to me. We continued to walk along past the gate and there in front of us was the Cannonball River. The river gets its name from the spherical sandstone concretions, rocks resembling cannonballs that were formed over time in a whirlpool that was at the junction of the Missouri River. The Lakota name for the Missouri is Mnisose, "swirling waters" which refers to the eddies that occur at the confluences of its many tributaries. According to LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, since the damming of the Missouri, and the Army Corps of Engineers' dredging the Cannonball in the late 1950s, the current is changed and the spheres are no longer formed. The cannonballs are the "Sacred Stones" that the camp was named after.

On the other side of the Cannonball River was a huge camp, as far as I could guess, a mile from one side to the other. I noticed a surveillance airplane flying overhead, circling the big camp. I would find this was a constant presence that people tended to ignore. At times there was also a helicopter hovering over the camp, and often there were drones above us presumably taking photographs. Many of the drones belonged to people in the camp with press credentials. We kept walking, passing many small campsites with more teepees and tents set up along the river, and another largish camp called "Rosebud" which was established by the Lakota people of Rosebud reservation in South Dakota. We came to another checkpoint at a bridge with a paved roadway that crossed the river. There were a few vehicles and many people crossing on foot. I thought it was curious that although the weather was warm and there were no showers in the camps, I did not see anyone in the river washing, swimming, or wading.

On the other side of the bridge, on the north side of the river, there was yet another checkpoint, the official camp exit. As we waved and passed through I could see far ahead that there was an unpaved road with hundreds of flags on both sides of it that represented over 300 Indian tribes and about 100 countries from around the world. Even though Frank and Radjana had been here only two months before, the landscape did not look familiar to them. In September this camp had 500 people living in it. Now there were easily 5,000. My estimate was that the total population of the camps on both sides of the river was somewhere between 7,000 and10,000 people.

We approached what appeared to be another activity center where people were gathered. There was a Sacred Fire burning, the first one that was lit back in April that had been burning continuously. There was an altar with cow skulls, baskets of tobacco, sage, cedar, braids of sweet grass and other ceremonial objects on the northeast side of the fire (later there would be questions about this position… altars were usually placed on the east side of a fire) and about 10 folding chairs encircling it. There was an area that I referred to as "The Stage" where there were three canopies set up in front of a long army tent. There was a man speaking into a microphone connected to an amplified public address system. He was telling a story. When he finished speaking, another man came up and took the microphone. He addressed the crowd as "Relatives," spoke a few words in an Indian language, and then, in English, thanked everyone for being there. Then he said, “We are one family.” I looked around and saw many people with brown skin and long black hair and I got choked up. I wished I could pass a DNA test and be in this family. The microphone was passed around to a few more people who told us we were in ceremony, we were in prayer, and we had to respect and love one another. Furthermore, we were asked to pray for the people who were building the pipeline and for the police who were defending them and reacting with violence toward demonstrators. Instead of “Protesters” he referred to all of us as “Water Protectors.”

Radjana stopped to interview people whenever possible, and we eventually found ourselves at a great Buckminster Fuller-style geodesic dome. Outside the dome was a mobile flatbed unit with an array of solar panels and a full bank of batteries. There were hanging LED lamps inside the dome but I never did find out what else was plugged into this large system which I estimate could generate enough electricity to run a household refrigerator or two throughout the day. Inside the dome a meeting was about to begin. It was a support group for people who had been arrested. We had heard a few horror stories about a recent Action (or was it the recent raid on the North Camp?) where people were arrested and confined in what looked like dog kennels, and women were reportedly strip searched. There were people who had physical and psychological post-traumatic stress symptoms who needed to come forward and be cared for. Radjana went in to collect information for her article. Frank walked with me to the spot where in September they had camped in their vehicle. It was far away from the crowd and near a small creek or pond. I could not see the source of the water. Frank said it was a good place to camp. Curiously, there was a large house on a flatbed truck nearby that I could use as a landmark. It was somewhat isolated, like a cleared cul-de-sac in a field of tall prairie grass. We went back to tell Radjana that we were going back to get the car and bring my camping gear and we would pick her up in about half an hour. We walked back over the bridge to the Sacred Stone Camp. Hungry, I stopped in the kitchen for a bowl full of venison stew left over from lunch. It was very good. I felt a little sad that this was not where I was going to be staying, but it was a place I could explore and spend time at later.

By this time it was late afternoon. Frank and I got into our vehicle and drove back out the way we came in. The road lead us around the small town of Cannon Ball on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation and back past the convenience store where we turned right this time, onto route 1806, and crossed the river on that same bridge we had walked over. Heading north on the road, about a half mile away, there was an official main entrance to the large camp with its own checkpoint guarded by a person who asked if we were new or returning. This was the same dirt road lined with the four-hundred-and-growing flags. We parked and dropped my camping gear at my campsite and walked back to pick up Radjana who was still inside the dome listening to people’s stories. Not wishing to disturb them, Frank gestured to Radjana that we would be waiting outside for her.

In that same instant, a man walked up brandishing a big camera with a long telephoto lens. He was an Indian and I didn’t feel like it was necessary for me to police him about photographing. He asked us “What is going on in here?” I told him it was a meeting for protesters who had been arrested. He stood near us and inquired why we were there. He introduced himself as Frank White Bull, and said that he was on the Standing Rock Tribal Council. He told us that he questioned “all this Green stuff” gesturing to the solar array. He seemed serious, but I couldn't tell if he was. It wasn’t as if we were at a trade show, no one was selling anything, but there were solar panels and wind generators on the site. He said that the stuff was detracting from the main issues: Water and the Children who were not born yet--the Future as it is often referred to by the Indians with the expression "The Seventh Generation." I didn't feel that the “Green stuff” was distracting at all, rather it was powering the camp and serving to demonstrate that oil is not the only way to produce electricity. But he was making his point that he felt that people's focus in the camp had gotten side-tracked. Energy and climate change is not the first issue here; water is. Then he told us that the camp was going to be closed down in a week. Oh, it would take about a month to clear everyone out, but it was not a legal camp and it was not necessary for us to be there. For one thing, the Tribe was paying for our toilets and trash removal. The Standing Rock Tribe would manage the Pipeline issue as a legal one themselves. The effort had been made, and the Dakota Access Pipeline had been legally stopped for now. The current issue was that "business is disregarding government."

"Let Standing Rock handle it, " he said.

I didn't challenge him or ask questions. On the surface, I would have argued that the protests and the subsequent violent police reactions were garnering media attention and support from the public. But to him, I think, it may have seemed an unnecessary waste of time, energy, and resources. I kept trying to second-guess why he was telling us these things; maybe he was trying to test our sincerity. In the very near future I would be able to tell him that by being here I learned a lot about the struggles of the Indians and a lot of other things. I could tell him now that this was a historic camp, that this gathering of people all appreciated his hospitality. He gave us his business card. By this time, Radjana had joined us. She had a press pass and asked White Bull a few questions.

Then he showed us some photographs that he had taken that were stored on his cell phone. They were beautiful and skillfully taken photos; one was of the Milky Way, a bright mass of stars in the night sky, the other was of the green-hued Northern Lights, taken “right from that bridge over there, last month” the same one we had walked over. But we would not see these things in the sky at this time, he told us, because the Dakota Access Pipeline construction site was lit up at night, with bright stadium lights that polluted the night sky in order to discourage protesters from chaining themselves to equipment or other “mischief” on the work site.

My reaction was both disappointment and relief at the same time. My understanding of what White Bull had said was that we were not needed to go on the “Front Line” of protest action, did not have to camp out over the winter, I was not needed for support. But here was my opportunity to learn, help out, and report what the people back home were not seeing because the news was not covering most of what was really at the heart of what was going on. It had taken a lot for me to get here, and I was expecting to take something back with me. "So I should go home?” I asked. White Bull said, “No, you don’t have to go home,” and I thought, but where else can I go now? I was having a vision of roaming around on foot on the Great Plains for the next week. I felt like my whole reason for being was challenged. I was stunned and confused. Two months later I am still wondering what his intention was by imparting this "information" to us; why did he single me out? I wondered who else he might have approached with these questions and information. It was to be my only encounter of this kind during my entire stay.

It was going to take a long time for me to process the words. In those moments, my mind felt poisoned, and I wanted to share what White Bull had said to me with other people. But I did not. I had a feeling that if I did, his words, if repeated, would have had the effect on the camp like an oil leak running over the territory that the Missouri River feeds, all the way down to the Mississippi, and on to the Gulf of Mexico, before it could be stopped and corrected. I asked around if there were Tribal Council members on site that I could talk with. I was also told-- and would have suspected anyway--that there were "plants," and agents provocateurs, and untrue rumors being spread, and that I needed to be aware of these things. I wanted to find out if what he said was for real, that the Indians did not want us there. Everything else he said sounded legitimate, practical, and realistic. I was trying to gauge what he told us and why. Was there division within the Tribe itself about having this pipeline go through? Was there money to be made, if not by the whole Tribe, then possibly by some who had invested in it? These were only my speculations, but I knew nothing. I was I was going to have to keep quiet and listen.

Sundown was approaching and Frank and Radjana walked with me back to my campsite. I took note of landmarks so I would not become lost when I needed to find my way back to my tent alone. My touchstone would be the house on wheels nearby. While finding my way back to my base, I looked around me and I felt like I was on a peninsula covered with two-feet-deep coarse grass and a few mid-sized trees. Other than the nearby body of water, I was pretty much alone with about 75 feet to myself on all sides. I didn't have access to internet mapping at the time, but now I know now that I was camped on the sediment delta of the Cantapeta Creek. There were some wide pathways through the grass that had been made by some kind of vehicle. I hastily set up my tent in the middle of a pathway. My travel companion, Frank, offered me his sleeping bag as an extra, and with some deliberation I took it. I didn't yet know how glad I would be to have it inside my own down sleeping bag. We said good night; my comrades would be back the next day. I rolled out my sleeping bags and put on a sweater, and despite that my flashlight was not working I walked the longish distance, maybe about a quarter mile, back to the center of activity, the Sacred Fire, just to get my thumb on the pulse of things. My psyche felt infected with White Bull’s words and I needed to reconnect. On my way to the fire, I took note of where the “Spiffy Biffs” (the portable toilets) were and inspected them for toilet paper and cleanliness. Everything checked out fine, which was remarkable given how many people were using them.

It was dark by the time I got to the fire. Someone was talking on the microphone over the public address system, which I could see was hooked up by thick wires to a battery bank on another mobile trailer with solar panels. I had located the coffee station, on a couple of long tables about 30 feet away from the Sacred Fire on the west side. I asked about kitchens, where I would find food. I learned about a kitchen called Winona’s “over there behind that brown teepee” where I could get fry bread and native dishes. From the “stage” about 30 feet to the north of the fire, Native persons took turns speaking, making announcements about such things as available rides to Bismarck, found items, lost items, keeping your dogs away from this circle, women please wear skirts, please check in if you are with the press and receive a press pass, please attend the Community Meeting and Orientation at 9:00 a.m. at the Community Hall in the big army tent over there. We were addressed as welcome Relatives; we are all family, thank you for being here to support us; Hello, my name is ___________ and I came out from _________ reservation in ________; prayers, songs, stories. I saw two people under the canopy conversing using their hands, not speaking. Could it be Indian sign language like I saw in the movies when I was a little kid? Often someone took the microphone and introduced themselves as '"Nobody." I was still feeling unsure about what was going on, and after what White Bull had told us, to me everything I was experiencing had taken on an aura of being contrived. I could not shake it but I was still not going to repeat what I had been told. I was standing on the outside of the immediate circle of chairs around the fire, just observing, trying to know my own feelings. I could sense that everyone around me was enjoying a meaningful and connected feeling, and there was an effort to nurture this unity. At the same time I felt like it was O.K. for me to be alone in my skepticism. I noticed an unmistakable style in the way that many American Indians speak when they are delivering a monologue. They take on an air of authority, deliberation, and articulation. They seem to get to the heart of the matter quickly. I had heard Indians speak before at pow-wows, sweat lodges, and in movies. Each speaker ended their soliloquy with “Mitakuye Oyasin,” which means “All My Relations” in the Lakota language. A speaker announced that some runners from Arizona would be arriving on foot in a few hours.

A black woman came into the circle crying. She was very distressed, and I thought I heard her say something about her brother. I felt like she needed help immediately, but I didn't know what was the right thing to do. Someone walked right up to her and put their arms around her and walked her to the fire, and someone gave her their seat. I went behind her chair and put my hands on her shoulders. I don't remember anyone asking her what was wrong, but she stopped crying and everyone gave her their loving attention. I could feel it; everyone cared. I had never experienced anything like that before. In another group circumstance, people might have felt like it was not their business, but in this place, I was finding that none of us were strangers and we were here to care for one another.

Suddenly there was a ruckus around the fire. I was nearby but I did not see what caused it. Someone -- undoubtedly a tribal outsider -- had thrown cremated ashes of his friend into the fire. This person had now desecrated the Sacred Fire and an effort was made to extract the remains from the ashes in the fire. A Native woman exclaimed, "We don't know if this cremated person had been a good person. We don't know what kind of life they led. If they were a bad person, this fire has been desecrated." The person who threw them in had already vanished back out into the camp. The man at the microphone kept asking the person to come forward and collect his friend, repeating, “No, we aren’t going to hurt you, or offend you,” and telling us all that requests for corrections to our behavior were not acts of aggression. I reasoned to myself that whatever the deceased person had been like in life, they were now purer because of being put into the Sacred Fire. But that was just my point of view. I was still an outsider, a colonizer, a settler, and a guest to these kind people who were feeding me, letting me camp with them, giving me coffee and stories and prayers and, most of all, educating me.

I walked from the circle back in the direction of my tent. I stopped by a crowd that had gathered around a big drum where there were people singing in some Indian language. I didn’t ask anything, I just stood and listened. I was not a stranger to Indian drumming and singing, but I am slow to learn songs or I would have been singing along with the strange syllables, melodies, and heart-beat rhythms. Nothing about this small gathering felt artificial. These were Indians who had either come from a few miles away or had traveled a great distance carrying their drum and their songs.

Walking back toward my tent I encountered a group of people set up nearby around a small campfire. I approached them an introduced myself. I said, “Hello, my name is Monica, I am camped here,” and pointed to my tent. I then retired to my tent and changed into my night clothes. I did not fall asleep right away. I could still hear the drumming and singing, and I could hear musicians taking turns at the open microphone which had turned from information and prayers and added entertainment into the mix. I was still feeling like there was something wrong, something unreal and weighing on me, but I eventually fell asleep and slept well. I did not remember having any dreams.

Saturday, November 5, 2016

I was awakened by a loud voice, “KIKTA PO! KIKTA PO! WAKE UP! WARRIORS, SMUDGE YOUR PIPES! CHRISTIANS, POLISH YOUR CROSSES. PRAY! THEY HAVE BEEN UP FOR THREE HOURS ALREADY WORKING ON THAT BLACK SNAKE! KIKTA PO! WAKE UP! IT IS GOING TO BE A GOOD DAY!” The sound was coming through the amplified public address system. The air was cold and it was still dark. I didn’t want to get out of my sleeping bag. I turned on my phone to see what time it was. It was 6:00 a.m. I changed into my day clothes and navigated in the darkness to the Sacred Fire. On my way I passed by the Spiffy Biffs just as a truck pulled up to clean them out. Later I would find that at 6:00 a.m. sharp every day, the toilets were emptied and cleaned and new paper was placed in them, enough to last all day and night. I found then always reasonably clean.

There was a camp set up around the Sacred Fire, that made it like a kind of town square. A big winter army tent on the north side with three canopies connected worked as a kind of stage and shaded a sitting area for elders. On the east side there were open canopies with folding chairs underneath, and on the south side there was a large dry-erase board that served as a message kiosk. There was the coffee station on the west side, with a lattice fence behind it. The coffee was always fresh, if weaker than what I was used to, but with just enough caffeine to keep away pain and fatigue and contribute to our mental clarity. Around our coffee, I was meeting people from all over the world: Maori from New Zealand, a group of founding members from Black Lives Matter, people from Japan and France and Indians -- from India! There were a lot of people newly arriving.

The old man holding the microphone identified himself as a medicine man from Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. He continued by saying morning prayers in Lakota and in English. He thanked the Great Spirit for a new day to make himself into a better person. He sang to the rising sun. He passed the microphone to a Navajo man who had driven out from Oregon, who also prayed in his own native language. Again we were thanked for being there in support, and again told we were all related, and that we were fostering a spirit of forgiveness and respect, and if we had just arrived, to please attend the Community Meeting at 9:00 a.m. at the dome. "Mitakuye Oyasin! Mni Wiconi!" Throughout my stay the cry "Mni Wiconi"--"Water is Life" could be often be heard in sudden bursts of call-and-response throughout the camp.

As the horizon grew pink with the rising sun, the crowd of worshipers (and coffee drinkers) grew. Someone announced that a women’s water ceremony was going to take place at 7:00 a.m. I was going to discover that some events or ceremonies had strict time structures and exact locations, but others did not. Anyway, I was not wearing a watch and seldom turned on my phone. By the time seven o'clock came our crowd had grown to about 200 people. We formed a large circle. A group of women, maybe as many as ten of them dressed in winter jackets and long skirts, went up to the front "stage" area. They began singing a water song in English; one woman carried a hammered copper pitcher. She went around the circle and stood in front of each person and poured a little water into our cupped left hands from which we drank. The water tasted very sweet. I read later on that the tap water at the nearby town of Cannon Ball is also sweet. The taste of the water, as if there had been fresh peaches floating in it, was more reason to protect it. Then the women lined up and we walked down the dirt road with some men following behind to the bank of the Cannonball River, about a quarter mile away, singing along the way, and giving water to people who came up for a handful. Our walking ceremony consisted of about a hundred people. When we got to the bank of the river, the men lined up along both sides of the steep pathway to help the women down the bank to a small dock where the ceremony continued. It was chivalrous and felt so respectful to see these strangers putting out their hands to offer assistance. I have heard that Sioux men are told they have to respect all women. In the line I saw a man who looked like my friend, David, who had died very young, six years ago. I thought of him and his depression and addiction. I wished that he could have been there. In that brief moment I also thought about the suicide epidemic among young people that had taken place not long ago on Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. When we got to the bottom of the bank, we women were each, one at a time, given a small amount of tobacco to sprinkle into the river followed by water poured from the pitcher. Next, men who identified themselves as women, women who identified as men, and people who identified as both or neither were all invited to pour water. As I understood this ceremony, it was to thank the Creator for giving us Water, in an open group setting, in a formal way. Although this ceremony was sexually segregated, both sexes were needed to participate, and there was more than one way for a person to define herself as “female.”

**********************************

After this ceremony was over, I went to Winona’s kitchen for breakfast. I was already finding that I was often not so hungry, and that one small helping of whatever was available two or three times a day was plenty of food to sustain me. When I got back to the main circle I found a table with folding chairs and I thought to sit down to roll a cigarette. I had brought a pouch of organic tobacco with me for the purpose of giving away and for having a smoke myself if I found occasion to sit still for five minutes. An Indian man sitting at the table greeted me, and told me his name was Rudell Bearshirt, that he had come from Wouned Knee on Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. I told him that I had been there twice before and we began talking but before our conversation got deeper, Frank and Radjana showed up. (I never did get to roll that cigarette, but I did manage to connect with Rudell later on Facebook.)

Frank told me that the house that was my landmark was gone! (Where do you move a big house on wheels in the middle of nowhere to? Anywhere, I guess!) We spent the next few hours roaming the camp and found some yurts that had been erected. Radjana conducted a few more interviews while we took turns posing for our own photos to post on Facebook. I picked one for Frank to post of me when he got back to internet lands to let my friends know I was O.K.

The weather was beautifully warm, high in the low seventies and sunny. I was told that usually by this time of year there was snow on the ground. Behind the bulletin board kiosk, there was a large army tent where there was a big stash of winter clothing and blankets being sorted and given out. I was still harboring hope that no one would feel a need to stay the fierce winter. Of course it would be kind of an adventure, but I was feeling that the camp was not going to be sustainable. It was not easy to realistically prepare for the eventual reality of arctic conditions, especially with the deceptive tease of a seemingly everlasting summer.

At noon there was a commotion: People were coming into the camp on horseback. They were Indians and they were headed to the next ceremony to light the 7th Council Fire.

Oceti Sakowin means “Seven Council Fires,” and is the proper name for the people otherwise known as the Sioux. The Akta Lakota Museum website explains, “The original Sioux Tribe was made up of Seven Council Fires. Each of these Council Fires was made up of individual bands, based on kinship, dialect and geographic proximity. Sharing a common fire is one thing that has always united the Sioux people. Keeping of the Peta Wakan (Sacred Fire) was an important activity. On marches coals from the previous council fire were carefully preserved and used to rekindle the council fire at the new campsite.” My sense now is that probably those who came in on horseback were another band of Sioux arriving. The ceremony began with a few people gathering around a fire pit that was in the middle of a ring of teepees. A thousand people gathered in an outer circle. People rode around on horseback on the 20-foot-wide track between the inner and outer circles of people. Everyone was quiet, even the babies. All photography had been strictly forbidden at this ceremony. A drone flew above us. Many people shouted at it and waved it away. Someone at the inner circle began to speak. I had to strain to hear what was being said. Even if I could not hear most of it, I felt like it was an honor just to be present. The fire was lit, I heard a cheer, and saw the smoke rise. People around the fire who had pipes held them up; someone was praying. Soon coming up the pathway there was a parade of children who entered the circle. There were more cheers, and songs, and shaking hands with the youth, and then the pipe carriers came out of the circle to offer us a toke from their pipes. I shared a sacred pipe with probably a hundred of people that day. When the ceremony ended, I found Radjana again and I saw Reverend David McCollum, the man who sat next to me on my plane ride from Denver; he was carrying his peace pole that had come all the way from Japan.

Frank, Radjana and I milled about some more; Radjana continued to interview people, and I followed. Not used to being idle, I was still looking for work to do. Eventually we returned to the car and took a ride to the Prairie Knights Casino, seven miles south, for a buffet supper. While we were having dinner we found that Frank’s phone had internet reception so I turned on my laptop and dashed off a message. I began, “What a great time and place to be in History!” Frank disappeared for a short while and came back to the table and tossed me a hundred dollar bill he had just won on a slot machine. He possibly didn’t realize how much I needed and appreciated the money. I found a pay phone in the lobby where for a dollar I could make an outgoing four-minute call and Frank told me that it was easy to get rides to and from the Casino. Plenty of people at the camp went there. Those who took a room let many others come to share their shower, internet and other amenities. It was probable that I would be going back there over the next few days. I made a couple of phone calls from Frank’s cell phone to let people at home know I had arrived.

We drove back to camp and I said goodbye to Frank and Radjana. They were flying back home to Arizona the next day. I crawled into my tent and although it was still early I went right to sleep.

Sunday November 6, 2016

Of course I woke up early. It was still dark and although I was used to waking up at 4:00 a.m. back east, I was in a different time zone and had no idea what time it was. Still in my pajamas, I walked over to the Sacred Fire where there were a few men sitting in the circle of folding chairs around the fire. Unfortunately there were very bright stadium-type lights shining in our direction from the pipeline construction site which was about three-quarters of a mile away. Many of the more distant and dimmer stars were obscured by the glare, but the position of bright Orion was still a reliable way to tell the time at night. We took turns guessing what time it might be, and then someone looked at his cell phone and told us it was 2:50 a.m. That seemed kind of early until we realized that this was the night when we set back the clock an hour for the winter, and the cell phone reset itself automatically, so in keeping with my own circadian rhythm I was actually right on schedule. The men expressed how tired they were and how they all wanted to go to sleep, but keeping the Sacred Fire going has to be done by a designated Firekeeper. A Firekeeper was the only person allowed to place logs on the fire ensuring that people treated the fire respectfully and that they didn’t throw anything foreign into it. The only exceptions were for tobacco, cedar, sage or sweetgrass, while praying.

A Firekeeper also kept everyone mindful that nothing bad was said in front of the fire, that we kept our intentions as well as our language pure: no gossip, no politics, no cussing. I told them that I was an old Girl Scout, knew how to keep a fire going, and was familiar with ceremonies. I volunteered myself for the role of Firekeeper, and they accepted. To me, this was a great honor, and was something that I had always wanted to do. They all left to go to sleep. I saw how quickly firewood was being consumed so I took a conservation approach, allowing the fire to burn down a little before adding another split log. I ended up being mostly alone under the stars for a few hours, just feeding the fire and feeling grateful to be there. Occasionally someone came and sat. A few people asked me, “Who is keeping the fire?” I was joined by a woman who told me her name was April and that she was from the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in Montana. She was very friendly and identified herself as Sioux; she had driven all day and night to get here and had not yet been to bed. I asked her about life on her reservation, and she told me there was a problem there with methamphetamine abuse. It was a story I was going to hear again from other Indians from other places. I asked April one of the few questions I asked during my entire visit: did the Sioux have a story about how the human beings lost their fur? I had been thinking about what could be the possible biological reasons we humans had evolved to not have body hair to keep us warm like other animals did. The story might be told that either through trickery, arrogance, gambling, or some other means, they lost their coat. April said that no, there was no such story. We talked a little before she eventually left the fire to go to sleep. After some time had passed, an Indian man inserted himself between me and the fire, moved some logs around, and threw a big handful of cedar needles into the fire, accidentally dropping a glove in as he did so. As the glove started to smolder I pointed to it and he pulled it out; then, just as quickly as he had come into the circle, he left. I reasoned that he probably thought that the fire was not being tended to just because it was not blazing and because there was a lone white woman sitting by. He had simply made an assumption and didn’t think to ask if anyone was keeping the fire.

Eventually the old Lakota Medicine man came into the circle, and he asked me, “Who is keeping the fire?” “I am,” I replied. He chuckled. Soon by asking “Is the microphone on?” he revealed himself as the person who calls out the morning wake-up prayers. A man with technical experience appeared and turned on the electricity that came from the solar battery bank. The coldest part of night was noticeably just before sunrise. There seemed to be an extra gust of cold wind that I felt just as the old medicine man was thanking the Creator for a New Day. Gradually and steadily the wind was, in fact, increasing. A small crowd was gathering; someone came to the fire to gather some coals to light another fire for making fresh coffee. He introduced himself to me as the Firekeeper and he thanked me for keeping it going. I took leave for the latrine. On the Spiffy Biffs door was a leaflet that read that there would be a Peace Walk to Mandan at 8:00 a.m. today. The Peace Walk was intended to surround the Morton County courthouse and to forgive the police force for its brutality during a raid on a Water Protector’s camp on October 27. I wanted to be a part of the walk. In spite of my intention to come here and be helpful building winter housing, I was finding that there was a lot going on to witness, be part of, and learn from. I didn't know anything yet about that particular raid, but there had been enough police brutality in the news that I thought it could have been a collective forgiveness gesture. I wanted to walk in support of the group to see how forgiveness looks in action. I also thought it could be a way to learn how to heal some wounds from my own past and a way to move forward in whatever I might be doing in my future.

I went back to my tent to change into my day clothes, and on my way not far from my tent I noticed a sweat lodge, a dome shaped structure covered with tarps with a fire ring a few feet in front of it. This would be one of my landmarks, and I wondered if I would be welcome to join in a sweat bath. After I had changed my clothes and got back to the main area, I found that I had missed my ride with the cars going out to Mandan. Someone made an announcement that a hunter had killed and brought in a deer, and there would be a demonstration on how to skin and butcher the animal outside the refrigerated rations tent. He also announced that a local farm family killed and donated a pig. I stayed at the circle as the women prepared to perform the water ceremony as they had the day before, but did not follow them down to the river this time.

It was my third day in camp and it had been highly advised that everyone attend the daily 9 a.m. Community Meeting and a workshop on non-violent Direct Action. The first meeting was supposed to take place in a big Army tent that was the designated Community Center, but I was re-directed to the geodesic dome, which was big enough to comfortably hold well over a hundred people. A small crowd had gathered outside the dome. After about a hundred of us seated ourselves inside, our facilitator, Johnnie, opened the session by thanking us for being there, told us how the formal process of these meetings worked, that each session began with a prayer and ended with a prayer. He asked us all to agree with that precept and went around the circle to find out if anyone had an objection to it. How many of us were newcomers? We raised our hands showing there were about 40 of us who had arrived in the last few days attending the meeting. How many planning to stay the winter, raise hands, please? At least 10 indicated they were planning to stay. He told us about a place they called Facebook Hill where there were better prospects of receiving cell phone signals and internet, and that in a few days the camp was going to have its own internet connection. He told us where to go to be issued a media pass if we represented the press; he explained there was a school if we had kids who need to be in school. He suggested going out and picking up trash, volunteering to help out at kitchens, and helping to erect winter tents. There would be a “Wellbriety” meeting at the Emotional Wellness teepee. Wellbriety, I learned, is a movement much like the 12-step addiction recovery programs “advocating for Native American Recovery and Wellness.” All of us newcomers were then sent out to receive orientation instructions in another place inside the aforementioned big army tent they called Community Hall.

I left with the large group of newcomers to attend that next meeting. The facilitators were Occupy Wall Street-trained people, who gave us a crash-course on racism, colonialism, cultural appropriation, and to correct other misconceptions we might have. I had been to meetings with seasoned activists before, but here we were all basically being reminded that if we were not natives, then it would be disrespectful to dress and behave as if we were. Wearing feathers was mentioned as being frowned upon. I didn't ask any questions, but I should have. Inspired by the pretty ribbon shirts I had seen Indian men wearing at pow-wows I’d made one for myself. I brought it with me on this trip; to me it is much more than just a decorative piece of clothing. I endowed it with spiritual intention while I was sewing it, and I wore it on my own personal vision quest years earlier. I didn't ask if I could wear it, I just didn’t. I wasn't going to take the chance if it could possibly make the wrong statement.

The facilitators asked us to introduce ourselves and to explain a little about why we came here. It was made clear that those of us who had come to participate in the Direct Actions that we should expect to be arrested and that it was mandatory to attend a Direct Action training. We should attend training even if we were not going to be involved on the front lines of protest. They suggested that we also go to a few other meetings, one on media, one on legal and arrest issues.

On our way out, I briefly connected with a few people who wanted to attend the Direct Action meeting. I went in search of some labor to do while I waited for the time of the training. There was a big wooden shed nearby being built to shelter a water supply truck for the winter. It had windows facing south, using passive solar principles so it would be more likely to stay above freezing inside. The construction people were busy but were short on tools so they couldn’t use my help. I wandered. The clothing donation tent was very busy sorting through donations. I rifled through the sweaters and found a really nice periwinkle-colored fleece jacket that fit me. It was what I needed to wear now that the wind was increasing and although there was no mirror to admire myself in, I knew that the color was perfect. I picked up a broad scarf, too, big enough to cover my head and neck. Whatever clothing surplus there was, items not appropriate for the winter needs of the camp, were being bagged and sent out to other communities on the Reservation.

I passed by the tent where the deer was being skinned and butchered. It was splayed on a white plastic tarp on the ground. There was a person demonstrating with a knife, pointing out its parts, and about 5 people gathered around watching. It reminded me of a biology lab, or a hospital surgery.

Across the road there was a roped-off enclosure with all kinds of stuff in it. They were the possessions of people who had been arrested in the October 27 raid or who fled because of it. The “North Camp” also known as the "1851 Treaty Camp" had been erected in direct line of the pipeline construction on land purchased only a month before by Dakota Access Pipeline. During the raid, peaceful demonstrators were praying as the police sprayed pepper spray and made arrests. The protesters’ abandoned belongings, tents, clothing, sleeping bags, had been rescued and here were being neatly folded and sorted until the owners came to claim them. I gave a little help there, but the wind was growing stronger and changing directions, so it was difficult to fold things.

It was then time for the Direct Action meeting and I went looking for the place where it was supposed to have been held. Directions were vague; there were no longer signs pointing the way and I had to ask for directions. When I got to the assigned location I found the meeting had been canceled. Places and times for some meetings seemed changeable, but I still always managed to show up in time for another experience.

Since I happened to be near to my own tent, I thought to just hang out by myself for a while. I stopped and stood still near the sweat lodge that was on my way, sending in my own silent prayers. A white woman walked up to me told me not to stand there. I didn't ask why. At my site, I found that the strong wind had blown my tent into a slanting position, so I removed the poles and flattened it so that it would not be blown away completely. Nearby I saw a small rodent, a mouse, a vole, or a shrew nibbling on grass seed on a stalk. I got up close to watch it, but I scared it, and it burrowed into some flattened grass, but not very deep. I reached out and touched its back between the blades of grass with my finger, and stroked its fur. This little guy is the real native here, I thought, who might set the example on how to really prepare for winter.

After I had dismantled my tent, I looked across the creek, past a big grassy field, at a hill about a half mile away. I saw that the crest of the hill was covered with a line of uniformly dressed military-outfitted police. Below, there were about 30 people climbing up the hill. I saw a line of people on horseback riding up behind and around the people climbing. I wished that I had brought binoculars and a telephoto lens for my camera. I could see well enough to guess what was going on. There were demonstrators attempting to occupy the hill. From behind me I heard someone at the open microphone shouting, “Tell those people to get back here! This is not a sanctioned action!” and I saw people rushing off on foot to the hill to bring the protesters down, but not before I saw the police, or whoever they were, rolling canisters of tear gas down the hill, upwind from the people.

It was not clear to me what a “sanctioned action” meant; who did the sanctioning? Who was invited or who would one ask if one wished to volunteer to go along? How were the rest of us in the camp to know, if only to pray for this demonstration? There were only a total of five of us watching the unsanctioned Action unfold from a spot that seemed to have the clearest view. There were both an airplane and helicopter circling the hill and I took many photos. Within a half hour there were several pickup trucks full of people returning to the camp from the Action. They all looked triumphant, but I still don’t know what had happened. I read later that the hill, a place called Turtle Island, was a historic burial site in need of protection from the pipeline construction. Later I was told that whenever there was a Direct Action planned, the trainings would be canceled, and my guess is that because the teachers would be at the Action. An Action was often a group of Indian Water Protectors going to a site to pray.