Text

A Mathematician’s Self-Referential Take on “The Black Swan” by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Dear World,

You can stop asking me what I think of "The Black Swan." I've written it all down.

Being a former academic mathematician with a background in developing fintech software, I am often asked about my opinion of Nassim Nicholas Taleb's book "The Black Swan." My answer used to be that I hadn't read it, although that wasn't quite true. I had starting reading it but soon found myself bored, switching from reading to scanning and then scanning faster and faster. I didn't want to give an opinion on something to which I hadn't been paying much attention, hence the white lie. And then it got worse. People seemed to think that reading this book would change my life or something. They wouldn't stop pestering me about it, giving me copies of it for birthday gifts, things like that. So I decided I had to come clean. I thought the best way to do that would be to take another look at the "The Black Swan" (referred to as TBS in the sequel) and explain why it bores me. So here goes.

As far as prerequisites are concerned, I will not assume that you have read TBS. For mathematical expertise, it suffices to have a decent idea of what a probability distribution is, what the normal distribution is, and the like. If you have some familiarity with the central limit theorem, that's good, but if not, it's just as well.

You will find that reading this review is a somewhat tedious and laborious affair. I am quite confident that this is not my shortcoming, but a reflection of a certain elusiveness of the book's lines of argument. It is perhaps noteworthy that despite the book's enormous popularity, nobody seems to have attempted a passionless mathematically oriented review.

I. Definition of Black Swan Events

II. The Fluff

III. The Central Distinction: Mild vs. Wild Randomness

IV. The Central Thesis: Blindness to the Black Swan

V. Predicting the Future

VI. The Gaussian Strawman

VII. The Lowdown

I. Definition of Black Swan Events

Paraphrasing and condensing from pages xvii and xviii of the Prologue to TBS, we can say that Nassim Nicholas Taleb (referred to by the initials NNT in the sequel) defines the central term of his book as follows:

Black swan events are events that are rare, have extreme impact, and are retrospectively, but not prospectively predictable.

The third part, retrospective, but not prospective predictability, bears some explanation. The "prospective" part means of course that we didn't and couldn't predict the event before it happened. The "retrospective" part, as defined by NNT, means that

human nature makes us concoct explanations for its occurrence after the fact, making it explainable and predictable.

The use of the word "concoct" indicates that we're kidding ourselves into thinking that the event really was predictable when it wasn't. There is of course an enormous amount of truth in that: hindsight bias, the infamous 20/20 hindsight, has been extensively studied. But it also seems to me that part of our evolutionary process has always been to perform perfectly rational post-mortem analyses of these events, thereby indeed, over time, improving our ability to predict them or lower their impact. I have to admit that not mentioning this at all makes me suspect a case of confirmation bias. But we're still in the prologue, so we'll just put a pin in that for now and continue.

II. The Fluff

TBS is sprinkled with stories from NNT's personal life. My interest in those is zero. That's all I can tell you, except to say that I just did the same thing, telling a personal anecdote, in the opening paragraph above. Therefore, my criticism is self-referential. That's bad, because in a more formal setting, self-referential criticism is valid if and only if it is not valid. But as I said in my personal anecdote (!) above, I never wanted to talk about TBS in the first place…

TBS contains some amount of fiction. Chapter Two in its entirety is fiction, as NNT informs us in a footnote on the first page of Chapter Three. It's not quality fiction in my opinion, and I was bored by it. Other opinions may be possible, but by no stretch of the imagination does the fiction contribute anything to making TBS a recommendable book.

TBS also contains numerous historical and biographical references and anecdotes. This is indicative of a well-read and well-educated author, which is good. For me, however, these references and anecdotes were too scattered and disconnected to be of much value. Different opinions are possible, of course, in this regard. But it seems clear to me that none of this warrants anything close to a must-read recommendation.

A small part of TBS, mostly in Chapter Five, is devoted to explaining and correcting some trivial logical errors that people tend to make, like this one:

[…] if you tell people that the key to success is not always skills, they think that you are telling them that it is never skills, always luck.

That's very commendable, and as a former teacher of mathematics and computer science, I'm all for it. But you wanted my opinion as a mathematician, and the one group that is not in need of these explanations is mathematicians and mathematically inclined people, so I'm still bored. Also, these explanations, while correct and well-written, are not in any way so numerous or extraordinary as to justify a special recommendation for the book.

Some statements and explanations in TBS are such gross simplifications that their informative and illustrative value tends to zero, to the extent that one cannot help but consider them fluff:

The Apple technology is vastly better [than Microsoft], yet the inferior software won the day. How? Luck.

You may argue that referring to the things that I have mentioned so far as fluff is unfair or even inappropriate. Under different circumstances, I would agree. But this critique is written against the backdrop of some acquaintances of mine—and some journalists and pundits as well, for that matter—calling the book a masterpiece, insightful, a must-read for a mathematician like myself, and the like. Measured by those standards, everything I've mentioned thus far is fluff. [1]

As a matter of fairness, I should mention that on page xxvii of the Prologue to TBS, NNT gives a justification for the extensive use of stories and anecdotes in the book:

You need a story to displace a story. Metaphors and stories are far more potent (alas) than ideas; they are also easier to remember and more fun to read. […] Ideas come and go, stories stay.

I like a story as much as the next guy, but I assure you that the above does not apply in the realm of mathematics and statistics. At this point, I am quite comfortable with the prediction that TBS won't be a mathematically relevant book. But then it doesn't have to be. Let us not be deterred from reading on with an open mind.

III. The Central Distinction: Mild vs. Wild Randomness

Chapter Three of TBS sets up what NNT calls the central distinction of TBS, the grouping of all matters that are subject to randomness into two categories, charaterized by mild randomness and wild randomness. The table on p. 36 nicely summarizes the distinction.

Given the fact that TBS is dedicated to Benoît Mandelbrot, and moreover, NNT and Mandelbrot have co-authored an article [2], we may assume that NNT was familiar with Mandelbrot's concept of seven states of randomness. In his early work, Mandelbrot actually started out with the three states mild, slow and wild. He later refined those into seven states, the first of which is mild and the sixth of which is wild. It is clear that NNT's two categories of mild and wild randomness are much inspired by Mandelbrot's three or seven states. There is of course nothing wrong with such an adaptation and simplification. If it serves the purpose of the book, why not. However, I have two comments, one regarding ethical rigor and another regarding mathematical rigor.

Ethical Rigor: In a scientific publication, such an adaptation is permissible only if the original work is discussed and credit is given to its author(s). Failing to do so would not pass scholarly review. NNT does not state that his two categories are an adaptation of Mandelbrot's work. The number of occurrences of the string "seven states" in TBS is zero. Therefore, TBS does not qualify as a scientific publication. Fine, it doesn't have to. So what about failing to give credit in a non-scientific publication? I personally find it unethical. Others may be more lenient, but the minimal verdict that I am willing to accept is "not great." Giving credit would also have been an opportunity to explain Mandelbrot's concept of "states of randomness" to the uninitiated, as it has not received all the attention that it perhaps deserves. An uncredited simplification from three or seven to two states does not do that for me.

Mathematical Rigor: You will have to excuse the laboriousness of the following discussion, but remember, I never wanted to talk about TBS in the first place. I was goaded into it. So here we go.

Needless to say, the author of a book like TBS is under no obligation to adhere to any standards of mathematical rigor. However, if you use a mathematical term to define and argue a thesis, then you must use that term in a mathematically rigorous and meaningful way. More generally, if you use a technical term from a scientific discipline, then you must abide by the prior definition of that term and the standards of that discipline. I posit that this is a prerequisite of meaningful intellectual debate.

In the last line of the table on p. 36, where the concepts of mild and wild randomness are summarized, NNT says the following about mild randomness:

Events are distributed \(^*\) according to the "bell curve" (the GIF) or its variations.

The acronym GIF has been defined earlier in the book as "Great Intellectual Fraud." That's opinion, so we'll ignore it for the discussion at hand. The star refers us to this footnote:

What I call "probability distribution" here is the model used to calculate the odds of different events, how they are distributed. When I say that an event is distributed according to the "bell curve," I mean that the Gaussian bell curve (after C. F. Gauss; more on him later) can help provide probabilities of various occurrences.

Using the term "bell curve" as a synonym for "Gaussian bell curve," and thus for "normal distribution," is in line with common usage. [3] So that part is a valid and helpful clarification. Substituting synonyms, the last sentence of the footnote becomes

When I say that an event is distributed according to the normal distribution, I mean that the normal distribution can help provide probabilities of various occurrences.

First off, it's not events, but random variables that may or not be normally distributed. Ok, we're not pedants, so we'll let that go. But what does it mean that the normal distribution "can help provide probabilities"? If something is normally distributed, then the normal distribution provides the probabilities. Is this being redefined here as something weaker, as in "can help provide, but doesn't really without additional information"? I find myself unable to make sense of this. We'll have to file it under "use of a term (probability distribution in this case) from a scientific discipline (mathematics in this case) that does not meet the standards of that discipline." As a working hypothesis, I will assume that what NNT really means by "being distributed according to the normal distribution" is exactly what everybody else means by it.

Omitting the reference to the footnote and the GIF reference and substituting a synonym, the characterization of mild randomness in terms of distributions now becomes:

Events are distributed according to the normal distribution or its variations.

So what are "the variations of the normal distribution"? I haven't heard the term before. As we all know, the normal distribution has parameters, so strictly speaking, there is no such thing as the normal distribution. It's a family of infinitely many that are all variations of each other in the sense that they are obtained by varying the parameters. But that's not what could possibly be meant here, because it says "the normal distribution or its variations." So the sentence must be referring to distributions that are variations of the normal distribution but not normal themselves. Since I don't know what those are, I did a web search for "variations of the normal distribution." It turns out that one website, the top hit, actually uses "variations of the normal distribution" to mean the different instances of the normal distribution that are obtained by varying the parameters. That's it.

So now what? I could try to make an intelligent guess as to what's meant by "variations of the normal distribution." Exponential families would be a good guess. But nobody calls these "variations of the normal distribution," so we can't really know. [4] We have no choice but to mark this down as the second use of a term (normal distribution in this case) from a scientific discipline (mathematics in this case) that does not meet the standards of that discipline. That's not good, considering that this is happening in what NNT calls "the central distinction" in TBS.

At this point, my boredom has given way to mild annoyance. But we're only on page 36, so let's not jump to conclusions.

IV. The Central Thesis: Blindness to the Black Swan

At the end of Chapter Four on p. 50, NNT lays out the main thesis of TBS: the blindness of humans to the black swan. The thesis is then broken up into five themes, of which I quote the third here, as it is probably the most poignant, and somewhat representative of all of them:

We behave as if the Black Swan does not exist: human nature is not programmed for Black Swans.

The ensuing five chapters then discuss the five themes each in turn. There isn't really anything specifically mathematical in those five chapters, so my opinion as a mathematician—and remember, that's what this critique is all about—is not particularly relevant here. However, I said earlier that I was suspecting a case of confirmation bias in TBS, and this part of the book confirmed my suspicion. NNT gives an eloquent presentation of all the fallacies, biases, logic errors, and other weaknesses that prevent us humans from dealing rationally and efficiently with black swan events and the threats they pose. That's good, as these weaknesses are very real. But what about the other side of the coin? There is ample evidence of humans dealing incrediby well with rare events of extreme impact. If there weren't, we probably wouldn't be here. Actually, perhaps a better way of saying that humans deal well with black swan events is to say that those who don't aren't with us anymore.

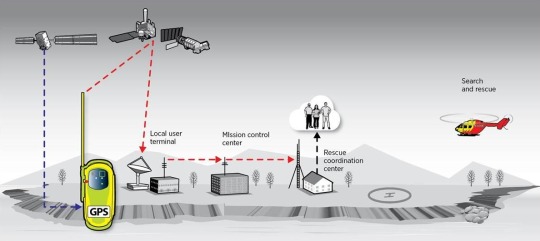

Now that I've said it I suppose I have to give an example of humans dealing well with rare events of extreme impact, although that almost feels silly as there appears to be an infinitude of examples. [5] Take the example of rattlesnake bite in the American outdoors. It's grotesquely rare, but when it happens, it's painful in the extreme and potentially lethal. Clearly, it happens to people as a consequence of some fallacy or other, as in, "Me and my family have been coming here for years, and we've never even seen a rattlesnake! The heck I'm going to watch my step when gathering wood in the underbrush!" But that's the relatively small crowd of Darwin Award winners in waiting. Pick up any book or magazine from the outdoor literature section, go to any park visitor center, talk to the locals, I mean can you even get into the outdoors without being educated on how to minimize the risk of snake bite? And perhaps even more importantly, you can take with you into the outdoors a device that weighs five ounces, fits into the palm of your hand, and has a button which when you push it gets you airlifted to the nearest hospital where they have doctors and nurses and antidotes and painkillers and what not to deal with your mishap. That's how far humanity has come dealing with this particular black swan. That's more than impressive. It's darn near a miracle.

Someone to whom I presented this example argued that snake bite is not really a black swan. It's more like a grey swan since we are aware of its existence and know roughly where and when to expect it. Correct, but what do you want me to do about the truly black swans? Sit around and mull over things which I don't even know what they are, while others are hard at work lowering the risk or impact of snake bites, car wrecks, household accidents, natural disasters, terminal illnesses, you name it? Now there's a way of dealing poorly with rare catastrophic events.

V. Predicting the Future

Part 2 of TBS, consisting of Chapters Ten through Thirteen, pp. 137–211, elaborates on the fact that humans are not good at predicting the future. For example, nobody knew we were going to have the Internet. Ok. [6]

VI. The Gaussian Strawman

At the end of Part 2 of TBS, NNT leads into Part 3 with the words

Some readers may see it as an appendix; others may consider it the heart of the book.

Since some portion of Part 3 is dedicated to the discussion of probability distributions, I will go for the second option and consider it the heart of the book. First off, there is a remark on p. 213, at the very beginning of Part 3, that gave me pause:

[…] for an event to be a Black Swan, it does not just have to be rare, or just wild; it has to be unexpected, has to lie outside our tunnel of possibilities.

Isn't that a modification of the original definition given in the Prologue? Stock market crashes and severe earthquakes, for example, would certainly be black swan events according to the original definition. But they are not outside our tunnel of possibilities: the vast majority of people are lucidly aware of the fact that they do happen. So now I don't really know anymore what a black swan is, and thus, I don't really know anymore what this book is about. I'll just have to let that go for now and concentrate on the upcoming discussion of probability distributions.

Chapter Fifteen in Part 3 is entitled, "The Bell Curve, That Great Intellectual Fraud." As we saw earlier, NNT follows convention by using the term "bell curve" as a synonym for "normal distribution", so what's being said here is that the normal distribution is fraudulent, in a sense that is yet to be determined. The first few pages of Chapter Fifteen are devoted to some numerical examples, and there is no hint of fraud here. Six pages into the chapter, there is a small section entitled "What to Remember," which reads,

Remember this: the Gaussian-bell curve variations face a headwind that makes probabilities drop at a faster and faster rate as you move away from the mean, while "scalables," or Mandelbrotian variations, do not have such a restriction. That's pretty much most of what you need to know.

The statement on probability drop in the normal distribution is correct. I don't see anything fraudulent in that. So if that's "pretty much most of what I need to know," then I don't know what the "Great Intellectual Fraud" in the chapter's title is referring to. There are 18 more pages in this chapter, but I couldn't find an argument that begins with anything resembling "here's why the normal distribution is fraudulent," or ends with anything resembling, "and this is why the normal distribution is a fraud." I could find only two sentences that hint at how and why NNT considers the normal distribution a fraud. The first of these, on p. 236, contains the expression

The traditional Gaussian way of looking at the world […]

This suggests that there is a traditional school of thought whose belief it is that random variables occurring in real life are by default normally distributed. This belief is most certainly false, and thus the normal distribution would in a certain sense be a fraud. The second statement is on p. 252, near the end of the chapter:

One of the problems I face in life is that whenever I tell people that the Gaussian bell curve is not ubiquitous in real life, only in the minds of statisticians, […]

Again, this suggests that statisticians believe that random variables are by default normally distributed, which is false, and hence it is justifiable to call the normal distribution a fraud. Notice that I just did a bit of speculating here, but I couldn't find any other place where the normal distribution is exposed as "fraudulent," so I have no choice but to assume that this is it.

As a mathematician—and one with a decent scholarly record, if you must know—I assure you on the honor of my professional ethics that there is no school of thought among mathematicians or mathematically literate people that is called, calls itself, or could legitimately be called "the Gaussian way of looking at the world." With equal confidence, I assure you that there are no statisticians, mathematicians, or mathematically literate people in whose minds the Gaussian bell curve is ubiquitous, i.e., who believe that random variables should be assumed to be normally distributed by default. NNT's argument is an instance of the strawman fallacy.

To understand this a little better, it helps to do a Web search for "normal distribution ubiquitous." You'll see that indeed, the normal distribution is often called "ubiquitous in statistics," or "ubiquitous in statistical analysis." That's because—and I'm saying this for the mathematical layperson—the normal distribution pops up in a lot of places in the theory of probability where one would not expect it. The mathematically literate reader of course knows that what we're talking about is, first and foremost, the central limit theorem, and also some lesser results like the one that says that under certain circumstances, the binomial distribution can be approximated by a normal distribution with a continuity correction. Personally, I would not describe this situation by saying that the normal distribution is "ubiquitous in statistics," but then I wouldn't argue with people who do. The bottom line is, what NNT does is to misrepresent this collection of mathematical theorems as a "Gaussian way of looking at the world," a position that is then easily exposed as false or, if you wish, "fraudulent." And that's the definition of the strawman fallacy: misrepresenting someone's position so it can be refuted.

VII. The Lowdown

To emphasize again, I never wanted to voice an opinion about TBS. But some of my acquaintances insisted, so here it is: I don't think TBS is an interesting book. Too much fluff, not enough semantic precision, and too much confirmation bias. From a mathematician's point of view, it's actually a bad book, because the attack that it launches on Carl Friedrich Gauss and the distribution named after him falls flat on account of the strawman fallacy.

Nothing that I saw in TBS went into my treasure trove of quotes. My biggest frustration was, "What, you're writing a book about randomness, chance, luck, the unexpected, the futility of predicting and planning, you're telling us that you're proud of your Lebanese Christian heritage, and you never once mention Ecclesiastes 9:11? Oh come on."

Sincerely Yours,

The Fool on the Hill

Notes

[1] Given the book's remarkable popularity, perhaps someone can find the time, or find someone to pay him or her for the time, to copy and paste all the fluff from TBS into a separate document and then count words. I'd be interested to see what the percentage of fluff is.

[2] Mandelbrot, Benoît; Taleb, Nassim. "A focus on the exceptions that prove the rule". Financial Times, 23 March 2006.

[3] Strictly speaking, the bell curve is of course the graph of the normal distribution. But this degree of semantic precision is not very helpful, not even in mathematics.

[4] Much later in the book, on p. 239 and again on p. 275, NNT uses the term "Gaussian family of distributions," and he mentions that the Poisson distribution belongs to that family. That leads me to believe that indeed, what he means is exponential families. But "Gaussian family of distributions" is not a term for which mathematicians have a definition, and NNT never once says "exponential families." Therefore, we cannot know what he means.

[5] Come to think of it, I wonder if there is a book that looks at the history and evolution of the human race as the process of improving our skill of preparing for, avoiding, and dealing with rare catastrophic events. I bet it would be interesting, although probably not nearly as much fun as reading about the fallacies, biases, and logic errors that TBS is all about. TBS vs. that other book may end up being like Jackass vs. a video on pivot tables in MS Excel.

[6] A lot of things that NNT says in this part of TBS sound an awful lot like he's mocking people who make plans, implying they are so foolish as to think they can predict the future. Here's a prediction. I predict that in some distant future we'll be able to make computer simulations of alternate universes with properties of our choice. I would then make one that's just like ours, except that humans don't make plans, knowing that that's futile because of their inability to predict. That'll be fun to watch. Of course NNT is completely missing the point here. The stunning success of human civilization has something to do with the fact that humans have become good at planning in the face of uncertainty.

0 notes

Text

Satellites and Potsherds

Dear Luddites,

It's been nice knowing you. I am no longer one of you. Take care.

I used to think that using any means of orientation more advanced than a topo map and a compass in the backcountry was cheating. It felt like the equivalent of having a helicopter lowering you down onto the summit of Mount Everest. Who would do such a thing. Recently, however, I have found out that the use of Google Earth is a fun way to locate and get to rather fascinating remote places. I mean I could do it without Google Earth (although, to be honest, time is an issue when you get to my age). It's just a ton of fun playing with Google Earth before you go, and to look at large Google Earth printouts rather than topo maps when you're out there. Most of all, however, it's hard for a geek to resist the temptation of using all that insanely advanced technology, built on eons of scientific research and engineering ingenuity, for no other purpose than to sit on a rock in some godforsaken corner of the wilderness and breathe deeply.

More specifically, Google Earth is a great way to find possible sources of water in the desert: just look for light green patches. [1] And then I noticed that when there is a flat bald spot in the vicinity of a green patch, then it's likely that that is the location of a Native American village site or camp site. [2] Here's an example of such a combination:

Here's what the flat spot looked like when I got there:

The moment I saw this I knew that there was no way these guys would not at least have had a camp here, to spend nights when they were out hunting and gathering. Pretty much the only way to confirm such a conjecture is to find potsherds. There wasn't exactly an abundance of them. Running around with my eyes fixed to the ground for what seemed like an eternity netted a total of four, one of which I took a picture of:

Later I made a facebook post of this so that all of my eleven friends could see it. So ultimately, I used Google Earth, a digital camera, and facebook to get a picture of a 1'' x 1'' potsherd in a remote corner of the American desert Southwest in front of eleven people. If you wanted to describe the technology that was involved here in any detail, from the satellites and aircraft that provide the raw images for Google Earth down to my friends' browsers pointed at facebook, where would you even begin? I humbly submit that this an achievement well worth of winning the Hofstadter-Wolowitz Technology Overshoot of the Year Award (TOY Award).

Sincerely Yours,

The Fool on the Hill

Notes

[1] Need I point out that it would be colossally stupid to ever rely on finding water where Google Earth shows a light green spot? If that's what you're about to do, I have a better solution for you: step in front of a bus.

[2] Talking about Native American sites on the Web is a sensitive issue. Protecting these sites from casual damage and illegal looting is, ultimately, impossible. Directing more people to them is very likely to make things worse. On the other hand, talking about them in a sensitive way, without divulging directions or locations, could help raise awareness and thereby lead to better protection.

0 notes

Text

The Internet, Like Everything Else, Is About Choice

Dear Internet Critics,

Please remember that like everything else, the Internet is about choice. The recent Senate hearings regarding the role of the Internet in the alleged Russian attempts to influence the 2016 presidential elections have sparked another round of discussions about the perils of the Internet, not just its role in politics, but also the way it destroys our civility, and the like. Now one of the perils of the Internet is that it tempts us to comment extensively on things that we haven't really thought about enough and don't know enough about. I will resist that temptation and not embark on a lecture on how to fix the Internet. But I will mention one aspect of all this which, as I hope to demonstrate below, I am competent to talk about: let us not forget that the Internet, like most everything else in our lives, is subject to choice. While we cannot control what others put out there, we can control what we read, what we react to and how, and what we put out there. I am not saying that this is the solution to all the (very real) problems with the Internet, but it might just be more powerful than it appears. As the late Robert M. Pirsig once so aptly put it:

The place to improve the world is first in one’s own heart and head and hands, and then work outward from there.

~Robert M. Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Cahuilla Indian Country in the Western Colorado Desert of Southern California

I cannot think of a better way to reinforce my point than to share with you a little anecdote, a vignette really, of what I think was a judicious use of the Internet on my part. The story may not amount to much, but I feel that the sum total of experiences of this nature has elevated my life in ways unimagineable just a few decades ago.

My story takes place in the desert of the American Southwest, more precisely, in the ancestral lands of the Cahuilla Indians in Southern California. The Cahuillas are somewhat different from many other Native Americans insofar as they had little contact with the Spanish, and they did not encounter Anglo-Americans until the 1840s. Therefore, the mid-1800s found them living an unaltered traditional lifestyle as hunters and gatherers. The subsequent history of their territory is an odd one: the northern part has turned into the (sub)urban behemoth of Palm Springs and Palm Desert, and the date farms of Indio and Coachella. The southern part, on the other hand, contains some of the remotest and least travelled backcountry in the American West. It is here that one can find remnants of Cahuilla Indian villages, camps, and scattered homesites. The Cahuillas did not build cliff dwellings, so there is nothing nearly as spectacular as, say, Mesa Verde, or the cliff dwellings of Utah's red rock country. In fact, the traces of Cahuilla habitation are so faint that a person with an untrained eye can walk right through a village site and not even notice it.

In the spring of 2017, I went on a backpacking trip in Cahuilla Indian country whose purpose was to climb an unnamed mountain and to find a Cahuilla camp that is mentioned in a ranger's notes from the 1950s. I made the mountain (the photograph above shows the view from the top), and by some combination of clever scouting and incredibly dumb luck I found the camp in the vast open space seen in the photograph. I have spent enough time in the desert to recognize the collection of flat sleeping spaces that have been cleared of rocks. But that's not really evidence until one also finds the potsherds that invariably adorn the locations of camps and villages, at least those that are remote enough to see almost no visitors. [1]

Potsherd in Cahuilla Indian Camp

Yours Truly's Camp above Cahuilla Indian Camp

Before I can get to my point, I have to also tell you that on the evening before embarking on this trip, I had a casual conversation at a coffeehouse with a fellow who, upon hearing about my plans, endeared himself to me by not warning me of the rattlesnakes, like almost everybody else always does. Instead, he told me to beware of the ghosts of the Cahuillas shooting arrows at me, and he even did the whooshing sound of a flying arrow. What a nice way to be sent on my way.

Imagine my surprise when, on the second evening of my trip, after coming down from the mountain, I was standing on a rock above the Cahuilla camp, looking at the sunset, and all of a sudden there was the whooshing sound of an arrow flying by me. And another. And another, and another, and another. These were not vague or distant sounds, sounds that needed interpretation. This was the loud and clear sound of something arrow-like flying right by me. I know, because believe me, when you're out there in that forbidding, trailless desert, your senses work perfectly well. If they didn't, you probably wouldn't be alive. And the weirdest thing was, I couldn't see anything. It didn't seem possible that something big enough to make that sound could go by me so fast that I wouldn't catch as much as a glimpse of it.

I was torn between enjoying the thrill of ghosts of Native Americans shooting invisible arrows at me and worrying because I was alone out in the desert, where survival is a major concern, and something was happening for which I didn't have an explanation. I ended up settling for the lame and not very plausible explanation that it was a fast-flying insect, like a locust, that could do that. Good enough for the moment.

After a good night's sleep under the stars, a hot day's hike out, and a bone-shaking drive back to the paved road I lost no time finding Internet access to research the matter. Now how do you go about that? I entered something absurdly vague like, "whooshing sound in the desert at dusk" in the search box, and within minutes, I had my answer: it's hummingbirds that do that. Male hummingbirds have a dive-bombing flight maneuver where they come down from 150 feet or more at up to 60 mph, only to abruptly turn horizontal or back up. They use that maneuver to impress females during courtship, to intimidate intruders, or, ostensibly, just for the heck of it.

A Male Anna's Hummingbird Doing a Display Dive, Captured from High-Speed Video

Relative to body length, that speed makes the humble hummingbird the fastest animal on earth, and it outspeeds the spaceshuttle as well as a fighter jet.

Speed Comparison Relative to Body Length

I had seen hummingbirds in camp earlier, one of them hovering directly in front of the bright orange Gatorade jar that you can see in the photograph of my camp above, apparently attracted by the bright orange color. So despite the fact that I don't have conclusive proof, this is a plausible explanation: one or more hummingbirds were dive-bombing at me from above, turning forward directly above my head, without ever coming into my sight. They may have been trying to scare me out of their territory, or perhaps my lanky figure standing on a rock decked out in Under Armour colors was arousing their curiosity just like the Gatorade jar had earlier. [2]

You may wonder why I never looked up to where the sound was coming from. I have asked myself that question, and I have gone on the Internet to learn more about sound localization. It looks like sound localization in the vertical plane is not very well understood. I have noticed since that when music comes out of speakers in the ceiling, I often have trouble locating it, and it doesn't really seem to be coming from above. I guess I need this whole ghost arrow thing to happen again some time so I can catch one of these little critters in the act.

The bottom line is, what I'm trying to say is, this kind of thing is what I use the Internet for, and I'm having a blast. What I do is much the same as before, like going to absurdly remote places in desert. But having access to all this information feels like a veil has been lifted from the world. Everything seems more focused, more brightly colored, illuminated. People talking trash on social media is pretty much off my radar. I know that there are problems with that, and ignoring them doesn't solve them. But a lot of talk doesn't solve anything either. Let us make good choices and encourage others to do so as well.

Sincerely Yours,

The Fool on the Hill

Notes

[1] Since this was a camp and not a village, there are no morteros (grinding holes in the rock) that could be used as evidence.

[2] Or else, they were saying to each other, "Hey, look at the a**hole standing on the rock rubbernecking at the sunset. Let's play the ghost-of-the-Cahuillas-shooting-arrows thing on him. That'll be fun."

0 notes

Text

The “Quarter under the Streetlamp” Fallacy

Dear World,

Please beware of the quarter-under-the-streetlamp fallacy. There is an old joke that goes like this. A man walks down the street at night and sees another man looking around on the ground under a streetlight. So the passer-by says to the guy, "Did you lose something?" "Yeah, I dropped a quarter, can't seem to find it." "Let me help you," says the passer-by. After they've looked around for a while, the passer-by says, "Are you sure you dropped it here?" "Oh no," says the guy, "I dropped it over there on the other side of the street." "Then why are you looking here?" "Well, duh, can't you see there's no light over there? I'd never find it in that darkness!"

This may not be the funniest joke you've ever heard, but of course its point is to illustrate a fallacy. Whenever we're working towards a goal—be it as individuals, as a team, as a society, or even as all of humanity—there is a temptation to pick the strategy that is most easily implemented, and for measuring our progress, the metric that is most easily tracked. The elation that we feel when we have found a strategy that we know how to implement can mask the fact that it is not a good strategy for the purpose at hand. The relief that we feel when we have found a metric that is easily evaluated can prevent us from seeing that we're not measuring our progress at all.

Needless to say, being aware of the quarter-under-the-streetlamp fallacy doesn't make it any easier to come up with good strategies and metrics. On the contrary, it tends to make it harder because it forces us to confront the true difficulty of the problem. But we may just be rewarded with better results.

In order to remain mindful of the fallacy, I have set a little alarm in my mind that goes off whenever we use a strategy that everybody knows how to implement, or when we use a metric that is ridiculously easy to track. Did we perhaps choose this strategy or metric because it saved us from having to do hard work and hard thinking? The answer may be no, but it is worth checking.

Let me give you an example from the world of information technology, of which I am more or less a part. Using the term "everybody" as a synonym for "everybody except perhaps a few on the fringes of society," I believe it is fair to say that everybody considers it a worthy and important goal to grant equal opportunity to the genders in the world of IT. Moreover, there is an overwhelming consensus that this goal has not yet been reached. So we're working towards it, and of course we want a metric to measure our progress. Many believe that the appropriate metric is to look at the percentage of each gender employed in IT (perhaps broken down by segments), and consider the goal of equal opportunity achieved if these percentages equal the corresponding percentages in the population at large. There are also those who consider this metric to be flawed. This is not the place to go into that controversy. All I want to point out is that this is a typical example of a metric that sets off my little alarm: it is a measurement that is very easy to take. Therefore, when we use this metric or advocate its use, we should perhaps pause for a moment and ask ourselves, "To what extent was our choice influenced by the fact that it was the easiest one?" [1] Perhaps all's well and good, and no mistake was made. All I'm saying is let's make sure we're not looking for the quarter under the streetlamp.

Sincerely Yours,

The Fool on the Hill

Notes

[1] Finding that a metric is flawed does not necessarily mean that it should not be used at all. A flawed metric may well be better than none at all. But in that case, it is important to be aware of the flaws.

0 notes

Text

Kirkman’s Law and You

Dear Humanity,

Don't despair. Here's why. I just got back from my annual spring pilgrimage to the arid lands of Southern California, where I divide my time between desert solitude and hanging out in social spaces like coffee houses, public libraries and such, places that are conducive to coding, guitar playing, and conversing with strangers.

Cahuilla Indian Country in the Western Colorado Desert of Southern California

This year, for the first time, I was dreading the social part of the trip. How was I going to deal with the inevitable onslaught of noisy, dissonant antagonism, of sinnloses, nervtötendes Gezeter, as the Germans so aptly put it, that seems to have usurped our political discourse? Escapism, perhaps, as in, "Oh, enough of politics already, let's talk about collecting stamps"? No thank you. Or the conciliatory approach, as in, "Come on people now, let's all listen to each other and meet in the middle"? Yeah, right, meeting halfway between reason and absurdity, that has got to be the solution.

To my stunning surprise, my fear turned out to be unfounded. I kept bumping into people left, right and center who were eager to talk and to listen. They were well-informed. They spoke thoughtfully, with originality, understanding and insight. Perhaps most impressively and surprisingly, they kept asking me, with genuine interest, what I thought and what my experience had taught me on whatever subject we were talking about.

I won't try and summarize any of my conversations here. That's not the point. The point is that it was a form of discourse and communication that was entirely different from what I have come to expect. I can't say that I fully understand what is afoot here. But I think I do understand it all from a 30,000' point of view.

As is often the case, to understand we must first remind ourselves of Kirkman's Law.

Kirkman's Law: Every organization, movement, or system designed and run by humans will eventually be taken over by assholes.

That is perfectly normal. What is perhaps not normal is that we live in a day and age where there seems to be an odd convergence, like a cluster, of this phenomenon. An unusually large number of organizations, movements, and systems, representing a wide spectrum of belief systems, are experiencing accelerated assholization at the same time. Examples are capitalism, the country of Venezuela, the conservative right, and the liberal/progressive left.

The good news is that this is no reason to despair. It is no reason to despair because assholism, although apparently uneradicable, is also unsustainable. There is overwhelming historical evidence that the old, assholized organizations, movements, and systems always fall by the wayside, and entirely new, better ones emerge in their stead. [1] That's called human progress, and it has always worked that way. Here are some examples: everything. Name one reason why that should end tomorrow. So don't despair. Everything will be all right. Every little thing is going to be all right.

And if you will allow me just one bit of preachiness, I'll leave you with this quote by the late Robert M. Pirsig: “The place to improve the world is first in one's own heart and head and hands, and then work outward from there.”

Sincerely Yours,

The Fool on the Hill

Notes

[1] One could say that this is the purpose of assholes in the grand scheme of things: by taking over everything they make the status quo so unbearable that the rest of us start looking for entirely new ways, which, being creatures of complacency, we might not have otherwise done.

0 notes

Text

Dear C++,

I love you. Please don't make me hate you. In a recent blog post, Herb Sutter said about the upcoming C++17 standard revision, "C++17 will pervasively change the way we write C++ code, just as C++11 did." [1] There have been a number of similiar comments from high-profile members of the C++ community in recent years. For example, Bjarne Stroustrup has, on several occasions, stated that "C++11 feels like a new language." [2] When people like Stroustrup and Sutter say things like that, there must be something to it. My gripe is not that it is so. My gripe is that it is being said as if it were something to be proud of, or at least not to be concerned about.

C++ is a tool. Making changes to a tool that are severe enough to "pervasively" change the way the tool is used is per se and by default a bad thing. It diverts people's attention from the very thing that is the tool's reason d'être, namely, to get some good work done. That's bad. At best, it leads to a loss of productivity and quality; at worst, it gets people hurt.

Now don't get me wrong, it is of course entirely possible that a radical change to a tool brings so many advantages in the long run that it is worth going through a phase of lesser productivity and increased risk. The point is that if you make such a change, you better be darn sure that you're looking at a good trade-off. This is not the place to investigate if the changes to C++ that came with the recent standard revisions represent a good trade-off or not. What concerns me is the casualness, even pride, with which we are presented with the fact that we are given a "new language." In other words, it is not my job to figure out if this "new language" thing is a good trade-off. It is the job of the people who made these changes to be concerned about that trade-off, and if they decide it's a good one, to explain their decision.

Needless to say, a decision on a trade-off is by its very nature a matter of discretion. If it were not contentious, it could hardly be called a trade-off. The problem is that the people who are responsible for C++ don't seem to see that there is a trade-off at all. Imagine a young person learning C++, starting her first job, and studying existing code, only to find that she's looking at a "new language" for every 3 year period (the proposed time span between C++ standard revisions) during which the code was written. Imagine you are the leader of a C++ project with a sizeable team and a non-trivial time horizon, struggling with all the problems that come with such an endeavor, coming into work after yet another night with no sleep, only to be hit with a "new language." In my book, these are serious issues. I would think very carefully before using a tool whose creators appear to be insensitive to such concerns.

To say it again, dear C++, lest you forget: I love you. My respect for the achievement that the C++ language represents and my admiration for the intellectual capabilities of its creators know no bounds. I really mean that from the bottom of my heart. But you know what? I have a life, and a big part of that life is to get work done. I am not going to ask you, "What have you done for me lately," because I know you have been working very hard doing things for me. You have the best intentions. But remember what Linus van Pelt of the Peanuts once said, "A lot of harm in this world was done by people who had the best intentions." So I'm asking you to stop and think if what you're doing is really all that great for me. I've been having doubts about that lately.

Sincerely Yours,

The Fool on the Hill

Notes

[1] https://herbsutter.com/2016/06/30/trip-report-summer-iso-c-standards-meeting-oulu

[2] https://isocpp.org/tour

http://www.stroustrup.com/C++11FAQ.html

0 notes

Text

Dear Internet,

It pains me to say this, but quite frankly, right now, I'm disappointed in you. Is it asking to much that around the time of a celestial event like the recent conjunction of Jupiter and Venus, a search for "Jupiter Venus conjunction" should yield, among the first few results, a link to a concise and comprehensive explanation of why Jupiter and Venus appeared the way the did in the sky? Perhaps I'm missing something, but I didn't see that.

So let's you and I see what we can find out about this without spending the whole day. Then perhaps someone who knows what she's talking about will write that concise and complete explanation.

Orbital inclination

Many people, including myself until recently, believe that all planets in our solar system travel around the sun in the same orbital plane. If that were true, then, during a conjunction of two planets, there would be a brief moment where the two planets would appear on top of each other. For example, during the June 30, 2015 conjunction of Jupiter and Venus, Jupiter would have been hidden behind Venus. But that's not what happened. Jupiter and Venus came very close to each other, but they were never in the same line of sight. The angle by which they missed each other was about 1/3 of a degree. That's actually small as conjunctions go. When Saturn and Mars passed each other last year, there was a huge vertical gap between them.

So what gives? The answer is: orbital inclination. There is a non-zero angle between the orbital planes of any two planets. To your credit, dear Internet, the Wikipedia page on the subject explains that really well, and it even has a table that lists the angles of the orbital planes of all planets relative to the ecliptic, that is, to Earth's orbital plane. The orbital inclinations of Jupiter and Venus clock in at 1.31 and 3.39 degrees, respectively.

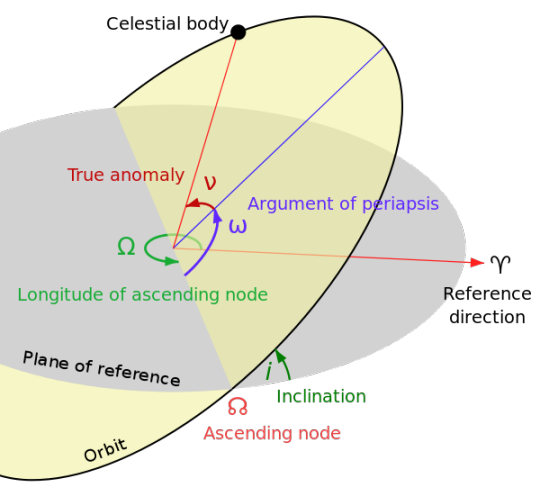

Longitude of the ascending node

Given the information we have so far, it could be possible for Jupiter and Venus to be as much as 1.31 + 3.39 = 4.7 degrees apart during a conjunction. But knowing the orbital inclinations is of course not enough to understand how the planets can appear relative to each other in the night sky. We also have to know how the axes of intersection between the planets' orbital planes and the ecliptic (Earth's orbital plane) are oriented. Are they all the same? No, they're not. The orientation of these axes is measured as "longitude of the ascending node," which I think is a cool term because it is pretty much self-explanatory. [1]

Now to be honest, dear Internet, here's where I'm beginning to get annoyed with you. First off, the Wikipedia article on the subject has one of those "This article sucks" warnings at the top. Secondly, when I try to get a list of the longitudes of the ascending nodes of all planets, by searching for "list of the longitudes of the ascending nodes," the top results are a bunch of slow-loading crap that does not have such a list. I have to collect them by searching for "<name of planet> longitude of the ascending node." And then, the first link that actually has that value is like the fifth one in the list of results (or was last time I looked). [2].

Anyway, just for completeness sake, for Jupiter and Venus, the longitude of the ascending node is 100.55615 and 76.68069 degrees, respectively. This is according to NASA fact sheets. Other web pages, dear Internet, list slightly different values.

Putting it all together

Knowing about orbital inclination and longitude of the ascending node should be enough to understand why planets appear the way they do during conjunctions. Given any two planets and the longitude of a conjunction between them, it should be a matter of pretty basic trigonometry to find out how they appear in the sky. I think. If I had a lot of free time on my hands, I would set out to do it, and I'm sure I would run into a million unanticipated issues. That's why I want the answer from you, dear Internet. That's what you're here for.

By the way, since I did not do any of the calculations to explain the 1/3 degree between Jupiter and Venus during their recent conjunction, I did not even try to find out what the exact longitude of that conjunction was. I shudder to think what kind of a drag it would be to find that on you, dear Internet.

So please, dear Internet, see to it that someone who knows what she's talking about writes all this up, nicely presented, easy to find, perhaps with an interactive model to play with? That would be so cool. And while you're at it, could you please answer this question for me: if the lifetime of our solar system were infinite, would there be a conjunction of any two planets at every longitude, in an appropriate sense of "every"? What about more than two planets? If not, what are the restrictions? Somebody must know this. It is your job, dear Internet, to transmit that knowledge to me, because I want to know.

Sincerely Yours,

The Fool on the Hill

Notes

[1] Of course you have to know what the origin and the direction of that longitude are, but that's easy to find out: it starts at the first point of Aries and proceeds counterclockwise when viewed from the north.

[2] One could of course argue that I should add such a list to the Wikipedia page. I could. But then I am very far from being an expert in astronomy. Should I really touch that page? I think not.

0 notes

Text

Dear Indiana, Dear Liberals,

Please stop making me feel so gosh darn lonesome. First off, to be absolutely clear about this, sorry, Indiana, but what you’re doing is wrong. And I don’t mean wrong in the sense of, “I happen to disagree with you, but carry on.” No, it’s wrong in the sense of, “You can’t do this.” I mean, I see where you’re coming from. Wanting to maximize people’s freedom is a good thing. But there are some choices that conflict with other, more important values. Like, when a white person walks into a bar and the bartender says, “Sorry, we don’t serve whites here,” then we can’t allow that. The bartender just doesn’t have that freedom of choice. Not here, not in our society. To be honest, I don’t even want to discuss that. So, the bottom line is, if I were in a room full of you right now, I would feel terribly lonesome.

And that takes me to you, dear liberals. When I’m in a room full of you, I’m much better at pretending that I’m not feeling lonesome, but I am. Almost everything I see in my fb stream—or in any other liberally biased news source on the Internet, for that matter—is things like a photograph of a road sign saying “Welcome to Indiana” with a second, similar one saying “Turn your clocks back 200 years” photoshopped below it, or Andy Borowitz calling Indiana stupid and considering that to be funny. [1] So, ok, I think I know what you’re getting at. You’re saying, let’s not grace Indiana’s action with a rational argument, because that would imply they have a defensible point, and we don’t think they do. Ok, fine, I get that. I actually do have some questions in this regard, but let’s say they’re not that important. What you’re doing here is perfectly legitimate. After all, this country is very much based on the notion that there are things that are not subject to intellectual debate, because they are self-evident. (I think it’s in the second paragraph, and the title says that it was unanimous.)

And yet, dear liberals, I’m feeling lonesome in that roomful of you. It took me a while to figure out why. Let’s take another look at the people who lead the fight against things like colonialism, racism, segregation, apartheid, and the like. (You know who they were. I get this thing sometimes where I don’t even feel worthy of saying their names.) Just like you are doing now with Indiana, they never once let themselves be drawn into an intellectual debate on the virtue of their goals. That was self-evident, and they refused to discuss that. But there was something else that they refused to do. They refused to meet their adversaries with arrogance, condescension, silliness, let alone hatefulness. No matter how hard the other side tried to pull them down to that level, they didn’t do it. That’s because they knew that what you’re fighting with is what you’re fighting for. People say that stupid is as stupid does, but that’s true for a lot more things than stupidity. You’re fighting with arrogance, condescension, and silliness, you’re fighting for arrogance, condescension, and silliness. I think it was an opossum that once said, “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”

Now don’t get me wrong, I’m not trying to be holier than thou here. I treat people with arrogance, condescension, silliness, even hatefulness all the time. But that’s because I’m an asshole, and it’s not ok. If you want me to join your fight or cause or campaign, you have to first convince me that you can be less of an asshole than I am. Then we can talk.

So, dear Indiana and liberals,

Here’s some advice for you. As for you, Indiana, if you can’t see the error of your way right now, consider this: your thing is not going to last anyway. Some court is going to shoot it down sooner or later. In the meantime, it’s just going to bite you in the ass. So what’s the point? And to you, dear liberals: fighting the good fight and trying to make the world a better place is cool. I’m for it. But remember that whatever your cause is, Step 1 is always the same: DBAA, don’t be an asshole.

Sincerely Yours,

The Fool on the Hill

Notes

[1] Actually, I rememeber one share in my fb stream where a christian church—possibly the Unitarians, I don’t remember—said that they were opposed to the Indiana law because the christian religion is not a hateful one. At first, I liked that. But then it occurred to me that this is not the point. Even a hateful religion—and as far as I am concerned, you’re perfectly free to join one—does not entitle you to the kind of discrimination that Indiana condones. Hate whoever you want, but you can’t discriminate.

0 notes

Text

Dear Eurozone Members Other Than Greece,

Please shit or get off the pot. Give Greece the money it needs to stay afloat, or let it leave the eurozone. You keep telling the Greeks that they can borrow more money if, within a few days, they come up with a verifiable plan on how to change habits and administrative structures that are rooted in centuries of history. Moreover, you expect the resulting improvements to be timely and efficient enough to enable Greece to repay all that borrowed money. That’s absurd. Right now, you have two choices:

Keep Greece in the eurozone by granting it financial assistance for the foreseeable future, pretty much unconditionally, the way you would subsidize a remote, economically disadvantaged region of your country.

Let Greece leave the eurozone.

Making the necessary changes in Greece so it can be a functioning member of a European monetary union is important, but that’s independent of the decision whether or not to keep it in the eurozone for now.

The problem of North vs. South in Europe

Suppose you’re living in the Netherlands, before the introduction of the Euro. Someone offers you to increase your retirement nest egg by 10%, under condition that you exchange it into Italian Lire, or Spanish Pesetas, or Greek Drachmas, and leave it there until you’re ready to spend it during retirement. Would you do that? Of course not. And there you have it, the essence of the problems that plague the Euro: you would never have dreamed of moving your nest egg from Dutch Guilders into Lire, Pesetas, or Drachmas, not even at a premium, and then, literally overnight, Guilder, Lira, Peseta, and Drachma are all the same. That can’t be right.

It’s been said many times before, but let’s say it again: the main difference between the pre-Euro era and the present is that before the Euro, the Southern European countries could and did use the value of their currencies to make their products more competitive elsewhere in the world. By devaluing one’s currency, one makes one’s own products cheaper abroad. That’s the primary reason why a Dutch person would not want to change her nest egg into a Southern European currency. Someone who holds Lire, Pesetas, or Drachmas, but plans to spend her money on Dutch goods in Guilders, can expect to be losing money over time. [1]

The introduction of the Euro made it impossible for the members of the Euro zone to set their own monetary policies. In particular, each of them now has a fixed exchange rate with all other members of the Euro zone, and the exchange rate with other currencies such as the US dollar is the same for all members of the Euro zone. Moreover, during the first 15 years of the Euro, the European Central Bank has pursued policies resembling those of pre-Euro Northern European countries such as Germany. The net effect of all this is that those countries of the Euro zone that used to have soft currencies now find themselves forced into using a hard currency. [2] It is probably safe to say that this is the main reason for the massive recession that these countries are experiencing, with unemployment rates rivaling those of the Great Depression in the US.

Over the last few years, the European Commission (EC), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the European Central Bank (ECB) have carried out a concerted action to resolve this situation by offering bailout money to the affected countries in return for all sorts of changes that are aimed at making their economies more competitive, thereby enabling them to be stable members of a hard-currency monetary union. This concerted action has shown results, but it has not yet been successfully completed. Whether successful completion is likely is a matter of fierce debate, with the far ends of the political spectrum, both left and right, being the most skeptical. However, there is one country where this carrot-and-stick policy has led to a dramatic situation: as of this writing, Greece is days away from government bankruptcy.

The special problems with Greece

The apparent difference between Greece and other Southern European countries is that the problems that prevent Greece from functioning with a hard currency are more serious and more deeply rooted. Perhaps the main reason why this is not very widely known or taken into account is that it is difficult to say it without sounding like a bigot. The fact that, simplifying only slightly, Greece is the cradle of the entire culture on which the European Union is based does not make this any easier. But the sad fact is that in Greece today, fraud, corruption and favoritism are rampant, and participation in the tax system is widely considered optional. The sad state of government bureaucracy in Greece is epitomized by the absence of a functional system of land registration. The past 10 years have shown that under such circumstances, entering a monetary union with a hard currency is disastrous.

It appears that the members of the eurozone other than Greece believe that Greece’s problems can be rectified in the short term, and that as a result, Greece will be able to repay the money that it needs to stay in the eurozone. Needless to say, everybody is entitled to their own opinion in this matter. But then, let us face it, Greece’s problems are largely problems of habits, attitude, and traditions. Of course these things can and will change, but not at the stroke of a pen. It would certainly be nice if Europe could demonstrate that such changes can be accomplished with the help and support of other, friendly and allied countries. However, effectively telling Greece, “We’ll lend you the money to avert government default if you change the mentality of your population within the next few days” is not likely to be the way to do it.

So, Dear Members of the Eurozone Other Than Greece,

Please understand that enabling Greece to be a functioning member of the eurozone is a very difficult long-term project. Getting it under way soon and completing it successfully is indeed critical to the success of the European Union as a whole. But that doesn’t mean it must be done quickly, because it can’t. What you need to do is take it seriously and understand the enormous difficulty of the task. As for the time frame, my suggestion for a first guess would be fifty to a hundred years. A good place to start would be to study Greek history and try to understand how today’s problems might be rooted in the way it lived under and liberated itself from Ottoman occupation. And while you’re on that Wikipedia page, you may also want to brush up on your knowledge of ancient Greece. That will remind you of another great reason to be respectful in the way you offer help to the Greeks: all of our lives would be shit without them.

Sincerely Yours,

The Fool on the Hill

Notes

[1] Of course there are other considerations here, such as the amount of interest that you earn on your money. But most people wouldn’t even go there: the Dutch Guilder is a hard currency, and nobody in his right mind would move his nest egg from a hard currency into a soft currency, end of story.

[2] There are some indications that the European Central Bank is now trying to do the opposite, namely, to turn the Euro into a soft currency, thereby forcing member countries that used to have hard currencies into using a soft one. But it is too early to say if this is even going to happen, let alone what the consequences would be.

0 notes