Text

Fin

Art in Paris: A Lineage of Light

I woke up the night before my flight to Paris in tears. Traveling is not my forte, nor is leaving my loved ones—and while grateful for the opportunity, I had not yet recovered from the stress the semester brought. The thought of visiting such a dense city with an endless list of attractions to see overwhelmed my logistic calendar and initiated overflow in my artistic mind. Yet three weeks later, I have found my own sense of love and purpose in the history of the artists that came before me, through a series of marvels and mishaps in this rich city.

That’s not to say, though, that I have processed all that I have seen—with Paris’ sheer volume in consideration, I have perhaps digested half of the material that has met my eyes. I have learned in my time here that I much prefer to be a thorough thinker, but I can’t leave the museum without seeing each and every piece. I have yet to strike a balance; obviously, I had to forego the complete itinerary in the Louvre, but generally I found myself circling every attraction several times in fear of skipping something. I’ll aim here to outline our trip by subject matter, so as to reorder my scattered brain.

We covered religion fairly heavily in the first eight days; the intersection of church and art during the baroque period ensured that our art education tour make stops at the Notre Dame, the Saint Chapelle, and the Sacre-Cœur. Even with the understanding that Catholicism facilitated commissions and supported artists, I still felt as though the shadowy realism emphasized suffering more than I would have liked. I found the Sacre-Cœur much lighter than the other two, both literally and figuratively. Its imagery directed toward hope and its windows open, this church seemed closer to the spiritual aspect of religion I had hoped to see.

I found a little more light in the Parisian gardens, which were probably my favorite part of the trip. The Jardin du Luxembourg felt unreal—I wandered parts of it by myself and found otherworldly alcoves that I never wanted to leave. Versailles was regal and grand, and the part of the castle that seemed most authentic to me. The outdoor amphitheaters indicated Louis XIV’s admiration for the arts, which among the king’s qualities was one of his best. Monet’s gardens, however, were by far my favorite experience here—a day trip to Giverny was the long-anticipated rest I had needed, and all of the artistic juices that had been brewing in the first two weeks here spilled out once I reached the lily pond. I bought an assortment of postcards from the gift shop and set myself down at the edge of the pond in Friday’s thunderstorm to write as much as I could.

This helped to establish a theme that repeats itself in my life, but is just now reaching me—even the greatest artists need a place to relax. Impressionist themes in the Musée D’Orsay encouraged this sense of serenity within me; I accepted my human weakness and pledged to allow myself the right amount of rest. My nerves subsided and my shoulders relaxed, and I was able to absorb Paris from a much more open perspective for the remainder of the trip.

Everywhere I looked, inspiration struck. Between all the sights we had seen in the city and our plans for the third week of classes, I had no shortage of information to pull from. I picked up on all the themes we had discussed in the context of power declarations through grandiose and seemingly artificial displays. Versailles’ gaudy gold and Notre Dame’s towering spires seemed unimpressive to me, in contrast to the stunning natural beauty of Monet’s gardens. And though the literal power laid in the hands of the monarchy and the deity to which they prayed, the artists held influence in their brushes. It seems that in the Paris salon culture, they knew a little of their power, and made use of it by respecting and collaborating in an intricately connected network. The caliber of this mutual respect between artists affected me strongly; always passionate about bringing together unlikely collaborators, I found myself warmed by the apparent camaraderie among artists in Paris. They retained their personal voices but convened to discuss and refine ideas—this prompted a spark and several ideas for my artist collaborative back at USC.

Paris has taught me an incomparable amount about my favorite classical and modern masters, but also shown me sides of myself that had yet to be discovered. In light and leaves and royalty and religion, I learned that balance would save my creative process and that within that process, my peers would be the ultimate consultants. The artists before me took the time to learn this themselves so that I would not have to—I am taking it upon myself to responsibly carry the knowledge I have gathered from their lifestyles and masterpieces. And with that, I say au revoir, and hope that the spirit of Parisian salon culture flows within me until I return.

CSK

0 notes

Text

Dix

This blog, like last week’s Monday blog, covers this weekend and Monday—the Picasso Museum, a picnic and sunset at Tour Eiffel, the famous catacombs, and the Centre Pompidou.

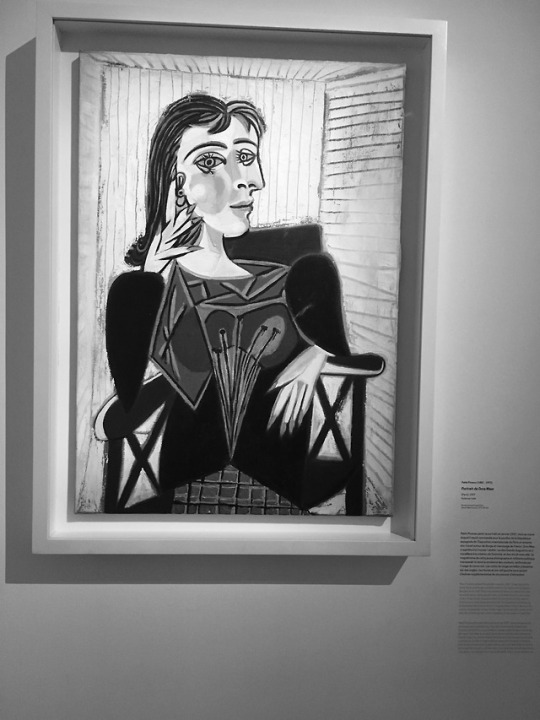

First, the Picasso Museum—Caitlin, Mark and I enjoyed all five floors (just fifteen minutes from us, walking). While two of the floors were completely dedicated to his work Guernica, the piece itself actually rests in Madrid, according to Picasso’s wishes that it be placed there once the republic was restored. The museum, however, included multiple reinterpretations of the work by several notable contemporary artists, as well as thousands of pieces for context; news articles, painting/sketching studies, portraits, and more. I appreciated the social context—I think it’s incredibly important for a piece like Guernica. I believe, however, that good art should be able to do both: hold up within context and be interesting without any at all. I think that Picasso is successful with Guernica, though the context makes it much more poignant.

Next, a picnic and sunset at Tour Eiffel, which was absolutely beautiful on its own. The lights that came on at sundown made it all the more special, and helped to really cement the feeling of being in Paris. There was a brief moment where the phantasmagoria dissolved and I actually faced the reality that I was in a foreign country.

One, as we are constantly reminded here, that has lots of history—the catacombs were eerie, but also sad—many had markings that described famous battles during the revolution, and piles of bones were stacked neatly for each, as though fighting and discarding bodies had become routine and even commoditized when the catacombs were reopened for display.

On another note, the progression of all of our art history travels continued at the Centre Pompidou today. I noted the presence of several artists I love from their Los Angeles exhibitions: Lichtenstein, Close, Warhol and Pollock from the Broad, Kandinsky from a special LACMA exhibit, Matisse from the Getty, and more. I even noted a few pieces by Senga Nengudi, whose art is on a special display in the Fisher Museum at USC. Seeing my own favorite artists tied into French culture and history, in a progression from Picasso and Chagall to Mondrian helped to complete the circle—especially between Picasso’s earlier works and studies from Saturday’s visit, which linked through cubism into Chagall’s style, until Mondrian is painting with literally lines and squares. This continuation fascinates me, and I look forward to the day when I can trace my peers into this lineage. Until then, you can find me collecting postcards in the museum gift shop.

*this weekend’s photos are taken on iPhone, to protect my beloved Canon from the forecasted hail.

0 notes

Text

Neuf

Today’s blog will be brief, because Monet’s garden speaks for itself, and I hope the pictures do, too. In fact, it only became clear to me after spending time in the gardens, but Monet knew all along that the colors in his garden spoke for themselves—he needed not focus on detail. Having always loved Monet’s paintings, I quite enjoyed the gardens and the feeling of dreaming myself into paintings I had admired since I was very young.

After surveying the lily pond, where my brother’s favorite paintings were drafted, I was inspired to run back to the gift shop and purchase postcards and a pen with which to write my thoughts, and stationed myself near the middle of the lily pond to dedicate poems to those dearest to me.

Monet’s house is covered floor to ceiling in paintings by other artists, which to me is wonderful; he shows the same sort of respect Chagall did toward his fellow artists, supporting them and appreciating their work, though some of it is very different than his.

I tried to capture a few things in my photography. Primarily, I focused on the power of nature but also wanted to convey the feeling of serenity that I felt in the garden—a few shots are out of focus on purpose, to mimic Monet’s famous style, but of course I could never do it justice. I also simply had to post these in color—it would be a disservice not to, and so I give up a little of my pride in my monochrome blog for the beauty of nature. Please enjoy!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Huit

Yesterday, we tackled the beast that is the Louvre—and as expected the Louvre won. Stepping into what is hands down the largest museum I’ve ever visited, I already knew I could not complete my usual museum agenda, which is to comb through the entire museum in one go. The count of artwork in a single wing alone would be enough to overwhelm a full day, and so we chose our battles as wisely as we could.

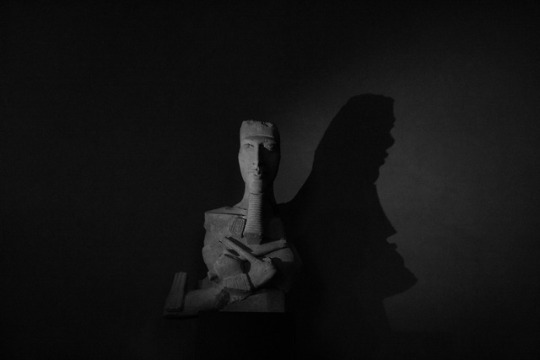

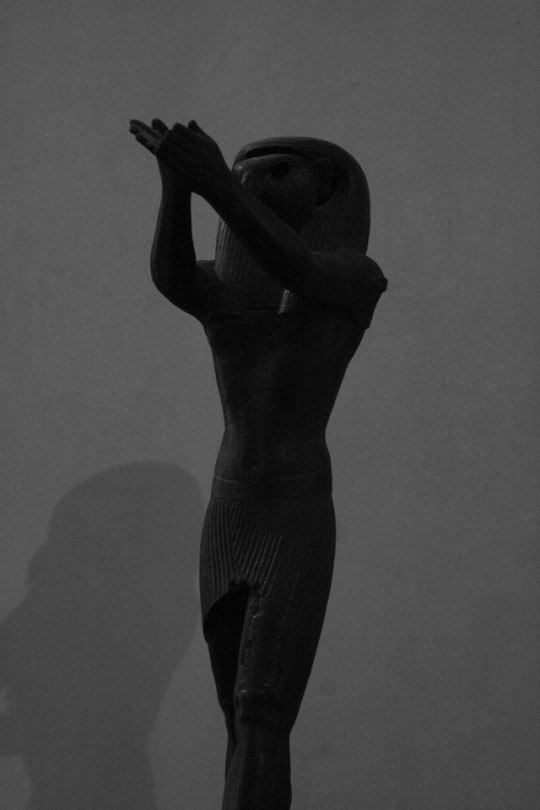

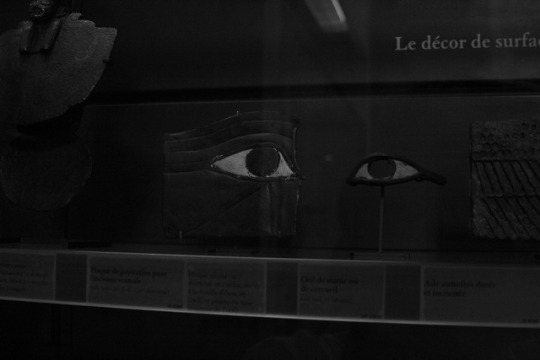

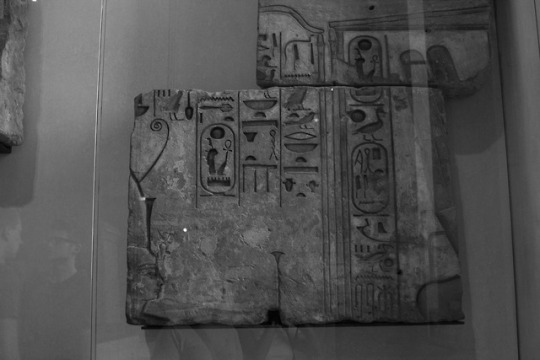

At the entrance to the department of Egyptian Antiquities, we were greeted by the Great Sphinx of Tanis (located below in an image post). Found in Egypt in 1825, the sphinx is believed to be part of the ruins of the Temple of Amun at Tanis. It features the head of a king and the body of a lion, and is marked with the names of kings Ammenemes II, Merneptah and Shoshenq I—archaeologists have noted details that could date it back to 2600 BC. Its grandeur was still intact as it stood in the museum, however; fascinated by its inscriptions, we headed further into the wing and found ourselves stuck there awhile.

The Egyptians’ respect for animals, especially cats, has always stood out to me, especially because their god of music, Bastet, takes the shape of one. I did not, however, know of their fascination with hippopotami, and noted several hippo figurines on display in the museum. Upon further research, I found that the people were afraid of hippopotami because of their power and size, but also saw them as a symbol of life from the Nile. Their habit of emerging and then submerging in the river water represented rebirth from primeval water.

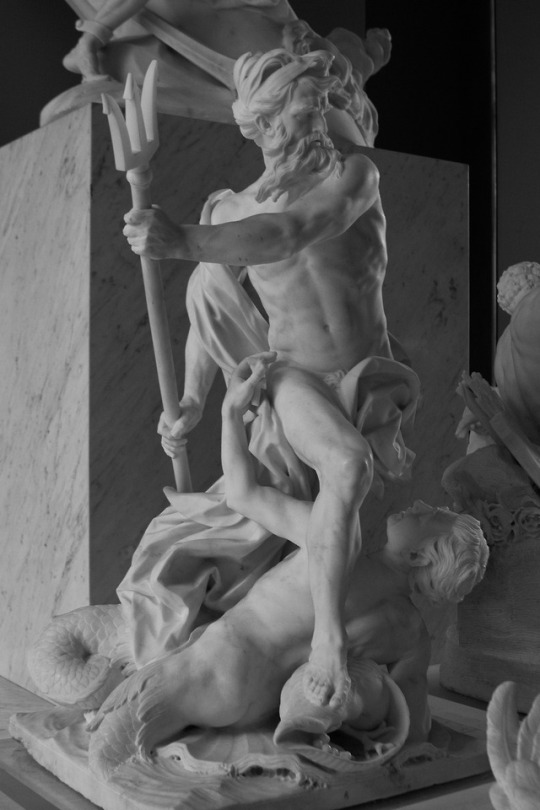

After making a point to find the Law Code of Hammurabi, we moved on to the sculpture portion of the museum, which was probably my favorite part of the day. Hallways and gardens were filled with my favorite Greek figures: Hermes, Prometheus, and more, and I reveled in their lifelike marble. The detailing on human muscles is always one of my favorite studies—it seems only fitting given my dance background.

Finally, we made a point to see the Mona Lisa—her eyes did seem to follow us across the room, but only as we were pushed by many museum-goers with selfie sticks. The painting is small, but still impressive, even if we were seeing it just to say we did.

A particular point of interest as we left the museum was that we came across no impressionism—we will visit Monet’s gardens in Giverny today to get our fix.

0 notes

Text

Sept

Yes, a Paris Opéra program with Thierée, Shechter, Pérez, and Pite is bound to be stunning. Just how stunning, however, I could never have predicted—left breathless after just the first piece, I had no idea what I was in for last night. The dancers of Paris Opéra showed all the trademarks of classicism, adapting them deftly to the athleticism of Shechter and Pite, the theatrics of Thierée, and the ethereality of Pérez.

Upon entering the Palais Garnier, audience members were instructed to wander as creatures began to roam; clad in gaudy gold and black from head to toe, the frôlons gathered and consolidated light, which rested in the chandelier-like tiara of their queen. Four dancers slunk through the palace in golden costumes that seemed almost like reptilian armadillos, adorned with small chandeliers in place of facial features. My logic knew they were people underneath, but my gut consciousness was absolutely terrified. The articulation in every dancer’s feet and back particularly created this otherworldly illusion—they were not just dancers in costumes, but beings in their own world, and we were visiting. The palace décor complimented them perfectly, immersing me completely in their world of light. A recorded score was accompanied by live violinists and singers, whose sense of urgency intensified a struggle between the frôlon queen and human men in black trenchcoats who seemed to be stealing the light. The queen’s power and Björk-like voice built into an empowering finale in which the frôlons reclaimed light and strength over the human bandits. They gathered in the theater for a stunning denouement featuring flowing cloths reminiscent of Loïe Fuller.

The next piece, a brutally honest Hofesh Shechter creation called The Art of Not Looking Back, featured an all-female cast, in grounded movement much like the style popularized in Israel by Ohad Naharin. Shechter, also Israeli, narrated and spliced a recording of his personal story while the dancers fell in and out of synchronization, their movements heavily imbued with gesture. I felt a strong juxtaposition between their physical strength and the vulnerability in the intention, which came through their demeanor and his narration. I loved the piece—it has given me an idea of the power of words in dance and the ways they can coexist, and that is something I plan on exploring throughout my senior year and in my senior thesis.

I must admit that Pérez’s piece disappointed me. While his intention was clear in studying different forms of the male dancer throughout history (Nijinsky and Louis XIV were the clearest to me), the piece seemed ill-rehearsed. Unison was wonky and improvisational partnering sections felt as though they hadn’t been given enough thought. Dancers partnered each other but not smoothly, looking unfamiliar with each other and the floor. To be fair, they are a ballet company, and this kind of work may be new to them. But in the Pite piece afterward, it was made clear that these dancers could do whatever was asked of them.

The Seasons’ Canon came alive with roughly 40 dancers onstage, each with an intricate set of counts personalized in canon and unison to reworked Vivaldi. It was stunning—Pite’s choreography manages to pull out incredible movement quality and phrasing from her dancers, and the visuals that resulted from such a large cast were impactful to say the least. I’m inspired to move now; each piece gave me a different prompt, and I am excited to research their bounds.

0 notes

Text

Six

After yesterday’s trek through the cobblestone streets of Montmartre, today’s activity was a nice break—we’ve walked over fifty miles since we first arrived in Paris, according to my phone.

We gathered on the steps of the Palais Garnier, which was built between 1860 and 1875 after architect Charles Garnier was selected from 170 applicants to design the opera house. A backstage tour of the Paris Opéra was quite the gift—not once in my lifetime have I thought that I would be able to experience such a venue from the audience, let alone from behind the curtain.

We were able to visit the gorgeous backstage warm-up room (where dancers unfortunately would greet donors that could help supplement their careers financially, among other things), which obviously had us all checking our turnout in the mirror. I was most intrigued, however, by the area directly below the stage, where sailors were hired to change sets by wheel and the phantom of the opera is said to live in the water reservoir for the fire brigade. Upon further research, I discovered that Phantom author Leroux was an opera critic and reporter before becoming a mystery writer, and his novel was heavily influenced by Poe and Conan Doyle. I understood why he would set a mystery here—the building is beautiful for scenes, but the alluring theatre folklore is enough to intrigue any writer.

Our tour then moved on to the house itself, where we spoke about the Chagall mural on the ceiling and its many scenes. I loved that Chagall (although he did include a portrait of himself) paid homage to other great artists of his day—he even included their names around the perimeter. I dream this kind of respect among artists today, that collaborators and contemporaries can appreciate each others’ craft. And on that topic, we are scheduled to see the Paris Opéra Ballet perform tomorrow in a program that includes works by Thierée, Schechter, Pérez, and Pite—I can’t wait to experience the work among my Thornton colleagues and to admire the work of such fantastic choreographers.

1 note

·

View note