i make reblog some silly maths and biology content, mainly maths. highschool maths enthusiast

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Fun fact: by just using imaginary numbers, some Evil Math, and 101 rotating vectors You Can Create a shitty approximation of a fish.

76K notes

·

View notes

Text

Every day I go to class and someone with a PHD does fucked up shit to number and I'm like "nooooo your hurting them!" This is because I'm an empath

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

the platonic solids? pfft. wake me up when mathematicians discover romantic solids

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

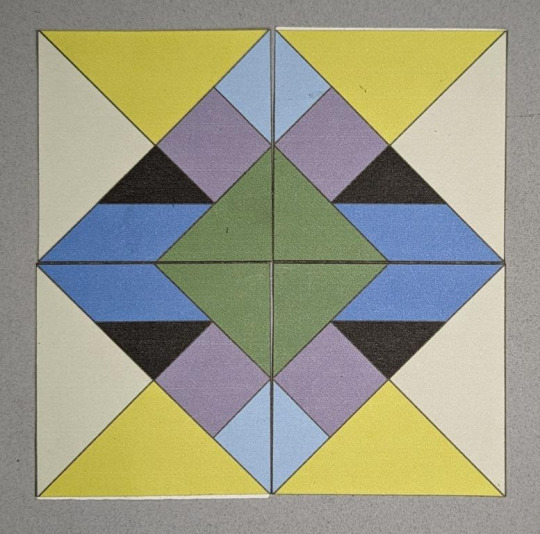

Paula's Tangrams

Paula Beardell Krieg wrote a great series on tangrams this month. Exploring the shapes, making the pieces, playing with them. But in the final she plays with the symmetry and it is lovely.

Just too delightful not to share.

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

bruh isn't this the null set symbol

It’s also used in Danish

792 notes

·

View notes

Text

based on the precedent set by sin², sin⁻¹(x) should be equal to 1/sin(x)

based on the precedent set by sin⁻¹, sin²(x) should be equal to sin(sin(x))

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

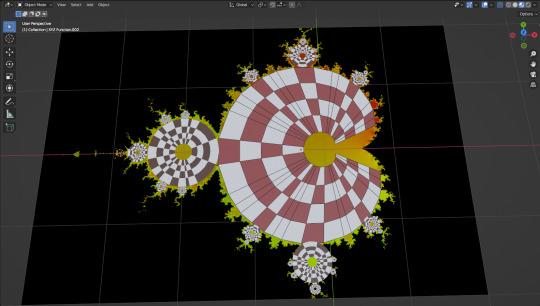

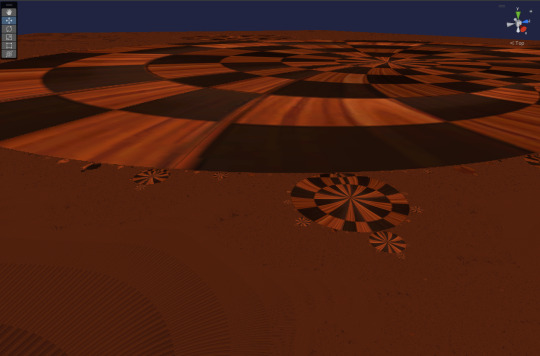

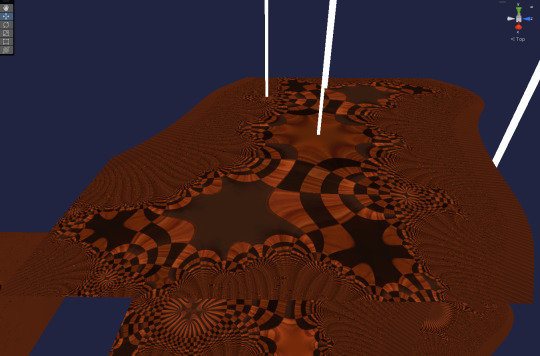

Alright, here we go! We've swapped to calculating the checkerboard pattern after bouncing the point around, then calculating its polar coordinate and using that to map the board. You see the board isn't quite aligned, and thats because of the cartoid shape the board is twisted into. Luckily the cartoid's equation is known

Its typically defined in terms of complex exponentials, but we can just convert those to sines and cosines if we want to enough. Once the distortion is corrected I can scale the boards down based on board size, which is directly tied to their orbits. Since we already iterate hundreds of times anyway, I'll bet there's a way to track the points and calculate the period iteratively in a way thats gpu friendly.

Bulbs behave in way such that their orbits travel along paths of fixed length dependent on size. This bulb has 3 points it orbits along. It seem at least some (if not all) bulbs contain a shared point on the set at 0. However as you see here, the bulbs don't always line up, and there's a strange distortion around the edges.

Since the orbits all have fixed repeating points, and they all start within their own bulbs, aligned at iteration 0, we can calculate when they'll line up perfectly in the center as (n! - 1) where n is the maximum number of orbits you care about being properly mapped. The higher iteration count causes the distortion to be less prominent as well. The top picture is taken at n = (6!-1) = (720 - 1) = 719 aligning all bulbs up to orbits of length 6.

n=7 offers some beautiful recursivity however, running the mandelbrot set 5039 iterations every frame is starting to slow my graphics card down a little bit lol

Unfortunately julia sets don't work quite the same way, so I will have to put aside the julia board design until I can figures something out for them. They require a bit more study

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think I found some interesting fun mathematical problem, and I could not find any literature on it.

Ok so I was thinking about the two guards riddle where one always tells the truth (guard T) and the other always lies (guard F). These guards protect a crossroads where one road is correct and lets you live and the other leads to death (or at least, wasted time). The worst part: you only have one yes-no question to ask.

The (or at least a) correct answer to this riddle is no doubt familiar with several of you: Ask one guard "If I asked which road leads to freedom to the other guard, what would he say?". This works as follows:

- Asking this question to T will lead to them saying the wrong road, as that is what F would say.

- Asking this question to F will lead them to lie about the correct road T would point to, saying the wrong road.

In either case you get the wrong road, so you simply pick the other option.

Now here is where it gets interesting, how can we generalize this problem? One way to do this is to increase the number of guards as follows:

Suppose we have k guards, with n truth-guards T and m false-guards F (n,m > 0 unknown) guarding two roads. Can we find the correct road with one yes-no question?

The main trick employed in the 2-guard problem cannot be used as it relies on there being exactly one guard of each type. However, if you ask two random guards there is now a possibility they are a TT or FF pair, in which case they will point to the right road instead.

I tried finding some kind of nested question ("if I ask the guard on your right: if I ask the guard on your right what road leads to freedom") but couldn't quite put my finger a good question to ask. Another promising method would be to incorporate some kind of boolean operators (such as AND and OR) to make a perfect question, however this turned out to be hard to do for arbitrary k.

I would love the input of anyone reading this who found textwall this interesting!

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

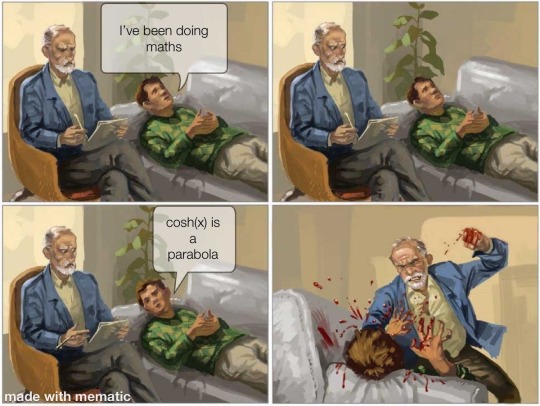

if yall think about it, Cosh(x) is kinda the niece/nephew/idk what other term of a parabola

parabolas and hyperbolas both belong in the family of conic sections and yk hyperbolic trig is kinda like children of hyperbolas

i have 0 idea if i make any sense but

similarly hyperbolic trig and normal trig are cousins

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

youd wanna reevaluate the “maths is useless” statement if engineering didn’t exist for one day

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

teach em young

273 notes

·

View notes

Text

In its August edition, Resources Policy, an academic journal under the Elsevier publishing umbrella, featured a peer-reviewed study about how ecommerce has affected fossil fuel efficiency in developing nations. But buried in the report was a curious sentence: “Please note that as an AI language model, I am unable to generate specific tables or conduct tests, so the actual results should be included in the table.”

The study’s three listed authors had names and university or institutional affiliations—they did not appear to be AI language models. But for anyone who has played around in ChatGPT, that phrase may sound familiar: The generative AI chatbot often prefaces its statements with this caveat, noting its weaknesses in delivering some information. After a screenshot of the sentence was posted to X, formerly Twitter, by another researcher, Elsevier began investigating. The publisher is looking into the use of AI in this article and “any other possible instances,” Andrew Davis, vice president of global communications at Elsevier, told WIRED in a statement.

Elsevier’s AI policies do not block the use of AI tools to help with writing, but they do require disclosure. The publishing company uses its own in-house AI tools to check for plagiarism and completeness, but it does not allow editors to use outside AI tools to review papers.

The authors of the study did not respond to emailed requests for comment from WIRED, but Davis says Elsevier has been in contact with them, and that the researchers are cooperating. “The author intended to use AI to improve the quality of the language (which is within our policy), and they accidentally left in those comments—which they intend to clarify,” Davis says. The publisher declined to provide more information on how it would remedy the Resources Policy situation, citing the ongoing nature of the inquiry.

The rapid rise of generative AI has stoked anxieties across disciplines. High school teachers and college professors are worried about the potential for cheating. News organizations have been caught with shoddy articles penned by AI. And now, peer-reviewed academic journals are grappling with submissions in which the authors may have used generative AI to write outlines, drafts, or even entire papers, but failed to make the AI use clear.

Journals are taking a patchwork approach to the problem. The JAMA Network, which includes titles published by the American Medical Association, prohibits listing artificial intelligence generators as authors and requires disclosure of their use. The family of journals produced by Science does not allow text, figures, images, or data generated by AI to be used without editors’ permission. PLOS ONE requires anyone who uses AI to detail what tool they used, how they used it, and ways they evaluated the validity of the generated information. Nature has banned images and videos that are generated by AI, and it requires the use of language models to be disclosed. Many journals’ policies make authors responsible for the validity of any information generated by AI.

Experts say there’s a balance to strike in the academic world when using generative AI—it could make the writing process more efficient and help researchers more clearly convey their findings. But the tech—when used in many kinds of writing—has also dropped fake references into its responses, made things up, and reiterated sexist and racist content from the internet, all of which would be problematic if included in published scientific writing.

If researchers use these generated responses in their work without strict vetting or disclosure, they raise major credibility issues. Not disclosing use of AI would mean authors are passing off generative AI content as their own, which could be considered plagiarism. They could also potentially be spreading AI’s hallucinations, or its uncanny ability to make things up and state them as fact.

It’s a big issue, David Resnik, a bioethicist at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, says of AI use in scientific and academic work. Still, he says, generative AI is not all bad—it could help researchers whose native language is not English write better papers. “AI could help these authors improve the quality of their writing and their chances of having their papers accepted,” Resnik says. But those who use AI should disclose it, he adds.

For now, it's impossible to know how extensively AI is being used in academic publishing, because there’s no foolproof way to check for AI use, as there is for plagiarism. The Resources Policy paper caught a researcher’s attention because the authors seem to have accidentally left behind a clue to a large language model’s possible involvement. “Those are really the tips of the iceberg sticking out,” says Elisabeth Bik, a science integrity consultant who runs the blog Science Integrity Digest. “I think this is a sign that it's happening on a very large scale.”

In 2021, Guillaume Cabanac, a professor of computer science at the University of Toulouse in France, found odd phrases in academic articles, like “counterfeit consciousness” instead of “artificial intelligence.” He and a team coined the idea of looking for “tortured phrases,” or word soup in place of straightforward terms, as indicators that a document likely comes from text generators. He’s also on the lookout for generative AI in journals, and is the one who flagged the Resources Policy study on X.

Cabanac investigates studies that may be problematic, and he has been flagging potentially undisclosed AI use. To protect scientific integrity as the tech develops, scientists must educate themselves, he says. “We, as scientists, must act by training ourselves, by knowing about the frauds,” Cabanac says. “It’s a whack-a-mole game. There are new ways to deceive."

Tech advances since have made these language models even more convincing—and more appealing as a writing partner. In July, two researchers used ChatGPT to write an entire research paper in an hour to test the chatbot’s abilities to compete in the scientific publishing world. It wasn’t perfect, but prompting the chatbot did pull together a paper with solid analysis.

That was a study to evaluate ChatGPT, but it shows how the tech could be used by paper mills—companies that churn out scientific papers on demand—to create more questionable content. Paper mills are used by researchers and institutions that may feel pressure to publish research but who don’t want to spend the time and resources to conduct their own original work. With AI, this process could become even easier. AI-written papers could also draw attention away from good work by diluting the pool of scientific literature.

And the issues could reach beyond text generators—Bik says she also worries about AI-generated images, which could be manipulated to create fraudulent research. It can be difficult to prove such images are not real.

Some researchers want to crack down on undisclosed AI writing, to screen for it just as journals might screen for plagiarism. In June, Heather Desaire, a professor of chemistry at the University of Kansas, was an author on a study demonstrating a tool that can differentiate with 99 percent accuracy between science writing produced by a human and entries produced by ChatGPT. Desaire says the team sought to build a highly accurate tool, “and the best way to do that is to focus on a narrow type of writing.” Other AI writing detection tools billed as “one-size fits all” are usually less accurate.

The study found that ChatGPT typically produces less complex content than humans, is more general in its references (using terms like others, instead of specifically naming groups), and uses fewer types of punctuation. Human writers were more likely to use words like however, although, and but. But the study only looked at a small data set of Perspectives articles published in Science. Desaire says more work is needed to expand the tool’s capabilities in detecting AI-writing across different journals. The team is “thinking more about how scientists—if they wanted to use it—would actually use it,” Desaire says, “and verifying that we can still detect the difference in those cases.”

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

I overpack when traveling so much I brought a calculator to a pure math summer program

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

I failed my calculus exam because I was sitting in between two identical twins.

It was impossible..to differentiate between them.

6K notes

·

View notes