catsarticles

2 posts

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Why I’m doing something about plastic - and you should too

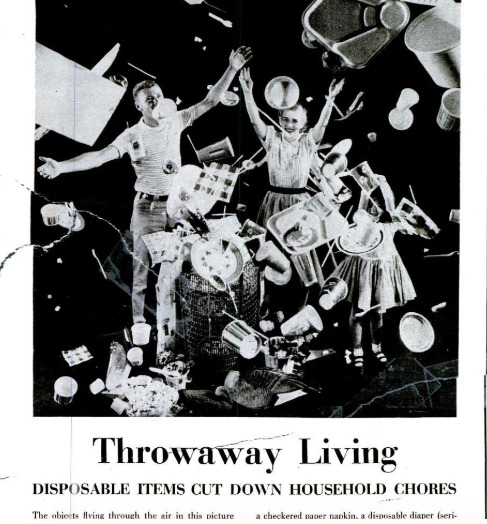

Plastic is a big problem for the environment. It pollutes our water systems, kills animals, disrupts ecosystems, and leads to public health disasters due to waste mismanagement in countries to which landfill is shipped for processing. Plastic breaks into smaller and smaller pieces (‘microplastics’) and then enters our body through the food system, with little understood effects on our bodies. Petrochemicals derived from fossil fuel production are used to make almost all plastics, the same fuels driving dangerous climate change. Plastic is also an accelerating problem. In the past decade humans have produced more disposable plastic than in the entire 20th century.

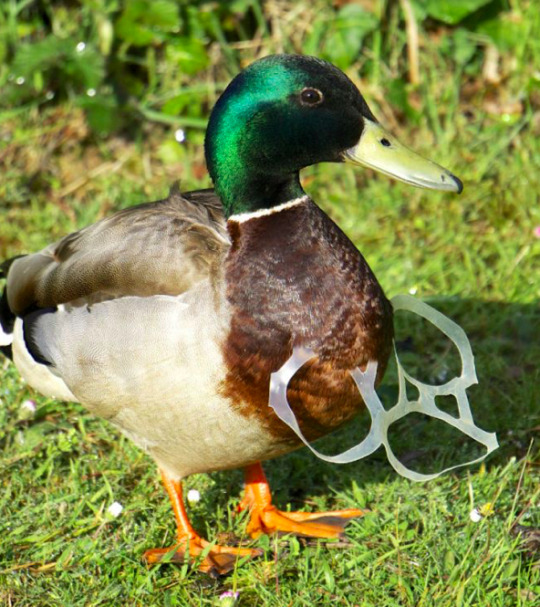

We have all seen the images, birds feeding their chicks plastics, trash in a dead whale’s stomach, or the excruciating video of a biologist trying to extract a plastic straw from a sea turtle’s nose. An intact plastic bag was found at the bottom of Mariana Trench (Source). Microplastics that have shed from our clothes (nylon and polyester shed in the wash) have been found in the snow in Antarctica (Source). A recent study has highlighted the microplastic contamination in the River Thames, estimating that 94,000 microplastics per second flow down the river in places (Source). Modelling has predicted that there will be more plastics than fish in the ocean by weight by 2050 (Source). The impact on humans is perhaps less well understood. Plastic enters the food chain via trophic interactions (animals feeding on one another) or into drinking water through wastewater effluent. The WHO has found microplastics to be frequently present in fresh and drinking water (Source). Poor waste management, including of importation of the ‘world’s landfill’ leads to mountains of waste blocking rivers and polluting cities in countries such as Indonesia, Thailand and China. The effects of plastic waste mismanagement have been linked to respiratory distress, cancer, hormone disruption, and food chain contamination with high levels of hazardous chemicals has been demonstrated in local produce in Indonesia (Source). Single use plastic is therefore a life and death problem for animals and humans alike.

Plastic is a polluter. In 2019 alone, the production and incineration of plastic was forecast to add more than 850 million tons of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, equal to the emissions from 189 five-hundred megawatt coal power plants. As plastic decomposes in landfill it releases CO2, as does burning plastics in incinerators (including a number of other toxins released into the air). If the production, disposal and incineration of plastic continue on their present growth trajectory, by 2050, the global emissions from plastic could emit 2.8 gigatons of CO2 per year, releasing as much emissions as 615 five-hundred-megawatt coal plants. If growth in plastic production and incineration continue as predicted, cumulative greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 will be over 56 gigatons CO2e, or between 10-13 percent of the total remaining carbon budget (Source).

Of course, plastic will continue to play a vital role in healthcare, industry and production of essential every day consumer products. But we can, and we must, phase out the throwaway stuff. We can do this as individuals by exercising our powers as “conscious consumers” through our buying and our influencing powers.

Reduce, re-use … recycle?

There is no doubt about it, it is preferable to recycle materials that can be over other means of waste disposal. But it’s not a complete solution. Although estimates of how much plastic waste is recycled vary, a 2015 study estimated that of all of the plastic waste ever generated, approximately 9% has been recycled, 12% has been incinerated, and 79% has accumulated in landfills or the natural environment (Source). In addition, not all recycling is considered equal. ‘Upcycling’ is when something is recycled into another product of equal or greater value than the original product. Most plastic recycling is ‘downcycling’ as the recycled plastic products are of lower value than the original product and can only be used in limited applications (for example, plastic ‘timber’). Because of this degrading effect, plastic may only be recycled once before ending up in the environment. Not only that, but when shipped to other countries, such as Indonesia, recycling can end up being sorted by hand, mostly by marginalised communities who face incredibly poor working conditions and pay (see more).

Plastic is extremely durable, hence its popularity. But this means that, in terms of waste management, this is a material that is not meant to be managed. Our actions as consumers must certainly start, but shouldn’t finish, with recycling. Ultimately it is better to reduce overall use of disposable plastic products in the first place.

The pervasiveness of plastic

To understand the pervasiveness of plastic, make a list of products around the house that contain plastic that you use on a daily basis. I tried to do this and gave up at breakfast (teabags release microparticles of plastics into tea). Of course there will always be certain levels of plastic in the world. It’s cheap, durable, and essential for some (e.g. medical) products. But it is undeniable that we are surrounded by ubiquitous, and more often than not superfluous, plastic packaging. We are also throwaway consumers, who place no value on reusing and repairing common household items, due to their low cost and replaceability. Research from DEFRA found that waste from households in England amounted to 22.8 million tonnes in 2016. This is equivalent to 1.1kg per person, per day (Source).

Why me?

The impacts of my individual action are surely a drop (or a microplastic particle) in the ocean of plastic waste? Plastic free alternatives are usually more expensive, and almost always less convenient. The places that are available to me as a consumer don’t align with my plastic free consumer desires, but what choice do I have? I put this dilemma to Will McCallum, ‘Head of Oceans’ at Greenpeace at a recent Zoom lecture I attended. He told me that although, yes, I was a drop in the ocean, my individual actions were still worth it. The piece of plastic in my hand could end in a sea creature’s stomach. In addition, I have a voice and consumer power to amplify these issues. He suggested making a ‘crime file’ of the worst offenders, and taking to social media to pressure companies. This has been proven to work: previous Greenpeace ‘worst offender’ Sainsbury’s pledged to cut their plastic usage by 50% by 2025 following coordinated campaigning. By joining forces with other people and campaigning together, I as an individual actually can make a difference.

The rest of this article focuses on the ways we can try to make a difference as a “conscious consumer.”

A caveat

When advocating individual action it’s important to remember why single-use plastic is popular in the first place. It’s convenient. It’s cheap. Its durability keeps food fresh and sterile. Alternatives can be expensive, and often have to be purchased from specialist stores often with additional transport or delivery charges. In supermarkets the consumer is actually penalised for helping the environment by higher prices for loose and plastic free produce (Source). No one should denigrate the parent who chooses to put their children in disposable nappies, or suggest that the only way to eat is from whole foods bought plastic free in bulk when nutrition, cost, and, yes, convenience necessitates otherwise.

A passage from a book I recently read, Natural by Dr Alan Levinovitz, set out the moral trap into which the conscious consumer should avoid falling:

“This is ‘consecrated consumption’ into which the ritual of shopping becomes a kind of spiritualised retail therapy dedicated to nature… At Whole Foods, every purchase, even if it’s unnecessary, is nevertheless a good one.

To the contrary: high socioeconomic status makes one’s ecological footprint far greater – larger homes to air-condition, longer flights for vacations – and the effects of being “green” are minimal. Rich people emit more carbon even when they recycle and buy canvas tote bags full of organic veggies. The truth is obscured when rich people are the ones with time and resources to spend on living naturally. “People think environmentalists are the ones driving electric vehicles, but forget about the twenty people riding the bus” remarked California’s attorney general Xavier Becerra in 2018.”

Some recommendations

With that caveat that we must take a rounded view of our personal environmental impact, some plastic free swaps are truly easy, and enjoyable There are other benefits to shopping at smaller, environmentally conscious companies too. Ethical concerns often pervade the whole product cycle of such businesses, beyond packaging and extend to ethical sourcing of ingredients and not testing on animals. Often buying these products directly supports local, independent businesses and livelihoods.

The following are some examples of products that I have switched to over the last 12 months, all of which I would recommend:

Let’s start with the basics. A Keep Cup (I like the brand Frank Green), and a reusable water bottle. I use glass Tupperware to store my food, and carr(ied) a spork for takeaway lunches to avoid single use cutlery.

Halo coffee pods. I’m obsessed with coffee, but Nespresso pods have been described as an “environmental disaster” due to production intensive raw materials in each pod and low levels of recycling. Halo capsules (Nespresso compatible) are made from waste sugar cane, a by-product of the sugar cane industry, and can degrade in as little as 28 days in a home compost. Even more impressible, all of the packaging associated with Halo capsules is also home composable and break down into organic components. They’re also delicious – I recommend the Ristretto blend.

Splosh household products. Splosh products are delivered as concentrates in pouches meant to refill bottles you can order from Splosh, or use your own. Splosh claim that the combined effect of concentration and using pouches reduces plastic by over 90%, and the extra 10% to hit the zero waste mark is achieved by Splosh receiving your empty refill pouches back to be reprocessed. As for my review: they smell good, they work well, and the products are very good value.

Who Gives A Crap toilet paper. This company sells 3-ply 100% recycled toilet paper. Best of all, they donate 50% of profits to charity partners who build toilets and provide proper sanitation to local communities. The TP is great quality, and great value when bought in bulk.

Shampoo and conditioner bars, from Lush or Ethique. Ethique claim that they have saved around 6.5 million of typical 350ml shampoo bottles from entering landfill so far. My paper Ethique packaging told me that I alone had saved 3 of these plastic bottles by switching to a shampoo bar. They last ages, and work beautifully on my hair. I keep them in a soap dish in the shower, and believe that this is one of the easiest swaps that you can make.

Soap. When did we all stop using soap and use ridiculous tiny plastic bottles of brightly coloured gel to clean ourselves? Ditch this unnecessary plastic, do as your mum told you, and clean yourself with soap and water.

Reusable makeup wipes. Makeup wipes are notorious for clogging up sewers. There are many options of reusable makeup wipes to choose from, the best being those which require only water to effectively cleanse your face. I just wash them along with my regular laundry.

Beeswax sandwich wrappers. Use as a direct replacement for single use cling film and tin foil. They are reusable, and made from all-natural materials that are eventually biodegradable.

Bin bags. This one’s a little more equivocal. There’s evidence that biodegradable and compostable material does no better in landfill than incompostable plastic (Source). However, my chosen bin bags are made from renewable and sustainable raw plant materials instead of petroleum, meaning they have a lower carbon footprint overall than alternatives, and are non-toxic meaning they won’t leach chemicals into soil or water systems.

Fruit and veg. I always try to avoid the items packaged in plastic. By using reusable produce bags you can easily buy less obvious loose items like tomatoes and soft fruit.

Bulk buying. Although I haven’t yet made the switch to zero waste stores, I try to buy in larger quantities e.g. buying the largest container of pasta (or biscuits) on offer, meaning that less packaging is used for the same amount of product.

The following are plastic free changes I hope to introduce into my household in the next 12 months:

Zero waste stores. Stocking more than lentils and brown rice, these stores now contain a plethora of fresh and dried produce priced by weight. Waitrose is currently carrying out a trial to introduce zero waste shopping into larger stores, hopefully indicating this type of shopping may become more accessible in the future.

Sanitary products. As a person who menstruates, I’m aware of the pervasiveness of plastic in disposal menstrual products, and was horrified to hear that conventional tampons and pads are the fifth most common item found on Europe’s beaches. There are an ever increasing number of alternatives to the products that I grew up with available to consumers now.

Toothpaste tablets. A totally plastic free alternative to replace non-recyclable toothpaste tubes.

DIY deodorant. Sustainable, plastic free, and added confident that you aren’t applying anything unknown to your skin.

Clothing. Some companies, such as Patagonia, are industry leaders in creating clothes from recycled material. Nevertheless, items such as polyester fleeces still shed microplastics into the water supply upon washing, making this problem seem intractable. Nevertheless, by ditching fast fashion and buying second-hand rather than new, I’m still breaking the consumption/waste cycle and getting more use out of durable plastics in clothing.

Using consumer power to change the industry

In research conducted before the pandemic, PwC’s Global Consumer Insights Survey 2020 showed that customers had become more interested in caring for the planet, and recommended that companies will need to innovate to meet the expectations and retain the loyalty of these customers. Forty three percent of the global respondents expressed that they expected businesses to be accountable for their environmental impact.

In my view, it is preferable that, rather than putting all of the onus on the consumer to make difficult choices finding more obscure items, retailers should take the responsibility (thereby putting pressure on the manufacturers and further up the supply chain).

I’ve mentioned the changes made by Sainsbury’s as a result of Greenpeace campaigning, but there are a number of other instances of major companies making changes in the UK following consumer pressure. In terms of UK supermarkets, (amongst others) Morrisons has committed to make all of its own brand plastic packaging recyclable, reusable or compostable, and to reduce own brand primary plastic by 50%. Lidl have removed all black plastic (which can’t be recycled) from fruit and veg packaging. Asda’s fashion counterpart Asda George has committed to selling products made from recycled plastic bottles and clothing, as part of the chain’s commitment to using polyester sourced from recycled materials by 2025

Lifestyle brands are realising that the long term future of a brand relies on its corporate image being sustainable, as a new generation of consumers cite environmental concerns as a priority. In 2018 Proctor & Gamble released sustainability goals called ‘Ambition 2030’ and state that they are “working to make social and environmental responsibility an integral component of every brand in our portfolio.” The group aim for100% of recyclable or reusable packaging, and “a meaningful increase” in responsibly-sourced bio-based, recycled, or more resource efficient materials. Unilever celebrates operating with 100% renewable grid electricity in its manufacturing operations worldwide, and zero waste to landfill across all of its factories. The group aim to make plastic packaging reusable, recyclable or compostable by 2025 and to use at least 25% recycled plastic in packaging by then. The United Nations awarded the company’s CEO its Champion of the Earth Award in 2015 for “demonstrating the need for long-term corporate thinking that accounts for social and environmental concerns.” Unilever’s chief research and development officer, Richard Slater, highlighted companies’ lead role in mainstreaming sustainability when he said in an interview on NPR, “The onus is on us as consumer companies to innovate and come up with solutions that are great for people…[and]…convenient at the right price.”

Although positive steps are being taken, there is still so far to go in terms of companies taking responsibility for the lifecycle of their products. Consumers must be critical and demand real action, and not settle for companies making (intentionally or unintentionally) false claims regarding the environmental friendliness of their products, a process known as “greenwashing.” Organisations renowned for their environmental purpose-driven marketing are still huge contributors to the sustainability crisis. Procter & Gamble, Unilever, Mondelēz, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo were cited among the top-10 corporate contributors to global plastic pollution in a study conducted by Greenpeace and the Break Free From Plastic Movement last year (Source). A report published by the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives named Nestle and Unilever as the top polluters based on a series of brand and waste audits conducted in six cities in the Philippines, mainly due to their production of single-use sachets (small packets containing single-use quantities of any material) that are marketed in the global South but not other parts of the world (Source). It’s not good enough for companies to sell products in packaging that might meet stringent EU standards, but then absolve responsibility in countries with historically lesser environmental protection. Decisions made in the boardrooms of companies in the global West must take real account and responsibility for the globally shared problem of plastic production and waste management. Therefore, the scale of the problems caused by these huge manufacturers, retailers and brand groups shouldn’t be underestimated, but nor therefore should the possible impact were these companies to take meaningful steps.

How to use consumer power to influence companies to change their ways (without spending anything)

Tell the brands and businesses you support that it’s time to change the way they use plastic:

Sign petitions and get behind existing campaign. Greenpeace’s petition (currently with over 2 million signatures) aims to put pressure on supermarkets to ditch throwaway plastic packaging. Oxfam’s Behind the Brands campaign helps consumers understand the environmental impact of a number of household brands, and encourages consumers to reach out to these businesses directly to engage with the issues. I also love this story about a group of primary school children who took their message to Universal Pictures via a petition to ensure that the release of 2012’s ‘The Lorax’ provided a platform to provide information to children on the environmental message of the movie.

Create social media storms and use hashtags, such as #PlasticFreeFriday or #PointlessPlastic, which are an easy way to attract the attention of corporates and fellow consumers alike. Tag brands in photos of offending items to ‘name and shame’ the throwaway mentality these products cater to, and to encourage companies to adopt ‘extended producer responsibility,’ a strategy to make the manufacturer of a product responsible for the entire life-cycle of the product.

Engage in local (friendly, non-confrontational) protests like the Mass Unwrap campaign to raise awareness in supermarkets that their customers dislike superfluous packaging.

Wherever possible, visit, support (or create!) local art installations, such as the ‘Plastic Soupermarket’display containing local littler found on the banks of Amsterdam’s waterways.

In addition, community-led actions like Plastic Free Caerphilly linked local businesses and concerned residents motivated to tackle single-use plastic, and resulted in the town being awarded “plastic free community” status in July 2019.

The role of Governments

PwC’s Global Consumer Insights Survey 2020 found that responders answered that the government bore the most responsibility for creating a sustainable world. Cynically, companies aren’t going to voluntarily do the right thing. There are a number of environmental pressure groups advocating for a number of top-down measures that leave companies (and consumers) with no choice to comply. Previous (successful) campaigns have resulted in a ban on microbeads (Source) and plastics like straws and stirrers (Source), in line with the EU standards and targets included in the Single Use Plastics Directive. Bangladesh was one of the first countries to ban the use of plastic and polythene bags in 2002, and since October 2015 the UK Government made it compulsory for large shops in England to charge 5p for all single-use plastic carrier bags (Source).

Governments are driven by a number of competing pressures, but there is almost no doubt that the global, accelerating clamour for sustainable practices to be embedded within society and for Governments to use their power to bring about this change, has led to policies, proposals and plans advancing sustainability.

Find and sign petitions. Petitions on Parliament UK that reach 10,000 signatures will get a response from the UK Government, and those that reach 100,000 signatures will almost always be debated in Parliament.

Lend your support to established campaigns. Friends of the Earth’s ‘Help reduce plastic in oceans’campaign to commit governments to introduce a plan to phase out and better manage plastics. WWF’s campaign aims to create a global and legally binding UN agreement to set strict goals for plastic pollution reduction in each UN member state and instruct each state to create national action plans to meet these goals. Coalition groups like Zero Waste Europe influence European policy makers and Member State governments on a number of issues, including directly petitioning the European Parliament to be at the vanguard of tackling plastic pollution and single use plastics, and highlighting the injustices of the global waste trade and calling for Europe’s waste to stay in Europe.

Write to your MP on local issues or in support of relevant legislation in Parliament, and apply pressure to your local authority to improve its recycling offer. Although US focused, Greenpeace’s lobbying toolkithas some useful resources for engaging with elected officials.

And of course, vote for candidates with a proactive stance on addressing green issues.

In conclusion

Make an individual action plan. Start with a 1 month plan, then 3 months, then 6 months. Start small, and work up to larger goals and see the process as a journey with no clear destination or stops along the way.

Start with recycling everything that you can (and stop buying the things you can’t). Give up throwaway plastic bottles and plastic cutlery. Start to seek alternatives to small sachets and packaged single portion items. Then, start being organised with your shopping. Research new places to shop and form new habits. Buy quality and long-lasting household items and clothes over cheaper items that will need to be replaced. Make your feelings known through making a Twitter account and calling brands out. Engage in some community campaigning, and make your collective voice heard by manufacturers and lawmakers.

Be kind to yourself as a consumer making often difficult choices. Convenience is essential in many of our lives, and safety concerns and medical need are at the forefront of our minds and in our choices. But, please, don’t do nothing because you can’t do it all.

Further reading:

Cat’s twitter account: https://twitter.com/WhySoWasteful

See more information and tips at https://www.plasticfreejuly.org/.

The Story of Plastic documentary: https://www.storyofplastic.org/.

BBC David Attenborough documentary Blue Planet II: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p04tjbtx.

0 notes

Text

The £15 delivery that can save the planet, and your dinner?

‘Veg box’ schemes (but in fact these boxes can also contain fruit, eggs, dairy produce, meat and cupboard staples) are a way of getting (mainly) local, seasonal, and sometimes organic, farm produce delivered to your home.

Courgette and vegan ricotta pasta, with homemade lettuce pesto, and roasted tomatoes on sourdough

Why choose a veg box?

Veg box schemes have developed to meet some of the environmental challenges that exist within the food chain, from farm, through our supermarkets, to our plates, and then too often into our bins.

The value of edible food wasted in the UK is around £19 billion (Waste and Resources Action Programme (“WRAP”) (2020) report). Reducing food waste is an effective solution to fighting climate change, as recognised by the inclusion in the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals of Goal 12 – halving per capita global food waste. This proposed 50% reduction would lead to a reduction of the carbon footprint by 1.4 GtCO2 equivalent per year (UN FAO (2015) report). For context, that is over four times the annual CO2 footprint of the UK (source: Global Carbon Project).

All food products generate their own carbon footprint through emissions related to transportation from farm to plate. The worst offender is air-freighted food, which tends to be used for highly perishable foods including fruit and vegetables. Around 0.16% of food miles are estimated to be by air-freight (Poore & Nemecek (2018) report). For most food products transport contributes to up to 10% of that product’s carbon footprint (Poore & Nemecek (2018) report). Defra statistics (March 2020) show 53% of food consumed in the UK originates in the UK, and Farmdrop’s website estimates that just 23% of fresh fruit and veg sold throughout the UK is grown here.

Supermarkets overuse single use plastic and packaging, often on fruit and veg that comes already packaged nicely in its natural skin. Customers are incentivised to buy these items - the team behind the 2019 BBC series ‘War on Plastic’ found that there was a price difference of 42% between the same items packaged and without packaging in Tesco, with the loose goods costing significantly more. The team found that residents in one single street in Bristol collectively had 7,145 pieces of plastic in their kitchen. Helped by programmes such as the BBC’s Blue Planet II, we are recognising the many different types of tragedy caused by industrial pollution and the discarding of plastic waste, as well as recognising the resource intensive production and disposal of plastic.

In addition to quantifiable environmental impacts, it’s a truism that fresh, seasonal food is tastier. And veg boxes have faced an unexpected challenge and opportunity in being able to provide food to millions of households who are forced to seek produce in different ways to usual due to the coronavirus pandemic. A YouGov study undertaken between 7-9 April 2020 found that 3 million people have tried a veg box scheme or are buying direct-from-farm for the very first time, as a result of the pandemic.

Garlicky, lemony spring greens stir fry

The larger players

There are a number of websites offering differing versions of the veg box concept. I considered in brief some of the larger players: Oddbox, Eversfield Organic, Riverford, Boxxfresh, Farmdrop and Abel & Cole. The companies distinguish themselves in different ways. Oddbox claims to be the only company that rescues fruit and vegetables, and their business model is to deliver misshapen and surplus produce. This is to directly counter the problem that supply chain food waste makes up 30% of the total UK food waste (WRAP (2020) report) The majority of other companies offered meat, dairy products, eggs, bread, and cupboard staples alongside a veg box, or had the option to purchase items separately (i.e. not as a veg box bundle). These companies buy from mainly local suppliers and farm partners, with Farmdrop working with more than 450 producers. Companies like Riverford plan box contents and order in advance from their suppliers, aiming to grow only the amount they expect to need. Eversfield Organic and Riverford offered almost exclusively organic certified products (for brevity, and because it was not a feature of all of the veg boxes, I haven’t written about the benefits of organic produce to biodiversity, nutrition, and emissions).

None of the companies offered exclusively British grown produce. Oddbox state that you could receive bananas, avocados and mangos in your box, however this is produce that has already been, or would be, rejected as ‘imperfect’ as part of an imported crop. Riverford state that 80% of their veg is UK grown across the year, and they never air-freight (Farmdrop and Abel & Cole also make this commitment). To maintain quantity and variety of produce, Abel and Cole do not claim to rely solely on British or local suppliers, but aim for transparency, and do offer an All British veg box.

All the schemes pledge to reduce, and continue working on reducing, packaging, and make any packaging recyclable or degradable. Riverford currently estimates that its veg boxes contain 82% less plastic than the equivalent packaged products from major UK supermarkets.

Apple crumble

My review of Oddbox

My small fruit and veg box came with a brochure telling me the origins and reason for inclusion in the box of my produce this week. I received: a box of red grapes (from South Africa, imperfect colours), 4x apricots (Spain, surplus), 4x apples (UK, surplus), a box of cherry tomatoes (Spain, surplus), 2x courgettes (Spain, too small), 5x potatoes (UK, surplus), 9x white onions (UK, too small), a head of spring greens (UK, surplus), a head of green ‘living lettuce’ (UK, surplus), and a bag of salad leaves (UK, surplus). Overall I was slightly surprised that not all of the produce originated from the UK, however Oddbox explains that these products would have otherwise gone to waste and have not been imported for the purposes of the box. Some of the items deemed imperfect for sale were a little more ‘wonky’ than equivalent products that I could have picked up in supermarkets, but none of the items would be unsaleable, in my view.

This week’s small fruit and veg Oddbox

The brochure explained that the inclusion of two leafy salad items was due to the British leafy salad season just beginning, and the sudden crash of food service items they were destined for. This made a lot of sense to me, although quite how I was going to eat all of that lettuce made less so.

The quality was without exception fantastic. Apart from the courgettes and tomatoes, I would have been unlikely to choose any of these items in the supermarket, however I decided to get creative and avowed to not waste a thing. I hoovered up the grapes as a snack, and then supplemented the box with a couple of vegetables that I already had in, herbs from my windowsill, and a well-stock store cupboard, and came up with the meals included in the photos in this article. I also made a huge potato curry with onion bhajis, which, despite my best efforts, I couldn’t make presentable.

In order to avoid generating any food waste, I froze most of my spring greens. You can freeze most vegetables, and I recommend lightly cooking them first. Pestos are also fantastic ways of using vegetables, and I made a pesto from the abundance of lettuce we received, which we then used on bread, pasta, and as a salad dressing. I didn’t this week, but another great way to use leftover or awkward vegetables would be to cook them into a frittata, or savoury crepe (chickpea/gram flour can be use to make both as an alternative to using eggs and milk).

The tomatoes, grapes, salad leaves and lettuce were packaged in plastic. In my opinion only the salad leaves needed any kind of additional packaging, so the packaging was a little wasteful. The produce is not organic, which is a shame, but overall I liked the fact that this produce might have gone to waste otherwise, and was impressed with the selection and the quality for the price paid.

Simply dressed salad with homemade courgette fritters, and sweet chilli sauce

Critical thinking

Although food wastage from farm to plate should of course be discouraged, household food waste makes up 70% of the UK’s total food waste (WRAP (2020) report). Oddbox estimate that households waste 25% of their weekly shop, on average, which amounts to over 10 million tonnes per year (Friends of the Earth, 2020). Veg boxes on the most hand are not like markets where you can choose what you’re getting, you just get a selection of local food that is in season. For fussy eaters, or consumers strapped of time or kitchen skills, it could be a challenge to fully use all the produce that comes in a veg box, particularly when the vegetable may be more unfamiliar or difficult to incorporate into a modern diet. Although some companies have tried to mitigate the wastage of their products (Oddbox allow three exclusions per delivery, and Abel & Cole and Boxxfresh are fully customisable), tailoring boxes is in some ways anathema to the purpose of the boxes, which is to provide consumers with fresh, local, seasonal and available food. I found myself eating very differently than I would usually, and creating dishes to use up the ingredients that I wouldn’t have usually made (lettuce pesto and courgette fritters, for example). This was an interesting challenge for me, but in the current times I have more time to plan my weekly menu upon seeing the boxes content, and spend more time in the kitchen than usual. Given that a huge amount of the problems associated with food waste are in the journey from fridge to bin, veg boxes aren’t a complete solution to food wastage, and instead we must collectively improve our food skills, including meal planning, storage, and creative use of leftovers.

The cost of the boxes may also be a deterrent. The medium sized Oddbox (7-8 varieties of veg and 4 types of fruit) costs £14.99, and Farmdrop’s equivalent costs £12.75. The organic box from Able & Cole contains 7 portions of veg and 2 portions of fruit costs £19.95, and the medium offering from Eversfields Organic and Riverford (8 varieties of organic vegetables) costs £15.25 and £15.35 respectively. Compared with supermarket shopping, the items will generally be more expensive per item, however if you did a direct comparison with fully organic produce in a greengrocers the price would be equivalent, or less. Anecdotally, however, users of these boxes think they have saved money, as the boxes mean that more meals will be plant-based and encourage cooking from scratch (both of which are cheaper ways of eating). Additionally, there is a premium to be paid for a vastly superior taste, as one colleague said: “potatoes and tomatoes which actually have flavour!” Of course everyone will make individual choices based on their budgets, and whether such choices ultimately represent value.

Salad with roasted butter beans, tomatoes, and a coriander and jalapeño ‘mole’ dressing

In terms of corporate responsibility, I saw some criticism of companies like Abel & Cole, who inevitably have overheads and shareholders to pay. Abel & Cole however are a certified B-Corp and as a part of this have made a large amount of their company information public. In general, the ethos I saw from these companies is what you expect of companies operating in the market for environmentally conscious consumers: they recognised that every element of their business always had room for improvement (be that choosing and paying local producers, packaging, deliveries, farming standards), and that a truly sustainable business had to be positive in each of these areas. All the companies seems to be trying to improve on the 9p received by producers for every £1 spent in a supermarket (People Need Nature (2019) report), and veg boxes are a way for smallholder farmers to supply more directly to the public.

I wondered about delivery emissions of veg boxes from supplier to doorstep. It appears unequivocal that delivery services are no worse for the planet than independent shopping trips, assuming that the majority of households do their shopping in a car. Exeter University found that because home delivery consolidates many people’s shopping journeys into one, it is generally more efficient than going shopping in your own car (Coley, 2009). Abel & Cole adapt their daily delivery routes to minimise fuel consumption, and Oddbox deliver overnight to take advantage of quieter roads. In addition, the commitments to avoid air-freight address the largest source of delivery emissions. However, the position is more nuanced in terms of growing tasty, out-of-season produce that customers demand at home in the UK. A 2009 paper compared the environmental impacts of importing Spanish field-grown lettuce into the UK during winter with lettuce produced in the UK in heated greenhouses, and found that importation from Spain produced fewer GHG emissions (Hospido et al, 2009). A similar picture holds true for crops like tomatoes grown in warmer European climes, compared with greenhouse grown in the UK. Anyone who eats seasonally will understand the challenge of maintaining a variety of produce acceptable to the usual consumer in the UK at certain times of year, and given that a large draw of these veg boxes are the quality of the produce, some element of food importation seems inevitable.

It’s less about where our food comes from (although there are of course a number of reasons apart from purely environmental ones that may influence why you choose UK suppliers), than what we are eating. Data from the US shows that substituting less than one day per week’s worth of calories from beef and dairy products to chicken, fish, eggs or a plant-based diet reduces GHG emissions more than buying all of your food from local sources (Weber & Mattews, 2008). There are massive differences in the GHG emissions of producing a kilogram of different foods, with plants consistently being the lowest (lamb and cheese – 20kg CO2 eq, beef - 60kg CO2 eq, peas – 1kg CO2 eq, source: Our World in Data). Producing livestock for human consumption contributes 14.5% of annual GHG emissions (Friends of the Earth, 2020), and is resource heavy - more food is obtained from a given area of land if we consume plants directly rather than pass them through an animal first. 40% of arable crops are fed to animals (source: Food Climate Research Network, 2020). The IPCC estimate that by 2050 a global switch to a plant-based diet would reduce global CO2 emissions by up to 8 billion tonnes per year, relative to business as usual (IPCC, 2019). The meat and dairy options in the boxes offered by most of the companies considered may at least have the effect of encouraging consumers to think more about where their animal products are coming from, and to re-think the narrative that these are essential products, especially eaten in the quantities eaten in the UK today.

Vegan apricot cake and cream

Ultimately we have power as consumers, and every pound spent is a conscious choice. I encourage you to examine your own shopping habits, and whether you could shop more seasonally, locally, organically, and plastic-free. Although it is certainly not the only option, it may be that the easiest way to do this is to take up a subscription to a veg box, and find one that works for you, your tastes, and your time available. Reconnecting with the food on our plate and its journey to get there makes us all more conscious consumers, and can bring great enjoyment, both in times of pandemic and beyond.

Catherine Lucas

2 notes

·

View notes