Text

Your observation of the portrayal of Carnival as both a celebration of diversity and a backdrop for social tensions is really interesting, specially when we see it from Eurydice's perspective, like you mentioned, an outsider experiencing Carnival for the first time.

Black Orpheus (1959) by Marcel Camus

The film Black Orpheus (1959) by Marcel Camus is both visually stunning and informative, as it shows the developing country of Brazil through the celebration of Carnival. This event brings emphasis onto the mise-en-scene of the film and is used to create a timeline for the story of Orpheus and Eurydice. We see this theme in the beginning of the film, as the first sequences shows communities preparing for the festival and the introduction of the main characters.

We as the audience experience from the first few minutes of the film the preparations of the festival through Eurydice's perspective, as it is her first time being in Brazil. There is a overwhelming feeling of people coming together and a developing environment that isn't familiar to many during this time. It's a reflection of Brazil's acceptance and celebration of racial democracy, as in the readings of Dos Santos, he states, "Denying carnival as an inherent part of struggle that black people have been involved in to achieve recognition represents the obliteration of the historical memory of black people who see themselves as the authors of goods of those festivities." Although there is celebration amongst the community, it comes with the contrast of different political agendas. We see this through the cinematography of Eurydice's walk in the area, as the overhead shot shows the separation of communities, but also the changing and developing minds of others open to diversity. I believe it's an effective start to a film regarding racial diversity in Brazil and the racial violence that is shown later during the actual festival. Overall, the beginning sequence of the film is to plant narrative, but also the important details that are connected to the celebration of carnival through the use of cinematography, setting, and use of bodies.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yes, I think reframing that scene as a critique rather than comedic relief added depth to the film. It reinforces the film's portrayal of Brazilian identity, balancing celebration with social issues.

Orfeu Negro (1959)

Reflecting on Myrian Sepúlveda dos Santos's analysis, the pawn shop scene in Marcel Camus's "Orfeu Negro" serves as a poignant commentary on Brazil's socio-economic conditions and racial dynamics. Through the mise-en-scène, we observe a bustling environment where the urgency to participate in Carnival underscores deeper issues of poverty and inequality.

The cinematography, focusing on Orfeu's interactions amidst the chaos, subtly critiques the societal neglect of these issues.

Lighting and editing contribute to the scene's hectic atmosphere, while the sound, a mix of dialogue and background noise, emphasizes the communal desire for escapism through Carnival.

This sequence, rather than being a mere comedic relief, underscores the contrast between the vibrant celebration of Carnival and the harsh realities faced by the characters. It invites viewers to reflect on the broader social context, mirroring dos Santos's insights on the film's portrayal of Brazilian identity, where the celebration of Afro-Brazilian culture coexists with the glossing over of systemic challenges. This scene exemplifies how formal cinematic elements can enrich the narrative, offering a deeper understanding of the film's artistic and societal implications.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Does the color palette of the film change throughout? If so, how does it reflect the evolving emotions and societal conflict?

The Chromatic Tapestry of Love and Strife in West Side Story

In the pivotal dance scene of "West Side Story" (1961), where Tony and Maria first connect, the chromatic choices in costume design deepen the emotional and racial complexities of their budding romance. Contrary to the original interpretation, Tony dons a striking yellow jacket, and Maria is adorned in a white dress with a red bow, adding nuanced layers to Lauren Davine's analysis.

Davine's exploration of color as a racial and emotional signifier is particularly intriguing in this context. The yellow jacket worn by Tony might represent optimism and hope. However, within the charged environment of the film, it also hints at the racial tension that surrounds the Jets and Sharks. The use of yellow could suggest the fragility and vulnerability of Tony's position in the face of racial conflict.

Maria's white dress with a red bow becomes a canvas of symbolism. While the white signifies purity and innocence, the red bow introduces an element of passion and, in the context of Davine's analysis, possibly a rebellion against societal norms. The combination of white and red could symbolize the defiance of love against the backdrop of racial prejudice.

Examining the scene through formal analysis, the colors contribute significantly to the mise-en-scène. The yellow jacket and white dress with a red bow stand out vividly against the dark and gritty background, emphasizing the characters' isolation in the midst of the brewing conflict.

The choice of colors is also reflected in the cinematography and lighting. The warm hues surrounding the couple create a visual warmth, enhancing the romantic atmosphere. Simultaneously, it underscores the stark contrast between Tony and Maria's love and the hostility of the world around them.

In conclusion, the chromatic tapestry of Tony's yellow jacket and Maria's white dress with a red bow in the dance scene of "West Side Story" offers a nuanced interpretation of love and racial tension. The cinematic elements work in harmony, contributing to the overall artistic presentation and amplifying the thematic depth of the narrative.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I agree, the red symbolism in WSS is really effective, especially in how it subtly portrays the characters' emotions. Your point about Anita's scarf is really interesting, I hadn't ever noticed before. Thanks for sharing!

Viewing Response 1 (Westside Story--1961)

The color red in 'West Side Story' serves as a subtle yet powerful symbol of the film's underlying racial tensions. This symbolism extends beyond the movie's vivid lighting and is intricately woven into the characters' costumes, adding layers of meaning to the narrative. Anita's costume choice, particularly her black and red scarf used when she goes to find Tony, exemplifies this.

Anita initially wears the black side out while retaining bits of the red side visible, demonstrating a guarded attitude towards Americans after Bernardo's death.

This changes dramatically after the Jets' assault. Once Anita goes through this trauma, she no longer believes that there can be peace between the recent immigrants and the Americans and has the red side of the scarf on full display, completely covering the black side. Here, Anita lies about Maria’s death, hoping to keep her away from the Americans (and Tony) for good.

Ultimately, the color red in 'West Side Story,' as expertly analyzed by Davine, becomes a visual metaphor for the evolving attitudes and emotions of the characters, particularly in the context of racial conflict.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watchmen - Final

Introduction

In both film and race theory, the works of Jacques Lacan, Judith Butler, Audre Lorde, and Stuart Hall are known for their exploration of identity, representation, race, and power dynamics within media narratives. Lacan's exploration of identity formation through the concept of the mirror stage lays a foundational understanding of how individuals develop a sense of self through external images and representations. This notion intersects with Butler's theory of gender performativity, which expands upon Lacan's ideas by highlighting how gender identities are not inherent but are rather performed and constructed through repeated acts within societal norms and expectations. Together, Lacan and Butler challenge essentialist views of identity, emphasizing its fluid and performative nature within social contexts. Building upon this framework, Lorde introduces the concept of intersectionality, which considers how various social categories such as race, gender, class, and sexuality intersect and shape individuals' experiences and identities. Furthermore, Lorde's intersectional perspective delves deeper and furthers the discussions initiated by Lacan and Butler, highlighting the interconnectedness of multiple dimensions of identity and the importance of recognizing the unique experiences of individuals situated at the intersections of different axes of oppression and privilege. Additionally, Hall's critical analysis of racial representation in media further extends this conversation by examining how media narratives construct and perpetuate racial stereotypes and power dynamics. His work emphasizes the need for a vigilant and critical engagement with media representations, urging viewers to deconstruct and interrogate the underlying ideologies and hegemonic structures that shape these representations. By synthesizing these perspectives, we gain a holistic understanding of the complex interplay between identity, representation, and power within media narratives.

Methodology:

In this analysis, I will begin by providing an overview of the key concepts from the works of Lacan, Butler, Lorde, and Hall. I will then explore how these theories intersect and diverge, before delving into their application in analyzing the themes of identity, gender, race, and representation in Watchmen.

Common Themes of Identity and Representation: Lacan, Butler, Lorde, and Hall

A fundamental thread weaving through the works of these theorists is the notion of 'identity.' Lacan, through the 'mirror stage,' posits that encountering our reflection, both literally and metaphorically, is pivotal in the development of our sense of self. He elaborates, stating, 'We have only to understand the mirror stage as an identification, in the full sense that analysis gives to the term: namely, the transformation that takes place in the subject when he assumes an image' [1]. This assertion emphasizes the profound impact of external images and representations on the development of one's sense of self. By framing identity as a process of identification with an external image, Lacan highlights the inherently relational nature of identity construction. This suggests that our understanding of ourselves is deeply intertwined with the images and representations we encounter in our environment, whether they be literal reflections or symbolic representations within media and culture.

Similarly, Judith Butler's exploration of gender performativity builds upon Lacan's theories, emphasizing how societal norms and expectations influence our expressions of identity. She contends, 'Privilege operates in many ways, and two ways in which it operates include naturalizing itself and rendering itself as the original and the norm' [2]. Butler critiques conventional narratives, particularly those surrounding gender and sexuality, for perpetuating hegemonic ideals and norms. She argues that these narratives construct and perpetuate specific gender performances that marginalize and constrain individuals.

One key connection between Lacan and Butler lies in their recognition of the performative nature of identity. Lacan's concept of identification implies an ongoing performance of self in relation to external images, while Butler's notion of gender performativity extends this idea to encompass the ways in which individuals enact and embody gender norms. Both theorists emphasize the role of social constructs and cultural narratives in shaping individuals' identities, highlighting the performative aspect of identity as a continual process of enactment and negotiation within societal frameworks.

However, while Lacan and Butler offer valuable insights into identity, their theories can overlook some aspects and complexities of identity. Audre Lorde's perspective, for example, emphasizes the multidimensionality and intersectionality of identity. She argues that identities are shaped by intersecting factors such as race, class, gender, and sexuality. Media narratives often fail to reflect this complexity, presenting limited portrayals that can alienate viewers from diverse backgrounds. Lorde advocates for an intersectional analysis of media representation, which considers how different identities intersect and interact within cultural narratives. Lorde's assertion that "Certainly there are very real differences between us of race, age, and sex. But it is not those differences between us that are separating us. It is rather our refusal to recognize those differences, and to examine the distortions which result from our misnaming them and their effects upon human behavior and expectation" [3] highlights the importance of acknowledging and examining these intersecting identities within media representation.

Stuart Hall builds on this and adds another layer to the analysis with his work on cultural studies. He argues that audiences are not passive consumers but active participants in making meaning of media. Viewers engage with narratives, interpreting them through their own cultural experiences and social locations. He argues that "popular culture always has its base in the experiences, the pleasures, the memories, the traditions of the people," [4]. This active role allows viewers, particularly those underrepresented in the media, to potentially subvert or challenge the messages encoded within media content. By analyzing how viewers engage with characters and storylines that may not fully reflect their identities, we can delve into how media both reinforces and challenges existing social constructs.

In conclusion, Lacan's theory of the mirror stage and Butler's concept of gender performativity converge in their recognition of the performative aspects of identity construction. Both theories highlight the influential role of external images and societal norms in shaping individuals' self-perceptions. They both emphasize that identity is not something inherent or fixed but rather a dynamic process enacted within cultural contexts. While Lacan focuses on the foundational role of identification with external images in the formation of identity, Butler extends this idea to explore how individuals perform and embody gender within societal expectations. Additionally, Audre Lorde's intersectional perspective adds another layer to this discussion by emphasizing the multidimensionality of identity, showcasing how different aspects such as race, class, gender, and sexuality intersect and shape individuals' experiences. Stuart Hall further complements this analysis by highlighting the active role of audiences in interpreting and negotiating media representations of identity. Thus, these theorists collectively contribute to a comprehensive understanding of identity as a complex interplay between individual subjectivity and broader cultural and societal influences. Although Lacan, Butler, Lorde, and Hall approach the issue of identity from distinct angles, they share a fundamental concern with the power of media and our surroundings in shaping our sense of self.

Diverse Approaches to Identity in Media: Lacan, Butler, Lorde, and Hall Compared

While Jacques Lacan, Judith Butler, Audre Lorde, and Stuart Hall share common interests in analyzing identity, representation, and power within media narratives, each offers a distinct lens through which to view these phenomena. Lacan's psychoanalytic framework delves into the internal processes of identity formation, emphasizing the role of the unconscious and the mirror stage in shaping individual subjectivity. As he explains, “the I is precipitated in a primordial form, before it is objectified in the dialectic of identification with the other, and before language restores to it, in the universal, its function as subject,” [5]. This emphasis on the early stages of identity formation underscores Lacan's interest in the unconscious and the ways in which individuals come to understand themselves within the context of societal norms and expectations. By examining the mirror stage as a pivotal moment in the development of identity, Lacan provides a foundational understanding of how individuals navigate their sense of self within cultural frameworks.

Butler’s feminist theory, on the other hand, focuses on the construction of gender performativity and its reinforcement of hegemonic norms within cultural artifacts. She argues that “This is not a subject who stands back from its identifications and decides instrumentally how or whether to work each of them today; on the contrary, the subject is the incoherent and mobilized imbrication of identifications; it is constituted in and through the iterability of its performance, a repetition which works at once to legitimate and delegitimates the realness norms by which it is produced.” [6]. Here, Butler challenges essentialist notions of gender by highlighting its performative nature, arguing that individuals do not stand apart from their identifications but are rather constituted by them. She contends that subjects are formed through the repetitive performance of gender norms, which simultaneously legitimize and delegitimize the norms that produce them. Butler's emphasis on the iterability of performance suggests that gender identities are not fixed or inherent but are continually enacted and negotiated within cultural contexts. By critiquing the ways in which cultural artifacts perpetuate and reinforce hegemonic norms, Butler sheds light on the ways in which individuals are both constrained and empowered by the performative nature of gender. Unlike Lacan, who emphasizes internal psychological dynamics, Butler interrogates the external manifestations of power dynamics within media narratives, particularly emphasizing how gender norms are constructed and perpetuated.

Lorde's theory of intersectionality diverges greatly from the analyses of Lacan and Butler by integrating the intersecting dimensions of race, class, gender, and sexuality into the construction of individual experiences. While Lacan and Butler primarily concentrate on psychoanalytic and feminist frameworks, Lorde's emphasis on the tangible experiences of marginalized communities injects a critical social and political dimension into her theory. Her work extends beyond mere theoretical discourse to encompass the realities of those situated at the intersections of various forms of oppression.

Similarly, Hall's cultural studies perspective expands the scope of media analysis to incorporate broader social and cultural contexts. In elucidating the concept of marginality within culture, Hall highlights its dynamic nature, asserting that it is not merely a periphery to the mainstream but a space of immense productivity. His assertion, "Within culture, marginality, though it remains peripheral to the broader mainstream, has never been such a productive space as it is now. And that is not simply the opening within the dominant of spaces that those outside it can occupy. It is also the result of the cultural politics of difference, of the struggles around difference, of the production of new identities, of the appearance of new subjects on the political and cultural stage," underscores the transformative potential inherent in marginalized spaces, challenging conventional notions of cultural hierarchy [7]. While Lacan, Butler, and Lorde focus primarily on individual subjectivity and representation, Hall situates media texts within broader systems of meaning and power. His perspective underscores the interconnectedness of media with societal norms and values, suggesting that media both reflects and reinforces prevailing ideologies.

These theorists offer diverse approaches to understanding identity, representation, and power within media narratives. While their methodologies and emphases differ, collectively, their work deepens our understanding of the complex interplay between identity, representation, and power within contemporary culture.

“This Extraordinary Being”

In this scene from HBO's Watchmen, Lacan's theory of the Mirror Stage could offer more insight into Will's struggles with his identity. Will’s transformation into Hooded Justice, which requires hiding his true racial identity, represents the fracturing of the self in the face of societal pressures. His adoption of a persona that diverges from his authentic self reflects the tension between societal expectations and individual identity. Lacan notes, “The mirror stage is a drama whose internal thrust is precipitated from insufficiency to anticipation – and which manufactures for the subject, caught up in the lure of spatial identification, the succession of phantasies that extends from a fragmented body-image to a form of its totality that I shall call orthopedic – and, lastly, to the assumption of the armor of an alienating identity, which will mark with its rigid structure the subject’s entire mental development,” [8]. Through Lacan's lens, this transformation represents a moment of internal conflict, as Will grapples with the dissonance between his true self and the image he must present to navigate a racist world. Will’s affair with Nelson provides a brief respite from this struggle, offering a glimpse of genuine connection and acceptance. However, the need to maintain the facade of Hooded Justice underscores the pervasive nature of racial othering and the limitations of individual agency within oppressive power structures. Lacan would likely interpret this scene as an exploration of the complexities of identity formation and the constant negotiation between societal norms and individual authenticity.

As I previously mentioned, Lorde emphasizes the interconnectedness of race, class, gender, and sexuality, arguing that individuals navigate the world not through a single identity, but through a combination of interconnected experiences. For Will, being Black is not separate from being gay; both aspects of his identity shape his experiences of marginalization and oppression.

Lorde would critique the tendency to view oppressed groups through simplified categories. The Minutemen's acceptance of Will as Hooded Justice is conditional – he can be a hero only if he hides his Blackness by wearing the mask. Will can't be a Black hero; he can only be a whitewashed version of himself. This echoes Lorde's critique of how simplistic categorizations often fail to capture the lived experiences of marginalized individuals. Will's struggle for acceptance is further complicated by his homosexuality. He exists within a society where both Blackness and homosexuality are ostracized. The scene hints at a potential space of acceptance with Nelson, but even that's limited. Their intimacy exists in secrecy, highlighting the lack of safe spaces for Will's true self. Lorde would likely argue for the importance of solidarity and coalition building across marginalized communities. While Nelson's "tolerance" of Will's race might seem like a step towards acceptance, Lorde would challenge this notion. True progress requires dismantling the very system that necessitates such toleration. The Minutemen themselves represent a system that upholds white supremacy, making them an unlikely vehicle for true social change. Will's fight for acceptance cannot be separated from the larger fight for systemic change, a point Lorde would strongly emphasize.

Butler, open the other hand, would likely analyze how Will and Nelson's performances of masculinity intersect with race and power dynamics. Nelson, as a white man, embodies the dominant form of masculinity associated with heroism. Will, on the other hand, must subvert his own Black masculinity to fit the mold. Butler's theory acknowledges the possibility of subverting societal norms through performance. However, the scene exposes the limitations of this subversion within a system of oppression. Will's performance as Hooded Justice can be seen as a form of resistance – he challenges the expectation of a white hero. Yet, this resistance is severely limited. He can only participate by hiding his true self, suggesting that true acceptance for a Black hero is still missing. The mask can be interpreted in two ways through Butler's lens. On one hand, it's a cage that forces Will to conform to a limited definition of heroism. On the other hand, it can be seen as a tool – a way to infiltrate the system and potentially dismantle it from within. However, the scene offers little hope for this possibility. Nelson's "tolerance" is fragile and dependent on Will performing whiteness. This highlights the difficulty of using performance as resistance within a deeply entrenched system of racial prejudice. Butler might argue that the scene ultimately exposes the need to move beyond performance altogether. The true act of resistance would be to dismantle the societal norms that require Will to wear a mask in the first place.

Finally, Hall would likely analyze how the scene reflects broader cultural narratives around race and power. He might question the ways in which the portrayal of Will's struggle with identity reflects broader societal attitudes towards race, and how these representations shape perceptions of blackness in popular culture. Furthermore, Hall's work highlights the importance of critically engaging with representations of race and identity in media, as they both reflect and shape societal perceptions and power dynamics.

“A God Walks into Abar”

From a Lacanian perspective, Dr. Manhattan's choice to inhabit Cal's body touches on the complex layers of identity formation, societal norms, and expectations. Lacan's Mirror Stage theory suggests that individuals develop their sense of self by identifying with external images. The decision to become Cal reflects Dr. Manhattan's negotiation of his own sense of self within the context of Angela's desires and broader societal constructs of race.

Evidently, Angela’s preference for Dr. Manhattan to inhabit a Black body stems from a complex web of identity and power dynamics. As a Black woman, her life has undoubtedly been shaped by the realities of racism. Choosing a Black partner can be seen as an act of self-preservation, a desire for intimacy with someone who understands, at least to some degree, the experiences that have shaped her. Lorde would likely commend Angela's agency in asserting her desires within a relationship.

From Hall's perspective, Angela's preference for a Black partner in "Watchmen" resonates with broader human tendencies seen both in real-life relationships and in media consumption. Hall's theories on cultural identity highlight the importance of representation in shaping individuals' understanding of themselves and others.

So, in this context, Angela's desire for a Black partner mirrors the universal human inclination to seek relatability and connection with others who share similar backgrounds or experiences. Just as people naturally gravitate towards those who reflect their own identities in interpersonal relationships, they also seek representation and resonance in the media they consume.

However, Dr. Manhattan's transformation represents the power dynamics at play, particularly in relation to race and privilege. As a white man with god-like abilities, Dr. Manhattan’s decision to inhabit and take Cal's body raises questions about the appropriation of marginalized identities and the implications of such actions.

Lorde's critique would likely focus on this situation. Cal, a deceased Black man, has no say in Dr.Manhattan inhabiting his form. This raises troubling questions about power dynamics. Dr. Manhattan, an originally white superpowered being, essentially takes over a Black body to fulfill his own desires and appease Angela's preference. Cal's individual identity and history are erased, replaced by Dr. Manhattan's assumption of a Black form. This act can be seen as a microcosm of larger societal issues, where dominant groups appropriate aspects of marginalized identities without fully understanding the complexities of those experiences.

When Dr. Manhattan inhabits Cal's Black body, he engages in a deliberate act of performance. He adopts a racial identity that wasn't previously associated with him. This act resonates with Butler's idea that identity is a continuous process of "doing" – in this case, "doing" Blackness. Butler would likely critique the appropriation of Cal's body. She would argue that this act echoes a colonial dynamic, where the powerful take over and utilize the bodies of the marginalized. Does Dr. Manhattan truly understand the lived experience of being Black, or is he simply performing a racial identity for convenience? The scene pushes the boundaries of Butler's performativity theory. While Dr. Manhattan performs Blackness, can he truly embody the lived experience of being Black? Butler might argue that performance has its limitations. One can perform an identity, but this doesn't equate to a full understanding of the historical, social, and cultural contexts that shape that identity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the application of Lacan's Mirror Stage theory, Butler's concept of gender performativity, Lorde's intersectional approach, and Hall's cultural studies perspective to Watchmen provides a rich understanding of identity, representation, and power dynamics within the show's narrative. These theories offer nuanced insights into characters' struggles with societal expectations, the appropriation and resistance within systems of oppression, the complex interplay of race, gender, and desire, and the broader societal attitudes reflected in racial representations. By applying these perspectives, we deepen our comprehension of the show's themes and characters, highlighting the complexities of identity formation and representation in contemporary media.

Works cited

[1] Lacan, “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I,” 3.

[2] Butler, “Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion,” 339.

[3] Lorde, “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference”, 115.

[4] Hall, “What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?" 472.

[5] Lacan, “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I,” 2.

[6] Butler, “Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion,” 343.

[7] Hall, “What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?" 470.

[8] Lacan, “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I,” 3.

0 notes

Text

How do Aguilera and Lil Nas X negotiate their multiple identities within the contexts of their respective music videos?

Race and Representation Music Video Analysis

For my panel discussion I will be analyzing Christina Aguilera’s “Can’t Hold Us Down” music video which ignores the power of the images within its video and the power that Aguilera has in relation to the cultures she is adopting and representing. I will also be analyzing Lil Nas X’s “Industry Baby”, which I believe attempts to provide an alternate look at stereotypes, not through a commitment to “actuality” or “positive images”, but through the experimental heightening of contrasting stereotypes about the black gay man that reveal their contradictory and arbitrary nature.

youtube

Christina Aguilera’s “Can’t Hold Us Down” music video was produced as part of her Stripped album, which was centered around a more provocative image. The song is focused on feminism with the echoing lyrics of “this is for my girls all around the world”, yet by focusing just on feminism, it markets the experiences of all women as the same, when race and other factors affect experiences. Christina Aguilera, a white passing Latina woman, fails to acknowledge the difference in her experience as a women from all the “girls around the world” while the representation within her music video, particularly her own image which is constructed from ghetto stereotypes of black or Latino womanhood.

(from Left to Right) at 00:20 establishing shot shows men in front of mural mentioning crack. Grocery cart filled with trashbags (implied homelessness or poverty) are in foreground. The foreground and background of this shot simplifies and established the nature of these characters- ecliped by their identity of poverty with the possibility of illegal activity always hanging over them.

At 00:06, Christina Aguilera is introduced on the steps of the dirty curb (objects are literally being thrown down) while surrounded by Latina and Black women. Aguilera is passing herself off as one of the community, but as the star of the video and a pop star she holds all the power in the following representation of these women.

The music video starts out with establishing scenes of the urban setting filled with graffiti, dilapidated buildings, and people lounging/playing around ever corner. The assumption the audience is supposed to reach plays upon stereotypes and ideas already implemented by hegemonic culture [1]. This is a portrayal of the ghetto or the gritty and unkempt. This setting allows the later behavior we see, particularly that of the men, which is supposed to represent a particular uninhibited nature, that one may not expect to see as unmasked in a suburban (read white) area.

Aguilera is using these stereotypes, of the unruly and over sexualized black man in the ghetto, and her own hyper-sexualized image of herself residing in the ghetto to give herself and the overall music video a sense of grittiness or provocativeness. Its supposed to come as a jarring departure from her previous work, as if stepping closer to Black pop-culture allows her to claim an edge which she can (and did) leave behind when the image is no longer as monetarily valuable.

Compared to her earlier works, one can see that she adopts the stereotypes and culture of Black and Latina women to appease a certain "spectatorial fascination" audiences may have [2]. There is- as seen in many films, TV shows, and also the attitudes of certain people online- a fascination with the ghetto- a place that is the intersection between minority races and lower class (as in economic) status. There is a power in watching the ghetto while allowing the distant image of the ghetto to be relegated to perversion and unseemliness.

The way that pop culture portrays the ghetto can be compared to Edward Said's example of the studies and portrayals of the Orient or Ella Shohat's and Robert Stam's many elaborations on films about the Third World. The assumptions about the ghetto have eclipsed the social reality of it, and it is paradoxically admonished and then revered (out of fascination for what has been admonished). Stuart Hall defines this as the "modernist construction of primitivism, the fetishistic recognition and the disavowal of the primitive difference" [3]. There is the fascination with a supposed primitive or simpler nature, but the underlying admission that it is inferior or unpractical. Aguilera's power in terms of identity politics places her in a position that allows her to benefit from fascination from the scene she is portraying while always letting the audience know that this isn't who she is; she never faces the admonishment. Meanwhile, opinions of the other background characters in the video may be generalized and due to the weight that minority representations have, contribute further to negative images of certain groups.

Question:

While it is clear that Aguilera's urban setting is a selective appropriation of culture and stereotypes, it can't be denied that it is somewhat connected to a social reality, one that is steeped in imposed social, political, and economic difference. If "positive images" potentially ignore realities and obstacles to the black experience, how is meaningful representation created? In your opinion, how much meaning is their in 'truthful' representation and to what extent is that possible?

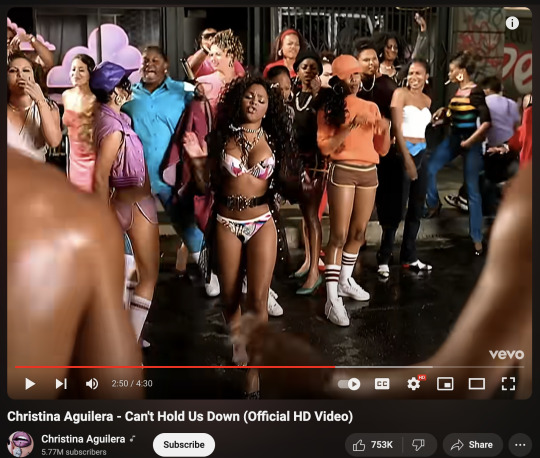

One of the groups that suffers immensely from this video is that of Black men. The video is centered around feminism and the sexual harassment that women face. It is, however, hard to separate this message from the identity politics and racial power that Aguilera has over nearly everyone in the video. The person who gropes her in the beginning is a black man, thus perpetuating unseemly stereotypes that come from the caricature of the sexually and racially intimidating "buck" [4]. It is the unruly and extremely sexualized Black man who assaults the white women and who must be admonished.

The particular choice of who is the assaulter and the assaulted plays into already created social schemas due to the (American) audience living in the inescapable context of the dominant cultural hegemony- which continues to refract itself. Through the groping it is suggested that the man is dominating the woman, but through the larger meta lense of this video, Aguilera is dominating the representation of the Black man.

Question:

What is the responsibility of Aguilera and the creators of this music video when acknowledging the harmful stereotypes it perpetrates from Black men? How could the intersectionality of identity politics have been better addressed while still maintaining its message about the sexualized or inferior role imposed upon women?

In regards to the Latina and Black women that Aguilera is supposedly upholding, they are for the most part relegated to the background. There is a power balance that is communicated through this [5]. Through this diminishing of their importance and the centrality of Aguilera (who is then hyped up by other women), Aguilera becomes this mediating presence who is meant as a stand-in (immediate representation) for the audience but also as the confronter of the power dynamic the men have over the (other) women [6].

At 1:50: When other women are put in the foreground, facial expressions or seeming characteristics (sassiness, sexuality, or being a good dancer) are highlighted. This plays into racialized stereotypes of the sassy hyper sexualized Black women (something that Aguilera is trying to portray herself as) or the passionate Latina dancer [7].

There is the particularly troubling scene with Lil Kim (who I noticed is not credited in the video title as featuring unlike the video in the queue that credits Redman). While Aguilera is adopting blackness and the characterized sexiness, tanned skin, and style of it, Lil' Kim. After being front and center, Aguilera essentially gives up some space to Lil' Kim- a sign of reverence. Lil' Kim's outfit stands out as more sexualized than the rest with more skin showing. She is portrayed as the epitome of stereotyped ghetto blackness- sexually confident (perhaps aggressive) in skimpy clothing. Unlike Aguilera, who is protected by her whiteness so that the audience distinguishes her character in the video from reality, Lil' Kim's representation becomes not only who she is, but who all urban Black woman are.

In the scenes where Christina uses the hose on the men, it is a symbolic power move where the hose plays the role of the penis. It should be noted, however, that Aguilera continues to be the one to take action against the men, as afforded by her stardom but also her role within the racial hierarchy. Someone else gets the hose only when she finally steps away. The video is ending and she gets to leave the ghetto, but the representations of Latino/a and Black women/men does not get to leave.

youtube

In contrast, Lil Nas X's "INDUSTRY BABY" provides an opportunity to focus less on images than that of discourse. Simply by Lil Nas X existing and making this video there is the relaying of a unique voice and perspective that is typically sidelined. Additionally, Lil Nas X's intersection of identity is never forgotten since it is intrinsically tied together that he is black and gay.

What makes this important representation (not a 'positive image') isn't that what is displays is some kind of authenticity, but rather the prompting of discourse it provides [8]. It fights stereotypes through subversion or even nodding to them, causing the audience to reckon with the naturalization of the original stereotypes. This can be seen by setting the video in prison. Clearly, what is shown in the video is not the reality of prison (such as the costumes), but it takes what is the reality combined with assumption to create subversion.

Lil Nas X takes what is expected to be a very masculine place and is able to portray it as a queer place of joy and camadarie. Usually, when there is queerness in prison it is assumed to be an act of violence that enforces heteronormativity. The isolation of the prison as well as the criminality of prisoners supposedly drives them to homosexuality. Meanwhile, there is also the obvious visual fact that Lil Nas X and many of his companions in the video are Black. The violence (particularly sexual) that is characteristic of Black caricatures comes to forefront in the prison. If the Black men were bad in the ghetto they will be terrible in prison.

There is the complex intersectionality of multiple caricatures- the violent man in prison who resorts to homosexuality, the violent black man in prison who resorts to homosexuality, and the gay black man- who is supposedly feminine and meant (in a prison setting like this) to be dominated.

Stuart Hall talks about the potential trap of black pop culture, which often packages commodified stereotypes as "the arena where [they] find who [they] really are" since "it is only through the way in which [they] represent and imagine [themselves] that [they] come to know how they are constituted and who [they] are" [9]. It is difficult for a black man to overcome pop culture's image of him by over-attributing lived experience as a homogenous representation [10].

Yet Lil Nas X has always had to face his own personal rupture of the masculine identity of the black man because of the feminine identity of the gay man. It is this rupture that makes him a unique voice to listen to as he is not as trapped by the constraints of the dominant hegemonic view because of how it particularly carved out the identity (and exclusion) of the black gay man. He does not have to be made aware of the positionalities because he has always resided within a precarious intersection.

The prison can be seen as a metaphor for the very masculine world of hip hop that Lil Nas X inhibits- which matches the lyrics of his song which condemn those who sun him or believe that he can't make it in the industry because of his identity (adding the queerness on top of the hip-hop accepted blackness).

From 0:36; This scene takes a particular setting that refers to the sexual violence of prison and turns it into a performative stage of dance, a use of the body which Hall says is "the only cultural capital we had".

While many of the background dancers in scenes are black, they are not put into the background because of Lil Nas X's own identity as a black queer man. There is no inherent power dynamic besides that of Lil Nas X being the singer. The racial positionally and dominance of Aguilera's video is not present here [11].

There is perhaps the question of the misrepresentation of women because of the lack of women except for one scene where Jack Harlow seduces a warden. Shohat and Stam mention how Do the Right Thing runs into a similar representational issue with its absence of a feminist voice [12]. Hall notes the importance of diverse voice because of the impossibility of the homogenity or universality to any discourse. Since the video is such a analysis of masculinity, women have no place except to establish Jack Harlow's (assumed) powerful positon of a white heterosexual male. This is then subverted when it is Lil Nas X who electrocutes Harlow on the chair, as, in reality, the amount of black men sentenced to death is larger than others.

Question:

What does the video say about performative gender? Is there an intersection between performative gender and performative racial stereotypes? Or is there more of a social economic basis for the latter?

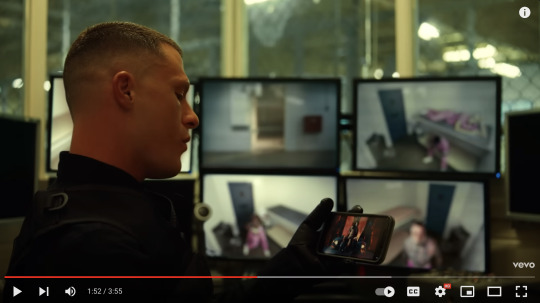

At 1:52; The sequence where a security guard is watching Lil Nas X's "Montero" video (which he is sent to this jail in this video for) right before Lil Nas X knocks him out plays with the idea of media consumption and commodification of the black rapper. It is very important this guard is white, because his dominant positon (as a white male and as the prison guard) allows him to look down upon Lil Nas X while also using him for enjoyment. To this guard (and to many audiences) the black (gay) man is a source of entertainment or a threat.

Overall, the "INDUSTRY BABY" does a better job with representation, not because it conforms to positive images that are palatable to mainstream moral conscious, but because of Lil Nas X's identity and how the video stays true to the intersection of his identity rather than trying to commodify certain stereotypes (especially ones that aren't true to him).

QUESTION:

What is the responsibility creators from dominant cultural positions of power have when promoting or working with people within marginalized groups?

Citations

[1] Edward Said, "Knowing the Oriental", in Orientalism (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978), 34.

[2] Ella Shohat and Robert Stam, "Stereotype, Realism and the Struggle Over Representation", in Unthinking Eurocentrism (London: Routledge, 1994), 188.

[3] Stuart Hall, "What is this 'black' in black popular culture?", in Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies (London: Routledge, 1996), 470.

[4] Shohat and Stam, 195.

[5] Shohat and Stam, 208.

[6] Shohat and Stam, 189.

[7] Shohat and Stam, 196.

[8] Shohat and Stam, 214, 215.

[9] Hall, 476, 477.

[10] ibid.

[11] Hall, 471.

[12] Shohat and Stam, 214.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

How do the aesthetic choices (like doing a doc-style or sitcom-style video) contribute to the videos' overall impact and effectiveness in conveying their intended messages?

Discussion Leader Panel Presentation - Race and Representation

youtube

While the song “Can’t Hold Us Down” by Christina Aguilera1 is mostly about female empowerment and resisting gender stereotypes, the music video conveys even more, with stark imagery of a community that is made up primarily of people of color. The intersectionality that the video possesses is key to understanding its message. In Stuart Hall’s essay “What is this ‘black’ in black popular culture?2,” he introduces his idea that the “Black” in Black popular culture is not a set idea, rather it is a fluid conversation of Blackness. In his words, “What we are talking about is the struggle over cultural hegemony, which is these days waged as much in popular culture as anywhere else”3. While, as I stated earlier, on the surface this video is about what it means to be a woman, its underlying themes are of race and representation, which is the real battle being fought. This intersectionality is still key to Hall’s philosophy. As he says, “We are always in negotiation, not with a single set of oppositions that place us always in the same relation to others, but with a series of different positionalities”4. Aguilera’s exploration of themes of sexuality while using the backdrop of a primarily people-of-color community is this video’s way of continuing the conversation about what it means to be “Black”, or in the video’s case, simply “other”. “The Other” is a concept Edouard Edward Said introduces in his seminal book Orientalism5. In the context of the Orient, better known as Asia, he states that “The Orient is not only adjacent to Europe; it is also the place of Europe’s greatest and richest and oldest colonies, the source of its civilizations and languages, its cultural contestant, and one of its deepest and most recurring images of the other”6. He goes on to say that Europe sees Asia as “its contrasting image, idea, personality, experience”7, yet it is “an integral of European material civilization and culture”7. While Aguilera’s video does not explicitly speak about Orientalism, some key themes are very present. In Orientalism, Said refers to the way Asia is perceived as “‘a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences”6. Essentially, Orientalism places emphasis on the mystification of Asian culture, through the power of European colonialism. The environment Aguilera’s video is set in is extremely colorful, and, as previously mentioned, mostly populated with people of color. Most of the very few white people in this video appear in the beginning, shown throwing milk into the street below. This can be seen as a representation of Orientalist themes. The white people are placed above the people of color who populate the streets below, and throw milk onto them, which can represent the Orientalist turn of imposing Euro-centricity on the culture of those colonized and disenfranchised.

Of course, the question must be asked, is this music video an authentic representation of the culture and community that it’s presenting to us? In their book Unthinking Eurocentrism8, Ella Shohat and Robert Stam consider the way that race and representation exist in the media. Under the section “Writing Hollywood And Race” in the chapter “Stereotype, Realism And The Struggle Over Representation,” they argue that there is an important distinction between media image and social reality. They use the documentary Color Adjustment to help their argument, stating that “Color Adjustment underlines this contrast between media image and social reality by suggestively juxtaposing sitcom episodes with documentary street footage”9. I’d like to pose the thought that perhaps Aguilera’s video would fall under the category of sitcom in this comparison, at least when it comes to the ideas of race and representation. Aguilera, who is of Ecuadorian, German, Irish, Welsh, and Dutch descent, did not grow up in people of color dominated areas of New York. She lived in Wexford, PA for most of her adolescence, a town in a majority-white county. This music video may feel inauthentic to many because it may not be authentic to Aguilera’s experiences. Which brings me to Kendrick Lamar

youtube

Kendrick Lamar grew up in Compton, CA, at a time when the city’s high crime rates were national news, due to the prominence of gangster rap groups like NWA. The music video for his song “i”10 showcases this environment prominently. From the cars to the police uniforms, the video harkens back to a time when Kendrick was growing up in South Central Los Angeles. In my estimation, Kendrick Lamar’s video represents more of the “documentary footage” that Shohat and Stam mentioned in their comparison with media image and social reality. Aguilera’s video can be felt as inauthentic because it feels like a sitcom, not in a comedic way but in a matter of faux reality. Kendrick’s video feels like a documentary because of its groundedness in his childhood and the experiences of his city. It should be noted that Aguilera appears to darken her skin in her video. As previously stated, Hall believes that popular culture is a place where the concept of “Black” is able to be conversed about. Kendrick, in his music video for “i”, is able to redefine “Blackness” on his own terms. He presents different depictions of Black characters in every moment. One moment that shows great contrast of character and incredible conversation in his own mind on the topic of “Blackness” comes at the 2:20 mark in the video for “i”11.

Kendrick walks past a house, on the front porch of which a man yells at a woman; presumably they are in a relationship. In this very same moment, two Black children, one boy and one girl, run by, playing together, juxtaposing the depiction of adult negativity behind them. There are many things that can be interpreted from this shot, which perhaps even greater lends itself to the argument that it is more “documentary footage”. The perceived authenticity of Kendrick Lamar’s “i” video thus lends itself to a challenge of Orientalist ideals. While the video does show White police officers arresting a Black man at 1:4312, seemingly exerting that idea of power over “the other” that Orientalism is built so much upon, it is immediately followed by Kendrick and his crew of dancers/partygoers weaving through the group of cops with numbers that far outweigh what the cops possess, thus re-establishing power over themselves.

Works Cited

1Aguilera, Christina. “Christina Aguilera - Can’t Hold Us Down (Official HD Video).” YouTube, November 18, 2009. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dg8QgUIKXHw&t=196s.

2Hall, Stuart. “What Is This ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?” Essay. In Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies. London, United Kingdom: Routledge, 1996.

3Hall. “What Is This ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?”, 471

4Hall. “What Is This ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?”, 476

5Said, Edward. “Introduction.” Essay. In Orientalism. London, United Kingdom: Routledge, 1978.

6Said. Orientalism, 9

7Said. Orientalism, 10

8Shohat, Ella, and Robert Stam. “Stereotype, Realism And The Struggle Over Representation.” Essay. In Unthinking Eurocentrism. New York, NY: Routledge, 1994.

9Shohat and Stam. “Stereotype, Realism And The Struggle Over Representation”, 198

10Lamar, Kendrick. “Kendrick Lamar - i (Official Video).” YouTube, November 4, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8aShfolR6w8.

11Lamar. “i”, 2:20

12Lamar. “i”, 1:43

Discussion Questions

Can the darkening of one’s skin make the work feel more authentic, and when might this backfire?

Does either video engage in stereotype, and if so, does it detract from the video or benefit it?

Is fair to compare the music videos for these songs, though the lyrics of the songs convey such different messages, and can a music video change a son’s message?

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

What role does imagination and speculative fiction play in envisioning alternative realities and challenging existing power structures, like in the Q.U.E.E.N video?

Panel Presentation: "Telephone" by Lady Gaga ft. Beyoncé & "Q.U.E.E.N." by Janelle Monáe ft. Erykah Badu

By Sophie Goldberg

youtube

"Telephone" by Lady Gaga ft. Beyoncé

The music video Telephone by Lady Gaga ft. Beyoncé serves as a continuation of "Paparazzi", where Gaga was arrested for killing her abusive boyfriend by poisoning his drink. It features a storyline where Lady Gaga is imprisoned but eventually escapes with Beyoncé's help, and they then go on to poison Beyoncé’s boyfriend and others in a diner and run from the police.

Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”

Mulvey discusses the concept of the male gaze, where the camera represents the perspective of a heterosexual male viewer, objectifying female characters for the pleasure of the male audience. Beyonces and Lady Gaga’s portrayal aligns with certain aspects of the male gaze. The music video inevitably attracts male attention as the camera frequently lingers on their bodies and costumes, emphasizing their sexuality and allure. Mulvey states “Traditionally, the woman displayed has functioned on two levels: as erotic object for the characters within the screen story, and as erotic object for the spectator within the auditorium” (716). For example, when Lady Gaga first enters the prison everyone is wearing revealing clothes, and as she's pushed into her cell officers strip her down, leaving her with nothing but fishnets. Another instance occurs when Lady Gaga and three other women wear studded bikinis and engage in a provocative dance down the prison corridors. Spectators also see them through the lens of a security camera, furthering the voyeuristic aspect.

However in "Telephone," both Lady Gaga and Beyoncé also challenge traditional notions of passive femininity by taking on assertive, dominant roles. Mulvey states that “pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female’ (715). Women are presented as spectacle as the man's role is “the active one of forwarding the story,” (716) Lady Gaga and Beyoncé disrupt traditional narrative conventions by defying societal expectations of female passivity and instead taking control of their own narrative. Gaga and Beyoncé portray themselves as empowered and even dangerous figures as in the music video there are depicted acts of violence against men.

Bell Hooks, “Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators”

Hooks discusses how Black female spectators often engage with media representations critically as “ mass media was a system of knowledge and power reproducing and maintaining white supremacy. To stare at the television, or mainstream movies, to engage its images, was to engage its negation of black representation.” (308) In "Telephone," Beyoncé's confident demeanor, assertive actions, and her role as the one with more agency than Lady Gaga—having the power to bail her out of jail—can be viewed as empowering examples of Black women asserting their autonomy within mainstream media.

Furthermore, Hooks critiques mainstream media for its tendency to eroticize and objectify Black women's bodies. In the video, there is a moment in which there is a high angle shot of Beyoncé's cleavage as she sits across from her boyfriend in the diner. Although, within the framework of the oppositional gaze, Beyoncé's character adopts a rebellious stance, refusing to conform to the gaze of desire and possession. Instead, she asserts her power by poisoning her misogynistic boyfriend and evading the police.

Audre Lorde, “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference”

In Lorde's essay, she states “As women, we must root out internalized patterns of oppression within ourselves if we are to move beyond the most superficial aspects of social change.” (122) One such pattern is internalized misogyny, where women devalue themselves and others, which can lead to judgmental attitudes towards different lifestyles and choices. In "Telephone," Beyoncé exemplifies Lorde's words by not passing judgment on Lady Gaga's choices when she bails her out of jail. Despite their differing lifestyles, they unite against a common oppressor. Furthermore, societal expectations surrounding gender roles can also be internalized forms of oppression, such as conforming to domestic responsibilities. In the video Lady Gaga challenge these norms when she incorporates the stereotype of women in the kitchen within a segment titled “Lets Make a Sandwich”, but instead of adhering to these norms she instead puts poison in all of the food.

Furthermore, Lorde underscores the need to recognize differences among women as equals , relate across the differences, and utilize them to enrich collective visions and struggles. This is shown in the music video through the camaraderie and alliance depicted between Lady Gaga and Beyoncé. The video embraces diversity within feminism, showcasing representations of differences in sexuality and race, yet emphasizing a shared goal of empowerment. This sentiment is also echoed in the lyrics, “Boy, the way you blowin' up my phone , Won't make me leave no faster, Put my coat on faster, Leave my girls no faster”

youtube

"Q.U.E.E.N." by Janelle Monáe ft. Erykah Badu

Janelle Monáe's music video for 'Q.U.E.E.N.,' featuring Erykah Badu, serves as a freedom anthem within a science fiction dystopia. The title itself, 'Q.U.E.E.N.,' is an acronym representing marginalized communities: Queer, Untouchables, Emigrants, Excommunicated, and Negroid, reclaiming royal imagery to challenge traditional hierarchies of race, sexuality, and class. Monáe's Afrofuturist vision suggests a revolution, where marginalized communities and differences are celebrated rather than ostracized. The music video features rebel time-travelers that are frozen in a museum and brought to life by music. In the video's narrative, the song functions as part of a “musical weapons program” that disrupts the status quo, allowing the rebels to move through history and forge a new future in the present.

Laura Mulvey “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”

Mulvey argues that traditional cinematic narratives often reinforce patriarchal ideologies and power structures as they cater to a male gaze. The music video "Q.U.E.E.N." offers a narrative that challenges this as it features strong, empowered female protagonists who challenge traditional gender roles and expectations. Janelle Monáe wears a black-and-white tuxedo, disrupting the traditional notion of gendered clothing styles. The ladies all dance with each other and build eachother up such as when they reply and affirm each other “Is it peculiar that she twerk in the mirror? And am I weird to dance alone late at night? (Nah) And is it true we're all insane? (Yeah) And I just tell 'em, "No we ain't" and get down”. Here, the mention of twerking in the mirror is not sexualized but used to empower the female body.

Bell Hooks, “Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators”

The oppositional gaze is seen in the music video as Black female spectators engage with the visual representation of empowerment and resistance depicted in the video. Monáe uses both queerness and Blackness as examples of modern “freakishness.” Monáe doesn't assign a "freaky" status to queerness or Blackness herself, instead, she challenges listeners to interrogate why these identities are perceived as "freaky." She suggests that what society deems as "freaky" is simply the act of being true to oneself. The lyrics declare those differences as things to be proud of stating "Even if it makes others uncomfortable, I will love who I am". Monáe and Erykah Badu illustrate the way society "freakifies" their Blackness, showcasing how joy and celebration within Black culture are often viewed negatively due to racist stereotypes. The hook in the song highlights this, asking: “Am I a freak for dancing around? Am I a freak for getting down? I’m cutting up, don’t cut me down.” Black female spectators can find empowerment in seeing how the song recognizes differences and individuality as prideful assets.

Audre Lorde, “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference”

Lorde emphasizes the importance of recognizing the intersections of age, race, class, and sex in understanding women's experiences. The video highlights the oppression faced by diverse identities and experiences of Black women, as well as showcases their resilience in the face of it. The lyrics “Add us to equations but they'll never make us equal” resonates with Lorde’s claim that simply incorporating marginalized groups into existing systems does not address the underlying power imbalances or inequalities. Monáe’s next lyrics recognizes these inequalities stating “She who writes the movie owns the script and the sequel, So why ain't the stealing of my rights made illegal? They keep us underground working hard for the greedy, But when it's time pay they turn around and call us needy (needy)” Lorde further advocates for collective action and solidarity among women of different backgrounds to achieve liberation. In "Q.U.E.E.N.," the song's message of female empowerment and solidarity is highlighted as Monáe and Badu come together to celebrate different identities, for example sexual and racial identity. Janelle Monáe promotes unity and collaboration among women as she says “Will you be electric sheep? Electric ladies, will you sleep? Or will you preach?” According to Janelle Monáe it is up to this community and this generation to create its new norm and break down the walls that limit them.

Discussion Questions:

Lorde says ““By and large within the women’s movement today, white women focus upon their oppression as women and ignore differences of race, sexual preference, class and age. There is a pretense to a homogeneity of experience covered by the word sisterhood that does not in fact exist.” In the music video, do you think Lady Gaga is focusing on the oppression of just women in general and treating the experience of all women the same, or is she not necessarily ignoring the differences but the video just does not explicitly address them .

Is trying to make money and bring attention using our bodies promoting sexism even though it is our choice and feel empowering or confidence boosting

In music videos is using Sexuality and promiscuity still catering to the male gaze even if they are active agents in the narrative? What about in the cinema?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

How do both MVs challenge traditional representations of women's bodies in media, particularly in relation to the male gaze?

Panel Presentation: "Telephone" and "Thot Shit"

youtube

“TELEPHONE” LADY GAGA & BEYONCE

In Lady Gaga’s “Telephone” (ft. Beyonce) music video, she centers two women criminals, half of the video taking place at a women's prison and the other half following the homicide the women (played by Gaga and Beyonce) set out to commit. The first striking thing about the video is the immediate use of women’s bodies. All the women in the prison are wearing revealing outfits, even the women security guards. As Gaga walks down the cells, the fellow prisoners (all female-presenting) hoot and holler and as character is thrown into her cell, the guards promptly rip off her clothes. This is an example of the use of a woman’s body that is not centering the male gaze. While a male gaze still may derive pleasure from the revealing costumes in the video, these characters are not necessarily designed to be seen as sexy by the male spectator. In Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” she writes that media depictions of women in a patriarchal culture stand as a signifier for the male other - meaning that women characters are present to engage with the male fantasy (1). While most of the women in the music video are partially nude or in revealing costumes, they are not doing so in a sexual nature. Their nudity and sexuality isn’t aiming to please men but to claim their own sexual identity. Mulvey also touches on how women’s bodies in “alternative cinema” can be also a radical or political aspect that challenges the basic assumptions of mainstream media, instead of just being objects for pleasure (2). Women’s bodies are shown in “Telephone” in different ways than usual music videos – there is more of a diversity in beauty and a roughness to them – these bodies are asking to be looked at.

In hooks’ “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” she writes about the “right to gaze.” Specifically, she references: “the politics of slavery, of racialized power relations, were such that the slaves were denied their right to gaze” (3). In these racialized power relations, she writes that Black people were not permitted to engage in the same freedom of watching, entertainment, or deriving pleasure from what they were seeing. This structure ultimately permeates to this day, as hooks writes that of the Black women she spoke to, none were excited to attend the movie theaters, knowing they would not be properly represented (4). How “Telephone” works in contrast with this trend is allowing spectators to look at and derive pleasure from the woman’s body. The idea of the oppositional gaze is a major part of the video because it challenges the ideas of dominant images that women must conform to. The video’s way of resisting the hegemonic gaze was to place the power into the hands of the women characters and for their bodies and strength to be shown without comparing it to that of a male character. hooks references Manthia Diawara to talk about the power of the spectator: “Every narration places the spectator in a position of agency; and race, class and sexual relations influence the way in which this subjecthood is filled by the spectator” (4) (309). Each person, specifically women, watching this music video could feel a sense of agency after experiencing women characters having power over their own bodies.

On the topic of bodies, the music video employs a semi-diverse cast of women in the video (the majority of women in the video are still white). Specifically, a lot of the women have stark differences about them like ethnicities, age, or sexual identity. In Audre Lorde’s “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” she writes that emphasizing differences is usually taught to be bad or ignored, “or to view them as causes for separation and suspicion rather than as forces for change” (5). In “Telephone,” the differences between these women in prison or Beyonce and Gaga as criminals is distinctly outlined. It is unclear with what Gaga and the writers of the video were trying to accomplish with the “outsider-ness” of the characters in the video – if they were trying to make them look bad or powerful –but one could argue that these women could fit into the archetype of rebels, not caring about society’s rules for them, and that would empower the viewer. It could also be argued that these women are represented by a stereotype of women in prison: violent, erratic, and their homosexuality coming off as predatory and creepy. Mulvey references those who have stood “outside the circle of this society’s definition of acceptable women; those of us who have been forged in the crucibles of difference” (6). “Telephone” puts examples in its video of women on the “margins of society,” but their purpose of being there is unclear to the viewer.

Questions:

Do you think that the other women in the video are meant to be powerful or other-ed, just perpetuating a stereotype?

Do you think “Telephone” practices using the “oppositional gaze”?

How do you think the sexual nature of woman characters in the video differs from other media depictions we have seen?

youtube

“THOT SHIT” MEGAN THEE STALLION

At the beginning of the “Thot Shit” music video, the character of the senator is shown leaving a hate comment on one of Megan’s former music videos (“Body”). When he receives a phone call from Megan she tells him “the women that you are trying to step on are the women you depend on. They treat your diseases, they cook your meals, they haul your trash, they drive your ambulances, they guard you while you sleep. They control every part of your life. Do not fuck with them.” This quote is then the theme for the rest of the video. As the senator tries to escape, Megan and her dancers have taken over every occupation and are dancing in his face. Something interesting in this video is the idea of scopophilia that the senator is taking part in. While he is at first closing his blinds and leaving hate comments before gazing, now Megan and her dancers are forcing him to look, owning their image. Mulvey writes about scopophilia in media/cinema, especially tasteful/pleasurable looking (7). While so much of scopophilia in mainstream media is about privacy and what’s “implied,” it could be argued that Megan is subverting the narrative by using her body and her dancers’ bodies freely and without concerns of what is “forbidden.” It could be seen as an act of agency.

hooks herself may argue that “Thot Shit” is an example of Black women having that sense of agency – the Black women throughout the video have multiple careers while also having the freedom of sexuality. She writes: “Spaces of agency exist for Black people, wherein we can both interrogate the gaze of the Other but also look back, and at one another, naming what we see” (8). This quote encapsulates “Thot Shit” perfectly: a place that Black people can exist freely while also interrogating the gaze of the other. The music video is special because it is a way that Megan celebrates Black women but also the integral part that Black women play in society. They are portrayed as critical parts of a working society but also they dance in the video, owning their sexuality. The sexual nature of the women in the video ties to another example of hooks’ writings about Black women in film/media: the absence “that denies the 'body' of the Black female so as to perpetuate white supremacy and with it a phallocentric spectatorship where the woman to be looked at and desired is ‘white’” (9). hooks writes that too often Black women have been denied ownership and agency over their own bodies, but also the ability to be desired by white phallocentric audiences. By using the character of the senator, they show the inherent racism imposed against Black women - people criticize them but then still sexualize them. Something important to mention is Megan’s lyricism in this song - the word “thot” was coined in the hip-hop world as a derogatory term for a woman, similar to the word “slut,” “with added derision for being working class” (10). The reclamation of this term is outright powerful because it is using a word that has been weaponized against Black women for years and she repurposes it to be something powerful. This subversion in itself can be tied to the work of the oppositional gaze - taking something used to oppress Black women and flipping it to empower them instead.

Rarely in popular media as big as “Thot Shit” do viewers see something with such a clear message. Megan does include a lot of Black female empowerment throughout her music and music videos, especially through sexual agency. Lorde writes, “Black women and our children know the fabric of our lives is stitched with violence and with hatred, that there is no rest. We do not deal with it only on the picket lines, or in dark midnight alleys, or in the places where we dare to verbalize our resistance. For us, increasingly, violence weaves through the daily tissues of our living … ” (11). “Thot Shit” is a form of protesting against the dehumanization and oppression of Black women in mainstream culture. Megan consistently brings Black women into the cultural conversation when they are neglected. Her empowerment is similar to that Lorde writes of: “It is learning how to stand alone, unpopular and sometimes reviled, and how to make common cause with those others identified as outside the structures in order to define and seek a world in which we can all flourish” (12).

Questions:

What are other ways that “Thot Shit” practices scopophilia and voyeurism in nuanced ways?

How is the video different from other music videos you have seen before?

How does “Thot Shit” work in conjunction with “Telephone”?

Works cited:

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” in Film Theory and Criticism, 712. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009)

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” 712

hooks, bell, “The Oppositional gaze: Black Female Spectators” in Feminist Film Theory, 307. (New York: New York University Press, 1999)

hooks, bell “The Oppositional gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 310

Lorde, Audre. "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference." In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, 112. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 2007

Lorde, Audre “Age, Race, Class and Sex: Women Redefining Difference.” (112)

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.”

hooks, bell, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 308

hooks, bell, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 310

O’Neal, Lonnae, “I had a thot but didn’t know it was a thing” The Washington Post, March 19, 2015

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” 119

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” (112)

@theuncannyprofessoro

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why do some people perceive Michael Jackson's changing appearance, as uncanny? How does this perception relate to broader societal attitudes towards race, identity, and self-image?

Psychoanalysis and Subjectivity

youtube

"Thriller" by Michael Jackson, released in 1983, is not just a song but an iconic cultural phenomenon, with its music video setting new standards for the industry. Directed by John Landis, the video is a mini horror film featuring Jackson as a charismatic young man transformed into a werewolf alongside his love interest, played by Ola Ray. The video showcases Jackson's unparalleled talent as a performer, with his electrifying dance moves and mesmerizing presence. Its groundbreaking special effects and narrative storytelling revolutionized the music video medium, becoming an instant classic. "Thriller" remains a timeless masterpiece, captivating audiences with its fusion of music, dance, and cinema, leaving an indelible mark on pop culture for generations to come.

Sigmund Freud's essay "The Uncanny" explores the concept of the uncanny, or the eerie feeling of discomfort or unease experienced when something seems strangely familiar yet simultaneously foreign or unsettling. Freud delves into various aspects of the uncanny, including its connection to repressed desires, the repetition of specific themes or motifs in literature and art, and its association with the return of the repressed. He ultimately suggests that the uncanny arises from the revival of primitive beliefs and fears, often related to death, castration, or the supernatural, which have been repressed into the unconscious mind. This reminds me of the entire motive of the music video, which is the aspect of death. Sigmund said, “the primitive fear of the dead is still so strong within us and always ready to come to the surface at any opportunity”(Freud, 369). Death is the main factor that spikes an uncanny feeling. Our conscious mind feels eerie when we can not define whether something is animate or inanimate. This can also be viewed through the lens of Fenon’s theory because of the transformation, performance, and cultural appropriation that happens in this video. A transformation can be seen as a metaphor for the way Black individuals have been historically portrayed as "other" or different in Western society, often associated with fear and negativity. However, it also ties into Lacan’s theory of identity and self-representation. The transformation can be interpreted as a commentary on the pressure for Black individuals to conform to white standards of beauty and behavior, which makes them see themselves differently because of social interactions.

Question: How often do you see the black community transform into something other than being black, and how much of an impact do you think it has?

youtube