Truthseeker, Changemaker, Pilgrim on the Road, Student of The Way

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

A Diplomat Defects From the Kremlin over Ukraine

The Sources of Russian Misconduct

A Diplomat Defects From the Kremlin

By Boris Bondarev

Foreign Affairs

November/December 2022

For three years, my workdays began the same way. At 7:30 a.m., I woke up, checked the news, and drove to work at the Russian mission to the United Nations Office in Geneva. The routine was easy and predictable, two of the hallmarks of life as a Russian diplomat.

читать статью по-русски (Read in Russian)

February 24 was different. When I checked my phone, I saw startling and mortifying news: the Russian air force was bombing Ukraine. Kharkiv, Kyiv, and Odessa were under attack. Russian troops were surging out of Crimea and toward the southern city of Kherson. Russian missiles had reduced buildings to rubble and sent residents fleeing. I watched videos of the blasts, complete with air-raid sirens, and saw people run around in panic.

As someone born in the Soviet Union, I found the attack almost unimaginable, even though I had heard Western news reports that an invasion might be imminent. Ukrainians were supposed to be our close friends, and we had much in common, including a history of fighting Germany as part of the same country. I thought about the lyrics of a famous patriotic song from World War II, one that many residents of the former Soviet Union know well: “On June 22, exactly at 4:00 a.m., Kyiv was bombed, and we were told that the war had started.” Russian President Vladimir Putin described the invasion of Ukraine as a “special military operation” intended to “de-Nazify” Russia’s neighbor. But in Ukraine, it was Russia that had taken the Nazis’ place.

“That is the beginning of the end,” I told my wife. We decided I had to quit.

Resigning meant throwing away a twenty-year career as a Russian diplomat and, with it, many of my friendships. But the decision was a long time coming. When I joined the ministry in 2002, it was during a period of relative openness, when we diplomats could work cordially with our counterparts from other countries. Still, it was apparent from my earliest days that Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs was deeply flawed. Even then, it discouraged critical thinking, and over the course of my tenure, it became increasingly belligerent. I stayed on anyway, managing the cognitive dissonance by hoping that I could use whatever power I had to moderate my country’s international behavior. But certain events can make a person accept things they didn’t dare to before.

The invasion of Ukraine made it impossible to deny just how brutal and repressive Russia had become. It was an unspeakable act of cruelty, designed to subjugate a neighbor and erase its ethnic identity. It gave Moscow an excuse to crush any domestic opposition. Now, the government is sending thousands upon thousands of drafted men to go kill Ukrainians. The war shows that Russia is no longer just dictatorial and aggressive; it has become a fascist state.

But for me, one of the invasion’s central lessons had to do with something I had witnessed over the preceding two decades: what happens when a government is slowly warped by its own propaganda. For years, Russian diplomats were made to confront Washington and defend the country’s meddling abroad with lies and non sequiturs. We were taught to embrace bombastic rhetoric and to uncritically parrot to other states what the Kremlin said to us. But eventually, the target audience for this propaganda was not just foreign countries; it was our own leadership. In cables and statements, we were made to tell the Kremlin that we had sold the world on Russian greatness and demolished the West’s arguments. We had to withhold any criticism about the president’s dangerous plans. This performance took place even at the ministry’s highest levels. My colleagues in the Kremlin repeatedly told me that Putin likes his foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, because he is “comfortable” to work with, always saying yes to the president and telling him what he wants to hear. Small wonder, then, that Putin thought he would have no trouble defeating Kyiv.

The war shows that decisions made in echo chambers can backfire.

The war is a stark demonstration of how decisions made in echo chambers can backfire. Putin has failed in his bid to conquer Ukraine, an initiative that he might have understood would be impossible if his government had been designed to give honest assessments. For those of us who worked on military issues, it was plain that the Russian armed forces were not as mighty as the West feared—in part thanks to economic restrictions the West implemented after Russia’s 2014 seizure of Crimea that were more effective than policymakers seemed to realize.

The Kremlin’s invasion has strengthened NATO, an entity it was designed to humiliate, and resulted in sanctions strong enough to make Russia’s economy contract. But fascist regimes legitimize themselves more by exercising power than by delivering economic gains, and Putin is so aggressive and detached from reality that a recession is unlikely to stop him. To justify his rule, Putin wants the great victory he promised and believes he can obtain. If he agrees to a cease-fire, it will only be to give Russian troops a rest before continuing to fight. And if he wins in Ukraine, Putin will likely move to attack another post-Soviet state, such as Moldova, where Moscow already props up a breakaway region.

There is, then, only one way to stop Russia’s dictator, and that is to do what U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin suggested in April: weaken the country “to the degree that it can’t do the kinds of things that it has done in invading Ukraine.” This may seem like a tall order. But Russia’s military has been substantially weakened, and the country has lost many of its best soldiers. With broad support from NATO, Ukraine is capable of eventually beating Russia in the east and south, just as it has done in the north.

If defeated, Putin will face a perilous situation at home. He will have to explain to the elite and the masses why he betrayed their expectations. He will have to tell the families of dead soldiers why they perished for nothing. And thanks to the mounting pressure from sanctions, he will have to do all of this at a time when Russians are even worse off than they are today. He could fail at this task, face widespread backlash, and be shunted aside. He could look for scapegoats and be overthrown by the advisers and deputies he threatens to purge. Either way, should Putin go, Russia will have a chance to truly rebuild—and finally abandon its delusions of grandeur.

PIPE DREAMS

I was born in 1980 to parents in the middle strata of the Soviet intelligentsia. My father was an economist at the foreign trade ministry, and my mother taught English at the Moscow State Institute of Foreign Relations. She was the daughter of a general who commanded a rifle division during World War II and was recognized as a “Hero of the Soviet Union.”

We lived in a large Moscow apartment assigned by the state to my grandfather after the war, and we had opportunities that most Soviet residents did not. My father was appointed to a position at a joint Soviet-Swiss venture, which allowed us to live in Switzerland in 1984 and 1985. For my parents, this time was transformative. They experienced what it was like to reside in a wealthy country, with amenities—grocery carts, quality dental care—that the Soviet Union lacked.

As an economist, my father was already aware of the Soviet Union’s structural problems. But living in western Europe led him and my mother to question the system more deeply, and they were excited when Mikhail Gorbachev launched perestroika in 1985. So, it seemed, were most Soviet residents. One didn’t have to live in western Europe to realize that the Soviet Union’s shops offered a narrow range of low-quality products, such as shoes that were painful to wear. Soviet residents knew the government was lying when it claimed to be leading “progressive mankind.”

Russia’s bureaucracy discourages independent thought.

Many Soviet citizens believed that the West would help their country as it transitioned to a market economy. But such hopes proved naive. The West did not provide Russia with the amount of aid that many of its residents—and some prominent U.S. economists—thought necessary to address the country’s tremendous economic challenges. Instead, the West encouraged the Kremlin as it quickly lifted price controls and rapidly privatized state resources. A small group of people grew extremely rich from this process by snapping up public assets. But for most Russians, the so-called shock therapy led to impoverishment. Hyperinflation hit, and average life expectancy went down. The country did experience a period of democratization, but much of the public equated the new freedoms with destitution. As a result, the West’s status in Russia seriously suffered.

It took another major hit after NATO’s 1999 campaign against Serbia. To Russia, the bombings looked less like an operation to protect the country’s Albanian minority than like aggression by a large power against a tiny victim. I vividly remember walking by the U.S. embassy in Moscow the day after a mob attacked it and noticing marks left by paint that had been splattered against its walls.

As the child of middle-class parents—my father left the civil service in 1991 and started a successful small business—I experienced this decade of turbulence mostly secondhand. My teenage years were stable, and my future seemed fairly predictable. I became a student at the same university where my mother taught and set my sights on working in international affairs as my father had. I benefited from studying at a time when Russian discourse was open. Our professors encouraged us to read a variety of sources, including some that were previously banned. We held debates in class. In the summer of 2000, I excitedly walked into the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for an internship, ready to embark on a career I hoped would teach me about the world.

My experience proved disheartening. Rather than working with skilled elites in stylish suits—the stereotype of diplomats in Soviet films—I was led by a collection of tired, middle-aged bosses who idly performed unglamorous tasks, such as drafting talking points for higher-level officials. Most of the time, they didn’t appear to be working at all. They sat around smoking, reading newspapers, and talking about their weekend plans. My internship mostly consisted of getting their newspapers and buying them snacks.

I decided to join the ministry anyway. I was eager to earn my own money, and I still hoped to learn more about other places by traveling far from Moscow. When I was hired in 2002 to be an assistant attaché at the Russian embassy in Cambodia, I was happy. I would have a chance to use my Khmer language skills and studies of Southeast Asia.

Since Cambodia is on the periphery of Russia’s interests, I had little work to do. But living abroad was an upgrade over living in Moscow. Diplomats stationed outside Russia made much more money than those placed domestically. The embassy’s second-in-command, Viacheslav Loukianov, appreciated open discussion and encouraged me to defend my opinions. And our attitude to the West was fairly congenial. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs always had an anti-American bent—one inherited from its Soviet predecessor—but the bias was not overpowering. My colleagues and I did not think much about NATO, and when we did, we usually viewed the organization as a partner. One evening, I went out for beers with a fellow embassy employee at an underground bar. There, we ran into an American official who invited us to drink with him. Today, such an encounter would be fraught with tension, but at the time, it was an opportunity for friendship.

Yet even then, it was clear that the Russian government had a culture that discouraged independent thought—despite Loukianov’s impulses to the contrary. One day, I was called to meet with the embassy’s number three official, a quiet, middle-aged diplomat who had joined the foreign ministry during the Soviet era. He handed me text from a cable from Moscow, which I was told to incorporate into a document we would deliver to Cambodian authorities. Noticing several typos, I told him that I would correct them. “Don’t do that!” he shot back. “We got the text straight from Moscow. They know better. Even if there are errors, it’s not up to us to correct the center.” It was emblematic of what would become a growing trend in the ministry: unquestioned deference to leaders.

YES MEN

In Russia, the first decade of the twenty-first century was initially hopeful. The country’s average income level was increasing, as were its living standards. Putin, who assumed the presidency at the start of the millennium, promised an end to the chaos of the 1990s.

And yet plenty of Russians grew tired of Putin during the aughts. Most intellectuals regarded his strongman image as an unwelcome artifact of the past, and there were many cases of corruption among senior government officials. Putin responded to investigations into his administration by cracking down on free speech. By the end of his first term in office, he had effectively taken control of all three of Russia’s main television networks.

Within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, however, Putin’s early moves raised few alarms. He appointed Lavrov to be foreign minister in 2004, a decision that we applauded. Lavrov was known to be highly intelligent and have deep diplomatic experience, with a track record of forging lasting relationships with foreign officials. Both Putin and Lavrov were becoming increasingly confrontational toward NATO, but the behavioral changes were subtle. Many diplomats didn’t notice, including me.

Even limited displays of opposition make Moscow nervous.

In retrospect, however, it’s clear that Moscow was laying the groundwork for Putin’s imperial project—especially in Ukraine. The Kremlin developed an obsession with the country after its Orange Revolution of 2004–5, when hundreds of thousands of protesters prevented Russia’s preferred candidate from becoming president after what was widely considered to be a rigged election. This obsession was reflected in the major Russian political shows, which started dedicating their primetime coverage to Ukraine, droning on about the country’s supposedly Russophobic authorities. For the next 16 years, right up to the invasion, Russians heard newscasters describe Ukraine as an evil country, controlled by the United States, that oppressed its Russian-speaking population. (Putin is seemingly incapable of believing that countries can genuinely cooperate, and he believes that most of Washington’s closest partners are really just its puppets—including other members of NATO.)

Putin, meanwhile, continued working to consolidate power at home. The country’s constitution limited presidents to two consecutive terms, but in 2008, Putin crafted a scheme to preserve his control: he would support his ally Dmitry Medvedev’s presidential candidacy if Medvedev promised to make Putin prime minister. Both men followed through, and for the first few weeks of Medvedev’s presidency, those of us at the foreign ministry were uncertain which of the two men we should address our reports to. As president, Medvedev was constitutionally charged with directing foreign policy, but everybody understood that Putin was the power behind the throne.

We eventually reported to Medvedev. The decision was one of several developments that made me think that Russia’s new president might be more than a mere caretaker. Medvedev established warm ties with U.S. President Barack Obama, met with American business leaders, and cooperated with the West even when it seemed to contradict Russian interests. When rebels tried to topple the regime of Muammar al-Qaddafi in Libya, for example, the Russian military and foreign ministry opposed NATO efforts to establish a no-fly zone over the country. Qaddafi historically had good relations with Moscow, and our country had investments in Libya’s oil sector, so our ministry didn’t want to help the rebels win. Yet when France, Lebanon, and the United Kingdom—backed by the United States—brought a motion before the UN Security Council that would have authorized a no-fly zone, Medvedev had us abstain rather than veto it. (There is evidence that Putin may have disagreed with this decision.)

But in 2011, Putin announced plans to run for president again. Medvedev—reluctantly, it appeared—stepped aside and accepted the position of prime minister. Liberals were outraged, and many called for boycotts or argued that Russians should deliberately spoil their ballots. These protesters made up only a small part of Russia’s population, so their dissent didn’t seriously threaten Putin’s plans. But even the limited display of opposition seemed to make Moscow nervous. Putin thus worked to bolster turnout in the 2011 parliamentary elections to make the results of the contest seem legitimate—one of his earlier efforts to narrow the political space separating the people from his rule. This effort extended to the foreign ministry. The Kremlin gave my embassy, and all the others, the task of getting overseas Russians to vote.

I worked at the time in Mongolia. When the election came, I voted for a non-Putin party, worrying that if I didn’t vote at all, my ballot would be cast on my behalf for Putin’s United Russia. But my wife, who worked at the embassy as chief office manager, boycotted. She was one of just three embassy employees who did not participate.

A few days later, embassy leaders looked through the list of staff who cast ballots in the elections. On being named, the other two nonvoters said they were not aware that they needed to participate and promised to do so in the upcoming presidential elections. My wife, however, said that she did not want to vote, noting that it was her constitutional right not to participate. In response, the embassy’s second-in-command organized a campaign against her. He shouted at her, accused her of breaking discipline, and said that she would be labeled “politically unreliable.” He described her as an “accomplice” of Alexei Navalny, a prominent opposition leader. After my wife didn’t vote in the presidential contest either, the ambassador didn’t talk to her for a week. His deputy didn’t speak to her for over a month.

BREAKING BAD

My next position was in the ministry’s Department for Nonproliferation and Arms Control. In addition to issues related to weapons of mass destruction, I was assigned to focus on export controls—regulations governing the international transfer of goods and technology that can be used for defense and civilian purposes. It was a job that would give me a clear view of Russia’s military, just as it became newly relevant.

In March 2014, Russia annexed Crimea and began fueling an insurgency in the Donbas. When news of the annexation was announced, I was at the International Export Control Conference in Dubai. During a lunch break, I was approached by colleagues from post-Soviet republics, all of whom wanted to know what was happening. I told them the truth: “Guys, I know as much as you do.” It was not the last time that Moscow made major foreign policy decisions while leaving its diplomats in the dark.

Among my colleagues, reactions to the annexation of Crimea ranged from mixed to positive. Ukraine was drifting Westward, but the province was one of the few places where Putin’s mangled view of history had some basis: the Crimean Peninsula, transferred within the Soviet Union from Russia to Ukraine in 1954, was culturally closer to Moscow than to Kyiv. (Over 75 percent of its population speaks Russian as their first language.) The swift and bloodless takeover elicited little protest among us and was extremely popular at home. Lavrov used it as an opportunity to grandstand, giving a speech blaming “radical nationalists” in Ukraine for Russia’s behavior. I and many colleagues thought that it would have been more strategic for Putin to turn Crimea into an independent state, an action we could have tried to sell as less aggressive. Subtlety, however, is not in Putin’s toolbox. An independent Crimea would not have given him the glory of gathering “traditional” Russian lands.

Creating a separatist movement in and occupying the Donbas, in eastern Ukraine, was more of a head-scratcher. The moves, which largely took place in the first third of 2014, didn’t generate the same outpouring of support in Russia as did annexing Crimea, and they invited another wave of international opprobrium. Many ministry employees were uneasy about Russia’s operation, but no one dared convey this discomfort to the Kremlin. My colleagues and I decided that Putin had seized the Donbas to keep Ukraine distracted, to prevent the country from creating a serious military threat to Russia, and to stop it from cooperating with NATO. Yet few diplomats, if any, told Putin that by fueling the separatists, he had in fact pushed Kyiv closer to his nemesis.

The West’s 2014 sanctions substantially weakened the Russian military.

My diplomatic work with Western delegations continued after the Crimean annexation and the Donbas operation. At times, it felt unchanged. I still had positive relations with my colleagues from the United States and Europe as we worked productively on arms control issues. Russia was hit with sanctions, but they had a limited impact on Russia’s economy. “Sanctions are a sign of irritation,” Lavrov said in a 2014 interview. “They are not the instrument of serious policies.”

But as an export official, I could see that the West’s economic restrictions had serious repercussions for the country. The Russian military industry was heavily dependent on Western-made components and products. It used U.S. and European tools to service drone engines and motors. It relied on Western producers to build gear for radiation-proof electronics, which are critical for the satellites Russian officials use to gather intelligence, communicate, and carry out precision strikes. Russian manufacturers worked with French companies to get the sensors needed for our airplanes. Even some of the cloth used in light aircraft, such as weather balloons, was made by Western businesses. The sanctions suddenly cut off our access to these products and left our military weaker than the West understood. But although it was clear to my team how these losses undermined Russia’s strength, the foreign ministry’s propaganda helped keep the Kremlin from finding out. The consequences of this ignorance are now on full display in Ukraine: the sanctions are one reason Russia has had so much trouble with its invasion.

The diminishing military capacity did not prevent the foreign ministry from becoming increasingly belligerent. At summits or in meetings with other states, Russian diplomats spent more and more time attacking the United States and its allies. My export team held many bilateral meetings with, for instance, Japan, focused on how our countries could cooperate, and almost every one of them served as an opportunity to say to Japan, “Don’t forget who nuked you.”

I attempted some damage control. When my bosses drafted belligerent remarks or reports, I tried persuading them to soften the tone, and I warned against warlike language and constantly appealing to our victory over the Nazis. But the tenor of our statements—internal and external—grew more antagonistic as our bosses edited in aggression. Soviet-style propaganda had fully returned to Russian diplomacy.

HIGH ON ITS OWN SUPPLY

On March 4, 2018, former Russian double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia were poisoned, almost fatally, at their home in the United Kingdom. It took just ten days for British investigators to identify Russia as the culprit. Initially, I didn’t believe the finding. Skripal, a former Russian spy, had been convicted for divulging state secrets to the British government and sent to prison for several years before being freed in a spy swap. It was difficult for me to understand why he could still be of interest to us. If Moscow had wanted him dead, it could have had him killed while he was still in Russia.

My disbelief came in handy. My department was responsible for issues related to chemical weapons, so we spent a good deal of time arguing that Russia was not responsible for the poisoning—something I could do with conviction. Yet the more the foreign ministry denied responsibility, the less convinced I became. The poisoning, we claimed, was carried out not by Russia but by supposedly Russophobic British authorities bent on spoiling our sterling international reputation. The United Kingdom, of course, had absolutely no reason to want Skripal dead, so Moscow’s claims seemed less like real arguments than a shoddy attempt to divert attention away from Russia and onto the West—a common aim of Kremlin propaganda. Eventually, I had to accept the truth: the poisonings were a crime perpetrated by Russian authorities.

Many Russians still deny that Moscow was responsible. I know it can be hard to process that your country is run by criminals who will kill for revenge. But Russia’s lies were not persuasive to other countries, which decisively voted down a Russian resolution before the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons meant to derail the prominent intergovernmental organization’s investigation into the attack. Only Algeria, Azerbaijan, China, Iran, and Sudan took Moscow’s side. Sure enough, the investigation concluded that the Skripals had been poisoned by Novichok: a Russian-made nerve agent.

Moscow wanted to be told what it hoped to be true—not what was actually happening.

Russia’s delegates could have honestly conveyed this loss to their superiors. Instead, they effectively did the opposite. Back in Moscow, I read long cables from Russia’s OPCW delegation about how they had defeated the numerous “anti-Russian,” “nonsensical,” and “groundless” moves made by Western states. The fact that Russia’s resolution had been defeated was often reduced to a sentence.

At first, I simply rolled my eyes at these reports. But soon, I noticed that they were taken seriously at the ministry’s highest levels. Diplomats who wrote such fiction received applause from their bosses and saw their career fortunes rise. Moscow wanted to be told what it hoped to be true—not what was actually happening. Ambassadors everywhere got the message, and they competed to send the most over-the-top cables.

The propaganda grew even more outlandish after Navalny was poisoned with Novichok in August 2020. The cables left me astonished. One referred to Western diplomats as “hunted beasts of prey.” Another waxed on about “the gravity and incontestability of our arguments.” A third spoke about how Russian diplomats had “easily nipped in the bud” Westerners’ “pitiful attempts to raise their voices.”

Such behavior was both unprofessional and dangerous. A healthy foreign ministry is designed to provide leaders with an unvarnished view of the world so they can make informed decisions. Yet although Russian diplomats would include inconvenient facts in their reports, lest their supervisors discover an omission, they would bury these nuggets of truth in mountains of propaganda. A 2021 cable might have had a line explaining, for instance, that the Ukrainian military was stronger than it was in 2014. But that admission would have come only after a lengthy paean to the mighty Russian armed forces.

The disconnect from reality became even more extreme in January 2022, when U.S. and Russian diplomats met at the U.S. mission in Geneva to discuss a Moscow-proposed treaty to rework NATO. The foreign ministry was increasingly focused on the supposed dangers of the Western security bloc, and Russian troops were massing on the Ukrainian border. I served as a liaison officer for the meeting—on call to provide assistance if our delegation needed anything from Russia’s local mission—and received a copy of our proposal. It was bewildering, filled with provisions that would clearly be unacceptable to the West, such as a demand that NATO withdraw all troops and weapons from states that joined after 1997, which would include Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Poland, and the Baltic states. I assumed its author was either laying the groundwork for war or had no idea how the United States or Europe worked—or both. I chatted with our delegates during coffee breaks, and they seemed perplexed as well. I asked my supervisor about it, and he, too, was bewildered. No one could understand how we would go to the United States with a document that demanded, among other things, that NATO permanently close its door to new members. Eventually, we learned the document’s origin: it came straight from the Kremlin. It was therefore not to be questioned.

I kept hoping that my colleagues would privately express concern, rather than just confusion, about what we were doing. But many told me that they were perfectly content to embrace the Kremlin’s lies. For some, this was a way to evade responsibility for Russia’s actions; they could explain their behavior by telling themselves and others that they were merely following orders. That I understood. What was more troubling was that many took pride in our increasingly bellicose behavior. Several times, when I cautioned colleagues that their actions were too abrasive to help Russia, they gestured at our nuclear force. “We are a great power,” one person said to me. Other countries, he continued, “must do what we say.”

CRAZY TRAIN

Even after the January summit, I didn’t believe that Putin would launch a full-fledged war. Ukraine in 2022 was plainly more united and pro-Western than it had been in 2014. Nobody would greet Russians with flowers. The West’s highly combative statements about a potential Russian invasion made clear that the United States and Europe would react strongly. My time working in arms and exports had taught me that the Russian military did not have the capability to overrun its biggest European neighbor and that, aside from Belarus, no outside state would offer us meaningful support. Putin, I figured, must have known this, too—despite all the yes men who shielded him from the truth.

The invasion made my decision to leave ethically straightforward. But the logistics were still hard. My wife was visiting me in Geneva when the war broke out—she had recently quit her job at a Moscow-based industrial association—but resigning publicly meant that neither she nor I would be safe in Russia. We therefore agreed that she would travel back to Moscow to get our kitten before I handed in my papers. It proved to be a complex, three-month process. The cat, a young stray, needed to be neutered and vaccinated before we could take him to Switzerland, and the European Union quickly banned Russian planes. To get from Moscow back to Geneva, my wife had to take three flights, two cab rides, and cross the Lithuanian border twice—both times on foot.

In the meantime, I watched as my colleagues surrendered to Putin’s aims. In the early days of the war, most were beaming with pride. “At last!” one exclaimed. “Now we will show the Americans! Now they know who the boss is.” In a few weeks, when it became clear that the blitzkrieg against Kyiv had failed, the rhetoric grew gloomier but no less belligerent. One official, a respected expert on ballistic missiles, told me that Russia needed to “send a nuclear warhead to a suburb of Washington.” He added, “Americans will shit their pants and rush to beg us for peace.” He appeared to be partially joking. But Russians tend to think that Americans are too pampered to risk their lives for anything, so when I pointed out that a nuclear attack would invite catastrophic retaliation, he scoffed: “No it wouldn’t.”

The only thing that can stop Putin is a comprehensive rout.

Perhaps a few dozen diplomats quietly left the ministry. (So far, I am the only one who has publicly broken with Moscow.) But most of the colleagues whom I regarded as sensible and smart stuck around. “What can we do?” one asked. “We are small people.” He gave up on reasoning for himself. “Those in Moscow know better,” he said. Others acknowledged the insanity of the situation in private conversations. But it wasn’t reflected in their work. They continued to spew lies about Ukrainian aggression. I saw daily reports that mentioned Ukraine’s nonexistent biological weapons. I walked around our building—effectively a long corridor with private offices for each diplomat—and noticed that even some of my smart colleagues had Russian propaganda playing on their televisions all day. It was as if they were trying to indoctrinate themselves.

The nature of all our jobs inevitably changed. For one thing, relations with Western diplomats collapsed. We stopped discussing almost everything with them; some of my colleagues from Europe even stopped saying hello when we crossed paths at the United Nations’ Geneva campus. Instead, we focused on our contacts with China, who expressed their “understanding” about Russia’s security concerns but were careful not to comment on the war. We also spent more time working with the other members of the Collective Security Treaty Organization—Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan—a fractured bloc of states that my bosses loved to trot out as Russia’s own NATO. After the invasion, my team held rounds and rounds of consultations with these countries that were focused on biological and nuclear weapons, but we didn’t speak about the war. When I talked with a Central Asian diplomat about supposed biological weapons laboratories in Ukraine, he dismissed the notion as ridiculous. I agreed.

A few weeks later, I handed in my resignation. At last, I was no longer complicit in a system that believed it had a divine right to subjugate its neighbor.

SHOCK AND AWE

Over the course of the war, Western leaders have become acutely aware of Russia’s military’s failings. But they do not seem to grasp that Russian foreign policy is equally broken. Multiple European officials have spoken about the need for a negotiated settlement to the war in Ukraine, and if their countries grow tired of bearing the energy and economic costs associated with supporting Kyiv, they could press Ukraine to make a deal. The West may be especially tempted to push Kyiv to sue for peace if Putin aggressively threatens to use nuclear weapons.

But as long as Putin is in power, Ukraine will have no one in Moscow with whom to genuinely negotiate. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs will not be a reliable interlocutor, nor will any other Russian government apparatus. They are all extensions of Putin and his imperial agenda. Any cease-fire will just give Russia a chance to rearm before attacking again.

There’s only one thing that can really stop Putin, and that is a comprehensive rout. The Kremlin can lie to Russians all it wants, and it can order its diplomats to lie to everyone else. But Ukrainian soldiers pay no attention to Russian state television. And it became apparent that Russia’s defeats cannot always be shielded from the Russian public when, in the course of a few days in September, Ukrainians managed to retake almost all of Kharkiv Province. In response, Russian TV panelists bemoaned the losses. Online, hawkish Russian commentators directly criticized the president. “You’re throwing a billion-ruble party,” one wrote in a widely circulated online post, mocking Putin for presiding over the opening of a Ferris wheel as Russian forces retreated. “What is wrong with you?”

Putin responded to the loss—and to his critics—by drafting enormous numbers of people into the military. (Moscow says it is conscripting 300,000 men, yet the actual figure may be higher.) But in the long run, conscription won’t solve his problems. The Russian armed forces suffer from low morale and shoddy equipment, problems that mobilization cannot fix. With large-scale Western support, the Ukrainian military can inflict more serious defeats on Russian troops, forcing them to retreat from other territories. It’s possible that Ukraine could eventually best Russia’s soldiers in the parts of the Donbas where both sides have been fighting since 2014.

Should that happen, Putin would find himself in a corner. He could respond to defeat with a nuclear attack. But Russia’s president likes his luxurious life and should recognize that using nuclear weapons could start a war that would kill even him. (If he doesn’t know this, his subordinates would, one hopes, avoid following such a suicidal command.) Putin could order a full-on general mobilization—conscripting almost all of Russia’s young men—but that is unlikely to offer more than a temporary respite, and the more Russian deaths from the fighting, the more domestic discontent he will face. Putin may eventually withdraw and have Russian propagandists fault those around him for the embarrassing defeat, as some did after the losses in Kharkiv. But that could push Putin to purge his associates, making it dangerous for his closest allies to keep supporting him. The result might be Moscow’s first palace coup since Nikita Khrushchev was toppled in 1964.

If Putin is kicked out office, Russia’s future will be deeply uncertain. It’s entirely possible that his successor will try to carry on the war, especially given that Putin’s main advisers hail from the security services. But no one in Russia commands his stature, so the country would likely enter a period of political turbulence. It could even descend into chaos.

Outside analysts might enjoy watching Russia undergo a major domestic crisis. But they should think twice about rooting for the country’s implosion—and not only because it would leave Russia’s massive nuclear arsenal in uncertain hands. Most Russians are in a tricky mental space, brought about by poverty and huge doses of propaganda that sow hatred, fear, and a simultaneous sense of superiority and helplessness. If the country breaks apart or experiences an economic and political cataclysm, it would push them over the edge. Russians might unify behind an even more belligerent leader than Putin, provoking a civil war, more outside aggression, or both.

If Ukraine wins and Putin falls, the best thing the West can do isn’t to inflict humiliation. Instead, it’s the opposite: provide support. This might seem counterintuitive or distasteful, and any aid would have to be heavily conditioned on political reform. But Russia will need financial help after losing, and by offering substantial funding, the United States and Europe could gain leverage in a post-Putin power struggle. They could, for example, help one of Russia’s respected economic technocrats become the interim leader, and they could help the country’s democratic forces build power. Providing aid would also allow the West to avoid repeating its behavior from the 1990s, when Russians felt scammed by the United States, and would make it easier for the population to finally accept the loss of their empire. Russia could then create a new foreign policy, carried out by a class of truly professional diplomats. They could finally do what the current generation of diplomats has been unable to—make Russia a responsible and honest global partner.

BORIS BONDAREV worked as a diplomat in the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 2002 to 2022, most recently as a counsellor at the Russian Mission to the United Nations Office in Geneva. He resigned in May to protest the invasion of Ukraine.

0 notes

Photo

The Manufacturing Renaissance Agenda to Build Back Better

Creating Manufacturing Renaissance Councils: A renaissance in manufacturing requires strong and vibrant organizations gathered in strong public/private coalitions that understand, support, and defend the new responsibilities and the new roles that are required for success.

We support strong unions, strong community and faith-based organizations, strong management associations, and strong government that are gathered in Manufacturing Renaissance Councils that guide, support, and mobilize public opinion for the Manufacturing Renaissance Agenda and its programs. We deeply believe that these coalitions are more powerful than the sum of their parts.

Impact of the deindustrialization of America: In the 1950s, manufacturing represented 27% of GDP. We had an expanding economy, and a broad-based middle class although still anchored in discrimination by race and gender. By the late 1970s, we began to witness the rapid destruction of our industrial base with the loss of millions of companies and millions of jobs. This decline is a major source of growing income inequality, little to no progress in alleviating poverty, and increasing instability in all aspects of life. Today, manufacturing constitutes only 12% of US GDP.

A Foundation for Development: Manufacturing is central to the health of our society. It provides good, family-supporting jobs paying $84,000 a year including benefits. It creates more jobs in the economy than any other sector, creating 5 other jobs in the economy on average—far more than service or retail sector jobs. These are often good union jobs. A growth in manufacturing can be a tide that lifts all boats including communities, local government, companies, unions, and civic organizations of all types. It can be at the heart of the compounding and intersecting challenges of our time, especially climate change, wealth inequality, and discrimination based on color, gender, and identity.

“...Better:” We embrace the slogan of President Biden of “Build Back Better.” We must “Build Back” our manufacturing sector. But this must be done in a way that is “Better” than in the past when BIPOC as well as women were last hired and first fired and then disproportionately affected by de-industrialization; and when employees were excluded from the critical decisions in the productive process. Embracing inclusion and empowerment of BIPOC people, employees, and women in all aspects of manufacturing should be our competitive advantage.

A Green Economy/A Green Society: We place a manufacturing renaissance at the heart of legislation to address Climate Change and the environmental crisis. Only the manufacturing sector can create the products and processes that will achieve our environmental goals. Our goal is 0 emissions. There must be a dramatic increase in funding for research and product development explicitly tied to climate change. As important is a just transition for workers and communities most affected by environmental racism and the need to shift away from carbon intensive production and processes.

Rebuilding manufacturing becomes:

The path for BIPOC to join the Climate Change movement knowing that it’s premised on their inclusion; and

The path for the Green and progressive movement to see the importance and possibilities in manufacturing and re-building inner city communities.

We call for:

A High Road Industrial Policy--Inclusion & Industry 4.0:

1. Manufacturing must represent 20% of US GDP by 2035.

2, Government must provide for equivalent investment in inclusion as in technology.

3. We bring employers, labor unions, community organizations, religious organizations, and government to work together in coalition to promote Inclusion & Industry 4.0 policies.

4. We encourage participatory management as well as employee ownership.

5. Manufacturing will help build our communities and restore the environment.

Industrial Retention: We must:

1, Close the skills gap. Millions of jobs are going unfilled due to the lack of exposure, education and training of young people denying our manufacturing companies the talent they need to compete in the global economy.

2. Proactively reach out to smaller companies to identify problems and provide assistance before they become a crisis through the creation of Early Warning Networks.

3. Assist employees as well as Black, Latinx, Indigenous and other people of color entrepreneurs to purchase companies facing a succession challenge.

Education and training: We need:

1. Expanded programs from pre-school to graduate school in all aspects of manufacturing including production, product development, engineering, management, and entrepreneurship; and

2. Sectoral partnerships between industry and community that focus on racial equity, wrap around and support services, and training including but not limited to apprenticeship.

3. Driving equity in manufacturing: Federal manufacturing programs like those we propose, the Manufacturing Extension Partnership, Manufacturing USA and others must have explicit goals around diversity, equity, and inclusion, including tracking services by race and mandated partnerships with HBCUs and other Minority Serving Institutions.

April 4 2021

Dan Swinney, Manufacturing Renaissance www.mfgren.org

David Robinson, Manufacturing Renaissance, www.mfgren.org

Alan Minsky, Progressive Democrats of America, https://pdamerica.org/

Bob Creamer, Democracy Partners, https://democracypartners.com/

Andy Stettner, The Century Foundation, https://tcf.org/

Teresa Cordova, Great Cities Institute, University of IL, https://greatcities.uic.edu/

Michael Bennett, African American Institute for Leadership and Policy, https://theaalpi.org/

Tim Wright, Quintairos, Prieto Wood & Boyer, https://www.qpwblaw.com/

Thomas Hanna, Democracy Collaborative, https://democracycollaborative.org/

0 notes

Photo

INSTANT ANALYSIS: My Two Cents

The Three-Cornered Fight

By Carl Davidson

Keep On Keepin’ On

As I watched Trump leaving in the Marine One helicopter, my day was already made. Anything else was gravy. I’ll admit to a few tears—J-lo doing Woody’s Guthrie’s ‘This Land is Your Land’ and the magnificent poet Amanda Gorman ( I didn’t learn until later she practiced hard to overcome her speech impediment to deliver it). But I‘ll put up front what we’ll face in the coming period—a complicated, three-cornered (at least) series of battles.

First, the GOP cabal in the anti-fascist battle took a hard hit, but they are far from out. About 10 in the Senate and 120 fascist-populist enablers remain in the Congress, and many more in 50 statehouses. This is one corner.

The second is our corner, Bernie in the Senate, now boosted up to Chair of the Senate Budget Committee, a powerful spot. In the House of Congress, we have the AOC ‘Squad’ now expanded, and a tougher Congressional Progressive Caucus. All this gives us some clout, but far from hegemony.

President Biden is the third corner, along with his Third Way Centrists, Blue Dogs, and the few GOPers he will win over. He hit the ground running today restoring the Paris Accords, giving a small modicum of student debt relief, and help to the dreamers. But Biden faces not only the ‘uncivil war’ with the right he wants to stop (we can mostly back him here) but also his ‘cascading crises,' four of them—the virus pandemic, a gutted economy, ongoing climate change damage to our habitat, and ongoing racialized injustices. He has at least identified them correctly.

But on each one, there will be a stingy neoliberal approach and a more full-throated progressive approach to meeting and solving them. On these, if we can't find common ground and unity, we will have to fight it out. We will win some, we will get lousy compromises on some, and we will lose some. Mostly, we will do well first to follow Bernie's and AOC’s lead. And second, we need to build up local and state-wide left, anti-fascist voting blocs, uniting around Medicare for All, changes in a racialized justice system, and a Green New Deal.

International policy, finally, will be a hot point. Biden is already moving on China and Venezuela in negative ways, and he should reverse Trump’s stupid designation of Cuba as a ‘terrorist’ state. We have to demand a foreign policy based on noninterference, mutual assistance, and peaceful co-existence. It will require winning some unity in our own peace and solidarity movements on these points. Let’s get started.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Book Review: Globalization, Police and Fascism

The Global Police State

By William I. Robinison

London: Pluto Press, 2020

190 pp. Paper $22.68.

Reviewed Jerry Harris

Leftlinks

In the American Revolution Paul Revere famously rode his horse through sleepy New England towns, clanging a bell and warning everyone that British troops were on the march. For the past decade William Robinson has been on a similar mission, alerting all who would listen to the dangers of a rising police state. With the publication of his new book he brings together all the major elements of his analysis in a tightly woven presentation. As Robinson writes; 'I want to develop the concept of global police state to identify more broadly the emerging character of the global economy and society as a repressive totality whose logic is a much economic and cultural as it is political.' (p. 3).

After the introduction the book is organized into four chapters filled with hard hitting data. These are:

1) Global Capitalism and its Crisis;

2) Savage Inequalities: The Imperative of Social Control;

3) Militarized Accumulation and Accumulation by Repression; and

4) The Battle for the Future.

His thesis, in simplified terms, is that the capitalist crisis of accumulation results in a large impoverished surplus population that needs to be controlled through a police state which also provides an outlet for surplus capital to be invested. This ruling class bloc is lead by the most reactionary fraction of the transnational capitalist class that creates a social base by using nationalist rhetoric. But this narrative is limited to the political and ideological sphere, and rarely impedes on transnational economic interests.

Robinson's starting point is an examination of the transnational capitalist class (TCC) as the hegemonic fraction of global capitalism. But global capitalism suffers from the crisis of over accumulation which develops from the never ending drive to lower costs, particularly the cost of labor. This takes place through defeating unions, seeking lower wages in the Global South, and the precariatization of labor. Another essential element is replacing labor with technology, which in turn increases unemployment. But as large sections of the working class are pushed into insecurity and unable to buy all that's produced, capitalists need to find other avenues to invest their accumulated wealth. This leads directly to financialization, a process in which trillions are poured into

speculative ventures, debt, derivatives and a plethora of financial markets bringing unimagined wealth to a few, while widening the ranks of those impoverished. Moreover, computerized finance produces trillions in value with a fraction of the labor that was necessary in the old industrial economy. All this would have been virtually impossible to construct without the digital revolution. As Robinson points out “The tech sector becomes a layer that sits across the entire economy” (p. 36), linking finance, media and the military. Not only providing the equipment that runs the global economy, but also tying Silicon Valley to finance capital and military contracts.

Such an economy has created a world labor force in which half the urban population is precarious, and one-third are locked out of work in any given period of time. This vast precariat and surplus population presents a constant danger to the TCC, a danger which must be contained and controlled. To do so the TCC greatly expands the military and other repressive tools and institutions. This not only provides a method of control, but also new areas for investments and profits where over accumulated capital can find a home. Consequently, the path of neoliberal globalization has lead inexorability towards a police state and neo- fascism.

Militarized and repressive accumulation are at the heart of Robinson’s analysis, as it ties together both the need for social control with the core economic strategy of the TCC. As the author states “that unprecedented global inequalities can only be sustained by ubiquitous systems of social control and repression (and) it becomes equally evident that …the TCC has acquired a vested interest in war, conflict, and repression as a means of accumulation” (p. 72). From here Robinson amasses a body of evidence and data to trace the economic size and growth of the defense industry, weapon sales, privatized military organizations, the security industry, surveillance capitalism, the prison-industrial complex and the repressive treatment of migrants and refugees. All this is tied to both the tech industry and finance capital to present a hegemonic bloc wedded to the development of a globalized police state.

This brings us to the last chapter in which Robinson delves more deeply into a Gramscian analysis of hegemonic blocs and their social base. To exercise hegemony the ruling class needs political legitimacy gained through material rewards and ideology. This provides a large and solid base of support, with repressive exclusion for those unwilling or unable to join the system. But as the circle of poverty and instability grows reliance on coercive control comes to

dominate. However, even a police state needs a degree of political support. Unable to provide the same level of material rewards as the Keynesian state, the authoritarian capitalist bloc turns to nationalist and racist appeals and militaristic culture. As Robinson points out the police state project; “hinges on the psychosocial mechanism of displacing mass fear and anxiety at a time of acute capitalist crisis towards scapegoated communities such as immigrants, Muslims, refugees” and a long list of others (p. 117-118). Robinson sees Trump’s populism as “almost entirely symbolic.” Essentially an attempt to appease his angry social base with political rhetoric and an ideological smokescreen. But this presents a fundamental contradiction within the authoritarian hegemonic bloc because the “pretense of economic nationalism disrupts global supply chains and undermines TCC interests (opening) up severe splits in ruling blocs, erodes the ruling groups’ capacity to rule, and heightens the political crisis” (p. 126).

Such instability opens up alternative political paths. But Robinson has little hope or confidence in capitalist reformers. Instead he calls for a revitalized international left forming a broad anti-fascist alliance, but one in which the working class has leadership. That necessitates organization and a clear revolutionary project, and the author urges the formation of a new left international. Whatever the road forward is, Robinson has offered one of the best analysis of the grave dangers we face. His book is not an academic exercise, but a tool in the fight against barbarism. All those involved in the struggle for a better future need to read this book.

Jerry Harris is the executive director of the Global Studies Association. [email protected]

0 notes

Photo

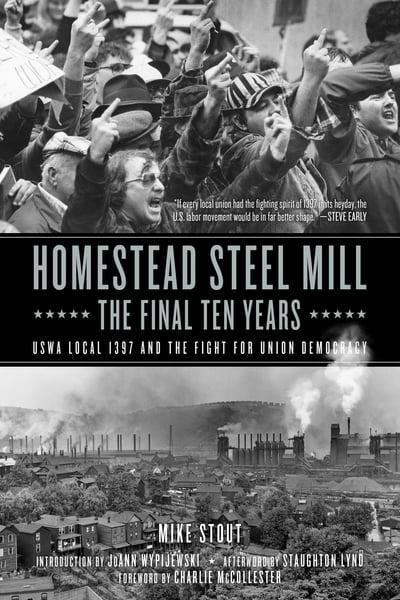

Book Review: Mike Stout’s ‘Homestead Steel Mill’ Is a Manual for Organizers

Homestead Steel Mill: The Final Ten Years

USWA Local 1397 and the Fight for Union Democracy

By Mike Stout

PM Press 2020

By Carl Davidson

Keep on Keepin’ On

Mike Stout’s remarkable new book of a recent large-scale class battle in Western PA can be read in many ways. First, it’s a history of Homestead steelworkers in the last years of their battles to improve their conditions and save their jobs. It’s also Stout’s personal autobiography of a working-class youth radicalized by the 1960s and 1970s and the culture of rebellion of which he was a part. Then one can read it as a fine example of sociological investigation and economic analysis of the Pittsburgh region.

All those brief summations are fine. But most of all, within all these, Stout has written an organizing manual for radicalizing workers of any age embedded in large manufacturing industries. Despite relative declines, these still exist in the Rust Belt and elsewhere. Unfortunately, the current younger workers in them have never been in a union and only know about them from the lore passed down by fathers and grandfathers. Thus nearly all of them are in dire need of new crews of organizers like Mike Stout--or who at least have studied this book.

What makes Stout’s narrative unique is the quality of his personal commitment. In the 1970s, thousands of radicalized young college students, with or without degrees, went into the factories to organize ‘for the revolution.’ A few did well; most did not. But Stout was not one of these. Getting into the mill and the struggle there was a step up for him, as an unemployed kid from Kentucky trying to make a living as a political rock and roller and folk singer. He desperately needed a day job, and getting into Homestead mill enabled him to do both, however hard the work. He had more in common with the returning Vietnam vets in the mill than transplanted student radicals, not that he lacked respect for the latter.

This is not to say that the thousands of workers in a four-mile-long mill were monolithic. Far from it. Stout goes on at length throughout the book describing rivalries between a dozen nationalities, between races and sexes, generations, skilled and lesser skilled, and old timers and newcomers.

‘As the book’s title suggests, however, Stout sticks to his outline of ‘the last ten years,’ although it stretches a bit longer to include the aftermath. At the start, hardly anyone had a premonition of what was in store for them—the mills had been there as long as anyone could remember, and thus they would continue into the future. What was different was the owners were squeezing the workers harder, and after the Red purges of the 1950s, the unions had grown cozier with the bosses, The stage was set for rank and file insurgency, and this is the setting Stout entered as a new hire.

Nearly everyone in Western PA gets a nickname in high school or at work. Stout was no different, and his fellow workers tagged him ‘Kentucky’ and it stuck. He laid low in his early months, trying to find the best ways to survive and thrive working rotating shifts. The older ‘beer and a shot’ workers in the bars raised an eyebrow because he only drank red wine, but he slid in easy with the younger crowd that liked their alcohol combined with reefer. Mainly Stout had his eye on a crane operating job, but he was amazed at the skills—and luck—involved to do it safely. It would take some time. But early on, he got the reputation as a guy who resisted any crap thrown at him by foremen. This led him to find a small group of militant workers seeking to find a way to change the union into an instrument that would fight for them.

They certainly had a history behind them. Homestead was a center for more than 150,000 steelworkers in Western PA and neighboring states. The ‘Battle of Homestead’ of the previous century had been compared to the Paris Commune, and fierce battles of the Steel Workers Organizing Committee in the 1930s had helped found the CIO. FDR’s Labor Secretary, Frances Perkins, visited the Homestead Works, but forbidden to speak on the grounds. Legend has it that she spotted a US flag flying over a post office, made her way there, where she delivered a fiery speech for the rights of labor.

Stout quickly joined up with the rank-and-file group and started planning a campaign. Perhaps their most important early project was to start a plant-wide newspaper, the 1397 Rank and Filer. Stout’s description of its impact and evolution over the years is an instructive tale of how a newspaper can become a ‘collective organizer.’ When an organization had to spread the word over a mill measured in square miles, and where thousands of workers on one end often knew little of events on another, it was indispensable. Moreover, the mill was subdivided into what Spout called ‘feudal fiefdoms’ ruled by petty tyrants with divide and rule tactics

The workers also had to have access to the newspaper and to trust it. So it was open to letters, hand-drawn cartoons, and a popular feature called ‘Plant Plague’ that expose the injustices and pure nastiness of plant foremen. It also published studies of the union contract and the misdeeds of the union officials, all with an eye toward replacing them.

After many skirmishes, it paid off. The Local 1397 Rank and File Caucus eventually evolved from a militant minority to a progressive majority of union members and took over the local. There’s a long story in between, of course, but it’s worth reading Stout’s account in full.

For his own role, Stout appears to have made several wise decisions early on and stuck to them. One was to keep his connection with the editorial group that put out the newspaper, both before and after the takeover of the local. The other was to avoid seeking a top post for himself. Early on, because of his unflinching willingness to not only defend workers with a beef, but also to get them involved in their own defense, he rose to a more organic leader. This meant he became a ‘griever’ or grievanceman, eventually becoming a chief griever, and one of the best of them. It might take years, but Stout often won his cases. Even if a worker died, he persisted, winning benefits for surviving families.

Another reason for Stout’s influence was practicing a consistent left politics, expressed in his own terms, and never trying to hide his values, despite red-baiting and other attempts at personal slanders. He offers several accounts of standing up against racism and sexism when it erupted among the workers themselves, as well as used as a weapon by supervisors and other higher-ups.

Stout was known as a socialist inside and outside the mill. At one point, he was connected with the Revolutionary Union, an early 1970s Marxist-Leninist nationwide group. It had rank-and-file union newspapers in other cities and industries, but Stout detached from it as it became too sectarian for his taste.

But what is powerfully portrayed in the book is Stout’s astute combinations of politics with culture. Its pages are replete with the lyrics of dozens of songs written for working-class battles in Homestead and beyond. Together with them are stories of how music was used for firing up picket lines or finding creative ways to raise money. It helped that Stout was good at it, not just knowing a few old labor songs, but pulling together full-fledged rock band performances.

By the middle of the book, you get pulled into the sense of impending doom shared among the workers. What we now know as ‘the Rust Belt’ was being born. Faced with competition abroad and poor management at home, neoliberal capitalism tore up its postwar ‘social contracts.’ Corporate boardrooms closed plants here and shipped production offshore in search of cheaper labor. In some cases, it used modernization to cut workforces by half or more, while keeping production at old levels.

At this point, both Local 1397 and the USW generally learned that unions could not survive without wider allies. Stout unfolds the saga of the nationwide movements in the 1980s and 1990s against plant closings. Workers sought community and government partners in an effort to save profitable businesses by innovation and reorganization, or even in some cases, attempting to buy out and take over the plants themselves.

None of these paid off much, at least in the Homestead area. Stout describes somes of the proposed deals as ‘Last Suppers before our execution.’ But he nonetheless tells a tale of the value of persistence, where he continued to carry on battles and win major grievances for workers even after the plant was closed, the union reduced to a shell and Stout himself among the unemployed. He soldiered on by forming a union print shop as a workers coop, as well as making a few bucks playing concerts here and abroad.

Despite this grim conclusion, ‘Homestead Steel Mill: The Last Ten Years’ is a hopeful book. It draws positive lessons from defeats, showing the need for wider and more protracted political strategies. It’s not enough to press liberals to do good things; workers need a vision of taking power themselves. And the lessons of its victories stand out as well. Workers can win when they are well-organized, well-informed, and well-inspired. They need a culture of solidarity and mutual aid to fight for what belongs to them, not only the part, but the whole deal. You can buy the book HERE

1 note

·

View note

Photo

INSTANT ANALYSIS, NIGHT FOUR. My two cents.

By Carl Davidson

This was a night for our full conflicted consciousness to be on display. It opened with the joyful music from African American culture, with music from the church blending into modern rap and hip hop, calling out hope for the future. It was quickly followed by Rep Debra Anne Haaland of New Mexico, a member of the state's Laguna people, who migrated there and built their pueblos long before Columbus, Naturally, she was backing Biden, but simply that she stood there spoke volumes more.

The session ended with Biden asking God to bless our troops, a departure from the usual phrase, reminding us that his was a military family, as well as one rooted in the working class. (He calls it the 'middle class', a term I can't stand. It reduces us to consumers. If you asked a guy from my hometown, Aliquippa, in Western PA, when he was at work, what class he was in, he'd look at his hands and say 'working class'. But if you asked him the same question on Sunday, he'd look around his yard and porch furniture and say 'middle class,' dividing him from the 'lower class.'). Gramsci's 'conflicted consciousness' spotlights it all.

Those contradictions are part of the story of my life. When I grew up in the 1950s, we didn't call it 'the military,' we called it 'the service.' I saw too many high school buddies drawn into it, then sent to Vietnam, perhaps to recover later from physical wounds, but not the psychic ones. I was one who refused, and dedicated 15 years of my life, through battles large and small, to bring it to an end. Part of the reason was that my eyes were opened by the other battles praised that night, from John Lewis eulogies to hearing Ella Baker quoted as a speech opening. I knew Lewis personally, who stayed with me a few days at Penn State and inspired me to do my 'tour of duty' in the Deep South. Ella Baker was the mother and teacher of us all in those days. So for me, I have bitter memories of the Democratic party of those years, of the escalation in Vietnam and the sellouts of Blacks in Atlantic City and Mississippi.

I have family members in 'the service' today--Coast Guard, Marines, Homeland Security. They chose their careers for honorable reasons, and did well in them. I knew Illinois' s Sen.Tammy Duckworth when she first ran for office. So when images of our soldiers in Iraq crossed the screen tonight, there was a void. Those of us who rose up against that invasion and ongoing occupation knew it well. It was a stupid, brutal, unjust and imperialist venture, with Trump even bragging just today, 'I got the oil, We'll keep the oil.' I'd rather Duckworth had her two legs. And while Biden went on about his support for military families, which I understand, I also noticed a silence. He refused to mention his support for that war, backing the GOP, even though his own party was divided, starting with the heroic stand of Rep, Barbara Lee.

The story of Biden's empathy is authentic. I think it largely rises from his successful but still evident battle with his stutter. And the story shown of how he helped the young boy working on the same problem was heartwarming. No one can ignore the contrast with Trump on camera mocking a reporter with a stutter and a crippled hand. It tells you all you need to know about Trump, even though there is much more pond scum where that came from. The Democratic party is deeply conflicted this round; the GOP, on the other hand, has devolved into a fascist death cult devoid of shame. So I will give Biden a vote to defeat the fascist cult, but I don't kid myself that the Dems are one happy family. Far from it.

Biden ended with a line from the Irish poet looking for a day when hope and history would rhyme. It's a good line, but my guess it will arrive in a way unforeseen. The virus, together with all our other conflicts, has made the world, for the first time, view us not with fear but with pity. It's the end of the era of the America of Empire, and perhaps a beginning for the era of an America of popular democracy. If so, there will be much more room for poets and less for soldiers.

0 notes

Photo

INSTANT ANALYSIS, NIGHT THREE. My two cents.

By Carl Davidson

This evening was a tribute and a celebration of women, not only in politics but in the entire life of the country. We expect it of Democrats these days, in the wake of the risings of the 1960s and 70s. It wasn't always so. But I have always admired strong and unbowed women, most likely because my mother was one. Not only her but also her sisters and all the tough working-class women of my extended family.

I loved Elizabeth Warren's story about her Aunt Bea, who came to her rescue when the burdens of the house and children were too heavy. It reminded me of my Great Grandma Minnie, who showed up on the doorstep with two suitcases when my Mom was due to deliver a new brother or sister, or when all of us kids were down with whooping cough. There are women like these throughout the working class, and to see them paid some due respect was heartening, even if many Democrats, not to mention the GOP, had to be pulled here with their heels dragging.

The key political point of the night was made by Barack Obama. It was a dramatic warning that American democracy, even with the flaws of its class blinders, was at stake. He stretched it to new dimensions, and I could hear the tropes of John Dewey's philosophical exploration of a democracy of mass participation in his phrasing. He also warned us about the little cop of cynicism that resides between our ears, the one that whispers two lies, nothing changes and you have no power anyway. The truth is everything changes and with solidarity, we have immense power. After outlining for us all of the virtues of democracy American-style, he coldly told us a chilling truth about Trump and his crew: they don't believe in any of it. And it's up for grabs unless we act. Therein was a warning of the fascist danger.

Kamala Harris wrapped up the night. Some on the left, in my opinion, misjudge her, thinking she's a rightwing cop because she was a DA and an Attorney General. To be polite, it's reductionist. As Senator, she voted 92% of the time with Bernie Sanders. As a prosecutor, she made some decisions worthy of criticism. But she also took on finance capital and organized crime, winning billions for homeowners and others. My hero in Congress, Barbara Lee, thinks well of her. Harris softened the stern persona she revealed when slicing up William Barr in Congress, and she touched my bases by naming Fannie Lou Hamer and SNCC's Diane Nash as inspirations. My point? I don't think her story is finished and we will see what unfolds.

0 notes

Photo

INSTANT ANALYSIS, NIGHT TWO: My two cents.

By Carl Davidson

This session's task was mainly to humanize the Democrats and Biden and his family. It did a fairly effective job of it, including things that I don't support. I'm talking about the section on national security and international relations toward the end. Biden's presidency will work to restore Cold War hegemonism with the US as 'leader of the free world.' That was the content of John Kerry and Colin Powell's short speeches, both underscoring how Trump has wrecked the earlier US position in favor of a weird alliance with Putin, the UAE and Turkey. Trump's dalliance with Kim Jong Un defies rationality of any sort, as does his trade war with China. The real question is whether anyone can make US imperialism 'normal' again. I think not, and even Biden will have to adapt to a multipolar world in some new way. The only contrast to this stance was implied in Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's brief speech nominating Bernie. She touched on decolonization and a different relationship with other peoples: "...a movement striving to recognize and repair the wounds of racial injustice, colonization, misogyny, and homophobia, and to propose and build reimagined systems of immigration and foreign policy that turn away from the violence and xenophobia of our past." (Something positive could also be said for both Kerry and Powell's presence, in that it served as a warning to Trump that the Pentagon, State Dept and intelligence agencies were not likely to brook any nonsense about his refusing to leave office when defeated). I enjoyed the roll call most. Rather than droning on a packed arena floor, we got to see real people in their states and territories, and something about them. Best was the shoutout of tallies for Bernie and Joe. Of course, Bernie lost, but for me, as a socialist, to hear that we had chalked up a sizable minority of delegates, and hearing them repeated from all over, was an inspiration for the struggle to continue. Bernie will be emeritus, of course, as will I. But AOC and 'The Squad', and the Bernie union people, will carry on through the next rounds, gaining strength, until a new First Party emerges. One last point for those in my age cohort. Listening to Caroline Kennedy, I recalled the little girl playing with John-John on the White House lawn. Then I looked at her son, and unmistakably saw how different he looked from his Mom, but clearly, he was the Grandson of Jacqueline Bouvier.

0 notes

Photo

INSTANT ANALYSIS: MY TWO CENTS...

By Carl Davidson

Between Bernie Sanders and Michelle Obama, we got the solid call for a popular front against fascism. Bernie ran down the platform of the left, but tailored it to unite with the many in the center and some among the right who are deserting the GOP as well.

Michelle Obama, however, hit the ball out of the park with bases loaded, with a speech that both dug into the emotional depth of progressive politics and voiced razor-like and understated takedowns of Trump. One of my favorites, which I've often expressed myself, is that he's just 'in way over his head' and not up for the job. She also issued a dark warning, as did Bernie: if you think it can't get worse, it can, and it will if Trump is not crushed in November.

I also thought the format came off decently even if a bit hokey at points. (It was the first time out for a virtual convention.) The music was excellent, and I teared up when John Prine was singing, himself a victim of the virus. The brief statements from the frontline medical workers and survivors were moving and brilliant. And throughout, great care was taken to reveal and celebrate the rainbow diversity of our working class and our people generally. I know very well the nature of our Democratic party, and the class character of those who control its central levers. But this round, this is the hand we're dealt, and I'm not one to fold. We'll see what follows over the next few days.

0 notes

Link

I STARTED AS A PHYSICS MAJOR INTERESTED IN THE STARS. But with the felt danger of nuclear war at the Cuba crisis, I started questioning it, then got into the philosophy of science, then the history of philosophy, then from Hegel into Marx. I stayed there since Marx helped me understand the working class I came from and how we could get free. But it was never enough. Kerouac's Dharma Bums, a serious book on Buddhism, got me deeper into it as well, and I studied with a Zen Monk in Nebraska and read Henry Bugbee, a Daoist with American characteristics, in Montana from Penn State. Now with this little piece, I see I was on to something, and I was not alone.

0 notes

Link

The Biggest Guns: The Social Base of Militarism

By Carl Davidson

ONE TRILLION DOLLARS. FOR A GROUP OF PLANES THAT CAN'T FLY HALF THE TIME. Now here's the question. Who among your neighbors--all who say we can't afford immigrants or health care or green energy--then bother to ask 'can we afford it for these weapons?

My guess is practically none do.

The interesting question is why. First, they think we need them to be safe. We don't. They don't even work half the time. Second, they think we need them to sell them to the Arabs oil guys to protect the oil. We don't. All it means is some people get rich on the sales, and it's not us.

The third is the one not mentioned much. Making weapons is a jobs program. About 10% of the workers in our country work for the military industries in one way or another. It pays well. It puts you in the ‘middle class’ so far as consumption is concerned.

It also pays well to the Congresscritters who get the military factories and facilities in their districts. It's a kind of affirmative action for skilled workers in the trades that build these things and supply the parts and maintenance.

Their income is on the government tab, sucking on that teat far more than all the assistance cases for those at the bottom combined.

If you think the F-35 protects you, read this NYT article above. It doesn't, and in a way, it doesn't matter. It does a 'more important' job. It's a drug that dopes up a large number of workers and their families. It clouds their brains so they are blind to what the country really needs, and why we live in a culture of death, guns, and slaughter, and think it's normal.

It isn't normal. Awaken, and take a stand to end it. Find your local peace group. We have Beaver County Peace Links, and we have a table at the Big Knob Fair. Come visit us.

0 notes

Photo

IT WILL TAKE MORE THAN TODAY'S HEARINGS TO IMPEACH TRUMP

By Carl Davidson

Keep On Keepin’ On

That’s my conclusion from watching today’s Mueller hearing and the ensuing commentary. I'm one who believes that when it comes to high crimes and misdemeanors, Trump is guilty as sin. But that's because I've not only read 'The Report', I've dug into a lot more, beyond the parameters put of the Special Prosecutor and his team have been allowed to do. Trump, for example, has been laundering billons for Russian oligarchs for decades, ever since his Atlantic City casinos went bust. But these kinds of facts, along with Trump’s tax returns, are supposed to be out of bounds.