Text

The poetic art of Hossein Valamanesh

The art of Hossein Valamanesh is remarkably universal in its resonance and exploration of the human condition. At the same time, his work engages with the specificities and complexities of being an Iranian migrant in an Australian context. The artist collapses the opposition between art and life through the aesthetic languages of sentimentality, mysticism and poetry. There is a sense in which the artist’s work cannot be neatly categorised and operates outside the confines of the art historical cannon. Sufi mysticism infuses the artist’s work, in which paradox and an ethic of love are central. By reading the artist’s works of art through the lens of performance, a range of questions surface regarding the role of ritual, the body, materiality, and presence and absence. In terms of the artist’s sense of place in the Australian context, there is a quality of ambivalence, and a lack of resolution. Belonging remains an open question to be explored ad infinitum.

Valamanesh does not fit neatly into the art historical canon, while neither foregoing associations entirely. A conventional reading of his work might place it within the genres of conceptual art or minimalism. However, this semantic enclosure would unnecessarily tame the artist and works of art. By evoking quiet awe, reverence, and enchantment, there is a sense in which the works of art demand to be thoroughly experienced and felt rather than merely understood and catalogued. This echoes the artists’ own confession of having only a minimal interest in the cannon. This (dis)interest may reflect the artist’s awareness of the European bias in the discipline of art history. Undergirding this is a tender yet relaxed commitment to personal truth, however not one that can solidify into finality. Valamanesh’s orientation to the art world is encapsulated by a poetic sensibility through which he views the artist as lover. He maintains that the idea of love is not an answer but rather, a guiding question animating art and life. When describing his decision to pursue art as a way of life, Valamanesh confesses, “I have stepped into the path of love” (Arnold 2013, 136).

Valamanesh’s approach to art entails a richness and complexity that draws on spirituality and embodies a metaphysical curiosity. The Lover Circles His Own Heart (1993), (Figure 1), consists of a silk skirt suspended and spinning continuously in the gallery space, reminiscent of the “whirling dervishes” of Islamic Sufi mysticism. The work of art uses movement to conjure a sense of the real life dancing of devotees of the Mevlevi Order of Sufism. The whirling is a physical meditation thought to bring devotees closer to the divine (Museum of Contemporary Art Australia 2018). Movement is also a metaphor for impermanence, a recurring theme throughout the artist’s work. In a formal art historical sense, it employs the idea of duration and it does so without video or the physical presence of a performer. In a metaphysical sense, the continuous spinning of the skirt, without beginning or end, suggests the notion of infinity. Valamanesh does not describe himself or his works of art as religious. Yet, there is an undeniable spirituality in The Lover Circles His Own Heart (1993), the title of which is a line from a poem written by Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Balki, otherwise known as Rumi. This liminality or in-betweenness is the defining feature of mysticism and is present in the artist’s works of art in several important ways: through the enchantment of everyday materiality, cultural juxtapositions, and the use of real and represented objects simultaneously.

The artist’s use of everyday or found materials is not driven by an art historical reaction to established norms, such as Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) and its commitment to the supremacy of the concept or idea. Valamanesh uses everyday materials with the intention of transforming what is personal, intimate or close at hand – everyday lived experience – into art. In contrast to Duchamp, Valamanesh’s works of art prioritise emotional expression, sentimentality and an intellectual humility. The artist uses textiles and clothing, as well as materials requiring little human intervention such as branches, twigs, sand, water, and fire. There is a recurring sense of ephemerality in the choice of materials, including a ritual enactment of said ephemerality. In Longing Belonging (1997), (Figure 2), a hand-made Iranian carpet is shown with a campfire burning in its center against the surrounding bush land. The placement of materials creates rich juxtapositions in the artist’s work: an Iranian hand-made carpet situated in the Australian landscape, and its final presentation as a burned carpet brings Iranian domesticity inside the artificial gallery space. These assemblages play on binary oppositions of permanence/impermanence, nature/culture, creation/destruction, public/private, native/settler and oriental/occidental. Longing Belonging (1997), in particular, expresses a sense of ritual and performance that I argue is central to Valamanesh’s works of art.

While Valamanesh’s works of art are not immediately read as performance art in the sense of live performers, generation of a live ‘event’ or viewer participation, they are performative through the use of ritual. Marsh suggests ritual and performance art are different, maintaining that ritual enacts closure or resolution whereas performance art tends to remain open-ended. (Marsh 2017, 5) Valamanesh’s works often allude to, document or exhibit an index or trace of the ritual performance. In Longing Belonging (1997), the viewer is presented with a documentary-style photograph of the event or ritual burning. The photograph acts as a translation of a ritual act that was a once off gesture. This translation of a live event into a timeless image contrasts with the ephemerality of the burning ritual. Both the photograph and burned carpet act as signifiers of memory (of a past live event), which Marsh (2017) argues constitutes a growing form of contemporary performance expression. (Marsh 2017, 5) The use of fire is a form of considered destruction and transformation of the art object. It carries further associations of renewal, violence, cleansing, regeneration, and fecundity in relation to the Australian landscape. There is a sense of the artist’s desire to find a meaningful relation between two (or multiple) homelands, landscapes, identities, and the complexities this search entails. The imagery is evocative of the environmental rituals of urban Australians who may in fact use camping as a balm to the “crisis of late modernity” (Marsh 2017, 5).

Performance art is often associated with the body and Valamanesh’s works of art involve the body (including his own) in unconventional and complex ways. Centering the physical body within art disrupts Platonic and Cartesian dualisms and has been strongly influenced by feminist, queer and people of colour artists and philosophers (Grosz 1994). Art historian, Peggy Phelan, argues that live performance involves “presence” and the possibility that “something transformative might occur in the scene of enactment that cannot be fully rehearsed”. (Phelan 2007, 355) However, Amelia Jones contends that performance works can retain impact through documentation and that photography is itself a performative medium. (Marsh 2017, 10) Coupled with an analysis of a Western preoccupation with presence over absence, or visibility over invisibility, the notion of performance can be stretched to incorporate Valamanesh’s works of art, including Longing Belonging (1997), in particular (Hudson 2006, 10). The body in Longing Belonging (1997) is present through its absence. Somebody lit the campfire and its documentation was also made possible through a body. The carpet is burned but not unusable, its presence evokes the body through the possibility of touch and daily use, even if this is not permissible within the gallery. Similarly, The Lover Circles His Own Heart (1993) involves the absent body as an imaginative force inside the moving skirt. In other works of art, Valamanesh is present and absent through the use of shadow and silhouette. Marsh suggests this extension or ‘flattening’ of presence can protect as well as position the viewer as voyeur. (Marsh 2017, 10)

The works of art created by Valamanesh are strongly linked to his experience as a migrant. They present an emotional commentary on the experience of being Other in an Australian context, the weight of cultural memory, and the search for a sense of place. Longing Belonging (1997), whilst easily experienced as a catharsis, is also an infinite regression of landscapes held in tension: the landscape depicted on the Iranian carpet (its floral fields, enclosed courtyard and reference to the mythic garden of paradise), the landscape of the Australian bush or desert in the background photograph, and the landscape of the contemporary gallery. Each landscape carries mythologies that generate consonance and dissonance, intelligibility and unintelligibility. There is a sense in which things remain out of place at the same time as poised for integration, transformation and resolution, whilst never wholly achieving either. Also noteworthy is the placement of the carpet outdoors, namely, in public space. This is both an aesthetic inversion (an indoors object placed outdoors) and a political gesture that disrupts the pressure upon cultural minorities to limit cultural practices to the private sphere. The use of fire is also evocative of ancient and contemporary relationships to the Australian landscape where fire remains an important source of regeneration and Aboriginality, and yet is also framed as an immanent threat to sedentary lives and environments.

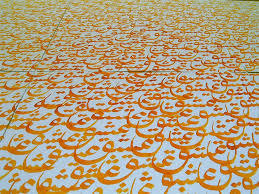

Valamanesh draws on Persian textual traditions through the use of poetry and poetic titles for his works of art. The artist draws primarily on the Sufi poetry of Rumi. Poetry, for Valamanesh, is a form of movement and reflects life itself (Sarah 2012). The influence of poetry can be seen not only through the use of literal text on a gallery wall, but also as present in the materiality of each work of art as a whole. The Lover Circles His Own Heart (1993), is a line taken from a poem by Rumi and evokes a physical gesture that is both cyclical and unending. The artist uses English text and Islamic calligraphy, the latter often arranged in a way to emphasise the materiality or imagery of the word (Pervis 2017, 43; Thomas 2007, 62). This enacts a subtle subversion of the written word, due to its connotations of rationality, transparency, eternity and civilisation. Instead, text becomes more than a message, it is also a “form of drawing”, an ornament, decoration and as such, impermanent (Thomas 2007, 62). The use of Islamic calligraphy is also a way to “imbue Western modernism with a cultural specificity” (Thomas 2007, 63). In the Australian context, the use of the Farsi language in the artist’s work creates an “indecipherability” for many (non-Islamic) viewers, further enhancing the visual (even sensual) experience of text rather than “reading” its meaning (Thomas 2007, 63). Therefore, the artist’s work contains the paradox (a principle at the heart of Sufism) of attempting to represent the unrepresentable through language, without diminishing either experience.

The art of Hossein Valamanesh is a quiet invitation into the wholeness of mystery, love, and movement. The sense of impermanence of all things is reflected in his appreciation of the opportunity to continue to work, rather than amass prestige or fame. His art draws on the aesthetics of sentimentality, mysticism and poetry to evoke an embodied experience in the viewer. Performance is apparent in his works of art through ritual, the absent body and documentation or translation. My own artistic practice resonates with the artist’s work. I experience a sense of relief from the (masculinist) strictures of ideology, irony, disembodied intellectualism, and interrogation that has characterised much contemporary art in the late modern period. Valamanesh offers a simple and enduring legacy of the artist as lover, and the metaphysical curiosity this inspires.

Images

Figure: 1. Hossein Valamanesh, The Lover Circles His Own Heart (1993), silk, electric motor, foam, brass rod, stainless steel cable, wood, poem, 210 x 210 x 210 cm. Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney.

Figure: 2. Hossein Valamanesh, Longing Belonging (1997), direct colour positive photograph, carpet, velvet, 99 x 99 cm (colour photograph) 215 x 305 cm (carpet), Art Gallery of New South Wales (not on display), Sydney

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rights, recognition and the view from nowhere

Introduction

Land claims are an important site of Settler-Indigenous knowledge-power relations. In Foucault’s terms, a hierarchy of knowledges compete with one another in court. Legal positivism limits what knowledge is permissible as evidence and how knowledge can be demonstrated, such as written trumping oral sources. In contrast to this repressive dimension, power is also productive of Indigenous knowledges and identities. Liberal recognition entails negation (erasure, silencing) and risks reproducing forms of power that Indigenous people’s demands for recognition typically seek to transcend. Its key vehicle, the rights discourse, incorporates difference, which leads to its transformation. Meanwhile, the limitations of ‘public’ debate mask difference. Spivakian theory is used to identify the structure of this debate in which the subaltern cannot speak on her/his/their own terms. It is suggested that these terms are underpinned by a universal/particular binary in which Whiteness functions as a ‘perspectiveless’ standpoint (an oxymoron, right?)

Enforced commensurability

Native title is a construct of the common law and although it ‘radically changed the fundamental assumptions of Australian property law’ (Falk and Martin, 2007: 34) it also codifies Indigenous ontological relationships to land in incommensurable ways thereby ‘delimiting and forcefully re-shaping the character of Indigenous ties to land’ (Smith and Morphy, 2007:2, Fisher, 2008: 2). For example, native title configures land ownership as a property right and privileges physical presence in accordance with ‘signifiers of white possession’ such as ‘fences, title deeds, [and] residences’ (Moreton-Robinson, 2004[1]). Furthermore, native title pertains only to land thereby compartmentalising what is otherwise a whole system covering every aspect of life. These ‘rights’ are further reduced to ‘discrete rights to use of the land’ and are ‘vulnerable to extinguishment by almost all subsequent interests in the land’ (Curthoys, 2008: 63). However, the notion of ‘extinguishment’ is rejected by Moreton-Robinson (2004) because Indigenous people ‘carry title to the land through and on their bodies…the relationship between people and their country is synonymous and symbiotic. This is why the connection to land is never broken’.

The ‘enforced commensurability’ of land claims is an outcome of the ‘space of recognition’ where Indigenous knowledges must be made recognisable to White law and meet legislative requirements (Morphy, 2007:33). Therefore, rather than simply disqualifying certain knowledges (non-conceptual, naïve, inferior, unscientific and so on) in Foucault’s terms (2003:7-8), land claims actively appropriate and produce representations of Indigenous knowledges. Indigenous claimants are called upon to articulate group and territorial boundaries within anthropological models that emphasise “ownership of discrete estates, including defined tracts of land, by clans constituted through patrilineal descent” (Smith, 2003:135). Extensive anthropological genealogies are privileged when defining the claimant group. Whereas genealogical knowledge tends to be shallow and focused on classificatory (society wide) kinship relations, which reflects an interest in the ‘spread or scatter of relationships’ (Freeman in Smith, 2003:134).

Power as productive: identities

Land claims produce representations of Indigenous knowledges and identities. The distinction made between tradition and history either denies or places an arbitrary limit on cultural change in judicial interpretations of ‘tradition’ and ‘continuity’ – that is, change due to dispossession and the creativity of Indigenous responses to colonisation (Povinelli, 2002:7). For example, when the Larrakia people formed an umbrella organisation to unify competing native title claims it was cited as evidence that traditional decision-making practices had been lost (Smith and Morphy, 2007:14). This ensures that colonised subjects identify not with the coloniser but with ‘the impossible object of an authentic self-identity…a domesticated nonconflictual ‘traditional’ form of sociality and (inter)subjectivity’ (Povinelli, 2002:6). Anthropologists may collude by ignoring or diminishing emphasis on Christian belief and practice (Trigger and Asche, 2010:91) or the syncretic interpenetration of cattle station and traditional life (Smith, 2003:137). To make matters more difficult, claimants must simultaneously “ghost this being for the nation so as not to have their desires for some economic certainty in their lives appear opportunistic” (Povinelli, 2002:8).

Knowledge as evidence: orality and textuality

In the context of cultural heritage and land claims, Indigenous peoples face further challenges. The judicio-political context is underpinned by epistemological positivism. This is not simply a body of knowledge but a theory or ‘science of how knowledge can be understood’ (Smith, 1999:43). Although the empirical method underpinning positivism can resonate with Indigenous epistemologies, positivism promotes ‘a set of values, a different conceptualisation of such things as time, space and subjectivity, different and competing theories of knowledge and, highly specialized forms of language and structures of power’ (Smith, 1999:42). These manifest in judicio-political contexts such as land claims, particularly in the rules determining permissible evidence or proof. In addition, the hierarchicalisation of knowledges is closely tied to the epistemological standpoint of the judicio-political context.

Objectivity is the belief in a space unmarked by and distanced from human emotion and subjective experience. Objective knowledge is untainted by these lesser knowledges and ways of knowing and thus acquires the status of ‘factuality, logic and common sense’ (Curthoys, 2008:180). In court, oral and written sources of evidence are subject to a hierarchical distinction between objective and subjective knowledge, respectively. Therefore, written sources are privileged over oral sources, clearly marginalising Indigenous peoples who – whilst not without forms of textual expression – pass on and acquire knowledge primarily through oral practices.

Oral testimony is permitted under certain conditions. For example, second-hand knowledge or ‘hearsay’ requires a witness, without which it can only be admitted as ‘belief’, but not as ‘fact’ (Curthoys, 2008:73). Whether knowledge meets the criteria for judicial evidence determines what value it is attributed and/or whether it is admitted. Written sources, which are attributed objective status, tend to derive from police, court and prison records promulgating assumptions of a ‘dying race’, which diminish prospects for recognition (Curthoys, 2008:84). Claimants’ knowledge must be translated into written form through connection reports and witness statements. Thus, ‘Indigenous stories are treated as ‘oral’ even when they are presented in written form’ (Nicoll, 2000:372).

Historical evidence and modernity

Cultural heritage and land claims require proof that Indigenous peoples’ laws and customs existed at the time of European ‘contact’ and remain unbroken. This means that historical evidence is central to legal determination. However, because this knowledge is often ‘outside the experience of living witnesses’ (Curthoys, 2008:61) past anthropological literature is privileged over contemporary anthropological reports. The applicants to the Hindmarsh Island Bridge case argued that the text ‘The World That Was’ by anthropologists Berndt & Berndt – suggesting the unlikelihood of further secret knowledge beyond which they had already documented – be treated with more authority than the anthropological report produced for the case on Ngarrendjeri women’s sacred knowledge (Curthoys, 2008:184). The applicants charged the anthropologist’s fieldwork with ‘methodological presentism’, the practice of construing present conditions as how they have always been (Curthoys, 2008:88). Therefore, a particular theory of history is privileged that militates against Indigenous peoples in cultural heritage and land claims.

History is not only contested narrative accounts but also contested theories. The High Court Mabo decision exemplifies the former – a contested and partially resolved account of history. Subsequent land claims are set within an a priori denial of Indigenous sovereignty. Similarly, the disciplines of anthropology, history, law and government archives seek to influence the historical record. This takes place within the modernist project of history, which is based on the following ideas: that history is a totalising discourse; is universal, chronological, developmentalist and innocent; and aims for self-actualisation of the human subject (Smith, 1999:30). Oral histories, as ways of knowing, reveal that historical memory is not necessarily linear, chronological and progress-oriented (Corntassel, 2008: 117). For example, Bird-Rose (2000:203) has described the Yarralin people’s concept of time as a quality of life, reflected in practices such as shallow genealogies and rituals of forgetting the deceased. In the Hindmarsh Island case, instead of challenging the historical criteria at play, anthropologists argued for a contextual interpretation of the Berndt’s text: that during the Berndt’s fieldwork no immediate threat existed that might have motivated disclosure of secret knowledge (Curthoys, 2008:187). This response eventually won favour, however it fails to challenge the epistemological and theoretical assumptions of the modernist project of history.

Rights discourse reproduces hegemony

The rights discourse risks re-inscribing certain forms of power that are capable of continuing both disavowal and recognition. Glen Coulthard (Corntasesel, 2008:115) argues that ‘the politics of recognition in its contemporary form promises to reproduce the very configurations of colonial power that Indigenous peoples’ demand for recognition have historically sought to transcend’. For example, to go beyond recognition of Indigenous peoples’ prior occupancy in the High Court Mabo decision was deemed to threaten the skeleton of the Australian legal system (Moreton-Robinson, 2004). In response, the question of Crown sovereignty was judged to be non justiciable (Watson, 2002). Manderson (2008:236) argues that the inauguration and suspension of law amounts to a legal black hole or what legal theorist Carl Schmitt terms a ‘state of exception’, a form of ‘power…that inheres in the nature of sovereignty.’ Therefore, despite the seventeenth century shift from sovereign power (‘to let live or die’) to disciplinary power (‘to let live and to make live’), the former persists whilst becoming expert at concealing itself (Brigg, 2010:412). Both sovereign and disciplinary power continue to co-exist in the context of cultural heritage and land claims, disguised behind the veil of recognition.

Recognition/negation: Peace/violence

The rights discourse engenders a situation where recognition involves negation (Veracini, 2008:369). Hence, Fisher (2008:3) rejects the simple dichotomy between recognition and non-recognition. ‘Recognition’ is central to liberalism, which seeks to accommodate difference and is characterised by apparent benevolence, ‘seeming openness [and] voracious encompassment’ (Povinelli, 2002:16). Rather than exclusion it is characterised by inclusion (and partial destruction) of difference: an ‘included-exclusion’ because the claims, values, knowledges and ways of knowing that test the limits of liberalism are subtly excised (Corntassel, 2008: 115; Brigg, 2010:411). Therefore, “liberalism is harmful not only when it fails to live up to its ideals, but when it approaches them” (Povinelli, 2002:13).

The consequence of liberal recognition/negation is a transformation of the crisis of liberal legitimacy into a ‘crisis of how to allow cultures a space within liberalism without rupturing its core frameworks’ (Hinkson & Altman, 2010: 24). In the context of cultural heritage and land claims, recognition displaces ‘the ‘burden of history’ from the ‘fact of expropriation to the character of the expropriated’.’(Lahn, 2007:136) This is evident in the Mabo High Court decision, which preserved Crown sovereignty and deferred resolution of the following fact: without the terra nullius doctrine no legal category exists by which British occupation could be considered legal under international law, making occupation illegal (Falk and Martin, 2007:34).

The ‘mobius strip’ of recognition/negation parallels the ‘strange doubleness’ of the coloniser’s gestures, which ‘embrace and reject violence at the same time’ (Veracini, 2008:365, emphasis original). Violent erasure was necessary to enable colonisation and was continually disavowed to preserve the fantasy of peaceful settlement. For example, Governor Arthur of Tasmania ‘oscillated wildly between expressions of concern for the Aborigines and military campaigns against them’ and ‘consistently sought to justify this violence in compassionate terms’ (Manderson, 2008: 227, 234). This violence is kept in tact post-Mabo. It follows that violent erasure of Indigenous sovereignty is necessary to preserve the fantasy of Crown sovereignty. Peace and war become indistinguishable (Mansfield, 2007:155). The war analogy is elaborated by Moreton-Robinson (2006:386) who argues that ‘politics is war by other means’. Benevolent recognition, then, is an attempt to make peace without having declared war, which is itself a tactic of war.

Can the subaltern speak? I: the judicio-political context

In the context of land claims, self-presentations (darstellen) are not possible because the subaltern cannot speak without being implicated by the “subject-effects, the inscriptions, found in colonial historiography” (Childs and Williams, 1997:163). For example, the image of the ‘natural man’ (later dubbed ‘noble savage’) underpins the liberal politico-philosophical creation story of the ‘state of nature’ to the ‘civil state’ (James, 1997:54). Indigenous and White identities are produced inter-subjectively – the tolerant liberal subject depends upon the traditional ‘Other’ to whom he dispenses recognition. However, this mutual entanglement is not acknowledged, making White identities transparent (Maggio, 2007:422). Furthermore, the subaltern cannot speak because the subaltern is hindered by the internalisation of discourses of culture loss (Smith, 2003:122). Indigenous knowledges are mediated through anthropologists, lawyers and judges and molded to meet the evidentiary requirements and epistemological terms of the court arena. To transgress these terms is to risk being unintelligible and thus unrecognisable (Andreotti, 2007:71). Such high stakes engender mimetic practices in an attempt to ‘pass’ as traditional (Smith, 2003:139).

Can the subaltern be heard? Negotiating the liberal impasse with resistance

The idea of collusion and resistance resituates the onus on speech to whether or not the subaltern can be heard when he/she/they speak. Povinelli (2002:3) argues that legal contexts such as native title generate an impasse. An impossible choice must be made between participation and non-participation, between enforced commensurability and forfeiting an opportunity for potential symbolic and material gain. Indigenous claimants are ‘called upon to performatively enact and overcome this impasse as the condition of recognition’ (ibid). Thus, caught in a double bind, Indigenous peoples can ‘neither be nor cease to be themselves’ (ibid). This statement encapsulates two distinct, though not incompatible, positions of collusion and resistance, which suggests that the court arena is not a totality. The Yolgnu of Blue Mud Bay native title claim illustrates this point.

In court, White law is both performed and enacted, whereas Yolgnu law (rom) is only performed. Rom cannot be heard on its own terms, instead it is ‘the object of discourse; it is explicated through the mediating discourse of examination and cross-examination’ (Morphy, 2007:33). This objectification and codification of Indigenous knowledge distances its holders from their knowledge and ways of knowing. For example, it denies the dynamism of local knowledge negotiation (Glaskin, 2007:60) and ‘epistemic openness’ (Merlin in Smith, 2003:136). Similarly, Yolgnu claimants’ desire to perform ceremony suggests that experiential knowledge is a valid way to acquire understanding and thus proof of rom. Therefore, participation involves epistemological violence, alienation from rom and the self.

However, Yolgnu tacitly resisted the totality and authority of White law by seeing performance as enactment and exploiting opportunities to demonstrate this fact. These interjections, if not disruptions, may have produced liminal moments between performance and enactment for the White participants. For example, the Yolgnu claimants cancelled a boat trip to visit a significant site mid-journey because, as they explained, the harsh weather was a sign that the ancestors were unhappy. However, during the Welcome to Country, although many White participants were physically displaced to the margins of the room, the judge was not (Morphy, 2007:9). Moreover, enactment or rom equates to sovereignty, which remained beyond the bounds of recognition. That is, although collusion (with native title) met resistance (of its terms), the outcome continued to hinge on judicial recognition – and this recognition remained a form of (mis)hearing the subaltern.

Can the subaltern speak? II: the rights discourse

Gyatri Spivak suggests pointing to the silence – the space of enunciation – rather than the enunciation itself, as the latter does not exist in any authentic sense (Childs & Williams, 1997). Land claims are one component of the rights discourse, which has come under increasing attack and defense. On the one hand it is criticised by those who polarise the practical and symbolic, arguing that the focus on rights has come at the cost of progress on ‘material issues’ such as violence and impoverishment. It has also pathologised Indigenous culture as the source of violence. On the other hand, rights are defended by those who refuse to see Indigenous peoples or culture as ‘the problem’ and instead attribute violence to the impacts of colonisation. Both ‘sides’ experience a moral duty and redemptive impulse to help Indigenous peoples whilst concealing the gulf between their worry and the object of their worry (Cowlishaw, 2003:107). The structure of public discourse silences those who cannot speak within the tug-of-war between the practical and symbolic. When the subaltern does attempt to speak she can only speak within these polarised terms. There is no third space that might allow the ‘Other’ to truly live (Butler in Youdell, 2012:152).

Whiteness as hidden standpoint

A persistent theme running throughout this essay is liberal subjectivities and moral sensibilities, which are maintained through a failure to systematically question hegemonic standpoints. The act of seeing, defining, representing and judging the Indigenous ‘Other’ entail ‘epistemological privilege’, which protects Whiteness and is enabled by it. Therefore Whiteness is both a context – a set of invisible White norms against which others are judged – and a privileged position imbued with disciplinary (discursive) and regulatory (structural) power (Moreton-Robinson, 2006:388). The two aspects are mutually reinforcing and can be seen in land claims where Indigenous people are not only subject to White legal criteria and norms, but also to White legal ‘authority to rule over the acceptability of Indigenous claims’ (Smith and Morphy, 2007:7). It produces deeply ironic reversals such as the onus on Indigenous people – not White people – to prove and justify their connection to place.

However, Whiteness as standpoint is transparent because it is erased of its racial character and elevated to a status of universality. It is not raced, accented or marked. It is a form of objectifying power. Indeed, Mabo is part of a wider discursive shift to the ‘post-racial’ where race is replaced with ‘ethnicity’ and ‘multiculturalism’ (Maddison & Brigg, 2011: 23). However, the post-racial is to the racial as the post-colonial is to the colonial (Goldberg, 1993). This heralds a new era of equality made possible by a mythologised break from the past and the belief that race can be legislatively (or scientifically/rhetorically) cast away (Youdell, 2012:144). This works to further conceal race and Whiteness[2].

Nicoll (2000:372) shows how courts deploy the third person passive voice in the oral/text distinction, relegating ‘Indigenous standpoints to ‘perspectives’’. She observes,

‘It is not that these men are intolerant. On the contrary, these men perform liberal tolerance precisely through respecting the perspective of others. As far as they are concerned, the coincidence of the passive voice and the straight, white middle-class male is just that—a coincidence. This ensures that the subject who arbitrates between the perspectives of different individuals or groups remains invisible.’ (2000:371, emphasis original)

When this ‘perspective-less’ standpoint is challenged, the possessive logic of patriarchal white sovereignty becomes apparent through discourses of security that frame challenges as a threat[3]. It reveals a subliminal white paranoia about dispossession of the nation, which is seen as a white possession (Moreton, Robinson, 2007:90).

I would argue that to ‘point to the silence’, as Gyatri Spivak suggests, is to reveal and engage with embodied standpoints (Childs and Williams, 1997). With this in mind, I began this research project with the intention of distilling differences between Indigenous and European political philosophies. I had hoped this would illuminate Indigenous sovereignty, which I see as critical to addressing injustice. I have experienced a problematic tension between analysing Indigenous difference and the process by which knowledge about the ‘Other’ (alterity) is produced. I attribute the discomfort I experienced in presenting my preliminary research to an insufficiently problematised standpoint.

Reading Nicoll’s (2000) work was revelatory for me. She states, ‘Indigenous sovereignty exists because I cannot know of what it consists; my epistemological artillery cannot penetrate it.’ (2000:370, emphasis original). In losing ‘perspective’ we give up the positional power to know the ‘Other’ and as Nicoll (2000:385, emphasis original) advises, ‘what you know will turn out to be less important than who you know and what you cannot know’.

Conclusion

Indigenous knowledges are not only subjugated but also produced to fit the discursive and legislative requirements of the court arena. Indigenous claimants are faced with an impasse between engaging with the court on its terms and rejecting these terms but forfeiting the potential benefits of recognition. Resistance is a possible ‘third space’ between engagement and disengagement, however it continues to hinge on liberal subjects’ ability to hear what is being said. Recognition entails negation, just as peace entails war, and is underpinned by the possessive logic of patriarchal white sovereignty. Liberal values and the apparent benevolence they entail make this process invisible. More broadly, the rights discourse risks reproducing forms of sovereign and disciplinary power, which Indigenous peoples seek to transcend.

In addition, the subaltern cannot speak within the judicio-political context, or within the rights discourse more generally, without changing the knowledge-power relations that constitute the subaltern in the first place. So we can ask the question, ‘Would the recognition of Indigenous sovereignty befall a similar fate of incorporation and destruction?’ Quite possibly, however this question is misleading. Indigenous sovereignty may defy liberal recognition because such an act leaves White epistemological privilege in tact. This suggests that Indigenous peoples’ demands will not be heard until Whiteness is raced and the ‘view from nowhere’ is revealed as a white standpoint.

References

Andreotti, V. (2007) An ethical engagement with the Other: Spivak’s ideas on education, Critical Literacy: Theories and Practices, 1(1): 69-79.

Bird-Rose, D. (2000) Dingo makes us human: life and land in an aboriginal Australian culture, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne.

Briggs, M. (2007) Biopolitics meet Terrapolitics: Political Ontologies and Governance in Settler-Colonial Australia, PhD Thesis, University of Queensland.

Brigg, M. (2010) Biopolitics meets Terrapolitics: Political Ontologies and Governance in Settler-Colonial Australia, Australian Journal of Political Science, 42(3): 403-417.

Childs, P. And Williams, P. (1997) An Introduction to Post-Colonial Theory, Prentice Hall, Hertforshire, Chapter 5: Spivak and the subaltern, pp. 157-184.

Corntassel, J. (2008) Towards Sustainable Self-Determination: Rethinking the Contemporary Indigenous-Rights Discourse, Alternatives, 33(1): 105-132.

Cowlishaw, G. (2003) Disappointing Indigenous People: Violence and the Refusal of Help, Public Culture, 15(1): 103-125.

Curthoys, Genovese, Reilly (2008) Rights and redemption: History, Law and Indigenous People, University of NSW Press, NSW.

Falk, P. and Martin, G. (2007) Misconstruing Indigenous sovereignty: Maintaining the fabric of Australian law, in Moreton-Robinson, Aileen ‘Sovereign Subjects: Indigenous Sovereignty Matters, Allen & Unwin, NSW.

Fisher, N. (2008) Out of Context: The liberalisation and appropriation of ‘customary’ law as assimilatory practice, ACRAWSA e-journal, 4(2): 2-15.

Foucault, M. (2003) Society must be defended: lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-76, Picador, New York.

Goldberg, D. (1993) Racist Culture: Philosophy and the Politics of Meaning, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

Glaskin, K. (2007) Claim, culture and effect: property relations and the native title process, in Smith, B. R and Morphy, F. ‘The Social Effects of Native Title: Recognition, Translation and Co-existance’, Australian National University Press, Canberra, pp. 59-77.

Hinkson, M. and Altman, J. (2010) Culture crisis: anthropology and politics in Aboriginal Australia, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney.

James, R. (1997) Rousseau’s Knot: The Entanglement of Liberal Democracy and Racism, in Cowlishaw, Gillian (Editor); Morris, Barry (Editor), ‘Race Matters: Indigenous Australians and ‘Our’ Society’, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, pp. 53-75.

Lahn, J. (2007) Native title and the Torres Strait: encompassment and recognition in the Central Islands, in Smith, B. R and Morphy, F. ‘The Social Effects of Native Title: Recognition, Translation and Co-existance’, Australian National University Press, Canberra, pp. 135-149.

Maddison, S. & Brigg, M. (2011) Unsettling the settler state: creativity and resistance in indigenous settler-state governance, Federation Press, NSW.

Maggio, J. (2007) “Can the subaltern be heard?” political theory, translation, representation, and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Alternatives, 32 (4): 419-443.

Manderson, D. (2008) Not Yet- Aboriginal People and the Deferral of the Rule of Law, ARENA Journal, 29(30): 219-272.

Mansfield, N. (2007) Under the Black Light: Derrida, War and Human Rights, Mosaic, 40(2): 151-164.

Moreton-Robinson, Aileen. (2006) Towards a New Research Agenda: Foucault, Whiteness and Indigenous Sovereignty, Journal of Sociology, 42(4): 383-395.

Moreton-Robinson, Aileen M. (2007) Writing off Indigenous Sovereignty: the discourse of security and patriarchal white sovereignty, in Moreton-Robinson, Aileen M. (Ed.) ‘Sovereign Subjects: Indigenous Sovereignty Matters’, Allen & Unwin, NSW, pp. 86-102.

Moreton-Robinson, Aileen M. (2004) The possessive logic of partiarchal white sovereignty: The High Court and the Yorta Yorta decision, Accessed on 2nd November 2012 at http://www.borderlands.net.au/vol3no2_2004/moreton_possessive.htm.

Morphy, F. (2007) Performing the Law: The Yolgnu of Blue Mud Bay meet the native title process, in Smith, B. R and Morphy, F. ‘The Social Effects of Native Title: Recognition, Translation and Co-Existance’, Australian National University Press, Canberra, pp. 31-57.

Nicoll, Fiona. (2000) Indigenous Sovereignty and the Violence of Perspective – a White Woman’s Coming Out Story, Australian Feminist Studies, 15(33): 369-386.

Povinelli, E. A. (2002) The Cunning of Recognition: Indigenous Alterities and the Making of Australian Multiculturalism, Duke University Press, United States of America.

Smith, B. R. (2003) ‘All Been Washed Away Now’: Traditions, Change and Indigenous Knowledge in a Queensland Aboriginal Land Claim, in Pottier, J., Bicker, A., and Sillitoe, P., ‘Negotiating Local Knowledge: power and identity in development’, Pluto Press, London.

Smith, B. R and Morphy, F. (2007) The Social Effects of Native Title: Recognition, Translation and Co-Existance, Australian National University Press, Canberra.

Smith, Linda. Tuhiwai (1999) Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, Zed Books, London.

Trigger, D and Asche, W. (2010) Christianity, culture change and the negotiation of rights in land and sea, The Australian Journal of Anthropology, 21(1):90-109.

Veracini, L. (2008) Settler Collective, Founding Violence and Disavowal: The Settler Colonial Situation, Journal of Intercultural Studies, 29(4): 363-379.

Watson, I. (2002) Aboriginal Law and the Sovereignty of Terra Nullius, Borderlands, Accessed 1st Nov 2012 at http://www.borderlands.net.au/vol1no2_2002/watson_laws.html

Youdell, D. (2011) Fabricating ‘Pacific Islander’: pedagogies of expropriation, return and resistance and other lessons from a ‘Multicultural Day’, Race, Ethnicity and Education, 15(2): 141-155.

[1] No page numbers accompanied Moreton-Robinson, 2004.

[2] The way I have separate ‘race’ and ‘Whiteness’ is indicative of the way in which Whiteness distances itself from race.

[3] The possessive logic of patriarchal white sovereignty also plays out in subtle ways such as the term ‘Indigenous Australians’ and phrases such as ‘our Indigenous people’.

0 notes

Text

Shedding light on my own Imaginary

“What is Aboriginality? Is it being tribal? Who is an Aboriginal? Is he or she someone who feels that other Aboriginals are somehow dirty, lazy, drunken, bludgers? Is an Aboriginal anyone who has some degree of blood in his or her veins and who has been demonstrably disadvantaged by that? Or is an Aboriginal someone who has had the reserve experience? Is Aboriginality institutionalised gutlessness, an acceptance of the label ‘the most powerless people on earth’?’ Or is Aboriginality when all the definitions have been exhausted a yearning for a different way of being, a wholeness that was presumed to have existed before 1776?

Irene Watson (Jordan, 1988: 114)

“As I am an Aborigine, I inhabit an Aboriginal body, and not a combination of features which may or may not cancel each other. Whatever language I speak, I speak an Aboriginal language, because a lot of Aboriginal people speak like me. How I speak, act and how I look are outcomes of a colonial history, and not a particular combination of traits from either side of the frontier”

Ian Anderson (2003: 51)

“The whole policy of Black Power in Australia is a policy of self-assertion, of self-identity”

Paul Coe (Stokes, 1997: 165)

“They came, They saw, They named, They claimed”

Linda Tuhiwai-Smith (Anderson, 2003: 22)

‘Orientalism’ or its ‘Australian’ equivalent, ‘Aboriginalism’, denies recognition of the ‘Aboriginal-as-subject’. The naming and labeling of the landscape, events and people by “explorers” is a case in point. The process is intimate in that the coloniser “produces the colonised as a fixed reality which is at once an ‘other’ and yet entirely knowable and visible” (Bhabha, 1983: 23) at the same time as “distancing himself…by not learning to know it on its own terms” (Sider, 1987: 12). That is, Indigenous-settler relations are marked by a “refusal to come close to or become familiar with the reality of indigenous experience” (Cowlishaw, 1998: 155). Binary categories are naturalised within colonial discourses to locate ‘non-indigenous’ at the opposite pole to ‘indigenous’. Paradoxically, whilst critiquing these binaries, I employ them throughout this essay, demonstrating the tensions embedded in language itself. Constructions of the “primitive”, “savage” or “spiritual other” is a reflection of settlers’ fears, aversions and desires, rather than Indigenous peoples realities. Thus I believe that stereotypic images of the ‘Other’ are self-serving myths used to legitimate frontier violence, dispossession, denial of citizenship rights, and so on. Langton (2009) suggests,

“The central problem is the failure of non-Aboriginals to comprehend us Aboriginal people, or to find the grounds for an understanding. Each policy – protection, assimilation, integration, self-management, self-determination and even, perhaps, reconciliation – can be seen as ways of avoiding understanding”.

Settler and Indigenous identities are mutually shaped in intimate engagement, attraction and opposition. Identities are (re)produced in multiple locations: criminal justice, welfare, the national politics of Mabo and land claims, the domains of tourism and art galleries, government bureaucracies, media and academia (Cowlishaw, 1997: 3). In this essay, I shall examine the contested nature of Aboriginalities amongst Aborigines; the way constructions based on descent or ‘blood’, cultural continuity and purification operate within Native Title; the dominant settler responses of denial and redemption and the way in which nationhood is reproduced through the discourse of “liberal multiculturalism” or in other words the re-appropriation of Indigenous-as-object through nationalist narratives. Finally, I shall explore the possibilities for transformation by exploiting the ambivalences within colonial discourses. Indigenous peoples have responded in multiple and creative ways to invasion and colonisation. Through a mixture of collusion and resistance, Indigenous peoples have historically challenged, and continue to disrupt colonial discourses.

Some worldviews assert that knowledge or ‘truth’ is not natural, timeless or universal, but produced, contingent, situated and particular: “not only is discourse always implicated in power, discourse is one of the “systems” through which power circulates” (Tuhiwai-Smith, 1999: 169). ‘Orientalism’ is synonymous to what Cowlishaw (1988: 87) terms ‘Aboriginalism’, where indigenous peoples are made in to ‘objects’ of knowledge, which gives material force to settlers’ representations. Michael Foucault refers to this phenomenon as “regimes of truth” (Tuhiwai-Smith, 1999: 166). Far from being passive recipients, Indigenous peoples actively shape, through both collusion and resistance, such “regimes of truth”. This material force has most obviously manifested as frontier violence and massacres, the forced removal of children from their families and entire peoples from their ancestral lands through reserves, missions and cattle stations, and the policies of “Protection”, “Segregation” and “Assimilation” (Dodson, 2003: 30). Paradoxically, these conditions “both give a people birth and simultaneously seek to take their lives” (Sider, 1987: 3). Settler identities and Indigenous peoples’ identities are co-constructed. Morris (1992: 80) argues that during the 19th century, images of Aboriginal people as wantonly violent and treacherous were used to create an atmosphere of ambivalence and uncertainty that rationalised settler violence, such as the ‘bushwack’ (killing sprees), satisfying the desire to eliminate the ‘Other’ and “restore a singular, straightforward reality”. Veracini (2008: 366) suggests that settlers constructed Indigenous peoples’ nomadism as “unsettled” and as an “intrusion” upon what became their own “indigenous” status. In policy discourse, Indigenous peoples remain a “problem” to be “solved” enabling an artificial disentanglement of settler-complicity in the trauma and injustices Indigenous peoples have suffered and continue to experience (Beckett, 1988: 2; Dodson, 2003: 27). European discourses constructed Indigenous peoples as indices to affirm settlers’ advanced condition along the evolutionists “Great Chain of Beings”, as abject referents to affirm settler superiority and as romanticised ‘other’ (Buchan, 2005: 47, Anderson, 2003; Dodson, 2003; Moreton-Robinson, 2003). Definitions of Aboriginality abound and whilst an Indigenous person is now officially classified by the government as self- and community-identified, non-Indigenous people and institutions continue to make “representational and aesthetic statements”, which Langton (2009) argues denies the “Aboriginal-as-subject”.

Aboriginality, in the sense it is known today, did not exist prior to British invasion (Maddison, 2009: 103). Indigenous peoples defined themselves according to language group and ‘clan’ or attachment to Country and Ancestor Beings who created the landscape, languages and Laws of existence (Graham, 1999; Rose, 2000). Social organisation such as ‘moiety’, ‘semi-moiety’ and skin further defined the ‘self’. Gender, sexuality and ability added to this diversity. Many Aboriginal people continue to identify in these ways. There is no single accepted definition of Indigeneity among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Indigeneity is “not a fixed thing, it is created from our histories…from the intersubjectivity of black and white in a dialogue” (Langton, 2009). Hollingsworth (1992: 140) identifies three broad discourses on Aboriginality: biological descent (‘blood’), cultural persistence and political resistance. Defining Aboriginality is a “source of political struggle both within Aboriginal communities and between them and the Australian state” (Stokes, 1997: 169). “Protection” policies operated upon racially prejudiced and essentialised beliefs of ‘degrees of blood’ as part of a sustained effort to assimilate the Aboriginal ‘population’ (Dodson, 2003: 35). Biological determinism persists as a tool of exclusion, for example in 1998 Returned Services League (RSL) President Brigadier Garland called for ‘genetic proof’ of a persons’ Aboriginality to determine membership (Hollingsworth, 1992: 142). Aboriginal people also employ notions of ‘blood’ as determining Aboriginality, such as the label “yellafella” implies, and in determining access to benefits or royalties (ibid). Huggins (2003: 63) argues that Aboriginality is more than genetic inheritance, a discourse she attributes to anthropology, but is contingent upon social practice and an embeddedness within kinship. Hollingsworth (1992: 145) argues that any claim to a set of universal traits that define Aboriginality is ultimately exclusive. However, Moreton-Robinson (2003: 32) argues that for Indigenous peoples, land is the essence of belonging and that the view of ‘self’ as not unitary nor fixed is situated in a ‘western’ epistemology that opposes (and yet employs) essentialism. Both Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous people ‘essentialise’ Aboriginality and Aboriginal culture, however their motivations and consequences are quite different. Most non-Aboriginal people continue to assess Aboriginality based on skin colour and the practice of a ‘traditional’ lifestyle (Perkins, 2003: 100) which fails to recognise the heterogeneity and dynamism of Indigenous being.

Native title and ‘land rights’ regimes re-entrench traditionalised stereotypes based on cultural continuity or fixity and a ‘primitive-modern’ binary, creating new barriers to the recognition of identities. ‘Real’ Aboriginality is recognised as what settlers are not, and thus refuses to acknowledge the realities of colonial domination, interculturalism and historical change (Cowlishaw, 1997: 6; Maddison, 2009: 106). Dispossession was made possible by settlers’ engagement in the “linguistic and conceptual representations” that “affirmed settler experiences and interests” (Buchan, 2005: 3). Aboriginal peoples were seen as lacking governance or “polity”, “social organisation”, “land ownership” or “property” (ibid). Whilst overturning “terra nullius”, the Mabo High Court decision suppressed questions regarding the legal validity and legitimacy of Australia’s claim to sovereignty (Foley, 2007: 133). The legislation effectively re-dispossesses Indigenous peoples who do not fit settlers’ notions of Aboriginality, including urban, rural and various remote communities. As Hollingsworth (1992: 143) notes, “for certain Aboriginal communities who display or can mobilise the officially-sanctioned trappings of authenticity, their claim as bearers of the ‘worlds oldest living culture’ is relatively straightforward”. However, even those who manage to achieve claimant status are ‘caught’ by the “prison knowledge” of settler sensibilities (Sackett, 1991: 241; Dodson, 2003: 27). Land claims inspire in subaltern subjects not a desire to identify with their colonisers (as Franz Fanon suggests), but with the judges’ imagined model of Aboriginality, “a form of pure cultural difference untouched by and not oriented to state colonial history” (Povinelli, 2002: 162; Maddison, 2009: 105). At the same time they must “ghost this being for the nation so as to not have their desires for some economic certainty in their lives appear opportunistic” (Povinelli, 2002: 8). As Linda Tuhiwai-Smith (1999: 106) observes, “At the heart of such a view of authenticity is a belief that indigenous cultures cannot change, cannot recreate themselves and still claim to be indigenous. Nor can they be complicated, internally diverse or contradictory. Only the West has that privilege”. The Yorta Yorta people were the first group subject to this dehistoricised ‘recognition’ of their status as Traditional Owners, which denied the “complex intercultural realities” at the very moment indigenous-settler identities are entangled and co-constructed. Aboriginal people should not be limited by the past, nor denied the ability to reclaim it. As Dodson (2003: 40) eloquently puts it, “the past and the present and the future do not fall into distinct linear categories. The past cannot be limiting because we are always transforming it. In all expressions of our Aboriginality, we repossess our past, and ourselves”.

Settlers continue to produce and inherit images of Aboriginality that accord with biological determinism and cultural continuity. Threatening or non-threatening images are deployed to accommodate denialist and redemptive strategies respectively, which then reify new national identities. However it would be simplistic to suggest that only denialist strategies treat Aboriginal peoples as a threat. Birch (2003: 148) illustrates how a rural town council’s proposed ‘name restoration’ of tourist landmarks elicited hostile responses from locals who sought to protect the “memory”, “honour” and “sacrifice” of “pioneering forefathers”. Some local whites dismissed the Aboriginal community as a “cultureless remnant” (ibid). John Howard’ s use of “black armband” history and refusal to offer an apology is emblematic of politically conservative views still salient (Chandra-Shekeran, 1998: 131). However, the incorporative approach to settler-indigenous relations is equally as problematic. In Mabo the High Court used the language of shame, regret, embeddedness and implication in tandem with the “good that the common law and liberal democratic state was [and] sought to be” (Povinelli, 1998b: 160). Public commentators referred to a “redeemed social body, to an equitable society, and to a tolerant nonracist white subject” (ibid, 163). ‘Cultural appropriation’, the incorporation of metonyms (such as boomerang, didgeridu, Uluru or ‘deep history’) within nationalist narratives, sustains “an imagined community in Australia that now pride[s] itself on being ‘multicultural’ and ‘tolerant’” (Langton, 2003: 82; Birch, 2003: 151; Anderson, 2003: 46). Moreton-Robinson argues this is a strategy to “achieve the unattainable imperative of becoming Indigenous in order to erase unbelonging” (2003: 30). As Zizek (1997: 44) argues, “Multiculturalism is a disavowed, inverted, self-referential form of racism…it ‘respects’ the Other’s identity, conceiving the Other as a self-enclosed ‘authentic’ community towards which he, the multiculturalist, maintains a distance rendered possible by his privileged universal position…respect for the Other’s specificity is the very form of asserting one’s own superiority”. Liberal-thinkers position themselves as anti-racist without problemitising the institutions and processes that give rise to racialised representations and marginalisation (Cowlishaw, 1997: 3). This redemptive strategy creates the ‘Other’ whilst Indigenous peoples are silenced as their imagined world is being appropriated and their realities are ignored.

“The ‘authority’ of colonial discourse depends crucially on its location in narcissism and the Imaginary” (Bhabha, 1983: 32). Social Darwinism attributes meaning to human progress and ontology according to a linear temporality – “primitive” exists in contradistinction to “modernity”. Romanticised images of indigenous peoples have long been a way of affirming European identities and facilitating their own interests. The “primitive other” is something to disdain and/or desire; a phobia and/or fetish (ibid: 25). The ‘primitive-modern’ binary is invoked as a medium through which “political critiques of culture and human nature are articulated” (Lattas, 1992: 46). For example, in the mid-18th century French intellectuals used the discourse of ‘noble hunter-gatherers’ to critique the status quo and facilitate the French Revolution (Sackett, 1991: 240). This social Darwinian trope has pervasive usage in contemporary parlance. For example, the need to adopt low-consumption lifestyles is labeled “stone age” by opponents to environmental justice. “Primitive” is used to describe behaviour that is repetitive, ritualistic and unthinking and is synonymous with “backwardness” (Lattas, 1992: 47). Mass culture is criticised as having “regressed” to a “primordial instinctual past” due to a perceived departure from the “individuated and reflective subject” (ibid). Lattas (1992: 50) argues that public intellectuals “create and require a sense of spiritual crisis in order to create a need for personal and national redemption”. Paradoxically, ‘Aboriginal culture’ is then mined in order to fill a perceived spiritual vacuum through discovering the ‘Dreaming’ or the unique relationships Aboriginal peoples have with nature (McIntosh, 2002: 23; Rolls, 2000: 150). This sentiment has inspired novels such as Marlo Morgan’s Mutant Messages Down Under, to which Indigenous peoples, upon whom the book is ostensibly based, have protested (Povinelli, 1988b: 10). Further, the construction of Indigenous peoples as “original stewards” leads conservationists to assume Aboriginal people will respond in particular ways to ‘development’ projects. When they do not, (often because there is no alternative to ameliorating the exigencies of the colonial legacy of poverty) they are viewed as a “disappointment”, as occurred in the Kakadu uranium and Daintree road cases (Sackett, 1991: 242). Cowlishaw (1998: 156) illustrates the process by which white officials became ‘ventriloquists’ of Rembarrnga people’s “wishes” producing “communities” who conformed to white officials’ visions of progress. In seeking to counter anti-self-determination rhetoric, liberals muted their fears of failure should they be seen as “mistaken about Aborigines’ desires or abilities” (ibid). When Indigenous peoples fail to conform to such images they run the risk of dismissal or, as is common, being labeled “engineers” of their own “failure”. Imagined portrayals are used as a sounding board for settler identities, whether it is to affirm ones superiority or critique/ameliorate the crises of modernity.

Indigenous peoples responses are crucial to understanding subjectivities and how they form. Whilst settler discourses of the ‘Other’ may be internalised, Aboriginal peoples have also constructed politicised identities. However, non-Aboriginal people (myself included) seldom discern the subtleties of resistance and it is largely ignored by disciplines such as anthropology (Cowlishaw, 1988: 88). Moreton-Robinson (2003: 128) suggests,

“There is no single, fixed or monolithic form of Indigenous resistance: rather than simply being a matter of overtly defiant behaviour, resistance is…multifaceted, visible and invisible, conscious and unconscious, explicit and covert, intentional and unintentional”.

Nor is silence necessarily subservience, for example, Denise Groves (Palmer & Grovers, 2000: 36) describes Aboriginal women ‘domestics’ who subtly disrupted the ‘slave/Master’ relationship by only talking when granted permission. Paradoxically, “overcoming domination involves engaging with domination to struggle against it”, thus ‘choice’ is not the essence of resistance (Sider, 1987: 7). Indigenous writers, academics and artists are often pressured to compromise their work to satisfy publisher or audience preferences for stereotypic and non-threatening discourses (Perkins, 2003: 102). One may, for example, reject the (loaded) label ‘Aboriginal artist’ or one may work within colonial discourses in order to generate a ‘counter discourse’ (Ariss, 1988: 132). For example, Badtjala woman Fiona Foley engaged lawyers when her Witnessing to Silences, commissioned by Brisbane’s Magistrates Court, was threatened with censure (Foley, 2006: 23).

Furthermore, colonial discourses exhibit incompleteness, instability and ambivalence, reflected in the way stereotypes “must be anxiously repeated” (Bhaba, 1983: 18). These ‘cracks’ are cleverly exploited as sites of contestation and transformation (Palmer & Groves, 2000: 36). Songs, dramatisations and inversions comprise a rich tapestry of private or ‘hidden transcripts’ (Furniss, 2006: 183). I was humoured by a story of an Aboriginal woman in a rural township who removed her clothes in public then screamed as (white, male) police officers attempted to seize her, causing the police to hastily retreat (Cowlishaw, 1988b: 98). Denise Groves (Palmer & Groves, 2000: 34) describes an Aboriginal academic who ‘plays up’ to non-Aboriginal students’ expectations that “Indigenous people who live in urban settings have lost their culture and become modernists” and then disrupts this by beginning a lecture in Nyungar. ‘Non-violent’ Aboriginal resistance takes two distinct forms: demand for equal citizenship emphasising ‘similarities’ and demands for land rights, self-determination and sovereignty emphasising ‘difference’ (Stokes, 1997: 162). In short, Indigenous peoples are either treated as “equal” but also as identical (resulting in assimilation) or as different (but not according to their own terms or conceptual systems) (Patton, 1995: 87). Murphy (2000: 30) argues that Aboriginal peoples’ representations of Aboriginality through, for example, the Tent Embassy and Native Title, constitute “false radicalism” and “undermine the very status upon which we articulate our difference because we place ourselves within their paradigms of ‘object’ and ‘other’ ”. Similarly, Taiaiake Alfred (2009: 23) argues that ‘sovereignty’ is “an exclusively European discourse” which has “limited the ways in which we are able to think, suggesting always a conceptual and definitional problem centred on the accommodation of indigenous peoples within a “legitimate” framework of settler state governance” (ibid). Resistances are threatened by settlers’ desires for an identical (equal) vs. ‘pure’ (different) indigenous subject (Kowal, 2009: 236). However there are also numerous indigenous critiques of how ‘Aboriginality’ is expressed through resistance. But perhaps it is within these discursive ‘cracks’ that lie possibilities for insight and transformation.

In seeking to expose the imaginary of colonial discourses and recognise ‘Aboriginal people as Aboriginal people’ (Murphy, 2000: 35) there remains the risk of missing the point that Aboriginality is contested among Indigenous peoples. ‘Aboriginal-as-subject’ (Langton, 2009) is necessarily diverse because colonial discourses have not been uniform or fixed, nor have indigenous peoples’ responses. How do settlers and the settler-state engage with this multiplicity and complexity? Is it even possible for the latter to do so? The state, with its own ideological and philosophical foundations has associated itself with certain expressions of Indigeneity that do not challenge the hegemony of liberal democracy. Throughout this essay I have attempted to convey not only what (negative/positive) stereotypes colonial discourse produces but also “an understanding of the processes of subjectification made possible (and plausible) through stereotypic discourse” (Bhaba, 1983:18, original emphasis). If identities are entangled then won’t an ‘entangled dialogue’ be necessary in order to transform the ‘entanglement’? Who will be entitled to ‘speak for’ or re-present Aboriginalities and settler identities? Should only “self presentations” be possible? Is there a role for settlers in re-presenting Aboriginalities with or without Aboriginal peoples’ involvement? How can non-Indigenous people disrupt colonial discourses? Moreover, how do we become critically aware of the way in which settlers’ desires, interests and identities underpin the Aboriginalist discourse? When we are asked to describe what things make up our own culture and identity, do we go blank, puzzled, confused? Denise Groves (Palmer & Groves, 2000: 37) states,

“Being constructed as white you are both positioned as everything and nothing”.

Although I consider myself as ‘subaltern’ in some ways (and as ‘oppressor’ in others) I only recently came upon the idea that ‘whiteness’ is invisible to those upon whom it confers privilege. If we cannot see the entanglement of identities, then we cannot begin to transform Indigenous-settler relations. Further, how do we go about this when for the most part “Australians do not know and relate to Aboriginal people. They relate to stories told by former colonists” (Langton, 1993: 33) or the media or academia…? And when the potential for misunderstanding is so great as Cowlishaw illustrates in her analysis of “community” meetings between state officials and Rembarrnga. How can we overcome this solipsism? To what extent must settlers become other than what we are and other than how we know, in order to see Aboriginal peoples as “truly other, something capable of being not merely an imperfect state of oneself” (Todorov in Patton, 1985: 42)… or an idealised state? Kaplan (Langton, 1993: 25) suggests, “We can only enter from where we stand, unless we want simply to mimic those we aim to know about. Mimicry…is not knowledge”. In Singing the Land, Signing the Land Helen Watson (1989: 8) observes,

“the process of mediation between two ways of knowing inevitably involves transformation”.

And I wonder, what does this mediation look like, where does it take place, how does power operate, what does it lead to?

References

Anderson, Ian. (2003) ‘Introduction: the Aboriginal critique of colonial knowing’ in M. Grossman, A. Moreton-Robinson, I. Anderson and M. Langton (eds) Blacklines : contemporary critical writing by indigenous Australians. Carlton, Vic., Melbourne University Press, pp.17-24.

Anderson, Ian (2003) ‘Black Bit White Bit’ in M. Grossman, A. Moreton-Robinson, I. Anderson and M. Langton (eds) Blacklines : contemporary critical writing by indigenous Australians. Carlton, Vic., Melbourne University Press, pp. 43-51.

Ariss, R. (1988) ‘Writing black: the construction of an Aboriginal discourse’ in Beckett, J. R., Past and present: The construction of Aboriginality, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra.

Bhabha, Homi (1983) ‘The Other Question’, Screen, 24 (6), pp. 18-36.

Birch, Tony (2003) ‘‘Nothing has changed’: The making and unmaking of Koori culture’, in M. Grossman, A. Moreton-Robinson, I. Anderson and M. Langton (eds) Blacklines: Contemporary Critical Writing by Indigenous Australians, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, pp. 145-158.

Cowlishaw, G and Morris, B. (1997) ‘Race matters: indigenous Australians and ‘our’ society’, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra.

Cowlishaw, G. (1998a). “Erasing culture and race: practising ‘self-determination’.” Oceania 68(3): 145-170.

Cowlishaw, G. (1988b) ‘The materials for identity construction���, in Beckett, J. R., 1988. Past and Present: The Construction of Aboriginality, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, pp. 87-107.

Chandra-Shekeran, S. (1998) ‘Challenging the fiction of the nation in the ‘Reconciliation’ texts of Mabo and Bringing Them Home’, The Australian Feminist Law Journal, Vol. 11, pp. 107-133.

Dodson, Mick (2003) ‘The End in the Beginning: Re(de)finding Aboriginality’ in M. Grossman, A. Moreton-Robinson, I. Anderson and M. Langton (eds) Blacklines: Contemporary Critical Writing by Indigenous Australians, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, pp. 25-42.

Beckett, J. (1988) “Aboriginality, Citizenship & Nation State.” Social Analysis 24(December): 3-18.

Buchan, B. (2005) “The Empire of Political Thought: The Language of Civilisation and Perceptions of Indigenous Government.” History of the Human Sciences 18(2): 1-22.

Foley, Fiona (2006) ‘The art of politics the politics of art: the place of indigenous contemporary art’, Keeaira Press, Southport Qld.

Foley, Gary. (2007) The Australian Labor Party and the Native Title Act. Om Sovereign Subjects: Indigenous Sovereignty Matters. A. Moreton-Robinson et. al (eds). Crows Nest, NSW, Allen & Unwin: 118-139

Furniss, E. (2006) ‘Challenging the myth of indigenous peoples’ ‘last stand’ in Canada and Australia: public discourse and the conditions of silence’ in Coombes, Annie. E. Rethinking Settler Colonialism: history and memory in Australia, Canada, Aotearoa New Zealand and South Africa, Manchester University Press, New York, pp. 172-191.

Graham, M. (1999). “Some thoughts about the philosophical Underpinnings of Aboriginal Worldviews.” Worldviews: Environment, Culture, Religion 3(2): 105-118.

Gray, G. (1998). From Nomadism to Citizenship: A P Elkin and Aboriginal Advancement. Citizenship and indigenous Australians: changing conceptions and possibilities. N. Peterson and W. Sanders. Cambridge; Melbourne Cambridge University Press: 55-78.

Hollingsworth, D. (1992) ‘Discourses on Aboriginality and the Politics of Identity in Urban Australia’, Oceania 63: 137-155.

Huggins, Jackie (2003) ‘Always was always will be’ in M. Grossman, A. Moreton-Robinson, I. Anderson and M. Langton (eds) Blacklines: Contemporary Critical Writing by Indigenous Australians, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, pp. 60-65.

Jordan, D. F. (1988) ‘Aboriginal identity: uses of the past, problems for the future?’, in Beckett, J. R., Past and Present: The Construction of Aboriginality, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra.

Kowal, E. (2009) “Of Transgression, Purification and Indigenous Scholarship.” The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 10(3): 231-238

Lattas, A. (1992) ‘Primitivism, Nationalism and Individualism in Australian Popular Culture’, pp. 45-58 in B. Attwood and J. Arnold (eds) Power, Knowledge and Aborigines. Bundoora: La Trobe University Press.

Langton, Marcia. (1993) ‘Well, I heard it on the radio and I saw it on the television … : an essay for the Australian Film Commission on the politics and aesthetics of filmmaking by and about Aboriginal people and things’, Australian Film Commission, Sydney.

Langton, Marcia. (2009) ‘Aboriginal Art and Film: The Politics of Representation’, Rouge Press Archive, (http://www.rouge.com.au/index.html)

Lattas, A. (1992) ‘Primitivism, Nationalism and Individualism in Australian Popular Culture’, pp. 45-58 in B. Attwood and J. Arnold (eds) Power, Knowledge and Aborigines. Bundoora: La Trobe University Press

Maddison, S. (2009) Black politics: Inside the complexity of Aboriginal political culture. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

McIntosh, Ian, Marcus Colchester, et al. (2002) ‘Defining Oneself and Being Defined as, Indigenous’ Anthropology Today 18: 23-24.

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2003) ‘I Still Call Australia Home: Indigenous belonging and place in a White Postcolonising Society’, in Ahmed, Sara, Castaneda, Fortier, Anne-Marie, Sheller, Mimi (eds.), Uprootings/Regroundings: Questions of Home and Migration, New York: Berg Publishers, 2003, ch.1 pp. 23-40.

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2003) ‘Introduction: resistance, recovery and revitalisation’ in M. Grossman, A. Moreton-Robinson, I. Anderson and M. Langton (eds) Blacklines : contemporary critical writing by indigenous Australians. Carlton, Vic., Melbourne University Press, pp. 127-131.

Morris, B. (1992) ‘Frontier Colonialism as a culture of terror’, Journal of Australian Studies, 16 (35), pp. 72-87.

Murphy, L. (2000) ‘Aboriginal Deaths in Custody’. In Who’s Afraid of the Dark: Australia’s administration in Aboriginal Affairs, MPA Thesis, Centre for Public Administration University of Queensland. Available at http://eprint.uq.edu.au/archive/00000478/.

Palmer, D. and D. Groves (2000) ‘A Dialogue on Identity, Intersubjectivity and Ambivalence’ , Balayi: Culture, Law and Colonialism 1(2): 19-38 .

Patton, P. (1995). “Mabo and Australian Society: Towards a Postmodern Republic.” The Australian Journal of Anthropology 6(1 & 2): 83-94.

Perkins, Hetti (2003) ‘Seeing and seaming in: contemporary Aboriginal art’ in M. Grossman, A. Moreton-Robinson, I. Anderson and M. Langton (eds) Blacklines: Contemporary Critical Writing by Indigenous Australians, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, pp. 97-103.

Povinelli, Elizabeth, A. (2002) ‘The cunning of recognition : indigenous alterities and the making of Australian multiculturalism’, Duke University Press, Durham.

Povinelli, Elizabeth, A. (1998a) ‘The Cunning of Recognition – real being and Aboriginal recognition in settler Australia’, The Australian Feminist Law Journal, Vol. 11, pp. 3-27.

Povinelli, Elizabeth, A. (1998b) ‘The State of Shame: Australian Multiculturalism and the Crisis of Indigenous Citizenship’, Critical Inquiry, 24 (2), pp. 575-610.

Rose, D. B. (2000) Dingo Makes Us Human: Life and Land in an Aboriginal Australian Culture.

Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Sackett, L. (1991). “Promoting Primitivism: conservationist depictions of Aboriginal Australians.” The Australian Journal of Anthropology 2(2): 233…

Sider, G. (1987). “When Parrots Learn to Talk, and Why They Can’t: Domination, Deception, and Self-Deception in Indian-White Relations.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 29(1): 3-23.

Stokes, G. (1997). Citizenship and Aboriginality: two conceptions of identity in Aboriginal political thought. The politics of identity in Australia. G. Stokes. Cambridge, England; New York, Cambridge University Press: 158-171.

Tuhiwai-Smith, Linda (1999) ‘Decolonizing methodologies : research and indigenous peoples’, Zed Books, London.

Veracini, L. (2008). “Settler Collective, Founding Violence and Disavowal: The Settler Colonial Situation.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 29(4): 363-379.

Watson, H., D. W. Chambers et. al. (1989). Singing the land, signing the land: a portfolio of exhibits. Geelong, Vic., Deakin University Open Campus Program with Deakin University Press. Exhibit 1

Zizek, S. (1997), ‘Multiculturalism, or, the Cultural Logic of Multinational Capitalism’, New Left Review, Vol. 255, pp. 28-51.

0 notes