A blog about chocolate for a college class.

Last active 2 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

WORKS CITED:

Chocolate in the Underworld Space of Death: Cacao Seeds from an Early Classic Mortuary Cave (Keith M. Prufer and William Jeffrey Hurst) Chocolate: Cultivation and Culture in pre-Hispanic Mexico Author(s): Margarita de Orellana, Richard Moszka, Timothy Adès, Valentine Tibère, J.M. Hoppan, Philippe Nondedeo, Nezahualcóyotl, Nikita Harwich, Nisao Ogata, Quentin Pope, Fray Toribio de Benavente, Motolinía, Guadalupe M. Santamaría and Daniel Schechter Source: Artes de México, No. 103, CHOCOLATE: CULTIVO Y CULTURA DEL MÉXICO ANTIGUO (SEPTIEMBRE 2011), pp. 65-80 The Power of Chocolate Author(s): Blake Edgar Source: Archaeology, Vol. 63, No. 6 (November/December 2010), pp. 20-25 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Tasting Empire: Chocolate and the European Internalization of Mesoamerican Aesthetics by MARCY NORTON CHOCOLATE II: Mysticism and Cultural Blends Author(s): Margarita de Orellana, Quentin Pope, Sonia Corcuera Mancera, José Luis Trueba Lara, Jana Schroeder, Laura Esquivel, Jill Derais, Mario Humberto Ruz, Clara Marín, Miguel León-Portilla, Michelle Suderman, Marta Turok, Mario M. Aliphat Fernández, Laura Caso Barrera, Sophie D. Coe, Michael D. Coe and Pedro Pitarch Source: Artes de México, No. 105, CHOCOLATE II: Mística y Mestizaje (marzo 2012), pp. 73- 96 The Introduction of Chocolate into England: Retailers, Researchers, and Consumers, 1640- 1730 Author(s): Kate Loveman Source: Journal of Social History, Vol. 47, No. 1 (Fall 2013), pp. 27-46 Published by: Oxford University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43306044 Encomienda, African Slavery, and Agriculture in Seventeenth-Century Caracas Author(s): Robert J. Ferry Source: The Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 61, No. 4 (Nov., 1981), pp. 609-635 Published by: Duke University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2514606 Accessed: 12-07-2019 16:34 UTC The Cacao Economy of the Eighteenth-Century Province of Caracas and the Spanish Cacao Market Author(s): Eugenio Pinero Source: The Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 68, No. 1 (Feb., 1988), pp. 75-100 Published by: Duke University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2516221 Accessed: 12-07-2019 17:03 UTC Establishing Cacao Plantation Culture in the Western World - Timothy Walker The Ghirardelli Story Author(s): Sidney Lawrence Source: California History, Vol. 81, No. 2 (2002), pp. 90-115 Published by: University of California Press in association with the California Historical Society Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25177676 The Evolution of Chocolate Manufacturing Rodney Snyder, Bradley Foliart Olsen, and Laura Pallas Brindle The Emperors of Chocolate - Inside the Secret World of Hershey and Mars by Joel Glenn Brenner (Random House, 1998) Bitter Chocolate by Carol Off (The New Press, 2006) "Cocoa's child labrorers", Whoriskey, Peter; Siegel, Rachel, The Washington Post, June 10 2019 The Harkin-Engel Protocol (Chocolate Manufacturers' Association, 2001) "Role of Trade Cards in Marketing Chocolate during the Late 19th Century", Virginia Westbrook "Chocolate at the World's Fairs, 1851-1964", Nicholas Westbrook Edible Ideologies by Kathleen LeBesco (SUNY 2008) Cosmopolitan cocoa farmers: refashioning Africa in Divine Chocolate advertisements Author(s): Kristy Leissle Source: Journal of African Cultural Studies, Vol. 24, No. 2 (December 2012), pp. 121-139 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42005280 Chocolate Nations: Living and Dying for Cocoa in West Africa by Orla Ryan (Zed Books, 2011) Cocoa by Kristy Leissle (Polity, 2018) How Mars Inc., maker of M&Ms, vowed to make its chocolate green. And failed. Mufson, Steven . The Washington Post (Online) , Washington, D.C.: WP Company LLC d/b/a The Washington Post. Oct 29, 2019.

0 notes

Text

Part 9: Yes, Really, A Chocolate Potato Cake.

Pictured above: the cake in question. This recipe was first published in 1912, but was made famous by YouTuber and TikToker B. Dylan Hollis. He specializes in making weird recipes from 20th century cookbooks. It was actually delicious! Now, I chose this recipe for many reasons. One, I'm Irish. Two, the history of potato cultivation was actually kinda similar to that of chocolate cultivation. Both were native to the Americas, both were staple crops of a vast and mighty empire (the Maya and Mexica in the case of chocolate, the Inca in the case of the potato), both were taken to Europe by the Spanish, both are now associated more with European countries than with the Americas (Switzerland, the Low Countries and England for chocolate, Ireland and most of Eastern Europe for potatoes). Three, both have surprisingly dark histories. As someone of Irish descent, I grew up on stories on the Great Famine. In the first half of the 19th century, when Ireland was still part of the UK, Irish farmers began growing potatoes as a way to supplement their income...but they began to depend too much on it, and more specifically a single variety of potato. It was the only food they could afford to grow...and for many Irish, the only food they could afford period. After an outbreak of potato blight hit Europe, Ireland was hit the hardest, leading to the Great Famine and to one million Irish people leaving for greener pastures. And I've already went over the dirty history of the chocolate industry.

Combined together, they represent the products of oppressed peoples, of diaspora, of shared hardships. But also camaraderie. I offer this chocolate potato cake in hopes of a better, more peaceful world.

--CAKE-- 1/2 cup salted butter 1 cup sugar 2 eggs 1/2 cup whole milk 1/2 cup riced/mashed russet potato 1 cup flour 2 teaspoons baking powder 1/2 teaspoon each of: cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg 1/2 cup GRATED semi-sweet chocolate (2oz, or half a baking-chocolate bar) 1/2 cup chopped nuts (I recommend walnuts) -- FROSTING -- 2 tablespoons salted butter 1 cup sugar 1/4 cup whole milk 2 oz semi sweet chocolate 1/2 teaspoon vanilla extract

Instructions | CAKE: 1.) Set diced potato to a boil until tender. I do not peel the potato. 2.) Cream together butter & sugar until fluffy and pale. 3.) Slowly incorporate the eggs, which have been beaten. 4.) Rice or mash potato in a separate bowl, then stir and cool with milk. 5.) Incorporate the potato & milk, mixing well. 6.) Combine flour, leavening & spices in a separate bowl. 7.) Gently incorporate the flour mixture, grated chocolate & nuts. 8.) Add batter to a buttered and floured 8x8 inch cake tin. 9.) Bake at 350 fahrenheit for 45-55 minutes.

Check at 40 minutes with a toothpick.

When inserted into centre then pulls away clean - the cake is done.

Instructions | FROSTING: 1.) Add all ingredients; save for vanilla, to a saucepan. 2.) Set to a LOW boil for 15 minutes, stirring occasionally at first. Remove from heat. 3.) Add vanilla, and beat to desired consistency. 4.) Apply frosting to the cooled cake.

Beating more will lead to a spreadable frosting - less so will lead to a thick, pourable glaze which will set wonderfully once cool.

Briefly chilling the boiled frosting will help to thicken, just stir before application.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part 8: Sustainability, Fair Trade, and Consumer Rights

Pictured above: Children in Montreal, Quebec, Canada on strike over a price hike in chocolate bars, 1947. The chocolate bar strike was a major cause celebre in the country before the chocolate manufacturers ran smear campaigns accusing the children of being Communist agents. This really happened.

Now, the only thing these big corporations understand is money. So how about we exercise our rights as consumers and not give them our money? We already made them take poisons out of their products that way.

One of the big trends in artisanal consumer products is fair trade. That is to say, actually paying the people who grow your stuff. Wow, what a concept! But for real, it's kind of messed up how Africa produces the majority of the world's chocolate but only consumes less than five percent of the world's chocolate. While this usually means a higher price for the consumer, it also means that the producers get paid fairly compared to standard trade practices. One of the biggest companies specializing in fair trade chocolate is the Dutch company Tony's Chocolonely, founded by a former TV journalist who had investigated child slavery in African chocolate production. I remember fair trade being a big buzzword in the 2000's: the punk band Rise Against did a music video promoting the concept for their song "Prayer of the Refugee", where they tear up a supermarket.

youtube

But there's another, bigger problem ahead: chocolate production leads to a lot of deforestation, and sometimes chocolate farms actually break into protected forest areas to grow their product. And with climate change, it's getting harder and harder to grow chocolate. Some companies have opted to create a more sustainable way of harvesting chocolate, to...let's say mixed results. See, there's thousands of cocoa farms, mostly small plots of land. And it's hard to keep track of all of them even if you are a really big company like Nestle or Hershey. Also, lots of people are susceptible to bribery there. So what is the future of chocolate consumption? Consumers alone can't fix it. Companies alone can't fix it. Governments haven't taken action, and even if they do the companies usually ignore it. So what are we supposed to do? It seems like these contradictions are inherent to the capitalist system...and perhaps, we shouldn't just rethink how chocolate is made, but how all commodities are made, and how the people who make them are alienated from the products of their labor...

Now I'm not suggesting we support a cultural revolution under Maoist-Third Worldist theory...I'm just saying that we should keep the option on the table.

(Up next: a chocolate potato cake recipe! No, for real)

0 notes

Text

Part 7: Now It's Sexist And Racist!

youtube

Seen above: the infamous Cadbury ad with a gorilla playing the drum part to Phil Collins' "In The Air Tonight". Does it make sense? No. Is it awesome? Yes. It is a good palate cleanser for the horrors of the last few posts and the probable horrors of what we're about to see next? Also yes.

I remember reading somewhere that eighty-two percent of all new consumer products released per year will be off the market within the next one or two years. The 18% that make it? They have good publicity.

Ads are time capsules of the past, and you can tell a lot about the culture of a certain time period by its advertising. Just look at the post-war era: 50's ads were about convenience and technology, 60's ads were about being cool and hip, 70's ads were earth tones and disco, 80's ads tried to be sophisticated, 90's ads tried to be EXTREME, 2000's ads tried to be staid, and 2010's ads just tried way too hard to be funny.

Chocolate is no different. Here's a few historical time capsules:

"HER" day. "HER" family. "HER" chocolates. Remember in Part 3, where I talked about how women in colonial Mexico would give enchanted chocolate to men that they wanted to hook up with so that they would fall in love with them? A few centuries after that, the genders seemed to have been reversed. Chocolate was something men would give to girls. It was a female-coded foodstuff. So of course, we had to make chocolate for MEN.

Chocolate is a FIGHTING food. Eaten by SOLDIERS. From ARMY. Who are STRONG and AMERICAN. Like NESTLE. A company from Switzerland that also makes baby food.

I love how they're selling it like it's a protein bar. This would like, completely ruin your gains if you ate it after you worked out. Nothing's changed much, considering that they're now hiring sexy models to make chocolate look sexy. Okay, wanna see something really fucked up? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YKFDfLqMoWw

There's an amazing book by Vincent Woodward about the slave trade called The Delectable Negro (awkward title, I know) where he argues that the slave trade was actually a form of cannibalism. Woodward died before the book was published, but I wish he was still alive just so I could ask him if he had seen this.

Hey, remember when everybody thought the world was gonna end on December 21, 2012 because the Maya said so?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B7M_cpovLX8

After seeing this, I wish the world did end. On the next post: the future of chocolate, and the light at the end of the tunnel.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Part 6: Oh God, Even More Slavery, This Time With Children.

Pictured above: photo of anonymous child laborer in African chocolate farm.

Sometimes I feel like us first-worlders need to enjoy our worries more often. Because most of the time, the things we worry about are a privilege.

Every now and again, everyone eats a piece of chocolate that makes them feel guilty about eating it. "Oh, I shouldn't have had that last Kit-Kat, now I feel too fat!" That's a worry that only privileged people can have. For the people who picked the cacao for that Kit-Kat, they're worried if they're ever gonna get off the literal child slave camp they've lived their whole life on.

As mentioned before, the modern story of African chocolate begins in the islands of Sao Tome and Principe, which at the beginning of the 20th century was Portuguese colony located off the coast of Nigeria and Cameroon. Nicknamed "the Chocolate Islands", the soil and location made it very good for chocolate production.

And slavery. Now, as mentioned before, it technically wasn't slavery. Under the "servicais" system, the laborers on the plantation in Sao Tome and Principe (who mostly came from neighboring West African colonies) came of their own free will...but they were supposed to live on the island for five years, as specified by a contract. Oh, and they have to work 9 hours all days (except for Sundays or Fridays, depending on the worker's religion). And 3/5ths of the money goes to the employer. It was a system rife with abuse. One of the largest purchasers of cacao from Sao Tome and Principe was Cadbury. Cadbury were all about charity and Christian ethics. The Cadbury family were Quakers, a church with a strong tradition of social justice and anti-racism. So what did they do when they found out about all the abuses on their farms? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GB7mHxdHlRY

Yes. Nothing. They just let it slide. This set a dangerous precedent. For a century afterwards, as African countries gained independence and multinational corporations replaced colonial empires, the problem of forced labor in the production of cacao was ignored. At the dawn of the new millenium, two members of the United States Congress--Senator Tom Harkin of Iowa and representative Eliot Engel of New York--tried to stop it. They tried to pass a bill for the FDA to mandate a label for chocolate bars sold in the US to have a "slave-free" label if the producer did not use child slaves in growing the beans (much like the regulations around dolphin-safe tuna), but the chocolate producers spent millions against it. Undeterred, the two politicians created the Harkin-Engel Protocol with the chocolate companies, hoping for the chocolate companies to clean up their own backyards and deal with the problem themselves.

And as always, they mostly did nothing while insisting that the problem was gone.

I hate the world sometimes. Next post, we will go away from the harrowing world of child slavery into the harrowing world of marketing!

0 notes

Text

Part 5: The Industrial Revolution and Chocolate

Pictured above: a postcard of Cadbury's Bournville Works factory in Birmmingham, England. Bournville was a model village created by Cadbury to house the company's employees.

The industrial revolution, and its consequences, have been a disaster for the human race a boon to chocolate production. Modern cocoa powder was created by Dutch chocolate maker Coenraad Johannes van Houten, who discovered that a hydraulic press could be used to remove the fat from cocoa beans. To this day, the process is called "the Dutch process".

Meanwhile, in England, new chocolate companies run by families began springing up to produce chocolate. Many of these families were Quakers, and they went into the chocolate business because of religious persecution and to promote a healthy alternative to alcoholic beverages. The largest of these was Cadbury, which even built a model town to house their factory workers. The company had a strong charitable ethic, and an emphasis on family values. In Switzerland, Nestle popularized milk chocolate, claiming to provide a more nutritious chocolate bar. One of the oldest chocolate companies in the United States, Ghiradelli, was founded in San Francisco in 1852 by the Italian chocolatier Domenico Ghiradelli. Ghiradelli remains America's best-known "luxury" chocolate brand, with a quality over quantity approach and a European flair. But it's hard to talk about American chocolate without talking about Milton Hershey. The Pennsylvania Mennonite created America's largest chocolate company, created a town to house his workers (and a theme park!), and was the official chocolate maker of the US Army for decades. He was a pioneer in marketing, to the point where if he found a wrapper for a Hershey bar in the street, he would put it right-side up so the label would show. Debate the quality of his oddly cheese-tasting chocolate all you want, but the man was a pioneer.

Around this time, production of the actual bean moved from Latin America to West Africa, with the Portuguese colonies of Sao Tome and Principe becoming the first chocolate producing nations in Africa. Most of the slaves who worked on Latin American chocolate plantation were of West African origin...weird coincidence, since the chocolate companies turned a blind eye to slavery in their chocolate farms. Well, okay, technically it wasn't slavery, they were indentured servants...but most of them didn't come home anyways. Jesus Christ, chocolate industry, can you STOP with the slavery for just five seconds?

The answer is...no.

0 notes

Text

Part 4: Colonial Production (This Is The First One With Slavery)

Pictured above: a painting of black slaves on a sugar plantation.

It's a universal constant. Rich countries want a lot of something that can only be found in poor countries, so they exploit the poor countries and barely give that something to them.

Speaking of, here's a piece of pop culture trivia: Did you know that, in the first edition of Roald Dahl's Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, the Oompa-Loompas were all African pygmys?

Hey, I never specified this had to be a FUN fact, right? Slavery and chocolate have always gone hand in hand. In the early days of Spanish colonization, there was the "economienda" system, where Natives lived as feudal peasants and produced chocolate and sugar for export. And no, they did not get any for themselves. Good on you for catching that!

As time went on, more and more Natives began dying out, and African slaves were brought in to work the plantations. Chattel slavery was one of the worst crimes of colonialism, and it has a part in the history of chocolate as big as it does in the history of cotton, or tobacco, or sugarcane. Soon, entire colonies were built on chocolate production: the modern day nation of Venezuela was built on the production of chocolate, as was Ecuador.

Chocolate and Africa go hand in hand: the vast majority of modern chocolate is produced in West Africa... by child slaves. There's a reason I called this the FIRST one with slavery. Hope you were planning on cutting back on chocolate, because some of the later entries in this blog may make you want to never touch the stuff ever again.

0 notes

Text

Part 3: Colonial Consumption

Pictured above: a 17th century "Chocolate House" in England. These rambunctious cocoa houses served as meeting points for London's elite.

By the end of the 16th century, Europeans had finally come around to appreciate Chocolate. Once ignored as a vaguely medicinal "savage" drink, it soon became a luxury good.

Before this, Catholic priests had even condemned chocolate as a pagan concoction causing gluttony, lust and greed. Rumors abounded of pregnant women who ate chocolate giving birth to unnaturally colored babies, or that the Devil himself had appeared in cups of hot chocolate. All this even after the Spaniards had added vanilla and sugar to the mix.

But to be fair, there were actual cases of witchcraft involving chocolate. (That is a very rare sentence. Treasure it) Women in colonial Mexico would brew chocolate drinks mixed with ritual spices and give it to men they fancied: it was believed that if a woman gave these ritual drinks to a man, the man would instantly fall in love with them. (As far as I can tell, this did not influence the Valentine's Day Whitman's Sampler, it's just a funny coincidence)

Shops selling chocolate, alongside the other exotic hot beverages of coffee and tea, began springing up in England. The first recipes for chocolate in English come from the Earl of Sandwich, who has served as ambassador to the Spanish court, in the latter half of the 16th century, including one for a frozen chocolate treat. Chocolate began to be seen as a luxury good. Since most chocolate producing regions were under the control of the Spanish Empire, it meant that it was more expensive than coffee or tea. King Charles was a connoisseur of the stuff, having paid the Earl of Sandwich £200 (a fortune in those days) to get a recipe.

As the popularity of chocolate grew across Europe, production increased. And as always, that means more slavery.

This is gonna get really dark...

0 notes

Text

Part 2: When Europe First Discovered Chocolate

Pictured above: a fanciful painting by a European of Native Americans preparing Chocolate. Taken from the encyclopedia Ogilvy's America, published in 1671

In 1502, Christopher Columbus (may he rot in hell for eternity) and his son Ferdinand went on a voyage to what is now called Central America. While there, Ferdinand writes about eating "brown almonds"...in reality, cacao beans.

While Columbus took some of the beans back to Spain, Europeans would only truly encounter chocolate after Hernan Cortes's conquest of Mesoamerica. Moctezuma prepared fifty jars of foaming xocalatl for Cortes. This was the beginning of a love affair that would have major consequences for the world. Many writers have described the Columbian Exchange--the flow of goods and culture between Europe and the "New World" in the Americas--as the beginning of modern economic globalization. But it took a while for the European palette to accept chocolate. The old myth was that the Spanish "improved" the flavor by making it sweeter, as Europeans could not take the harsh and bitter flavor of Mesoamerican chocolate. But Marcy Norton argues that the Spanish had already unwittingly gained a taste for the Mesoamerican chocolate, and sought to recreate it in Europe.

It took a while for chocolate to become the sweet dessert we know today. Initially, it was touted as medicine. As late as 1631, over a century after Cortes and his party arrived at Tenochtitlan, an Andalusian doctor named Antonio Colmenero Ledesma published a treatise on the medicinal use of chocolate...and the recipe provided is very similar to that provided in the Florentine Codex. Ledesma recommended this concoction to aid in childbirth, helping digestion and curing gut disease. Historian Marcy Norton argued that this discourse was made by Europeans to justify their consumption of this "savage" food product. Considering what happened to acai berries after white Americans discovered that they were a "superfood", I'm inclined to believe her.

Nevertheless, chocolate played a key role in European colonization. Chocolate plantations were common in Latin America, especially in the tropical regions near the equator. The growing demand for the foodstuff led to more and more colonies making chocolate to keep up with demand.

0 notes

Text

Introduction: The Origins of Chocolate

Hello. This blog will focus on the history of chocolate.

The history of chocolate is a bit like Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory: charming and colorful on the surface but dark and unsettling once you peel back the layers. Most people don’t want to think about colonialism, genocide, slavery, exploitation, pollution, or corporate greed when they break off a piece of that Kit-Kat bar, but Western society’s chocolate habit has always been at the expense of poorer nations.

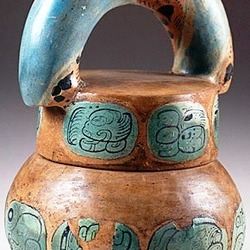

We must begin by discussing where chocolate came from: Mesoamerica. Below is a Maya chocolate pot, found in a king's tomb in Guatemala.

All alone I sing to him who is my god. In the place of light and heat, in the place of the world, the cacao has flowered, is frothing, and the drink, that inebriates with flowers. I breathe it in, my heart savors it, my heart is inebriated, in truth my heart knows it: Hail redness of rubber collar! fresh and fiery, you light your garland of flowers, O mother! Sweet, delicious mother, precious flower of roast corn, you only offer yourself, you shall be abandoned, you shall have to depart, you shall remain unfleshed. Here you have come, before the princes, you, marvelous creation, inviting to pleasure. On the mat of blue and yellow feathers here you are set up. Precious flower of roast corn, you only offer yourself you shall be abandoned, you shall have to depart, you shall remain unfleshed. [...] The cacao in flower is already frothing, the flower of tobacco is shared out. My heart if it wished would be inebriated... “All Alone, I Sing” Tlaltecatzin of Cuauhchinanco. Translated by Timothy Ades

Let this poem set the tone.

Chocolate began in ancient Mesoamerica. It was discovered by the Olmecs, refined by the Maya who first called it Cacao, and then given to the Mexica (or Aztecs) who gave it the name "chocolate". Ancient Maya, Aztec and Olmecs created chocolate plantations and were the first to ferment, roast and grind the beans into a powder or paste. And while we associate chocolate with desserts, the Mesomarericans used it as a spice and a drink. The Aztecs named the drink Xocatl, which is where we get the word "chocolate" from. As a drink, cacao was enjoyed by the upper classes of their society, a symbol of wealth and power linking them to the Gods. It was an important part of culture in Mesoamerican society, with the plant playing a significant role in mythology, religion, culture and commerce. They considered it the “tree of life”, and the cacao beverage to be the “food of the Gods”--something sacred to be protected, not a cheap mass-produced snack product the way we view it today. Cacao beans were used as currency and as a tax paid to the government–a 1545 document written in the Nahutl language of the in the Aztec empire shows that the daily wage of an Aztec porter was 100 cacao seeds, a turkey was worth 200 seeds, and a tamale from a street vendor was worth one seed. They were often given as gifts to celebrate births, marriages and initiations into society. Thanks to a funerary bowl discovered in southern Belize, we know that cacao beans were sometimes even buried with dead bodies to guarantee safe passage into the afterlife, much like how ancient Greeks would bury their dead with coins to give to Charon.

Rather than a commodity to be bought and sold, the Mesoamericans viewed chocolate as something more than that. It was food, it was currency, and it was sacred, representing power, wealth, and their Gods. This would change once the Spanish Empire made contact with the Mexica, and discovered the mysterious brown bean that would eventually change the world forever…

0 notes