Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The time of the two-headed dragon

A long time ago, I played Dota 2 regularly. I first played Dota 2 in the beta, in June 2013, a few weeks before the official release in July. I played practice matches against bots as a variety of heroes, experimenting and learning the game. The day after the official release, July 10, 2013, I played my first actual match, against other human players. I played the hero called Jakiro.

Jakiro is an ungainly two-headed dragon that doesn't so much fly around the Dota arena as flop without ever hitting the ground. He doesn't have a particularly notable personality or cool cosmetics. When Netflix produced an animated series based on Dota about dragons, Jakiro didn't appear (according to internet sources, at least; I have no interest in watching it).

Jakiro is an awkward character both in appearance and in mechanics. Jakiro's abilities, at the time I first played him, were the following:

Dual Breath: An AOE that deals minor initial damage and applies a DOT and attack and movement speed slow to affected enemies.

Ice Path: A narrow line of ice forms in a straight line, extending a decent distance from Jakiro. Any enemy standing in the ice is damaged and stunned briefly.

Liquid Fire: Whenever Liquid Fire is off cooldown, Jakiro's next regular attack applies a DOT and an attack speed slow; then Liquid Fire goes on cooldown.

Macropyre: A narrow line of fire forms in a straight line, extending a decent distance from Jakiro. The fire persists for a while. Enemies take damage while standing in the fire.

The obvious power play with Jakiro was to combine Ice Path and Macropyre, using the Ice Path to stun enemies and force them to take damage from the Macropyre. Measured absolutely, both abilities cover quite a significant surface area, and deal a lot of damage. But Ice Path was slow enough to cast that enemies might simply move out of the way, and even if they didn't, both abilities are straight lines - their impressive surface area only matters if your enemies are literally lining up for you (or your team forces them to, you might think - but almost anything that force moves multiple enemies does so by pulling together into a bunch that would also make them easily targetable by normal, circular AOEs).

You couldn't control when Liquid Fire activated (other than by simply not attacking), so while it was a nice effect, it wasn't something you could really count on. Dual Breath was Jakiro's only particularly reliable ability, and its effect was definitely useful, but only in the accumulation alongside other abilities; it was never going to be flashy or feel particularly impactful.

Jakiro's abilities don't scale in the way that is needed for a hero to be played as a core role, so Jakiro more or less defaults to playing as a support. And on paper, Jakiro looks like a good support - nukes, slows, DOTs, a stun. Those are all effects that are signatures of strong support heroes. But again, the abilities were mostly rather difficult to use. A hero like Shadow Shaman had two different abilities that were functionally guaranteed stuns (barring immunities) - they were single target, sure, but hitting more than one enemy hero with an Ice Path as Jakiro was pretty uncommon anyway, and you had a reasonable chance of whiffing entirely.

So why did I choose Jakiro? I don't remember, honestly. But for some reason in those initial practice matches, I decided on the two-headed dragon, and, intimidated by the idea of learning more heroes, I stuck with him. Between July 2013 and January 2014 I played 44 games of Dota 2 (a little less than 2 games per week). 32 of those games were played as Jakiro. The ones that weren't were played in Single Draft or Random Draft modes in which the limited selection of heroes offered to me simply didn't include Jakiro. (In January 2014, Ability Draft released, a mode that became my mainstay for a few months and through which I finally learned other heroes, though Jakiro always remained my "default" hero when playing the standard mode.)

I would not say that I became a Jakiro "expert". I was never particularly good at Dota. But I did become comfortable and familiar with the hero to a degree that I imagine was very rare for other players of my skill level. Jakiro was not popular. Jakiro was never popular, at least in pubs - Jakiro had a brief window of popularity in the nascent professional scene during the early beta, but by 2013 he was also in the dumpster as far as the pros were concerned and would more or less remain there, with very brief and moderate exceptions, until this year.

I don't play Dota anymore, but I do still follow the professional scene, as I am fascinated by the game's mechanical complexity even if I cannot stand the community atmosphere that must be engaged with to at least some degree in order to play it (not to mention the innate stress of playing a team multiplayer game in which amateur matches often last over an hour).

Mechanically, Dota 2 has changed a lot over the years, and that includes Jakiro. Jakiro's abilities have been reworked (although none have been completely replaced, as many other heroes have had), and new abilities have been added. But the changes never really changed Jakiro's fortunes, as the fundamental awkwardness of the hero has been preserved.

An illustrative example: there's an item in Dota called the Aghanim's Scepter, which has a unique effect that is different for each hero, upgrading one of their abilities or adding an entirely new one. For some heroes, their Scepter upgrade is a core part of their heroes, a tax they must pay every game to unlock important abilities. For some other heroes, it's a gimmick.

For a significant period when I played Dota, Jakiro's Scepter upgrade nearly doubled the length of Macropyre. The easily avoided line of fire became a much longer, still easily avoided line of fire. For another period, Jakiro's Scepter upgrade was that the duration of Macropyre was significantly increased. Enemies continued to just walk around it. Both upgrades didn't even feel like gimmicks so much as jokes. (Though to be clear: the extra long Macropyre was a very funny joke.) Jakiros rarely had the gold to spend on an expensive item like Scepter, so it didn't really matter - but it still felt indicative of Jakiro's place in the game.

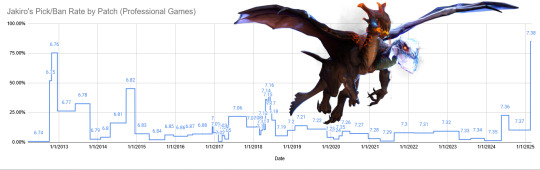

As I mentioned, Jakiro's fortunes have changed recently. A few months ago, I posted a chart on Bluesky. Here's an updated version with the statistics for all of professional Dota 2 up through patch 7.38:

The 7.38 patch ended last week (total duration: 93 days), so we have the final statistics for the patch now. Jakiro was the second most picked and banned hero across the patch (behind Tiny), either played or specifically removed from ~79% of all professional games. Looking at just picks, Jakiro was the number one hero of the patch, being played in nearly half of all professional games (~44%). The last time the most picked hero of a patch held a pick rate that high in a patch that lasted at least this long was nine years ago, in 2016, when Invoker held a 45% pick rate across the 180 days of patch 6.88.

There have obviously been a lot of pro Dota matches over the years, but given my viewing habits have been very intermittent, I can say that, personally speaking, it's not entirely implausible that I saw more Jakiro games in 7.38 than I saw in the entirety of pro Dota I'd watched before that point. For the first time since the game's beta (when there was a much smaller number of heroes to play anyway), Jakiro was everywhere.

I think it's important to convey that, because of the system of bans in professional games, Jakiro wasn't the best or second-best hero of the patch. The best heroes of a patch don't get played very much, because few teams are either brave or stupid enough to play against them; instead, they ban them. Jakiro was the 13th most banned hero of the patch - certainly indicative of being considered strong, but far from the best. Since there are only so many bans per match, hero drafting in professional Dota is a game of compromises: what are the least objectionable good heroes? So Jakiro wasn't the best hero of the patch. Instead, he was the best hero the most teams were willing to put up with. Which is, in its own way, just as impressive a title.

Of course, the wheel turns, and after less than a week of 7.39, Jakiro has once again fallen out of favor, collapsing down to a 15% pick/ban rate for the new patch so far. There's only a small sample size, admittedly, but I doubt that number will climb much. No hero gets to be ascendant forever, and Jakiro flew very, very high for the past few months.

Note: I pulled my own personal statistics mentioned early in this post from the Dota client itself, re-installing it for the first time in many years. The statistics regarding professional Dota in this post are thanks to datdota.com, an incredible resource for anyone interested in pro Dota. Any errors are mine.

0 notes

Text

On Megalopolis (2024) and the Catilinarian Conspiracy

I have watched Megalopolis (2024). My short review is: it is a bad movie, and not in a way that is worth watching. Spoilers follow, but again, I really don't recommend watching it anyway.

It is a surprisingly boring movie. Its plot is ultimately prosaic and uneventful in the macro, and basically nonexistent in the micro. That is to say: if I tried to explain the broad arc of the film's plot, it would seem childishly simple. But if I started explaining actual scene-to-scene events, it would often provoke questions of how those events relate to each other, in a basic causal sense, that I could not answer. This is a movie that is uninterested in laying a road for how it reaches its big points, and yet those points are also not interesting on their own.

It is also a very offensive movie. This is perhaps less surprising, except in how completely unmasked it is. I have not seen a movie with such open contempt for women in some time. This is a movie where, in the most straightforward and unquestioned way, the role of good women is to stand by and support great men, and women who stand outside that role in any way are unquestionably, indisputably evil. One of the two main villains is a lowborn woman who schemes to achieve wealth and power through seducing male betters; the other is an embodiment of gay/trans panic who is somehow also a Trump analogue.

The only things that I ultimately found interesting and worthwhile in the movie are:

The visuals. Sometimes the movie actually looks good. Mostly, however, it looks bizarre. Often it has that certain quality of something made with money that nonetheless looks bad, although it is at least generally visually interesting in a way that, to offer an incredibly low bar, Marvel movies do not.

The usage of Roman historical references/allegory is, quite frankly, absolutely wild.

It's this last point that had me most interested in the movie in the first place, and also the one I'd like to expand on.

What is Megalopolis?

If you're completely unaware of this movie, it is a kind of transported-historical-allegory (the movie terms itself a "fable") in which names, events, and cultural tropes from the late Roman Republic are applied to a modern New York City stand-in (simply called "New Rome").

The movie centers on Cesar Catilina (Adam Driver), an architect/wonder-scientist who maybe heads some kind of quasi-independent government department (again, the movie is very unclear about a lot of seemingly basic plot points) and is in a long standing feud with the city's mayor, Cicero (Giancarlo Esposito). On the sidelines of the feud are Crassus (Jon Voight), the richest man in the world and Catilina's uncle; Catilina's cousin/Crassus' grandson Clodius Pulcher (Shia LaBeouf), an ambitious, sexually ambiguous, crossdressing Nazi; and the lowborn journalist social climber absurdly named Wow Platinum (Aubrey Plaza, giving her all in a movie that does not deserve her). Much of the film is from the viewpoint of Cicero's daughter Julia (Nathalie Emmanuel), who gets involved with Catilina in order to investigate her father's claims about him, but Julia is less a character and more just a vessel for men to explain things to or have emotions about.

In the film, Catilina is a misunderstood, slandered genius and visionary; he was accused of murdering his wife and is at one point framed for having a sexual relationship with a teenager, both of which are conclusively proven false. The film positions him as a revolutionary being held back by the forces of "practicality" (despite being part of the richest family in the world and clearly wielding significant power on his own). He repeatedly and directly suggests that trying to do things to help people in real ways now is a threat to the continued existence of the human species, because what we need is vision, which comes from love, which can literally give you the power to alter the fabric of reality at will. (Why anything is an obstacle to Catilina when he has this literal godlike superpower is also something the movie is uninterested in answering.)

Catilina does have the first name "Cesar" (pronounced just like "Caesar" in English), and you can certainly try to draw out some weak parallels between Caesar the dictator and Catilina (ties to Crassus, opposition from Cicero, antagonism with Clodius Pulcher). The character's parallels with the historical Catilina (generally called "Catiline" in English) are... about as weak. But I assume most people are familiar at least with the basic arc of Caesar, while most people will not be familiar with Catiline, who is a much funnier figure to pull for this sort of allegory, so I want to explain. (To be clear, I'm not a historian, but this is a period I do find fascinating.)

Very briefly, on the decline of the Roman Republic

The decline and collapse of the Roman Republic (which was, to be clear, a state whose government and economy were from the beginning built around conquest and slavery) was a slow process that occurred over generations. While the first big signs of structural danger might be traced back to the Gracchi (active roughly 133-121 BC), the civil wars that eventually broke the Republic can be very roughly grouped into three generations: that of Sulla and Marius (roughly 91-73 BC), Caesar (roughly 49-44 BC), and Octavian (roughly 43-30 BC).

Of those, Sulla is probably the figure least commonly known, but he's very important. Following the Social War (an uprising of Rome's vassals which functionally ended in Rome's defeat), Sulla led the first fully Roman army to march on Rome, revived the long dormant office of the dictatorship (having himself appointed by force), killed and seized the wealth of many of his enemies (and random others), made radical changes to Rome's government and legal system in order to to achieve his political goals, then left for the countryside.

Sulla's example served Caesar (a young man at the time of Sulla's rule) as both precedent and lesson to learn from; it seems clear that many of Caesar's decisions were influenced by trying to achieve a more lasting result than Sulla (many of whose political changes were discarded almost immediately after his death). Many of the famous figures of Caesar's time, such as Pompey and Crassus, also cut their teeth in Sulla's wars.

Shortly after the final end of Sulla's wars (which outlived Sulla himself), about twenty years before Caesar's march on Italy, there was another major civil conflict - the mass slave revolt whose leaders included an escaped gladiator known as Spartacus, ultimately put down by armies commanded by, among others, Pompey and Crassus. In the relatively peaceful (within Italy) years after that, the slightly younger Cicero worked his way up from comparatively humbler beginnings (working as, basically, a lawyer/speechwriter for hire), as did (the much higher-born) Caesar.

Who was Catiline?

You'll notice I haven't mentioned Catiline yet. That's because Catiline isn't really relevant to any of this history. He was born into a noble family and did become wealthy by siding with Sulla in his wars, but were it not for the one thing Catiline became famous for later, he would be simply one of several dozen Roman elites who were within a small enough circle of wealth and power to be relatively well documented even millennia later but who just aren't really important when narrativizing the history.

So what is Catiline famous for? In the 60s BC, Catiline, born into nobility, wealthy from spoils of civil war, and with powerful political allies, reached the second highest position in the Roman government (praetor). He served multiple terms, including as a provincial governor, and despite being tried multiple times for corruption and other crimes, he was never convicted. But like any good Roman elite, that wasn't good enough - Catiline wanted to have his turn at the top, as consul.

Positions like consul and praetor were elected (though buying votes was more or less legal and common). Catiline ran for consul multiple times, and lost each time. The last time, one of his victorious opponents (there were two consuls at any one time) was the "self-made man" Cicero. With Catiline's wealth spent on the failed election campaigns, his political allies deserted him. Catiline apparently felt he deserved more.

It's hard to be confident of exactly how much direct agency Catiline had in what followed, given that our sources are largely rooted in Cicero's representation of the events, and Cicero quite happily used Catiline as a political prop for his own self-promotion. But here's what we're told:

News came to Rome of a ragtag army led by a minor officer that was plotting to march on Rome to overturn the election and install Catiline.

A series of fires were set in Rome, ostensibly by conspirators to disrupt the city in advance of the army's approach.

Assassins were sent to kill Cicero, a man never known for any military or physical prowess. He escaped and reached the Senate.

Cicero denounced Catiline in the Senate and demanded his arrest; Catiline denied any involvement in the events but fled the city and met up with the ragtag army.

An army led by the other consul departed Rome to pursue Catiline's army.

Meanwhile, envoys of a Gallic tribe on Rome's northwestern border reported to the Senate that Catiline's supporters had tried to get their support in exchange for concessions from Rome upon Catiline's success. They handed over written, signed documents to Cicero, who promptly arrested those named.

Cicero, in one of his rare moments of decisive action, had the detained conspirators executed without trial. Despite being consul at the time and acting with the Senate's approval, the threat of prosecution for these extrajudicial killings hung over his head for the rest of his life.

As the consular army approached, Catiline's army largely abandoned him.

Catiline and his remaining supporters tried to escape north to Gaul, but were cut off. The consular army forced an engagement and annihilated Catiline's small force. Catiline was killed in the battle.

The whole series of events played out over the course of a few months, and its most lasting political legacy seems to have been giving Cicero credit as a man capable of doing violence in defense of the state, a vital attribute for Roman elites (where all high-ranking officials were also generals and vice versa) that he otherwise mostly lacked.

In a decades-long period dotted by large scale civil wars that repeatedly, radically altered the Roman state, Catiline's conspiracy is an also-ran. It's possible (though it seems unlikely) that Catiline harbored some laudable ambitions toward reform (as he is alleged to have made overtures to the poor in an attempt to build support), but even if so, in execution his conspiracy seems to have started poorly and only gotten worse. He didn't even get far enough to be the farce to Sulla's tragedy; he has become, often literally, a footnote.

So why Catiline?

When I saw the first trailers for Megalopolis, I was baffled as to why anyone would thus choose Catiline, of all people, to center as a heroic figure in a Roman-inspired history. In the full film, the villainous Clodius Pulcher riles a mob and builds a political movement (that uses explicit Nazis symbols) on the back of superficially populist rhetoric and his family wealth toward the aim of seizing power over both Cicero and Catilina - a plot that sounds a lot more like the historical Catiline.

(What's the historical Pulcher famous for? Mostly some bizarre incidents that presumably inspired the crossdressing featured in the film, but also for a feud with Cicero that culminated in him successfully if temporarily exiling Cicero from Rome for those extrajudicial murders during the Catilinarian conspiracy!)

For a while, it seems like the film is heading towards Cicero failing to stop Pulcher's fascist takeover due to his preoccupation with obstructing Catalina - which would at least be something. But instead, Pulcher is first manipulated and made the puppet of the real villain, a woman who doesn't know her place, and both are ultimately defeated by the lecherous, senile, and literally bedridden Crassus, who then instead bequeaths all his assets to Catilina, which allows Catilina to finally complete the titular Megalopolis, a utopian Tomorrowland in New Rome's Central Park which will apparently save the world by giving a handful of presumably very rich people a walkable green micro-city to live in.

So again, the movie is bad, but I still would like to know: why the fuck is it Catiline? There is literally no conspiracy or coup attempt in the film except by Pulcher. Catiline doesn't really do anything except mope about a dead wife, sleep with a female employee probably two decades his junior, and say lines destined for the "written for a smart character by a dumb person" hall of fame. (Seriously there are multiple montages, intended to show him working on Megalopolis, that are just this, over and over, and they're some of the few parts of the movie that are entertainingly rather than boringly bad.) Seemingly the only thing from Catiline's life that crosses over to Catalina's is "he and Cicero didn't like each other". I suspect this will continue to bug me.

1 note

·

View note

Text

A brief summary of each season of The CW's "The 100" (2014-2020)

This is all 100% factual. You can also add "also there's a lot of politicking and in-fighting and betrayals and straight up murder" to every one of these.

Season 1: It's Fallout, but with teens! 100 years after a nuclear war has destroyed the world, 100 teen criminals (plus one stowaway) are sent from a Vault space station to near the ruins of Washington, D.C., to determine if the surface is survivable. The 100 (plus 1) immediately encounter tribals "Grounders", people living on the surface with limited technology and social organization, and become embroiled in violent conflict. At the end of the season, the space station's surviving population comes to Earth, while the teens kill dozens of Grounders in a battle.

Season 2: Most of the surviving 100 are kidnapped by the Enclave people living in the continuity-of-government bunker at Mount Weather. The space station's population make a fragile peace with the Grounders to fight Mount Weather, who regularly kidnap Grounders for experimentation. A faction inside Mount Weather objects to the treatment of the people from space because they're not primitives and begins helping the prisoners. The alliance almost succeeds, but Mount Weather's leader makes a deal with the Grounders to release their prisoners only. Unable to overcome Mount Weather's soldiers, two teen heroes unleash radiation on the facility, killing everyone not a Grounder or from space¹, including those helping the prisoners.

Season 3: More survivors from space show up and convince most of the space people that they should declare war on the tens of thousands of Grounders and begin with massacring a small Grounder army pledged to protect the space people. Fortunately a new threat forces the Grounders and space people to team up again: a rogue AI that caused the original nuclear war and has now created a mind controlling cult as well as a digital afterlife. The only way to defeat a bad AI is with a good AI, which happens to be what's actually on an artifact implanted in the head of every Grounder leader, along with a digital replica of all previous leaders' consciousnesses. One teen hero takes the good AI and bad AI (and the consciousness of the previous Grounder leader, her dead ex-girlfriend) into her head so that the former can kill the latter.

Season 4: The bad AI revealed that the reason for attempting to mind control all remaining humans is because "after the second Fukushima disaster", nuclear power plants were required to have automated systems that could run for 100 years without human intervention. Those plants have now undergone meltdowns, which has created a "Death Wave" of fire hundreds of meters tall that is slowly moving across the entire planet, followed by heightened radiation levels that will last for 5 years. Those in the know seek various solutions to surviving the Death Wave, with the majority of survivors ultimately doing so in a massive bunker under the Grounder capital built by a tech billionaire turned escape room designer/cult leader before the nuclear war. One teen hero who has been very, very depressed for two seasons since the massacre at Mount Weather leads a group of space people in killing themselves instead.

Season 5: 6 years after the Death Wave, one teen hero and her new adopted daughter, who have both been able to live on the surface thanks to Nightblood², discover a spaceship landing on the literally one spot on Earth that still has plants growing. The spaceship is crewed by convicts who were put into cryogenic stasis and sent into deep space to do mining, but mutinied at their destination and have now returned to Earth after more cryo-sleep. A group of teen heroes who survived the 6 years on the remains of the original space station make a temporary deal with the convicts to open the sealed bunker, which has come to be led by one of the teen heroes as the "Blood Queen", who now oversees regular executions via gladiatorial combat and who also forced everyone to embrace cannibalism for a while. The bunker's population fights a war with the convicts that leads to the destruction of the last remaining living ecosystems on Earth.

Season 6: The survivors of the space people, the convicts, and the Grounders use the convicts' spaceship to travel for 100 years in cryo-sleep to another planet that, prior to the nuclear war, once had a spaceship sent to it to attempt colonization. They discover a human society in which members of the original colonization team have become gods who use "mind drives" to preserve their consciousness and repeatedly resurrect via implanting themselves into new bodies (killing the consciousness of their original inhabitants). Also, regular eclipses on the planet release a toxin that makes everyone go comic book crazy and hallucinate dead people for character development. Also, there's a giant green energy whirlwind referred to as "The Anomaly" that causes regular "temporal storms" that are basically timefall from Death Stranding. Also, an AI construct of a previous Grounder leader called "the Dark Commander" possesses the teen hero's adopted daughter; freeing her requires the good AI to be destroyed. That teen hero kills most of the self-proclaimed gods, while the pregnant leader of the convicts and the former Blood Queen disappear into the Anomaly.

Season 7: The Anomaly turns out to be a wormhole that is controlled by a hidden Stargate orb device. 200 years ago, just after the nuclear war, the tech billionaire turned cult leader turned on an orb device he stole from Peru and took his cult to another planet (not the one from the previous season). The cult leader discovered a dead alien civilization and texts that promised a "Last War" accessible through the orb that would lead to either all humans becoming Q Ascended glowing yellow energy balls or being exterminated; he promptly set his cult to prepare for this war (and then went into cryo-sleep so he can be alive in the present day). The cult also maintains a prison planet near a black hole where time moves much faster. The leader of the convicts gives birth on the prison planet, and that baby is now a teen when they meet up with everyone else. The Dark Commander's AI construct possesses the last self-proclaimed god and briefly takes over the planet from season 6. The "Last War" turns out to be an oral exam given in Heaven to a single individual by an omnipotent alien. The cult leader starts the exam but is murdered in Heaven by a teen hero partway through; the alien fails humans and prepares to exterminate the entire species until another teen hero convinces them that trust us bro, we'll be good, and they're all turned into glowing yellow energy balls except for the teen hero who murdered the cult leader (as punishment for murdering someone in Heaven). The surviving teen heroes, the adopted daughter, the black hole baby that's now a teen, and their significant others decide to retake human forms and live together, but are told they will not be able to have children or become glowing yellow energy balls again.

The Grounder background gives Radiation Resistance +5. The Space background gives Radiation Resistance +10.

The Nightblood perk gives Radiation Resistance +20 and the ability to host AIs in your head without dying immediately.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Shadow of the Erdtree thoughts

[Originally posted on Cohost 25/8/24. Edited for formatting because tumblr apparently refuses to allow nested lists in any fashion.]

I finally finished SOTE yesterday. Putting these thoughts in a post for linkage elsewhere. Spoilers obviously.

First:

I think base game Elden Ring is beautiful, and I think the DLC is as well. I really enjoyed how the DLC immediately pushes into new palettes and biomes that weren't seen in the base game - from the starting prairie area (how rare to say "I like their use of brown" but it really does work for me) to some of the much more outlandish later areas. I feel like the day-night transitions also have a lot more color shifts in the sky that look really great.

Second:

I found the DLC narratively disappointing. I liked the NPCs (and was fortunate enough to not break any of them outside of some minor stuff with Thiollier and Moore) and I liked the concept of the hornsent and their relationship with Marika, but the actual Miquella plot is a real letdown to me.

These games (Demon Souls/Dark Souls/Bloodborne/base Elden Ring) are obviously associated with ambiguity (though I think sometimes that is overblown, e.g. in the first Dark Souls), but after finishing this DLC, looking up stuff I missed, and reading some other people's comments, I genuinely do not know what Miquella needs from the Land of Shadow, what the connection is between Messmer's position in the Land of Shadow and Miquella's goals, or what the player's role in the Land of Shadow is. This is literally the central plot of the DLC, and I feel like I should not be in the dark about it. It kind of seems like Miquella just needs to walk through a hole in some rocks (a hole we are prevented from walking through not by some message about being unfit for godhood, but by a 5 foot rise of rock), which seems very silly.

I hated the suggestion some people made from the base game that Miquella charmed Mohg into kidnapping him, and I hate that it is directly brought up here. I would like to read this as denial on Ansbach's part, but I feel like the game leans pretty strongly toward this being true. (It also doesn't really make sense to me within the world of the fiction, because if Miquella can charm Mohg, why can't he just charm Radahn in the first place? If Miquella can charm demigods, why is there even any civil war among them at all? Can't Miquella just win automatically?)

I don't mind many of the things left confusing or ambiguous in the base game being unaddressed here (I would still very much like anything at all pointing me toward a specific interpretation of what Radagon actually is, but I understand that isn't directly relevant to this DLC), but the almost total lack of reference to the Albinaurics is pretty disappointing to me. So much of the story of Miquella in the base game centers on the Albinaurics' faith in him, and the absence of any elaboration one way or the other on that seems very odd.

Radahn's reappearance, while not entirely out of the blue, does strike me as strange and unsatisfying. I didn't expect to fight Miquella directly, so that's not my issue here; but Radahn feels like a rerun, not just of himself and Mohg but also of Dark Souls 3's Twin Princes. Part of this is certainly bound up with my opinions on the final boss as a gameplay experience (see below), but I also think, trying to set the actual fight aside, there's nothing interesting done with bringing Radahn back. I saw someone postulating an alternative final boss with Miquella resurrecting Godwyn's spirit in Mohg's body instead, and while obviously my imagination has less constraints than game development, I found that idea immediately more compelling in its storytelling potential than Radahn.

Third:

On the whole, I enjoyed the big setpiece fights of this DLC, with one extremely glaring (and unsurprising, given the reception I've now been reading) exception.

Bosses I liked:

Rellana is a fun reprise of some visuals I've really enjoyed before - I am one of those people who loves Artorias, Pontiff Sulyvahn, and Dancer of the Boreal Valley.

The Divine Beasts are incredible fights to look at. I feel like they would be a nightmare to actually parse as fights in melee, but fortunately I wasn't trying to do that.

Bayle is a great new dragon fight (although the other dragon fights, like those in the base game outside of Fortissax and Placidusax, feel too repetitive).

The Scadutree Avatar is a great new giant monster fight.

Leda & co. is the only good version of this kind of fight From has ever done. I really like Dryleaf Dane.

Bosses that didn't make much of an impression on my positively or negatively:

Messmer, Romina, Metyr, Putrescent Knight. I do appreciate Romina for finally giving us a version of Scarlet Aeonia that is regularly usable though - I used it for basically all the bosses afterward, including many of the final base game bosses as I finished my replay.

The boss I thought absolutely sucked:

Radahn.

On top of being narratively uninteresting, as I mentioned above, the fight feels like a remix of stuff we've seen before that doesn't evoke anything new from their combination. The only really unique part of the boss fight, I think, is Miquella's grab, which is a neat gimmick but not enough to overcome how much of a slog the fight is.

I think the most infuriating thing to me is that it feels straight up worse to bring in the story NPCs for the fight - your reward for having completed their quest lines and brought them to this climatic fight is that the fight gets much longer and harder (because they don't contribute damage to match the boss's increased EHP). It's a bizarre choice to me when in this very DLC there are multiple bosses that let you summon NPCs into them without affecting the boss, because the game wants you to use them! But here it feels like you are punished for doing so. (I must admit I also made this harder on myself because my replay character was a gimmick build centered on applying buffs and debuffs, using spirit ashes and NPC summons to do much of the damage.)

The boss is also one of those, common in these later games and especially their DLCs, that does extremely long combos of attacks with few and small opportunities to counter attack, which I find to be an uninteresting challenge.

Overall:

I enjoyed most of my time with this DLC, because I like playing Elden Ring. I had had a desire to replay Elden Ring repeatedly since I first completed it and largely held off, because the base game is so damn big and I could not justify it to myself over doing many other things with my time. I said I would allow myself to do so when the DLC came out, and I did that (starting a few weeks before the actual DLC release, so I would be ready to go in when it dropped).

The base game is still largely good, and as I said, I really enjoyed exploring the new regions of the DLC just to see the beautiful, weird landscapes and the freaks that they were populated with. But having completed it, I feel very mixed about it; without a satisfying narrative to tie it all together - or even just an unsatisfying but compellingly confusing collection of narrative pieces to chew on and ponder, which is how I mostly feel about the base game - Shadow of the Erdtree ultimately feels like less than the sum of its parts.

ETA: Shoutouts to Jolan and Anna, who carried my spirit-focused build in the endgame when my Greatshield Lads were finally no longer able to do the job.

2 notes

·

View notes