Photo

Embroidery Hoop Art and Patterns

Emillie Ferris on Etsy

22K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Oh, the indignity of being flipped so that your pasty belly can be used as a species identification reference! This Great Plains toad [Anaxyrus cognatus] was found and photographed by serial toad flipper Gary Nafis in Cochise County, Arizona.

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

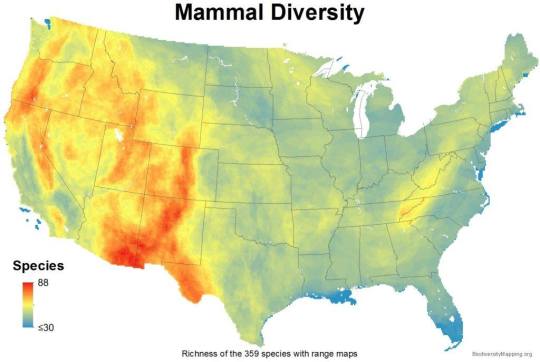

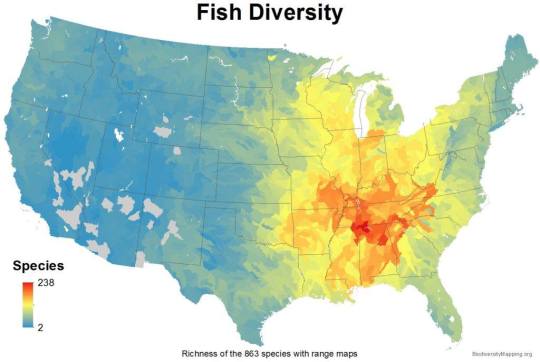

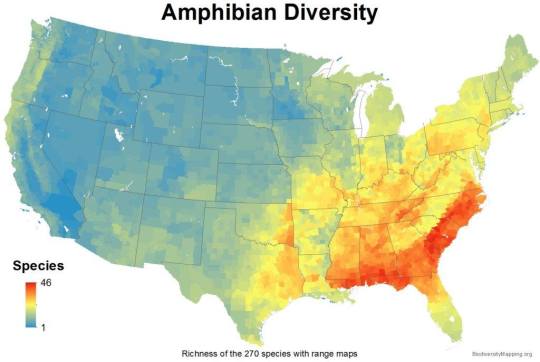

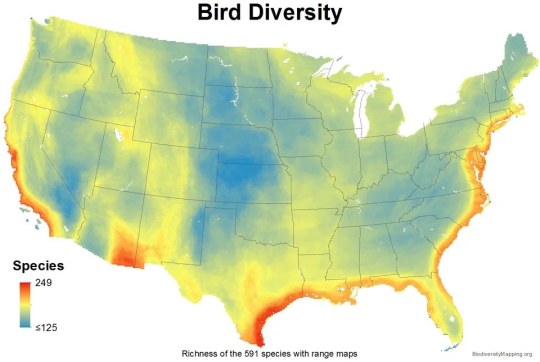

Diversity Maps of vertebrate groups in the United Statest

Find out how these maps were generated here:

https://biodiversitymapping.org/wordpress/index.php/home/

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

Two New Asian Giant Hornet Sightings in Pacific Northwest

https://sciencespies.com/news/two-new-asian-giant-hornet-sightings-in-pacific-northwest/

Two New Asian Giant Hornet Sightings in Pacific Northwest

In early May, news of a super-sized insect invader with a taste for honey bees drew widespread attention. The Asian giant hornet of Japan and Southeast Asia—dubbed the “murder hornet” by at least one Japanese researcher, perhaps owing to a foible of translation—was seen in North America for the first time in 2019. The four sightings prompted scientists in the United States and Canada to set traps in hopes of finding and eradicating the invasive species before it could establish a foothold in North America.

Now, two new confirmed sightings of individual Asian giant hornets—one in Washington State and one in British Columbia—have expanded the area being patrolled by researchers, reports Mike Baker of the New York Times.

The hornet fails to fit the legal definition of murder but fairly earns the title of “giant.” With queens up to two inches long, the species is the world’s largest hornet. Just a few of these enormous buzzing insects can slaughter an entire hive of honeybees in a matter of hours, decapitating thousands of adult bees, whose stingers can’t pierce the hornets’ armor.

It’s this appetite for apian destruction that worries officials at the WSDA. “If it becomes established, this hornet will have negative impacts on the environment, economy, and public health of Washington State,” the agency writes.

A photo of the dead Asian giant hornet spotted near the town of Custer in Washington State in late May.

(WSDA / Joel Nielsen)

One of the new sightings occurred earlier this week when a resident spotted a large dead insect on the side of the road in Custer, Washington, according to a statement from the Washington State Department of Agriculture (WSDA). State and federal labs confirmed the specimen’s identity, but the statement notes it was encountered within the area already being monitored by local officials hoping to find and destroy any nesting colonies.

But earlier this month, a woman in Langley, British Columbia, killed a strange insect she encountered near her home by crushing it with her foot, reports local broadcast station KING 5 NBC. The corpse was collected by local officials and confirmed to be an Asian giant hornet, Paul van Westendorp, a provincial apiculturist for British Columbia, tells the Times.

Langley is eight miles north of last year’s pair of U.S. sightings near Blaine, Washington, suggesting the invaders may have spread farther than scientists anticipated.

“This particular insect has acquired a larger distribution area at this time than we had thought,” Van Westendorp tells the Times. In a letter Van Westendorp sent to local beekeepers that was posted to Facebook by apiculturist Laura Delisle, he writes that the specimen will be necropsied to determine if it was a queen or a worker and that “it is expected that more sightings will be reported in the coming months.” He further calls on beekeepers “to be vigilant and report any unusual activities and sightings.”

However, even in light of the expanded search area in Canada, Osama El-Lissy, an official with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Plant Protection and Quarantine Program says “at this time, there is no evidence that Asian giant hornets are established in Washington State or anywhere else in the United States.”

If a population of Asian giant hornets established itself in the U.S. it would pose a threat to honey bees, but the risks to public health may be more debatable. As Floyd Shockley, the entomology collections manager at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History pointed out when news of the hornet’s arrival first circulated, “more people die of honey bee stings in the U.S. than die annually, globally, from these hornets. About 60 to 80 people die from [allergic] reactions to honey bee stings [in the U.S.]; only about 40 people die per year, in Asia, mostly in Japan, from reactions to the [giant hornet] stings.”

The WSDA site notes the Asian giant hornet isn’t particularly aggressive towards humans or pets but will attack if threatened, with each hornet being capable of delivering multiple, potent stings. Douglas Main of National Geographic reports that though the venom of a honeybee is more toxic, giant hornets can inject roughly 10-times more venom.

It would take “a couple hundred” giant hornet stings to kill a human, compared to roughly 1,000 honeybee stings, Justin Schmidt, an entomologist who studies insect venom and is responsible for the eponymous Schmidt Pain Index, tells National Geographic.

Van Westendorp tells the Times most people shouldn’t worry about the giant hornets (unless they’re allergic) and worries undue hysteria could result in people harming their local environment by killing bees and wasps they’ve misidentified as Vespa mandarinia (the hornet’s scientific name). Jennifer King of KING 5 reports several fake signs purporting to warn hikers of nesting giant hornets in the area were removed from trailheads in Washington over Memorial Day Weekend.

#News

62 notes

·

View notes

Link

When early tetrapods transitioned from water to land the way they breathed air underwent an evolutionary revolution. Fish use muscles in their head to pump water over their gills. The first land animals utilized a similar technique—modern frogs still use their head and throat to force air into their lungs. Then another major transformation in vertebrate evolution took place that shifted breathing from the head to the torso. In reptiles and mammals, the ribs expand to create a space in the chest that draws in breath. But what caused the shift?

A new study published on May 12 in Scientific Reports posits a new hypothesis—the intermediate step was driven by locomotion.

When lizards walk, they bend side-to-side in a sprawling gait. The ribs and vertebrae are crucial to this movement, but it was unclear how until now. Researchers captured the 3-D motion of lizard ribs and vertebrae using XROMM, a combination of CT scans and X-ray videos. They recorded three savannah monitor lizards and three Argentine black and white tegus walking slowly on a treadmill. The resulting images revealed that while the spine is bending, every rib in both species rotated substantially around its vertebral joint, twisting forward on one side of the body and backward on the other side alternatively with each stride. The mechanics follow nearly the same pattern as when the reptiles inhale and exhale.

“It’s really exciting because we didn’t previously have plausible hypotheses for how rib-breathing evolved,” said first author Robert Cieri, a postdoc at the University of the Sunshine Coast and who conducted the research while at the University of Utah, where he is still affiliated. “We’re proposing that these rib movements first started to facilitate locomotion, then were co-opted for breathing.”

Continue Reading.

252 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Blue jay … Delaware backyard … 5/21/20 the most still and photogenic blue jay i’ve ever seen tbh

548 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tiny mushrooms growing on a Douglas fir pine cone.

59K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Right, you in the white coat, get to work on curing this disease.”

“But I’m not a virologist, I work with animals and study their behaviour.”

“Just do science.”

“But my degree is in——“

“Do. Science.”

30K notes

·

View notes

Text

Deer and cherry blossoms in Nara park, Japan

(via)

199K notes

·

View notes

Link

hell yes baybee!!!! finally, some good fucking population genetics

also i C A N N O T believe that this is real:

4K notes

·

View notes

Photo

The ocean sunfish (Mola mola) is one of the heaviest known bony fishes in the world, with adults typically weighing between 247 and 1,000 kg (545–2,205 lb).

This incredible illustration depicts the skeleton of a 3-foot-6-inch specimen, found dead at the beach in Vejlefjord (Denmark) on 2 November 1878.

Illustration from “Spolia Atlantica” (1898) by Johannes Japetus Sm. Steenstrup and Christian Frederik Lütken.

Explore the work in BHL thanks to Smithsonian Libraries

https://s.si.edu/3bOqRrO

517 notes

·

View notes