Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Rogerian Argument: What Is It & How Do I Write One? 3/

Here is a quote from the Kirszner & Mandell textbook I mentioned in the previous post:

“Rogerian argument begins with the assumption that people of good will can find solutions to problems that they have in common. Rogers recommends that you consider those with whom you disagree as colleagues, not opponents. Instead of entering into the adversarial relationship that is assumed in classical argument, Rogerian argument encourages you to enter into a cooperative relationship in which both you and your readers search for common ground––points of agreement about a problem. By taking this approach, you are more likely to find a solution that will satisfy everyone” (Kirszner and Mandell 192).

This quote makes a good jumping-off place for us to examine how “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” works as an example of Rogerian argument.

Sidenote: To be clear, there is really no evidence that Dr. King was deliberately setting out to craft his letter as an explicitly Rogerian argument –– King and Rogers lived and worked through roughly similar time periods, but Rogers’ work on argument would have been still in progress at the time when King was writing. This is part of what I meant in the first post when I pointed out that even if Rogers popularized and “formularized” this style of argument, he didn’t invent trying to get along.

One of the nice things about the quote from Kirszner & Mandell I gave you above is that it breaks Rogerian argument down into a clearly-identifiable set of components that, when put into operation together, lead to the type of argument we are talking about here. If we turn that set of components into a bullet list (I love bullet lists), we get something like this:

- sets up the expectation of sincerity & goodwill

- addresses his readers as colleagues, instead of opponents

- presents the problem he is writing about as a shared problem

- establishes common ground with his readers

- invites his readers to participate with him in finding “a solution that will satisfy everyone” (Kirszner and Mandell 192)

But don’t take my word for it!

Go through King’s essay (linked in post #2), and find at least one quote for each of the items on that bullet list. Then go to the discussion post in this week’s Canvas module and submit your answers!

We aren’t done with Rogerian argument yet –– not by a long shot –– so stay tuned for more!

0 notes

Text

Rogerian Argument: What Is It & How Do I Write One? 2/

For a year or two, I taught EN 112 using a textbook that actually had an entire section devoted to Rogerian and other forms of argument that seek common ground and compromise rather than aiming to “win” a debate. I can’t make hanging indents on Tumblr (sad times!), but here is the general citation info in case anybody wants to look up that book:

Kirszner, Laurie and Stephen Mandell. Practical Argument: A Text and Anthology. 4th edition, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2020.

^ obviously the 4th edition was only the most recent one we used; in 2018 and 2019 we used the 3rd edition, but not much changed (I’m actually not even sure why they issued a new edition tbh).

Anyway, when we switched to the St. Martin’s Guide this Fall, I kept Rogerian argument in my syllabus because it had proven to be one of the more useful structures for students to learn and employ outside the classroom: Rogerian argument has a lot of practical applications that have nothing to do with writing an essay for your English class.

It’s the last of our expository essays for the semester, and I think it makes a good way to end the semester on a practical note that, as I said in the video I posted to Canvas yesterday, should set you off on a journey of mature and reasoned engagement with other people’s ideas that will continue well past your college career and hopefully carry over into many other aspects of your lives.

“Letter from a Birmingham Jail” - good example!

If you have been paying close attention to our scheduled readings, you will be aware that we just read Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” (and if you have not been paying close attention, then now is an excellent opportunity to correct that and go read his essay, because you will most definitely need to be familiar with it for the next few assignments!).

Here’s a brief overview, from a post I wrote for my EN 112 students back during lockdowns this Spring:

Originally written by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in –– as the title suggests –– a jail in Birmingham, AL, “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” is one of King’s most enduring and influential pieces of writing. It is also one of the very few intended to be read –– not listened to –– by its immediate audience.

A friend of mine, who is old enough to remember listening to Dr. King’s televised speeches as a child, tells me that there is no comparison between reading Dr. King’s work and hearing him speak live. (I like to remind him that no comparison would be useful, since unless my friend wants to invent a time machine and give me a trip I will never have the chance to make such a comparison for myself.)

Perhaps because it is not intended as a speech, “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” makes extensive use of intertextuality, particularly in King’s deployment of Biblical imagery and references to early church history –– not just to support his argument, but to emotionally connect with his audience. When we read discuss King’s essay (beginning Wednesday 4/15), we will pay particular attention to how King tailors his use of “prior texts” (I’m citing my own dissertation here; can you tell I’m enormously proud? :D) to his audience.

One important note that may help you as you begin to work your way through King’s text: In “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” –– as in many other Rogerian essays –– King actually knows exactly who his audience is, and can address his readers directly: he doesn’t have to guess or imagine. This makes a difference to the essay’s style and tone, as you may imagine!

Knowing one’s audience is often key to a strong Rogerian essay –– it’s a challenge to establish common ground with people about whom you know nothing –– but you don’t have to be on intimate terms with the members of your target audience to make some educated guesses about their likely concerns and the perspective from which they are entering the conversation.

0 notes

Text

Rogerian Argument: What Is It & How Do I Write One? 1/

“Rogerian” argument is named after the psychologist Carl Rogers; he didn’t invent this style of argument (attempting to find compromise solutions to shared problems isn’t exactly a new idea), but he did popularize it over the course of his career (you have a link in Canvas to an overview of Rogers’ life and work, if you want to know more).

Carl Rogers is probably most widely-recognized today for his development and advocacy of “person-centered” therapy ... but we are here for the approach to argument he urged his patients (and others) to use.

To get a good basic understanding of what Rogerian argument looks like (and how it differs from what we’ve been doing all semester, which in formal terms is known as “Aristotelian” argument), please click on the following links and read through the materials you’ll find on the other side of them (both sets of info are short, I promise!):

From “The Owl” at Purdue

From Colorado State Writing Guides

0 notes

Photo

If you are in either of my EN 112 courses this Fall (2020), you can ignore that last paragraph with the page numbers (old textbook; outdated page numbers). I feel as if I have somehow reached a major MILESTONE in my professorial career: I now have actual “lecture notes” (well, okay, Tumblr posts) that I can re-use. Some of them I probably won’t use ever again, because I always think “ooooh that’s a shiny new way to do the thing!!!!!” ... but as far as proposal essays go, the basic structure has not changed much in the past thousand years (and it isn’t likely to in the immediate future). Some things are “classics” for a reason, and a no-frills, back-to-basics proposal argument is one of those things.

There is nothing particularly complicated about a proposal essay –– but they do tend to require a lot of detailed pre-planning, by which I mean: You can’t propose a solution effectively unless you know it inside and out. When people struggle with the proposal essays, it’s almost always because they don’t have the details nailed down: they haven’t figured out who should do what and why.

So: that’s the challenge for today! Figure out a problem that’s related to your topic somehow, and identify a way to solve it that could reasonably work. Then figure out how to make that solution work, in practical terms: Who do you call? What do you tell them? What kind of funding will the project need? Whose permission/cooperation is essential to success?

If you can answer those questions - in substantial detail, with hard numbers and real names - then you are well on your way to a good proposal essay!

Very rarely, a proposal argument will actually start by describing (and debunking) an alternative proposal; you see this a lot in political debates and campaign “stump” speeches: Candidate X starts out by saying “My Opponent wants to blah, blah, blah. Well, I say bleep bloop! Here’s a better way to fix yadda yadda …”

EVERY NOW AND THEN, a student will get stumped (hey, it happens!) and ask me:

The best answer I have for this is: Then stop arguing for it.

The world is too full of good ideas — and so are you — for you to be arguing in favor of bad ones. If you have to struggle to come up with some reason why the solution you are proposing is any better than the solutions already out there, then you probably need to improve your proposal.

The “Problem-Solving Strategies” chart in your textbook (page 565 if you are using the 4th edition) is a good place to start on that — and a good place to return to whenever you get stuck.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Hopefully you can see why these requirements might lend themselves to one particular organizational strategy. If a proposal argument has to identify a problem and propose a solution, it makes sense that in most cases you would need to tell readers what the problem is before explaining how you intend to fix it. By the same logic, readers aren’t likely to care much about how you intend to fix whatever the problem is unless they’re already convinced that:

a) the problem is real (it exists, and it’s a problem)

and

b) they should care (often but not always because it affects them directly/indirectly)

On the other end of things, nobody is going to buy into your proposal unless they can see that:

a) sure, we can do the thing

and

b) doing the thing will fix the problem

FOR ALL OF THESE REASONS, the components in a proposal argument tend to be organized pretty much the same way they are in the graphic I just gave you. There are always exceptions — but when in doubt, it’s hard to go wrong with organizing your essay according to the basic logic of “What will my reader already need to know/be convinced of in order to understand the point I’m about to make?”

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

If you have made your way through the annotated bibliography,

by this point you should have a pretty good idea of what the core concepts and major debates are in your field. Most of you at this point could probably draft a pretty good essay that summed up the “background knowledge” readers would need to understand your topic ... if you were already sure what that topic was.

I am not referring here to whether or not you understand your own research project; I mean, most of us, most of the time, are to some extent always discovering our projects as we go, but I think most of you have a pretty good handle on where your research essays are headed. However, if I say, “Write a 10-paragraph essay providing background on your topic and identifying your sources,” then what you come up with is going to depend largely on how you interpret the phrase “on your topic.”

For example:

LaCorrey is writing about trips to Disney (sort of; it’s more complicated than that, because it always is!), and arguing that a trip to Disney is not simply a vacation, but an opportunity for experience and experimentation with identity and playfulness and escape in an environment that encourages visitors to leave the “real world” at the gates. So “background information” for that topic might mean “a history of Disneyworld” ... but that probably would not actually help readers to understand where the research essay’s thesis was coming from. Or it might mean “the psychology of cosplay,” which maybe gets us closer, but is still too narrow. Or it might mean “explaining festivals,” which is probably pretty close, but how close is going to depend on the direction LaCorrey ultimately decides to go, and what is important to their topic.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Information Synthesis 2/3

In other words:

A big part of the challenge for you in crafting your information synthesis essays is to figure out what readers will really need to know in order to understand where your thesis in the research essay is coming from. I like to think of this as providing your reader with a context in which to interpret the claim you are about to make. Context matters in communication: for example, “stand by” can mean either “do nothing and let a disaster unfold before your eyes” OR “hold up and wait for further instructions” –– and usually the only way we know which meaning applies is from the context in which we hear the expression. In a military setting, “stand by” means stay right where you are and be prepared to act at a moment’s notice; if we are talking about being witnesses to a crime, then “stand by” means just watching while that nice old lady gets mugged.

To be clear, it is possible to conduct information synthesis in a way that is not designed to provide context: sometimes students tell me that they have written research essays in high school, and a lot of these (based on student descriptions, anyway!) are basically extended exercises in information synthesis –– finding stuff out, explaining the big ideas, giving credit to the relevant sources. There is nothing wrong with any of that. In the “real world,” however –– and in most academic contexts (I’ll let you decide whether or not that’s the same thing lol) –– synthesizing a bunch of information and organizing it into an essay for no reason at all, or “just because,” is pretty darn rare. Most of the time, if we are synthesizing information, it’s because somebody has asked us to explain something and we are trying to provide the information they need, or it’s because we are about to try and explain our position on something and we recognize that our interlocutor (fancy linguistic term for the person we’re talking to/with) is going to need to know some other stuff in order to get where we’re coming from a couple of minutes down the road.

For this reason, as far as this essay assignment goes I want you to think about what I am asking you to do in terms of

information as context

–– for your readers, mainly, but also for yourself, in the sense that drafting an information synthesis is a great way to help reorient yourself with respect to your developing research project.

0 notes

Text

Information Synthesis 3/3

I already told you that from the definition essay on, you would have the option for each expository essay to develop material related to your research project OR to complete your essay assignment by responding to a general prompt.

If you are sick of your research project for this week and you just want to write about something else for a change, your general prompt is this:

Using at least five scholarly (peer-reviewed) journal articles to source your information, draft an information synthesis essay that provides readers with the context they need to understand why the Broadway musical Hamilton was a hit.

You might consider explaining the history of musical theater and its social impact; you might explain the relationship between “show tunes” and popular music; you might seek to help readers understand why a hip-hop retelling of Alexander Hamilton’s biography performed by an Black and Brown cast struck a chord with audiences beyond the catchiness of the songs performed. These aren’t your only options for this particular synthesis; they are just some of the ones I can think of “off the top of my head.” What I want you to realize is that any of these –– and probably several others –– could form the “topic” for a perfectly reasonable information synthesis essay. The set of information you choose to synthesize depends on how you understand –– and how you want your readers to understand –– the overwhelming popular success Hamilton has enjoyed.

If you want to write your information synthesis on the same topic as your research project, you will be doing the same work: it just won’t be on Hamilton.

Think in terms of the broad related areas of knowledge that “feed into” a good understanding of your topic: What will readers need to know in order to understand the question your thesis statement answers, or the problem it seeks to solve? PROBABLY A LOT OF THINGS, but your information synthesis essay cannot cover all of those areas: in order to stay on topic, your essay has to cover just one area; in order to function as an effective essay, it has to identify the core concepts in that area and explain them thoroughly.

I said we were going to be using your actual projects as the basis for our examples in this second half of the semester, so here are some ideas:

Kinley is writing on the need to integrate speech therapy in PreK for ALL students. So her information synthesis might provide some background on what speech therapy is, how the need for it is currently being identified, and what the existing standards for implementation are. OR, since she is thinking in terms of PreK and that obviously involves schools, her information synthesis might focus on who determines what we include in PreK education, and how. OR it might focus on teacher preparation, to explain where and how speech therapy might fit in terms of who is providing it in the classroom. OR Kinley might read a bunch of sources on how PreK is funded and synthesize the basics in order to prepare readers to understand her plan for funding speech therapy integration.

Emma is writing about the psychological effects on college-level athletes of steroid use/abuse in MLB. Her information synthesis might give an overview of the history of steroid drug development and how steroids are used and abused. OR she might focus on the psychological pressures facing college-level athletes in order to help readers understand why athletes might be susceptible to getting “psyched out” by just the expectation of steroid abuse at the professional level. OR she might draft an information synthesis that explained how steroid use entered sports in the first place, and how it has been handled by various sports associations over the past several decades.

What I want you to notice is that any of those approaches (and probably some others) could work very well for this assignment. The way your individual information synthesis shapes up is going to depend on the approach you want to take and what you think readers will need to know in order to understand your thesis statement and your eventual argument in the research essay.

Realistically, your research essay is going to end up containing a lot of short bursts of information synthesis explaining concepts as they come up; the information synthesis essay, on the other hand, asks you to pick just one key concept and stick with it for several paragraphs.

Your information synthesis essay, therefore, should:

identify a core concept or area of background knowledge related to your research topic

draw on at least five peer-reviewed sources to develop an understanding of that concept/area

explain the concept or the background information for your readers, clearly and concisely, in such a way that they will be positioned to understand a key element of your (eventual) argument going forward

consist of roughly 350-500 words to thoroughly develop and explain the ideas you are discussing

NOT include your own perspective/opinion

clearly signal attribution and carefully cite each source so that readers can easily follow up on your citations in order to conduct their own research

You are free to go ahead and begin drafting the information synthesis essay whenever you would like (it is due Tuesday, Oct. 20th, at 11:59pm), but all I am asking you to do for today is to return to Canvas and complete the instructions to “brainstorm” your information synthesis and, before Monday, give your classmates feedback on their brainstorming posts.

Got it? Good! Let’s get started. :)

0 notes

Note

Outright lost.

Okay ... on what? Let’s take a look at what you are struggling with!

0 notes

Text

Library Research Tips & Tricks: Part 5/5

Part One

Part Two

Part Three

Part Four

Just to be clear, the little checkbox on the library’s sidebar is not the only way to find out if a particular journal uses the peer review process; it’s just the fastest and easiest way. Also, regrettably, that checkbox ONLY makes sure the articles that show up in your search results are peer-reviewed; it does NOT mean that all of the articles you see will be useful.

On the other hand, some topics are a lot more likely to show up in peer-reviewed journals than others, and sometimes that can help you out.

Here is an example search without the peer-review filter, and then that same search again with the filter applied:

NEXT TIME, we will talk about how to use these multiple search boxes and their different “Boolean” operators to refine your search results:

For now, though, I want you to just “play around” with this interface using your own research topic and whatever search terms come to mind.

Click the “Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals” checkbox and open several of the results under different searches. Get used to the layout of journal articles and the way they introduce their topics, both of which are probably different from most of the materials you are used to reading. If you attended one of this week’s in-class workshops, you heard me talk a little bit about academic “genres” and how they help to establish a set of implicit expectations for the kind of information we’ll see and the way it will be presented; the best way to become familiar with any genre is to see/watch/hear/read a lot of examples of it, so one of those goals of this module is to just increase your familiarity with some of the basic genres in journal article publishing.

Another goal is to actually find sources you might use for your research essays, so after you’ve tinkered around with searches for a while, I want you to do TWO THINGS:

Go back to the research topic proposal assignment and resubmit based on the conversations we’ve had, the feedback you’ve received, and the thinking you’ve done since you submitted the first version.

Under the Discussion post in today’s Canvas module, post at least two screenshots of your search results pages (drag and drop to place them “inline” - don’t add them as attachments), and ALSO provide the MLA style citation for at least two articles you found during your search that you think you might use in your annotated bibliography.

That’s it for today - but we will have more library research guided work next week, so stay tuned!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Library Research Tips & Tricks: Part 4/?

Part One

Part Two

Part Three

Important Explanation Alert: WTF are “peer-reviewed” articles, and why do I need them??????

There is a whole long explanation about how academic publishing works that is not interesting even if you want to/have to participate in academic publishing yourself. I’ll give you the (very) short version, because the structure of academic publishing does impact your own research in two key ways.

Basically, in academia, if you want to publish an article (and you definitely do; the saying for academic careers is “publish or perish”), you send it off to a journal for consideration. The most prestigious journals have both an editorial staff and external “peer reviewers.” These peer reviewers are experts in their fields, and when a journal receives an article submission that the editorial staff think might be worth publishing, an editor identifies at least two people who are experts on the same topic the article is dealing with, and they take the name off the article (so that the reviewers won’t know whose work they are reading and be influenced by personal considerations - academic fields are small enough that you actually can know a lot of the people in them) and send it to those two people for a review.

The reviewers send back the article submission with their comments and recommendations, which are usually “accept without revisions” (meaning go ahead and publish it as-is, which is rare); “accept with minor revisions” (more common); “accept with major revisions” (pretty common); “do not accept” (happens more than any of us would like tbh).

Assuming the peer reviewers both recommend one of those first three options, the article then gets revised (sometimes more than once) and eventually published when two peer reviews reach a consensus that it’s good to go and worth sharing.

I said the peer review process was important for your own research in “two key ways,” so here they are:

Getting an article through the peer review process and into publication takes a while; depending on the field and the speed of the reviewers, anywhere from six weeks (VERY fast; medical fields conducting research with urgent health consequences are basically the only places where I’ve seen this); to close to two years (that’s at the far end of the spectrum). Mostly you’re looking at something like 9-18 months from draft submission to publication. This is relevant information for you to have if your topic is time-sensitive (this will be true, for example, for those of you writing on digital technologies or social conditions related to the ongoing pandemic). Knowing the approximate “lag time” you can expect to find in journal articles can help you to narrow down your search parameters by date.

Peer review, when it works, acts as a form of quality control. It doesn’t mean that nothing stupid or inaccurate or just plain off the wall EVER gets published ... but it helps to make sure that those articles, in any given field and in any scholarly journal, are pretty rare. That means you and your reader can share a higher degree of confidence in the information and analysis found in peer-reviewed journal articles than in other sources that don’t go through that same process.

0 notes

Text

Library Research Tips & Tricks: Part 3/?

Part One

Part Two

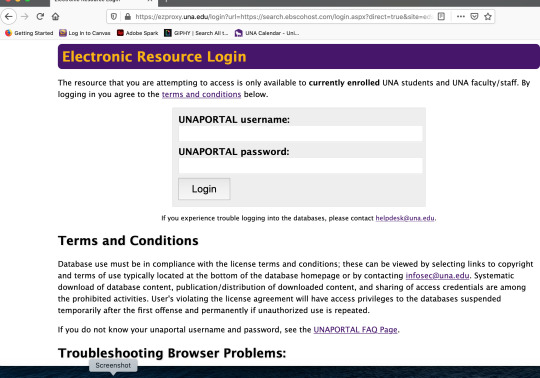

If you are using a computer in a UNA computer lab (maybe also if you are connected to campus wifi; I’m not sure about that one because it’s been a long time since I tried that), you will get your search results immediately. OTHERWISE, clicking “search” will take you to a page that asks you to log in to prove that you are a student.

Step Three:

Use the same username and password you use for Canvas.

#ProTip here: Don’t include the “@una.edu” after your username; that will confuse the system and you’ll get an error message. So my username for the library website is “sgsmith” not “[email protected]” - I may be the ONLY person who finds this confusing, but for some reason about half the time I type the whole thing and only remember this is a problem when I get an error message. DON’T MAKE MY MISTAKES, okay??

Once you’re all logged in, you get your search results. That page will look something like this:

There are plenty of things you can do just from this first results page, BUT the purpose of today’s module is to get you to the “next level,” and in particular to get you familiar with the quick’n’easy process for filtering your search results to “peer-reviewed” journal articles (because your research essay guidelines call for at least five of those).

So . . .

Step Four:

0 notes

Text

Library Research Tips & Tricks: Part 2/?

Part One

Once you click the link to the Collier Library website, you’ll see that there is a search box right up front on the landing page. So:

Step Two: Enter any search term related to your topic (see my tips in the infographic below).

^ yes, I like using Marvel examples. One semester I used only examples from Star Wars and in evaluations somebody wrote that “she taught us to Star Wars,” which I am still trying to figure out. Fortunately my boss is a big SW fan and was very impressed.

0 notes

Text

Library Research Tips & Tricks: Part 1/?

First up, you’ll probably want to review the research essay guidelines and/or print them out to keep handy as you conduct your research. There is also a checklist, but that’s going to be more useful to you later in the drafting stages.

In the meantime, I want your FIRST module on library research to focus on how to find peer-reviewed sources, because this seems to be the part that trips students up the most often.

The good news is that once you get the steps down pat, this part suddenly becomes really easy and you can devote your attention to other aspects of your research process.

So here we go - I’m breaking this WAY down, one step at a time. Okay?

Okay.

Step One: Start at www.una.edu and click the link near the top of the page to go to the library website.

0 notes

Photo

Link to Part One

If you choose Option A, I have provided posted a screenshot of last Friday’s prompts for you (just above) as a reminder.

If you choose Option B, you may need a little more guidance getting started, so here is how I would break that down:

Consider your research topic and identify an area for development in which you either

a) describe a possible course of action and argue, using the best evidence available, what its likely outcome(s) would be

OR

b) describe some aspect of the situation you are researching and argue, using the best evidence available, what were the main and contributory factors that led to that situation

In essence, these are pre-sushi (”What If?”) and post-sushi (”how’d we get into this???????”) approaches to your potential research topic.

It doesn’t matter to me which one you pick; if you are having trouble settling on a research topic, Option B may help you decide. On the other hand, if you are putting all your energy into figuring out your research topic, then building an essay from the beginning you made on Friday might save you some stress. Either way is fine.

Whatever you decide, you should draft your essay with enough time left over to follow the same basic steps to revision I gave you as we worked on the definition essays. Then, upload the final version of your cause & effect essay to Canvas as a PDF by 11:59pm on Friday.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Basics: Start by reviewing the basic “this is what a cause & effect argument looks like” info I posted for you on Friday.

From there, you have a couple of options, so on to the next post ...

1 note

·

View note