This blog consists of exhibition reviews and further thoughts arrived at by experiencing art in a cube flattened by the internet. These reflections of artworks and excerpts take into special consideration how art and art-spaces are changing in the Art space as it becomes submerged in our advancing digital/technological world. To better understand the Cube on the Net, please scroll all the way down as it all starts from Square One.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Invitation Artist

August 18, 2021

Link to Exhibition: https://artspaces.kunstmatrix.com/en/exhibition/7574217/ft%E6%B0%B4%E5%A2%A8-featuring-inkart

“FT.水墨” is a virtual exhibition hosted on the virtual gallery platform, Kunstmatrix. The original Chinese title of this exhibition translates directly to “Featuring Ink-art”. This space is a collaborative display of the works of three artists: Guo Jinping, Lu Haowei, and Chen Yunyi - all who are students trained by the National Taiwan University of Arts and the Institute of National Taiwan Normal University. Following a prompt to reconsider the premises and implications of their classic ink medium, the works of these artists reflect three developments of their traditional practice in ways that are personally meaningful to themselves.

Before looking further into the art, it is probably most productive to grasp an introductory understanding of the significance in ink-art in relation to the originating culture of both the art medium and the artists. In traditional Chinese art-making (especially in the case of ink-art), the characteristics and limitations of the [medium/material] itself will directly become the characteristics of the artistic expression. However, there has been a slight shift in this thinking as now the medium is welcomed as an “outsider” or guest that has been “invited” to participate in the creation of art. “The master has always been the artist's idea. This is the concept of ft. ink and wash.” As we compare the roles in ink-art making to the roles of a house master and a guest, then it is also in the viewer’s best interest to recognize how those who fill these roles are treated and how they are expected to act according to cultural courtesy. In Chinese culture - the master of the house/ the host accompanies the guest throughout their visit during the entire duration, they await their visitor’s arrival and welcome them in from perhaps even beyond the front door, and they escort their guests’ departure attentively. As for the guests, they are treated with great kindness and respect and are encouraged to feel at home in the hosts’ home. Thus, as the art medium is considered as a “guest”, the material existence of this medium has become personified and given a great deal of symbolic significance in cultural context. As put in the exhibition’s description, “[the medium has] history, context, and sentiment. In many cases, what kind of [medium] artists use is not just because of its material characteristics, but the symbolism behind it”.

With that information in mind, we can then appreciate the three artists’ creative manifestations in how they attempt to challenge and re-vision the potential in this master-guest relationship between the artist and the ink medium. The first artist, Guo, works with a style of colour separation (that resembles printing) to depict originally colorful objects, recognizing the beauty within industrial images through depictions by traditional ink. The second artist, Lu, replaces the traditional tool and surface of ink pens and rice paper with spray guns (meant for colouring figures/models) and modern illustration paper. Through this approach, Lu “[reflects on his] experience of life, but also [alludes to] the special feelings of Eastern culture”. Finally, the third artist, Chen, alternatively makes her explorations by looking at the composition and visual qualities of the “image” of ink-art rather than focusing on the medium itself. The result reflects a collaborative effort of fiction and reality, realism and abstraction, contemplating the comparison between ink-art’s innate beauty and its rationality.

Also, the virtual exhibition of “FT.水墨” is a prime example of how tradition is meeting the modern not only in its conceptual prompt, but also through how it is sharing culture in a way that could not be achieved until relatively recently. As the context, production, and curation of the artworks in this exhibition is visibly Asia-focused, it would be unlikely for this work to reach the audience it has without its digital platform. Even if we put aside the question of reach, virtual galleries spaces such as the ones provided on Kunstmatrix help to overcome the issue of inaccessibility and scarce-opportunity to share artwork in the first place. “FT.水墨” exemplifies how artists can access these sharing potentials even when they are still students. This kind of self-serve platform also allows the artist to retain some power in how they choose to present their work, just as how the curator of this exhibition has chosen this specific template for a virtual gallery, one with large ceiling-height windows and a bench spot to rest - yet no doors.

“Ft.水墨 Featuring INKART - 3D Virtual Exhibition by 晴山藝術 IMAVISION GALLERY.” www.kunstmatrix.com. Accessed August 18, 2021. https://artspaces.kunstmatrix.com/en/exhibition/7574217/ft%E6%B0%B4%E5%A2%A8-featuring-inkart.

0 notes

Text

Watching the Night Watch

August 18, 2021

Link to Exhibition: https://beleefdenachtwacht.nl/en

“Experience the Night Watch” is a virtual exhibition presented by The Rijksmuseum in collaboration with the NTR TV channel. This exhibition makes available to the audience a new heightened way to experience how we perceive art. Through a digital platform that is interactive for each visitor of the site, this project revisits the masterful and traditional painting, “The Night Watch” by Rembrandt van Rijn in a way that feels almost overly thorough. Some zooming commands of this exhibition delve in so closely that we can see the painted textures of the figures’ clothing as well as the chipping of paint which set a reminder of the Night Watch’s physically. This kind of viewing would not be possible in a regular gallery space.

In this exhibition, the user is able to click through points on the screen that triggers a narrative guide in explaining the Night Watch. While touring the painting and clicking at various points of interest, the viewer essentially pauses at the detailed elements of the painting - suddenly, this makes the painting feel as if it has become “larger” in scale than it actually is and more informationally packed than what we thought we could see. Rather than pausing for a few contemplative moments to stare at different artworks in a physical gallery space, this exhibition has presented the single painting as a gallery of its details. And as the usual gallery guide is replaced by the virtually recorded narrator triggered by certain user actions, the automated movements of the website provide us with a perceived sense of “super-vision”, as we learn about each detail of the Night Watch the screen shows us exactly what we should be focusing on and how we should be looking at this focal-point. For example, one path that a user can follow is to click on “Composition” then “Depth”. Through this path, the screen zooms in and starts scrolling horizontally across the painting from left to right, then leftwards-down, then upwards and it then zooms even closer onto the painting with the men in the background in frame (i.e. where the man in the top hat is). Throughout this process, the exhibition not only shows me what to see but how to see it and how long to look at it for. It manipulated our eyes into seeing often overlooked intentions of an artist such as the symmetry and parallel lines found in the composition of the painting. Once it was made apparent to me that there was suggestive lines that jetted out from a central point, the painting suddenly felt almost explosive.

In this exhibition, the narrative guide becomes rather integral and necessary in the full understanding of the painting, especially considering the high amount of non-fictional context that has been represented in the Night Watch. For example, by clicking into the “who is who?” section of the website, the screen presents an indexed layer to the painting that directly names (or gives a role) to almost every single figure in the painting. To the average audience member, this painting is no longer just a composition of random symbolic figures, but within this painting exists portraits that hold documentative value. With a single click, I now know that the man in the feathered hat holding a flag is Jan Visscher Cornelissen, and I am not just assuming that the man in the center is the most powerful but I know definitely that he is - and that his name, Frans Bannick Cocq is listed in the shield at the top right corner of the painting and that it is in fact spelled wrong and on purpose. Furthermore, there is an atmosphere that is created in this digital exhibition as the sounds aid the viewers in situating themselves in their imaginative perception of the painting’s setting. To an extent, there is a subtle sense that while we are viewing the Night Watch as a painting we are unknowingly and gradually slipping into the scene.

“Beleef De Nachtwacht.” Experience the Nightwatch, January 31, 2019. https://beleefdenachtwacht.nl/en.

0 notes

Text

One Does Not Stare on the Stairs

August 18, 2021

Link to Exhibition: https://www.historymuseum.ca/morningstar/explore/?showhs=0

The Morning Star is a dome-shaped mural piece residing above the staircase rising from the River Salon at the end of the Grand Hall in the Canadian Museum of History in Ottawa. Painted by Indigenous artist, Alex Janvier, the Morning Star’s name is drawn from the Indigenous Peoples’ traditional practice in using the morning star as a guide light in the early and dark mornings of winter; “They would leave camp break at maybe four o clock in the morning and head in some direction, and, according to the stars in the sky, and especially that one, they pretty well have an idea of the direction that they’re going to”.

In terms of the composition, the Morning Star clearly distinguishes a ring within a circle and four equal quadrants sliced by perpendicular lines; the Yellow Quadrant, the Blue Quadrant, the Red Quadrant, and the White Quadrant. In this order, these sections represent a time before the arrival of Europeans, a time of weakening of Indigenous Cultures, a time of struggle and affirmation of Indigenous beliefs and practices, and a time of healing and reconciliation. There are furthermore various symbols and layers to the mural that represent Indigenous values and traditions. In summary, it is a “commentary of 500 years of relations between aboriginal and non-aboriginal people in Canada.”

On the Canadian Museum of History’s website, there is a virtual exhibition of this mural piece that provides unique advantages in relation to the viewing potential of the Morning Star, including the addition of short interviewee clips and photographs linked to particularly relevant points of the mural. While some of these clips provide valuable, informational and descriptive explanations regarding the concept and visual composition of the Morning Star, there are also some videos that add documentative and experiential value. Particularly, two of my favourite clips are the ones titled “The first brush stroke” which shows the artist climbing up to the dome and leaving the first mark of red paint onto the white surface of the ceiling, and “Signing the completed work” in which Janvier is seen completing the mural with his last stroke of a signature onto a similarly red reaction of the Morning Star. The process of exploring this artwork through a virtual exhibition has allowed me to stare and inquire about something that is in reality placed in a location of liminal movement and minimal pausing. Contrary to what may be seen on the website, the Morning is not eye level and flat on a wall, but it is on the surface of a dome on the ceiling - it is in a space that quite literally results in its significance “going over our heads”. While this is the case, this placement can also feel rather poetic as it serves as a gentle reminder that comes as goes as the people do and it stays as a constant in a place that is visible yet often unseen (or not looked at.

On the other hand, the virtual platform that houses the Morning Star exhibition opens up a way of viewing the mural that cannot be observed in real life; as the user clicks to the right or left of the circle, the Morning Star spins in that direction at a rather quick pace. This perspective that is only accessible through my screen makes me suddenly self-conscious in the sense of realizing that the mural is the constant; I (we) are only temporary figures which move in relation to the Morning Star and all that it represents. Overall, the virtual exhibition revealed to me as a viewer that the mural holds more significance than what meets the eye. It provided an entrance to experience in my mind the lived-through reality of Morning Star’s becoming, from the first stroke to the final signature, through the thought process of the artist, the reflection of the curator and decisions of the architect. Such as expressed in the video of the unveiling (the process of art showing and art revealing), this mural holds a spirit that is presented to me through this exhibition through my screen. I can briefly imagine the details of the mural’s unveiling which included falling streamers and powwow music playing as the white sheets were pulled, revealing the Morning Star.

“About the Artwork.” Morning Star. Accessed August 18, 2021. https://www.historymuseum.ca/morningstar/explore/?showhs=0.

0 notes

Text

Square Five: The Label

August 16, 2021

In this reading of “The Triumphant Progress of Market Success”, Isabelle Graw examines the relationship between and and the market in which it resides. In her examination, she considers that these two things are not strictly separated as one may assume but that they are two still somewhat autonomous things that share a symbiotic relationship. To further explain, “their relationship can thus be characterized more precisely as a dialectical unity of opposites, an opposition whose poles effectively form a single unit”. Graw then continues to consider the implications of observing art as a commodity, stating that “consequently, the balancing act performed by the artwork as commodity between price and price-lessness is considered as the matrix for the double game played by those who banish the market to an imaginary outside while at the same time constantly feeding it.” As I’ve brought up in previous discussions regarding this idea, yes, this feels comically hypocritical - if art is priceless and therefore there cannot be a ceiling set on its monetary value, then shouldn’t (or can’t) it also be considered that the price of art can approach zero (0)? However, after some further reflection, I’ve realized that while the commodification of art may feel cynical on the surface (i.e. seeing art as money), on the other hand this approach allows us to understand art as something valuable in its production of culture and that culture in itself is something to be valued. Such as how Graw suggests how art depends on the market, if art were to be free-floating without an institution or system, people would not take it seriously as something that creates and moves culture. This can further be passed along the chain of production in determining culture as something valuable not just because we say it is, but because it has a power to influence and progress. Considering this, it was very refreshing how Graw acknowledged in this reading that we should not look at “the market” as an absolute evil “other”. I would instead agree that it may be more productive to understand it as a necessary discomfort, one which both guides yet challenges the art that it both attracts and deters.

On another note, my attention was caught by Graw’s mention of looking at art in relation to luxury goods and making a distinction between the must-haves and must-keeps. A comparison that I would like to mention at this point is to the progression of the scientific world. Even in this kind of realm, the things that are considered as static such as formulas and principles are only theories and concepts in themselves. They may be backed up and strengthened by analytics and quantitative data, but the science world runs on an acknowledgement that things are only “true” (or very, very likely) until they are proven false (if they ever are). I think that this kind of responsible uncertainty is necessary when giving something value because then you are respecting that thing as something that can be tested and confronted. Then, going back to the art world, the difficulty with art and culture is that the “data” is instead qualitative and empirical. However, this data is still data and can be used to strengthen or challenge itself - there is no progress without change. In other words, in the case of art, we should add a “...for now” at the end of the ”must-keep” label because these items (and their values) should not be looked at as absolute.

Isabelle Graw, “The Triumphant Progress of Market Success,” in High Price: Art Between the Market and Celebrity Culture'', Lukas & Sternberg, 2010,19-79.

0 notes

Text

Square Four: The Time-Observer

August 16, 2021

In this excerpt from Giorgio Agamben reflecting on the question of “what is the Contemporary?”, he recalls the ideas of Roland Barthes who summarizes that contemporariness is “... a singular relationship with one’s own time, which adheres to it and, at the same time, keeps a distance from it. More precisely, it is that relationship with time that adheres to it through a disjunction and an anachronism. Those who coincide too well with the epoch, those who are perfectly ties to it in every respect, are not contemporaries, precisely because they do not manage to see it; they are not able to firmly hold their gaze on it.” Those who are contemporary are able to recognize and grasp their own time. They are not static time-” travelers” but rather time-observers. Thus, it may be reasonable to think that they can recognize their own time as a point that exists in relation to other epochs; past epochs which have left their evidence in the contemporary time, and future epochs which will hold evidence from the ‘now’.

I think that the idea of ‘grasping’ (to hold) is quite significant as it is an action that suggests being aware and conscious of the thing you are reaching for; we are only able to “grasp” things we can “see”. Thus, those who are not truly contemporary may brush against the idea of time, but they cannot grasp it. Furthermore, to have a hold on something instills a sense of power - this power is not over time itself but over the allotted time that has been borrowed to us in the time that we live (in our time). Making a connection from this idea to a previous blog post related to Hannah Black’s Review of the 9th Berlin Biennale, it feels as if most people are not contemporary (as in they cannot “see” their own time). Thus, there is no urgency to act in the present. They may react in repulsion of the past or lament over the future, but the over-looming sense of dystopia comes from the inability to distinguish between epochs - as if the past and the future are blurred to the contemporary, and as if the ‘now’ is non-distinct. From the Agamben reading, I am guided to think that we do not and cannot situate ourselves, but we can recognize that we are “situated” - thus we are not just on arbitrarily on a timeline of history, but we are “in-between” two other points of history. So, in reference to the text stating that “an intelligent man can despise his time while knowing that he nevertheless irrevocably belongs to it, that he cannot escape his own time”, I'd like to bring back the idea of the human ego from my other post. Our ego cannot re-situate our contemporary, but it can inspire, alter, or influence the “evidence” left for a future epoch.

Giorgio Agamben, "What is the Contemporary?" In What is an Apparatus? And Other Essays, Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, 2009, 39-54.

0 notes

Text

Square Three: The Ego

August 1, 2021

As Hannah Black reflects on ideas related to race and commodity in her “Review of the 9th Berlin Biennale”, she catches my attention in her statement that “one key symptom of this malaise is that the only thing the capitalist class has to offer workers is a shared dream of whiteness”. From this, and in relation to the overall themes of this review, there is a strange sense or idea that in this world there are white people and non-white people. Reading this, I am reminded of an online video interview conducted on the AsianBoss youtube channel which opened up discussion about what it is like to live as a foreigner in China. One response that stuck out to me was when a white man was asked if there were any challenges in adapting to the new country, to which he replied along the lines of having to drop this preconceived idea of “white excellency”. I mention this as I think it is relevant to how the scope from other places of the world does not see ‘whiteness’ the same way as the Western world. Thus, while there may be paralleling thoughts or strives towards some type of ideal, this shared dream of whiteness does not exist as broadly suggested. As the world becomes more open and transparent in its information-sharing, the pedestal of the ‘white man’ is slowly revealing itself to be rather illusive and self-proclaimed. The exposure of this can be seen in our developing criticisms on concepts such as orientalism and the fetishization or commodification of the “other” race (i.e. all other races that are not white).

Continuing on in the reading of this review, there is a cynical or pessimistic overtone presented by the author, such as in the line “...the apocalyptic emptiness that critics perceive in this biennial is the index of a real emptiness in the world outside it. With Black’s description of some of the artists’ works, it feels as if many of them “reimagine” our world in exaggerations. One particular work she goes into detail about is depicted: the floating installation seems happily unmoored from the anxiety that social life will disappear, instead imagining a post-apocalyptic earth populated by giant rats who are just as full of clumsy mammalian affection as we are. This disaster is full of sweetness: a planet populated by sentient trees, an interspecies hug, a wedding.” Throughout the review, Black also inserts a thought that follows along the lines that perhaps there is an innate human rejection towards technology. Reacting to this, I am reminded of the concept of the Overview Effect, which is a cognitive shift in awareness experienced by some space travelers when they see our Earth as a fragile ball from a distance where borders are invisible and conflicts feel irrelevant. With this concept in mind, I feel that the ‘innate rejection’ can be seen as a testament to the human ego - this ego can also be the thing that pushes us to advance and become something ‘beyond what we actually are (eg. which is being exemplified in the recent social interests in space exploration). And although the dream of space travel becoming casual transit may feel long from now (in relation to the specific lives of currently living people), in the broader timeline of the universe, we are at a point in history when it may be more relevant than ever to make the decision of where we want our egos to take us; to remain static in an unproductive cynical view of our current world, or to extend beyond our current scope of vision.

Hannah Black, “Review of the 9th Berlin Biennale,”Artforum 55, 2016.

0 notes

Text

The Real Image in the “Façades”

July 31, 2021

Link to Exhibition: https://shelliezhang.com/facades

Born in Beijing and based in Tkaronto/Toronto, Canadian artist Shellie Zhang is a multidisciplinary artist whose work explores the contexts and construction of a multicultural society. Through her art, which often visually reflects a collaborative effort of past and present communicative and symbolic iconography, “Zhang is interested in how culture is learned and sustained, and how the objects and iconographies of culture are remembered and preserved“.

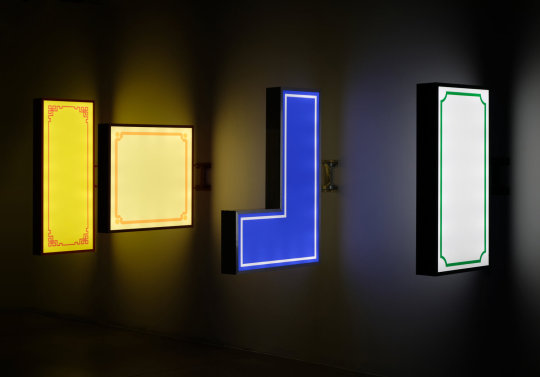

One particular artwork of Zhang’s that follows this same aim in a more specific manner is her 2020-2021 sculpture work titled ‘Façades’. This 18 x 24” work is materialized by electric lightboxes, plexiglass, and powder-coated aluminum, and was presented as a part of her Believe it or Not 信不信 Exhibition displayed with AKA Artist Run Centre throughout Riversdale, Saskatoon.

Visually, Façades appears to be composed of four blank, double-sided, illuminated signboxes which are meant to conjure “images of changing streetscapes” as they are attached perpendicularly to the wall and lined up one after the other - resembling a familiar composition of illuminated light boxes one may see along a real street. The distinct shapes, colour combinations, and (simple) line-patterns which border these four signs leave hints urging towards areas such as Chinatown, or somewhere with heavy East Asian influence/ties/context.

In the words of Zhang,

“Façades captures a combination of nostalgia, regret, and a sudden awareness of time—the feeling of not knowing that something is gone until it has disappeared and failing to remember what used to be there…[with] words and information removed, formal and decorative elements of the signs are left behind, prompting associations and memories of the distantly familiar.”

A part of Zhang’s success in achieving her intended ….can be attributed to Façades simplistic visual depiction of a type of imagery that is perhaps more symbolically significant and iconically recognizable than it is meaningful as a communication channel; the image of the sign itself outshines what is written on it. However, while there is no set of determined text present in the installation, this does not mean that words are completely irrelevant from this artwork as the blank ambiguity of these signs stares at the viewers, welcoming the instinct to associate or familiarize. With this process, the artwork proposes questions to the viewers such as,

“...what constitutes cultural space and heritage, and the subtext of linguistic messages, [...] with the clarity of language removed, what is conveyed to the reader? What is lost through this omission? Similarly, what elements of language and sign propel understandings and sentiments of hospitality or intimidation?”

As perplexing, weighted, burdened, or dynamic as the answers to these thoughts may be, one way to reflect on how we can approach them could be by relating these blank (and iconic) signboxes to the idea of the poor image as introduced by Hito Steyerl in her text, ‘In Defense of the Poor Image’. Briefly explained, a poor image can be described as (but is not limited to) a compressed or reproduced copy... “a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail, an errant idea, an itinerant image distributed for free…”, something that deteriorates as it accelerates.” The poor image is a popular image, it is a result of copy and paste or sharing and it is not constrained to the connection to - or context of - its origin. With this idea of the poor image comes Dziga Vertov’s interpretation of how “the circulation of poor images [...] creates ‘visual bonds,’ [which are] supposed to link the workers of the world with each other.” In reaction to Zhang’s Façades, the ghost of the image [‘traditional’ illuminated signboxes] lives within the viewer’s mind, which can be perceived as a channel of distribution in its own right. As one reacts to the blank signs, contextual value is being added in the process of perceiving the icon of the sign. Perhaps you look at these signs and are reminded of standing amidst a section of the Shanghai Bund surrounded by European-influenced architecture, or you imagine walking through the narrow Hutongs of Beijing, or you remember the streets of a Canadian Chinatown. Furthermore, as Steyerl questions whether there is a “real thing” in relation to the poor image, Zhang’s installation could contribute to a notion that suggests that the “real thing” exists, but it is not singular. Parallel to how everyone will experience a unique reflection on how cultural space and heritage are constituted, the real thing exists as an idea in my mind - and it is different from the real thing in your mind.

“About.” Shellie Zhang. Accessed July 31, 2021. https://shelliezhang.com/about.

“Façades.” Shellie Zhang. Accessed July 31, 2021. https://shelliezhang.com/facades.

“In Defense of the Poor Image.” e. Accessed July 31, 2021. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/.

0 notes

Text

Square Two: The Cube

July 24, 2021

In Brian O’Doherty’s “Notes on the Gallery Space”, he visits the history and conceptual reasoning behind the white cube gallery space. He shares the idea that “...as modernism gets older, context becomes content…”, and he detailed how “... a gallery is constructed along laws as rigorous as those for building a medieval church. The outside world must not come in, so windows are usually sealed off. Walls are painted white. The ceiling becomes the course of light…[the white cube is] Unshadowed, white, clean, artificial-the space is devoted to the' technology of esthetics”.

The white cube allows an evening out of the distance between art and its audience - in some cases, it creates a filtering barrier between the artwork and its current geographical location (to at least some extent), and in other cases, it brings us “closer” to artworks that are contextualized by geographical locations that it is not currently present in. Furthermore, the white cube can be seen as a physical manifestation of a conceptual structure of power, representing something intangible as an inanimate space. Interestingly, this manifestation contemporaneously personifies this inanimate space. Thus, the white cube is not just a tool to display or distance but can be used as a medium that work and artists can interact with and react to.

However, as technology has advanced to become as integrated into our lives as it is today, the possibilities presented by platforms of the digital sphere seem to increasingly challenge the idea of physical gallery spaces. Virtual galleries that imitate the experience or set of ‘real’ physical white cube galleries such as the platform ‘Kunstmatrix’ open direct questions which confront the idea of the white cube. For example, as this reading uses the word ‘artificial’, virtual galleries quite literally add another layer to the non-reality of art-presenting (in fact, its medium is completely ‘artificial’ - human-produced and programmed). In this case, if an exhibition or gallery is meant to be solely/specifically presented digitally, then what is real when nothing is physically tangible? Moreso, there are many ideas and new roles of agency that are being produced from having options to choose from virtual gallery templates (and the ability for an artist to create their own gallery). Two specific templates provided on Kunstmatrix come to mind, one which is a ‘room’ with no doors, and the other is formed by what seems to be an arrangement of walls that are not confined by a room at all - seemingly just floating in space. In reaction to these rooms, I am left to think that in both of these cases, there are architectural/practical structural elements of a “gallery” that have been eliminated. As result, the visitor is either left to be free in some type of a free-floating interweb space, or they are trapped within the void of a gallery with no way out. Except there is a way out; to close the tab on their screen. It could also be thought that the viewer was never really in the exhibition space, to begin with. With all of that being considered, this digital kind of gallery space is still rather successful in ‘isolating’ the artwork (just like the white cube), and it is a new kind of medium that we’ve never encountered until recently. In a way, it directly confronts the traditional white cube’s physicality in the sense that it reminds the ‘white cube’ of its truly conceptual existence; it reverts the inanimate space to the idea.

Brian O'Doherty, “Notes on the Gallery Space,” in Inside the White Cube: the Ideology of the Gallery Space. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

0 notes

Text

Look at What You Don’t See

July 21, 2021

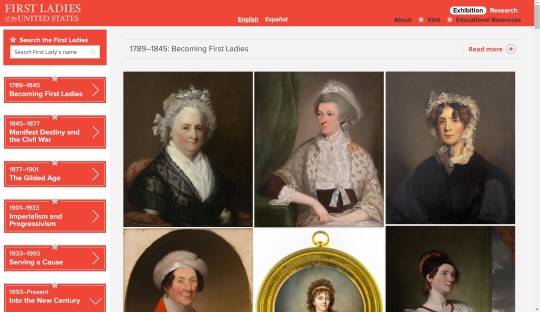

Link to Exhibition: https://firstladies.si.edu/gallery

“Every Eye Is Upon Me: First Ladies of the United States” is presented as an online exhibition by The Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery (Washington, D.C.). This exhibition is published in the form of a website that comprises a historical timeline of the women who have held the position of FLOTUS (First Lady of the United States), shedding light on a historical focus that has rarely been perceived as anything more than peripheral. This collection of images which have been acquired by donation and commissions aim to “[recognize] the innumerable contributions made by women to our history and culture [through] the portraits of the nation’s first ladies. As our eyes are placed upon these portraits, one is led to contemplate the impact and marks left by these women who are presented to us.

My first honest impression when experiencing this exhibition was that it reminded me of a website I would stumble across while doing research for a (pre-university) school project. It actually triggered a very specific memory of working on a 3rd-grade history project about world leaders. By making this connection, I was left with a need to reflect on what the virtual medium of presentation of this exhibition implied outside of itself. As the interface of this exhibition was very “kid”-friendly or “educational”-looking, I began to feel rather optimistic about the changing ways in which information is being delivered and taught. I also find this exhibition to be very in tune with our current climate of historical examination; as we are reconsidering not only the events of our history but also how that history was documented and from which perspectives were they derived. As this kind of conversation is concurrently being had alongside those of censorship (which feels almost opposite in a way), it is interesting to see how the sharing of information will develop within the push and pulls of information-hiding and information-revealing. This has made me reconsider what I had always heard and referred to as the information overload that exists on the internet. Perhaps we should not look at it as an excess of information but simply making up for the lack of information that was previously invisible. Such as in the case of this portrait collection, the histories and influence of these women are not fiction created for the sake of the exhibition.

Furthermore, the text used in the descriptions and title of this exhibition is significant in how they bring to light themes of power dynamics that exist both in relation of the portraits to the viewer, but also between the actual women depicted by these portraits and those who regard them in the real world. For one, the language found in this exhibition does not reduce the woman to “a wife of” a man, but she is simply married to a man. Furthermore, the title “Every Eye is Upon Me…” subtly alludes to the historical objectification of women, as well as directly confronts the fact that these portraits are indeed to be stared at. And as we look through these portraits and read their correlating texts with the lens that their context is the main context, a new understanding of the role of FLOTUS develops, symbolically as both a reflection and a direction. When every eye is upon you, you are in power yet you are also left completely vulnerable. As I scroll through, I am met with recollections of the past such as how Melania Trump’s nationality stirred just as much questioning as Barack Obama, how Michelle Obama was criticized for looking strong, and how Hilary Clinton is constantly compared as a foil to her male counterparts by the media. I realized that in fact, our eyes have always been upon these women.

“Every Eye Is Upon Me: First Ladies of the United States” - The Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery (Washington, D.C.)

0 notes

Text

Square One: The Net

July 16, 2021

In their publication of “Tell Us What You Really Think: A Survey on the Landscape of Canadian Art Criticism,” Esmé Hogeveen and Emma Sharpe share a collection of voluntary responses to curated questions related to the current state of art criticism in Canada. Presented in a friendly and familiar format as one may have seen before in the likes of Seventeen magazine quizzes, the responses reflect the anonymous thinking of C Magazine contributors, their colleagues, and friends. Curious about the attitudes towards Canadian criticism, this interview starts off with a broader inquiry of “what do you see happening in Canadian criticism that excites or inspires you?”, and ends on a more specific contemplation that asks one to “paint a picture of your ideal Canadian criticism landscape; what’s the utopia we should aim for?” In reflection of this reading, I’d like to focus on the recurring attitude that can be sensed in many of the answers throughout which suggest a lack of inspiration and urgency; it feels as if our current landscape lays on a plateau and our criticisms dangle its feet in a false sense of danger as we are constantly checking that there is still a safety net underneath. In other words, as uniquely and accurately described by the interviewers, the “...Canadian art world’s claustrophobia can sometimes restrict frank public conversations”.

One reason for this could be linked to another theme discussed in the reading regarding Canada’s multiculturalism. In terms of cultural progression (specifically in relation to art and art criticism in this case), we may have found a point where one of Canada’s most celebrated strengths may actually be a source of weakness - or rather, it may more productively be perceived as a hurdle that we are still working to overcome. Rather than leaping over this hurdle in an abrupt sprint, is one that we must cautiously step across. From the attitudes gathered from the interview, it feels as if we have instead walked around this hurdle, cautious to avoid any consequences of it potentially falling over; our criticism feels wishy-washy and non-confrontational. And when we are confrontational, it is the same thematic critiques and issues that are being brought up time and time again with similar but slightly different perspectives. Comparing our current criticism landscape to that of other countries, there are some that may feel rather reckless (such as our Southern neighbours) in leaping over these hurdles, but with this “recklessness” comes the sense of urgency that the Canadian scene is currently lack-luster of. Simply put, our criticism can come off as feeling “safe” in comparison. It seems that rather than voicing strict opinions, our landscape is more concerned with how the same opinions are being voiced. In a more positive way of looking at this, we can view our approach as simply a different way to progress forward. We are not as “reckless”, but we are thorough - we will be prepared once the tipping point off of the plateau arrives. But in this case, the question that is left is when will that point come...if it does?

While there is no clear answer to this, perhaps a potential tipping point will come through a form related to memes/internet culture. One cause for our standstill may be because our ‘criticism’ landscape is not really much of a conversation but rather it is a lecture - the kind that is so accessible that people choose to not access them at all. On the other hand, platforms that dominate in internet culture, such as Twitter and Instagram, allow and thrive on the basis of conversation and back-and-forth call-to-actions. If looking at the art sphere as a literal enclosed ball, I’m inclined to think that the current socio-political climate has poked a tiny hole in this sphere - one that is slowly letting in the “outside world”, eventually becoming a hole that we can no longer patch. This eventual burst, that is the tipping point.

Esmé Hogeveen and Emma Sharpe, “Tell Us What You Really Think: A Survey on the Landscape of Canadian Art Criticism,” C Magazine 145, Spring 2020.

1 note

·

View note