Text

September Event

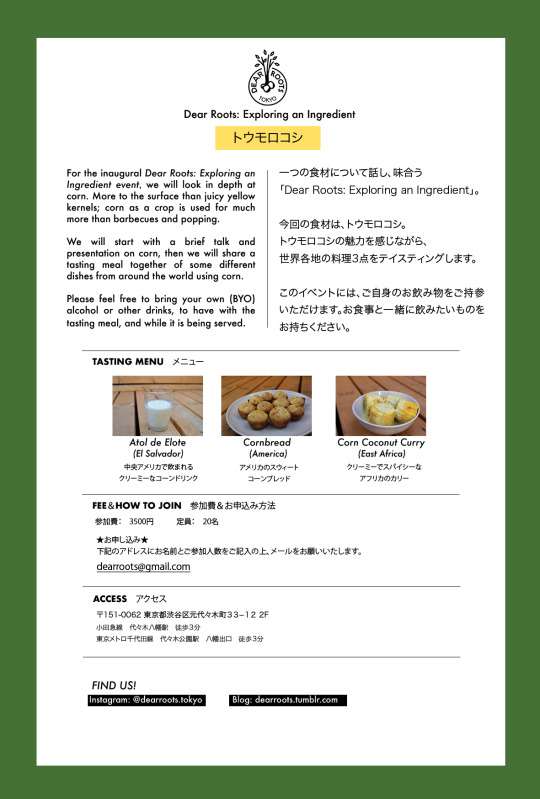

We are excited to announce our next event - CORN. We will be celebrating this juicy yellow crop as our first ingredient of Dear Roots: Exploring an Ingredient series. Did you know that almost all the corn we consume in Japan is imported?

Tasty dishes will be served at the end of the event, and bring your own booze to enjoy! To join, drop us an email: [email protected] or private message our Instagram @dearroots.tokyo (Fee: 3500 yen)

Dear Rootsの9月イベントのご案内です。今回は、トウモロコシのテイスティングです!「Dear Roots: 食材を知る」シリーズの始まりとなります。当日は、世界各地からのトウモロコシ料理をご紹介します。ドリンクもご持参いただけます🎵お申込みはメールにてお願いします:[email protected] (参加費:3500円)

0 notes

Text

Eggs and Japan, 卵と日本

日本人が一年間食べる卵は、一人326個。卵焼きから卵サンドイッチまで、我々が毎日食べている卵はどこから来たのか。今回はSusieが日本で卵が食べられるようになった背景と現代人として考えるべきのこと - 環境を考えたパッケージング、鶏のケージフリーなど - について語る。

Writing & Photos by Susie Krieble

History 歴史

2500年前の素晴らしい発見

Working backwards, eggs haven’t always been as popular in Japan as they are now. Reportedly, a Japanese persons consumes on average 326 eggs a year, which is second or third in the world (depending on how you measure this statistic). This number increased dramatically after World War II when American influences not only on cuisine reached Japan, but advanced refrigeration and other technology for faster (post-lain egg) production. On the cuisine side, in the 1950s, as these Western ideals influenced the rising Japanese economy, eggs became a symbol of health and prosperity. They started being introduced in new ways such as in omelettes or to make mayonnaise and became much more ubiquitous. So how were eggs used in the early days?

Around 2500 years ago, eggs were introduced to Japan from China by way of the Korean Peninsula. Obviously the eggs didn’t arrive on a boat themselves, rather chickens came to Japan 2500 years ago. There is mixed evidence on how eggs were received in this land. Some say they were used for meals and medicine, but that then there was a period in which they were forbidden to be eaten as it went directly against the principles of the Buddhism teachings. Either way, we know that eggs were most commonly linked to wealthy individuals and there weren’t consumed by the common people. Between the 1600s and 1700s, several cookbooks were published which featured recipes using eggs as a starring ingredients, and they started to lose their negative association. Still though, they weren’t super common place.

For a comparison, New Zealand was introduced to eggs in 1773, some 2000 years after Japan got them, but only about half the amount of time elapsed between New Zealand’s founding (1642) and egg introduction, than Japan’s. Further, New Zealanders consume on average only 226 eggs per annum.

Consumption 消費

生で食べる新鮮な卵、そして温泉たまご

In Japan, egg best before dates are extremely conservative. In the summer they are said to last from farm to table about four times less than in winter. While the eggs don’t actually go bad per se, producers need to be extra cautious as so often eggs are eaten raw. In favourites such as kamatama udon (釜玉うどん), tamagokake gohan (卵かけご飯), and sukiyaki (すき焼き), eggs will be eaten before the package date. If you choose to cook the egg, then you don’t need to take as much care.

In fact, there are many uniquely Japanese methods of cooking eggs. A common one is the onsen tamago (温泉卵), whereby the egg is simmered for a long time (traditionally in fresh mountain spring water) still in the shell so that the yolk becomes sticker than the white. Scientifically, the egg consists of three parts - two proteins (in the white, aka albumen) and the yolk. Western traditional soft boiling methods use, as is evident in the name, boiling water. This heats and solidifies the albumen, but doesn’t quite have time to fully penetrate the yolk due to the short boiling time of around 3-4 minutes. If you think about it, the longer you boil an egg, the yolk undergoes many transformations but the white just takes a brisk stroll from liquid to solid with not much changing after reaching solidity pretty early on. So a longer simmering time has more effect on the yolk too and the white takes the same short stroll, but at a more leisurely pace. The white doesn’t fully set, as the temperature isn’t high enough but the yolk becomes custardy (at the right temperature). Good job Japan, you taught us some science.

You will also see eggs balanced on a curry, submerged in miso/other soup - whole or scrambled through, in the convenience stores pre-onsen tamago’ed still in the shell, inside fried bread, as chunks in tartare sauce served with fried chicken (chicken nanban チキン南蛮), whisked into an omelette and folded over rice then topped with ketchup (omurais オムライス), or on skewers and served in izakaya. As a starter for ten.

Plastic プラスチック

パッケージングについて考える

Another Japanese egg anomaly is the packaging. In Japan, you will most often find eggs encased in plastic (like most things in Japan) and then stapled what seems like an unreasonable amount of times, or sealed with a long strip of too-sticky plastic tape. Western egg cartons by comparison are much more sturdy and reusable, and have a groovy self-locking function. Uses for these cartons include soundproofing spaces, growing seedlings, storing jewellery etc. Eggs transported in this fashion is actually much less likely to cause them to break too.

One major difference of note is the opacity. Originally transported in newspaper or in rice hulls, it wasn’t until the dawn of the supermarket in 1967 when a company in Osaka Prefecture (Diamond Foods, Ikeda City) developed the now omnipresent plastic cartons. As eggs needed to be sold on shelves in packaging and Japanese consumers like to see what they are buying, it made sense to use a material like plastic. After some trial and error a design that used triple layering (great, more plastic - however, supposedly the middle layer is recycled) and an octagonal pyramid shape was chosen. This simultaneously suspends the eggs in the packaging while preventing the base of the egg actually touching the plastic and thus reducing the chance to break.

Ethics

鶏はどこから、卵はどこから来るのかを考える

Just one point on the ethics of eggs in Japan. There is so much to explore here, and it’s hard to unravel what is true and what is for show. Most more expensive egg brands focus on the customer, farm hygiene, and lifestyle for the farmers, and often how the chickens are kept is not stated. Some suppliers have shared that it is really hard for chickens to be kept in a big enough space in Japan to be called free range, as the government requirements for a free range farm have enormous dimensions.

In lieu of having this information, I try to find out more about where the farm is, what the chickens are fed, who the farmers are, and making connections with the store where I purchase the eggs. This isn’t much, but a relationship and more knowledge is a good place to start.

Eggs have been greatly developed for the Japanese tastes, and it is hard to go a day without eating at least one. This is a good thing…providing the use of plastic and free range sensibilities start getting noticed!

0 notes

Text

Kimchi - Intro

韓国では大体の人が毎日キムチを食べる。キムチ独特の味もユニークなものだが、これだけ国民の95%が辛い漬物を毎日食べているというのはどこにも無いだろう。今回は、「キムチ特集:Intro」として、韓国出身のジョンミンが韓国のアイデンティティとも言えるキムチについて語り、東京でも買える韓国本場のキムチを紹介する。

Writing & Photo by Jeongmin Kang

朝ごはんでもキムチを食べる韓国人

Korean people eat kimchi everyday - I’m not exaggerating here, even including breakfast. This garlicky, spicy pickled mixture is not only unique in its taste and smell, but also in its intimacy with the daily lives of Korean people. Kyo-ik Hwhang, a renowned Korean food critic, called this relationship “beyond the level of love, but of obsession”. It is very much linked to the national identity, which means that there is very little chance of meeting a Korean who doesn’t eat kimchi – 5% of South Korean population, apparently. It is fascinating how deeply we are rooted to this very distinctive side dish˙. I remember listening to a kimchi theme song when I was growing up. We cannot live without it, as the chorus repeats…

ご飯を食べられるようになった子供はキムチの食べ方を学ぶ

It makes sense, then, that Koreans teach their children how to eat kimchi when they are still young - if we cannot live without it, your child must learn how to survive! In Korea, the average age to start eating red kimchi is around 4-5 years old. When children are too young to handle the spices, parents wash the red chilli spices out for them. Last time I went back to Korea, looking at my friend feeding this to her 3 year-old son, reminded me of my own childhood. When the salt and spices are washed away, a subtle sourness and spiciness are perfect for children. These washed unsalted kimchi can be a perfect filling for rice balls. Mix in the chopped, washed kimchi into cooked rice, drizzle sesame oil and season with salt and pepper.

キムチ専用冷蔵庫って本当?

I was once asked by a friend if Korean people really have a separate fridge for kimchi. Of course, it is true – if you can afford to have two fridges. Most Korean households have a Kimchi fridge, or at least a dedicated drawer to store/mature kimchi. It is a pity that I currently don’t have more space for Kimchi, although we always have a big Tupperware of kimchi, which takes up the whole section of our fridge.

酸っぱくなると本物

Even though it is easier to get hold of kimchi in Japan, compared to European countries, you need to know where to get “real” kimchi. Real kimchi has been fermented and becomes sour as it matures. When we have a kimchi emergency and are not able to travel to Korean supermarkets, we do sometimes buy Japanese kimchi that is available in most shops. Although Japanese Kimchi has a nice sweetness to it, it won’t mature, which means you won’t be able to use it for cooking (technically you can use anything for cooking, but it will be tasteless.) One of the best things about kimchi is that you can use it for cooking in a lot of different dishes or simply eating it as it is. Sour kimchi makes great stews, fried rice, and Korean pancakes (チヂミ) - which I will be introducing in the next few articles.

キムチの賞味期限は、「食べ切るまで」。

I found a great phrase, in Kimchi: Essential Recipes of the Korean Kitchen, that elaborates on how you should consume kimchi: “Kimchi lasts until it’s finished”. I totally agree that there is always a way of using kimchi, even when it smells inedible (if you have somehow managed to reach to this point). Trust me, it is well worth storing a big tub of kimchi in the fridge.

※次の「Kimchi - part 1.」では、酸っぱくなったキムチを使ったレシピを紹介する。

Where to Get "Real" Kimchi in Tokyo:

ジョンミンのおすすめ:「東京で本場のキムチが買えるお店」

1. Kankoku Hiroba (or any other Korean supermarkets in Shin Okubo!): This one is the biggest, and has a variety of kimchi.

韓国広場(新宿区歌舞伎町2-31-11)

2. Kimuchi Kan: It's usually in department stores (デパ地下), which means it's a little pricey but very convenient if you have one nearby. You can get a lot of different kinds of kimchi and other good quality pickles.

沈菜館 (http://www.kimuchikan.co.jp/kimuchikan2.html)

3. Minnano Erika: This is my local one - I was so happy when I found this little shop run by a lovely Korean lady. It is a small shop, so bear in mind that there is a chance that Kimchi is sold-out.

みんなの恵李家(世田谷区4-12-13 ヴェルディ用賀 1F)

0 notes

Text

Taste

Taste, in reality, is not only about how the flavours in the food you are eating present themselves to your nose and tongue, it is about the relationship you have with the food and the supplier to you of the food. Think about something that is really delicious. Put it in your mouth, savour it. Now listen to the chef tell you that they don’t actually know where it came from, and that it is out of season. The chef just thought it was pretty.

Now think about something that is tasty but you wouldn’t go out of your way for it. Listen to the chef tell you that the farmer is a third generation farmer from a Northern Japanese prefecture and he gets up at 4am every day (except Sunday when he looks after his grandchildren). This farmer met the chef at an izakaya (Japanese pub) three years ago and now he is the sole supplier of all of that specific produce to the chef’s restaurant. Which one has more taste? Which excites you more? Although the first has more flavour in the scientific meaning, the second activates more senses thus providing you with a more rounded experience. What then is taste?

Taste is a rich word. Taste can include the surroundings - a definition of taste is how the tongue perceives the food - but perception is led from the brain and so if your brain is in a different knowledge state, your tongue’s perception will be different. As soon as you are more knowledgable about a food - when you have a relationship with it - it will taste different. This is an encouraging thought.

For this first article below, it traces back an incredibly strong food memory and relates it to the present. It also links two totally different cultures through a dish - seemingly on the surface as unrelated to either. We hope to start a conversation, and demonstrate how something is more than the sum of its parts. Memories, relationships, taste.

0 notes

Text

The Egg Sandwich

欧米では、卵サンドイッチは「どうでもいいもの」と見られる傾向があるそうだ。忙しい時や旅に出る時に早く済ませるランチとして、どこでもいつでも食べられるもので、日本のおにぎりのような存在だろう。ニュージーランド出身のスージーは、日本に来てからそういう考え方を変えるようになったという。今回は、スージーが日本で改めて感じだ卵サンドイッチの魅力、そして、その中で味わった子供の頃の思い出を語り、東京のおすすめのお店を紹介する。

Writing & Photo by Susie Krieble

Egg sandwiches are one of those things that for most are a ‘whatever’ food. Usually it’s a no thanks, but if you're on a long drive or you need something quick, then there’s always one around and it’ll suffice. The thoughts that conjure to mind when you think “egg sandwich” are along the lines of mushy, soggy, smelly, old, too-expensive-for-what-it-is, front full/back empty.

That is not the case in Japan.

Here, egg sandwiches are everywhere and they're revered. Bakers and chefs make egg sandwiches with high quality ingredients in high quality establishments. All the components are thought about, kodawari (こだわり). Eggs are not always boiled, they can be steamed, scrambled or made into omelettes.

The bread is light and fluffy and the filling never escapes the comfort of the bread. The filling is spread throughout the sandwich, not just for display purposes on the cut-side. They are fresh, not soggy, yet inexpensive. Some have sweet brown sauce, some have deep fried egg, some are in a burger type bun, some have tartare. Never (usually) lettuce or tomato or unwanted faff. Let’s let the humble egg do the work they say. Simple. Delicious.

The actual egg mixture itself is an interesting one too. To herb or not to herb, to spice or not? In Japan, often you’ll taste mustard and Kewpie (the classic Japanese mayonnaise with the baby logo). In the West we would often see parsley - unfortunately often chewy parsley - maybe dill and probably some chives. Herbs aren’t as liberally used in Japan as the West which asserts the point of the simple sandwich with the egg being the only mentioned ingredient in its title.

In America, the egg sandwich takes on quite a difference appearance. Still tasty, but with many components whereby the egg is simply another ingredient, not a shining star. In Japan, tastes are more refined yet basic, taking care to use fewer but higher quality - arguably - ingredients. American foods have more ka-pow flashbang, and although still can be basic, it is never quite as simple. Not a bad thing.

When I was growing up, dad would make lunch after his bike ride on Sundays. We would often benefit. He started with the carbohydrate base and then built up from there using what he could find in the house. Often cheesy potatoes, vegetables and soba, or egg salad sandwiches (as he called them). We would use multigrain sliced loaf bread (Molenberg, for other Kiwis) and pile in a mixture of hard boiled eggs, Best Foods mayonnaise, herbs from the garden, and salt and pepper. If there was leftover salad we would eat it with a fork from the orange v-shaped plastic IKEA bowl in which the salad was always mixed. I recall making the salad and separately wrapping slices of bread to take to the beach for a personal picnic. Friends would buy lunch but I just wanted an egg salad sandwich.

And now I am in Japan, the land of the egg sandwich, which was quite the surprise. It has been written about a lot, but usually just from the convenience store angle. Who knew this was going to be the thing I ate or craved the most. Being here seems like a natural fit.

Here are some favourites:

スージーからのおすすめ:「東京の卵サンドイッチ」

3206 Bakery Devilled Egg - tartare and soft boiled eggs layered onto soft white homemade bread, ¥440

3206(港区南麻布5-2-39ニュー東和ビル1F)

Seven Eleven's こだわりのたまごサンド Egg Sandwich - the creamiest, best temperature for immediate eating, and most flavoursome of the convenience store offerings, ¥224

セブンイレブン

American タマゴサンド Egg Sandwich - order one ¥500 sandwich and you get two enormous halves. Everyone seems to take away the second. The bread here is a standout and sets other top egg sandwiches apart. It is thick, doughy, and super moist. The filling is a banger too, ¥500 (+ ¥500 drink in the morning), ¥1200 as a lunch set, or ¥500 takeout

アメリカン(中央区銀座4丁目11−7)

New York Witches タマゴカツサンド Egg Katsu Sandwich - opens at 19h until 5h the next day, dreamy combination of lightly crumbed and fried egg omelette with mustard and mayonnaise, ¥850 (for take out)

New York Witches(新宿区歌舞伎町2-38-8 八汐会館3F)

Kissa You, オムレツサンド Omelette Sandwich - a very long queue for the revered オムライス omuraisu (omelette with rice inside) but actually the sandwich is well worth it too. Very creamy, almost scrambled like in texture, ¥900

YOU(中央区銀座4-13-17 高野ビル 1F)

0 notes

Text

Our First Event

Last Saturday, we opened a Bubble Tea Bar for the graduation ceremony at Daizawa International School.

0 notes