Text

Reminder: the companies and political entities pushing Project 2025 have addresses and go out to lunch a lot and should never eat a spitless meal for the rest of their lives.

Practice bagpipes outside their secure compounds.

Follow them around ringing a bell wherever they go.

If they are going to be farcically evil, be Animaniacally good. Be the definition of chaotic justice.

Also, vote. It might just kick the ball down the road a bit, but that gives people more time to organize a concerted resistance (in no way on any social media platform) to the fascist creep happening in America. It is possible to take this country from the bastards who control it, it will take work, effort, and occasionally going offline and talking to humans though.

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

I have a new favorite company, I kinda want one of most of these.

https://www.untamedego.com/collections/womens/products/copy-of-have-the-day-you-deserve-exclusive-tee

0 notes

Text

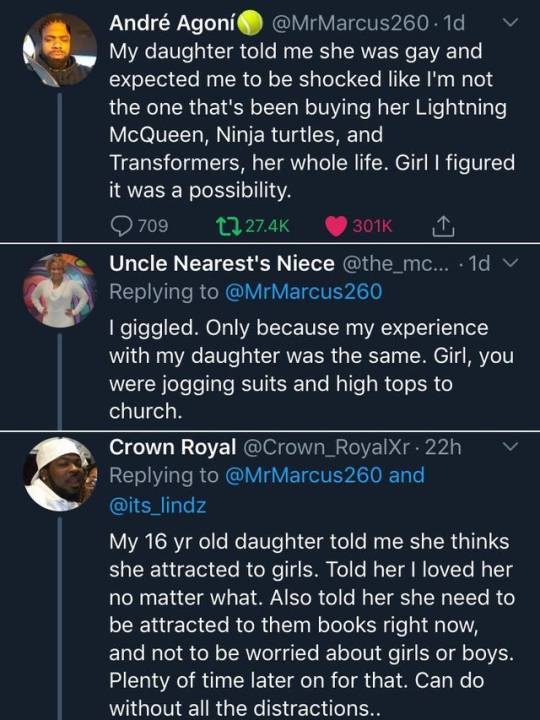

One of the funniest failures of US school system is the fact they are legally obligated to teach us all the states but they never actually show how big Alaska is like I have actually had teachers tell me that Texas is the biggest state. We have all just convinced ourselves that Alaska is that small shrunken down thing on most US maps and the people that know it's the largest state can almost never accurately describe how large it is.

For context here is a picture

265K notes

·

View notes

Photo

USA - exaggerated relief map with elevation tint.

by u/helloVizart

950 notes

·

View notes

Text

40K notes

·

View notes

Text

gosh but like we spent hundreds of years looking up at the stars and wondering “is there anybody out there” and hoping and guessing and imagining

because we as a species were so lonely and we wanted friends so bad, we wanted to meet other species and we wanted to talk to them and we wanted to learn from them and to stop being the only people in the universe

and we started realizing that things were maybe not going so good for us— we got scared that we were going to blow each other up, we got scared that we were going to break our planet permanently, we got scared that in a hundred years we were all going to be dead and gone and even if there were other people out there, we’d never get to meet them

and then

we built robots?

and we gave them names and we gave them brains made out of silicon and we pretended they were people and we told them hey you wanna go exploring, and of course they did, because we had made them in our own image

and maybe in a hundred years we won’t be around any more, maybe yeah the planet will be a mess and we’ll all be dead, and if other people come from the stars we won’t be around to meet them and say hi! how are you! we’re people, too! you’re not alone any more!, maybe we’ll be gone

but we built robots, who have beat-up hulls and metal brains, and who have names; and if the other people come and say, who were these people? what were they like?

the robots can say, when they made us, they called us discovery; they called us curiosity; they called us explorer; they called us spirit. they must have thought that was important.

and they told us to tell you hello.

447K notes

·

View notes

Note

For the ask... anagapesis + Grindeldore?

anagapesis — the feeling when one no longer loves someone they once did

The grass of the field where Grindelwald will die is soft, green and deep. A little worse for the wear, perhaps; heeled boots and magic have churned up the dirt and left the ground bald in places, but at least there’s no blood. (The one benefit of a wizarding war, instead of the other sort: very little blood, as a rule.) The sky is an unending vault of blue—even the smoke billowing from the scorched oak doesn’t stay for long, borne away on the breeze.

It seems like a fine enough place to die, if you ignore the bodies.

If Grindelwald falls back—and he should fall back, Albus knows the crude mechanics of this unforgivable Unforgivable thing—he will be facing up at the sky. He won’t have to see the bodies at all. The grass is soft and deep, it will swallow him up; it will be like nothing. Like smoke disappearing on the wind, or falling asleep.

Grindelwald is watching Albus through narrowed eyes, clutching at his own shoulder. Grindelwald’s blood is red. (Very little blood, we said, not none.) It surprises Albus, how red Grindelwald’s blood is. It is somehow realer than the rest of him, even more than the long dark wand in his sinister hand, and Albus had thought nothing could be more real than that.

“I know what you’re thinking, Albus,” Grindelwald says, and Albus lifts his eyes from that blood, red on Grindelwald’s fingers. Grindelwald grins.

“You always did,” Albus says mildly. He brings his own wand up, but he cannot remember of the right angle just yet. He lowers it again. “What am I thinking, then?”

“That night, on the lake.”

Albus had not been thinking about that, though he is thinking about it now. “What about it?”

“You told me that your mother had Neapolitan blood—a touch of the Sibyl in her. Just enough that she could see a man’s death, if she looked hard enough. Do you think she saw yours or mine, here?”

Albus forgot that conversation. (He remembers other things about the lake, like how Albus had laughed as Gellert fumbled with his robes, too distracted by the sight of Albus skinny-dipping to manage the clasps; the heat of Gellert’s hand, the way that he cursed in Sanskrit as he came.) But it is true that his mother bragged of her limited Sight, and….well, Albus has always had a bad habit of forgetting things when it comes to Gellert. The mania. The possessiveness. The delirium of being near him. Even now, Albus can’t help but think he’s forgotten how dark Gellert’s eyes are, the way he moves when dueling, the brightness of his hair—more like polished silver than gold, but still fair and beaten into shining.

“She never told me,” Albus says mildly. “And so I cannot tell you.”

“Pity,” Gellert answers. “She could have settled this before it began. It would have been convenient.”

“That’s not…” Albus shakes his head. His wand feels very heavy in his hand, a leaden weight, a cauldron full of the poison that lies between them—whole oceans of it. “You are nothing to do with ‘convenient,’ you know this.”

Gellert laugh without even a shred of humor. It is awful, it makes Albus flinch; and then Gellert is silent again. After a long while of their staring at one another, he sighs, and offers up his hands: one with the long dark wand still caught in his long fingers, the other stained red.

“Come closer,” Gellert says, and he said that before, at the lake. (His hands were so hot, Albus had felt he was burning up under that touch.)

Albus exhales shakily. “I do not trust you.”

Gellert smiles, and it’s a boy’s trick, a jade’s trick, when he flips the long, dark wand so he is holding it grip-out. “Please. I will not hurt you. Not you.”

Albus is close enough to dig the tip of his wand into Gellert’s throat before he trusts he is in earnest. “And now?” Albus asks, feeling queerly out of breath, dizzy with sme feeling he cannot name. (They are so close. They are close enough that Albus could lean in, and—)

“You could kill me,” Gellert says with the old mischievous grin. It looks strange on his weathered face, with its scars and the beginnings of softness, at his jaw—they were so young when they started this. Albus has taken too long to finish it. “You could, Albus.”

“I know.”

“I would let you,” Gellert says, and Albus hesitates. Underneath the grin is an edge like a blade. It is sharp enough that it could cut, deep, into Albus—it could cut to the bone. Albus could be bleeding out now, and not notice.

“You would?” Albus asks mildly.

Albus knows that a quick and clean death under the sky is Right. It would be Right and Just and Merciful, which are words Albus vaguely recognizes, even if the only emotion they elicit is a hollow ache. Gellert tilts back his head, and the tip of Albus’s wand slips down his neck—to rest just above his Adam’s apple. When Gellert swallows, Dumbledore’s hand moves. There is a metaphor in that; Albus can’t follow the thread of what it means just now.

“Or,” Albus says, and Gellert smiles horribly. It is one of his old smiles, the sort from the lake. From those stolen, golden hours at the Manor or further afield, when Gellert pressed Albus against the altar in that Muggle church they stole into, when he looked at Albus and looked and looked, and then said, you know, they believe that this is a threshold; here is where a man is broken open and becomes a god.

It is a terrible smile; it inspires terror.

(I love you, Albus thinks uselessly, helplessly—a different sort of love than before. Something natural turned to poison, and rotting away at his insides. But he cannot stop it, turn it away; there is no magic that will collect this from his blood and pour it harmlessly onto the grass. Albus must endure the horrible loving of Gellert, even now. Even here.)

“You could take me back to London,” Gellert says gently, though his eyes burn with violent fever-light. “Parade me in front of the Wizengamot, show me off to all of Wizarding Britain. The Terror of Europe under your power. Shove me in front of a crowd, I’ll scowl and spit—your trophy, better than any Order of Merlin. ‘Dumbledore’s triumph,’ they’ll say. ‘Dumbledore’s pet monster.’ They won’t deny you anything, Albus. Everything we ever dreamed of—more, even. The hero, unconquered.”

“I don’t want…” Albus breathes, and Gellert cocks his head.

“Don’t you, though?” he asks. His eyes are so dark, as dark as they had been at the lake. He is right, in some twisted way—Albus does want. Albus can bury himself alive in researching uses for dragon’s blood and stuff himself with canapes at Ministry parties, demurring anytime the subject of war arises, but underneath he wants and wants and wants, some things he daren’t even speak aloud.

That was the problem with Gellert: Albus could tell when he lied, so he never bothered.

Albus exhales. He shut his eyes once, standing in the family manse with a white-knuckled grip on his wand. Aberforth had been shouting about foreign perversion as Gellert crowed about country ignorance, and there, just there, had Ariana stood in the doorway, very pale except for her flaming hair. It had been selfish, shutting his eyes then—easier than the alternative, simpler than to make himself see. And Ariana had died like that, with Albus’ eyes shut. (That was easier too.)

Here is the great, grave secret It’s easy to just….keep being selfish. To lean in, until his wand is digging into the hollow of Gellert’s throat. To press his forehead to Gellert’s forehead and kiss Gellert’s mouth with his mouth. To hold him there, pinned like an insect to a board, until Albus is dizzy with the closeness of him and the smell of smoke, spell-residue on their fingers.

“All right,” Albus murmurs. “All right.”

Gellert exhales. Albus inhales. There is no one around to see them but the dead, and they have their eyes turned up to the sky.

(This is the last time they touch for fifty years.)

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes I look through old archives of the internet and wonder just how much has been lost. If what we have collectively preserved publicly is so massive, how much art has been left to fall between the gaps in the records. What has been lost to time, disintegrated by the disinterest of people. I mean, sure, maybe a lot of it was useless to most, but if even one percentage of the information that has been lost was valuable, then humanity has suffered greatly. I find myself remembering a time I walked through a pine forest, and seeing the various bits of plastic and waste left along the pathways and even taking up the hidden corners as well. Much like the idea of lost history, most of this stuff is discarded because of disinterest or inconvenience/laziness. But when I looked hard, I found things I wished I could use, if only time had not eroded them and left them beyond repair. An old car, with a partially intact engine decomposed by rust. A wooden pole, half eaten by the water it sat in. The fallen branches, however, were still usable. The vines and the bushes still lived on. Despite all that is lost, life continues to push forward towards its own inevitable demise. The feeling this leaves me with is a wistful sadness, a sort of soul-twisting, stomach clenching sense of dissonance. Despite all this, I continue on, I do not stop, marching in time with the heart that will eventually fail. Using the legs which will inevitably falter. Breathing with lungs that will collapse. Thinking with a brain that will simply not last. And yet, I still march. Maybe I am just like a discarded piece of plastic, incompatible with my surroundings, and yet refusing to deteriorate because of my design.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Having a traumatic childhood means you cannot talk even objectively about your basic foundational experiences without it being "venting", even if you're not actually venting. You just straight up have a huge chunk of your life you can't talk about, full stop, without it being trauma dumping.

And it not being socially acceptable to talk about your own childhood is super alienating. Sometimes people want to know why, and any answer you can give them is going to be off putting.

It's to the point I get irritated when something I said is framed as venting when I'm literally just talking about my life experiences, doing my best to keep emotion out of it.

108K notes

·

View notes

Text

So uh….some dude apparently recreated Adobe Photoshop feature-for-feature, for FREE, and it runs in your browser.

Anyway, fuck Adobe, and enjoy!

401K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey, if you're a minor and you're following my blog, I just need you to be aware:

You have been on this earth for fewer years than my cat has.

She turns 20 this week, everyone please say happy birthday 🥳💖

286K notes

·

View notes

Text

Legitly good music for studying or vibing

youtube

0 notes

Text

I hate that I’m always trying to find cool biology themed stuff to wear but all the “nature inspired” clothing companies just have like two crossed arrows or a minimalistic mountain on a sweatshirt. Fucking lame, that’s barely even nature-adjacent. Put the life cycle of a salamander on a jacket, put hyena skeleton patterns on leggings, put a damn field guide of birds of prey on a peacoat and THEN you can have my money. Do NOT give me a shirt with a leaf on it that says “stay wild” or some bullshit I would much prefer clothing that broadcasts to everyone around me how many teeth an adult Jaguar has or how some pitcher plants can catch and digest rats.

105K notes

·

View notes

Text

“To see a world in a grain of sand, And a heaven in a wild flower. To hold infinity in the palm of your hand, And eternity in an hour.”

— William Blake, Auguries of Innocence

326 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Cataclysm Sentence, a collection of advice for The End.

"To explain: one day in 1961, the famous physicist Richard Feynman stepped in front of a Caltech lecture hall and posed this question to a group of undergraduate students: “If, in some cataclysm, all of scientific knowledge were to be destroyed, and only one sentence was passed on to the next generation of creatures, what statement would contain the most information in the fewest words?” Now, Feynman had an answer to his own question—a good one. But his question got the entire team at Radiolab wondering, what did his sentence leave out? So we posed Feynman’s cataclysm question to some of our favorite writers, artists, historians, futurists—all kinds of great thinkers. We asked them “What’s the one sentence you would want to pass on to the next generation that would contain the most information in the fewest words?” What came back was an explosive collage of what it means to be alive right here and now, and what we want to say before we go."

2 notes

·

View notes