Text

Kaveh Akbar, from “Personal Inventory: Fearless (Temporis Fila)”, Calling a Wolf a Wolf

26K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fantasy Guide to Creating Your Own Language

When writer's set out to world-build, language has a huge role in creating new cultures and lending a sense of realism to your efforts. A world and people just feel more real when language is involved. As the old Irish proverb says "tír gan teanga, tír gan anam”. A country without a language, is a country without a soul. So how can we create one?

Do Your Homework

First things off, you should start by studying languages. Nobody is asking you to get fluent but it's important to understand the basic mechanics of language. You will start to see certain tricks to language, how verbs are conjugated and how gender effects certain words. It will be easier to make up your own when you know these tricks. By immersing yourself in an array of different languages (I recommend finding ones close to how you want your language to sound), you can gain the tools necessary for creating a believable language.

Keep it Simple

Nobody expects you to pull a Tolkien or channel the powers of David J. Peterson (hail bisa vala). You're not writing a dictionary of your con-lang. You will probably use only a handful of words in your story. Don't over complicate things. A reader will not be fluent in your con-lang and if they have to continually search for the meaning of words they will likely loose patience.

Start Small

When you're learning a language, you always start with the basics. You do the exact same when writing one. Start with introductions, the names of simple objects, simple verbs (to be, to do, to have for example) and most importantly your pronouns (you will use these more than any other word, which is why I always start with them). Simple everyday phrases should always be taken care of first. Build your foundation and work your way up, this is a marathon not a race.

Music to the Ears

If your creating a new language, you're more than likely doing it phonetically. Sound is important to language and especially a con-lang because you want to trick your reader into thinking of a real language when reading the words on the page. I suggest sitting down and actually speak your words aloud, get the feel of them on the tongue to work out the spelling. Spellings shouldn't be too complicated, as I said before the readers aren't fluent and you want to make it easier for them to try it out themselves.

Also when you're creating the con-lang, it's important to figure out how it sounds to an unsuspecting ear. If a character is walking down a street and hears a conversation in a strange language, they will likely describe to the reader what it sounds like. It might be guttural or soft, it might be bursque or flowery. It's always interesting to compare how different languages flow in the ear.

Writing in Your Language

Now that you've written your language and created some words, you will want to incoperate them into your story. The way most writers do this is by italicising them. As a reader, I generally prefer authors not to go too overboard with their con-lang. Swathes of con-lang words might intrigue a reader but it can leave them confused as well. It is better to feed con-lang to your readers bit by bit. In most published works writer's tend to use words here and there but there are few whole sentences. For example in A Game Of Thrones by George RR Martin, has actually only a handful of short sentences in Dothraki despite the language being prevalent throughout the book. Daenerys Targaryen pronounces that "Khalakka dothrae mr’anha!"/"A prince rides inside me!" and it's one of the only sentence we actually see in actual Dothraki.

There's also nothing stopping you from just saying a language has been spoken. If you're not comfortable writing out the words, then don't make yourself. A simple dialogue tag can do the trick just fine.

Know your Words

I do recommend keeping an actual record of your words. Make a dictionary if you want or a simple list of words you need. This is one of the most entertaining aspects of world building, have fun with it, go mad if you like. Also here's a short list of questions you can ask yourself about language in general which might help your juices flow.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

when travis mcelroy said “what if you could just cut out the bullshit and do good recklessly?” and when marc evan jackson said “now go do something good” and when chidi anagonye said “i argue that we choose to be good because of our bonds with other people” and when brennan lee mulligan said “you, mortal beings, are the instrument by which the universe cares. if you choose to care, then the universe cares. and if you don’t, then it doesn’t”

52K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writers, please, please, please, I am begging you

I know we don't vibe with Mary Sues, and I know we like watching characters fail...

But if your character is the world's best assassin, they shouldn't be botching nearly every single step of every single job just because the plot demands it. If your character is one of the greatest fighters to ever live, they can't badly lose every single fight the plot throws at them and then barely win the final confrontation. If your character is a competent military strategist, they need at least a few small successes during the course of the plot. If your character is an experienced leader, they can't be constantly making the kind of missteps that realistically would cause their subordinates to lose confidence in them.

If your character is good at something. Show them being good at it.

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

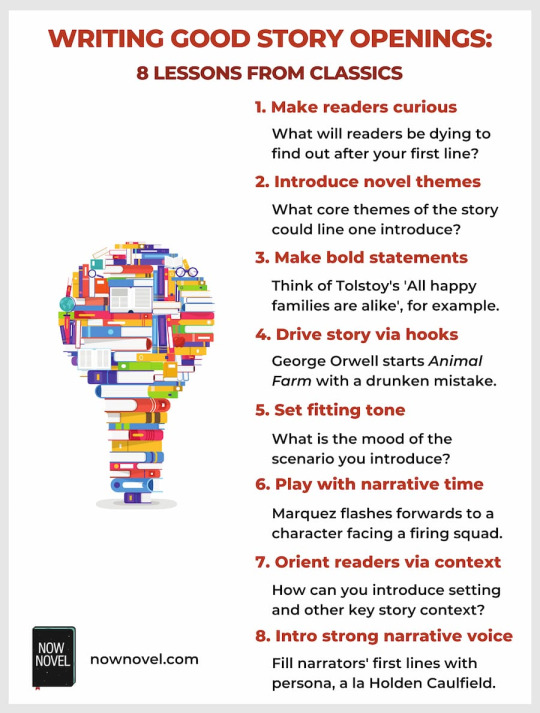

10 Ways to Start your Novel

Here is a collective list of 10 ways to consider starting your story. Merge a couple, use none or just take inspiration:

1) Start in media res or in the middle of an action. This doesn’t have to be an epic battle scene, but instead just means to start with your protagonist in the midst of doing something.

2) Use your unique setting as a hook. If you have a lush fantasy world, a dark dystopian, or even a beautiful contemporary setting, consider opening with some unique descriptions of the location.

3) Begin with a secret or question that your readers want to solve. “Tomorrow, the Serving occurs for the first time in twenty years. I’ll be lucky to survive.” What’s the Serving? Why does it occur once every twenty years? How come the protagonist will barely survive it?

4) Have your antagonist affect the protagonist/plot from the very start. This doesn’t have to be directly, but can be. Think: a step-daughter being excluded at a ball by her evil step-mother. A detective is misled by false clues from the infamous crime lord. A warrior fighting off the henchmen of the main villain.

5) Internal conflict. Readers get to hear your protagonist’s inner thoughts and struggles at the start of the book. Your protagonist might be unsatisfied with life and makes choices that change the story based on their internal struggles.

6) External conflict. Your protagonist is forced to act because of a physical conflict. Whether they cause it, or it’s caused to them.

7) Start with an interesting point of view. If your story has multiple viewpoints, consider starting with a perspective that will really intrigue your audience. Maybe an unreliable, sinister, crazy, or overly anxious character.

8) Create mystery around your characters. Introduce the protagonist, antagonist, or side characters with the intrigue surrounding them. Why does he walk with a limp? Why is her nickname “The Last Resort.”? Harry Potter is the “boy who lived” and Voldemort is “he who must not be named.” These phrases and nicknames create anticipation for the reader to figure out more.

9) Begin with interesting dialogue. In my opinion, opening with typical conversations can be lackluster. Consider starting with the character conversing about a secret, problem, or something unique to your world. Katniss and Gale discuss the Reaping and the Capitol.

10) Create an immersive mood. For example, if you’re writing a dark novel, plunge your reader into an eerie and spine-chilling atmosphere. This tells them exactly what they’re getting into and should expect for the rest of the novel.

Extra Tip) Start with a compelling voice. Show the narrator or protagonist’s unique attitude towards things. Is your narration sassy, dark, romantic, comedic, or something else?

Instagram: coffeebeanwriting

📖 ☕ Official Blog: www.byzoemay.com

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

How to write a gripping beginning

by Writerthreads on Instagram

Personally, I find beginnings to be one of the hardest parts of the whole book because it's so important. The beginning is what makes or breaks your book. It's what keeps readers interested after they pick it up at a store, or when they first download it on their Kindle. Below are some tips, as well as some analyses, on how to perfect a story's beginning.

Introduce your main character and the setting: Mrs. Dalloway

By "introduce", I don't mean a giant 10-page info dump on royal family tree or the ten kingdoms the world is made up of. Rather, I'm thinking of a character in a place, or doing something. The best, and one of the most famous examples would be how Virginia Woolf started Mrs. Dalloway:

Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.

Already, you have the titular character, Mrs Dalloway, introduced. She's doing something, too. She's saying that she's going to buy flowers herself, setting up a scene later where she's probably going to, or back out of, buying flowers. The pronoun "herself" suggests to the reader in Woolf's era that she's of a middle-class background and that somebody (eg. a servant) would normally be running errands for Mrs. Dalloway, but the character wanted to do this simple task herself.

I could go on forever about how each word in this simple sentence has implicit meanings and my ex-A Level Eng Lit teacher will probably be very proud of me, but that's not the point. The main idea is that in just a single sentence, a lot is being revealed to the reader without the writer having to info dump anything.

Allow me to continue to the second paragraph of the book:

For Lucy had her work cut out for her. The doors would be taken off their hinges; Rumpelmayer's men were coming. And then, thought Clarissa Dalloway, what a morning-fresh as if issued to children on a beach.

More characters are introduced now: we have Lucy, Rumpelmayer and his men. Mrs. Dalloway's full name is revealed, and so is her personality through her thought. It's childlike, whimsical and light, and that's why her name "Clarissa Dalloway" is used here instead of the stiff "Mrs. Dalloway".

In just two paragraphs, we are introduced to the titular character and some minor characters are mentioned. We also know bits and pieces of what's going to happen. Woolf artistically starts off the book with simple prose. Everything is well thought out, yes, Virginia Woolf is a literary genius, yes, but this is something that we can all do: write a simple introduction without weighting readers down with lots of detail we don't need, and get straight into the story.

Start in media res

Fun fact: "in media res" is also the name of our Discord Server!

When you start in the middle of an action, readers are transported straight to the story, hooking them in. For example, if you were writing a rom com, you could start with the main character bumping into a long-lost friend:

Emma saw a familiar cowboy hat bobbing in and out of the crowd in front of her. Emma found herself pushing through sweaty limbs into the crowd, trying to catch a glimpse of the person who wore the hat, trying to see whether it was really her friend who had ghosted her five years ago.

Obviously this isn't the best beginning in the world, but you get the point.

Try something interesting

A strong story opening makes you want to know more. Donna Tartt does this perfectly in A Secret History:

The snow in the mountains was melting and Bunny had been dead for several weeks before we came to understand the gravity of our situation.

What is up? Who is Bunny? What's so serious about their predicament? Tell us more!!! Bunny's death makes us want to know what has happened, while mentioning the characters' situation wants us to know what's going to happen. Tartt forces us to continue on to find out the full story.

Lead with a strong statement

A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy:

Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

Tolstoy’s first line introduces the domestic strife that drives the story’s tragic events, using a bold, sweeping statement, while Dicken's catchy first sentence introduces us to the book's main themes.

There are way more examples of good beginnings that you can only learn from by reading. If you're a beginner, literally comb through a library shelf of the genre you're writing in and see how published authors have written their beginnings. Alternatively, you could go check out our post on the best story beginnings for more ideas!

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

I ask god to send a swordsman / and god says ‘look at your hands’

— Melissa Broder in “Problem Area” from Last Sext

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

Tips for Writing Healthy Romantic Relationships

Don’t base them exclusively on physical and/or sexual attraction. While these kinds of attraction can certainly strengthen relationships, they can’t create anything but a weak foundation for a relationship on their own.

Know how your characters like to show and be shown affection. Not everyone shows their interest in others the same way. Some people like to give gifts. Others like to cuddle. Still others like giving compliments. Different people like to receive different kinds of affection as well.

Remember that love at first sight is a myth. You can have lust at first sight and romantic interest at first sight, but true love takes time to develop.

Show the characters interacting and getting to know each other. This should be obvious, but it is all to common for a character to be given a love interest at the last minute or to be paired off with someone the reader hasn’t seen them interact with much. Remember, the reader doesn’t have to see every little thing they do together, but the relationship will feel forced to the reader if they don’t see the characters interacting and establishing that they genuinely care about each other in a significant way. If the reader views your character’s significant other as little more than a stranger, then you’re doing something wrong.

Have both characters do things for each other and contribute to the relationship in meaningful ways. Relationships are two way streets. While you don’t need to keep score of exactly who does what for who (Relationships are not a competitive sport!), the relationship should seem fairly balanced or, if it’s not, then the characters should be working to change that.

Don’t give your characters completely incompatible traits. While it’s healthy for people to differ from each other, there are some differences that even people that are otherwise perfect for each other probably can’t overcome. For example, a environmental activist would have a hard time having a healthy relationship with someone who wants to chop dow a forest. Basically, know your characters’ deal breakers so that you won’t try to match up characters who are simply incompatible with each other.

Have them share interests. This is a great way to add substance to relationships outside of physical attraction and compatible personalities. Maybe they both like fishing. Maybe they share a passion for baking. Whatever you decide to have them like, don’t be afraid to use your characters’ shared interests as opportunities for them to bond. Also, if your characters don’t share a lot of interests/hobbies, consider having one character introduce the other to their hobby or have one character take initiative to try something the other likes. This is a great way to show how much your characters care about each other because it demonstrates your characters’ genuine interest in what makes their partner happy.

Let the relationship experience at least a few bumps in the road. No relationships are perfect. Let your characters disagree, argue, and maybe even have a full on fight. Relationships that withstand obstacles seem stronger to readers, especially if the characters grow as people because of these hardships.

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

How To Avoid Plot Armor

Plot armor is when important characters seem to survive each and every treacherous obstacle that is thrown their way just for the sake of the plot. The readers know that your protagonist is important and won’t meet their demise because who else will defeat the bad guy in the end? This can result in underwhelming battle scenes, loss of suspense and an overall boring experience.

Here are some ways to avoid having your readers notice the plot armor (because let’s be honest, it’s there whether we like or not) or at least make it more realistic:

1) Injure your characters. Let it be known that no one is safe. During the heat of battle, the prized soldier loses his sword arm. The invincible superhero receives PTSD after witnessing a terrible event. Raise the stakes!

2) If they escape, make it believable. Did they sacrifice something to escape? Did a past experience give them the wits and knowledge to outsmart the danger? Justify your protagonist’s escape. Don’t make it an easy get away just because you need them out of the situation.

3) There are consequences. Every action sparks a reaction. Have there be realistic push back. Your character shouldn’t be immune to the rules and laws of your world.

4) Detailed Explanations. So, your character needs their limbs, their sanity and anything else you could strip them of. How do you make it seem like they’re not immune to everything then? Equip them with what they need (knowledge, weapon, confidence, etc) and really sell it to your reader on how they survived.

There’s no way a teenaged girl stakes a 400 year old vampire just by picking up a branch and defending herself. Equip her with some knowledge of vampires (fanfics to the rescue?), an ancient relic that she unknowingly wears around her neck and an insane amount of adrenaline… and maybe I’ll believe it.

5) Kill off other characters. Have their deaths affect the protagonist.

Instagram: coffeebeanwriting

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Stage Direction in Narration

“He walked into the room.” <> “She sat on the bench.” <> “They left the car.”

We all use stage direction. It’s unavoidable; readers need to know where our characters are in the space we’ve created for them. And sometimes a simple statement of movement is needed. But most of the time, it can be improved upon.

🙟🙝

If it wasn’t clear from the above examples, “stage direction” is when a character’s movement is narrated like one might write in a play or film script: straightforward and unembellished statements indicating a character’s direction.

This is great for scripts, where concise and clear instructions are preferable when a director and actor needs to follow them.

Not so great in a novel, where the author’s goal is to keep a reader’s interest and immersion. Let’s take a look at how you might improve these sentences by adding intent, context, or grounding description.

Afficher davantage

297 notes

·

View notes

Text

Character mannerisms to consider!

Mannerisms, in this case, are the little details that are unique to each character of your story! These are perfect ways help the reader know more about your character’s personality without needing to read through multiple sentences of description or dialogue. Mannerisms also become incredibly useful when you need to convey things like social status, upbringing, mental health status and how they interact with the world/people around them.

There are hundreds of unique ways to use mannerisms, for example linking one character to another despite their lack of interaction in the story. The dialogue and description might point to Character A having never met Character B, but they might share the same mannerisms, which would hint to some kind of past link between the pair.

How much space do they take up? Do they spread out when they sit or stay curled-up? Do they flail their arms to gesture? Do they speak loudly or quietly? Who listens when they speak up? Do they make a sound when they move?

How does your character sleep? What position? Do they sleep restlessly or soundly? Do they prefer covers, or do they sleep without?

How does your character greet people? Are they welcoming or reserved? How genuine are they being?

How much do they mirror others? Do they mirror everyone? (Mirroring is a subconscious behaviour where two+ people in a conversation will copy one another’s body language. This usually means there is a connection of some kind being made. Lack of / exaggerated mirroring might indicate towards a mental disorder or other (ex: personality disorder, neurodiversity, anxiety etc)

Which part of their body is the most expressive? Does your character use their hands a lot or do they tuck them away? Do they need movement to ground themselves (swaying, rocking, fidgetting…)?

Who would your character turn to in a group of people for comfort? Would they acknowledge that person more? Would they engage in a conversation with only them or would they just glance their way?

Do they have a re-occuring habit to indicate a mood? Do they crack their knuckles when excited? Do they bite their lip ring when angry? Do they look at their hands when sad?

How do they gesture? Do they speak with their hands? Do they point, nod or use their eyes to show something? Which movements are conscious, and which aren't?

Do they have a comfort item or person? Is there something they always think of? Is there something they hold with care? How much do they value that thing more than others?

How would they react to another person’s misfortune? Would their eyes light up? Would their heart hurt? How genuine would they feel? How genuine would they act?

Is there anything that makes them OOC (out of character)? (This is a good thing! One tiny OOC aspect can make a huge impact on that character) Perhaps they’re cruel but love cats? Perhaps they’re known for being the kindest but smile when they think of something tragic? How often do they act strangely? Do they do it in front of anyone? Do their actions indicate this or solely their thoughts?

I hope this helps you develop your characters! If you have anything to add, feel free to do so!

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

DESCRIBING THE PHYSICAL ATTRIBUTES OF CHARACTERS:

Body

descriptors; ample, athletic, barrel-chested, beefy, blocky, bony, brawny, buff, burly, chubby, chiseled, coltish, curvy, fat, fit, herculean, hulking, lanky, lean, long, long-legged, lush, medium build, muscular, narrow, overweight, plump, pot-bellied, pudgy, round, skeletal, skinny, slender, slim, stocky, strong, stout, strong, taut, toned, wide.

Eyebrows

descriptors; bushy, dark, faint, furry, long, plucked, raised, seductive, shaved, short, sleek, sparse, thin, unruly.

shape; arched, diagonal, peaked, round, s-shaped, straight.

Ears

shape; attached lobe, broad lobe, narrow, pointed, round, square, sticking-out.

Eyes

colour; albino, blue (azure, baby blue, caribbean blue, cobalt, ice blue, light blue, midnight, ocean blue, sky blue, steel blue, storm blue,) brown (amber, dark brown, chestnut, chocolate, ebony, gold, hazel, honey, light brown, mocha, pale gold, sable, sepia, teakwood, topaz, whiskey,) gray (concrete gray, marble, misty gray, raincloud, satin gray, smoky, sterling, sugar gray), green (aquamarine, emerald, evergreen, forest green, jade green, leaf green, olive, moss green, sea green, teal, vale).

descriptors; bedroom, bright, cat-like, dull, glittering, red-rimmed, sharp, small, squinty, sunken, sparkling, teary.

positioning/shape; almond, close-set, cross, deep-set, downturned, heavy-lidded, hooded, monolid, round, slanted, upturned, wide-set.

Face

descriptors; angular, cat-like, hallow, sculpted, sharp, wolfish.

shape; chubby, diamond, heart-shaped, long, narrow, oblong, oval, rectangle, round, square, thin, triangle.

Facial Hair

beard; chin curtain, classic, circle, ducktail, dutch, french fork, garibaldi, goatee, hipster, neckbeard, old dutch, spade, stubble, verdi, winter.

clean-shaven

Moustache; anchor, brush, english, fu manchu, handlebar, hooked, horseshoe, imperial, lampshade, mistletoe, pencil, toothbrush, walrus.

Sideburns; chin strap, mutton chops.

Hair

colour; blonde (ash blonde, golden blonde, beige, honey, platinum blonde, reddish blonde, strawberry-blonde, sunflower blonde,) brown (amber, butterscotch, caramel, champagne, cool brown, golden brown, chocolate, cinnamon, mahogany,) red (apricot, auburn, copper, ginger, titain-haired,), black (expresso, inky-black, jet black, raven, soft black) grey (charcoal gray, salt-and-pepper, silver, steel gray,), white (bleached, snow-white).

descriptors; bedhead, dull, dry, fine, full, layered, limp, messy, neat, oily, shaggy, shinny, slick, smooth, spiky, tangled, thick, thin, thinning, tousled, wispy, wild, windblown.

length; ankle length, bald, buzzed, collar length, ear length, floor length, hip length, mid-back length, neck length, shaved, shoulder length, waist length.

type; beach waves, bushy, curly, frizzy, natural, permed, puffy, ringlets, spiral, straight, thick, thin, wavy.

Hands; calloused, clammy, delicate, elegant, large, plump, rough, small, smooth, square, sturdy, strong.

Fingernails; acrylic, bitten, chipped, curved, claw-like, dirty, fake, grimy, long, manicured, painted, peeling, pointed, ragged, short, uneven.

Fingers; arthritic, cold, elegant, fat, greasy, knobby, slender, stubby.

Lips/Mouth

colour (lipstick); brown (caramel, coffee, nude, nutmeg,) pink (deep rose, fuchsia, magenta, pale peach, raspberry, rose, ) purple (black cherry, plum, violet, wine,) red (deep red, ruby.)

descriptors; chapped, cracked, dry, full, glossy, lush, narrow, pierced, scabby, small, soft, split, swollen, thin, uneven, wide, wrinkled.

shape; bottom-heavy, bow-turned, cupid’s bow, downturned, oval, pouty, rosebud, sharp, top-heavy.

Nose

descriptors; broad, broken, crooked, dainty, droopy, hooked, long, narrow, pointed, raised, round, short, strong, stubby, thin, turned-up, wide.

shape; button, flared, grecian, hawk, roman.

Skin

descriptors; blemished, bruised, chalky, clear, dewy, dimpled, dirty, dry, flaky, flawless, freckled, glowing, hairy, itchy, lined, oily, pimply, rashy, rough, sagging, satiny, scarred, scratched, smooth, splotchy, spotted, tattooed, uneven, wrinkly.

complexion; black, bronzed, brown, dark, fair, ivory, light, medium, olive, pale, peach, porcelain, rosy, tan, white.

20K notes

·

View notes

Text

the transition from people needing each other to wanting each other is literally one of my greatest weaknesses that shit makes me want to walk into the sea and sit on the ocean floor for a thousand years

37K notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's Talk About: Minor Character Development

“Creating one interesting character is hard enough — but when it comes to writing a whole novel or series of books, you have to create dozens of them. How can you keep your supporting cast from seeming like cookie-cutter people? There’s no easy answer, but a few tricks might help you create minor characters who don’t feel too minor.” [x]

10 Secrets to Creating Unforgettable Supporting Characters

Give them at lease one defining characteristic. "…lots of people have one or two habits that you notice the first time you meet them, that stand out in your mind even after you learn more about them.“

Give them an origin story. ”…Your main character doesn’t necessarily need an origin story, because you’ve got the whole book to explain who he/she is and what he/she is about. But a supporting character? You get a paragraph or five, to explain the formative experience that made her become the person she is, and possibly how she got whatever skills or powers she possesses.“

Make sure they talk in a distinctive fashion. ”…you still have to make sure your characters don’t all talk the same. Some of them talk in nothing but short sentences, others in nothing but long, rolling statements full of subordinate clauses and random digressions. Or you might have a character who always follows one long sentence with three short ones.“ ”…One dirty shortcut is to hear the voice of a particular actor or famous person in your head, as one character talks.“

Avoid making them paragons of virtue, or authorial stand-ins. ”…People who have no flaws are automatically boring, and thus forgettable.“ ”…Any character who has foibles, or bad habits, or destructive urges, will always stand out more than one who is pure and wonderful in all ways. And nobody will believe that you’ve chosen to identify yourself, as the author, with someone who’s so messed up. (Because of course, you are a perfect human being, with no flaws of your own.)“

Anchor them to a particular place. ”…A huge part of making a supporting character “pop” is placing her somewhere. Give her a haunt — some place she hangs out a lot. A tavern, a bar, an engine room, a barracks, a dog track, wherever. It works both ways — by anchoring a character in a particular location, you make both the character and the location feel more real.“

Introduce them twice — the first time in the background, the second in the foreground. ”…You mention a character in passing: “And Crazy Harriet was there too, chewing on her catweed like always.” And you say more about them. And then later, the next time we see that character, you give more information or detail, like where she scores her catweed from. The reader will barely remember that you mentioned the character the first time — but it’s in the back of the reader’s mind, and there’s a little “ping” of identification.“

Focus on what they mean to your protagonists ”…What does this minor character mean to your hero? What role does he fulfill? What does your hero want or need from Randolph the Grifter? If you know what your hero finds memorable about Randolph, then you’re a long ways towards finding what your readers will remember, too.“

Give them an arc — or the illusion of one. ”… You can create the appearance of an arc by establishing that a character feels a particular way — and then, a couple hundred pages later, you mention that now the character feels a different way.“ ”…A minor character who changes in some way is automatically more interesting than one who remains constant…“

The more minor the character, the more caricature-like they may have to be. ”…This one is debatable — you may be a deft enough author that you can create a hundred characters, all of whom are fully fleshed out, well-rounded human beings with full inner lives.“ ”…some writing styles simply can’t support or abide cartoony minor characters. But for your third ensign, who appears for a grand total of two pages, on page 147 and page 398, you may have to go for cartoony if you want him to live in the reader’s mind as anything other than a piece of scenery.“

Decide which supporting characters you’ll allow to be forgettable after all. ”…And this is probably inevitable. You only have so much energy, and your readers only have so much mental space. Plus, if 100 supporting characters are all vivid and colorful and people your readers want to go bowling with, then your story runs the risk of seeming overwritten and garish.Sometimes you need to resign yourself to the notion that some characters are going to be extras, or that they’re literally going to fulfill a plot function without having any personality to speak of. It’s a major sacrifice they’re making, subsuming their personality for the sake of the major players’ glory.“

Keep reading

21K notes

·

View notes

Text

—you care for me. I feel it like an ax in my chest.

Cynthia Bond, from 'Ruby'

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

A summary of how people die (and don't) in swordfights

This is a really good article about how quickly people actually die from cuts and punctures inflicted by swords and knives. However, it’s really really long and I figured that since I was summarizing for my own benefit I’d share it for anyone else who is writing fiction that involves hacking and slashing your villain(s) to death. If you want the nitty gritty of the hows and whys of this, you can find it at the original source.

…even in the case of mortal wounds, pain may not reach levels of magnitude sufficient to incapacitate a determined swordsman.

Causes of death from stabs and cuts:

massive bleeding (exsanguination) - most common

air in the bloodstream (air embolism)

suffocation (asphyxia)

air in the chest cavity (pneumothorax)

infection

Stabbing vs cutting:

Stabbing someone actually takes very little force if you don’t hit bone or hard cartilage.

The most important factor in the ease of stabbing is the velocity of the blade at impact with the skin, followed by the sharpness of the blade.

Stabbing wounds tend to close after the weapon is withdrawn.

Stabbing wounds to muscles are not typically very damaging. Damage increases with the width of the blade.

Cutting wounds are typically deepest at the site of initial impact and get shallower as force is transferred from the initial swing to pushing and pressing.

Cutting wounds have a huge number of factors that dictate how deep they are and how easily they damage someone: skill, radial velocity, mass of the blade, and the size of the initial impact.

Cutting wounds along the grain of musculature are not typically very damaging but cutting wounds across the grain can incapacitate.

Arteries vs veins:

Severed veins have almost zero blood pressure and sometimes even negative pressure. They do not spurt but major veins can suck air in causing an air embolism.

Cutting or puncturing a vein is usually not fatal.

Severed arteries have high blood pressure. The larger arteries do spurt and can often cause death due to exsanguination.

Body parts as targets:

Severing a jugular vein in the neck causes an air embolism and will make the victim collapse after one or two gasps for air.

Severing a carotid artery in the neck cuts off the blood supply to the brain but the victim may be conscious for up to thirty seconds.

Stabbing or cutting the neck also causes the victim to aspirate blood that causes asphyxiation and death.

Severing a major abdominal artery or vein would cause immediate collapse, but this takes a fairly heavy blade and a significant amount of effort because they are situated near the spine.

Abdominal wounds that only impact the organs can cause death but they do not immediately incapacitate.

Severing an artery in the interior of the upper arm causes exsanguination and death but does not immediately incapacitate.

Severing an artery in the palm side of the forearm causes exsanguination and death but does not immediately incapacitate.

Severing the femoral artery at a point just above and behind the knee is the best location. Higher up the leg it is too well protected to easily hit. This disables and will eventually kill the victim but does not immediately incapacitate.

Cutting across the muscles of the forearm can immediately end the opponent’s ability to hold their weapon.

Cutting across the palm side of the wrist causes immediate loss of ability to hold a weapon.

Stab wounds to the arm do not significantly impact the ability to wield a weapon or use it.

Cuts and stab wounds to the front and back of the legs generally do not do enough muscle damage to cause total loss of use of that leg.

Bone anywhere in the body can bend or otherwise disfigure a blade.

The brain can be stabbed fairly easily through the eyes, the temples, and the sinuses.

Stabs to the brain are more often not incapacitating.

The lungs as targets:

Slicing into the lung stops that lung from functioning, but the other lung continues to function normally. This also requires either luck to get between the ribs or a great deal of force to penetrate the ribs.

Stabbing the lung stops that lung from functioning, but the other lung continues to function normally. It is significantly easier to stab between ribs than to slice.

It is possible to stab the victim from the side and pass through both lungs with an adequate length blade. It is very unlikely that this will happen with a slicing hit.

“Death caused solely by pneumothorax is generally a slow process, occurring as much as several hours after the wound is inflicted.”

Lung punctures also typically involve the lung filling with blood, but this is a slow process.

The heart as a target:

I’m just going to quote this paragraph outright with a few omissions and formatting changes for clarity because it’s chock-full of good info:

…[stabbing] wounds to the heart the location, depth of penetration, blade width, and the presence or absence of cutting edges are important factors influencing a wounded duelist’s ability to continue a combat.

Large cuts that transect the heart may be expected to result in swift incapacitation…

…stab wounds, similar to those that might be inflicted by a thrust with a sword with a narrow, pointed blade may leave a mortally wounded victim capable of surprisingly athletic endeavors.

Essentially, the heart can temporarily seal itself well enough to keep pressure up for a little while if it’s a simple stab. The arteries around the heart, while they are smaller and harder to hit, actually cause incapacitation much more quickly.

47K notes

·

View notes

Text

I love you angry characters I love you revenge arcs I love you protagonists who kill people and don’t feel bad about it I love you manipulative heroes I love you gray morals I love you terrifying protagonists I love you characters who hold boiling grudges I love you characters who reveal that their perceived harmlessness was just patience the whole time I love you stories about atonement and rage and vengeance that don’t end in forgiveness or guilt I love you stories that explore the healing power of incandescent rage

45K notes

·

View notes