Text

“CECI N’EST PAS UNE VAGINE”

Subscribed

The story is well known: in Metz, an incident occurred at the exposition of art works linked to Jacques Lacan. Two feminists staged a protest in front of Gustave Courbet’s The Origin of the World owned by Lacan; Deborah de Robertis wrote ‘MeToo’ on the painting which depicts a headless torso of a sexually aroused naked woman’s body, focused on her hairy vulva. The title of a predominant feminist reaction tells it all: “Hurrah for the Courbet vandals: defacing the vulva painting is basic feminism” – de Robertis “is right to think the painting is misogynistic: the model doesn’t even have a face!”[1]

Are things really so clear and simple? While fully respecting the feminist objections as well as rejecting the traditionalist academic disdain for the de Robertis’s act, I think things are more complex. Yes, there is a long history of a woman’s dismembered by a (male) painter. Recall “A Woman Throwing a Stone” (Picasso, 1931): the distorted fragments of a woman on a beach throwing a stone are, of course, a grotesque misrepresentation, if measured by the standard of realist reproduction; however, in their very plastic distortion, they immediately/intuitively render the Idea of a “woman throwing a stone,” the “inner form” of such a figure. Upon a closer look, one can easily discern the steps of the process of (what Husserl would have called) “eidetic reduction” of the woman to her essential features: hand, stone, breasts… this painting thinks, it performs the violent process of tearing apart the elements which, in their natural state, co-exist in reality. However, the problem is WHAT does this painting think – one should not forget that it was made by a male painter tearing apart a woman’s body…

So let’s begin with politics. Courbet was imprisoned for six months in 1871 for his involvement with the Paris Commune and lived in exile in Switzerland from 1873 until his death four years later. As for the fact that the torso is headless, we should remember that back in 2014, de Robertis already performed a feminist act in Musee d’Orsay: in front of the same painting, she sat down with her legs widely spread, fully exposing her vulva to the spectators.[2] This confrontation of the real displayed vagina with her fantasmatic double on a painting produces the effect of "This is not a vagina," like that of "This is not a pipe" in the famous Magritte painting - the scene in which a real person is shown side by side with the ultimate image of what she is in the fantasy for the male Other. But is a woman really more “objectivized” when painted as a headless torso?

To grasp what is happening here, on should recall the paradigmatic hard-core sexual position (and shot) which is easy to identify: the woman is lying on her back with her legs spread wide backwards and with her knees above her shoulder; the camera is in front, showing the man’s penis penetrating her vagina (the man’s face is as a rule invisible, he is reduced to an instrument), but what we see in the background between her thighs is her face in the thrall of orgasmic enjoyment. This minimal “reflexivity” is crucial: if we were just to see the close-up of penetration, the scene would soon turn boring, disgusting even, more of a medical showcase – one has to add the woman’s enthralled gaze, the subjective reaction to what is going on. Furthermore, this gaze is as a rule not addressed at her partner who is doing it but directly at us, viewers, confirming to us her enjoyment – we, spectators, clearly play the role of the big Other who has to register her enjoyment. The pivot of the scene is thus not male (her sexual partner’s or the spectator’s) enjoyment: the spectator is reduced to a pure gaze, the pivot is woman’s enjoyment (staged for the male gaze, of course). The sad irony here is that the very fact that the woman is not “objectivized” but rendered as a subject makes her humiliation worse: she has to fake her enjoyment. Being compelled to enact fake subjective engagement is much worse than being reduced to an object.

So, back to the photo of the painting and the “real” de Robertis displaying her vulva: the paradox is that, no matter what her intentions were, the real de Robertis displaying her vulva is much closer to pornography than Courbet’s painting precisely because her vulva is accompanied by her gaze (her head looking at us), while the effect of Courbet’s painting is much more disturbing – why, precisely? While it is not, of course, a feminist painting in any sense (it clearly addresses a male gaze), it clearly renders the deadlock (or dead end) of the traditional realist painting, whose ultimate object - never fully and directly shown, but always hinted at, present as a kind of underlying point of reference - was the naked and thoroughly sexualized feminine body as the ultimate object of male desire and look. The exposed feminine body functioned here in a way similar to the underlying reference to the sexual act in the classic Hollywood, best described by the famous instruction of the movie tycoon Monroe Stahr to his scriptwriters from Scott Fitzgerald's The Last Tycoon:

"At all times, at all moments when she is on the screen in our sight, she wants to sleep with Ken Willard. ... Whatever she does, it is in place of sleeping with Ken Willard. If she walks down the street she is walking to sleep with Ken Willard, if she eats her food it is to give her enough strentgh to sleep with Ken Willard. But at no time do you give the impression that she would even consider sleeping with Ken Willard unless they were properly sanctified."

The exposed feminine body is thus the impossible object, it functions as the ultimate horizon of representation whose disclosure is forever postponed - in short, it functions as the Lacanian incestuous Thing. Its absence, the Void of the Thing, is then filled in by "sublimated" images of beautiful, but not totally exposed, feminine bodies, i.e. by bodies which always maintain a minimum of distance towards That. But the crucial point (or, rather, the underlying illusion) of the traditional painting is that the "true" incestuous naked body nonetheless waits there to be discovered - in short, the illusion of traditional realism does not reside in the faithful rendering of the depicted objects; it rather resides in the belief that, BEHIND the directly rendered objects, there effectively IS the absolute Thing which could be possessed if we were only able to discard the obstacles or prohibitions that prevent access to it.

What Courbet accomplished in his “Origin” is the gesture of radical desublimation: he made the risky move and simply went to the end by way of directly depicting what the previous realistic art was just hinting at as its withdrawn point of reference - the outcome of this operation, of course, was the reversal of the sublime object into abject, into an abhorring, nauseating excremental piece of slime. (More precisely, Courbet masterfully continued to dwell at the very blurred border that separates the sublime from the excremental: the woman's body in "L'origine" retains its full erotic attraction, yet it becomes repulsive precisely on account of this excessive attraction.) Courbet's gesture is thus a dead end: the dead end of the traditional realist painting - but precisely as such, it is a necessary "mediator" between traditional and modernist art, i.e. it stands for a gesture that had to be accomplished if we are to "clear the ground" for the emergence of the modernist "abstract" art. How?

With Courbet, we learn that there is no Thing behind its sublime appearance, that if we force our way through the sublime appearance to the Thing itself, all we get is a suffocating nausea of the abject - so the only way to reestablish the minimal structure of sublimation is to directly stage THE VOID ITSELF, the Thing as the Void-Place-Frame, without the illusion that this Void is sustained by some hidden incestuous Object. One can now understand in what precise way, and paradoxical as it may sound, Malevitch's "Black Square" as the seminal painting of modernism is the true counterpoint to (or reversal of) "L'origine": in Courbet, we get the incestuous Thing itself which threatens to implode the Clearing, the Void in which (sublime) objects (can) appear, while in Malevitch, we get its exact opposite, the matrix of sublimation at its most elementary, reduced to the bare marking of the distance between foreground and background, between a wholly "abstract" object (square) and the Place that contains it. The "abstraction" of the modernist painting is thus to be conceived as a reaction to the over-presence of the ultimate "concrete" object, the incestuous Thing, that turns it into a disgusting abject, i.e. that turns the sublime into an excremental excess.

So far from being a simple male-chauvinist depiction of the object of desire, Courbet’s “Origine” confronts the male desire with its deadlock: what you really desire is a headless monster, and it is your gaze (sustained by desire) which decapitates the woman.

0 notes

Text

happy birthday Kant

Monday marks the 300th anniversary of Immanuel Kant’s birth. Kant is far from dead today—on the contrary, his thought is more than ever enabling us to see in a new way the horrors of the 20th century, not least the Shoah. Those who perceive the Shoah as the ultimate manifestation of radical evil seem to obtain an argument in Jacques Lacan’s thesis on “Kant avec Sade”—the formula “Kant with Sade” effectively names the ultimate paradox of modern ethics, positing an equation between the two radical opposites: Kant’s sublime, disinterested ethical attitude is somehow identical to, or overlaps with, the unrestrained indulgence in pleasurable violence associated with the Marquis de Sade.

A lot is at stake here: Is there a line from Kantian ethics to the Auschwitz killing machine? Are the Nazis’ concentration camps and their mode of killing—as a neutral business—the inherent terminus of the enlightened insistence on the autonomy of reason? Is there some affinity between Kant avec Sade and Fascist torture as portrayed by Pier Paolo Pasolini’s film version of 120 Days in Sodom, which transposes the story into the dark days of Mussolini’s Salò republic?

The link between Sade and Kant was first developed by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer in the famous Excursion II (“Juliette, or Enlightenment and Morality”) of the Dialectics of Enlightenment. Adorno’s and Horkheimer’s fundamental thesis is that “the work of Marquis de Sade displays the ‘Reason which is not led by another agency,’ that is to say, the bourgeois subject, liberated from a state of not yet being mature.” Some 15 years later, Lacan (unaware of Adorno’s and Horkheimer’s version of the argument) also developed the notion that Sade is the truth of Kant, first in his Seminar on The Ethics of Psychoanalysis (1958-59), and then in an écrit of 1963.

Adorno and Horkheimer located Sade in the long tradition of the orgiastic-carnivalesque reversal of the established order: the moment when the hierarchical rules are suspended, and “everything is permitted.” This primordial jouissance, recaptured by the sacred orgies is, of course, the retroactive projection of the alienated human state: It never existed prior to its loss. The point is that Sade announced the moment when, with the emergence of bourgeois Enlightenment, pleasure itself lost its sacred-transgressive character and was reduced to a rationalized instrumental activity. That is to say, according to Adorno and Horkheimer, the greatness of Sade was that, on behalf of the full assertion of earthly pleasures, he not only rejected any metaphysical moralism, but also fully acknowledged the price one has to pay for this rejection: the radical intellectualization-instrumentalization-regimentation of sexual activity intended to bring pleasure. Here we encounter the content later baptized by Herbert Marcuse’s “repressive desublimation”: After all the barriers of sublimation, of cultural transformation of sexual activity, are abolished, what we get isn’t raw, brutal, passionate, satisfying animal sex, but on the contrary, a fully regimented, intellectualized activity comparable to a well-planned sporting match.

The Sadean protagonist isn’t an animalistic brute, but a pale, cold-blooded intellectual much more alienated from the true pleasure of the flesh than is the prudish, inhibited lover. What gives pleasure to him (or her) isn’t sexuality as such, but the activity of outstripping rational civilization by its own means, that is, by way of thinking (and practicing) the unfolding of its logic to the end. So far from being an entity of full, earthly passion, the Sadean hero is fundamentally apathetic, reducing sexuality to a mechanically planned procedure deprived of the last vestiges of spontaneous pleasure or sentimentality. What Sade takes into account is that pure bodily sensual pleasure and spiritual love aren’t simply opposed, but dialectically intertwined: There is something deeply “spiritual,” spectral, sublime about a really passionate sensual lust—and vice versa, as mystical experience teaches us—so that the thorough “desublimation” of sexuality also thoroughly intellectualizes it, changing an intense pathetic bodily experience into a cold, apathetic mechanic exercise.

How, then, does Lacanian thought stand in regard to the Adorno-Horkheimer version of Kant avec Sade (that is, of Sade as the truth of Kantian ethics)? For Lacan, too, Sade deployed the inherent potential of the Kantian philosophical revolution, although Lacan gave to this a somewhat different twist: His point is that Sade honestly externalized the Voice of Conscience (which, in Kant, attests the subject’s full ethical autonomy) in the Executioner who terrorizes and tortures the victim….

But was this really some path-breaking insight? Today, in our post-idealist Freudian era, doesn’t everybody know what the point of the “with” is? Don’t we all appreciate that the truth of Kant’s ethical rigorism is the sadism of the Law, i.e., Kantian Law is a superego agency that sadistically enjoys the subject’s deadlock, his inability to meet its inexorable demands, like the proverbial teacher who tortures pupils with impossible tasks and secretly savors their endless failings? Lacan’s point, however, is the exact opposite of this first association: It wasn’t Kant who was a closet sadist, but the Marquis de Sade who was a closet Kantian.

In contrast to this, “diabolical” evil does designate a specific type of evil acts: acts that aren’t motivated by any pathological motivation, but are done “just for the sake of it,” elevating evil itself into an a priori non-pathological motivation—something akin to Poe’s “imp of perversity.” While Kant claimed that “diabolical evil” can’t actually occur (it isn’t possible for a human being to elevate evil itself into a universal ethical norm), he insisted on its abstract possibility. Interestingly enough, the concrete case he mentioned (in Part I of his Metaphysics of Morals) is that of the judicial regicide, the murder of a king executed as a punishment pronounced by a court: Kant claimed that, in contrast to a simple rebellion in which the mob kills only the person of a king, the judicial process that condemns to death the king (this embodiment of the rule of law) destroys from within the very form of the rule of law, turning it into a terrifying travesty—which is why, as Kant put it, such an act is an “indelible crime” that can’t ever be pardoned. However, in a second step, Kant desperately argued that in the two historical cases of such an act (under Cromwell and in revolutionary France), we were dealing just with a mob taking revenge…. Why this oscillation and classificatory confusion? Because, if he were to have asserted the actual possibility of “diabolical evil,” he would have found it impossible to distinguish it from the good: Since both acts would be non-pathologically motivated, the travesty of justice would become indistinguishable from justice itself.

Yet horrors like Shoah are not a category of radical evil. To see this, we should turn to the category of impersonal beliefs elaborated by Robert Pfaller: beliefs that function as a social fact and determine how we act, even though (almost) no one directly accepts them at a personal level. The usual excuse of individuals is something like: “I know it’s probably not true, but I follow the rules, because they are constitutive of my community.” To be clear: This impersonal belief doesn’t exist independently of the subject (who believes or presupposes another to believe)—it exists (or rather, it is operative) only as presupposed by the subject who pretends not to believe. The status of this impersonal belief is thus exactly that of the big Other: “I don’t believe… (but the big Other does, and for its sake, I have to act as if I do believe).” And one should posit that, in a parallel with impersonal belief, there is also something we should call impersonal enjoyment: enjoyment that can’t be attributed to individuals (as “subjects who directly enjoy”), but rather to some big Other. Such impersonal enjoyment is what characterizes perversion, which is why Lacan defined a pervert as the agent who conceives himself as the instrument of the Other’s enjoyment. This is precisely what Lacan alluded to in the final pages of his 11th Seminar:

The offering to obscure gods of an object of sacrifice is something to which few subjects can resist succumbing, as if under some monstrous spell. Ignorance, indifference, an averting of the eyes may explain beneath what veil this mystery still remains hidden. But for whoever is capable of turning a courageous gaze towards this phenomenon—and, once again, there are certainly few who do not succumb to the fascination of the sacrifice in itself—the sacrifice signifies that, in the object of our desires, we try to find evidence for the presence of the desire of this Other that I call here the dark God.

A pervert who operates under this “monstrous spell” and does what he does for the enjoyment of the divine Other isn’t a sleazy guy who enjoys torturing his victims; he is, on the contrary, a cold professional who does his duty in an impersonal way, for the sake of duty. The shift from an ordinary sadist to a true pervert is what sustains Hannah Arendt’s description of the change that occurred in the Nazi project when the Schutzstaffel (SS) supplanted the thuggish Sturmabteilung (SA) as the administrators of the concentration camps:

Behind the blind bestiality of the SA, there often lay a deep hatred and resentment against all those who were socially, intellectually, or physically better off than themselves, and who now, as if in fulfilment of their wildest dreams, were in their power. This resentment, which never died out entirely in the camps, strikes us as a last remnant of humanly understandable feeling. The real horror began, however, when the SS took over the administration of the camps. The old spontaneous bestiality gave way to an absolutely cold and systematic destruction of human bodies, calculated to destroy human dignity; death was avoided or postponed indefinitely. The camps were no longer amusement parks for beasts in human form, that is, for men who really belonged in mental institutions and prisons; the reverse became true: They were turned into ‘drill grounds,’ on which perfectly normal men were trained to be full-fledged members of the SS.

Adolf Eichmann wasn’t just a bureaucrat organizing the timetables of trains for the SS; he was in some sense aware of the horror he was organizing, but his distance toward this horror, his pretense that he was just a bureaucrat doing his duty, was part of his enjoyment. It was what added a surplus to his enjoyment—he enjoyed, but in a purely interpassive way, through the Other, the “dark god” to whom Sade referred as “the Supreme-Being-in-Evil” (“l'être suprême en méchanceté”). To put it in somewhat simplified terms, although an SS officer might have pretended (and could sincerely believe) to be working for the good (of his nation, ridding it of its enemies), the very way he did this (the brutality of the concentration camps) made him a bureaucrat of evil, an agent of what Hegel would have called the ethical substance (Sitten) of his nation. And it wasn’t just that the SS officer misunderstood the true greatness of his nation: The tension between the noble greatness of the idea of a nation and its dark underside is inscribed into the very notion of a nation. The Nazi idea of the German nation as an organic community threatened by Jewish intruders is in itself false—it forecloses immanent antagonisms that then return in the figure of the Jewish plot. The necessity to get rid of the Jews was thus inscribed into the very (Nazi) notion of German identity.

Things are similar with the new rightist populism. The contrast between Trump’s official ideological message (conservative values) and the style of his public performance (saying more or less whatever pops up in his head, insulting others, and violating all rules of good manners) tells a lot about our predicament: What sort of world do we inhibit, in which bombarding the public with indecent vulgarities presents itself as the last barrier to protect us from the triumph of the society in which everything is permitted and old values go down the drain? Trump is not a relic of the old moral-majority conservatism—he is to a much greater degree the caricatural inverted image of postmodern “permissive society” itself, a product of this society’s own antagonisms and inner limitations.

Adrian Johnston proposed “a complementary twist on Jacques Lacan’s dictum according to which ‘repression is always the return of the repressed’: The return of the repressed sometimes is the most effective repression.” Is this not also a concise definition of the figure of Donald Trump? As Freud said about perversion: In it, everything that was repressed, all repressed content, comes out in all its obscenity, but this return of the repressed only strengthens the repression. Hence, why there is nothing liberating in Trump’s obscenities. They merely strengthen social oppression and mystification. Trump’s obscene performances thus express the falsity of his populism: to put it with brutal simplicity, while acting as if he cares for the ordinary people, he promotes big capital. Totalitarian masters often discreetly admit that they are aware they have to employ brutal thugs for the job to be done, and that these thugs are sadists who enjoy their brutal exercise of power. But they are wrong in constraining pleasure to a “human factor” that spoils the purity of the structure: The brutal obscenity of enjoyment is immanent to the social structure; it is a sign that this structure is in itself antagonistic, inconsistent. In social life, too, surplus-enjoyment is needed to fill in the gap (“contradiction”) that traverses social structure.

Is it not obvious, then, that Kant’s occluded view into the nature of evil can nevertheless shed great light on our century’s horrors, as well?

0 notes

Text

Day 32

Расцветать (verb, imperf.) - to bloom

Яблоня (noun, n.) - apple tree

Груша (noun, m.) - pear

Берег (noun, m.) - shore

Заводить (verb, imperf.) - to start/wind up/establish

Сизый - bluish/dove colored

Орёл (noun, m.) - eagle

Беречь (verb, imperf.) - to protect/take care of/save

Девичий (adj.) - girly/maiden

Вслед (adv.) - after/following (smth.)

Боец (noun, m.) - fighter

Пограничье (noun, n.) - borderland

Поплыть (verb, perf.) - to swim

Сменять (verb, imperf.) - to change

Допить (verb, perf.) - to drink up

Дно (noun, n.) - bottom/underworld

Раненый (adj.) - wounded

Высота (noun, f.) height

Оглянуться (verb, perf.) - to look back

Срываться (verb, imperf.) - to break loose

Губа (noun, f.) - lip

Разрывать (verb, imperf.) - to tear/sever

Сотня - one hundred

Осколок (noun, m.) - splinter

Полететь (verb, perf.) - to fly

Прочь - away

Долой - down/away/off with smth.

Край (noun, n.) - edge

Пропасть (noun, f.) - divide/abyss/divide

Songs: Катюша by Galina Jelisejewa & Беги by Sevak

45 notes

·

View notes

Video

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

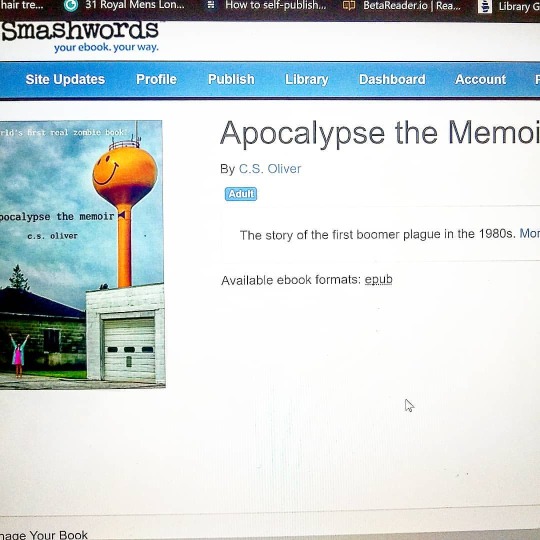

That time I wrote a book about a boomer plague. https://www.instagram.com/p/B-ABSzSn1HA/?igshid=hh0g36vhondx

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

все хорошо (at Düsseldorf, Germany) https://www.instagram.com/p/B9FlF4hnhpf/?igshid=1017bump58z13

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Working. (at Stratford, Ontario) https://www.instagram.com/p/B8HbskcndyX/?igshid=hpu53bjcp3l2

0 notes

Photo

"and I'll probably be the last to know because I don't go on the internet no more" (at Victory Column Tiergarten Park) https://www.instagram.com/p/B52MDDEnOl3/?igshid=1v36k5lp49wpq

0 notes

Video

at Пивная Диета / Beer Diet https://www.instagram.com/p/B2CKs9wnTUz/?igshid=evr5a9oj3faa

0 notes

Video

at Linnankellari https://www.instagram.com/p/B1MeeZ4A-Zy/?igshid=1oltpw3qb4fh9

0 notes

Photo

ATTENTION: Found good thing in arctic. (at Kiruna, Sweden) https://www.instagram.com/p/B0DVqe2nX86/?igshid=1rarrw71ij7v8

0 notes

Photo

The main attraction here: Fevered Gear-swamped Tourists #tromso #$$$$ (at Tromsø, Norway) https://www.instagram.com/p/BzzWofVH1HJ/?igshid=8bvqaw9xo6c9

0 notes

Photo

What. (at Lapland (Finland)) https://www.instagram.com/p/Bzwsi1fHL5U/?igshid=xhexnkxp9hoc

0 notes

Photo

Take A Vacation To California Anytime (at Ботанический сад Петра Великого, Петербург) https://www.instagram.com/p/Bzjz9dun8aY/?igshid=1f90zeivgath0

0 notes

Photo

It means Pine Forest only. (at Sosnovyy Bor, Leningradskaya Oblast', Russia) https://www.instagram.com/urtellingalie/p/Byl4vgknaEf/?igshid=15uex8kkpailc

0 notes

Photo

Beach volleyball. (at Sosnovy Bor) https://www.instagram.com/urtellingalie/p/Byk32CvHn4D/?igshid=o2g28pn4sjkr

0 notes