I'm Dan Golding, writer and academic. Here's my twitter, my journalistic writing, and my academic stuff. This tumblr is for things that don't go anywhere else.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Spec Ops: The Line and the fine art of subversion

Every writer has a piece that they never quite got placed with a publication. I wrote this many years ago now when Spec Ops: The Line was first released and showed it to a few friends and editors, but it was never published. Now that the game is five years old, I thought I’d just put it online.

///////////////////////////////

And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there

The first thing you encounter in any videogame is its menu. People generally spend very little time on menus—they are doorways, the thresholds of videogames, ready to set the tone but quick to get out of the way. Despite their importance, they are often relatively disposable for the player, and quickly forgotten. Press Start. Hit A to begin. Now here’s the real game.

But the first thing you notice about Spec Ops: The Line is its menu. It is not here to get out of the way, to be an open door between the player and the ‘real’ game. It is here to make a statement. A dilapidated American flag takes up much of the screen, flying upside-down, either a sign of distress or a deliberate desecration. In the distance sits a Dubai in sandy ruins, the contemporary symbol of capitalist expansion and reach destroyed.

Playing over the top is Jimi Hendrix’s famous 1969 Woodstock performance of “The Star Spangled Banner”. The sonorous, roundly distorted notes signal its arrival half a phrase in; the manic, free-form drumming of Mitch Mitchell barely audible in the background. Already, The Line is in many ways radically different for a standard military-themed videogame. In the place of the usual proud flags and dutiful trumpet calls, The Line populates its menu with complicated and troubling symbols.

Of course, The Line is a deliberate attempt at subversion. Military shooters have long been at the core of the videogames industry (the latest installment in the Call of Duty franchise, for instance, grossed over $400 million in its first 24 hours on sale late last year), and while sometimes technically innovative and exciting, few of these games have very much to say. Some, like the Modern Warfare franchise, will occasionally look to have the appearance of philosophizing on war, but generally, the most generous conclusion to take from these sorts of games is something like this: War is hell. War is also spectacular. The people who choose to go into it and come out alive are amazing.

It’s in this context that The Line presents itself as a sweeping counter to the traditional claims of the military videogame. It isn’t all just upside-down flags and Jimi Hendrix, either. The game’s plot is for the most part, a fairly reasonable appropriation of the general thrust of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. We follow three soldiers—Sergeant Lugo, Lieutenant Adams, and Captain Martin Walker, the last of whom the player controls—as they journey into a Dubai of the near-future, one that has been destroyed by dust storms. A battalion lead by a Colonel John Konrad (in the game’s most guileless reference to Heart of Darkness) has disappeared in the city, and as we find out, has of course gone rogue.

Throughout your journey to look for survivors, Spec Ops continually throws horrifying experiences directly in the face of the player. Needless, limitless bloodshed, civilian massacres, warcrimes.

But The Line’s most unexpected move is its bold indictment of the player in this context. You did this, the game says. Not us, the designers, not the characters, but you. It’s all your fault.

*

When Jimi Hendrix performed “The Star Spangled Banner” at Woodstock in 1969, many, if not most onlookers assumed it was an antiwar statement of sorts. Hendrix’s unorthodox performance was not the first controversial appropriation of America’s national anthem (Jose Feliciano had played a folk-ish version a year earlier at a Baseball match, the fallout of which he claimed stalled his career for a number of years), but it was certainly its most violent. Strewn between the heavily distorted, oppressively bland notes of the anthem were Hendrix’s own embellishments. He threw his plectrum up and down the strings, smashed away at the pitch-bending tremolo arm, and deliberately induced piercing feedback.

The fact that most of these embellishments coincided with the lyric, “and the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air,” just reinforced the idea that the performance was about the Vietnam War. The rockets’ red glare was being broadcast on television screens every evening in 1969. It was hard not to take it literally. Hendrix’s slides became missiles, his muted strumming became gunfire (much like his later song, “Machine Gun”), his distortion became bombs, destruction, and cries of the innocent. Played into Jimi Hendrix’s guitar were the nightmares of a generation of disillusioned Americans, his instrument an orchestra of national disaster.

Hendrix’s Woodstock performance is often mythologized as a kind of paradigmatic moment of counter-culture appropriation, of culture jamming fifteen years before anyone had thought of using the term ‘culture jamming’. Here was a noble and patriotic song being roughly hewn back into the militaristic fires from whence it came, Hendrix’s bloody tableau mirroring the war of 1812 that served as inspiration for Francis Scott Key’s original poem.

But it’s not usually remarked on that “The Star Spangled Banner” was actually a British song to begin with. The tune was first known as “To Anacreon in Heaven”, and was written by organist John Stafford Smith as a constitutional song for the Anacreontic Society, a British gentlemen’s club dedicated to “wit, harmony, and the god of wine.” Despite the notorious difficulty in singing the Anacreontic melody (one wonders if the Bacchanalian nature of the society made the task even less viable), the tune was a popular fit for a number adaptations (known as contrafactums) at the time, of which “The Star Spangled Banner” was only one. It also served as a vehicle for Robert Paine’s ode, “Adams and Liberty” in the late 18th century, for example.

The themes of appropriation and reappropriation are perhaps the one constant in the life of “The Star Spangled Banner”. Whoever knows what Hendrix meant when he played it at Woodstock. It does seem likely, after all, that there was some kind of protest meant, but if Hendrix saw what happened to Feliciano a year earlier, he’d have good reason not to push it further.

Curiously, Hendrix himself never said that the performance was meant particularly as a protest. In fact, he never really explained the meaning of the performance at all, except for a brief remark at a press conference a few weeks later.

“We play it the way the air is in America today,” Hendrix said. “The air is slightly static, don’t you think?”

*

One of Spec Ops’ central villains used to write for Rolling Stone. Robert Darden, a bearded, Hawaiian-shirt wearing reporter taunts the player over a city-wide broadcast system for much of the game, earning him the nickname of the ‘Radioman’. He also has pretty good taste in music, and through several key scenes in the game blasts out Deep Purple, Martha and the Vandellas, and The Black Angels.

Having an antagonist like Radioman allows music to come to the fore in The Line. Rock music is often blasted diegetically through the game’s Dubai, sometimes as a complement to the action and sometimes as a counterpoint, but always as a reminder of the foreignness of the American presence in Dubai. The music writes over the Emirati landscape, reminding players that it is American against American in this game, and that Dubai is only present insofar as it is an immutable reminder of America’s foreign entanglements. This is, by and large, a game about America and American culture: whatever the problems are of sequestering Dubai for thematic ends, The Line is not interested in it as much more than an emblem.

In one early sequence that announces the game’s engagement with popular culture, a lengthy firefight is set to Deep Purple’s 1968 hard rock hit, ‘Hush’. In the context of The Line, ‘Hush’ should act as an ironic counterpoint to the action—“Hush, hush, I need her loving,” sings Rod Evans, “But I'm not to blame now.” When Alfonso Cuarón used the same song in his terrifyingly bleak Children of Men, the Los Angeles Times called it “a sly lullaby for a world without babies.” When Spec Ops makes other similar allusions with its music, as with Martha and the Vandellas’ 1965 Motown classic, ‘Nowhere to Run’, the point is clear enough, even erring on overstating things. “Got nowhere to run to, baby,” runs the Holland-Dozier-Holland lyrics as the bullets fly over our protagonists, “Nowhere to hide.”

But right then, in the heat of the Deep Purple battle, the unsettling point is lost in the haze of cover-to-cover sprinting and pop-and-stop shooter mechanics. The lyrics might say one thing, but the cutting backbeat and the powerful bass line says something else entirely. All this shooting, this strategy, this chaos, this music—this is a little bit cool.

“Hey, you guys hear music?” asks one of The Line’s protagonists.

“Who cares?” answers our character. “Just shut up and keep fighting.”

The tension between critical commentary and surface level enjoyment lingers throughout The Line. When, later in the game, a slow-motion escape from a missile blast is set to Verdi’s ‘Dies Irae’, this unease is amplified. Like the Wagner helicopter attack sequence from Apocalypse Now (which was undoubtedly the scene’s inspiration, as the blast comes from a helicopter here, too), The Line runs a real risk of its intended commentary being literally drowned out by a one hundred person orchestra. The ironic juxtaposition of dead white European classical composers with macho violence is subsumed by the grandiloquent power of Verdi and Wagner, a tension that Coppola played with in Apocalypse Now but that has eventually been defeated by Hollywood iconography. Though Wagner-and-the-helicopters has now entered into the pop culture lexicon, how often is it used to invoke the madness and the masculinity of war, as intended? How often is it instead used to illustrate military elegance and the iconographic power of the Vietnam war?

This is the fundamental problem of The Line, one that is clearly reflected in its use of music. Does it matter that the game offers up a heartbreaking critical commentary on war and videogames, if from moment-to-moment, all I can do is enjoy the mayhem? Does it matter that my enemies are screaming at me that I’m a murderer, that their radio chatter becomes increasingly fearful of me as I move forward through their soldiers like some sort of nightmarish Superman, if the game has also been perfectly calibrated to give me pleasure from discharging my weapon into the faces of oncoming, depersonalized enemies?

“Shut up and keep fighting.” The context of that terse comment is one of maintaining control in the heat of battle, of blocking out pain and trauma until later, when it might be safe to reflect on your horrific deeds. Yet it could equally also apply to the naive player, the kind not interested in The Line’s plot but in its thrilling action; not so much a remark on a lack of time as a lack of care. “Shut up and keep fighting.”

*

Of course, the simple fact that players are not likely to miss The Line’s critique does not automatically mean anything at all. Earlier this year, the Australian army released the Chief of Army’s Reading List for soldiers. Conspicuous on the traditional list were books like Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 and Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five, while films included the likes of David O. Russell’s Three Kings, Ken Loach’s The Wind that Shakes the Barley and of course, Apocalypse Now.

The presence of these works on such a list appears, at first, to be inexplicable. What use could Catch-22—a book that coined the anti-Vietnam war slogan, “Yossarian Lives!”—have for army bureaucracy? Why would army officials want soldiers to watch a film like Three Kings, a film that tracks three soldiers’ attempts to steal gold in the wake of the first Gulf War, a film that was described by the Los Angeles Times as “one of the defining antiwar films of our time, a scathing and sobering chronicle of U.S. misadventures in the Middle East”?

In commenting on the success of The Hurt Locker at the 2010 Oscars, Slovoj Žižek offers this: “In its very invisibility, ideology is here, more than ever: we are there, with our boys, identifying with their fear and anguish instead of questioning what they are doing there.”

Perhaps it is impossible to make an anti-war film. Perhaps there is always the possibility that despite context and framing, the exhilaration and terror of combat will always translate into romance for some. The strategy for most so-called anti-war films is still one of audience identification: here are innocent characters, thrown into a terrible scenario so beyond the realms of civility that we feel for them even as they commit heinous acts.

Even when characters are allowed some complexity, or are even pushed to become monsters, we can still see glimmers of our own collective guilt, our tortured souls played out within these people. There but for the grace of God, go I. Anti-war films are the best recruitment tool for fascists who still believe in their own soul.

And so it goes with The Line. No matter how hard the game tries in being anti-war, or even just to be a confronting critique of its genre, it never fails to also re-articulate the pleasures of the military videogame. Subversion is frequently too enormous, too clumsy, and too delicate a task to undertake meaningfully. Too much is pulled in too many directions; too many elements left unaltered. For every player who gets The Line’s Joseph Conrad references, another handful will simply find pleasure in the game’s tactical gunfights.

Subversion, especially in a medium as commercial and unwieldy as the videogame, is an imprecise art.

*

In 2000, the virtuoso guitarist Joe Satriani opened a Baseball match between the Giants and the Mets with his own homage to Hendrix’s performance of ‘The Star Spangled Banner’, a moment that was in turn recreated in last year’s Moneyball. His version was nearly identical to Hendrix’s, even down to the guitar tone and layering of effects. What was not recreated, however, was the crushing, distorted sounds of machine guns, bombs, and cries of terror. Why, after all, would you bring that sort of subject matter up at a baseball match, a time where national disgraces are usually tactfully concealed behind layers of professional competition?

What Satriani was left with was just a somewhat stylish, metal-cool version of the American national anthem. He played it, the audience stood, some sang along, and most cheered when it was over. Hendrix was back in the patriotic fold, the ambiguous and potentially subversive elements of his performance smoothed over by a modern rock star. There were no rough edges anymore.

Somehow, between 1969 and 2000, the context of playing the anthem on an electric guitar had shifted from disruption to celebration, from national anthem to rock anthem. There’s something telling about the fact that the only videogame to feature Hendrix’s version of “The Star Spangled Banner” before The Line was Guitar Hero 2.

Look at this page on Answers.com:

The question: “Did Jimi Hendrix mean to dishonor the Star Spangled Banner?”

The answer: “He would never disrespect our country. He played the song that way to honor the troops that were fighting in Vietnam.”

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women: too hard to animate for Assassin’s Creed, but pretty easy to be horrible to

With some of the building discussion about the upcoming Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate, which will, for the first time, allow you to play as a man and a woman (siblings, we’re told), it occurred to me that there wasn’t much follow up regarding the last game’s treatment of women.

Assassin’s Creed: Unity, you’ll recall, made headlines when a Ubisoft creative director claimed that women weren’t playable in the game because a woman protagonist would be too hard to animate. I wrote something at the time in response to that, and how Ubisoft were complicit in the erasure of women from the French Revolution.

So now the game has been out for almost a year, how’d they go? How were women, especially the key women of the French Revolution, depicted in Assassin’s Creed: Unity?

Not well. In fact, quite a bit worse than not well.

Let’s take a look at some of the women in the game. Spoilers follow.

Elisé de La Serre is the central fictional woman of the game, the love interest of Unity’s protagonist. She’s reasonably clearly sketched out, has her own agency, her own motivations. She also dies completely unnecessarily at the game’s climax because... because why? To graft some much-needed actual emotion into the game’s lifeless, characterless male protagonist? Ugh.

There’s also this lecherous scene featuring the Marquis de Sade. Because it’s ‘edgy’, I guess?

Marie Antoinette, almost certainly the most famous woman of this period of French history, very briefly appears in a co-op mission and for many players therefore would’ve been entirely absent.

Charlotte Corday, the most famous non-fictional assassin from the entire revolutionary period, is in the game. Great! But she’s not a major character or an assassin colleague, as many had thought she might be. In fact, you help arrest Corday in a murder-mystery side-mission. That’s right: you, master assassin, track down and turn in the best assassin from the French Revolution to the authorities because... again, I’m lost for a reason here.

And finally, how about Olympe de Gouges, the author of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen?

Well, she’s also in the game. You retrieve her guillotined head for Marie Tussaud.

You honestly couldn’t make this stuff up. When the ‘too difficult to animate’ controversy hit, you’d think Ubisoft would’ve scrambled to make sure what depictions of women they had in their game were at least not going to further fuel the flames.

Instead, we have the three most important women from the period as barely present, a severed head, and as a murderer to apprehend, while the central fictional woman of the game’s plot ends up being killed in order to cheaply import narrative heft.

You’ll excuse me if I’m not yet hopeful that Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate is going to do any better.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some things I should've said

Here’s a bunch of things I’ve wanted to say about the fallout from this piece but have largely thought weren’t worth stooping to address. I now feel like it’s important to have a record of this stuff going into the future, something more than a collection of tweets to point at and say—what happened here was wrong.

Pretty much all the ‘gamers are dead’ articles (not to mention a huge amount of mainstream press subsequent to gamergate’s eruption) cite either Leigh Alexander or I, who posted similar articles within the space of a few hours. Most of them cite us both. But Alexander has been a target of harassment, and with a few pitiful exceptions, I haven’t. Wonder why that might be?

What harassment has stemmed from my post, however, has been those people choosing to pursue Adrienne Shaw, a woman whose research I referred to in my article. There are YouTube videos and imageboard threads trying to pick apart Shaw and her research, to establish a conspiracy that would mean that I had an ulterior reason for quoting her. Shaw seems to have dealt with this attention with a lot more aplomb than I would’ve—she’s a very impressive person.

Let me just restate that: while Leigh Alexander has received harassment for her article and I have not, a woman whom I merely referred to in my article has received harassment and I have not.

For the record I don’t know Shaw at all, but ironically, since the harassment began we’ve exchanged a number of bemused tweets about the whole thing, and she seems like a lovely person. I like Shaw a lot and now hope to meet her one day.

Also if you’re looking for a games academic who proclaimed the death of the gamer identity much earlier than any of us did, then I was recently reminded that the scholar you’re looking for is Ian Bogost. But, oh, he’s a dude, so, yeah. Also the thing he wrote was in a book, so you’d have to read to discover it.

Oh, and the gamejournopro google group that gamergate folk were hoping would prove evidence of a conspiracy to circulate ‘the death of gamers’ articles? Not only was I not on it, but I had never even heard of it until gamergate.

Also I’ve never spoken to the majority of those who wrote ‘death of gamers’ followups. I haven’t even read the vast majority of these pieces. I see these imgur MS paint jobs with red lines between my tumblr and articles I’ve never even seen, by people I’ve never heard of, and all I can do is roll my eyes.

For that matter, those journalists and commentators who have responded negatively to my piece seem also unable to perform basic research. Most refer to me as an academic, or ‘obscure academic’ as in the case of this embarrassing Slate article. In fact, one google search would’ve revealed that I’ve been a journalist for as long as I’ve been an academic (probably longer), and that in 2013 I won an award for my journalism, which would surely strengthen their case against me and the ‘biased’ press.

Speaking of basic research: some gamergaters seem to think I was once (or possibly still am) the Chair of DiGRA Australia. This is because when you search ‘dan golding digra’ you get a link to the DIGRAA homepage with a truncated hit with ‘chair … dan golding’. This is because I chaired a panel at the DiGRAA conference which lasted 30 minutes. Big difference between chairing an organisation and chairing a 30 minute panel, but again, I suppose that would mean that we were dealing with people who had read beyond a truncated google search result. I’m not even a member of DiGRA. I’ve never been a member of DiGRA. Seriously.

I’ve seen some gaters describe my rationale for writing my post as stemming from seeing ‘my friend’ Zoe Quinn get harassed. I think Zoe is amazing, but I’ve never met her, never emailed her, never had a twitter conversation with her to the best of my memory. As far as I know she doesn’t know I exist. That’s pretty much the same for all of the rest of gamergate’s targets. Don’t know Leigh Alexander, don’t know Anita Sarkeesian, don’t know Brianna Wu. The last interaction I had with Jenn Frank before gamergate ended with her calling me an asshole, actually, though I like Jenn a lot and really hope to meet her someday.

According to this piece of analysis, my article is actually the only one of the supposed fleet of ‘death of gamers’ article that actually uses that phrase. I have to agree with the author’s assessment: to get outraged over my claiming of the death of an identity, or to claim it as evidence of a harassment campaign aimed at gamers, is not only patently absurd but also reveals an inability to grasp a common rhetorical technique. To those of you who have mounted a campaign based on this supposed harassment: you misunderstood something pretty basic. You got it wrong, and you should feel embarrassed of how deeply the scale of your response reveals this.

I did like Christina Hoff Sommers’ description of me as a pontificating academic, though (or was that a hipster with a cultural studies degree? I can’t remember).

Some other things I should’ve said more loudly:

I can’t believe how incredible Anita Sarkeesian, Brianna Wu, Zoe Quinn, and many more besides have been through all this. The way they have remained steadfast in the face of grossness means they will forever remain heroes to me, and they should be the heroes of the entire videogame industry. It is also my resolution that they will not have to work alone and unsupported.

The most important response to an event like gamergate is for those with the power to do so to work to institute structural changes that ensure that the circumstances that allowed gamergate to occur are eliminated. Gamergate was the ultimate and possibly unavoidable expression of years of structural imbalance and bias within the entirety of games culture, from fandom to marketing to business to development to the press. What needs to happen now is a structural response to that imbalance: more support for women and marginalised groups, more visibility for their work (in the present and in history), more coverage, more women CEOs and board members at games companies, more marketing not addressed at boys, more normalisation of a diverse picture of what it means to like and play and make videogames.

We also need structures in place to ensure that disenfranchised young men in videogame culture do not turn to opportunistic conservatives with open arms and bared teeth. I worry that that horse has bolted, though.

The ubiquitous straight white male gamer is a bedtime story that videogame culture has told for far too long. It is now time to dismantle it at its base. That’s what I’ll be doing, anyway. The only response to such rampant misogyny is more equality, more feminism, more diversity in the most visible elements of videogame culture, more championing of marginalised voices. More, more, more.

431 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

This is definitely a thing I'm pretty proud of putting together.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I finally bothered figuring out how to make gifs from films. You've been warned, act accordingly.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

In videogames, does sexism begin at the top?

While continuing to think about the root causes of sexism, misogyny and the systematic and deliberate exclusion of women in the games industry, I decided to try a little experiment. I took all the games featured in the latest Feminist Frequency ‘Tropes Vs Women in Videogames’ video – games that have been identified and selected as containing poor representations of women. Then I looked up their publisher’s management, board, or founders – whoever seems to be at the top of the chain.

This is an experiment, it’s not scientific and it’s possible I might have made some errors – but what we have here certainly paints a picture. You'll see I've noted in italics after each group the ratio of women at the top of these companies.

Here’s what I found:

Ubisoft

Alain Corre, Executive Director, EMEA

Christine Burgess-Quémard, Executive Director, Worldwide Studios

Yves Guillemot, Co-founder and CEO

Laurent Detoc, Executive Director, North America

Serge Hascoët, Chief Creative Officer

Verdict: One woman from five.

Deep Silver – Koch Media

Dr. Klemens Kundraitz, CEO

Dr. Reinhard Gratl, CFO

Stefan Kapelari, COO

Verdict: No women from three.

Bethesda, id Software, Arkane Studios – ZeniMax Media

Robert A. Altman,

Chairman & CEO

Ernest Del,

President

James L. Leder,

EVP & COO

Cindy L. Tallent,

EVP & CFO

J. Griffin Lesher,

EVP Legal & Secretary

Denise Kidd,

SVP Finance & Controller

Verdict: Two women from six

BioWare – Electronic Arts

Leonard S. Coleman - Director

Jay C. Hoag - Director

Jeffrey T. Huber - Director

Vivek Paul - Director

Lawrence F. Probst III - Chairman Of The Board

Richard A. Simonson - Lead Director

Luis A. Ubiñas - Director

Denise F. Warren - Director

Andrew Wilson - Director, CEO

Verdict: One woman from nine

Lionhead – Microsoft Studios

I can’t find an extensive official listing for Microsoft Studios anywhere, though Phil Spencer is the Head of Microsoft Studios, Phil Harrison is Worldwide Corporate Vice President, and Yusef Mehdi is Head of Business Strategy and Marketing at Xbox. Microsoft has a stated policy and strategy to increase diversity. The Microsoft board of directors includes two women (Dina Dublon and Maria M. Klawe) out of ten.

Sony Santa Monica – Sony

Kazuo Hirai, President and CEO Sony Corporation

Kunimasa Suzuki, President and CEO, Sony Mobile Communications

Michael Lynton, CEO, Sony Entertainment, Chairman and CEO, Sony Pictures Entertainment

Amy Pascal, Co-Chairman, Sony Pictures Entertainment Chairman, Sony Pictures Entertainment Motion Picture Group

Doug Morris, CEO, Sony Music Entertainment

Martin Bandier, Chairman and CEO, Sony/ATV Music Publishing

Andrew House, President and Group CEO, Sony Computer Entertainment Inc.

John Kodera, President, Sony Network Entertainment International

Dieter Daum, CEO, Sony DADC Global

Verdict: One woman from nine.

IO Interactive, Eidos Interactive – Square Enix

Yosuke Matsuda, President and Representative Director

Philip Rogers, Director

Keiji Honda, Director

Yukinobu Chida, Director

Yukihiro Yamamura, Director

Yuji Nishiura, Director

Verdict: No women from six.

Activision

Robert J. Corti – Director

Brian G. Kelly – Chairman of the Board

Robert A. Kotick – Director. President and Chief Executive Officer

Barry Meyer – Director

Robert J. Morgado – Director

Peter Nolan – Director

Richard Sarnoff – Director

Elaine Wynn – Director

Verdict: One woman from eight.

CD Projekt

Adam Kiciński – President, Joint CEO

Marcin Iwiński – Co-founder, Joint CEO

Piotr Nielubowicz – Member of the Board, CFO

Adam Badowski – Member of the Board, Studio Head

Michał Nowakowski – Member of the Board, SVP Business Development

Katarzyna Szwarc - Chairwoman of the Supervisory Board

Piotr Pągowski - Deputy Chairman of the Supervisory Board

Cezary Iwański - Supervisory Board Member

Grzegorz Kujawski - Supervisory Board Member

Maciej Majewski - Secretary of the Supervisory Board

Verdict: One woman from ten.

Nintendo

Satoru Iwata, President

Genyo Takeda, Senior Managing Director

Shigeru Miyamoto, Senior Managing Director

Tatsumi Kimishima, Managing Director

Shigeyuki Takahashi, Director

Satoshi Yamato, Director

Susumu Tanaka, Director

Shinya Takahashi, Director

Hirokazu Shinshi, Director

Naoki Mizutani, Outside Director

Verdict: No women from ten.

2k Games, Rockstar – Take-Two Interactive Software

Strauss Zelnick, Chairman and CEO

Karl Slatoff, President

Lainie Goldstein, CFO

Michael Dornemann, Lead Independent Director

Robert Bowman, Director

J Moses, Director

Michael Sheresky, Director

Susan Tolson, Director

Verdict: One woman from eight.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

The End of Gamers

The last few weeks in videogame culture have seen a level of combativeness more marked and bitter than any beforehand.

First, a developer—a woman who makes games who has had so much piled on to her that I don’t want to perpetuate things by naming her—was the target of a harassment campaign that attacked her personal life and friendships. Campaigns of personal harassment aimed at game developers are nothing new. They are dismayingly common among those who happen to be women, or not white straight men, and doubly so if they also happen to make the sort of game that in any way challenge the status quo, even if that challenge is only made through their very existence. The viciousness and ferocity with which this campaign occurred, however, was shocking, and certainly out of the ordinary. This was something more than routine misogyny (and in games, it often is routine, shockingly). It was an ugly spectacle that should haunt and shame those involved for the rest of their lives.

It’s important to note that this hate campaign took the guise of a crusade against ‘corruption’ and ‘bias’ in the games industry, with particular emphasis on the relationships between independent game developers and the press.

These fires, already burning hot, were further fuelled yesterday by the release of the latest installment in Anita Sarkeesian’s ‘Tropes vs. Women in Video Games’ video series. In this particular video, Sarkeesian outlines “largely insignificant non-playable female characters whose sexuality or victimhood is exploited as a way to infuse edgy, gritty or racy flavoring into game worlds. These sexually objectified female bodies are designed to function as environmental texture while titillating presumed straight male players.” Today, Sarkeesian has been forced to leave her home due to some serious threats made against her and her family in response to the video. It is terrifying stuff.

Taken in their simplest, most basic form, a videogame is a creative application of computer technology. For a while, perhaps, when such technology was found mostly in masculine cultures, videogames accordingly developed a limited, inwards-looking perception of the world that marked them as different from everyone else. This is the gamer, an identity based on difference and separateness. When playing games was an unusual activity, this identity was constructed in order to define and unite the group (and to help demarcate it as a targetable demographic for business). It became deeply bound up in assumptions and performances of gender and sexuality. To be a gamer was to signal a great many things, not all of which are about the actual playing of videogames. Research like this, by Adrienne Shaw, proves this point clearly.

When, over the last decade, the playing of videogames moved beyond the niche, the gamer identity remained fairly uniformly stagnant and immobile. Gamer identity was simply not fluid enough to apply to a broad spectrum of people. It could not meaningfully contain, for example, Candy Crush players, Proteus players, and Call of Duty players simultaneously. When videogames changed, the gamer identity did not stretch, and so it has been broken.

And lest you think that I’m exaggerating about the irrelevance of the traditionally male dominated gamer identity, recent news confirms this, with adult women outnumbering teenage boys in game-playing demographics in the USA. Similar numbers also often come out of Australian surveys. The predictable ‘what kind of games do they really play, though—are they really gamers?’ response says all you need to know about this ongoing demographic shift. This insinuated criteria for ‘real’ videogames is wholly contingent on identity (i.e. a real gamer shouldn’t play Candy Crush, for instance).

On the evidence of the last few weeks, what we are seeing is the end of gamers, and the viciousness that accompanies the death of an identity. Due to fundamental shifts in the videogame audience, and a move towards progressive attitudes within more traditional areas of videogame culture, the gamer identity has been broken. It has nowhere to call home, and so it reaches out inarticulately at invented problems, such as bias and corruption, which are partly just ways of expressing confusion as to why things the traditional gamer does not understand are successful (that such confusion results in abject heartlessness is an indictment on the character of the male-focussed gamer culture to begin with).

The gamer as an identity feels like it is under assault, and so it should. Though the ‘consumer king’ gamer will continue to be targeted and exploited while their profitability as a demographic outweighs their toxicity, the traditional gamer identity is now culturally irrelevant.

The battles (and I don’t use that word lightly; in some ways perhaps ‘war’ is more appropriate) to make safe spaces for videogame cultures are long and they are resisted tempestuously, but through the pain and suffering of people who have their friendships, their personal lives, and their professions on the line, things continue to improve. The result has been a palpable progressive shift.

This shift is precisely the root of such increasingly violent hostility. The hysterical fits of those inculcated at the heart of gamer culture might on the surface be claimed as crusades for journalistic integrity, or a defense against falsehoods, but—along with a mix of the hatred of women and an expansive bigotry thrown in for good measure—what is actually going on is an attempt to retain hegemony. Make no mistake: this is the exertion of power in the name of (male) gamer orthodoxy—an orthodoxy that has already begun to disappear.

The last few weeks therefore represent the moment that gamers realised their own irrelevance. This is a cold wind that has been a long time coming, and which has framed these increasingly malicious incidents along the way. Videogames have now achieved a purchase on popular culture that is only possible without gamers.

Today, videogames are for everyone. I mean this in an almost destructive way. Videogames, to read the other side of the same statement, are not for you. You do not get to own videogames. No one gets to own videogames when they are for everyone. They add up to more than any one group.

On some level, the grim individuals who are self-centred and myopic enough to be upset at the prospect of having their medium taken away from them are absolutely right. They have astutely, and correctly identified what is going on here. Their toys are being taken away, and their treehouses are being boarded up. Videogames now live in the world and there is no going back.

I am convinced that this marks the end. We are finished here. From now on, there are no more gamers—only players.

EDIT: This post does not do nearly enough to acknowledge that women have been playing, making, and thinking about games throughout game history. The stats that I quote above about adult women outnumbering teenage men could fairly be read as an erasure of this fact and for this I apologise unequivocally. Women are here now and they have always been here, but they are often deliberately made invisible for cultural, financial, and bigoted reasons. It is everyone’s job—perhaps mine especially given this post—to reverse this in history, and the present. Perhaps the most important lesson to be taken from all of this is that women's voices are more important than ever: something that this post does disappointingly little to address.

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Those weird Mario Kart 8 characters are really avant-garde composers

Here's a great article from the A.V. Club reviewing all 30 characters in the latest Mario Kart.

Unfortunately, however, it writes off 'The Koopalings' as merely making up the numbers, and goes on to hypothesise about Morton's status as a reference to the talk show host, Morton Downey Jr.

They're wrong. The Koopalings are actually a set of avant-garde classical and film composers. Let me show you.

Morton Kooper Jr is actually Morton Feldman

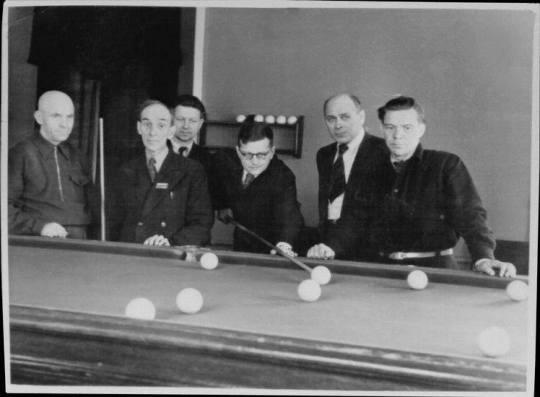

Here's Morton with his namesake, the brilliant 20th century composer and friend and contemporary of John Cage, Morton Feldman. Feldman was a man of striking appearance, as you can see, which has perhaps rather cruelly been translated into his Koopa version above. In contrast to his sheer size (Feldman was six feet tall and 300 pounds), he wrote music of extraordinary quietude and stillness. My favourite work of his is Rothko Chapel, written to mourn his friend and artist Mark Rothko.

Wendy is actually Wendy Carlos

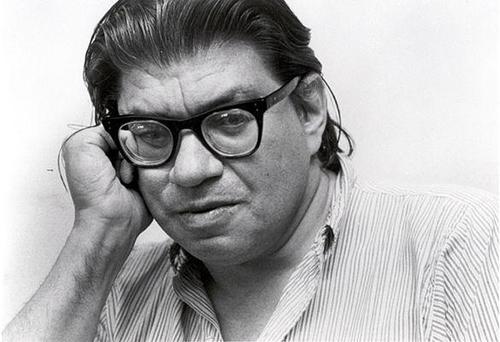

Here's Wendy Carlos, above, in her amazing studio in, I think, probably the 1980s. Carlos was (and is!) a pioneer of synthesised music, writing Switched-On Bach in 1968, a groundbreaking use of the Moog synth, and winning three Grammies for her trouble. She also wrote the amazing scores for A Clockwork Orange, The Shining, and TRON. Here's my favourite piece of hers, the reworking of Mussorgsky's 'Dies Irae' for the opening credits of The Shining.

Roy is Roy Webb

Roy Webb wrote the music for hundreds of Hollywood films between the 1930s and 1950s, specialising in a kind of dark and suspenseful film noir and horror mode. His most famous scores are Hitchcock's Notorious, the beloved Marty, and the somewhat lacklustre biography Houdini.

Ludwig is, well, yeah

`

[After a few queries from people, I should probably just note that I know that most of these are patently false (Roy is probably named after Roy Orbison, for example) but I prefer to believe this version because isn't it more fun to believe Nintendo named these fairly useless characters after amazing composers?]

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

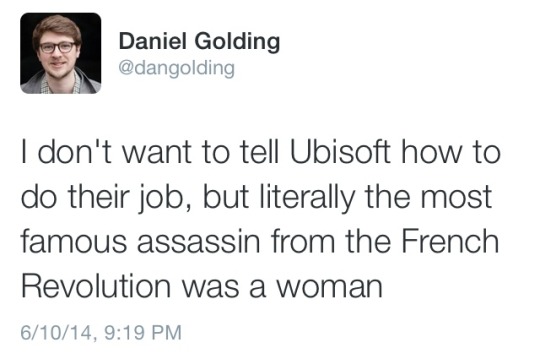

Notes on Ubisoft's Charlotte Corday

It's been a weird few days. A tweet of mine, what I thought was a completely mild, innocuous tweet, took off and has so far been retweeted something like 1800 times. A screenshot of that tweet was featured in a tumblr post that so far has about 140k notes.

In the tweet I'm talking about Charlotte Corday, of course. She's the assassin that killed Marat and whose murderous act inspired the most famous piece of art to come out of the revolutionary period, David's The Death of Marat (1793).

I've never been associated with anything like these numbers before, and, as you can imagine, I've been receiving lots of eloquent and polite correspondence on twitter as a result. Nothing as bad as if I happened to be a woman saying the same thing, of course. I've mostly ignored it, but I wanted to do something to catalogue some thoughts in response.

So here is an encyclopaedia of ignorance that I've seen so far, and some unorganised thoughts in reply.

You don't know anything about Assassin's Creed. In previous games you don't play as a real person. I know. No-one's suggesting you play as Charlotte Corday (though that would be cool, wouldn't it?). The point is that Ubisoft have assumed that a male assassin is the default, whereas the actual history of the period suggests the complete opposite. Maybe Ubisoft should be forced to justify why they've chosen a male assassin over the more logical and historically relevant decision to play as a woman. Why have they reorganised history?

Ubisoft can't be sexist. In Assassin's Creed: Liberation, you played as not just a woman, but a non-white woman too. I do know this. I briefly got to know the writer of Liberation, Jill Murray, at an event we both spoke at earlier in the year, and I can't imagine a smarter choice of writer to be involved in the series. I hope she is doing some great work on this very point behind the scenes right now. But you know the fact the AC games have had a woman protagonist before actually makes this decision—and its accompanying excuse—worse, don't you? It's not a precedent which excuses all subsequent offences. It's a building block from which to move forward—and a pillar that proves that excuses of cost or workload when it comes to playable women are laughable.

Charlotte Corday will probably turn up as a character in the game. Yep, it seems likely. That doesn't change anything, really. I just hope that we don't assassinate Marat with her looking on, as we rode Paul Revere's horse for him in Assassin's Creed III. That would, for obvious reasons, be bad.

Because Charlotte Corday is famous/was caught, she wasn't a good assassin. Or, as one person tweeted at me this morning, she apparently wasn't an assassin at all (for reasons best kept to himself and his six followers). This actually really concerns me, because it suggests that there are people out there that truly believe that there have been real Assassin's Creed-style assassins throughout history, the kind that successfully knock off dozens, if not hundreds of important targets and slip away into the crowd, or parkour off into the distance, to be unrecognised both by their contemporaries and by history. Seriously, if you believe this—especially about such a well-documented and widely-studied era as the French Revolution—then I implore you to pick up a book and read, and expand your understanding of history beyond the Assassin's Creed games. I love the AC games. I have at least 20,000 words on them through my PhD thesis. They are fantasies of history. Real assassination is utterly unromantic and flawed. Charlotte Corday is the image of a real assassin—a newcomer to violence, working for all intents and purposes by herself, who either intended to be caught or understood it as an inevitability, and who planned accordingly so as to make a statement. Ezio is not reality.

Most importantly of all: by creating an all-male-protagonist French Revolution videogame, Ubisoft have entered a long-held tradition of downplaying or marginalising the role of women in the Revolution. This happened both at the time and through the writing of history subsequently. After her execution, Charlotte Corday was examined to find out if she was a virgin—if she had been 'sharing her bed' then surely we would find a man's hand behind the assassination (this was not the case). Could a woman really have come up with this plan herself?

Women were repeatedly denied rights, both before the revolution, during it, and after it. The famous Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen remains silent on women, despite a preceding petition calling for equal rights for women. This situation lead to Olympe de Gouges' complex and witty Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen, which is ironically dedicated to Marie Antoinette, and declares (remember, this is 1791) that "This revolution will only take effect when all women become fully aware of their deplorable condition, and of the rights they have lost in society."

Groups like the Society of Revolutionary Women were formed, and in 1793, outlawed and abolished by the Jacobin government. Then, the Napoleonic Code of 1804 reinforced French women's status as second-class citizens.

And of course, then came the many conservative historians who had either an interest in downplaying the role of women, or whose privilege meant it was a question easily ignored. As Shirley Elson Roessler writes in her excellent Out of the Shadows: Women and Politics in the French Revolution, 1789-1795,

The topic of women's participation in the French Revolution has generally received little attention from historians, who have displayed a tendency to minimize the role of women in the major events of those years, or else to ignore it altogether. In the nineteenth century those who did attempt to deal with the topic chose to approach it with an emphasis on individual women who had for some reason attained a degree of notoriety.

So you see that even a focus on someone like Charlotte Corday or Olympe de Gouges is a strategy that has been used to downplay the role of women in the broad fabric of the revolution. I'm pleased to see the historically-accurate presence of women in the Assassin's Creed: Unity crowds, in the storming-of-the-palace scenario we were shown at E3—but the fact that women remain unplayable, as a hands-off role, as actors-but-not-protagonists, indicates that Ubisoft is taking a regressive step with Unity, not just for the Assassin's Creed series, not just for the representation of women in videogames, but in representation of the women of the French Revolution.

13K notes

·

View notes

Link

September 28th & 29th, Melbourne, Australia — Freeplay is Australia's independent games festival celebrating the creation and culture of video games.

I guess I'm doing this now, too.

5 notes

·

View notes

Audio

I grew up listening to pretty much only jazz until I was about 14-15. I'm still finishing writing up my thesis and need study music, and I haven't been regularly listening to jazz for a while, so I made a general, introduction-style jazz playlist to remind myself of what I loved.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Hey, I forgot I was also going to use this tumblr to link to things I've written that are published elsewhere. So here's an article I wrote about Halfbrick's new game, Bears vs. Art.

0 notes

Text

Fairfax, it's time to stop talking about Gen Y

Hello, Fairfax. I’m here to tell you you’ve got a problem. It’s time to stop publishing articles about Gen Y.

On the weekend, The Age and the Sydney Morning Herald published another Gen Y article. This one performs the meta-move of remarking on how “Understanding Gen Y – and kicking their teeth in – has become an industry in itself,” and that “The slightly creepy fact is, Generation Y – also known as the Millennials – are probably the most overanalysed and criticised generation, like ever.”

Yes, we’re beginning articles on how difficult Gen Y are now by explaining just how many people have previously remarked on how difficult Gen Y are.

Let’s be clear: this no longer means anything at all. The first Gen Y article published by Fairfax I could find (certainly not the earliest, just the furthest back in the Fairfax archives I could go without succumbing to a full body disgorging) also does this. In 2007—seven years ago—Valerie Khoo asks if Gen Y are unfairly maligned: are they really so despicable? This is apparently a question so compelling that an entire media organisation has dedicated years and thousands of man-hours to answering it. Are Gen Y really so terrible? Are they? ARE THEY? Perhaps with another question—say, less vexing issues like the impacts of man-made climate change on our planet, or the evolution of humans over the course of millennia, or what planets are most likely to sustain life in other galaxies—we might have an answer by now. This is sadly not the case; we are faced with Generation Y, a subject so troubling that it compels us to answer it again and again, like a Sisyphus subeditor with an exciting collection of LOLspeak-based insults.

If you google ‘Fairfax and Gen Y’, or an equivalent, what you’ll find is a resolute gushing of pitiless bullshit, a self-hating (and presumably family-member-loathing) profusion of bile that looks like a media organisation so bereft of ideas that it has to resort to the headmasterly chiding of what might once have been its future core readership.

When I saw John Elder’s article this weekend I tweeted

Fairfax, you have just got to stop with the Gen Y articles. It is now well beyond embarrassing. Just. Stop. S T O P

— Daniel Golding (@dangolding)

March 16, 2014

A few people questioned my reaction. Surely it hasn’t been that bad?

Well, it has.

Here’s what Fairfax have accused Gen Y of over the years:

Gen Y is unable to sustain or understand ‘serious culture’ (whatever that is). “Moronic introspection is celebrated as significant and worthwhile … Young people have lost the capacity to actually know when something is art, and worthy.” Another brick in the wall of Gen Y cultural decline (Christopher Bantick, Jan 7 2014)

Gen Y is responsible for national sports team failures (and, apparently, for the death of original headlines—see below). Why, oh why, does Gen Y not get it? (Peter FitzSimons, October 17 2013)

Gen Y is politically conservative. “My concern is simply that baby Gen-Y appears to be doing nothing except taking duck-faced photos of themselves on Instagram.” Why oh why, Gen Y, are you so nauseatingly conservative? (Alecia Simmonds, Jan 19 2013)

Gen Y is addicted to the internet. “When Melbourne DJ Jade Zoe, 27, goes to sleep at night she sometimes dreams about Facebook.” Gen Y-fi caught in web fixation (Marika Dobbin, Feb 14 2013)

Gen Y is addicted to gadgets. Gen Y finds life goes on without the gadgets (Rachel Olding, May 7 2011)

Gen Y is mounting a cry for help by wearing the infantalising onesie. Poor Gen Y taking us back to square onesie (Annabelle Crabb, August 4 2013)

Gen Y won’t answer the phone. Phone phobia: the latest Gen Y disease (Alexandra Cain, July 19 2013)

Gen Y is a violent generation. “Yet the question still needs addressing: why is generation Y involved in so many violent incidents?” Many ingredients make this gen Y cocktail of violence (Mark McCrindle, Feb 5 2010)

Gen Y are entitled. Gen y: entitled or talented? (Anneli Knight, May 21 2013)

Gen Y are narcissistic.“Wise words, worth encouraging teenagers to pull their earphones out long enough to listen to.” Is this the most narcissistic generation we've ever seen? (Wendy Squires, April 20 2013)

Gen Y is difficult to work with. “Adapting to Generation Y is not appeasing a group of spoiled brats, it's bringing your business up to speed for the coming onslaught of able bodies.” How to work with Gen Y (Kelly Gregorio, Jan 24 2013)

Gen Y are terrible bosses. Help! My Gen Y boss is a nightmare (Tony Featherstone, Sept 18 2013)

Gen Y is killing off the traditional working week. A world under Gen-Y bosses (Caroline James, July 31 2013)

Gen Y is too casually dressed at work. Generation stupidly casual (Paula Joye, June 6 2012)

Gen Y is shunning the traditional working environment. Gen Y shuts door on open-plan century (Catherine Armitage, May 5 2012)

“Gen Y are a nightmare in the workplace” The real problem with Gen Y (Daniel Stacey, July 1 2013)

Gen Y is especially weak in Australia because they did not—wait for it—suffer terribly under a debilitating global financial crisis. “A widely sanctified theory I've heard repeated at pubs, cafes and dinner parties is Gen Y in this country lacks starch because Australia cruised through the Global Financial Crisis and our youth were denied the benefit of tough times to lower their expectations.” Gen Y takes centre stage (Sam de Brito, July 24 2013)

Gen Y are too consumerist (says a publication with an ‘Executive Style’ section). Does Gen Y prefer consumer goods to ideals? (Sarah Burnside, November 7 2013)

Gen Y killed white middle class adventure travel. “People weren't after a holiday, they were after an adventure. But then Generation Y came along.” How Gen Y sucked the fun out of travel (Ben Groundwater, May 15 2013)

Gen Y, when they go travelling, spend important business funds. “Gen Y Australians have been maligned for being self-centred and materialistic. Now, new travel research about the under 34s has revealed that on business trips they are also spendthrifts with the boss's money.” Gen Y travellers spend big with the boss's money (Robert Upe, Nov 27 2013)

Gen Y can’t commit (makes sense, really, given the sheer variety of crimes they have been convicted of by Fairfax so far). Do Gen Y really not understand commitment? (Samatha Brett, August 23 2010)

And even simpler, too:

Is Gen Y that bad? Yes! (Libbi Gorr, April 20 2009)

Gen Y: do we need them? (Vivian Giang, Sept 4 2012)

The Age even boldly ran a series of articles looking at Gen Y after it turned 30 in 2010.

You’d think that, even from this admittedly brief survey—and believe me, this is a brief survey—Fairfax might’ve exhausted the possible range of topics you could write about a single generation. You’d think that a media company might also realise that they could lose a significant section of their audience, if not through the constant insults then at least through the unwavering othering that goes on on their front pages. You cannot treat an entire generation like an alien species and expect them to keep coming back for more.

So, Fairfax, it’s clear you’ve got a problem. It’s okay. We know you’ve had some troubles. We know that your subeditors are addicted to the wild possibilities and ironic text speak offered up by Generation Y-themed headlines and standfirsts. We know you’ve got section editors ready to spring into action when the next Gen Y thinkpiece pitch hits their inbox. It’s okay. They’re eager. We know how it is. You commission one piece by a bitter high school teacher bemoaning today’s youth and suddenly you’re knee-deep in a pile of shit about how your daughter Megan just can’t stay in the same job/degree/career/religion/exchange program/viking metal band and how it’s certainly the fault of her generation’s addiction to the internet (which you publish on)/smart phones (which you target)/social media (which you try and ‘leverage’)/selfies/porn/indulgent parents (that’s you, by the way)/fluffy education (which you received for free)/videogames/Lena Dunham’s Girls/inflexible workplaces/not enough pluck/too many illegal internships/too few illegal internships. It’s such an easy trap to fall into. We know how it is. We’ve been reading.

But it’s time to stop. It’s time to tell the section editors to stop commissioning. It’s time to tell the subeds that there is a whole world of possibility outside of the mocking use of ‘YOLO’ and ‘Why oh why Gen Y’. It’s time to tell them to stop. It has gone beyond embarrassing.

Just stop.

Just.

Stop.

STOP.

S T O P.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reasons to play Action Painting Pro

Action Painting Pro, by Ian MacLarty.

Reasons to play Action Painting Pro

It reminds me of Lode Runner on my Apple LC III

There’s no high score or any real way to compete against others

The responsive music is great with headphones

It reminds me of ApplePaint on my LC III

It’s free, and made by a Melbourne-based developer

There’s a kind of message about the creative process in there, which is interesting

The ‘art’ you turn out is almost always worth looking at for a few seconds before you start again

Reasons not to play Action Painting Pro

???

6 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Film music by decade: 2010-present

1. The Social Network — Hand Covers Bruise — Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross (2010)

I don’t love Reznor and Ross’ music, and The Social Network shouldn’t have won the oscar over Inception, if only for its egregious misuse of Grieg’s ‘Hall of the Mountain King’. But Reznor and Ross’ score did a lot for the kind of twitchy, ambient digital score that has become popular of late. It adds an undercurrent of anxiety to The Social Network that plainly wouldn’t be there without it.

2. Inception — Dream Is Collapsing — Hans Zimmer (2010)

Two notes indelibly associated with a film is some kind of Adorno-esque waking nightmare, and for that alone this score is incredibly significant in the history of film music. It’s also incredibly effective in the film, working to link together the multiple paths of Nolan’s puzzle plot. The sensory overload of this music is, as I’ve written before, the defining sound of this era.

3. Norwegian Wood — Quartertone Bloom — Jonny Greenwood (2010)

Like most of the absolute best of these scores, I struggle to describe Greenwood’s Norwegian Wood. The music aches—that’s about all I’ve got.

4. TRON: Legacy — The Son of Flynn — Daft Punk (2010)

I really didn’t expect to like Daft Punk’s TRON: Legacy score, but it’s a superb amalgam of symphonic and electronic sounds—perhaps the best of such in all of cinema, and at least equal with some of the early pioneers, like Wendy Carlos. Some of the themes are a little simple, yes, but that just betrays their origins in electronic composition, and allows them to combine so fluently.

5. True Grit — The Wicked Flee — Carter Burwell (2010)

Surprisingly enough, the traditional hymn used as the main theme in True Grit has been used in film before—as the song sung in Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter. It’s neatly effective here, though, and serves as a nice counterpoint to contemporary film music trends and proof that subtlety and the basics still work.

6. Super 8 — We’ll Fix It In Post-Haste — Michael Giacchino (2011)

I don’t know if this will show up on Spotify—if not, listen here. It’s the nicest statement of a lovely, E.T.-esque main theme. It’s another intentional throwback to a different era of film music, but Giacchino’s talents help it transcend this.

7. The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo — She Reminds Me Of You — Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross (2011)

One of the nastiest film cues—a menacing bed of synths with gongs (a gamelan, maybe?) idling away on top. The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo isn’t an exceptional film, but it marks another high point for digital film music and adds an element of genuine unpleasantness to the film.

8. The Master — Overtones — Jonny Greenwood (2012)

I really like The Master, but it’s certainly a step down from the magnificent There Will Be Blood and Norwegian Wood. ‘Overtones’ is an excellent, dream-like track, equalled by ‘Time Hole’, which draws in no small way on Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du temps.

9. The Dark Knight Rises — Despair — Hans Zimmer (2012)

Between this and Man of Steel, I don’t see how Hans Zimmer’s current sensory overload mode of composition can be pushed any further. This track contains what I consider to be the apotheosis of the Zimmer melodic-minimalism-and-textural-complexity, with a single statement of the two-note Batman theme lasting more than 30 seconds. When you go back and think about Bernard Herrmann’s objections to leitmotif locking you in for inflexible melodies that last 16 bars, this is kind of incredible.

10. Gravity — Debris — Steven Price (2013)

The ultimate of sound-design-as-score. I don’t think Steve Price’s score is musically interesting, but it’s filmically and aurally hypnotic. It has some faults, even in simple spotting (the film’s opening is a huge mistake, music-wise), but Gravity is dramatically enhanced by the deluge of Price’s undulating, swelling work of digital noise.

#film music#film scores#trent reznor#atticus ross#hans zimmer#jonny greenwood#daft punk#carter burwell#michael giacchino#steven price

7 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Film music by decade: 2000-2009

1. Gladiator — The Wheat — Hans Zimmer and Lisa Gerrard (2000)

Hans Zimmer has been part of three significant film music trends: the mournful-brave martial trumpet melody from the late 1990s (The Rock); the film-music-as-overwhelming-noise of recent times (Inception); and this, with Lisa Gerrard, which established an emotional, wordless woman’s voice as one of the most popular strategies in film music. It was certainly never done better than by Gerrard in Gladiator. The rest of the score is one of Zimmer’s best, and also features beautiful Armenian Duduk and shameless extracts of Holst’s The Planets (for which he was sued) and Wagner’s The Ring (for which he was not).

2. Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring — The Bridge of Khazad Dum — Howard Shore (2001)

I remember not liking the Lord of the Rings scores the first time I saw the film, and I’m not sure why—I think probably I thought the ‘Fellowship’ theme was too simplistic. I was basically as wrong as I’ve ever been. Howard Shore’s Lord of the Rings music is one of the most complex popular musical works since Wagner, with incredible, granular detail in terms of melody, harmony, and texture. This cue illustrates that fairly well, with both some of the heroic music and the guttural musical language for the demonic Balrog doing some good things. But it’s the simplest moment here that means I’ve selected this track over all others from the three films: the mournful voices that accompany the death of Gandalf (from 4:40 onwards) is, I think, the most beautiful music ever recorded for film.

3. Amelie — Le Moulin — Yann Tiersen (2001)

This music is twee, absurdly French, cutesy, and affected. That’s why it’s brilliant, jeez. Tiersen also has an acute ear for melody; these pieces of music would be terrific even if the aural tone was shifted completely.

4. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban — Hagrid the Professor — John Williams (2004)

Imagine the most successful film composer in history, at the peak of his career, being tasked with writing music for the then-most popular blockbuster franchise in the world, and turning round and writing a score mostly for medieval and renaissance instruments and forms. That’s just how strange and unique Williams’ Prisoner of Azkaban is. Built around the ‘Double Trouble’ motif from Macbeth, Azkaban is far and away Williams’ most imaginative score. ‘Hagrid the Professor’ is the most medieval of the film’s cues: other highlights include the La Gazza Ladra-influenced ‘Aunt Marge’s Waltz’; the eccentric big band of ‘The Knight Bus’; an an E.T.-like flying theme in ‘Buckbeak’s Flight’.

5. The Painted Veil — River Waltz — Alexandre Desplat (2006)

Desplat is easily the most consistent composer to emerge in the last decade. Though his music can at times be similar and predictable (an off-kilter piano waltz, you say?), it’s reliably high quality and usually has something to offer, however negligible. He has turned in some surprisingly interesting action scores of late, for example (in the form of the Twilight, Harry Potter, and Argo scores). The Painted Veil is Desplat at his most Satie-like, and probably, at his best.

6. Babel — Deportation/Iguazu — Gustavo Santaolalla (2006)

It feels odd to put ‘Iguazu’ down as being from Babel, given it was originally written for Santaolalla’s (excellent) 1998 solo album Ronroco, and has since been used in The Insider, Yes, Fast Food Nation, and Deadwood. But he apparently adapted it for Babel (there’s some string work in there too), and he won his second Oscar on the back of this piece. It’s certainly an amazing piece of music, wherever its progenitor may be.

7. Casino Royale — Vesper — David Arnold (2006)

Like John Williams, David Arnold is a superb practitioner of pastiche. His style perfectly emulates the lush, melodic style of John Barry’s classic Bond scores (and a few touches of his non-Bond work, like Born Free and Dances With Wolves) while adding a contemporary action edge. Barry’s action music, while great (see On Her Majesty’s Secret Service’s ‘Ski Chase’) wouldn’t stand up in a modern context, but Arnold somehow uses Barry’s musical language to create something that does (‘Target Terminated’ from Quantum Of Solaceis a masterclass in action music). But it’s his lyrical romantic theme for Vesper that I think probably best incapsulates his achievements as a composer here (that, and Quantum of Solace isn’t on Spotify).

8. There Will Be Blood — Open Spaces — Jonny Greenwood (2007)

There Will Be Blood, is, I think, probably the best film score for the last few decades at least (it’s closest competition is Greenwood’s Norwegian Wood from 2010). Greenwood is a rock musician (from Radiohead) turned film composer, but he barely deserves to be in the same category as other pop musicians Danny Elfman and Hans Zimmer. Greenwood’s music here is singularly desolate and emotionally complex. It sounds like a composer who had listened to nothing but Messiaen and Penderecki and Lutoslawski and Xenakis and Ligeti suddenly was allowed to write a film score and do whatever he wanted with it. Impossibly good stuff.

9. The Bourne Ultimatum — Tangiers — John Powell (2007)

Probably the culmination of what Hollywood composers have learnt about writing for action over many decades. Relentlessly masculine polyrhythm.

10. Up — Married Life — Michael Giacchino (2009)

There’s a cacophony of writing on how good this sequence is, and I don’t need to add much to it. This is great music. Taking it away from the film illustrates just how much of the heavy lifting is being done by Giacchino here.

#film music#film scores#Hans Zimmer#Lisa Gerrard#Howard Shore#Yann Tiersen#John Williams#Alexandre Desplat#Gustavo Santaolalla#David Arnold#Jonny Greenwood#John Powell#Michael Giacchino

93 notes

·

View notes