curusblog

4 posts

Curus Art Consultancy - Evidence based art for healthcare and wellbeing - Writing by Jennyfer Ideh

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Curus founder Jennyfer Ideh regularly contributes to Elite Living Africa magazine. Please scroll to see some articles.

0 notes

Text

Of Earth, Wind and Fire

Epic land art and the burgeoning West African art market are the two focuses of Elite Living Africa’s art expert for this issue.

Art enthusiasts will agree that the power of a work can rarely be confined to the canvas edge. Whether we mean stretched and pre-primed linen, or a more metaphorical use of the term, the artist’s message can reach far beyond its physical representation.

In the case of Andrew Rogers, that metaphorical canvas is the very face of the Earth, and the message is best viewed from above.

The artist has spent just shy of two decades executing the largest land art project in modern art history. Entitled Rhythms of Life the project comprises 51 large scale stone structures, which are spread across 16 countries and seven continents to form a network of stone ‘drawings’ that are visible from space. These giant stone structures are built to endure; Rogers states that “without memory we are nothing,” reflecting his belief that we come from a common history of people, whose traditions we are compelled to honour and preserve. Although varying belief systems have evolved over millennia, at their base, all religions and philosophies touch on the eternal. Accordingly, each project features symbols of local significance, and is finished with a common Rhythm of Life sculpture; a symbol created by the artist, this Rhythm of Life references the individual’s trajectory within our common experiences of time and space.

The chosen sites for each of the projects are liked to the prehistoric traffic routes of our ancient inhabitants, while the stone structures, measuring up to 20 metres in height, reference the fundamental materials of the Earth. We are humbled when viewing the works from above, whether by helicopter or high resolution satellite imagery — those great 20 metre structures very quickly diminish in size as the artist reminds us that we are a part of nature and not its master.

After crossing the Earth to seek out its most remote corners and braving challenging environmental conditions, the Rhythm of Life structures can now be found in deserts, fjords, altiplano and mountain valleys, at altitudes ranging from below sea level to 4,300 metres above it.

Two of these sites are to be found in Africa.

In August 2012, Rogers completed Sacred Fire, a stone structure in the Namib Desert, in far north-west Namibia. One of the most remote locations in southern Africa, the Namib is characterised by its harsh dry climate, rugged mountains and sand dunes. Humanitarian activities play an essential role in each project and Rogers takes care to involve as many local people as possible, paying equal wages for the contributions of men and women. For Sacred Fire he was assisted by 85 participants from the Himba people, considered to be the last true nomads in the world. The Himba connect with their ancestors through a sacred fire — a centuries-old tradition that sees a flame kept alight continually. After consultation with the elders of the tribe, it was agreed that the traditional surround of the sacred fire would be constructed. That structure measures 14 metres in diameter and stands in homage to the community.

In the same year, Rogers completed another project in the Chyulu Hills in Kenya. This time, local participation saw the single largest gathering of Maasai tribespeople in recorded history — a total of 1,270 men and women contributed to the project. Again, tribal elders were consulted and it was decided that three forms would be constructed including a lion’s paw and a shield, key symbols in the life of the Maasai representing the bravery of their warriors. When asked for one of his greatest memories from his years creating The Rhythms of Life, Rogers spoke warmly of the shield that the Maasai assembled to present him with as a parting gift.

The Rhythm of Life series inspires us to embark on a pilgrimage of sorts, encouraging reflection upon the overlapping nature of human history as we visit each of the diverse sites. Should we like a more readily accessible viewing of Rogers’ work, we can make a (perhaps second) trip to visit the Venice Biennale. We Are is a series of eight bronze and stainless steel sculptures and a continuation on the theme of humanity’s interconnectedness. The works are on display at the Palazzo Mora until the close of the Biennale on the 26th November.

Is now the time to collect West African artists?

The Africa Now modern and contemporary art sale earlier this month at Bonhams suggests so.

An inspiring catalogue was exhibited at the New Bond Street branch in London, and a packed saleroom on the 5th October saw an estimated £1.47 million of lots sold.

Three pieces by Ben Enwonwu were the top selling works: Nigerian Symphony, a large scale work painted at a pivotal moment of Nigerian Independence sold for £112,500; Female Dancer and Negritude on Red also performed well, closing at £112,500 and £106,250 respectively against estimates of £60,000-90,000. Giles Peppiatt, the Director of African Art at Bonhams retained that he was “not surprised” that bidding was fierce for the father of Nigerian Modernism.

There were new world record prices at auction for Nigerian artists Demas Nwoko (Metro Ride, a rare painting from 1962 considered the most significant of the artist’s career, made £81,250) and Erhabor Emokpae (Struggle between Life and Death was hammered down at £31,250).

Interesting post-sale scouting opportunities are the gestural works of Ghanaian-born Ablade Glover, and the carved wood sculptures by fellow countryman, the internationally-acclaimed El Anatsui.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Noble Causes

An unassuming member of an Indian royal family is focusing on art and humanitarian causes across the world.

Tucked away on an unassuming street off London’s Chapel Market sits one of the city’s most exciting new galleries. Amir Gallery is a recent project by Amar Singh, the humanitarian and cultural activist of royal Indian lineage.

“Does the prince prefer to be addressed formally?” I asked the royal representative before our first meeting. “Dear Jennyfer, please call him Amar.” The cordial reply was a fitting preamble.

Despite being a member of the Kapurthala Royal Family, as well as an impressive list of accomplishments in his twenty-something years (…a Harvard degree, a position as advisor to the Andrea Bocelli foundation, supporting several international humanitarian projects, a solid presence on the international art scene…), Amar Singh remains thoroughly down to earth. He dedicates his time to diversity in the arts, and to championing the most vulnerable voices worldwide. We spoke with the gallerist ahead of London’s Frieze week this coming October, during which the gallery will show work by Lina Iris Viktor.

ELA: There are one or two versions of the Kapurthala Family story. How would you describe your family? AS: The Kapurthala Royal Family is one of the oldest royal families of India. Whilst I am proud of my family and heritage, I grew up in London and do not consider myself royal. In 1971 the chamber of princes within the Indian government was abolished — many people still refer to members of Indian royal families by their titles, however this is an environment which I was not surrounded by.

ELA: In that vein, how would you describe yourself? AS: A fighter for equal rights and a lover of art.

ELA: You are somewhat of a cultural and humanitarian ambassador for your family - can you tell us about some of your activities? AS: I hope I can make my family proud with everything I do. I have been focused on LGBT rights and women’s rights in India for over ten years. India is an amazing country, the first country in the last century to elect a non-Indian female as the leader of a main political party (Sonia Gandhi). This highlights how progressive our country can be on one side but there are still many problems due to a lack of education and population number: there are forced marriages, honour killings, rapes, child prostitution, and slavery that prevail. I have been working to rid the country of these problems alongside many people. When we unite as a nation and champion women then India will truly prosper.

ELA: Regarding cultural activism, could you tell us something of the Kapurthala Royal family collection? Where did the desire to collect come from, and who has been most actively involved? AS: Various members of my family have been collecting throughout the years. A large part of the collection is Renaissance art. One of my ancestors, Maharajah Jagatjit Singh, would often buy art during his trips to Europe. A number of works by Indian artists from Raja Ravi Varma to S.H. Raza are also in the collection. I have been chiefly responsible for the contemporary works in the collection by artists such as Julie Mehretu, Jacob Lawrence, and Glenn Ligon.

ELA: Do you have any personal favourites in your collection? Which works do you most enjoy looking at right now? AS: I love all the art that I’ve been able to acquire. The works which I’ve been looking at the most are the recent acquisitions of works by Melike Kara, Guy Yanai, and Mary Weatherford.

ELA: In regard to the Amar Gallery, can you share the ethos behind your new space in London? AS: We are an interdisciplinary gallery showing artists from around the world and supporting the artists’ goals. I did not want to pigeon-hole myself by just representing Indian artists for example. There will always be a new generation of artists that will be part of art history. This generation, especially now, will be a diversified group from a wide range of backgrounds and I aim to support as many of them as I can.

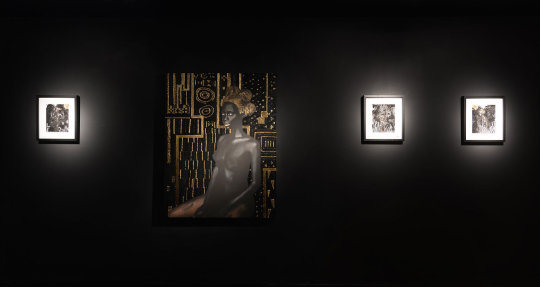

ELA: You’re showing Lina Iris Viktor at your gallery during Frieze. It is such strong work - what can we expect from the exhibition? AS: The exhibition is entitled Black Exodus: Act I - Materia Prima. Presenting large and small scale gilded works on canvas and paper (gilded with 24-carat gold — ed. note), the exhibition highlights the co-dependent relationship of light and dark, within a folkloric universe of the artist’s creation. Taking a new Exodus tale as a point of departure - a mythologised dystopia where the black race itself has been extinguished - Viktor’s works interrogate the implications of this theoretical future.

ELA: When not in your gallery, where can we find you during Frieze Week? AS: At the theatre or somebody else’s gallery.

ELA: The art world can be a glamorous circus at times — how do you like to disconnect in your downtime? AS: I prefer to focus on my human rights work.

ELA: If you weren’t doing what you’re currently doing…? AS: Running for public office to represent and help the people who need it the most.

Black Exodus: Act I - Materia Prima will be on show at Amar Gallery from 12th September. The gallery is at 48 Penton Street, London N1 9QA.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stepping Up To The Plate

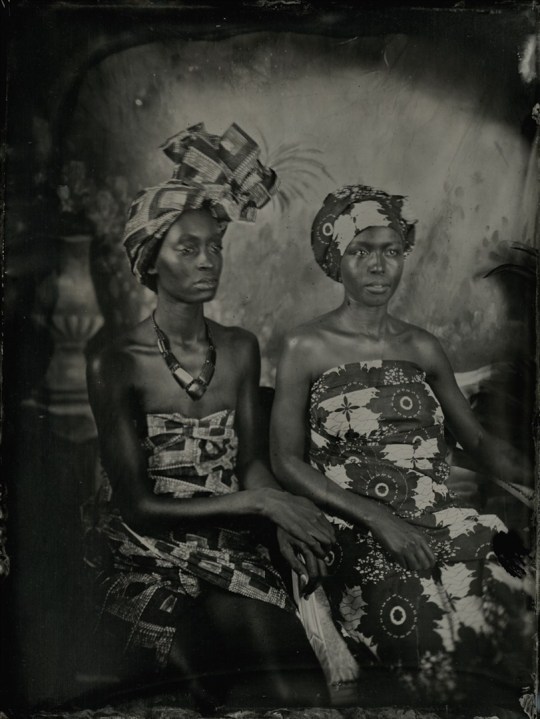

A French photographer pays homage to Africa at an exhibition in London using the time-honoured wet plate technique.

Nicolas Laborie wants to take us on a journey. If we will follow his lead, we are afforded a glimpse into the artist’s world of unconventional portraiture. We meet immaculate sapeurs from Brazzaville; Japanese lolitas performing innocence in school uniform; Wild Ones wearing tattoos like armour; British chavs in Burberry stripes as loud as their voices. Crucially, though, Laborie wants us to journey with him through time.

The French-born, London-based photographer has just unveiled his latest body of work. Entitled Tin Tribes in the Garden of Ether, Laborie returns to the origins of photography; he works with wet-plate collodion — a 19th century technique developed by Englishman Frederick Scott Archer, it is one of the first photographic processes ever invented. With Tin Tribes, Laborie presents a series of prints and original artworks, as well as a linen-bound photographic book.

As he brings images to life in his darkroom, Laborie is part creative, part chemist. Smartly dressed yet armed with an apron and face-mask, he first prepares a highly volatile and highly flammable liquid — a mixture of ether and silver nitrate crystals which the artist combines in the just quantities. This emulsion-like liquid is then transferred to a plate, ready for exposure of an image captured by the artist’s eye. In the earliest versions of wet plate photography, the colloid is spread across a clear glass plate, producing a negative image once exposed. With tintype photography, Laborie uses opaque plates so that each image produced is a direct positive. Once developed, the image can be appreciated immediately — and indeed each metal plate is an original artwork in its own right. The wet plate process is lengthy, sophisticated, very expensive and highly dangerous — the final image is testament not only of the photographer’s eye, but also of his dexterity with chemical substances. It is also historically significant. In Laborie’s case, the result is a happy anachronism: vintage process, contemporary subject matter.

At the heart of Tin Tribes we find a number of international cultures - those stylish Congolese sapeurs, Japanese lolitas and wild rockers. By capturing groups of individuals who have chosen to self-define through their alternative lifestyles, Laborie’s work explores greater themes of identity. A poignant social commentary runs through the series, connecting disparate, international tribes with universal concerns. Tin Tribes seems to ask us: who is worthy of having their picture taken? Who should have their image immortalised for future generations to contemplate?

‘During the Victorian times, it was mainly wealthy, powerful people who were in the position to have their portraits taken…”

Laborie is making his way through the Royal Academy when we speak via telephone. He has just finished varnishing his work, African Queens, an original tintype from the series, which will be exhibited as part of the RA’s Summer Exhibition. We speak at length. He is enthusiastic when talking about the sapeurs, and how their uniforms of three-piece tailoring and bespoke leather shoes were borne out of political resistance. We also speak about his African Queens, whose traditional dress and jewellery is contrasted against the hand-painted backdrop of a 19th century English garden. With their regal postures, however, his queens do not look one bit out of place.

In an age of digital photography and photo retouching, Laborie’s work is exciting. We are taken back to a time when having one’s portrait taken was an event — and with the dangers and margin for error that come with wet plate photography — each successful portrait is indeed an event to be celebrated.

Tin Tribes in the Garden of Ether is available as a photographic book in a limited edition of 70 copies, while the African Queens original tintype is on view at the Royal Academy from 13 June to 20 August 2017.

0 notes