Text

The qualities that divide good children’s literature from bad children’s literature:

1) The dragons are real.

2) The adults don’t believe you.

will elaborate

62K notes

·

View notes

Text

me then (young, naive): i dont swear because there are better choices to make with my vocabulary

me now (older, wiser): I am master of all the words, and fuck is the best one

73K notes

·

View notes

Text

gonna post a controversial take alright are y’all ready??

…

actually typing out emoticons like XD and :D and :V never should have gone out of fashion and you can pry them out of my cold dead hands okay I know emojis are fun but THEY DON’T CAPTURE THE EMOTION IN THE SAME WAY

so like

…yeah that was basically it, thanks for reading

170K notes

·

View notes

Text

Grammar Shaming Is Not Only Rude, It’s Just Straight-Up Outdated

By: Dara Katz

| Mar. 5, 2021

There’s a reason that those who know a bit about grammar become its enforcers: Nobody else really seems to care about it. Like a lonesome fine arts restorer in the basement of The Met, grammarheads typically work independently, but with the steel-driven purpose to remove debris that’s collected on the face of language. Is there any first responder quicker on their feet than a grammar fanatic? (“Jambalaya and I <3,” reads the first comment on your post about putting your beloved dog down. Thanks, Aunt Hilda.) They are the watchmen of language, the last guard of dangling modifiers, Strunk and White and Oxford commas…and before you open a new email to blast me, we do not use serial commas at PureWow.

As an English major and now professional writer and editor, I too have felt that electric tinge when spotting and correcting a grammatical error. Is there anything more cathartic than slashing a red pen through a completely misguided capitalized letter like Zoro through a white sheet on a clothing line? But as much as I can appreciate the adrenaline rush of diagramming a sentence, I also, admittedly, have my own shortcomings: My idiom recall is wonky—for instance, the post office is the mail station—I’m a slow reader and a mediocre speller at best. Every syntactical and semantical choice I send out into the universe feels ripe with trip wires. One wrong step and the grammarheads have me in their crosshairs ready to shame me.

And while there’s nothing new about grammar shaming—the act of pointing out an “incorrect” usage of language—there is something stale about it. Yes, grammar is important. Its purpose is to help us communicate more clearly. A single comma can change everything: “Call me Daddy!” vs. “Call me, Daddy!” is the difference between a line of dialogue in a porno and a line of dialogue in a Taken film.

Copy editors, style guides, etc.—these are important for consistency of the written word in certain circumstances. Publications should employ a set of rules for the words that live on their pages. Teachers teaching grammar should be able to require students to execute it correctly. Screenplays should be punctuated clearly so we know if the scene should be delivered in more of a sexy-pizzaman tone or a Liam-Neeson’s-daughter-being-kidnapped tone.

But grammar is not physics. It does not exist without us in the natural world. It is something we, collectively—from the macro societal scale to the linguistic politics of our nuclear families—make up as we go along. As fast as the folks at AP, MLA and Chicago work to enforce their style guides, the nature of how language evolves means that those creating the rules around language will always be ten steps behind.

And let’s be honest, most of the time, despite grammatical missteps, we can understand what a person is trying to communicate. Watching a recent episode of The Real Housewives of Dallas, Tiffany, a highly educated anesthesiologist, laughs and corrects Kameron, an archetypal blonde bimbo (a costume that she strategically chooses to step in and of at her own liking), for a series of grammatical errors—conflating the adjectives “two-faced” and “contradictory” and also not knowing the meaning of “cathartic.” Kameron responds by asking Tiffany if she likes making people feel stupid, and while we can get into the Tiffany v. Kameron feud another time (#teamTiffany: I believe Kameron’s chicken feet comments are actually far more harmful), Kameron raises a fair point. (Here’s an actual clip of the conversation.)

Tiffany thinks she’s helping Kameron by teaching her to speak correctly, but Kameron feels belittled. Even without Tiffany’s correction, everyone got what Kameron was saying. So what’s the point of calling her out? Is it just to humiliate her? And, not to get philosophical, but if we know what Kameron’s saying, even if she is saying it “incorrectly,” then she’s still saying it. Sure, Kameron Westcott is rich as hell and probably had one fine education, but who are we to monitor how her brain works? Or how anyone’s brain works?

Which brings me to one of the most important reasons we should stop the shaming: dyslexia. Dyslexia is a learning disability characterized by difficulty reading. And while dyslexia takes many shapes and forms, it often extends to grammar learning. According to The Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity, “Dyslexia affects 20 percent of the population and represents 80 to 90 percent of all those with learning disabilities.” Twenty percent of the population? That means that every one out of five times you correct a person’s misuse of something as stupidly complicated as a homophone (words that sound exactly like each other but are spelled differently), you are potentially telling this to someone who’s already been told something like this every damn day of their life. There are brilliant minds who can’t for the life of them figure out which witch or which their, they’re or there to use. It is not a reflection of someone’s intelligence. It is not a blatant disregard for the rules. It’s literally the way 20 percent of the population’s brains work.

But it doesn’t end there. What seems like a minor correction or “trying to help” can actually just make someone who’s already vulnerable within society feel even more exposed—essentially punishing someone for a disability, for their socio-economic upbringing or culture. The more we understand about dyslexia, the less we should care about whether someone used the wrong “their.” The more we understand that the system is broken, that while one class of sixth graders is learning about the past participle while another is reading at a third-grade level, the less we should care if a candidate’s resume has a spelling error. The more we understand about the power of language and identity, the less we should care about trying to make those we deem “other” sound more like us.

At its best, grammar policing enforces rules that help us communicate more clearly. At its worst, it’s a set of arbitrary rules that allows some people to climb the ladder while holding others back. And isn’t the whole point of language to set us free?

Either way, if we needed Liam Neeson to come rescue us, we have a feeling he’d get the gist, with or without the comma.

1 note

·

View note

Text

you literally have to laugh or else you’ll cry when you see parts of a syllabus that are like “i know we’re living in really hard times! :( it’s important to take care of yourself! :( this environment is SO tough right now! :(” and then like immediately after it it says “late work will not be permitted you are expected to be in class every session”

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

posting on a blackboard discussion board and replying to two of your fellow students has to be one of the nine circles of hell

141K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Enchanting Bookworm Inspired Digital Illustrations by Simini Blocker

NYC based illustrator Simini Blocker understands the enchanting world bookworms revel in. From Hogwarts to Neverland or King’s Landing, Blocker captures the spellbinding imaginative realms literature has introduced to us with vibrant colours, gorgeous brushstrokes and fitting quotes from our favourite authors. You can find her gorgeous illustrations on Society6 and Etsy.

View similar posts here!

Keep reading

107K notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding Logical Fallacies

If you’re just learning how to write essays or you want to improve your arguments in an essay, it’s important to look at logical fallacies. These explanations should help you avoid creating fallacies and help you find them when deconstructing others’ arguments. I will be using South Park to help explain the most commonly used logical fallacies.

Mr. Mackey is the perfect example of a circular argument. He uses the same argument in his premise to support his conclusion. For example, Mr. Mackey often says, “Drugs are bad M’kay. So don’t do drugs because they’re bad.” Mr. Mackey has shown no evidence for what makes drugs bad, he has just repeated his opinion.

Another fallacy is Post Hoc: one event is said to have caused a later event simply because it happened earlier. So, when Randy says the town getting a Whole Foods caused kids to come out as gay, he’s assuming no kids in South Park were gay before. The issue is he has no evidence the first event effected the second event.

Generalization is the fallacy of making a universal statement about a group of people with insufficient evidence. When Randy says Stan is “funny” or implying he’s gay, for only hanging out with Kyle, he’s making a sweeping statement about homosexuality. Randy is assuming that any boy spending most of his time with another boy must be gay. He’s generalizing homosexuality behaviour based on their society’s opinion instead of evidence.

A Red herring is an observation that draws attention away from the central issue in an argument or discussion. For example, Sharon talks to Stan about the merits of an individual vote when he’s actually concerned about disliking both candidates. The episode’s central issue was about being stuck with two undesirable choices, but everyone focuses on the privilege to vote. Red Herrings bring up unrelated topics and problems that don’t connect to the main discussion. In other episodes, Cartman often creates Red Herrings that distract from the central issue, by arguing about the “flaws” in Jewish people.

Bandwagon is an argument based on the assumption that the opinion of the majority is always right. This fallacy also makes the assumption that the majority is what’s normal and makes sense. For example, the Goth kids don’t want to “jump on the bandwagon” and wear clothes from the Gap like every other kid. The Bandwagon mentality is often about giving into status quo and not forming an opinion for yourself. Another bandwagon example is the episode all the guys in town dress metro-sexually, except for Kyle. The other boys tell Kyle he should dress metro-sexually because they decided to.

Slippery slope is assuming a course of action will lead to many consequences till an undesirable result happens. However, we can never know if a certain result is determined to follow one particular event. Cartman also displays this fallacy, as he often reacts delusional to topics he has little information on. For example, in the ginger kids episode, Cartman argues, “The ginger gene is a curse and unless we all work to rid the Earth of that curse, the gingers could envelope our lives in blackness for all time.” Cartman has no evidence of red haired people being inherently evil or dangerous. Instead, he let’s an irrational fear of ginger kids make him believe unlikely scenarios will occur.

Ad hominem is a personal attack based on the adversary’s flaws instead of the merits of the argument. When Mr. Garrison says he doesn’t trust women because they menstruate, he is attacking a biological aspect women can’t control, instead of pointing out an untrustworthy action or statement by the opponent.

Straw Man, is when the opponent’s argument is overstated or misrepresented to be easily refuted. For example, the journalist misrepresents Wendy’s argument against photo shopping pictures of women. He claims she is actually jealous and a “hater” to make her argument appear weak.

The either or/false dilemma is an argument where only two options are available, when there’s actually numerous alternatives.For example, Jimmy saying to Nathan he can only be a nice kid with no gun, or a bad kid with a gun. South Park episodes often use binary conflicts to show how ridiculous it is to think a situation only ever has two sides. When characters pressure the boys into thinking there is only two solutions to a problem, they often find there are many answers to the issue.

Finally, a non sequitur is an argument where the conclusion doesn’t follow logically from what preceded it. PC Principal often uses the fallacy to support his beliefs. For example, he argues that gay kids need support. However, giving money to kids for being gay is random and does not show tolerance towards them. There is no relevant connection between his claim and support for it. Hopefully these explanations help with your essay writing and general analyzing skills. Please go check out the blogs I used gifs from. :)

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

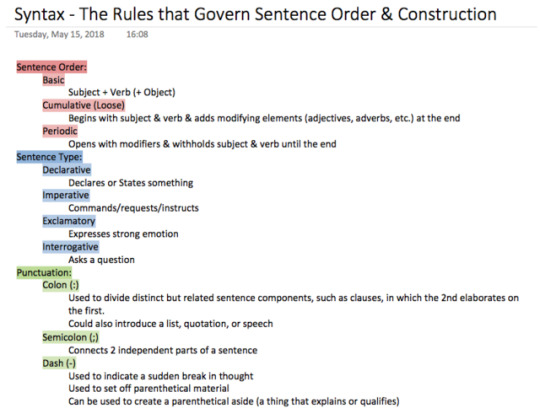

The Rhetorical Handbook

Syntax, Rhetorical Devices, Rhetorical Appeals, Logical Reasoning, & Fallacies are all defined here!

291 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everyone’s like “those Germans have a word for everything” but English has a word for tricking someone into watching the music video for Rick Astley’s Never Gonna Give You Up.

467K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ingredients of Persuasion

Otherwise known as the lauded “big three” of rhetoric in the English language!

Rhetorical Devices are the devices used in the art or study of using language deliberately, (not accidental – intentional!) effectively, and persuasively. Almost all rhetorical devices that are used fall under the categories of ethos, logos, or pathos – otherwise known as Aristotle’s Ingredients of Persuasion. Being able to identify these three devices will make analyzing, annotating, and writing a million bajillion times easier (especially in argumentative settings)!

Ethos: Greek for character. Refers to the trustworthiness or credibility of the writer or speaker. Ethos is often conveyed through tone and style of the message and through the way the writer or speaker refers to differing views. It can also be affected by the writer‟s reputation as it exists independently from the message – his or her expertise in the field, previous record or integrity, etc. The impact of ethos is often called the arguments ethical appeal or the appeal from credibility.

The author is a trained expert in the topic or holds an important position in the topical field.

“My three decades of experience in public service, my tireless commitment to the people of this community, and my willingness to reach across the aisle and cooperate with the opposition, make me the ideal candidate for your mayor.”

Logos: Greek for embodied thought. Refers to the internal consistency of the message – the clarity of the claim, the logic of its reasons and the effectiveness of its supporting evidence. The impact of logos on the audience is sometimes called the argument’s logical appeal.

The author cites a collection of statistics supporting their claim.

"Ladies and gentlemen of the jury: we have not only the fingerprints, the lack of an alibi, a clear motive, and an expressed desire to commit the robbery… We also have video of the suspect breaking in. The case could not be more open and shut.”

Pathos: Greek for suffering or experience. Often is associated with emotional appeal, as it appeals to the audience’s sympathies and imagination. An appeal to pathos causes an audience not just to respond emotionally but to identify with the writer or speaker’s point of view – to feel what the speaker feels. In this sense, pathos evokes a meaning implicit in the verb to suffer – to feel pain imaginably.

The most common way of conveying a pathetic appeal is through the narrative or story, which can turn the abstractions of logic into something palpable and present. Pathos thus refers to both the emotional and the imaginative impact of the message on an audience, the power with which the speaker‟s message moves the audience to decision or action.

The speaker uses diction that has emotional connotations or recalls a personal anecdote to pull the audience’s heartstrings.

"If we don’t move soon, we’re all going to die! Can’t you see how dangerous it would be to stay?”

So those are the basics of the “big three” of rhetoric, formally known as Aristotle’s Ingredients of Persuasion! Here’s a little printable of these notes too!

267 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I ask students if they finished their assignment

1K notes

·

View notes