Photo

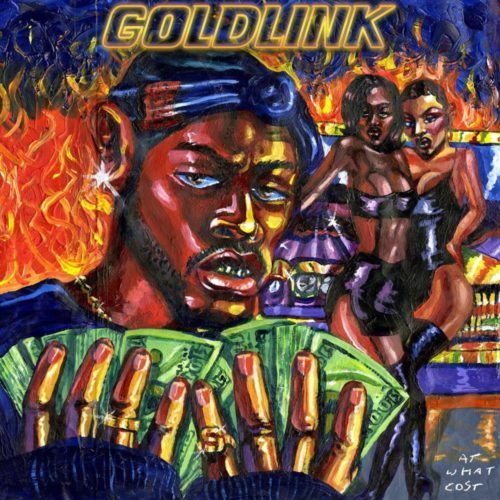

GoldLink, At What Cost (2017)

Inhabiting a space turns it into a territory, with the stories, the experiences, the culture and everything else that’s brought to a specific area along with people sharing their life there. It all builds up to shape a given land, adding a history, customs as well as artistic expressions that turn into concepts and social representations. As such, growing in a place comes with the inevitable development of mental structures that are fitting the unique area’s background and its population. “There’s no place like home“ says the timeless phrase to capture this feeling and the hip-hop culture has long made this idiom a key concept of its own. Repping, putting one’s hood on the map, somehow feels like a mission to most rappers, from André 3000’s “the South got something to say“ declaration at the Source Awards in 1995 to GoldLink’s At What Cost in 2017; the tradition goes on.

Born D’Anthony Carlos and raised between D.C. and Maryland, GoldLink is as DMV (D.C., Maryland, Virginia) as it gets. Since he started to rise, with 2015 mixtape The God Complex and the XXL Freshman cover of the same year, the rapper with a pimp-inspired stage name has been dedicated to craft a D.C. or more broadly a DMV sound. Yet At What Cost is his best attempt at it and its most straightforward, as demonstrated by Mya’s chorus on “Roll Call“:

“No matter where I go

So I'm always on the go

Gonna go back

'Cause it made me.“

Making the soundtrack of a city requires to fill it with a complex sonic landscape. Voices, accents, slangs, culture, noises, details and the imagery are among the many elements that compose the audible life of a given place. Such work echoes the profound nature of rap however. Collecting pieces of culture and vocal or linguistic parts to then blend them together. GoldLink follows that aforesaid dynamic in what feels like a collage of DMV. Talking to magazine Vibe, the rapper expressed that his “biggest influence is“ his “city“ and nothing illustrates this better than the myriad of guests on the album (Wale, Shy Glizzy, Radiant Children, Mya…), each representing facets of this triangle of states, from the way they stress on the words to their musical influences. Even more striking is the song “Kokamoe Freestyle“, which takes its name from a famous local figure that’s been sharing raps in a D.C. bus for years.

Narrating D.C., especially, requires storytelling skills that GoldLink shows with the fascinating biographical aspect of his music, already shown on his previous releases. Listening to his new album and notably “Meditation“, one can imagine the colder months in the city, with a crowd hanging near a basketball field looked upon by naked trees. Close-by, bass rattles the surrounding cars on a parking lot near brick houses. The streets can almost be visualized as the rapper names a dozen of neighborhoods and famous streets throughout the fourteen tracks. Along the same way, interludes and lyrical particularities are used to exhibit the city in all its uniqueness.

All in all, this is what At What Cost is about: life in the streets of the DMV area. Inspired by the rapper’s everyday life, the stories tell as much about him and his addiction to sex or his thirst for money and a better life than the underground tales go-go sound’s birthplace — the DMV inspirations are also sonic ones that the album succeeds in mixing together into one complex sound.

The eclectic nature of the area is summed up by the evolution between GoldLink’s former releases and this one. While he and his producer Louie Lastic have carved before what they called themselves the “future bounce“ sound, they only kept some of its architecture to create this album’s sonic signature, along with varied producers such as Kaytranada or members of The Internet. The overall upbeat and groovy dimension remain, joined by the welcome and compulsory regional funk influence. Go-go, more specifically, has been the area’s soundtrack since the 1970s. “Some Girl“ clearly pays homage to the musical genre while “Hands On Your Knees“ takes the listener to a go-go party, vibrating along the conga drums. Being a dancehall music that puts the accent on live audience call-and-response and improvised percussions, the go-go sound is full of energy and unequivocally invites to dance, together with its vibrant rhythm.

The sound is colored, upbeat and full of tropical percussion that GoldLink describes as “tribal“ to explain the area’s identity based on drums and the feeling of a community that accompanies it. Electronic music meets funk, soul and R&B vibes such as on “Herside Story“. The production remains minimal however to let the details and the images shine, although the voice melts in the background, painting GoldLink as a modern Chuck Brown, emceeing a crowded party, as shown on single “Crew“’s cover. This is, to sum it up, audible jiggling in both the lyrics and the live instrumentation sounding production with futuristic dashes appearing under Montreal producer Kaytranada’s notes.

Darius Moreno painted the album’s as well as the single’s covers and his art is an important part of the DMV kaleidoscopic vision. The rich color scheme he uses echoes the dizzying mix of sounds that builds D.C. and its area: the industrial and electronic concrete sounds on “Kokamoe Freestyle“, the cloudy yet boasting atmosphere of “Crew“, the overall go-go sound or the intimate and gospel sounding closer, “Pray Everyday (Survivor's Guilt)“.

The club culture, linked to funk and to the ballroom community, is also essential to the painting. Full of luscious and sexual lyrics, the album brings to mind Moreno’s eccentric and warm images of the local youth that rises the temperature in the “Chocolate City“ with its LGBT friendly subculture and parties. Repping with pride the DMV is also a way for GoldLink to praise its women. The street-savvy narratives are thus soaked with exaggerated sexual braggadocio, going from butter smooth dancing to deeply misogynistic stunts while referencing a couple heartbreaks. Peeling the city like he seems to undress girls on “Have You Seen That Girl“, the rapper shouts out to the hoods he respects by exploring the different women that live there. Along the same way and as GoldLink relates his past and future love affairs throughout the album, Shy Glizzy adds an energetic verse about luring fancy girls from the richer neighborhoods to his dangerous Southeast D.C. on the album’s standout track and DMV anthem “Crew“, on which Baltimore Brent Faiyaz also sings .

Yet, the sensual sheen reveals darker spots in its cracks. At the end of “Meditation“, GoldLink appears to be caught in a fight with gunshots as he is flirting with a seducing woman from a rival hood. The scene could have taken place in legendary Club U since the DMV and the go-go culture is also sadly linked to violence. This modern Romeo and Juliet story echoes more gloomy lyrics found on the album where the violence balances the somewhat idyllic views of the area, as shown by “We Will Never Die“ where the term “go-go“ sounds like a stammering pronunciation of goddamn that regrets the gone friends. D.C. remains D.C. after all and gun shots as well as death are part of the city’s and of the area’s soundtrack too.

In a place where death can be found at the corner of the street, religion, family and good times seem to be the best armor. On the album’s last song, GoldLink raps over a gospel infused production, reminding himself to pray, like his mother used to tell him, while a choir slowly joins him one line at a time. The song ends however with a prayer that refreshes the rivalry between DMV’s territories, instead of calling for peace. Similarly, taking a new spin on the classic gospel song “Shake The Devil Off“ that GoldLink and his friends grew up with, Jazmine Sullivan sings on the chorus of “Meditation“ the somewhat profane “Shake, shake, shake“, “in the name of dancehall“. In the end, music, sex and violence outshine the rest. This is DMV.

0 notes

Photo

Payroll Giovanni, PayFace (2017)

The engine of a fancy car is roaring in the well-named Motor City. In a split second, it is gone, on its way to a fancier suburb. The snow falls vigorously over the city and a wanderer cannot figure out if it is snow indeed or cocaïne falling from skilled pockets towards noses of drug-addicts. The snowflakes are reflecting sparks of light on the ice that both the shady roads and the drug dealers are wearing. Patched up brick houses are aligned and seem inhabited, if not by the ghosts of an era when the dilapidated city was not used to its electricity shutting down.

Some of them are known as spot houses —similar to the trap ones found in Atlanta—, home to a crowd of drug dealers trying to pay their bills in a town that has gone bankrupt. Among such a gloomy atmosphere, the drug addicts are many. Strolling through Detroit’s abandoned neighborhoods, photographer Matt Sukkar cannot believe what he sees: “There’s all these burnt-out, leftover structures that haven’t been inhabited in such a long time. There’s feral animals; It’s like something out of I Am Legend.”

Yet a new life seems to emerge, based on autonomy and local activities, among which community gardens pursue the idea behind the popular Farm-A-Lot program. Local hero Icewear Vezzo walks by his rib and steak joint, Chicken Talk, his latest investment meant to revitalize Detroit, greetings locals that recognize the rapper turned business man when the fancy car heard earlier thrums by him accompanied by the sound of insults vanishing in the wind. Rivalry between clans remains strong here.

In the car, the Doughboyz are making sure that they do run the city, as they unequivocally named their first mixtape. Rolex watches and shiny rims are here to tell everybody they’re around. The driver, Payroll Giovanni, also used to live in these streets but he did everything to leave them behind. “The first step to gettin' money is just get up off your ass“, he says on “Hustle Muzik 3“, while his BYLUG chain speaks for itself by the number of diamonds on it: Boss Your Life Up.

Looking back at his past, Payroll is urging everybody to leave the streets, accusing those still there to be lazy or not good enough to merit his respect, in a cynical Darwinian arrogance. Putting on his most expensive fur coat, he sees himself as a godfather, giving the guidelines to succeed:

“Get money, get power, get clout n***

Get M's, get ends, get out n***

Take losses, bounce back, don't pout n***

Stay away from small minded big mouthed n***.“

With cold-as-ice irony, he depicts Detroit and its life in the streets, explaining on “Started Small Time“ that he “wasn’t a home owner but owned a crack house“. Now a home owner, he picks up the torch from his elders, amongst whom is Blade Icewood. Recalling the way he grew up, he reveals the heritage on the album’s cinematographic introduction: “Middleschool I was gettin' picked up in Lexuses / Corvettes and shit, raised by dealers with gold necklaces“. It’s now his turn to drive.

The local scene never got the boom Chicago got with the drill sound, although the talents here are countless. It might have to do with the obsession these rappers have for lost times, away from the hip and now generic trap sound of Atlanta, preferring warm southern textures like the mob music. On PayFace, Payroll endlessly raps about drug dealing, while Helluva embodies the spirit of 1980s Miami, eyeing at Moroder’s soundtrack for Scarface. The strength of the album thus relies on the clever balance between the self-aware impersonation of such myths and the sparks of cold rutted-concrete reality.

Saving himself from these streets is not enough for him though. After he and Cardo imagined themselves as Californian gangsters, grinning under the sun, counting the payroll, Giovanni takes on the unquenchable source of inspiration that Brian de Palma’s Scarface is. Still looking for warmth, Payroll leaves the sound and aesthetic of LA and its surroundings found on Big Bossin’ Vol.1 to go South-East, in Florida, where him and Detroit’s key producer Helluva mentally remake Tony Montana’s road to success. Wearing a long fur coat that would surely do well during a deadly Michigan winter, Payroll is trying to escape as much as he’s looking to bring Detroit gangsta rap to iconic levels.

As the rapper describes with pride the success of his business, the album gets colored with 80s vibes, reminiscent of Scarface’s gaudy visions of Miami. On “How We Move It“, Payroll and his gang describe their style to be linked straight from drug dealing, as implied by the pun on Montell Jordan’s original anthem. Bringing back the sung chorus, B Ryan follows a similar logic on “Shop“. By repeating the title of the song and by adding multiple singing voices, the hook is built on a musical structure that brings to mind both typical commercials from the 80’s as well as the sunny sounds from the US southern states that Payroll admires. The addictive melody of the R&B voice and the praising words celebrate Payroll Giovanni’s merchandise and his ability as a drug dealer. It is nothing else than a hotline bling for the bud lovers, turning the literal sense into a performative metaphor for Payroll’s rap, as well as painting him as a product himself, a figure that’s sitting next to Tony Montana.

However, just like the idol, Payroll remains as dark, with a M203 grenade launcher flow, telling us about the ordeals he went through, it sounds as if he’s saying: “You know what capitalism is? Getting fucked!“

0 notes

Photo

Shy Glizzy, Quiet Storm (2017)

On the 37th avenue in Southeast Washington DC, among the brick houses’ dried lawns, a group of people are gathered around a Toyota Corolla, negotiating the price for drugs with a crack addict prostitute while a luxury car drives by on the patched-up road, leaving fleeting notes of piano and heavy bass behind. Later that day, someone will be shot dead. “Welcome to DC baby!“

Far from the fake looking official sides of the city, DC seems to have two faces. The heavy political clownery weight with its always freshly painted monuments is ruled by the white house, whereas the large and unknown working class areas has given the city its title of “Chocolate City“. DC’s history is indeed linked to waves of black Americans coming to the city and enriching its multi-faceted culture. Marquis Amonte King grew up there, on Tre-7, DC’s area known to be one of the city’s roughest. Growing up as a shy kid, he saw it all: violence, drugs and poverty as well as hopes and disillusions, flashy cars and lifestyles. Telling the stories of forgotten masses that only existed by their absence to Trump’s inaugural speech felt vital to him and in a city trying to push away its poverty along with its black history, a voice that relates its gutter street life is precious.

After a few impressive mixtapes and a Grammy nomination for “Crew“ with the other DC rap hero Goldlink, Quiet Storm reveals the full potential of the paradoxical Shy / Jefe. While the latter is Spanish for “boss“, which leads the boastfulness found throughout the album, the shy side balances what would otherwise be a simplistic tale about money and romantic conquests.

Narrating the stories and the complexities of the street life and the contradictions that growing up in DC can be, Shy Glizzy oscillates between celebration and melancholy. The stories are centered around similar topics yet sound extremely varied, ranging from the acknowledgment of his success and his thirst for more, to a sensibility and a feeling of intimacy about those that have suffered. Naming streets and adding vivid details let Shy draw images of the “real DC“, strengthened by the raw emotion that’s delivered. In an interview with XXL Magazine, the rapper said along the same idea that “I want my fans to feel the energy, whether good or bad. I want them to soak it in and understand every word. It's genuine and that's all I want them to see it as“.

With his unconventional flow and charisma, Jefe develops a fascinating melodic flexibility to paint DC’s streets as well as himself. Following the somehow comforting sound of his whiny way of singing, the listener is caught in the fusion of Jefe’s voice and the rest of the songs’ structure as the rapper hops from a verse to a hook in a seamless manner. On Quiet Storm, the control over his vocal instrument never sounded as mastered as when Shy Glizzy creates tension between the lyrics, the gorgeous melodies that are crafted through his nasal voice and the productions from Cardo, Geraldo Live, TM88 or Zaytoven, among others. This unique vocal signature is all the more emphasized by the calm and minimal production, creating cloudy and ethereal atmospheres similar to what Barry Jenkins visually captured on Moonlight. Through the eyes of the rapper, the heavily autobiographic tales seem to be floating over the city, catching glimpses of the everyday lives of Shy’s neighbors and friends.

Showing his pride to come from the 37th avenue, the songs also highlight in a gloomy and depressive way the violence of his upbringing environment. On “Get Away“, a minor cord scale resonates and creates a blurry atmosphere, showing the tiresome that comes with the daily violence and the futility of his new expensive lifestyle. The cloudy synthwaves add to the escaping theme and deepen the melancholy. Shy Glizzy seems faraway, delivering a story about the humiliating everyday struggle in a DC that’s hidden. Along the melodic sensual trap productions, often using piano backed trap beats, the rapper seems to unfold a pop appeal with bragging flows and a rather typical materialistic imagery before a somber lament is ultimately revealed. The gloomy sonic landscape never leaves the songs’ instrumental parts either, whether the flow becomes aggressive or celebrating.

Death and danger have always been important patterns for Jefe, from the fascinating Law III’s “Funeral“ to Quiet Storm’s “Keep it Goin“. Ad-libs borrowed from Atlanta compliment his stories about girls, banknotes or success but also sound darker when it appears obvious that the rapper is trying to escape the always present sadness. Seemingly fighting against silence, the voice sounds maximal on “GG Worldwide“, conquering all the room as well as refreshing French philosopher Rousseau’s claim that silence leads to morbid sadness. Like a stone ricocheting on still water, Shy’s voice is echoing, as if words have to be repeated more than once to convey their meaning and as if the voice is fighting against its disappearance. Making traces seem vital on a gang anthem but the rapper seems full of despair when faced with the fact that nothing stays. Ultimately, the celebration sounds like a death chant: RIP 30 and all those that fell, y’all will be forever, he seems to say between the lines.

Everywhere on the album, wistfulness rises, leaking in a fragile image of success. On “Loving Me“, the braggadacio sounds more like a call for attention, an attempt to believe in a ready-made happiness and pride that’s delivered through a monotonous and rigid flow, while simple yet cold piano notes create a worrying ambiance in the background. Death is still glancing at the corner of the street and the line between a friend and an opp is thin as the listener is reminded throughout the album. The climax is reached on closer “Take Me Away“ —recorded alone at 5am— where angels seem to be mourning. The flashes are turned off for this requiem that’s brutally honest.

Melancholic nihilism is always on the verge to eat up everything as Shy talks with a similar tones about murders or wads of cash, yet emotions rise last minute to balance the whole, along with the warmth of family and friends. All in all, blood and determination remain the key word in such a picture: in a military type of attitude, the glizzy gang chant altogether that they’re soldiers, or more specifically paper soldiers.

0 notes

Photo

Tee Grizzley, My Moment (2017)

In Richard Donner’s The Goonies, Mouth declares about Detroit that it is “where Motown started“, before adding that “it’s also got the highest murder rate in the country“. Somehow, what appears at first glance as a paradoxical statement seems to announce that Detroit would be the most exciting rap scene in 2017. Payroll Giovanni, Lil Baby, Peezy, Sada Baby, Icewear Vezzo, BabyFace Ray or FMB DZ, among others, have all had their moments last year, each developing the Detroit’s style, which is mainly based on sinister gangster stories.

Crime, poverty, racism and riots are the horrific daily rhythm that the city vibrates on, along with its deep roots in various musical genres. Outside of the infamous rivalry between the east side and the west side of the city, Detroit has been and keeps being wrecked, whether it is by the public service’s slow but noticeable desertion or by the police’s violent relationship to the poorest neighborhoods. Crippled by the city’s economic situation, its population is thrown generation after generation into drug trafficking and misery, illustrating Ruby K. Payne’s concept of generational poverty, albeit also linked to racial tensions, as the 1967 12th Street riot clearly revealed it.

On Detroit’s Joy Road, in the “Skuddy Zone“, lost between Southfield and Evergreen, a ruined household has seen one of too many underprivileged and abused children growing up, living a daily life that does not seem so different than what happened during the Purple Gang era. Terry Sanchez Wallace is far from being a rapper at the time and he rather might wonder if he is having a nightmare or living one, when his mother is sent for 15 years to jail, due to drug trafficking. The same year, his father is shot and killed in the streets of Detroit. Again, a few years later, one of his uncles will also be shot in the head — Terry’s “Granny's eyes still ain't even dried yet“ will he reckon on his song “Secrets“.

Despite his life in the streets, the future rapper prodigy will go to college but as poverty soon catches him, he is sent to jail in the Central Michigan Correctional Facility in St. Louis, for stealing Rolex watches in a jewelry store, among other thefts. It is locked up that he’ll write his story, in a collection of diary-like tracks compiled on My Moment.

Fed with R&B through his cousins living with him at his grandmother’s, Tee Grizzley always got a soft spot for melodies and singing. However, the raw energy and the hard-hitting sounds that can be found on his breakthrough song “First Day Out“ is fitting his parallel life, the one happening in the streets and in jail. It is there that he got his nickname, while his dreads and his beard were out of control as well as his anger, similar to a grizzly bear. This hostility can be found throughout the entire mixtape, drowned in a typical Detroit flow that seems to contain too many words in a bar.

Filling his stories of the street life with vivid details, the rapper reveals the dark realm he’s known forever. Rapping about drug dealing and crimes, his voice sounds like a grunt from the depths, sometimes close and sometimes far, as if he was crouching in a cave (“Country“). A feeling of urgency comes in these tales, as Helluva’s masterful piano notes set the cadence of most of the songs. Being the shadow of the mixtape, the famous producer knits a murky yet emotive ambience (“How Many“, “Secrets“) that adds to the balancing tone of the songs — murders leave room for tributes and to prayers.

It is however on the Sonny Digital produced “Overlapped“ that the criminal intensity reaches its peak. The somber piano flirts with naked drums on which Tee’s voice sounds prophetic, creating an eerie atmosphere, as if somebody could be shot at any second. Marked with cynical lines, other songs paint a gloomy picture of the streets: “Last n*** we was beefin’ with, uh / Man, I can’t even think of what cemetery them n*** at / It’ll come to me later, it’s on the tip of my tongue“, he raps on “No Effort“.

The horror movie style production is however not meant to roll out shabby gangsta braggadocio. Instead, Tee Grizzley opens up the streets of Detroit in a surgically storytelling way, giving the listener an impressively authentic autobiography. The lyrics tackle various themes such as betrayal, friendship, ordeals and the US legal system. Opening up in the course of killing stories, Tee Grizzley lets the listener see through his eyes how he grew up and got into music, listening to his uncle rapping while performatively mimicking similar coming-of-age novella on the mixtape’s DIY yet impressive introduction.

Sporting Cartier glasses made out of buffalo horns, the rapper seems to gain super powers as he judges others’ realness, concluding that “everybody ain’t street“, the same way Raditz from Dragon Ball Z calculates his opponents’ strength. My Moment echoes indeed Lil Durk’s Only The Family mantra and it is no wonder why the two released a common mixtape, since the harrowing betrayals of Tee’s friends are narrated all over: “no letters or no pictures like a n*** just stopped livin’“ (“Real N***s“). In such a nightmare, friends and God are the only things the rapper can rely on.

Honest and thus somber, Tee Grizzley’s mixtape brings hard delivery and R&B vibes to tell a vivid diary about the streets with all their violence, lost ones and lost hopes, as well as too brief flashes of laughter or comfort in materialistic possession — “Red bottoms on my feet like my shoes got brake light“ he says on “No Effort“, adding luxury shoes to the Rolex watches he can now hopefully legally get. Tee Grizzley is definitely having his moment, and it’s a well-deserved one.

0 notes

Photo

Future, “Codeine Crazy“ (Monster, 2015)

The reflection of a tuxedo shines on a bottle of champagne, drowned in the steam of a freshly crushed ice. By its side, slouched in a grained leather luxurious armchair, the silhouette of Future is hardly noticeable in the overall scenery of a VIP club. Nothing but the ephemeral sparkles of light mirrored by his watch set with diamonds and his golden grillz give his presence away in an atmosphere that seems slowed down. Under his thick and dark sunglasses, the crooner dreams that he is in the middle of an upside down field, gazing at a purple sky about to collapse. The air almost feels like it is visible as it is so heavy, making his breathing difficult.

In the middle of this scene, which could either describe metaphorically a feeling of ease or a soul being gnawed on by anxiety and nothingness, Future exposes his swampy uneasiness and his desire of drug assisted suicide. “Codeine Crazy“, which closes the extraordinary dive into the abyss that Monster is, deals with these intoxications that eat up the body and the mind of the rapper while the TM88 production develops a muddy atmosphere that seems to materialize the effect given by the mix of codeine and promethazine — an alchemical process giving birth to the infamous syrup, also known as lean. Drunkenness, the loss of the intellect over emotions and impulses, is here as much of a theme as it is a pre-text to create and more generally to unfold a depressive aesthetic made in Texas.

The first bars display nothing but a confused scale, seemingly mimicking the feeling of half-drowsy half-euphoric when the purple drug kicks in. Everything appears to be slowing down even though nothing has yet started, the analgesic atmosphere evoking at once the chopped & screwed sound of Houston. Heavy and tired piano notes come to life and run during the whole song, helping to define the claustrophobic soundtrack of a bad trip along with low-pass filters that are as groggy as a brain swimming in dirty sprite. To counterbalance this mire, childish melodies —although somehow swapped for their evil doppelgänger— resonate with a sound of euphoria and loosening typical of the dopamine rush produced by opioids. It is all grimy and dirty, slow and muggy, dull and lifeless, just like a forced smile made by someone trying to persuade themselves that they are happy.

As if it were a litany, Future seems to be pulled from the darkness when he shows up to repeat “pour that bubbly“ before his voice breaks on the last repetition, sounding like a comatose fall into a marsh. “Drink that muddy“ follows, encouraging the possessed zombie to finish up his drink, while both the voice and the instrumental part evoke in concert a muddy feel.

Illustrating the song, its exceptional video directed by Uncle Leff lets us see Future’s hallucinating body devastated by remorse, addiction and depression. His inhabited body, like a corpse, lays down on a field and seems to be burning under a scorching sun as if the director wanted us to feel in our own bodies the addiction and its inevitable desire of self-destruction. The sedative color of the song does not mean however that it is not violent and the irruption of Future’s voice, obviously drugged (or pretending to be), is as uncomfortable as when an addict uncle shows up at his niece’s birthday party. Looking back at his life, the rapper appears to be remembering nothing but the worst, while his addiction makes him slowly slide into his grave. The listener is turned into a voyeur, uneasy in front of such a display of absolute nihilism.

If it does mimic the ravages of codeine’s recreational use on the body, “Codeine Crazy“ evokes as well the consequences that it has on a life, the gloomy syrup throwing the host it is inhabiting into a depressive and hardly escapable state. Everything in the writing echoes the excess and the wrongness in it, whether Future speeds up to gather as many different drugs as possible (“Smoke the kush up like a cigarette“, “pour a lil more liquor out“, “I'm sipping lean when I'm driving“) or develops how he treats the women he dates versus his spendings on expensive material wealth (“I just took a bitch to eat at Chipotle / Spent another 60 thousand on a Rollie“). Slowly, the topic moves like a mudslide towards a more sinister unease, when the rapper seems to be out of his depth in a bottomless well of dirty sprite: the drowning is guaranteed (“drowning in Actavis, suicide“). Along the same line, when the rapper refers to his breakup with the American singer Ciara, his diamond skin seems to be shredding to let show a sensitive soul (“I could never see a tear fallin’ / Water drippin’ off of me like a faucet“).

The last piece of the puzzle, “all this motherfucking money got me codeine crazy“, makes the song once again drift towards something else: the drug appears to be a shelter against the emptiness, the codeine being as much of an addiction as it is a substitute, a solace that brings its small weight of dopamine in a life where money did not bring any comfort and relaxation to a broken heart and soul.

While squeezing out of rap its most known and tired images, Future keeps claiming without convincing that he feels he is the best (“celebrating like the championship“), although his defying braggadocio does shine through his brilliant metaphorical ingenuity (“don’t tell me you celibate to the mula“). The acceleration of his delivery sounds every now and then as if he was back to life and yet the play never stops to crack as the songs keeps going, revealing his wounded soul lost in melancholy. Neither the diamonds nor the drugs can fill the void that is devouring him (and worse, they throw him into a more perverse and destructive state) and the rapper’s flows —between dopey whispers, agressive rapidity, lamentation overwhelmed with sobs and autotune singing that evokes a worn out and exhausted machine— draw a confusing and worrying whole.

In an interview with Shaheem Reid, Future once declared regarding his voice and its aesthetic possibilities given by its modification: “I used to listen to Pac sometimes. He didn’t use Autotune, but the way he said it with his aggressiveness, you know what I’m sayin’, you feel his words and I feel like Autotune makes you feel my words“.

And on “Codeine Crazy“ indeed, the tone and the work made on the rhythm of elocution reveal the melancholy behind the apparent energy like an opioid fury, a satanic tango that gives way to a shipwreck where the voice tears itself on the rocks and breaks out for the finale, once the storm is gone, with the last sentence: “I’m taking everything that comes with my children“.

Crafting a new sound for the dope boy blues, Future and TM88 describe addiction and the malaise that follows with words, vocal textures and sounds. “Codeine Crazy“ deploys a variety of illocutionary strategies in order to express better what’s at stakes, even if it means changing the rapper’s timbre so much that it dehumanizes it. That’s the paradox and the fascinating aesthetic of Future’s rap: in order to be as honest as possible, he needs to sound as distant as possible, as not human as it can be, which is what Autotune achieves here. It’s hard to know if his voice is modified from the codeine or if it is mimicking an attempt at finding new ways to express what’s in his soul but it is probably both. From dealer to user, Future bends the dope boy blues trope to paint the image of an addict drowning towards limbo, where any recreational use of drugs is beaten by the misery that comes and engulfs it in its gloomy shadow. It is no wonder A$AP Yams had rightly noticed the importance of this song, may he rest in peace.

0 notes